The controversy and conflict over cemetery places in Wolaita need scholarly and governmental attentions because displacing the existing cemeteries and emerging demands for new cemeteries due to urbanization and other factors make cemetery issues become challenging. This study intends to further explore the challenging nature of cemetery issues in rural and urban areas from different perspectives. The qualitative anthropological approach has been used to explore the issue from the local context intensively. Key informant interview, observation, and focus group discussions have been used to collect data from the field. Evidences show that urbanization together with increasing population number and limitless expansion of new religious institutions have inflated demands for new public cemetery places in urban areas. The shortage of cultivable land resource, breakdown of the early clan and family based social relation, and devaluation of sacredness of cemetery places discredited the early public cemetery places in rural areas. Rural people were forced to use cemetery and burial places arranged privately in personal land instead of using the early public cemetery arranged at clan and family level. Hence, it is understandable that emerging demands for public cemetery in the pace of urbanization and expansion of privately owned burial places in rural areas make cemetery issues complicated problem and accelerate controversy and conflict which needs research based intervention. Thus, government should establish flexible legal procedures to accommodate diverse contexts, and the government should provide the public cemetery places to all religious institutional in rural areas. The government should also inform the rural people about the socio-economic and environmental impacts of using privately owned cemetery places. The geological, environmental, health, and other contaminating potential of cemetery places need further experiential study.

There are numerous scholarly researches on the issue of cemetery from different perspectives. It is understandable from the analysis of insightful views in multiple literatures that cemetery has been conceived of as a burial place where the dead body or corpses of deceased person are buried with respect to the social, cultural, and religious context of the societies (CABE, 2007; Eriksson, 2010; Grant, 2006; Neckel et al., 2016; Salisbury, 2002). Actually, cemetery becomes more than an ad hoc site in which the disposal of human remains has taken place. Its purpose as a site of burial has been formally defined and constitutes customary religious rituals and cultural funeral practices (Rugg, 2000), and often evokes a sense of spirituality (Salisbury, 2002).

In one way or another, a cemetery is viewed as a sacred place and the usage of cemetery places depends on such sacral conception in the culture of different societies (Eriksson, 2010; Rugg, 2000; Francis, 2003). Cemetery is the appropriate sacred space where the living and dead are separated and symbolically joined as one people through the performance of transition and memorial rites (Francis, 2003). It is a fact that cemetery place is part of the sacred sites which are socially constructed, culturally defined, and generally linked to traditional religious institutions of indigenous communities (Doffana, 2014). Furthermore, cemetery landscapes mirror the past life and historic eras through which the community has passed (Francis, 2003).

There are varieties of evidences for the existence of shared cultural values, beliefs, and norms which are taken as the point of reference for the arrangement and management of cemetery among the world societies. The societal conception of the overall ritualized practices of cemetery originated from such shared cultural values, beliefs, and norms. Moreover, as noted by CABE the management of cemetery is particularly a sensitive issue in multicultural society (CABE, 2007), and its significance is not uniform over all cultures (Rugg, 2000). Recent scholarly researches viewed that the efficient management of cemeteries and neighborhoods as essential to control the environmental, social, and ecological impacts (Niţă et al., 2013) … and improper management of cemetery sites poses a major environmental threat (Neckel et al., 2016). Analytically investigating how planning for cemeteries is challenging issue in Australia, Marshal and Rounds (2010) argued that planning for cemeteries is not purely a land use issue in the legislative and physical sense; there are environmental, social, cultural, religious and economic issues which also need to be considered.

The scholarly researches such as Terms (2016), Thorsheim (2011), Tudor et al. (2013), Practice Guide (2016), Neckel et al. (2016), and Üçisik and Rushbrook (1998) conducted in different parts of the world have identified the existence of natural process of multidimensional interaction and cause-effect relationship between cemetery places and adjacent environment. Those scholarly researches pointed out that the decomposition of humans body remains in cemetery places have tendency to impose deteriorative pollution and contaminating impacts on the environment including water bodies which in turn result in health problems to the people in the residential areas. According to those researches it is believed that cemetery places need preplanned effective management to mitigate the pollution and other socioeconomic impacts. Furthermore, the research conducted by Tudor et al. (2013) viewed that cemeteries are microbiologically contaminated sites that can affect people psychologically, especially those who are living close to cemeteries. This research also identified the impacts of cemetery on human wellbeing in terms of urban landscape deterioration, health, and management.

The analysis of literatures on cemetery issues shows that potential scholarly attention has been given to the sacredness, ownership, grave arts, symbolic and heritage values, geological and hydrological properties, polluting impacts, and funerary ceremonies associated with cemetery in different parts of the world (CABE, 2007; Grant, 2006; Rugg, 2000; Eriksson, 2010; Üçisik and Rushbrook, 1998; Terms, 2016; Thorsheim, 2011; Tudor et al., 2013; Neckel et al., 2016; Üçisik and Rushbrook, 1998). But, scholarly attentions on cemetery issues are scanty in the context of Ethiopia including this study area in Wolaita. Furthermore, although they are not the concern of this study, the geological and hydrological aspects and the polluting impacts of cemetery are suggestible for future rigorous research.

Evidences show that the controversy and conflicts related with displacing the existing cemetery and emerging demands for new cemetery have not yet get the substantial scholarly and governmental emphasis as sensitivity of the issues in the study area. Taking this into consideration, this study strives to intensively investigate the procedures of displacing existing cemeteries, handling arising conflicts and emerging demands for new cemetery places, and the ownership of cemetery from the actual context of the study area. It is believed that the handling mechanism of recurrent conflicts and emerging demands for new cemetery places also need research based justification.

The trend of using cemetery places in most rural areas has been changed and going out of the tradition and norms of the society. Hence, this study also gives due attention to examine the actualized changes in terms of ownership and sacral values given to cemetery places. Currently the ownership and credential values of sacredness of cemetery have been affected by the historic changes taking place in unusual manner. Regarding this, the study conducted by Rugg (2000) points out that the ownership of the site as well as the trends of management practices could be changed depending on the defined reasons of generation to dispose the dead in particular cemetery landscape, and even the site itself could get the higher or lesser degree of sacral values when societal attitude towards the dead is shifted. Accordingly, examining the changes in the status of burial and funerary in British, CABE argued that the traditional churchyard, cemetery or burial grounds were seriously in weakened position (CABE, 2007: 5).

Thus, the researcher initiated to investigate the changes occurring and current instance of cemetery in the actual context of Wolaita.

Besides, the researcher has given emphasis to intensively explore the controversy over public and privately owned cemetery places. This study identified that the dissolution of early networked social relations at family and clan levels is one of the factors resulting in conflicts over cemetery places in rural areas. In addition, the overwhelmingly expansion of urbanization to rural areas is considered as the potential factor which needs strategic approach and applicable legal procedure to manage cemetery itself and conflict over it. The private cemetery places in the rural areas are widely exposed to displacement due to urbanization and implementation of development projects that in turn discard the heritage values and historic information. Therefore, this study aims to describe critically the issue of cemetery in Wolaita taking into account the overall above mentioned points.

Cemetery in the context of Wolaita

As mentioned in the introductory part of this paper, the term ‘cemetery’ is conceptualized as the burial place where the body of deceased person (corpse) is buried in the culture of different societies. However, the concept of cemetery in the context of the Wolaita people is not equivalent to cemetery in English language. In Wolaita cemetery is conceived differently depending on the age of the deceased person and the appropriate burial places. For instance, if the deceased person is matured his/her corpse is buried in public burial place which is locally termed “makaana”. On the other hand, if the deceased person is a child the corpse is taken to be buried in family’s garden inside enset plants; this specific place arranged in the garden is locally termed “koonuwaa”. In fact, “makaana” is commonly used by all the family members of each clan and relatives with blood relationship. Broadly in the context of Wolaita, the term “makaana” constitutes equivalent meaning of cemetery in English term meaning public burial place since it is arranged to and commonly used by the wide range family members of clans and relatives with blood relationship. Contrarily the term “koonuwaa” is used to mean the particular burial place arranged privately in the parent’s garden where the corpse of a child has been buried.

The selected elderly informants provided insightful information for the existence of visible difference between “makaana” and “koonuwaa” in terms of usage as burial places as well as in terms of the values and beliefs people associate to each. Traditionally, the Wolaita people believe that their ancestral spirits with super natural power exist for generations in “makaana”. Because of this belief in ancestral spirits, “makaana” is still perceived as sacred public burial place though its sacral values are becoming declined. Traditionally believing ancestral spirits endure its supernatural power on trees; people plant different trees on each grave. In the case of “koonuwaa”, people plant enset plants instead of trees without such sacral conceptions and believing in the upcoming of ancestral spirits with its super natural power.

In this regard cemetery as public burial place in Wolaita cannot be understood exclusively from the beliefs in ancestral spirits and sacral conceptions since each clan members have their own cemetery separately with belief in particular ancestral spirit. However, the elderly key informants including religious leaders stated that the introduction of the Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant Christianity religions strongly influenced the trends of using early public cemetery to be weakened. The analysis of data from the same sources and the vivid realities observed in rural and urban areas notify that all Orthodox Christians use cemetery arranged as public burial place in church yards. There are also public cemeteries of Muslim community in some urban and rural areas, though the communities are small in number in comparison with Christians. But, except in urban areas it is uncommon to see public cemetery of Catholic and Protestant Christians and individuals who have no membership to any institutionalized religious institutions in rural areas. Therefore, it is arguable that currently in the context of Wolaita public cemeteries are most commonly used by the Catholic, Orthodox, and protestant Christians in urban and rural areas and Muslims in urban and rural areas, but the Catholic and Protestant Christians in rural areas have no institutionally recognized cemetery places.

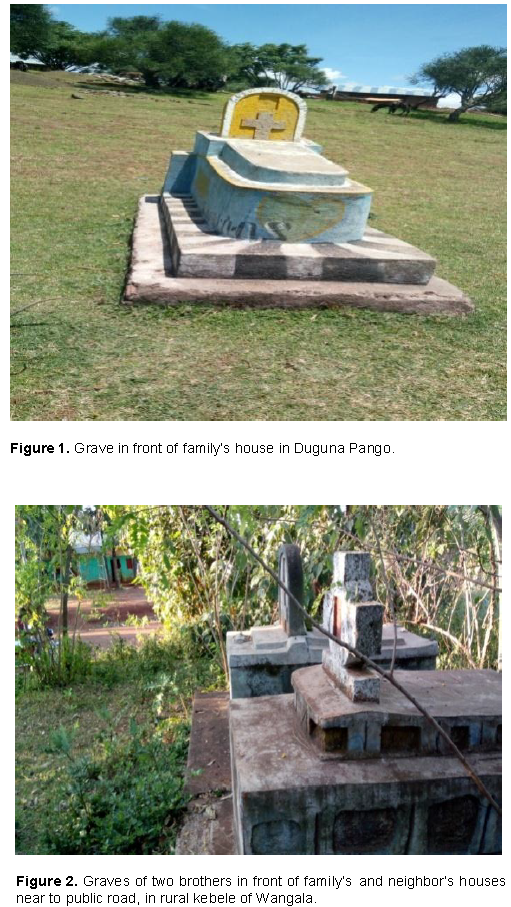

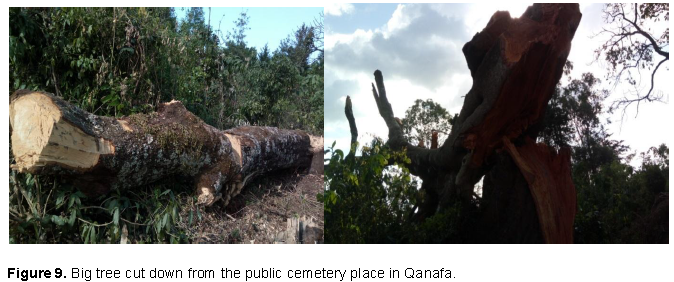

To classify and describe the diverse nature of cemetery in the context of Wolaita, the term ‘public cemetery’ is used to mean all the burial places under the ownership of religious institutions, municipalities in urban areas, the family members of some clans in rural areas, whereas the term ‘private cemetery’ is used to mean all the burial places under the ownership of the given family. The cemeteries under the ownership of religious institutions, municipalities, and family members of some clans in the rural areas were termed as public cemeteries because they are commonly used by the community at large with respect to the criterion set by the owning body of each type of cemetery. The cemeteries under the ownership of the given family were termed as private cemeteries since it is arranged in one’s own personal land and used by only the members of such family. The handful evidences show that the private cemeteries are widely expanding in almost all rural areas in unusual manner; this received emphasis in this study. Most privately owned cemeteries are exposed to disturbance because of the lack of institutional standards to manage and use the sites; this in turn fuels conflict and controversy. Currently in the rural areas private cemeteries are located close to the settlement areas, in front of each family without any affirmation from government bodies and religious institutions. Hence, as Eriksson (2010) has conceptualized such cases in Tanzania, private cemeteries owned by family members are better understood as informal burial places in the context of Wolaita (Figures 1 and 2).

Values and belief systems associated with cemetery

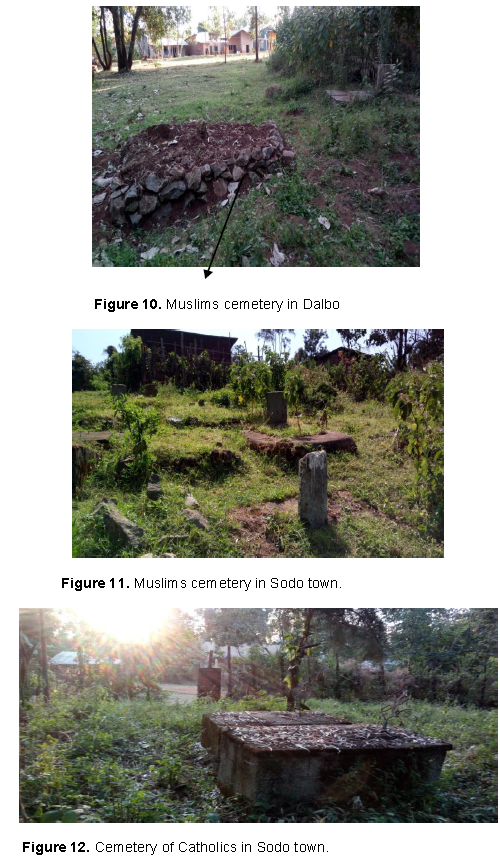

Before the introduction of Christianity, almost all Wolaita people believed in the existence of their ancestral spirits with super natural power in cemetery (makaana) which is a commonly shared burial place to all clan members who have close blood relationship. According to my elderly key informants each clan has its own ancestral spirit and all the members believe in such spirit. All the members worship and practice ritual sacrifices to their ancestral spirits. Hence, it is obvious that the societal conception of sacral power basically emanates from their belief in the existence of ancestral spirits in cemetery. Because of the society’s belief in ancestral spirit, cemetery is considered as the sacred place kept untouched for generation. The society traditionally plants different trees on top of each grave (dufuwaa) in cemetery believing that their ancestral spirits endure and exist in such trees for generations. The trees were also perceived as sacred untouchables not to be used for any other purposes. Using the land areas reserved for cemetery and trees on graves for any other purpose is considered as immoral. Culturally, Wolaita people believe that using trees in cemetery places for any other purposes brings misfortunes and bad deeds in the family’s life. This makes cemetery places sacredly remain for generations with the fearful societal care. This implies that not only the place of cemetery but also the trees on each grave were indebted to the sacral endowment carefully protected under moral domains for generations.

However, nowadays, the sacral and moral values of cemetery are becoming discredited due to changes in societal perception towards the early public cemetery declining of sacral values. In describing how the sacral values of cemetery sites were subjected to changes, Rugg understood that the sites may become increasingly sacred or less because of different factors including the general shifts in attitudes towards the dead (Rugg, 2000). Rugg’s work is acknowledgeable to further explore the current context of discredited sacral values of public cemetery places in the rural areas of Wolaita. Traditionally, in the early time cemetery places had long been arranged at clan level with strong sacral proscription. But nowadays, most of the rural people use privately arranged burial places instead of public cemetery due to changes in the trends of using land resource and declining of social values people associate with cemetery.

Types of cemeteries in Wolaita

There are potential scholarly literatures which point out the existence of public cemetery places used by all the family members for generations in different societies. Regarding this, Neckel et al. (2016) stated that there are cemeteries where members of the same family have been buried for generations. As mentioned above, in early times public cemeteries were culturally valued with great societal care in Wolaita. Informants clarified that such public cemetery places in the early time were used by all the family members of each clan for generations. However, the inevitable changes in socio-economic and belief systems declined the sacral values of public cemeteries. This geared the people in new dimensions to use cemetery in their locality.

The findings show that prior to the introduction of Orthodox Christianity to the areas the early public cemeteries at the clan and family levels took the church basement without clan and family attachments. The followers of Orthodox Christianity have developed common understanding and institutionally required to use the public cemetery places at the church yards. Because of this almost all Orthodox Christians are commonly using public cemeteries in urban and rural areas in their respective church yard. Similarly, the Catholic and Protestant Christians in the urban areas commonly use public cemetery places with institutional recognition and requirements.

On the other hand, the Catholic and Protestant Christians in the rural areas less likely use public cemetery places with institutional recognition and requirements. Of course, there are some Catholic and Protestant Christians who are still using public cemetery places arranged at clan level in the rural areas out of institutional recognition from their church. In other words, they rarely use the early clan based cemetery places as a usual trend. However, almost all Catholic and Protestant Christians including traditionalists in the rural areas use cemetery places arranged in personal or family’s land.

Conversely, in terms of advantages for societal benefit in rural areas, public cemetery is identified as the essential one for multipurpose. To illustrate evidentially, the exemplar one of such public cemetery is found in the Sodo Zuriya woreda, Qanafa kebele. According to one of the elderly informants this cemetery is commonly used by the community members who have diverse clan and religious backgrounds. He noted that community members had long been using this cemetery starting from his great grandfather. Unfortunately, currently people begin to use the trees in this cemetery for economic purpose. This in turn resulted in conflict among the community members deprived of the legitimate rights of individuals to use and keep the trees. He further expresses his disappointment and describes grievance as:

“The tree is on top of my great grand father’s grave. I have cared this tree for years. No one loves my great grandfather more than me and my families. I know that it is immoral to use the tree in cemetery places for any other purposes. I have the right to use and protect this tree. Depriving this right is unthinkable to tolerate in normal circumstance’’.

This is one of the indications to what extent cemetery is becoming conflicting issue between the government and local community. The local community has no awareness to the limit of their right over cemetery and the legal procedure has also not taken societal understanding.

The findings also imply that the public cemetery places in the rural areas of the study are neglected because of inevitable socio-economic changes taking place in their actual life. This negligence makes the indispensable roles of public cemetery undervalued. Focusing on the roles of public cemetery, one of the elderly key informants noted that:

Public cemetery is the place where individuals who have no parental land in the area can get respectful consideration to burial right. Even the passerby individual who is strange and dies accidentally gets the right to be buried in public cemetery respectfully in the culture of Wolaita people.

Practically evidences illustrate that there are some members of the community with special cases who have no parental land at all, even for burials. Most of the elderly key informants in rural areas critically explained that individuals who sold their parental and/or personal land to any other person and changed their settlement areas for long period of time lost the rightful appropriate burial place. In case when life is becoming challenging, these persons are forced to return back to their original settlement areas but they cannot get burial place since they have already sold their parental/personal land.

In the session of FGD, informants rigorously explained that the introduction of Christianity in general and Protestantism in particular seriously influenced the trends of using the early public cemeteries in Wolaita. All the community members who primarily converted into Orthodox Christianity begun to use cemetery places arranged in church yard neglecting previous public cemeteries. Through time the expansion of Orthodox Christianity influenced people to less value the public cemeteries, and instead use cemeteries arranged in the church yards. The informants also elaborated that the later conversion of Orthodox Christians into Protestantism expanded denial to the early public cemeteries and facilitated the expansion of privately owned cemetery places in rural areas.

Based on the evidence, almost all rural areas people use cemeteries arranged privately. There are large members of the community who are using privately arranged burial places in personal and/or parental land close to their settlement areas. They reason out different factors for the usage and arrangement of cemetery privately neglecting the early public cemeteries. Based on their justification and the critical analysis of data collected from the actual life context of the society, it is undoubtedly believed that the increasing population number, change in belief systems, and the breakdown of multidimensional social connectedness at clan level are the significant factors that force people to use privately arranged cemetery places in rural areas.

Due to such changes in the trends of usage of cemetery places, the contradiction, controversy, and conflict over cemetery places are becoming widely observed in different rural areas. The working legal procedure gives more emphasis to cemetery issues in urban areas than rural areas. This adheres to illusion to define the rights of privately owned cemetery. The limitation in legal procedure regarding compensation payment makes it ambiguous and difficult to apply; on the other hand the right to administering and using burial places has been left under question.

Generally, the findings imply that the classification of cemeteries in Wolaita is more similar with that of Eriksson's classification of the cemeteries in Tanzania with the exception of crematory. In case of Tanzania, Eriksson has noted the categories of cemetery as municipality owned, local community or religious community owned, family owned or informal, and crematory. For the sake of broadly classifying cemeteries in the context of Wolaita, it seems appropriate to classify cemeteries into two categories as public and private cemeteries. Public cemetery includes the municipality, religious institutions, and some family members of clans owned cemeteries, whereas private cemetery includes privately owned cemetery places arranged in the compound of family/personal land.

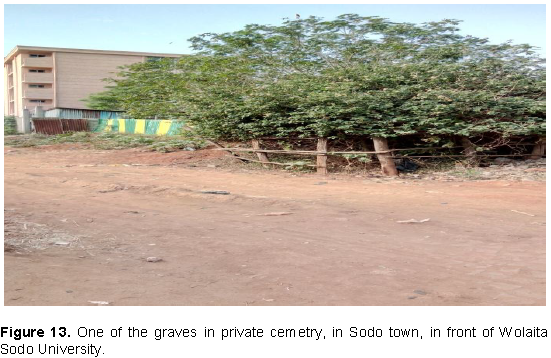

Municipality owned cemetery is only found in Wolaita Sodo town, specifically located in Markato sub-city, but it accommodates cases from all the three sub city of the town. It is reserved for individuals who have no membership to any officially recognized religious institutions individuals who are strange to the area and died accidentally. Religious institutions owned cemeteries were established under the Orthodox, Catholic, Protestant, and Muslims religious institutions. All the Orthodox churches in rural and urban areas have cemeteries with institutional management. Similarly, all the Catholic and Protestant religious institutions in urban areas have their own institutionally managed cemetery places. The Catholics and Protestants have cemeteries separately in urban areas, whereas in the rural areas they are using privately arranged cemeteries. The information from municipalities and religious leader points out that the followers of different sects of Protestantism use the same cemetery places in urban areas because it is difficult to provide the appropriate land area for cemetery to all sects separately. Thus, different sects of Protestant religion formally recognized under the Office of Evangelical churches in Wolaita convinced them to use the same cemetery places in urban areas. The good example of the Protestants cemetery which is commonly used by all the members of about eight (8) sects is found in Wolaita Sodo town, specifically in the compound of Mebrat Hail Kalehiwot church. Most of the Muslim communities in urban areas and few members in the specific rural area of Dalbo have also their own cemetery places used commonly in their respective areas.

Private cemetery places are most commonly used by the Catholics and Protestants in the rural areas because the followers traditionally use their family/personal land areas for burial. The management of cemeteries and arrangement of burial places privately in rural areas lacks legal and institutional standards in comparison to public cemeteries in urban areas (Figures 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8).

Generally, cemeteries issues have not still get formal governmental attention with legal procedures which must be considered as abiding tool to refer to in the usage of cemetery places for burials in rural areas. We can easily observe privately owned burial places in the personal land here and there in the compound of each family, even in the area close to towns. These burial places are exposed to disturbance due to the expansion of urbanization and associated developmental projects implementation required to benefit urban societies which make cemetery issues controversial and a paradox.

Cemetery places in rural areas

In the early times public cemetery places arranged at the clan levels were common in the rural areas of Wolaita. Those public cemetery places since then were kept with the strong sacral conceptions carefully for generations. However, currently the early public cemetery places in rural areas have been neglected due to the increasing number of population, shortage of cultivable land, and disintegration of networked social relation among the members of families and clans. Even currently people use cemetery places for crop production and trees on the graves are being used for other purposes like domestic fire and house construction (Figure 9).

When the parental land is allocated and reallocated from generation to generation, the children get small portion of agricultural land to serve their life. This forces the children to settle and establish their own family separately outside the compound of their parental land. This increases the tendency of reduction and breakdown of the earl intimate social relation among the members of family and clans. Besides, these result in the conflict of interest over land resource among the family and clan members who have long been using the same cemetery place commonly in the past. In the context of this study the term family is used to mean the early extended family members including all the relatives living together in the same residential areas and sharing the same cemetery place.

Even though the usage of public cemetery places has been neglected in the rural areas, the findings imply that there are rarely observable public cemetery places traditionally used by some of the community members without institutional base. But most of the Catholic and Protestant religious institutions in the rural areas lack public cemetery places with institutional baseline. All the Catholics and Protestants use privately arranged burial places in the compound of their personal land. It is uncommon to see the public cemetery places under the ownership of Catholic and Protestant religious institutions in rural areas because the followers have not been institutionally required to do so as that of Orthodox religious institutions. On the other hand, all Orthodox religious institutions in rural areas use the public cemetery places with institutional standards. Since the Orthodox Christians are institutionally required to fulfill the overall criterions, the church leaders take responsibility to arrange cemetery places. There are also public cemetery places under the ownership of Islamic religious institution in rural area of Dalbo.

Cemetery places in urban areas

Diverse literatures provide sensible justifications regarding accessibility of cemetery places, especially in urban areas examining the effects of urbanization. It is believed that getting access to sufficient cemetery places in populated urban areas is becoming difficult in different parts of the world (CABE, 2007; Üçisik and Rushbrook, 1998). To this, Eriksson’s study in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania gives exemplar confirmation of the reality of cemetery issues in urban areas. Aiming to describe the accessibility of land for cemetery, Eriksson argued that it is difficult to get access to land for cemetery and burials in the city of Dar es Salaam due to rapid urbanization (Eriksson, 2010). Accordingly, this study identified that cemetery issues are becoming sensitive and serious in urban areas of Wolaita due to the increment of population and emerging demands for new cemetery places. Hence, it is believed that cemetery issues need evidential justification in terms of urbanization and land resource management.

Based on the findings the researcher has understood that as in any other parts of Ethiopia, people in the urban areas use public cemetery places under the ownership of religious institutions and municipalities in urban areas of Wolaita. Evidences show that Municipality owned cemetery places are not common in the context of Wolaita, except one cemetery place in Sodo town. The Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant Christians and Muslims have their own public cemetery places separately in all urban areas. But the expansion of urbanization and emerging demands for new cemetery places from different religious institutions make cemetery one of the challenging issues to government bodies in the urban areas.

The findings imply that urbanization with increasing population number creates good opportunities for the establishment of different religious institutions which enhance demands for new public cemetery in urban areas. In the study area, urbanization has pushed the rural people from their settlement areas and also increased the tendency to disintegrate their clan and family based social connectedness. The expansion of urbanization makes cemetery places previously located outside the center of towns and in different rural areas encircled by urban population and exposed to disturbance and displacement. The Catholics cemetery in Sodo town, Muslims cemetery in Sodo and Dalbo towns, and privately owned cemetery places were previously located outside the center of towns in the rural areas but currently encircled by urban population. This caused discomfort to the people living close to such cemetery places and chaotic disregard to the sacral values of cemeteries. Figures 10, 11 and 12 show the encircled cemetery places by urban population.

Actually the demand for new burial places emanates broadly from newly established religious institutions. The information from municipalities and other zonal administration offices elaborates that demands from newly established religious institutions are becoming difficult to manage due to the increasing number of such religious institutions and shortage of accessible land resources in urban areas. Thus, the emerging demands for new burial places and displacing the existing cemetery in the pace of overwhelming urbanization create recurrent conflicts between the government bodies and the local community. Displacing the existing cemetery accelerates socially acceptable questions with complaints which need answers with practical justification from concerned government bodies. These questions are most commonly stressing on the sacral values and compensation payment to displaced cemetery. The findings notify that the sacred value of cemetery is becoming undervalued when it is displaced though it is conceived of as untouchable by the society. On the other hand the legal procedure of compensation payment is impractical with regard to societal demands because it is rigid to accommodate diverse contexts which make it out of the logic for practicality.

Although the issues of cemetery is becoming challenging in the study areas, the controversy and conflicts could be handled smoothly in urban areas with the exception of difficulty to access appropriate land areas. This is because since we have public cemetery under the management of religious institutions and municipalities, the emerging demands for new cemetery and compensation to displaced cemeteries could be managed following the working legal procedures at institutional levels in urban areas.

In fact, the information gathered from different religious institutions and municipalities implies the existence of concrete evidence for less complication of the issue in urban areas. To exemplify, in the cases of Teklehaimanot in Sodo town the management of cemetery places including displacing the existing graves and collecting as well as moving the fossilized body remain to appropriate places have been smoothly held through the communication at institutional level. The overall collected body remains are re-buried in single new grave to preserve such fossilized body remains in secured place for generations. This is aimed to keep the security of fossilized body remains in graves sacredly for generation. This is because most of the displaced graves were old aged, less secured, and exposed to any external disturbance. Of course, this has invaluable contribution to make land resource manageable to accommodate the future demands for cemetery places. Generally, it is arguable that in urban areas cemetery issues took institutional base submissively to the institutional procedures under municipalities and religious institutions.

Legal procedures, compensation payment, and displaced cemeteries

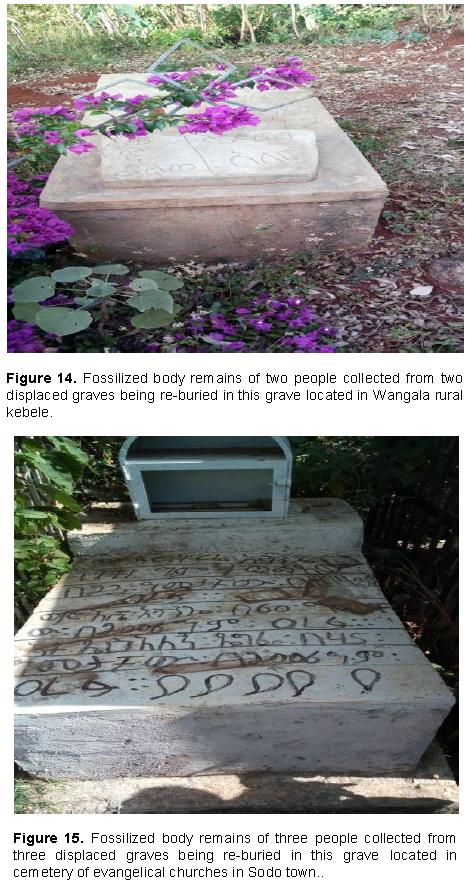

The working legal procedures (SNNPRS, 2017) enacted by the regional government of Southern Ethiopia less likely clarify the process of compensation payment to displaced graves in the given cemetery because of its rigidity to accommodate diverse contexts. This rigidity makes such legal procedure difficult to reconcile with demands for compensation to displaced graves from different cemeteries and burial places. The researcher has identified rich evidences for the existence of displaced graves in the rural and urban areas of this study. Unfortunately, in some rural areas the innocent rural community members were neglected to get compensation even to cover the expenses to move displaced graves to new cemetery. For instance, there are four private graves displaced without any compensation in the rural kebele of Koysha wangala, Humbo Tebela district. The graves were displaced in the time of implementing road construction project but the family members were denied access to get compensation by the owners of the project. The family members were forced to displace the graves and move the fossilized body remains to other cemetery places by covering all the expenses. In this regard it is difficult to cover all the expenses to displace and move graves without compensation. To minimize the expense, economically incapable family members make culturally unusual decision to bury the body remains of different people collected from different graves together into one grave, though it is going out of the norms in the cultural context of the society (Figure 14).

Through observation, the researcher could identify numerous cemeteries and burial places displaced in different urban and rural areas of this study. Regarding those displaced cemeteries and burial places, the information from concerned government offices and the local community members indicate that the cemeteries were displaced due to the expansion of urban areas and implementation of development projects. It is obvious that the expansion of urbanization needs the implementation of different projects for infrastructural development to benefit people in urban areas. For instance, the researcher has personally observed that urbanization increased demands for road construction, installation of water and electric lines, establishing schools and health centers, and others in Sodo town and other urban areas. Hence, urbanization can be viewed as influential factor for displacement of cemeteries.

Actually, the information obtained from the concerned government bodies points out that the working legal procedures to displace cemetery places are becoming less justifiable and impractical. Because, the legal procedures give more emphasis to the amount of compensation to be paid for displaced graves than the socio-cultural context and the ownership rights of privately owned cemeteries in personal land. This accelerates conflict and makes the issue more sensitive than ever in Wolaita. In the legal procedures, the amount of compensation has been set only to cover the expenses of displacing the exiting graves and moving the corpse to newly arranged burial place. Besides, the legal procedure encourages project owners to divert the direction of project implementation out of the normal plan instead of paying compensation by displacing graves in burial places. If there are graves in the planed areas to implement projects, the owners of such project prefer to divert the direction of projects.

Surprisingly, the researcher has identified the handful evidences for the diversion of the direction of road construction out of planed designs of the project in front of the main gate of Wolaita Sodo University, in the left side near asphalt road from Wolaita Sodo town to Arbaminch town. In this specific area, there is one grave in the middle of the road planned for coble stone construction by the municipality of Sodo town. When the project owners required to construct the planned coble stone road were reaching the area of this grave, the family members of the deceased persons began asking for compensation. In this time the project owners decided to divert the direction of this road instead of paying compensation. At the end the project owners diverted the direction of road to the left side out of the planned design of the project (Figure 13).

During the field work, the researcher also found a number of graves displaced from cemetery places in rural areas because of urbanization and implementation of road construction projects planned to connect rural kebeles with towns of woreda and zonal administrative centers. For example, in Humbo woreda, Koysha Wangala kebele four graves, in Kindo Koysha woreda, Man’’ara and Sortto kebele about fifteen graves, in Duguna Fango woreda near Bitena town three graves have been displaced. In the case of graves displaced in Kindo Koysha woreda and Duguna Fango compensation has been paid to the family members by the project owners. Unfortunately, in the case of graves displaces from Koysha Wangala compensation has not been paid to the family members. Unlawfully, government bodies of the woreda together with project owners forced the family members to displace the grave and move the fossil remains (corpse) to other burial place orienting them as no legal ground to pay the compensation since the project is for societal benefit. Hence, the innocent family members who have no ideas about the legal grounds and their rights regarding cemetery places in their personal land forcefully covered all the expenses personally with the support of community members in displacing the existing graves and moving the fossil remains to the graves in the other places. This is the implication for absence of fairness in the application legal procedures and lack of societal awareness about the legal procedures. Figures 14 and 15 show Koysha Wangala grave of the body remains of two people.

Basically, it may be difficult to pay compensation from the budget funded for development projects unless it is planned at the very beginning. The working legal procedure regarding compensation is rigid to apply in the diverse contexts. On the other hand, the question of the local community for compensation is also not blamable since it has the cultural and humanistic grounds at least to cover the expenses to move the corpse from displaced graves to other areas. Lack of essential attention of government bodies to cemetery places especially in the rural areas, rigidity in legal procedures, and unconsciousness of local community about the legal ground grounds and impacts of using privately owned cemetery places aggregately make cemetery issue more complicated phenomenon which needs strategic intervention.

The handful evidences disclose the existence of limitations in the current working legal procedure in terms of managing the emerging demands for cemetery, displacing existing cemetery, and compensation payment. Therefore, the legal procedure should consider the socio- cultural contexts and economic backgrounds of the community members in the time of displacing and moving the graves. It is believed that since it is socially and culturally the usual deed to use cemetery places for burials, compensation should be paid at least to cover the expenses for displaced graves. One of the elderly informants who have been affected by displacement of cemetery place expresses his compliant as, Nuni orde mishsha oychchoko maanassi uyanassi metotikoka. Dufuwaa laalid hara dufuwaa bokid assa meqetta moganasi koshiyaba kowotettay kunttanasi bessesi. Literally it is translated as, we are not asking for extra money though we are in difficulty to eat or drink. The government should pay compensation to cover all the expenses to displace the graves and move the body remains to the other burial places. Besides, one of the key informants in Koysha Wanga kebele who is forced to cover all the expenses personally notes the unfairness of compensation payment as the government put unexpected economic and social burden on me as punishment for no mistake I did. This is the implication for limitation in legal procedure of compensation payment.

Generally, the legal procedure has not been fully implemented to the ground in the actual life of the community, even in urban areas. It states clearly how long the fossilized remains of dead body should stay and be moved from the given burial place to the other secured burial places for preservation. But in reality, moving the remains of dead body from the existing grave to the other secured places is uncommon to see unless it is planned officially for the purpose of development projects implementation in urban areas. In fact it may have its own advantages to economically use land resource, handle the arising conflicts and emerging demands for new cemetery places. However, it is unbelievable to realize this unless the government bodies, religious institution, and elderly community members work hand in hand to create public awareness about the usage of cemetery places from legal perspectives.

Advantages and disadvantages of public and private cemetery

The practical evidences identified from the field clearly show the advantages and disadvantages of public and private burial places in the context Wolaita. To pinpoint the advantages and disadvantages, the public and private cemeteries have been described in terms of land resource utilization, urbanization, development projects implementation, handling arising conflicts and emerging demands for new cemetery places, and preservation of cemetery as memorial heritages with historical significance. By comparing and contrasting the public and private cemeteries, the elderly community members notified that using the public cemetery is by fur advantageous than private cemetery for burials. Regarding this, the impressing explanation given by one of my elderly key informants, is narrated as follows in local language:

Goyyanaw mizaa hemanaw bittay baynaasan dufuwaa penggiyan penggiyan idimidi uttiyogaan go’’aay baawa. Duufooy penggiyan diko ayyiyanne awaay bantta natussi wonttan qamaan dufuwaa xelidi dagamidi, afuxxidinne, kayyottidi dusaaw hidotaa xayosona. Asa meqetti al’’o gidyo gishaaw duufoy bonchetid dere gutaraan daanaw koshshesi. When translated to English, it is not good to have graves privately in front of the parents’ compound since there is shortage of cultivable and grazing land. Looking the graves in front of their compound in day and night times aggravates the parents to be disappointed, cry, and stressed feeling no promising futurity to their life. Since the body of human being is respectable, it is better to have graves in public cemetery carefully.

This implies that using public cemetery places is more advantageous to economically use scarce land resource and provides social and psychological benefits to the family members.

Actually, the family members of deceased person may consider and feel that putting the graves of their relatives in front of their compounds as respect, but the dynamic changes occur in their actual life disturbs the sustenance of graves with historic information. Because graves in privately owned cemetery places are highly exposed to displacement this discards the heritage values of cemetery places. Using public cemetery places under the ownership of the municipality and religious institutions are easy to manage, even to displace if needed, following institutional procedures. The concerned government bodies make and apply any decisions for societal benefit and handle conflicts as much as possible. Generally using public cemetery is more advantageous than privately owned cemetery places both in rural and urban areas.