The study on access to food when it is available and affordable is to increase knowledge of the extent the right to food is recognized and protected as a human right in South Sudan. The objective of the research is to determine the level of state’s obligation in protecting the right to food and the level of food availability. Secondary data is reviewed in contrast to where a questionnaire field survey is carried out. The results show that South Sudan is among the most food insecure countries with as high as 33% of the population depending on food aid for nutrition. At least 1 million people are severely food insecure. In addition, investment in the agricultural sector is limited with budgetary allocation to the sector as low as 0.1% of the total budget. South Sudan has limited legal obligation to recognize and protect the right to food because it is not explicitly stipulated in the Transitional Constitution, 2011 and neither in any other legal instrument. However, South Sudan is a party to the Convention on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 1966, which confirms that the States Parties recognize the right of everyone to adequate food and the fundamental right to be free from hunger. In contrast, in developed countries such as the United Kingdom those with limited means are entitled to social security benefits which include income support so that people have access to food.

South Sudan is a landlocked country endowed with abundant and diversified resources in Sub-Saharan Africa. It has a population estimated at 8,260,490 and an area of 644,330 km with 83% of the population living in rural areas (Southern Sudan Counts, 2010). Most people in the rural areas are subsistent farmers.

South Sudan has a high potential for increases in agricultural production to achieve food security. The National Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security is charged with making South Sudan fully food secure at household and regional level and, to produce quality surplus products for the market (Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, 2006). Focusing on the extent to which the state is executing its obligation, if any, to recognize, respect, protect and promote the right to food, is imperative for sustainable development goals at the national level. This is intended to increase knowledge of the right to food and food security in South Sudan. Apparently there has been hardly any study carried out to determine to what extent South Sudan is legally obliged to recognize, respect, protect and promote the right to food and food security as a human right.

The purpose of the research is to examine causes of food insecurity, assess the extent the state is recognizing, respecting, protecting and promoting the right to food, and to assess availability, adequacy and affordability of food.

The problem is that it is not clear whether South Sudan has an obligation to recognize, respect, protect and promote access to food as a human right. This is because South Sudan is a party to the Convent ion on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 1966, which confirms in Article 1(1, 2) that the States Parties recognize the right of everyone to an adequate standard of living for himself and his family, including adequate food and also that the States Parties recognize the fundamental right of everyone to be free from hunger. This makes the focus on assessing the extent to which South Sudan has an obligation to protect the right of access to food for nutrition as a human right. This is because lack of food for nutrition is a problem. For example, in 2016 the number of undernourished people in the world increased to an estimated 815 million, up from 777 million in 2015 and the food security situation has worsened in parts of Sub-Saharan Africa including South Sudan (FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, and WHO, 2017). In view of the aforementioned food security situation, an assessment will be made of the extent people in South Sudan have access to food as a human right.

With regard to Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), South Sudan is committed to eradicate extreme poverty and to that end has envisaged that the proportion of the population that would be living under the national poverty line by the year 2013 would have gone down by 46% (National Bureau of Statistics, 2013). However, undernourishment of people remains a big challenge. This is evidently so when the budget for agriculture and food security is a mere 0.1% of the total budget (Ministry of Finance and Planning, 2017). This seems to suggest that there is hardly any investment in agriculture to improve production for the achievement of food security.

The research methodology used is secondary sources review for qualitative data in contrast to quantitative methodology where a questionnaire is administered to a sample got from a sample frame.

The right to food at global level

The right to food means there should be an obligation to protect the right for people to have access to food for nutrition and also guaranteed availability of food at all times as needed. Worldwide, there are more than 700 million people suffering acute undernourishment and in South Asia there is the greatest concentration of people suffering from hunger, and it is in Africa that their situation is deteriorating fastest (Delpeuch, 1994). Undernourishment through lack of food and malnutrition through a qualitative lack of proteins, vitamins or minerals, are common, especially in the period between harvests when food stocks are virtually exhausted. The concern is how to ensure food security.

Considering nutritional well-being to be a basic right of every individual means that in principle, no compromise is acceptable concerning the right to food (FAO, 1996a). The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) in 1966 defined and formalized the right to food as a basic human right. Article 11 of the Covenant stipulates that the States Parties to the present Covenant recognize the right of everyone to adequate standard of living for himself and his family, including adequate food, clothing and housing, and to the continuous improvement of living conditions. Also, Article 11 stipulates that the States Parties to the present Covenant, recognizing the fundamental right of everyone to be free from hunger, shall take individually and though international cooperation, the measures, including specific programmes, which are needed to improve methods of production, conservation and distribution of food by making full use of technical and scientific knowledge, by disseminating knowledge of the principles of nutrition and by developing or reforming agrarian systems in such a way as to achieve the most efficient development and utilization of natural resources.

In the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), 1948 Article 25 stipulates that everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond their control.

Under the UDHR and in the ICESCR, the right to food at the global level shows that this right is recognized and promoted in whatsoever circumstances. The right to food is a human right that cannot be ignored or wished away. It is a fundamental human right that is seen as equivalent to the right to life, liberty and the security of person. This may explain the extent the right to adequate food is recognized in several instruments under international law. It is reaffirmed that the right to adequate food is indivisibility linked to the inherent dignity of the human person and is indispensable for the fulfillment of other human rights enshrined in the International Bill of Human Rights.

The realization of the right to adequate food is one thing. However, it has been noted that while reporting guidelines are available relating to the right to adequate food, only few states parties have provided information sufficient and precise enough to enable the determination and prevailing situation in the countries concerned with respect to the right to food and to identify the obstacles in the realization of this right. This suggests that it may not be possible to assess precisely the extent to which the right to adequate food is being realized in the various countries. Nevertheless, the strong expression on the right to food at the global level shows the world’s determination on the inherent human right of everyone to food for nutrition and well-being. It is for everyone not to be seen going hungry to bed.

The right to food at the global level brings food security into focus. When the Heads of State and Government gathered at the World Food Summit in Rome in 1996, they declared that, food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life (FAO, 1996b). The declaration by the Heads of State and Government has been quoted from time to time that is has become the definition of food security. This means that according to the right to food at global level, all people; at all times anywhere have the right to adequate food for nutrition and well-being. As agriculture is at the heart of food security (Maxwell, 2001), this means investment in the agricultural sector for increases in production to achieve food security is the key. Since the agricultural revolution the vast majority of people have lived on little but grain (Wynne-Tyson, 1988).

Investment in improved seeds, fertilizers, water pumps, better animal drawn ploughs and harrows, and simple revolving weeders and threshers works to improve yields for the achievement of food security (Lappe and Collins, 1982). According to Lappe and Collins, the faster growing seeds of the green revolution make it possible for two and sometimes more crops to be grown successfully in the same field in one year. This goes to confirm that investment in improved technology is the key to increase production for food security. Without food availability, it may be unrealistic to expect the right of food and food security to be realized. However, the availability of food does not necessarily mean that everyone will have automatic access to food. Access to food implies somebody must have the means to purchase food in the market. This means that somebody needs to have an income in order to have access to food that is needed by purchasing it. This is where it is imperative to determine the extent the state is obliged to protect the right to food as a human right in a situation where anybody has no income.

The right to food in South Sudan

In South Sudan, the right to food is not mentioned in the Bill of Rights in the Transitional Constitution (Ministry of Justice, 2011). However, the right to food is implied. Under Economic Objectives, Article 37(1) states that the principal objectives of the economic development strategy shall be the eradication of poverty, attainment of the Millennium Development Goals, guaranteeing the equitable distribution of wealth, redressing imbalances of income and achieving a decent standard of life for the people of South Sudan. The right to food is therefore underpinned by the economic objectives. For example, the objective on eradication of poverty implies people will have access to food.

Causes of food insecurity

Causes of food insecurity are many. They range from man-made to natural calamities. Food insecurity is either transitory or chronic or both. Both transitory and chronic problems of food insecurity can be severe. Transitory food insecurity is seasonal while chronic food insecurity occurs over a long period of time. Table 1 shows a classification of food insecure households, an example from Ethiopia (Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, 1996).

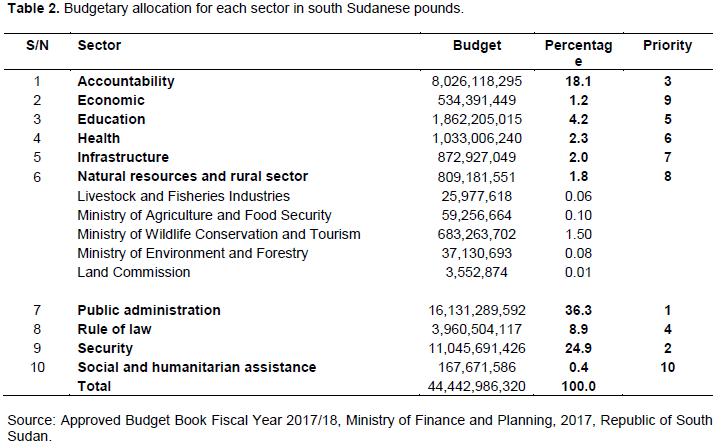

In South Sudan, more than a third of the population of 8.26 million is severely food insecure and South Sudan is one of the most food insecure countries (United Nations, 2016). Table 2 shows budgetary allocation for each sector in South Sudan.

Table 2 above shows another cause of food insecurity where the agricultural sector is being starved of resources more than any other sector. The causes of food insecurity can be traced to the poor budgetary allocation to the agricultural sector. Table 2 confirms that the agricultural sector gets 0.1% of the total budget, totally far below what the heads of African government had suggested decades earlier that the budget for agriculture should be up to 25% of the total budget (Maxwell, 2001). This was clearly to achieve food security on the continent as there should be a deliberate strategy to improve food security (Hubbard, 1995).

In South Sudan, conflict and insecurity have pushed the country down into the situation of severe food insecurity. A major military confrontation between the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) factions erupted in mid-December 2013 and the conflict is still on-going and having major impacts on food security status of South Sudanese households (FAO/WFP, 2014). According to FAO/WFP, inter-communal and inter-ethnic conflicts during 2013 and high food prices have caused enormous impacts on food security of households. This confirms that conflict and high food prices are some of the main causes of food insecurity in South Sudan. In a survey in May 2013 on the biggest issue or concern that most impacts people’s daily life or family, the vast majority of respondents said the biggest issue or concern was food shortages/famine (International Republican Institute, 2013). This seems to confirm that the achievement of food security should be one of the top priorities in agricultural policy. This means the causes of food insecurity should be dealt with accordingly. As stated by Hubbard (1995), there should be a deliberate strategy to improve food security. The eruption of conflict in Juba, the capital, on 15 December 2013 spread rapidly to Jonglei, Unit and Upper Nile states has led to gross human rights violations with farmers fleeing to escape the conflict (South Sudan Human Rights Commission, 2014) is clearly making food security worse. Sub-Saharan Africa is the only region in the world currently facing widespread chronic food insecurity (Devereux and Maxwell, 2001).

Assessment of the extent the right to food is a human right

At the global level the right to food is recognized as a basic human right. The fundamental right of everyone to be free from hunger is recognized and measures are to be taken to improve methods of production and distribution of food. Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the wellbeing of people and this includes the availability of food. However, assessing precisely the extent to which the right to food is a human right is a challenge because of the lack of sufficient information. The right to food as a human right is mostly in theory. In practice, it is hardly possible to assess the extent to which the right to food is a human right.

In South Sudan it is not possible to assess the right to food as a human right. There is no legal instrument to oblige the state to recognize, respect, protect and promote the right to food as a human right. It is therefore not possible to make any assessment when there are no legal instruments. However, through the United Nations the right to food is recognized when people are severely food insecure. This usually prompts an appeal for humanitarian assistance for people to have the right to food for nutrition in protecting the right to life.

Assessment of food availability, adequacy and affordability

Agricultural yields in South Sudan remain low due to limited irrigation, scant use of certified seeds and fertilizers, limited use of modern technology and small plots of land (WFP, 2012). This suggests that availability of food is limited. According to the WFP stagnation in agricultural growth coupled with a significant increase in the population has led to cereal deficit. A total of 4.8 million people, that is one in every three people in South Sudan, are food insecure and food insecurity is further aggravated by seasonal variations and worsening food production conditions (United Nations, 2016). This seems to suggest clearly that availability and adequacy of food is limited in South Sudan. However, even if food is available and adequate, this does not guarantee that everyone can afford to access it. For example, Western Equatoria in South Sudan produces surplus of maize and sorghum, but yet hunger still affects 23% of the population (WFP, 2012). The WFP states that to ensure food security the ability of households to buy sufficient food needs to be supported by increasing incomes and purchasing power.

It can be assessed that food availability, adequacy and affordability in South Sudan is a challenge. South Sudan has been gripped by soaring prices in the markets and shortages of essential commodities (Taban, 2015). It can therefore be seen that food availability and adequacy may be a challenge but food affordability is an acute problem in South Sudan.

Food security is not just a question of raising food production for availability and adequacy, but ensuring that the rural and urban poor do not go hungry (World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987). To ensure that the rural and urban poor do not go hungry suggests that the poor must have the means to have access to food. This means the poor must have some income most likely through employment. However, when someone is unemployed and lacks any means of income, access to food may be a challenge. In rich developed countries of the world such as the United Kingdom, the unemployed are likely to be entitled to social security benefits which include income support (Le Grand, 1982). It is clear that in the United Kingdom, a rich country, the unemployed have income support that enables them to have access to food. In contrast, in South Sudan, a poor country, there is no such thing as social security with income support to the unemployed as one of the benefits. This makes it obvious that the poor unemployed in developing countries face much more food insecurity than those in rich developed countries.

The mission of the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (2006) in South Sudan is to transform agriculture from traditional system to a modern one to achieve food self-reliance by 2011. However, the results of the research show that:

1. Based on the estimates from the October 2011 Food Security Monitoring System (FSMS) at least 1 million people in South Sudan are severely food insecure and this category would require unconditional humanitarian food assistance (WFP, 2012).

2. Decades of war and conflict have left South Sudan food insecure and dependent on food imports (Multi Annual Strategic Plan, 2012).

3. It is estimated that 33% of the population of South Sudan is severely food insecure countries (United Nations, 2016).

4. The budget for the agricultural sector is incredibly as low as 0.1% of the total budget for the fiscal year 2017/18 (Ministry of Finance and Planning, 2017).

The results of the research show that South Sudan will continue to be food insecure until agriculture is accorded the priority it deserves as the backbone of the economy and peace is achieved in the country. Achievement of peace and a stable environment, and investment in agriculture are the ways forward. The focus on the right to food should also be on self-reliance in food production. The real criterion of self-reliance must always be that all the people have access to an adequate amount of food which requires the allocation of control over agricultural resources at the local level (Lappe and Collins, 1982). Lappe and Collins see self-reliance as depending on the initiative of the people, not on government directives.

There are two ways to invest in agriculture. Budgetary allocation to the agricultural sector should be increased as one way and attraction of both foreign and domestic investment is the other. These are the ways to development of the agricultural sector in the effort to achieve food security in South Sudan.

Unless South Sudan cultivates a culture of self-reliance through investment in agriculture, the country is likely to remain food insecure and people cannot rely on the right to food as a human right. The right to food is not well articulated in the Transitional Constitution of the Republic of South Sudan but only the MDGs are mentioned with number one as the eradication of extreme poverty and hunger (Ministry of Justice, 2011). However, this has no force of law because a citizen cannot sue the State in a court of law for having their right to food violated when they have no means for access to food. It seems South Sudan has no legal obligation to recognize, respect, protect and promote the right to food.

Food is available and adequate in South Sudan but affordability is a challenge. High food prices are the major issue of households in South Sudan (FAO/WFP, 2014). For example, one kilogram of beef in Juba, the capital, is 800 South Sudanese pounds (SSP) while the average salary of a laborer is about 500 SSP.

With the effect of the conflict in South Sudan, it is clear that a conflict can be devastating in terms of human rights violations and abuses, and the effect these have on food production thereby causing food insecurity when crop fields become battle grounds. Peace and stability are therefore essential in order for people to concentrate on agriculture to achieve food security.

In conclusion, South Sudan has domestically limited legal obligation to recognize, respect, protect and promote the right to food as a human right because it is not explicitly stipulated in the Transitional Constitution, 2011, and neither in any other legal instrument.

The research has attempted to provide answers to the research questions with reference to the right to food as a human right. However, there are areas where further research could still be possible to increase knowledge and understanding of the complexities of achieving food security and the state’s obligation to recognize, respect, protect and promote the right to food as a human right. It is recommended that further research should be carried out to determine what would be the most important felt need of people, either to have their right to food, right to work or the right to freedom of speech respected and protected. Further research is recommended on why and how South Sudan is not producing enough food despite substantial fertile land and in view of low budgetary allocation, only 0.1% of the total budget goes to the agricultural sector. This is for decision making.

Any contribution made by this research would have been impossible without the support of University of Juba. The author is especially grateful to the Vice Chancellor, Professor John Apuruot Akec, for his encouragement; Dr. Henry Onoria for his invaluable advice and comments, and also extremely grateful to Mr. Emmanuel Joof, the Access to Justice Advisor, International Development Law Organization (IDLO) South Sudan Field Programme Office at Hamza Inn in Juba for funding the research on human rights as part of his postgraduate studies.