ABSTRACT

In Agni society in Côte d'Ivoire in general, we are increasingly witnessing the dynamics of intergenerational relationships which are often illustrated by the process of depreciation of the elderly. However, among the Agni of the Djuablin region, we note the social usefulness of the elderly through their participation in the settlement of conflicts over land management. This research therefore aims to analyze the social participation of the elderly in the settlement of land disputes in this region. In a qualitative approach, the sampling by reasoned choice made it possible to retain five (5) villages where land conflicts are rife on a recurring basis. Over a discontinuous period of three months, from March 11 to June 15, 2020, semi-structured individual and group interviews were conducted with 30 actors, including 10 aged 60 or over (village chiefs and notables) and 20 other actors: Collective and institutional. From the thematic analysis of the speeches, it emerges that the Agni have various representations of the earth: An inalienable good, soul, life, wealth and the reproduction of social identity. Also, the absence of laws following the independence of Côte d'Ivoire, the new legal provisions for the appropriation of land, the juxtaposition of customary and modern systems of succession, the modification of the social environment, resulting from urbanization have been cited as the origins of conflicts. These break down into intra-group or intra-family conflicts within the same group or family. The resolution of these conflicts requires the participation of the elderly, with regard to the social prestige linked to their status as patriarchs and their relationship to the divinity who legitimizes their power.

Key words: Social participation, elderly, land conflicts, Côte d'Ivoire.

The economic and political changes affecting all social structures have contributed to reconsidering among certain peoples of the Ivory Coast the social roles and position occupied by the elderly. We are increasingly witnessing the dynamics of intergenerational relationships which are often illustrated by the process of depreciation of the elderly. Age, both a natural and cultural parameter, engages a series of dimensions: structural (social relations that are built on the basis of age), strategic (age could be mobilized to achieve objectives and plans for position oneself in the social field), ideological (age can structure beliefs, standards, values, perceptions, discourses, social practices, in other words, social representations) and symbolic (categorization from age: the oldest are the wisest). This whole series configures its interest and importance in Africa in general and in Côte d'Ivoire in particular. However, with the profound socio-cultural and economic changes underway, the representations which, until now have structured the relationship with old age, are changing and posing new challenges in terms of intergenerational balance.

Indeed, these representations, consequences of the various orientations put in place (political, economic, cultural and educational), relating to social, community and family structures, have undergone profound changes. These are characterized by the intrusion of modern social forms which have made it possible to lead to a coexistence of customary social structures (royalty, chiefdom, notability, tribe, lineage, clan, undivided family, etc.) and modern social structures (council regional, prefecture and sub-prefecture, town hall, tribunal, etc.) which can be observed in Côte d'Ivoire. This situation has not been without impact on certain categories of the population, in particular, the most vulnerable members of society. Children, women, people with disabilities and especially the elderly who were, at one time, considered to be the linchpins in decision-making spheres, are faced with a loss of recognition. The consequence seems to be the negation of cultural foundations and the reappearance of new models like those of the West, for example, in various areas of society. In this context, therefore, the elderly are relegated from a position of sacralization, from which they were presented as the pivots of societies and their ancestral traditions to those of simple members. These elderly people go from being the guarantors of their sustainability and their symbolic and material survival to that of exclusion from the main social roles they previously played. In Agni society in Côte d'Ivoire in general, these findings can be observed in the reduction of the decision-making field of seniors who are nowadays losing their control over material, matrimonial and symbolic resources. However, in the Djuablin region, a place of diverse social transactions and pluralistic logics (where quest, self-assertion and private accumulation of wealth dominate), it is observed that seniors continue to participate socially. This region of constant competition due to its strategic position (border region with Ghana) and investment opportunities (coffee, cocoa, rubber tree cultivation, oil palm, food products, etc.), receives requests for use of its earthly space. This favors the scarcity of land, and also the emergence of intra-family, inter-community conflicts, putting the elderly in the first place in the settlement process, despite the existence of a modern system for settling conflicts (Police, Gendarmerie, Sub-Prefecture…). Indeed, it is clear that certain endogenous institutions such as royalty, the chiefdom and its notability still survive in this social space and continue to value the elderly. It is these older people who, from a structural point of view, by virtue of their status and roles, constitute the main actors of these social institutions. From a symbolic point of view, the socio-cultural practices mobilized by the elders with reference to the ideology (representations, beliefs, etc.) conveyed in their social frameworks often induce happy outcomes in the settlement of land conflicts which often oppose individual and collective actors and institutional. This is illustrated by the village chiefs who, according to Bagayoko and Koné (2017), were able to be mobilized to intervene in the management of much more political Ivorian conflicts. As Boubacar et al. (2010) underlines: “through an unexpected return, the weight of traditional chiefs as moral authorities, both in the eyes of the populations and of the rulers at the top of the state, enables them to settle disputes which normally fall within the competence of state institutions (…). In Niger, for example, missions led by representatives of the highly respected Association of Traditional Chiefs of Niger have helped resolve political crises on several occasions". Also, a study conducted by Adou (2012) reports the active involvement of the kings and chiefs of Côte d'Ivoire, through their associations, in peace initiatives at the local level. And as mentioned by Bagayoko and Koné (2017), one of the most visible and beneficial uses of traditional conflict management mechanisms in Ivorian society has been the effective involvement of traditional power structures (mainly led by the elderly) in social stability during the long period of conflict that the country went through. These elders will be effective conciliators in the local conflicts of the period opposing indigenous and non-indigenous peoples. In this context, therefore, seniors are still the subject of many considerations. At advanced age (60 years and beyond), are attached the values of respect and courtesy in the order of knowledge, morals and the exercise of political, economic, social, cultural and religious powers (Tanoh, 2014; Dayoro, 2008; Kacou, 2013; Ebénézer, 2009). In this regard, issues related to the elderly have been the subject of several studies mainly under three approaches. The first issues were concerned with institutional offers and the living conditions of retirees in Côte d'Ivoire (Dayoro, 2008; Ossiri et al., 2017). Then, socio-anthropological studies have been devoted to the question of the survival of institutions for the valorization of the elderly such as the ébêb in Odjukru society (Kacou, 2013) and to the mistreatment of the elderly linked to intergenerational conflicts (Tanoh, 2014). Most of these studies either opened up unresolved questions about older people's relationships to politics or observed them as “mirrors of the social game (Dayoro, 2008; Kacou, 2013; Tanoh, 2014). These three approaches have the advantage of presenting the importance of this category in question, in this case, the institutional, political, cultural, religious and social dimension. However, we can always, in the extension of these, question the updating and maintenance of the elderly in social and economic negotiations in a context of modernity, thus calling into question the paradigm of decline of the third age stated by Lefrancois (2007). We then have to ask the following question: what roles do the elderly play in the settlement of land disputes in the Djuablin region of Côte d’Ivoire?

The general objective of this research is therefore to analyze the social participation of the elderly in terms of the roles played in the settlement of land conflicts. More specifically, it is about:

(1) identify the social representations of land among the Agni of Djuablin;

(2) identify the origins, natures and typologies of land conflicts;

(3) investigate the roles played by the elderly in resolving conflicts over land management.

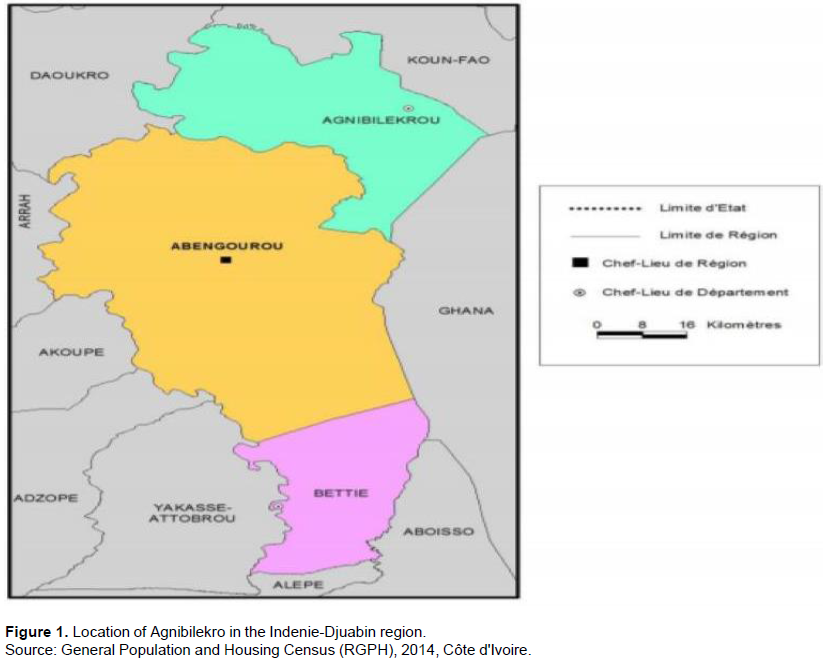

The study took place in the district of Comoé, precisely in the region of Djuablin located in the east of the Ivory Coast. This is limited to the north by the Gontougo region, to the south by the Mé and Moronou regions, to the west by the Ifou region and to the east by the Republic of Ghana (INS, 2014). At the administrative level, this region has three departments including Abengourou the capital, Agnibilékro and Bétié. Its cosmopolitan population of indigenous and non-indigenous people is estimated at 560,432 inhabitants (INS, 2014). The study took place in five villages in Agnibilékro, a town 270 km from Abidjan. This city borders with Ghana and is mainly populated by Agni-Djuablin. According to the same sources, its economy is essentially based on agriculture which constitutes its main wealth. The main products of the region are perennial crops (mainly cocoa and coffee) and food crops (plantains, yams, cassava, vegetables, rice, fruit and market garden products, etc). In this context, the land use rates are particularly high. This generates many land conflicts whose resolution requires the involvement of the elderly, holders of cultural, social, economic and symbolic capital. It is to better understand the social utility of the elderly through their contribution to the resolution of these land conflicts that five villages where these conflicts are very recurrent were selected for this study (Figure 1).

The investigations were carried out in 5 villages in this region. In an essentially qualitative approach, sampling by reasoned choice made it possible to retain these villages. This non-probability sampling procedure consisted in selecting participants, that is to say villages where land conflicts are rife. The choice of these villages was made on the basis of data provided by the customary authorities of the said region. The 10 senior actors aged 60 or over from these five villages are considered typical of the target population. They were chosen on the basis of specific criteria such as their participation in the settlement of land conflicts of the intra-family and inter-community type despite the existence of a modern conflict settlement system (Police, Gendarmerie, Sub-Prefecture, etc). Thus, this qualitative sample was oriented or targeted rather than drawn at random. In total, the study involved 30 actors, including 10 aged 60 or over made up of village chiefs and their notables who constitute the target population. To these are added 2 judicial authorities and 3 officials of the land service and cadastre of the Ministry of Construction and Urbanization of the Djuablin region; they constitute the expert population. 5 leaders of allochthonous and non-native communities, 5 leaders of women's associations and 5 leaders of youth associations and executives from different villages constitute the control population. The choice of these collective and institutional actors is justified by their regular and experienced involvement in the resolution of land conflicts in this region. The study used tools such as semi-structured individual and group interview guides. Over a discontinuous period of three months, from March 11 to June 15, 2020, these interviews were carried out with the individual, collective and institutional actors indicated earlier. The individual interviews carried out according to the availability of the respondents were recorded using a dictaphone. With these interviewees, the interviews concerned the following themes that furnish the interview guide: social representations of land among the Agni of Djuablin; the origins, nature and typologies of land conflicts; the roles played by older people in resolving conflicts over land management. The use of manual counting as a process seemed more suited to the thematic analysis of the interview guides. It has a considerable advantage in the categorization of the variables of the different themes, in order to better appreciate the responses collected in the field of investigation. The choice of manual analysis is also justified by the fact that the study is part of a qualitative approach. Clearly, the analysis of the data collected followed the following process: transcription of the data recorded by seizure from the Microsoft Office Word 2007 software; preparation of files with codes that can identify the transcription of the interviews of the respondents; grouping of interviews by topic; construction of analysis categories and significance units. This qualitative approach involves a content analysis. This analysis turns out to be necessary and judicious as far as understanding the retention of seniors in this transitional society is concerned.

The main results of this research revolve around three major points: social representations of land among the Agni of Djuablin; the origins, natures and typologies of land conflicts; the roles played by the elderly in resolving conflicts over land management.

Social representations of land among the Agni of Djuablin

Land, an inalienable good

For most of the Agni of Djuablin, land is a fundamental wealth. It contains all the values on the political, economic, religious and cultural levels. For them, owning land is a power because it contributes to the permanence of their social organization. Seniors express themselves in these terms:

“On our land, our ancestors from Ghana settled. They arrived in Ivory Coast around the 1680s. Since those ancient times, they have organized all our royalty, our lineages, our great families and even our lives, from generation to generation around these lands. These are our possessions and we cannot pass them on or give them up to anyone” (AE, 93 years old).

From this speech, it emerges that the social, political, economic, religious and cultural organization of the Agni of Djuablin takes place around their lands. One can easily understand the extent and recurrence of the conflicting social relations that are structured around the land in this region. The land is therefore presented as an inalienable good for this people.

The earth, synonymous with "soul", life, wealth, reproduction of social identity

In Agni society, the earth is seen as "the soul". Indeed, the yam tuber, for example cultivated in the ground, is ideologically and symbolically represented there. This tuber therefore occupies a prominent place in this society. The yam festival, which is held annually there, allows these peoples to worship their land and their ancestors who bequeathed it to them as an asset and inheritance. The soul is also the spirit or the relationship that visible actors have with invisible actors (spirits, ancestors, diviners, etc). And, generally, it is the land that is worshiped and that constitutes this point of contact between the two groups of actors. Life, wealth and even identity reproduction stem from the quality of this relationship between these actors. The following speech by a patriarch illustrates this well:

"The earth is our soul! It is through her that we come into contact with our spirits, diviners and ancestors. We do nothing without invoking them. They are the ones who left us the land. Our success in everything we do comes from them. The land is therefore our whole life, it is our wealth, it is the heritage of the Agni. You can recognize the Agni by its land, its large plantations and its riches" (ET, 91 years old).

In short, owning land makes it possible to acquire material wealth which confers social prestige. The earth organizes social life or certain aspects of life are organized around the earth.

The origins, nature and typologies of land conflicts

In the Agni villages of Djuablin, land disputes have several origins. Among these, economic, cultural and political causes have emerged from the discourse. The following are noted.

Political causes linked to the absence of texts after the independence of Côte d'Ivoire

During the accession of the Ivory Coast to independence, a period essentially characterized by an absence of texts specifically governing the matter, it was thought that all the land was vacant. Freedom was thus given to all those who wished to occupy and exploit the plots of land which interested them, as long as they had the means to acquire them. The latter could all the more claim to own the said lands, especially since their approach had been favored or encouraged by political will. The following speech situates us on the question:

“Foreigners have come to settle on our land because the first President of the Republic said that the land belongs to whoever develops it. It was this law that created all the problems we have today with those who came to settle on the land our parents left us" (K.A., 88).

This speech highlights the complaint about illegal land tenure by migrants in the aftermath of Côte d'Ivoire's independence. To add to this, another denounces Ivorian civil law which favors the subsidiary succession of property to the detriment of customary law which is organized around the matrilineal system.

Cultural and economic causes: Succession systems challenged by conflicts of interest

The system of succession among the Agni follows the logic of the system of matriclans. The goods are constituted within the framework of matrilineage and are managed there by the patriarchs. This is what this elder expressed in these terms:

“With us, goods like land and plantations remain in the family. And it is the elders who manage them and who appoint the heirs. It is first the brother of the deceased who is designated as heir, and after that come the nephews, that is to say the sons of the sister of the deceased. But with the new law, it is the children of the deceased brother who must inherit. It is this law that sent a lot of land issues to our Agni families and villages" (A.J., 81years old).

From these different discourses, it emerges that the migratory phenomenon experienced by this border region and the juxtaposition of two contradictory legal systems (customary and modern) in their execution, combined with economic and social issues, have generated enough land conflicts in the region (Djuablin region). The subject of these conflicts is precisely about exploitable land.

The modification of the social environment, a consequence of urbanization

The modification of the social environment, consequent to the urbanization which inserted the village into the city, modified the economy of the village based on agricultural activity. For the respondents, the villages of Djuablin knew until very recently the existence of traditional plantation zones with the cultures of coffee, cocoa and other industrial cash crops, such as oil palm, sweet banana, as well as food crops such as cassava and yams. Urbanization has therefore acted as a brake on the development of sustainable agriculture by occupying village lands. The break with this type of economy took place at a rapid pace in the late 1960s in the Agni villages with the corollary of many conflicts. According to the respondents, a land conflict is necessarily linked to land. The evocation of the term conflict is associated with a certain number of words, namely palaver, history, dispute, disagreement, opposition, antagonism, belligerence with a person or a group of people. The following speech situates us:

"In our villages, there are too many palaver because of the land: palaver in families between nephews and their maternal uncles, palaver between children and their cousins, palaver between villagers and strangers. Eeeeeh! It’s too much. And that tires us old people. We spend all of our time settling issues between people" (BK, 87 years old).

It can be seen that the words used by the respondents refer to the different manifestations of land conflicts. In other words, they gave indicators of land conflicts, that is to say a social definition of conflict. On analysis, we realize that it necessarily takes another person for there to be a conflict. As a result, the land conflict could be understood as a social relationship. The social components within the framework of this research refer to the following conflict elements: actors, motives, manifestations. Two types of conflicts emerge as the following.

Intra-group or intra-family conflicts: Within the same group or within a family. In this case, the conflicts are generally between the nephews and the sons of the deceased (ascendant), members of the same family, members of two families or two neighbors. The different types of conflict are based on the actors of the conflict in relation to the social unit of reference: the group.

“Our customs here do not suit widows and their children at all. When a woman loses her husband, she is stripped of everything (plantation, forest, house ...) because it is neither for her nor her children to inherit the property left by the husband or biological father. It's the old people who decide everything. Very often the widow is sent home with her children. So today, with the new laws, women and their children are also standing up to claim property. And that sends a lot of problems to families and villages. There's even death in it all. People can kill you for inheritance’’ (Group interview, women and young people).

For the village authorities interviewed, intra-family conflicts are the most frequent in Djuablin. In fact, from various and multifaceted causes, these conflicts involve various actors: men and women, whether young or old, from the same family or the same clan. This is how we have either land disputes between nephews or between sons and nephews.

Intergroup conflicts: Between two or more groups (ethnic, religious, political), intracommunity or intergroup conflicts are conflicts between families or ethnic communities. They are modest compared to other types of land disputes in Djuablin. For OS (54 years old, non-native),

“When whoever gave you the land to cultivate dies, that's where the problems start with the heirs. The solution is to do the papers ... But even that too, there is too much palaver in it."

In short, for village authorities, executives and young people, land disputes between families and between neighboring communities concern family lands, clans whose limits are historically already known by each family or clan. For them, conflict occurs when there is encroachment, either voluntarily or through ignorance, on the plots of one family by another family. Depending on the oldest member and the village chief, conflicts can also arise from donations and rental contracts and sales of disputed land, depending on whether a member of a family acquires a parcel of land by donation or by rental of land from another family member. The non-recognition of the legitimacy of this donation or of the rental clauses by a member of the donor family is a source of conflict.

The roles played by older people in resolving conflicts over land management

According to the respondents, in the socio-political system of Djuablin, the mode of settlement of these conflicts depends on the customary and legislative systems in force.

The customary system

Both in other sectors of social life and in the context of land, the company Agni du Djuablin has a legal frame of reference on which its operations are based. This system gives rights to seniors in the sense that they are the ones who hold the decision-making power. In this customary system, ownership is collective. Only families can own the land. As this patriarch aptly put it:

"With us, the inheritance takes place in the large family, and it is the eldest sibling who we designate as heir. If he is not there, it is the eldest nephew of the same-mother sister that we choose as our heir. Not all of the deceased's sons, daughters and wives can inherit. And it is we Patriarchs who play this role" (NJ, 89 years old).

From this speech, it emerges that the roles of the elderly, according to the customary system, consist in the choice of the heirs of inheritance and patrimonial assets. They must, in this way, ensure that these goods, consisting mainly of land and plantations, effectively remain in the family. Any conflict arising from the use of the earth's space finds its frame of reference within families. Apart from them, the village authorities are involved.

The legislative system

In their attempt to resolve conflicts, they are relayed to the competent institutional actors, in case the village authorities feel limited.

"We are working together with the village authorities in resolving land disputes which are very recurrent in this border region in Ghana. The region is very fertile and attracts many migrants. The problem is that the people have their customs which have nothing to do with the legal and legal provisions with which we work. Perceptions of conflicts are different as to their origins and the ways and means of resolving them. But, we always end up getting along" (Group interview, Judicial authorities and Land and Cadastre Service).

Recourse to the legislative mechanism intervenes in matters of intra-community land conflict when the traditional procedure has failed or is contested by one of the parties. Here, it is made right to the legitimate beneficiaries in the event of succession to the property on the basis of presentation of the supporting documents (will, title of property, title of land). Its application in a cultural framework dominated by custom remains particularly difficult with the opportunistic behavior of certain land stakeholders. Often the decisions rendered by the authorities (prefect, judge) are contested by one or the other party who then finds the opportunity to take refuge in custom. This is how the customary authorities made up of elders are called upon again by the actors to settle disputes that have not yet been resolved.

Also, the settlement of land disputes by the elders obeys certain rules and procedures. According to respondents, settlement procedures are generally done amicably. Or, the parties do not spontaneously resort to modern legislation. The elders are the first to be seized because they know the history of the families' lands. However, their decisions are still not perceived as objective due to their tendency to favor certain actors, with reference to custom, to the detriment of others disqualified by custom but legitimized by civil law.

Likewise, before the customary authorities, disputes are settled amicably on the basis of socio-legal logics lying halfway between customary law and land regulations. This amalgamation of two systems obeys the concern of institutional actors to find a solution likely to ease the social tensions resulting from land conflicts. Actors therefore have a wide range of regulatory bodies that they can call upon. In addition, we note that recourse to a body obeys the objectives and interests pursued by these actors. Indeed, individuals who have more confidence in habits and customs bring the conflict to customary bodies when they are certain of winning their case, while those who claim modern law seize either the court or the prefecture. It is therefore not easy to determine or define a trajectory followed by individuals. This shows the complexity of land disputes. In the process of settling land disputes at the customary court, the college of notables designates certain notables to conduct an investigation which will consist in collecting testimonies and making visits to sites, the subject of litigation.

It is in light of the survey data that the customary court deliberates. In short, words and empirical observation form the basis of the settlement of land disputes by the elderly. Given that speech is the pledge or symbolic referent in any process of seeking a solution to conflicts in this society, it is important to dwell on the social status of speech activated by the elderly in order to establish their influence in the conflict resolution.

From the analysis of the results obtained, the following points will emerge which will be the subject of the discussion: ideological productions associated with land as sources of conflicts, contradictions between customary and modern legal systems as sources of conflicts, social prestige linked to the status of the elderly as a facilitator in the settlement of land disputes.

Ideological productions (beliefs, values, practices, standards) associated with land as sources of conflict

Ideology is defined as an intellectual and symbolic construction having a relationship with social behavior and the material life of social groups (Bourdon and Bourricaud, 2015). Ideology can designate what causes social actors to take as true normative propositions that are in essence and unprovable, and positive propositions which can be either unprovable or not demonstrated.

These authors believe that ideologies are constructions serving as a support for collective action and corresponding to specific issues; whether it is the strengthening of the cohesion of an institution, the legitimization of conduct and commitments or even the demonstration of merits.

About the land, in fact, Kobo says this: "Formerly perceived as a collective, inalienable good or a genitor deity, the land is above all, now an instrument, a source of enrichment or of affirmation of its ethnic identity (Kobo, 2003). Investigations in the villages of Djuablin show that the land for the Agni is a source of enrichment and above all an affirmation of their ethnic identity. As perceived in the imagination of Agni society, the earth is comparable to the "soul" and this allows it to exist socially. The earth is sacred because it is a gift from God. Each piece of land is owned by spirits, geniuses from whom men must ask permission before settling there. It is on her that the peoples settle. The land "is all of life, it is wealth, it is the heritage of the Agni." Therefore, we understand the close relationship of this people to the land. For populations, land constitutes a structuring element in the social reproduction of their identity. With regard to land disputes between nephews, the Agni company is a company with a matrilineal system. In this system, it is the eldest nephew who is allowed to inherit from his maternal uncle. This means that as long as the eldest is alive the younger must always wait. In addition, if it happens that while this younger brother is working with his uncle that elder is absent, when the uncle dies the application of inheritance standards often proves to be conflicting.

Because, these two situations will lead the cadet to categorically oppose this situation which he describes as unfair. According to respondents, conflicts between sons and nephews or uncles are the most frequent and violent. Also, in a society where women only have indirect access to land through their children, they play an important role in these conflicts. Very often forgotten after widowhood, the deceased's wife can count on her children to feed her before she enters into another marriage. They then activate the antagonism between various children and their uncle or nephew. For their part, the sisters of the deceased constitute the opposing party supporting the nephews. They are protectors of tradition when it is favorable to them. Rightly or wrongly, they support one side or the other. Based on this observation, the relationship between sons and nephews deteriorated. From there, these relationships are now conflicting in the sense that the sons no longer trust the nephews who refer to customary norms, while the sons refer to the law, that is to say to the administrative authorities. This divergence of views most often leads the parties to the conflict to resort to practices that are not recommended, that is to say magico-religious or occult practices in order to bend the adversary. In these conflicts which thus ensue between the nephews and the sons of the deceased, a solution is always found in the end for the conflicting parties, even if it may take years. Compromises emerge after discussion, but it is unfortunate that conflicts only subside after death on the side of the conflicting parties. In the sense that, in the way man cannot detach himself from his soul during his lifetime, in the same way the Agni cannot also detach himself from the earth at the risk of seeing their land disappear. This is why it cannot be permanently transferred to any individual who does not belong to the community. The land suddenly appears as the symbol of the cultural identity of this people for its social reproduction. Reproduction should therefore be the object of a lot of wisdom and finesse because the question of the land is very sensitive and the elders are, suddenly, the social category empowered to negotiate, to resolve conflicts because of experience acquired and mastery of the history of the people as well as land issues. This social representation of the land is a very important fact that has been taken into account in the socio-political organization.

Contradictions between customary and modern legal systems as sources of conflict

In the aftermath of independence, a famous political slogan according to which "the land belongs to those who developit" was launched by Félix Houphouët-Boigny. It is in this context and in this logic that a rural land code was voted on March 20, 1963. However, this text which ignored the habits and customs observed in most of our regions, further contributed to create tensions (Dagrou, 2005). It is therefore this legal vacuum, which had lasted too long, that Law No. 98-750 of 23 December 1998 establishing the Rural Land Code is supposed to fill. Its main objective is to bring order to this very sensitive area. It has the merit of specifying the rules and principles which will henceforth govern the occupation and exploitation of the land. It made it possible to circumscribe the latent or latent conflicts which undoubtedly found their source in the "legal vagueness", that is to say in the absence of specific texts applicable in the matter. In addition, there are many conflicts of interest in the succession systems in the Agni company. Customary societies are governed by two systems of succession and inheritance, the matrilineal system and the patrilineal system. The principles established at the level of these systems allow the transmission, without too many obstacles, of the family patrimony from one generation to another. Conflicts appear only between statutory beneficiaries of the inheritance. In matrilineal society, the first order of succession is the uterine brother, followed by the nephews (the sons of the mother's sister). This disposition is justified among all Akan whose system is matrilineal by the evocation of the story of Queen Abla Pokou. By passing the goods on to his brother or to a uterine nephew, one is sure that the good remains in the lineage and is managed by a relative (Koné and Kouamé, 2000). Thus, the modification of the sociological structure of the family, which is no longer totally governed by customary rules, renders inoperative the various legal registers on which potential heirs rely to ensure their right to inheritance and to the devolution of property prevails. Upon the death of a spouse, especially the husband, all latent or manifest conflicts of interest are revealed in all their contradictions. The conflict of legal systems (customary versus modern) has the consequences of weakening or completely destroying the unity of the family. Special interests take precedence over the need to preserve the cohesion of yesteryear. Succession disputes, which can take years to resolve, deprive children of the resources to meet their needs. It is the same when customary rules come to be imposed. Women and children are then stripped of everything without the heirs assuming the responsibilities imposed on them by custom: caring for widows and children. Thus, since the adoption of Law No. 64-379 of October 1964 relating to inheritance, another system of inheritance has come to be juxtaposed to the old one without ever having been able to replace it, nor to dominate it completely. In this context of dynamic social relations, having regard to political, social and cultural changes, the reference systems of the actors put on hold the beginnings of a rupture between the woman with her children and the in-laws. On this basis, customary law is intended to be the benchmark instrument in terms of the management and distribution of inheritance goods in the Djuablin. The preeminence of custom thus responds to a strategy of reproducing the village cultural identity, in a customary system losing its marks and landmarks. These contradictions between the legal systems (customary versus modern) are marked by land conflicts as to the latent or manifest interests of the competing actors. These land conflicts in Djuablin manifest themselves in fights, killings, witchcraft, curses, fetishism and poisoning. As for the actors, the conflicts are generally between the nephews and the sons of the deceased (ascendant), members of the same family, members of two families or two neighbors. With regard to the reasons mentioned, the customary mode of succession or inheritance, land management, contestation of land ownership, emerged from the speeches of the interviewees. In addition to these elements, there is confusion or ignorance of the land code, the application of the 1964 law on inheritance, the grabbing of land by the elders or the wealthy and the sale of family land. From the reasons mentioned by the respondents, two types of causes emerge: the causes linked to the logics of the actors and the structural causes, that is to say those independent of the actors. The causes linked to the logics of the actors concern the sale of family land, the contestation of land ownership and the grabbing of land by the elders or the well-to-do. These causes linked to the logics of the actors are apparently without any issue of conflict. They bring together two logics: individual logics or collective logics. In the imaginary Agni, the land belongs not to the individual but to the family. The deed of sale would then be nonsense and rightly a disregard of this provision, hence the obvious conflict. Moreover, the seizure of land by the elders deconstructs the ideology of the community to establish an individual logic of land appropriation that is based on non-collective properties (capital, cultural, symbolic, economic, etc). As for the structural causes, they refer to the customary mode of succession or inheritance, that is to say the application of the 1964 law on inheritance. It is then that contradictions appear in the articulation between the customary instances of conflict management. According to legal and administrative logic, in fact, succession and inheritance are passed on from father to son, while customary authorities establish the uterine route. Updating this contradiction due to the economic issues involved is reflected in conflicts of succession. The possibilities offered by this contradiction theoretically put the logics of the actors on the back burner and paradoxically contribute to opposing them. Therefore, two systems (customary and modern) that claim to be universal coexist while being mutually exclusive, and their reproduction only promotes conflicts within the Agni community. Thus the sometimes intergenerational social interactions around the land are marked by conflicts because due to urbanization, economic activities, such as agriculture and fishing no longer exist, and the land remains the only source of wealth for present and future generations. In other words, the social and economic issues as set out are sufficient to justify the climate of conflict maintained in the land arena. This duality of land ownership by the state and by the villagers carries the seeds of conflict situations in view of the decisive issues of land.

Social prestige linked to the status of the elderly as a facilitator in the settlement of land disputes

Social status is the place that a person occupies in the social structure. In Agni society, the place of elders is therefore culturally defined. If the statute emphasizes the legal and social situation, the role, for its part, emphasizes the tasks to be assumed and the expected behaviors. The role of elders therefore consists, on the whole, of behaviors that are legitimately expected of them. Their role in society is above all linked to their status as an old man, as a patriarch. In the socio-political system of Djuablin, the status of senior citizen reserves privileges to senior citizens. In this, the outward sign of this prestige is the renewed honor of the elders. All decision-making sessions, meetings in the village are chaired absolutely by the deans. They are the ones who solemnly open the sessions and the clauses. They are not subject to contributions and do not go to war. So, through the office of the dean, we celebrate the seizure of power by the old people. During the ceremony an emphasis is placed on age, proof that everything is done to celebrate old age (Dayoro and Kacou, 2010). In the field of land disputes, the elders are thus considered as people of experience, “who have lived, who have seen and who know…”. In this sense, therefore, they become a reference (Tanoh, 2014). Indeed, the land appears in Agni society as the symbol of the cultural identity of this people for its social reproduction. Reproduction should therefore be the subject of a great deal of wisdom and finesse. And, the question of the land being very sensitive, the elders are, suddenly, the social category empowered to negotiate, to resolve conflicts because of the experience acquired and the mastery of the history of the people as well as of the problems earthen. In view of the aforementioned, it emerges that, by virtue of their status, the elderly play important roles in the settlement of land disputes in the Djuablin region. The settlement of these land disputes is also related to the social prestige attached to their status as an elderly person, as a patriarch. And this privileged status of seniors can be seen on several levels. From a legal standpoint, for example, the oldest member has all the powers necessary to resolve disputes (Tanoh, 2014). Indeed, it represents the last legal authority of the village; hence his decision to dispossess a stakeholder of a piece of land and reassign it to another without appeal. Economically, the community is organizing itself to meet its needs so that it can easily perform its functions, including the settlement of land disputes. This is how in Djuablin, there are goods whose profits are mobilized to support it. Socially, under the palaver tree, the announcement of the arrival of the oldest member de facto commands members of the community to remain silent until he settles down. On the occasion of the assemblies, the elders have a special place reserved for them and they receive distinguished greetings from other social categories of the community due to their status. Regarding the management of village affairs such as land disputes, the dean has directly under his orders and services all generations of the village. In this way, the Agni society, through the oldest member, covers the elderly with laurel. Thus, the first palm that she offers to the elderly is the highest and honorary office of governor (dean of the village). Added to this are all the attributes of power, such as kaolin, cane and fly swatches which tend to worship the elderly since they refer to the religious field. Horizontally, the oldest member is the first of the Agni and vertically the extension of the ancestors, in that they hold the cultural heritage of the society. This relationship with the divinity constitutes a source of legitimization of the power of the elderly of Djuablin in the resolution of conflicts and in particular land disputes. This religious power makes the elderly intermediaries between members of society and ancestors. Thus, whether within the family, the generation and the village, its actions and opinions in relation to the settlement of these conflicts are decisive. All these social prestiges linked to their status, which are recognized in families and in other villages, make it easier for the elderly to settle land disputes in the Djuablin region.

The objective of this research was to analyze the social participation of the elderly in the settlement of land disputes in the Djuablin region. The qualitative approach was used and thanks to the sampling by reasoned choice, five (5) villages where land conflicts are rife on a recurring basis served as a geographical field for the research. Semi-structured individual and group interviews were conducted with 30 actors including 10 aged 60 or over (village chiefs and notables) and 20 other collective and institutional actors. The thematic analysis of the speeches of the interviewees highlighted the roles played by the elderly in terms of social participation. It is essentially a question of ensuring the safeguard of the family and community patrimonial and inheritance assets on which they are established as custodians. In this context, therefore, the choice of heirs is their responsibility, in strict compliance with customary law which governs the Agni du Djuablin company. They are thus responsible for settling all types of conflicts, in particular land disputes resulting from the procedure of succession, dispossession and reappropriation of land. The study also showed that the Agni of Djuablin variously represent the land as an inalienable good, soul, life, wealth and the reproduction of social identity. And, it is precisely around the earth that conflicts are structured. The conflicts observed in Djuablin are the consequence of the dualism of the systems and standards of reference of the actors in a field of competition where the various actors mobilize resources and capital according to their social positions. In such a situation, the participation of the elderly in the settlement of land disputes should be encouraged in Côte d'Ivoire; hence the social significance of the study. This social participation takes place with regard to the capital held by the elderly and the symbolic power recognized and legitimized by the social actors of the reference space. Beyond this social scope, the study is also intended to contribute to the reflection on the status and social roles of the elderly in Côte d'Ivoire. This is the basis for the scientific scope of the study. In perspective, this research could be deepened by broadening the geographic and social fields to all Agni regions of the Ivory Coast in order to better understand this social reality.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

The authors thank the customary authorities of the villages surveyed who guided them during this study by facilitating data collection and to the elderly who agreed to collaborate during the study. They also thank the officials of the land service and cadastre of the Ministry of Construction and Urbanization, the leaders of allochthonous and indigenous communities, the heads of women's associations, the heads of youth associations, the executives of the various villages and the judicial authorities of the Djuablin region.

REFERENCES

|

Adou K (2012). The intervention of kings and traditional leaders in the management of the crisis in Côte d'Ivoire, in institutional instability and human security, Gorée Institute 361 p.

|

|

|

|

Bagayoko N, Kone FR (2017). Traditional conflict management mechanisms in sub-Saharan Africa. Research Report-Franco-Paix n°2. Available at

View ' uploads ' 2017/06.

|

|

|

|

|

Boubacar H Bagayoko N, N'Diaye B, Kossi A (2010). The reform of security and justice systems in the Francophone space, International Organization of La Francophonie. Available at

View ' sites ' default ' files.

|

|

|

|

|

Bourdon R, Bourricaud F (2015). Critical Dictionary of Sociology. Edition Seuil, Paris. P 452. Available at

View book.

|

|

|

|

|

Dagrou T (2005). Understanding the rural land code of Côte d'Ivoire, Frat-Mat Editions, 2nd edition.

|

|

|

|

|

Dayoro ZAK (2008). Living conditions of pensioners in Côte d'Ivoire. Doctoral thesis in Sociology, Félix Houphouet-Boigny University of Abidjan Cocody, Côte d'Ivoire, unpublished.

|

|

|

|

|

Dayoro ZAK, Kacou FP (2010). Issues in the survival of eb-eb1 in Odjukru country. Institute of Ethno Sociology / University of Cocody / Laboratory of Economic Sociology and Anthropology of Symbolic Belongings (LAASSE). Revue Ivoirienne d'Anthropologie et de Sociologie. KASA BYA KASA, EDUCI 18:16-36.

|

|

|

|

|

Ebénézer CLK (2009). Social negotiations and participation of seniors in the settlement of land disputes. Master's thesis in Sociology, Institute of Ethno Sociology/Félix Houphouet-Boigny University of Abidjan Cocody, unpublished.

|

|

|

|

|

National Institute of Statistics (INS) (2014). Abridged results of the General Population and Housing Census 2014. Abidjan P 54.

|

|

|

|

|

Kacou FP (2013). Socio-anthropological approach to institutions for the integration of the elderly: the case of êbbeb among the adjukru, Unpublished Doctoral Thesis in Sociology, Institute of Ethno Sociology/Félix Houphouët Boigny University of Abidjan Cocody, unpublished.

|

|

|

|

|

Kobo PC (2003). Law No. 98-750 of December 23, 1998 on rural land in Côte d'Ivoire. Editions of CERAP, Nouvelles Editions Ivoiriennes, Abidjan. pp. 21-43.

|

|

|

|

|

Koné M, Kouamé N (2000). Socio-anthropology of the family in Africa, CERAP edition.

|

|

|

|

|

Lefrancois R (2007). Sociology of Aging, Chapter 4 in M. Arcand and R. Hébert, Precis Practice of Geriatrics, 3rd edition, Edisem and Maloine pp. 51-62.

|

|

|

|

|

Ossiri YF, Tanoh ACS, Dayoro ZAK (2017). Social representation of active retirement: the case of retirees affiliated to the international active retirement fund (FIDRA), EDUCI, Rev. ivory. anthropol. sociol. KASA BYA KASA, n ° 34.

|

|

|

|

|

Tanoh ACS (2014). Living conditions of the elderly among the Tchaman in Ivory Coast, Doctoral thesis in Sociology, Institute of Ethno Sociology / Felix Houphouet-Boigny University of Abidjan Cocody, unpublished.

|

|