This paper explores the impacts of the fast spatial expansion of Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia, on the suburb small-scale farming community. Recently, combined with rapid population growth and booming economy, the city experienced a rapid physical expansion without proper urban planning. The sprawl of the city has dislocated small-scale farming communities in the suburbs and led to one of the major deadly popular protests against land dispossession in the modern history of the country. The physical expansion to surrounding farmlands has threatened the socio-economic life of farming communities surrounding the city through dislocation, resource dispositioning, and why the situation has received ethnic dimension. This study highlights that in addition to the natural urban growth, corruption in the government and the use of land for political leverages have played a significant role in the forced eviction of peasants.

The recent large-scale foreign control of land in the sub-Saharan Africa countries including Ethiopia has concerned scholars, who worry that land grabs could result in a massive displacement of African smallholders (Baxter, 2010). Many scholars assume that land grabs are part of the larger neoliberal move towards economic globalization as well as mechanisms of land control (Peluso and Lund, 2011), and as such, there is a strong link between land grabs, primitive accumulation, and accumulation by dispossession (Adnan, 2013). However, the current focus of academic interest in land grabbing has mostly concentrated on large-scale land deals in developing countries through the direct involvement of foreign investors. Zoomers (2010, 429) argues that most forms of land control involve large-scale cross-border land deals or transactions that are carried out by transnational corporations or initiated by foreign governments. This approach undermines the role of the governments of developing countries themselves, as well as the domestic political economy, in shaping land controls and agrarian relations (Benjaminsen and Bryceson, 2012; Lavers, 2012). However, either way, the seizures of land, whether for development or conservation, have inflicted overwhelming social and environmental hardships (Vigil, 2018), leading to the transformation of agrarian environments through urbanization and depeasantization. More specifically, the process is leading to a global pattern of depeasantization and the proletarianization of dispossessed peasants in developing economies (Lavers, 2012; McMichael, 2010).

One of the new frontlines of land grabbing in developing countries is an urban expansion (Peluso and Lund, 2011). Africa remains the least urbanized continent, but the continent is currently experiencing the fastest urban growth rate in the world (Brückner, 2012). In Ethiopia, approximately 21% of the population live in urban areas, but the rate of urbanization is expected to accelerate at an annual rate of about 5% (Ozlu et al., 2015). Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capital and the diplomatic center of Africa, is one of the fastest-growing cities on the continent, with an estimated total population of four million, accounting for approximately 30% of Ethiopia’s urban population (Spaliviero and Cheru, 2017). The city, which was established in the 1880s by Emperor Menilek (r.1889-1913) in area predominately settled by the Oromo and swiftly grew to become the political and economic capital of Ethiopia (Dibaba, 2018).

Since its establishment, Addis Ababa (Figure 1) has been growing spacially displacing the surrounding peasants (Chala, 2015). The uncontrolled expansion of Addis Ababa and the eviction of the peasants from the city’s peripheries is related to the center-periphery power relationship that has developed in the country over the last 150 years as well as more recent developments in the contemporary global political economy (Degefa, 2019; Wayessa, 2019). This paper explores the impact of the spatial expansion of Addis Ababa on the small-scale farming community around the city. More specifically, it examines how the physical expansion of Addis Ababa is threatening the socio-economic life of the surrounding farming community through land and resource dispositioning. It further examines how government agents have been using land around the city for political leverage and means to silence political dissents.

In Ethiopia, peasants are dispossessed by unplanned urban expansion, the development of agro-industries, and the modernization of the rural economy. The land dispossession of peasants needs to be better understood. In keeping with this, in the following, the state’s commodification of land, the dispossession of smallholders because of urban expansion and modernization, and the peasants’ reaction against dispossession and its consequences were discussed.

The commodification of land and dispossession of smallholders

The present spatial expansion of the Addis Ababa is affecting the livelihood of small-scale farmers by displacing them from their farmlands and polluting the surrounding environment through uncontrolled waste disposal at the city’s edges. Using the development agenda as a strategy of acquiring land from its traditional owners, the government commoditized land. Besides, the government reported controlling homeland and diaspora based opposing individuals through offering special benefits including grating land to silence them. Some dispossessed citizens have stated that they were forced from their ancestral land, and some of the displaced family members became homeless in the city since they do not have enough income or job security to rent.

Although land is a mere commodity for government agents and the fortune seekers, the dispossessed people see land not just as a resource and use the phrase lafi keenya lafee keenya (literally translated as “our land is our bone”), in which the bone metaphorically represents a lineage. Thus, passing land on from generation to generation represents the continuity of lineage, while land deprivation means the disruption of this lineage. The displacement of smallholders disrupts the traditional social life of the peasants as well as their livelihoods. During the 2010 national election TV Debate, a member of one of the opposition parties expressed his party’s concern about corruption and the large-scale forced displacement witnessed across the country, especially around Addis Ababa:

“… as indicated in the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia [FDRE] constitution and the ruling party policy document, land is public and remains the property of the state. However, is land public property now? Or is it state property? Can it be the property of both? In our opinion, land is no longer the property of the people or the state. Land has become the private property of the ruling party leaders, who sell it as they like, give it to their associates, distribute it freely among their families and their friends. Land is a way of recruiting party members; land represents blackmailing even educated people to stop them from speaking out for justice. For political purposes, land has become a magnet to attract diaspora […] while ordinary citizens have no plot on which to build the most basic shelter. For a few people, land has become a short cut to accumulating wealth rapidly […]. We know that land is this country’s most important asset. Based on the link between people and their assets, it seems that Ethiopia is now divided into four classes. The first class are those who give away land [rent-seeking higher state officials], the second class are those who are awarded land by the authorities [lower officials, new party recruits and the relatives of officials], the third class represents those who sit back and watch while these transfers occur, and the fourth class are the peasants who are victims of the forcible displacement and dispossession” (ETV, 2010).

In a related TV interview, former State Minister of Ministry of Communication Affairs of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia stated that:

“…in my opinion, more than 55% of the displaced and dispossessed people are Oromo peasants. For the construction of real estate projects alone, around 4.8 to 5.2 million km2 of land have been snatched from the peasants. This ruined the lives of 29 rural kebele [a rural municipality], each with an average of 1000 households, meaning an estimated 150,000 people” (ESAT, 2014).

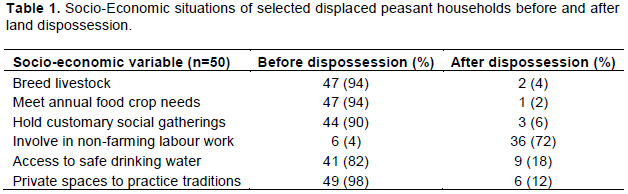

One woman stated that after her family became a victim of displacement, her husband had become a security guard in one of the commercial buildings built on the site of their former rural village, while her two adult sons were daily laborers with no job security and low pay. Another interviewee reported that the forcibly displaced peasants who used to sell their own surplus grain to give themselves an income are now relying on the markets to buy food. The peasants have been deprived of their customary land rights and livelihoods, and have been transformed from interdependent producers to daily laborers (Table 1).

Moreover, due to the disruption of communities, their chidden lost the opportunity to learn in their language and practice their traditions. Participants reported that they were told when the government acquired their lands for development that each family member over eighteen years of age would be given 250 km2 on which to build a house now or in the future. However, later reports revealed that most unmarried adult men and women in households were not given what they were promised. Accordingly, of the total of eleven unmarried adult men and women, only four of them were given sites. They were not also given the chance to register for newly built condominium housing since they were rural and had no urban identification cards required for the registration.

The integrated master plan

The adoption of Addis Ababa’s new master plan is part of a national move towards economic transformation. This master plan, the Integrated Master Plan for Addis Ababa and Surrounding Oromia Special Zone, is looking to incorporate Oromo cities within a radius of roughly 100 km from Addis Ababa engulfing any Oromo rural communities within that area.

Oromo activists reported that the land dispossession plan was not only targeting smallholders and peasants around the city, but the whole of Oromia regional state. The state risks being split into western and southeastern areas, possibly restricting free interaction between the farming communities in the two areas and weakening the unity of the people. Activists claim that successive Ethiopian regimes have weakened the Oromo people by dividing them along regional lines to weaken Oromo ethnicity. According to them, the Integrated Master Plan, therefore, is a system of government planning with short and long-term economic and political objectives.

As part of its new master plan, the Ethiopian government promises to provide an enhanced waste collection and waste treatment system for the city, enlarged green area coverage in the inner city and the establishment of affordable and standard housing by constructing residential buildings mainly in new rural areas incorporated into the city under the master plan. However, the plan has not considered the fate of smallholders around the city, and as a result, the strategy to modernize and expand Addis Ababa comes at the expense of smallholder communities who are forced out and given little chance to integrate into urban life.

With the agenda of improving infrastructure, increasing green spaces in the inner city, and modernization, the city administration has demolished many poor neighborhoods. It has been widely observed throughout the city that the demolished poor neighborhood sites have been replaced by industrial areas where national and international corporations have established large-scale business enterprises. For most of the displaced households, new affordable residential apartment buildings (condominiums) were constructed mainly at the city’s outskirts in areas from which smallholders were displaced. This has involved massive real estate construction as well as the establishment of industrial parks. The displaced peasants have not been given affordable houses because the urban policy processes excluded them from the development program, failing to give them compensation for the lands, although the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (restructured as the Prosperity Party in 2019) policy document underscores the importance of linking urban and rural areas to support rural development. The dispossessed peasants consulted reported that they regularly face harassment from government agents and developers if they are found pasturing cows and collecting firewood even in land enclosures that have yet to be developed. In interviews held with a community of the displaced peasants, the participants stated their concerns as follows:

“We lost the land we inherited from our mothers and fathers. The government officials forced us to sign an agreement of eviction to give up our land for condominium constructions with a compensation payment of 18.50 ETB (0.60 USD) per square meter. Now we have nothing and some of our community members are forced to become security guards while others are daily labourers in construction companies with no enough pay or job security. The payment is as low as 50 ETB (1.7 USD) per day.

Sewerage from the new residential buildings and the city has polluted the stream we used to use for drinking and for our livestock […] We are refused access to the clean water supplied by the city for the residents of the condominiums […] We are forced to travel for two hours to find an unpolluted stream for drinking water and for our livestock […] When we try to appeal our case to the government, local officials bribe our few educated coordinators and we cannot move forward with the legal case” (OMN, 2018).

In a similar interview, a dispossessed and disheartened husband and wife shared their experience and told me how their lives had changed following the dispossession of their land as well as the tricks and empty promises involved during their displacement in the interviews with the ruling party owned radio station known as Fana Broadcasting Corporate S.C:

“We used to cultivate teff, wheat, peas, and other crops. I used to harvest around thirty quintals per year. We used to live a happy life […]. We had enough food grains […] we used to buy only salt and food oil. Seven years ago, peasant households living around here were called and told to give our land to the government as it was needed for investment. We asked what would happen to use, and they told us they would give us land, supply clean water, build clinics, and electricity supplies. Then they gave us 18.50 Birr ($0.60) per square meter for cultivable land and 9 Birr ($0.30) per square meter for the pastureland. We did not know about handling cash and now we have no money and no land […] I am an old man and to keep my family alive, I work as a labourer in construction…” (FBC, 2018).

The dispossession of peasant land is also embedded in the arts and music of the cultural group with which the peasants are linked. The agony and resentment of the displacement of peasants around the city or incorporated into Oromo arts as evidenced by artists’ lyrics. One of several songs composed goes as follows:

In the past mother feeds her offspring,

Now she tied up her waist within their waistbands;

What was left for the future is gone.

Oh, my homestead, for my children you are hell, for others you are paradise.

When I look down on Finfinnee [Addis Ababa] from Mount Entoto,

I see lines of high-rises; there is no hut for me there.

Oh, my homestead, what did I do?

Tell me if you have heard anything.

Speak, my homestead, where my umbilical cord lies buried.

Tell me how can I sleep when I have been robbed by others?

The land is in my bones

Who can abandon their bones?

The lyrics of these songs metaphorically blame the land, which is welcoming others at the expense of the people who claim its customary ownership. It is common practice for Ethiopian peasants to use metaphors to express their disappointment in their dispossession at the hands of a repressive regime. The peasants were dispossessed through coercion and broken promises, and the government leased some of land to private investors while keeping the rest to develop with the help of international financial institutions.

Although protests forced the Ethiopian government to scrap the master plan for the new city the people who were displaced are still suffering the consequences. This is because land continued to represent a means of accumulating wealth and making new friends among political leaders. More importantly, the scrapping of the master plan and the associated political situation offered government officials more opportunities to engage in land-related political power abuse and corruption, as there are no effective regulations in place to monitor land-related activities. Meanwhile, the compensation peasants given were significantly lower in comparison to land values in Addis Ababa, where the lowest lease value in 2016 was over 200 ETB ($6.70) per square meter. Moreover, most of the displaced peasants were illiterate and had no idea how to handle cash, and no advice was offered to them. The individuals interviewed stated that money was nothing compared to land. They expressed resentment when the reflected on how they had lost the land they had inherited from their families and were planning to pass on to their children. One of the displaced elders told me that their rural village had been destroyed, their families dispersed and their social fabric has broken.

Ethnic Oromo peasant resistance

The peasants have never been irresponsive about their alienation, although the government has implemented its policies under legal cover. The resentment of peasants around Addis Ababa reached its climax with the announcement of a new master plan that sent shockwaves to the Oromo communities living in different parts of the country in the State of Oromia as well as Oromo communities in the diaspora. The protests were rooted in the long history of modernization policies in Ethiopia that marginalized Oromo peasants. According to the people interviewed, the Oromo have historically been marginalized in Addis Ababa and lack economic and cultural representation, which means that this resentment has accumulated over time. The Oromo stated that while the city has offered them few socio-economic gains, its sprawl has destroyed their livelihood through displacement and the pollution of the local environment through deforestation associated with new construction and the unregulated disposal of the city’s waste into surrounding rural village land. The resistance against the master plan or the “Master Killer,” as it is colloquially referred to by the protestors, has claimed over 140 lives. The people we interviewed stated that instead of solving preexisting problems related to the unchecked spatial expansion of Addis Ababa, the master plan succeeded in little more than allowing legalized eviction, affecting the livelihood of small-scale farmers by displacing them from their farmlands. Following the deadly protests, the master plan was shelved. In one forum held regarding the master plan, the ruling party official who is now the mayor of Addis Ababa claimed on state-owned Television broadcaster:

“The issue of Addis Ababa and the surrounding cities is not an urban issue; it is a question of identity. When we say identity, we mean the plan should respect and incorporate Oromo identity, history and politics […] We already know about the expansion of Addis Ababa […] What we want is not an Addis Ababa that grows by evicting Oromo peasants, but one that embraces the peasants and their children” (OTV, 2014).

Shelving of the Master Plan, however, did not stop the continuing conflict over the land around the city. The government fell back on the concept of public ownership of land, which legalized the dispossession of peasants because it was the government authorities themselves that carried out much of the illegal appropriation of land. In other words, regardless of the claim, eviction and tricking the peasants to concede their land with poor compensations from the peasants is going on as usual under his leadership.

The Oromia Regional State, which governs the rural villages around Addis Ababa, superficially opposed the plan, but the covert complicity of some Oromo regional officials in the illegal land deals extended to an attempt to legitimize their ownership of the land they had amassed from dispossessing the peasants. When the resistance ignited by the master plan took a more radical dimension, the Federal Government of Ethiopia reshuffled its leadership, bringing what appeared to be more progressive leaders to power in 2018, at which point some democratic political reforms were introduced, allowing conflict-generated diasporas and exiled political parties to return to the country. The new leaders who had been vocal in criticizing the dispossession of poor peasants now sat back and made little effort to reverse the displacement. Instead, efforts are now being made to formalize the land seizures, which implies that the dispossession of peasant land is being accepted as a means of modernization and development. The reality is that the wealthier and more powerful elites are now becoming wealthier and more powerful by depriving the masses of the most important asset, forcing the once self-sufficient producers to sell their labour to the group that dispossessed them. More importantly, the use of land as a means of appeasing activists and individuals with different political views from the government continues even under the so-called the new reformist leaders, who are disabling coordinated resistance against land alienation of smallholders.

The growth and expansion of Addis Ababa have brought disputes and disagreement, and there are two contesting views on the current size and the development of the city. The first attributes the current state of the city to its central geographic location and booming economy, which attracts hundreds of thousands of people from all corners of the country (World Bank Group, 2015). The city’s rapid population growth led to congestion in the inner city, limiting green spaces and affecting the poor neighborhoods particularly badly, meaning that the city has expanded to take in surrounding rural areas (Spaliviero and Cheru, 2017: 2). Addis Ababa’s current expansion to the periphery is presented as being driven by a lack of space in the center and an effort to modernize the city.

The second view, mainly supported by Oromo nationalists, attributes the current unchecked spatial expansion of the city to Ethiopia’s modernization policy that deliberately targets smallholders. This view views the expansion as a politically motivated land grab. Major development projects in the country have targeted smallholders whose land-use strategy is considered inefficient in terms of contributing to Ethiopia’s economic transformation. Supporters of this viewpoint see the modernization of Addis Ababa through expansion into the surrounding rural villages while increasing green spaces in the inner city as part of the ongoing displacement and dispossession of smallholders who have few socio-economic opportunities, leaving them economically marginalized and politically unrepresented. Oromo nationalists claim that historically the city has failed to absorb the displaced smallholders and that the displacement and the Oromo’s political and economic marginalization and ethnic othering shows that the government of Ethiopia still only reflects the identities of the northern elite, meaning that feelings of ethnic otherness are becoming normalized.

Quinn and Halfacre (2014) examined the social, emotional, and cultural attachments of peasants to the land they used to cultivate beyond its use as the base of their subsistence. Terminski (2014: 13) states that the displacement of people from their land in the name of development not only deprives them of their sustenance but also destroys the cultural, spiritual, and emotional fabric of their lives, which are strongly linked to the land. The benefits of the dispossession are kept in the hands of the already wealthy elites. Baird (2011: 11) stresses that the neoliberal perception, which is that peasants are “making unproductive use of resources and are resistant to integration into the market economy” motivated the large-scale land concessions and the removal of peasants. This same perception is documented elsewhere in Ethiopia, where the indigenous people of the Omo valley are dispossessed land by the government because the land was “idle” or underutilized and would be better used contributing to national development plans, although peasant farmers had been using the land for cultivation and grazing (Daniel and Mittal, 2010: 19). As seen in Addis Ababa and elsewhere in Ethiopia, subaltern communities who are victims of the projects are rarely embraced in the development program. For instance, although Addis Ababa is located in the Oromia State, ethnic Oromo smallholders comprised the majority of the inhabitants surrounding the city, and the Oromo are the largest ethnic group in Ethiopia, within the city only around 20% of the city’s total population is Oromo. Thus, it appears that while the city is expanding into the Oromo farmlands, it is not absorbing the displaced Oromo peasants or assimilating the people into the dominant urban cultural group since they do not have private space to practice and maintain their cultural traditions in the urban setting. The suppression of the ethnic identity by the city’s social structure led to the underrepresentation of Oromo in the city.

Ethiopia’s ambition of rapid economic development and transformation has led the country to “pursue the strategy of fostering the governance and management of rapid urbanization to accelerate economic growth” (Spaliviero and Cheru, 2017: iii). According to the World Bank (2014), Ethiopia’s government has also focused on improving urban infrastructure by building more resilient and greener cities in the country. In 2015, during the first Growth and Transformation Plan (GTP), Addis Ababa received a new master plan that set out to expand the city into the surrounding rural areas, involving a massive dislocation of the neighboring agricultural community. According to the World Bank (2014), the adoption of Addis Ababa’s new master plan is part of the nation’s move towards economic transformation, a move that involves standardizing housing by constructing new residential buildings mainly in formerly rural areas that have been incorporated into the city by the new master plan (Spaliviero and Cheru, 2017: 49). The displaced peasants have not been given affordable houses because the urban policy processes excluded them from the development program, failing to give them compensation for the lands even though the FDRE policy document underscores the importance of linking urban and rural areas to support rural development. As a result,the new economic transformation, like its predecessors, has failed to embrace the historically marginalized smallholders around the city.

Studies associate the present-day dispossession of peasants, especially in the Global South, with the continuity of primitive accumulation of capital or accumulation by dispossession (Baird, 2011; Harvey, 2003; Perelman, 2007; Terminski, 2014; Webber, 2008). According to Harvey (2003: 145), “displacement of peasant populations and the formation of a landless proletariat has accelerated” in several countries over the last fifty years. This aligns with Baird’s (2011: 11) work in Laos, where he observed: “…the concept of primitive accumulation is useful for understanding how the development of large-scale economic land concessions are impacting on rural peoples.” Baird (2011: 11) also identified how many farmers are “rapidly being propelled into wage-labour markets in ways that cannot be considered voluntary”. It was argued that the current state of dispossession of smallholders around Addis Ababa for development projects through the involvement of local and international financial institutions is part of the ongoing process of primitive accumulation. Although the displaced peasants were not directly coerced into joining the labor market, people whose livelihoods were based on the land are now being forced to join the labor market to ensure their survival. However, limited opportunities in the labor market mean they are forced to work at extremely low pay rates with no security. Meanwhile, investors benefit directly from the dispossession of the peasants and are now treating the peasant laborers unfairly.

The dispossessed peasants in villages around Addis Ababa were promised a clean water supply, health services, and other social provisions. In principle, this is the core of Ethiopia’s urban policy, which seeks to develop urban areas while improving the living standards of the surrounding rural villages (AACPPO, 2017). The reality is, however, that their own government tricked the peasants and promised services, which they could not provide. While displaced peasant families need to travel for two hours to collect water from streams, tap water put in place by the city is available within less than 50 m, but not to the peasants. This situation aligns with Bassett’s (1988) claim that urbanization brings better health services and affordable housing opportunities only to the politically and economically dominant group, and has a profound negative effect on the way of life of economically and politically weak suburban small-scale farmers. Adnan’s (2012) case study in Bangladesh shows that “the neoliberal policy of privatizing state lands provided” government officials with “the kind of legal cover” that they needed to “legitimise illegal possessions” of land for their personal benefit. Similarly, it appears that the Addis Ababa’s new master plan has been set out to legalize lands illegally taken from peasants by government agents and their allies. Moreover, although the new Master Plan was compromised since government officials had already appropriated land illegally, there are efforts to put legal jurisdiction of Addis Ababa into place to safeguard interests of the corrupt officials, who will gain more allies through land allocations.