Uncustomary and unofficial polyandry is very usual in Zimbabwe than is recorded and embraced by the majority of Zimbabweans. This study argues that nontraditional, unceremonious polyandry is frequent and appealing among some Zimbabweans despite the fact that it is condemned and rejected by traditional chiefs, diviners and the Christian churches. The study also contends that polyandry should be publicly practiced just like polygyny for it is not strange, not eerie and should be adopted and unreservedly experienced for it is not interdicted by both African Indigenous Religion (AIR) and Sub-Sahara African constitutions. The research results are that non- classical unorthodox polyandry in Zimbabwe is furtively experienced because polyandrists and their co- husbands are afraid of requital and popular vilification by the community at large, and by traditional chiefs, diviners and Christian churches in particular. There are some social and economic advantages which amass to polyandrists and their children, and also to the ‘co- husbands’ intentionally, at the same time sexually share a polyandrist. The conclusion is that polyandry should be openly embraced and consummated among Zimbabweans just as polygyny is plainly approved by them, and is openly acknowledged. Polyandry seems more likely to be a plan used by Zimbabwean women to realize their sovereignty and sexual independence.

When I was twelve years old, I was told that one of my aunts Manaka Mwoyosviba was a polyandrist, who was banished from the village by the sub-chief and, as I grew up I started hearing and reading stories in newspapers of polyandrists in Zimbabwe and, that kindled my interest in doing a research on polyandry in Zimbabwe…Author

The specific research setting of this study is Zimbabwe where unconventional polyandry is practiced. In those parts of the study where Africa and some African countries are mentioned, this study aims to show what is currently happening in Zimbabwe, previously happened and is happening in some African countries and in Africa in general but the focus country is Zimbabwe. This study also explores the reactions of polyandrists and their co-husbands to the vilification of polyandry by most Zimbabweans. Zimbabwean polyandrists are engaged in polyandry clandestinely for fear of reprisals by thecommunity, the traditional chiefs and the Christian churches.

Polyandry need not to be embraced by everybody in the society just as the various types of marriages, unions and sexual relationships like monogamy, polygyny, homosexuality and co-habitation are not unanimously approved in any society but are publicly practiced. Homosexuality is currently not publicly practiced in Zimbabwe. Just as monogamy, polygyny, homosexuality and co-habitation sexual romances are individual options; polyandry is also an individual choice.

Although polyandry is rare in Zimbabwe, it is not as rare as commonly believed, is found worldwide, and is most common in egalitarian societies. The study argue that non- classical informal polyandry is frequent and ever changing among Zimbabweans, and is not unnatural and hence should be embraced and openly consummated for it is not disallowed by both African Indigenous Religion (AIR) and the Sub- Sahara African national constitutions and laws. The study also contends that non- classical informal polyandry should be evaluated from a lively perspective. The study further debates that the commonly but covertly practiced form of polyandry in Zimbabwe is informal polyandry, and this is essentially ‘normal’, culturally speaking, although condemned by traditional chiefs, diviners, Islam and Christianity.

Zimbabweans who are involved in uncustomary, unconventional polyandrous experiences do them clandestinely for fear of the traditional chiefs, the Christian church and society at large, which give the impression of not to tolerate and view them as taboos. Women who openly involve in polyandrous behaviours are unjustifiably viewed as women of misplaced morals who are not fascinated in polyandrous romance but the financial and material gifts which they receive from their co-male sexual partners.

The author used literature review and face- to – face interviews to get information for this study. The research results are that informal polyandry is surreptitiously practiced by some women in Zimbabwe for among other things the satisfaction of their sexual appetite, the need to have children when one is married to an impotent man and for some economic benefits. The conclusion is that although clandestinely practiced for fear of chiefs and the Christian church, informal polyandry in Zimbabwe is a consequence of women liking their spousal rights, and sexual desires to be contented and satisfied, and hence women coax men into polyandry with the women practicing dominance and being in control in the relationships and marriages.

Problem

The predicaments under investigation are:

1. The seeming general belief among the majority of Zimbabweans that informal polyandry is non- existent in Zimbabwe, yet it exists, but is practiced stealthily and at times under cover of darkness because of fear of condemnation and punishment by the traditional chiefs, diviners and Christian churches.

2.The apprehensions, hostilities and animosities between the Zimbabwean informal polyandrists and the majority of Zimbabweans who are represented by traditional chiefs, diviners and Christian churches. The solution to the problem is to allow polyandry to be publicly and not surreptitiously practiced in Zimbabwe, and also not to condemned and denies it on cultural, religious and legal grounds. Polyandry should be accepted and practiced in Zimbabwe, just as polygyny is accepted and practiced.

Definitions of terms

The phrase ‘polyandry’ obtains from the Greek words poly and andros, connoting ‘many men’ (Starkweather, 2010). Jenni (1974) defined polyandry as the concurrent sexual union/bond between one female and co- husbands. Long established traditional polyandry is distinguished by community -wide recollection of a nuptial coupling as legal and co-habitation of co-husbands and wife (Starkweather and Hames, 2012).

Polyandry alludes to one woman simultaneously having more than one husband or male sexual partners both or all of them knowing, accepting and approving of the sexual relationship, while, polygyny is a case in which a man concurrently has more than one wife or female sexual partners and every one of them being aware of and accepting the sexual relationship.

The study agrees and uses the term informal polyandry as enunciated by Starkweather and Hames (2012) who argued that, “Non- classical informal polyandry does not involve marriage or co-residence in the same domicile but necessitates that multiple men were or are simultaneously engaged in sexual relationships with the same woman, and that all men in the relationship have socially institutionalized responsibilities to care for the woman and her children”.

Starkweather and Hames (2012) do not include marriage and co-residence in their definition of informal polyandry, but, the writer’s elucidation and use of the phrase ‘informal polyandry’ does differ with the way Starkweather and Hames (2012) defined and used it in that, this study includes marriage and co-residence in his explanation of informal polyandry, because some women in Zimbabwe were married and were involved in polyandry mainly for the sake of bearing children and, secondly for the sake of sexual satisfaction for their first husbands had erectile dysfunction. The study defines fraternal polyandry as when, brothers or kinsmen mutually and simultaneously have a sexual relationship with one woman and both or all the brothers know about the romance.

In this paper, the author, like Starkweather and Hames (2012), defines unconventional unofficial polyandry as when, two or more men deliberately, mutually and simultaneously have a sexual liaison with one woman and do not co-reside. Differing from Starkweather and Hames (2012), the study argues that Zimbabwean non –classical informal polyandry at times, does involve marriage and co-residence, and also does allow several men to simultaneously enjoy sexual admittance to the same woman, and are acknowledging duties to care for her and her children. Polyandry is regarded ‘conventional’ when one woman is married to numerous men concurrently. Classical formal polyandrous marriages are socially accepted and approved and all persons in the union have entitlements and duties towards the others, as well as any children that may come out of the marriage. At present, there is no formal polyandry in Zimbabwe for no Zimbabwean society accepts polyandrists.

Starkweather (2010) elucidated non-fraternal polyandry as “a union in which the men in it are not related in any way”. Fraternal polyandry can be defined as a marriage, in which two or more brothers are concurrently in a sexual union with the same wife, with the co-husbands having equitable sexual admittance to her. It is usually prevalent in egalitarian communities conspicuous of notable male deaths or male absenteeism and, is linked with partible fatherhood, the cultural trust that a child can have more than one father. Partible paternity is the notion that more than one father can donate genetic material to a child. The conviction in partible polyandry is that, all men who sleep with the child's mother may give biological materials to the child and share paternal duties. Partible fatherhood or apportioned paternity is virtually invariably managed by women and, is a cultural perception of paternity in a manner corresponding how a child is accepted to have more than one father; for instance, because of a philosophy that sees pregnancy as the aggregate consequence of manifold deeds of sexual intercourse (Starkweather, 2010). The raising of a child is apportioned to multiple fathers in a form of polyandric affinity to the mother, although this is not always the case.

Associated polyandry is defined as an amalgamation which consistently starts monogamously and concurrent supplementary sexual partners are integrated into the pre-existing synthesis afterwards (Starkweather, 2010). The word ‘associated’ involves any arrangement in which polyandry is a circumstantial and, optative conjugal techniques available to men who may or may not be relatives (Levine and Sangree, 1980). Associated polyandry is always different: the initial and chief co-husband invariably has the absolute dominance and possesses a leading and distinguished place in the marriage (Levine and Sangree, 1980, 398). In associated polyandry there is no co-habitation and teamwork on economic affairs, economic wealth are possessed individually-the division of economic business is uniquely obvious where the men are not relatives (Levine and Sangree, 1980). One of the greatest remarkable aspects of associated polyandry is its severe pliability -it’s ‘looseness’, for its arrangement allows and even emboldens substantial freedom of personal selection (Levine and Sangree, 1980, 398).

Levine and Sangree (1980) defined cicisbeism as “‘extramarital liaisons,’ and distinguish it from polyandry”. The word cicisbeism is derived from the Italian locution for lover, cicisbeo, and may be utilized to explain both male or female duplicity and adultery; nevertheless, it is customarily utilized all over the classical literature to explain female polyandrous deportment (Levine and Sangree, 1980). The cicisbeo was an accomplished, audacious lover of a married woman, who escorted her at communal entertainments, to church and other occasions and, had special sexual access to his mistress. Cicisbeism, is an approach of unenclosed and standardized infidelity sexual association always including co-habitation, differs strikingly with the confidentiality of extramarital relationships, even where the latter is secretively or confidentially accepted (Levine and Sangree, 1980).

Accounts of wife-lending and public sexual associations between women and their male lovers are comparatively frequent in the ethnographic writings, and seem to be related with an appreciable amount of sexual liberty for women (Levine and Sangree, 1980). Cicisbeism is a tradition which ostensibly is the masculine similarity of concubinage and performs as a practical and useful substitute to polyandry and, is not the precise equivalent of concubinage (Levine and Sangree, 1980). A cicisbean association is determined by the liberality and acceptance of the woman's husband, whereas a wife's authorization is rarely pertinent to her husband's association with a concubine (Levine and Sangree, 1980). In point of fact, it is obligatory for an association distinguished by affability and congeniality to triumph between husband and cicisbeo -absolutely in divergence to subsidiary marriage, where associations are typified by rituals and mutual constraints (Levine and Sangree, 1980). The study regards cicisbeism as a type of nontraditional unofficial polyandrous behavior.

Cenogamy is a condition of a society which allows wanton and licentious sexual intercourse among its affiliates (Dreger, 2013). What all these polyandrous romances have collectively is that, they can all be socially appreciated systems in which women may openly have numerous sexual mates simultaneously. Women in such organizations do not participate in “cenogamy ‘cheating’ by any stretch of the imagination, nor are the men being cuckolded” (Dreger, 2013). Black (2014) described polyamory as the practice of having multiple serial sexual relationships, with the total comprehension and agreement of all the people involved.

Social, cultural, religious and legal problems faced by polyandrists

Marriage in Africa includes the state (legal), culture (customs of the people) and the church (many marriages are officiated in the church in Africa).The Christian church, diviners and the traditional chiefs in Africa are totally against polyandry, culture accepts polyandry (see under subheading of this paper “Historically Polyandry was Experienced in some African Ethnic Groups” and the legal – the state is silent about polyandry). During the period of this study, the researcher did not hear or read or encounter any situation whereby, a polyandrist in Zimbabwe was brought to any court of law and tried, and fined or imprisoned. No court in Zimbabwe has tried a case involving polyandry. It is incomprehensible why the state would allow traditional chiefs to persecute polyandrists without condemning the chiefs for violating women’s rights to be polyandrists. There is no law in Zimbabwe condemning and rejecting polyandry. The Zimbabwean society, diviners, and the Christian church are very intolerant when it comes to polyandry yet they are very welcoming when it comes to polygyny.

Some Zimbabwean polyandrists are faced with the problem of having their polyandrous practices condemned and rejected by their communities, churches and traditional chiefs, yet other sexual unions like monogamy, polygyny and cohabitations are accepted and also same sex marriages are accepted in some African countries like South Africa. By condemning and rejecting all types of polyandry, Zimbabwean societies are denying women full authority over their own sexuality and freedom of choice- selecting a sexual romance they want to be publicly involved in. Chavunduka and Nyathi (2011) and Okwembah (2014) contended that, polyandry is very strange, unorthodox, eerie and abnormal, not acknowledged and indefensible in terms of African indigenous culture, religion or the law. Which law in Zimbabwe? There is no law in Zimbabwe which prohibits polyandry. Some Zimbabwean polyandrists and co-husbands who were involved in polyandry were fined large sums of money or asked to pay the fine in kind or were banished from their areas of residence by the traditional chiefs (Moyo, 2011), but polyandry is a form of sexual orientation just as monogamy, polygyny, cohabitations and same sex marriage are forms of sexual romances. As a result of the persecution, polyandry is practiced secretly in Zimbabwe.

Respondents, Chief Gogodzai Mundido and Diviner Tendeukai Cheukai concurred with each other and attested, “Polyandry is taboo in Zimbabwe and should not be practiced. It is a cultural misnomer which if allowed will result in natural calamities like unexplained human, animal and plant diseases and deaths, droughts, earth quakes and floods. If polyandry is allowed to be practiced in Zimbabwe, the ancestors will be angry and withhold blessings for this country. Polyandrists should be incarcerated in prison for not less than twenty years”. Some African Indigenous Churches for example the Johane Marange Apostolic Church (JMAC) heartily embrace polygyny but disdain polyandry. Interviewee, Kede Tasaranarwo, an eighty five year old member of the JMAC argued that polyandry is an anathema in the eyes of God and his church, no woman is allowed to have simultaneously more than one husband, only men are allowed to concurrently have more than one wife. Kede went further and attested, “Only polygyny and not polyandry is accepted in our Church because only polygyny was accepted in biblical times. The bible permits men to have more than one wife, but does not allow a woman to have more than one husband at the same time. The bible clearly states that polyandrists should be killed for it is abundantly stated both the Old Testament and the New Testament (Lev. 20:10, Deut. 22:22, Rom. 7:3)”.

Churches like the Anglican Church and the Roman Catholic Church have some male and female polygamous members but they do not accept polyandrists. Bishop Tinomuda Gwerevende of the Anglican Church said, “My Church does not allow polyandry because it is a taboo which is not even mentioned in the bible. We do not ordain women to be priests. This is in line with biblical teaching where St. Paul said, “I permit no woman to teach or to have authority over men; she is to keep silent” (1 Tim. 2:12). Polyandry gives women authority over men. This is disgusting in the eyes of God and the church”. I regard this as hypocrisy at its highest level. Gwerevende’s argument that in the Christian bible, both the Old Testament and New Testament, polygyny was accepted for example Jacob (Gen.29), and Solomon (1Kings 11:3) were polygamists, and in Pauls’ Letters (1Tim. 3:2, Titus1: 6) polygamy was accepted, but not polyandry, does not hold water as far as I am concerned, for polyandry is not even mentioned in the Christian Bible. The Christian bible like the constitutions of Sub- Saharan Africa are is silent about polyandry.

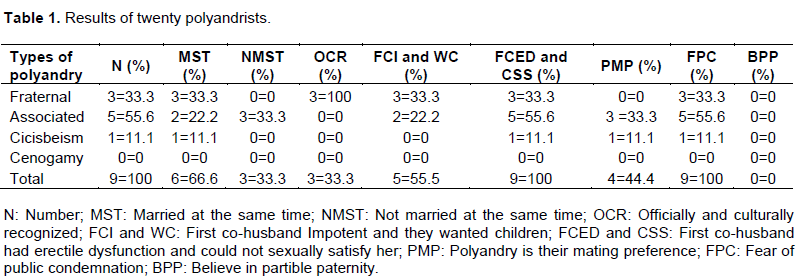

One hundred percent of the interviewees believe that monogamy, polygyny, co-habitation and same sex traditions are not the only path to sexual gratification, polyandrists and their co- husbands are pursuing their own satisfying sexual path which is polyandry (Table 1).

Again, 100% of the interviewed polyandrists were quite aware of the fact that polyandry was not approved of in their communities. However, they acknowledged that by practicing informal polyandry against the teaching of their communities they did not have any sense of guilt for all -100% of the study interviewees believed that monogamy, polygyny, cohabitations, same sex are not the only fulfilling types of sexual relationships.

Again, 100% of the polyandrists and their simultaneous male sexual partners said that they are aware of the fact that practicing polyandry is against the current cultural and religious teachings of traditional Zimbabweans, chiefs and the Zimbabwean Christian church. However, they acknowledged that by practicing polyandry against the teaching of the traditional Zimbabwean culture, religion and the Christian church, they do not have any sense of guilt except fear of the chiefs, diviners and Christian church leaders but not state law. They all knew that the constitution is silent on the question of polyandry. They are also afraid of practicing polyandry in public for fear of the public in general. My research results indicate that 100% of the co-husbands provided financial and material wealth to the polyandrist and her children whether the children are genetically his or not.

One hundred percent of the polyandrists interviewed feared public condemnation for practicing polyandry. Research findings were that 66.6% of the polyandrists who were involved in polyandry were married and 55.5% were involved in polyandry mainly for the sake of bearing children because their husbands or sexual partners were impotent and, secondly for the sake of sexual satisfaction for their first husbands had erectile dysfunction. Polyandry is not their mating preference because they are involved in polyandry in order to have babies and to satisfy their sexual desires for their husbands are impotent. The research results showed that for 44.4% of the interviewees polyandry is their mating preference. They enjoyed polyandrous practices just as some men enjoyed polygynous relationships. Married women who were involved in fraternal polyandry were 100% officially and culturally accepted and recognized, because traditionally it is accepted for a Zimbabwean male sibling or male kinsman to father children for his impotent brother. Traditional Zimbabweans accept fraternal polyandry for the sake of raising children for the impotent brother. This is the same as inheriting a widow for the sake of raising children for the deceased brother and materially and financially caring for the children left by the deceased brother.

Despite the fact that fraternal polyandry for the sake of raising children for the impotent brother is 100% accepted by traditional Zimbabweans and chiefs and condemned by Christians and Muslims, it is done in secret so as not to shame the impotent brother and, not to make the children born out of the polyandrous relationship not to know their biological father. The women (22, 22%) who opted for associated polyandry for the sake of raising children for their impotent husbands were condemned by the community because they raised children for their husbands by foreigners (vatorwa).

It is not accepted for a foreigner to father children for another man while his male close relatives are still alive. The unmarried polyandrists (33.3%) were involved in polyandry for sexual satisfaction and material and financial support for them and their children and, thus proving that unmarried women in Zimbabwe have more freedom to decide their mating preferences like polyandry. The unmarried polyandrists who engaged in polyandry for sexual gratification and material and financial support were condemned and rejected by their communities, diviners, chiefs and churches because they were perceived to be involved in polyandry for selfish reasons. All the polyandrists (100%) said that their first co- husbands had erectile dysfunction and, hence were sexually starved and opted for polyandry and they all feared public shame and condemnation and did not believe in partible paternity.

Kyara (2013) maintained that “polyandry among Africans is exceptional” but the study research results indicated that non- classical informal polyandry is common in Zimbabwe but is surreptitiously practiced. Four themes emerged from this research on Zimbabwean polyandrists: firstly the joy by women of being in a polyandrous sexual relationship -polyandry as their preferred mating predisposition; secondly impotence of the husbands who cannot sire children, thirdly erectile dysfunction of husbands who do not sexually satisfy their wives and lastly the polyandrists do not want to have a heart-break after a male sexual partner decides to terminate the relationship- they still have other co-husbands whom they fondly love. The findings indicated that the joy of being a polyandrist and a co- husband was the number one reason that made some Zimbabwean women get engaged in polyandrous behavours and why some men opt to be co- husbands. The impotence and erectile dysfunction of the husband were the number two reason that Zimbabwean men allowed for co-husbands in their marriages because this was necessary to protect the marriage rather than divorce.

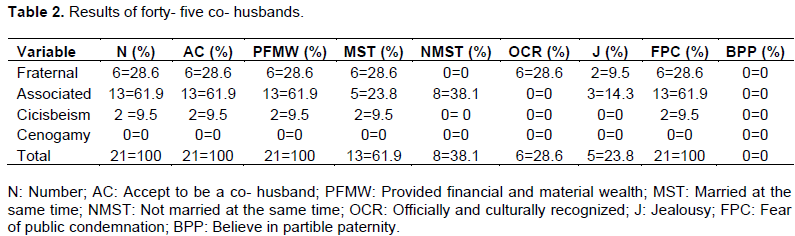

One hundred percent of the co-husbands knowingly and fondly accepted to be co- husbands, provided financial and material wealth to their sexually concurrently shared wife and feared public condemnation and shame by chiefs, churches and diviners for being a co- husband. The results also showed that 61.9% of the co-husbands were married, 38.1% were not married, 23.8 were jealousy and 0% believed in partible paternity. The 28.6% of men who were involved in fraternal polyandry did so because they wanted to raise children for their impotent brothers as per tradition.

Married men who were involved in associated polyandry were 23.8% and did so because they wanted to father children for their impotent friends and they were condemned by the community, chiefs, churches and diviners because they were not blood relatives of their friends. It is only kindred who are accepted by the community, chiefs and diviners to father children for their impotent male relatives.

The 38.1% unmarried men involved in associated polyandry and the 9.5 involved in cicisbeism did so because that was their sexual orientation. Unmarried men are more likely to be co-husbands than married men because unmarried men do not have a wife to control their sexual activities. Research results showed that associated co-husbands are more in number than fraternal co-husbands because associated co-husbands are preferred more by polyandrists, as compared to fraternal co-husbands who are only asked to father children within the family with their sibling’s wife or to satisfy her sexual needs. None of the co-husbands believed in partible paternity (Table 2).

Polyandrous practices have been one of Zimbabwean sexual phenomena

There is mainly one form of polyandry, informal polyandry in Zimbabwe, only fraternal informal polyandry is regarded essentially normal, culturally speaking, although condemned by Islam, Christianity and accepted by diviners and chiefs. The other types of polyandry like associated polyandry are condemned and rejected even by diviners and chiefs.

In the study point of view, the field of Anthropology has not treated this system with anything like the rigour and insight it requires; other social sciences and public health analyses are simply ignorant of it entirely. Formal polyandry, although desired by polyandrists and their concurrent male sexual partners, is falsely regarded as not existing in Zimbabwe by the majority of people, because of the disgust and abhorrence the society, churches, diviners and chiefs have towards polyandry in general.

Zimbabwean polyandrists and their simultaneous male sexual partners are totally in agreement with the writings of Frederick Engels on the beginning of the family. The most important work is Frederick Engels' Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, in which he relies on Karl Marx's notebooks on the American materialist anthropologist, Lewis Henry Morgan. Hence, there was considerable interest in these systems as the 19th century scholars discovered sex, the family, and kinship from Schoolcraft and Lewis Henry Morgan, through Charles Darwin and Sigmund Freud, but then there was almost no reasonable ethnography or knowledge.

Frederick Engels maintains that polyandry and polygyny were dominant during the time of primitive societies that is during the fruit and roots gathering, Stone Age and barbarian periods and monogamy as we know it today is a result of women’s oppression by men. Husbands were polygamous while at the same time their wives were polyandrous (Engels, 2008: 47), and that showed equality between husbands and wives. The public co-existence of both polygyny and polyandry meant that men and women were equal in every respect. Monogamy which is dominant today is the result of the oppression and exploitation of women by men (Brewer, 2008: 7). Engels and Marx challenged religion and science which regard women’s inferior status in today’s family as a result of God and natural differences (Brewer, 2008: 7). Both Karl Marx and Engels attested that the emergence of a class society which resulted in the emergence of monogamy as the dominant sexual practice in today’s families resulted in the oppression of women. For Angels and Marx the primitive society was equal in its social, political, economic and sexual relations (Brewer, 2008: 10). Free sexuality was the order of the day.

Morgan argued that during the primitive stage promiscuous sexual intercourse was rife within ethnic groups for every woman belonged equally to every man in the ethnic group and every man belonged equally to every woman in the ethnic group (Engels, 2008). “Group marriages in which whole groups of women and whole groups of men sexually belong to one another was common in primitive societies and that eliminated the whole concept of jealousy” (Engels, 2008). The fact that both polygyny and polyandry were acceptable in primitive societies eliminated feelings of jealousy from sexual relationships, co-husbands accepted each other without any sense of jealousy and the same applied to co-wives. Zimbabweans who resort to polyandry are simply going back to the roots, the sexual practice which was dominant in primitive societies before the oppression and exploitation of women by men. Polyandrists are asserting their equality with men as it was in the beginning of creation.

Some women like to be polyandrists just as some men like to be polygynyists. Starkweather and Hames (2012) attested, that “Neighbours and ‘co-husbands’ of polyandrists and those around them always know about the polyandrous behaviours of some women and their ‘co-husbands’ in their community, it is the denials of the polyandrists and their ‘co-husbands’ when exposed to the rest of society that perplexes me”. This equally applies to the Zimbabwean situation.

The study argues that, it is not true that polyandrists are not interested in romance but only in financial and material benefits from co- husbands. For me, this is not the case for some women who are involved in polyandrous practices and are professionals and business women who can financially and materially support themselves without the help of co- husbands. I debate that the polyandrists do not need financial and material help from their co- husbands, but they simply enjoy being in a polyandrous affinity just as some men enjoy being in polygynous experiences.

Mbiti (2004) maintained that polygyny is experienced, acknowledged and wide- spread in Africa and is a form of marriage in almost 15% of African families. The study observed that the majority of Zimbabweans do not accept sexual equality between men and women for men are publicly allowed to practice polygyny but women are not allowed to practice polyandry. The denial of women to be polyandrists is based on oppressive cultural, religious and legal grounds. Zimbabweans in political, economic and social forums theoretically advocate equality between men and women but in practice, they condemn polyandists. Men reject and condemn the practice of polyandry. The study attest that polyandry should be openly consummated and done among Zimbabweans just as polygyny is flagrantly acceptable to them and is openly experienced.

The study concur with Starkweather (2010) who debated that, “there are countless instances of women engaging in polyandrous practices, in which they maintain simultaneous sexual relationships with more than one man, but in which neither party has any rights or responsibilities towards the other”. Reasons that, although there may not be socially or culturally authorized liberties or duties between a woman and her co- husbands, there is more often than not still some kind of interchange between the parties that takes place. The study believe that, one example of this are the ‘social and economic capital for sex’ customs all over the world which fundamentally argue that male lovers proffer precious gifts like money, buying their sexual partners material goods like houses, vehicles, furniture, dresses and even make them to get very good high paying jobs in interchange for the females’ own highly-priced capital, sex.

The study observed that, this kind of model is recurrent among Zimbabweans and is paramount because women are accountable for the sources, therefore, her offerings of social and economic capital will undoubtedly be passed down to her children. The co- husbands can look for jobs for the woman’s children. “Therefore, even without formal social rules and regulations, the co-husbands in most societies are still providing important subsistence resources to the female and her offspring” (Starkweather, 2010).

The study agree with Hrdy (2000) debating several essential points focusing a great deal on female sexual freedom and polyandry. Hrdy (2000) is reported by Starkweather (2010) as reasoning that, “--- in very few societies do females have full autonomy, therefore, making informal polyandry far more common than the type of formal polyandry, which is practiced among the classical societies like Lowland South American, Tibet, Nepal and some parts of China and northern India” (Starkweather, 2010). This means that due to a dearth of sovereignty in marriage resolutions, along with a paucity of complete supremacy over her own sexuality, may leave a female with only concomitant approaches of managing which genes her children get, and how much the prospective fathers will invest in her and her offspring (Starkweather, 2010).

Thirty year old Memory Mlambo who practiced associated polyandry and lived in Zimta Section in Mutare contended that she was not sexually satisfied with one man and was concurrently living with two co-husbands Fungai Matandaudyi, who was 35 years old and Wesley Gora who was 30 years old (Dube, 2015). Mlambo maintained that she was not willing to jilt one of them for she equally loved both of them because one gave her gave her money, paid rent for the house and material wealth while the other one gave her attention and good quality sex (Dube, 2015). Mlambo dominated both co-husbands because they always did what she told them without arguing or fighting with her or between themselves. Matandaudyi and Gora were not jealousy of each other, respected and loved each other and gave each other time for sex with Mlambo (Dube, 2015).

According to Nyamayaro (2014), reporter with Nehanda Radio proclaimed that, a fifty- seven year old Zimbabwean African indigenous healer (n‘anga) Emma Chaleka, who practiced associated polyandry and lived in Gadzema Heights suburb in Chinhoyi, was living with two co-husbands Never Mudhenda and Sikabenga Pendasi and, intended to add two others for sexual gratification . Both Mudhenda and Pendasi traditionally married Emma by paying the bride price (roora) to their father- in- law Dick Chaleka. Emma Chaleka was reported as claiming that, her first husband Pendasi was failing to sexually satisfy her and, hence, she got Mudhenda as another co-husband with the agreement of Pendasi (Nyamayaro, 2014).

Emma was reported as having said “Pendasi is the one who brought Sikebenga here as he was failing to satisfy me sexually because of his illness and this was done in front of witnesses. I am prepared to have four co-husbands as long as they live peacefully respecting their duties. I can fight and beat all the men in this area, thus why they are afraid of reporting my polyandrous practices to the chief” (Nyamayaro, 2014). Chaleka is in full control of her co-husbands and her sexuality. The control of men by women is one of the reasons why diviners and chiefs and also the church as represented by interviewee Bishop Tinomuda Gwerevende condemns and rejects polyandry. Zimbabwe is a patriarchal society which hates women domination.

Moyo (2011) reported that Shupi Gladys Ngwenya who practiced associated polyandry and who lived in Gezi Line in Lupote Village, in Hwange, Zimbabwe, shocked her locals after marrying five co-husbands and divorced two of them. Ngwenya was called up by the sub-chief over the bizzare case of polyandry. “Ngwenya and the second co-husband were tried for polyandry at the sub-chief’s court and were found guilty and were fined one ox/cow and 10 000 Zimbabwean dollars. Despite being fined by the sub-chief, Ngwenya insisted that she wanted all three co-husbands, identified as an M. Dube (49 years old), who worked in Lupane; one Mackay and a Rodger, who were said to be both 46 years of age” (Moyo, 2011).

A thirty – eight year old woman Jack Chako who practiced associated polyandry and who resided at Bolon farm in Raffingora, Zimbabwe, was happily married to her two co- husbands Liford Chimoto, the senior husband and Michael Hwita, the junior husband who became the best friends after both of them married Chako (Staff Reporter, 2016). Chako opted for the second husband Hwita because the elderly senior husband, Chimoto, was not sexually satisfying her in bed and he (Chimoto), aware of the fact that he was not sexually satisfying Chako, allowed her to marry a second husband (Staff Reporter, 2016). Chako had two children within the polyandrous marriage whom she believed Hwita to be their biological father (Staff Reporter, 2016). The three slept on the same bed. The two husbands have different roles, Chimoto the elderly husband was weak both sexually and physically and, was assigned to fetch fire wood and cleaning the house while Hwita, who was younger and technically minded, was given the tasks of repairing broken goods in the house, cell phones, was a cobbler and brought some money for the up- keep of the family (Staff Reporter, 2016). Chako debated that she equally loved both co-husbands.

Sixty year old Tambudziko Svova who lived in Epworth, Harare, was impotent and could not biologically father children with his wife Ellen Svova. The two amicably discussed it and finally reached an agreement that Ellen Svova should marry a second husband, forty year old Kephas Takawira, so that he could sire children for Tambudziko Svova (Online Writer, 2016). Ellen practiced associated polyandry. In that polyandrous marriage, Tambudziko Svova’s duties were to support Ellen Svova financially and materially while Takawira’s responsibilities were to biologically sire children with Ellen Svova and, the two co-husbands lived happily together in the same house with Ellen Svosva and the children (Online Writer, 2016). Maria Vogel, a Zimbabwean woman from Bulawayo practiced associated polyandry. Vogel left Zimbabwe and lived in Barking, London, Britain with her co- husbands Paul Butzki and Peter Gruman who were both white Britons (Staff Reporter, March 5, 2013). Butzki and Gruman were friends and Vogel equally loved both of them and, there is no jealousy between the two co- husbands who also help with taking the children to and from school, help the children with school work and give them money and material gifts (Staff Reporter, March 5, 2013). Both children were sired by Butzki for Gruman came into the relationship after the birth of the children. The financial burdens of the family are shared equally among the three Vogel, Butzki and Gruman and that had increased joy and happiness in the family.

Some Zimbabwean men who at times numbered four men at a time were reported to simultaneously queue to have sexual intercourse with Shupikai Luwanda, a woman who lived in Chitungwiza together with her official boyfriend Byron Mujongondi (Staff Reporter, July 29, 2015). Luwanda practiced associated polyandry. The men are not jealousy of each other and they all give Luwanda some financial and material gifts. Okwembah (2013) reported that two Kenyan men Sylvester Mwendwa and Elijah Kimani signed before a lawyer an agreement to marry the same woman. Mlambo, Chaleka, Ngwenya and the Kenyan polyandrist became polyandrists because they did not get sexual satisfaction – lack of sexual satisfaction was the driving motive for them to be involved in polyandrous sexual activities.

In Zimbabwe, forced fraternal polyandrous relationships are sometimes discretely practiced for example the case of Muchaneta Masakura, who forced her daughter-in-law Modi Betisara, to have a surreptitious fraternal polyandrous relationship with her two sons. Masakura had two sons, Simbarashe Musharuko and Rangarirai Musharuko. Simbarashe Musharuko was married to Modi Betisara but Simbarashe was impotent. Masakura, was desperately in need of a grandchild but could not have one, and she then suspected that her son Simbarashe was impotent for he had failed to father a child with Betisara (Writer, 2016). Masakura asked Simbarashe’s younger sibling Rangarirai to be a second co-husband of Betisara so that Masakura could have a grandchild (Online Writer, 2016). Simbarashe agreed to share his wife with Rangariari so that Rangarirai could father a child for him but Betisara was not interested in the relationship (Online Writer, 2016).

In Zimbabwe, fraternal polyandrous relationships are always a closely guarded secret, which is only known by very close and elderly family members. Despite the veil of secrecy surrounding informal fraternal polyandrous relationships in Zimbabwe, polyandrists, co-husbands and neighbours of polyandrists and those around them are always aware of the polyandrous behaviours of some women and, their co-husbands in their community. Confidential informal fraternal sexual relationships for the sake of fathering children for the impotent brother are common and acceptable in Zimbabwe and are accepted by the chiefs, diviners and the community at large but are condemned and rejected by the church.

First co-husbands became co-husbands because they could not sexually satisfy their wives due to impotence or erectile dysfunctions or illness. Ngwenya was tried and found guilty of practicing polyandry because she was not involved in polyandry for the sake of biologically producing children as was the case with women like Besitara who were involved in fraternal polyandry for the sake of bearing children. Mlambo, Chaleka, Ngwenya and the Kenyan poliyandrist became associated polyanrists because that was their sexual orientation. They did not do it for the sake of bearing children. Some Zimbabwean women are involved in cicisbeism because that was their sexual orientation.

The study contends that most social scientists in Zimbabwe are under the premonition that polyandry is presently fictitious in Zimbabwe. The study alleges that polyandry is not peculiar within Zimbabweans for it has a cavernous Zimbabwean history. Most Zimbabweans view polyandry as a conundrum to be elucidated away, for them without any affirmation to confirm that polyandry was and is fictional among Zimbabweans. Polyandry is not imaginary in Zimbabwe, for fraternal polyandry for the sake of producing children for the impotent brother was secretly accepted so as not to shame the impotent brother. There was copulating multiplicity among Zimbabweans. The study insist that, the apprehensions about the nihility of polyandry among Zimbabweans are exactly at least in part to the fact that a huge percentage of Zimbabweans talking about polyandry are men, who believe that polyandry is unZimbabwean but polygyny is Zimbabwean. The study agrees with the study of Levine and Sangree (1980, 389) who reasoned that, “One more ingredient which makes Africans to have a conviction of the non- existence of polyandry among Africans may be the presumption that polyandry should like in polygyny where co-wives co-reside require co-residence of husbands, a belief which lies behind the unexceptional unwillingness to recognize the polyandrous nature of certain West African conjugal conventions”.

In modern polyandry in Zimbabwe, the polyandrist and the co- husbands do not co-reside and not form a single household. The majority of Zimbabwean co- husbands did not co-reside in a single household. There is a reasonably ubiquitous notion that polyandry does not make any sagacity from a Zimbabwean male's standpoint.

Historically polyandry was experienced in some African ethnic groups

The study talks about polyandry in other parts of Africa because, Zimbabwe is a part of Africa and it shares a lot of economic, social, political and cultural values with the rest of Africa. What happens in one country in Africa affects the whole of the African continent and this applies to polyandry as well. Also, for centuries, there has been movements of Africans from one region of Africa to another.

The migrating people carried with them their local culture which was, in most cases acculturated by their hosts. That culture was assimilated by the host ethnic group and it became an integrated part of the host’s culture. Integrating of the host’s culture happens with polyandry. The study wants to show that polyandry which is happening in Zimbabwe is not only limited to Zimbabwe but is found in the majority of African countries for they share some similar cultural aspects. Historically polyandry was experienced in some African ethnic groups and some polyandrists in Zimbabwe.

Dawson (1922 to 1932) maintained that in Burundi, Congo, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda both polygyny and polyandry were common. Alfred Claude Hollis debated that the Maasai of Tanzania were polyandrous as well as polygynous (Frazer, 2009). Lee (1972), argued that in 1964, there was one known case of polyandry among the Kung people who lived in the Kalahari Desert in Botswana. Lee (1972) said that by the time he conducted his study, there were more women than men in the ethnic group, with the women outnumbering men in every age group except for the adult group, which ranged in age from fifteen to fifty-nine.

Frazer (2009) attested that among the Buganda people of Uganda both the Queen Mother and the Queen Sister were allowed to practice polyandry, but not bearing children with the co-husbands for death was the penalty if they had off-springs. “Polyandry was common among the Bahuma people of Uganda”, according to Roscoe (1932), “due to the inability of a number of men to own enough cows to both pay the bride price and afterwards to supply the wife and family with milk” (Starkweather, 2010). “For the Canarians of the Canary Island, men were often away from home for extended periods of time and also there was a high mortality rate of men due to increasing contact with Europeans who spread many diseases to them” (Starkweather, 2010).

Polyandry was practiced on the island of Lancerote for Bontier and LeVerrier (1872) reported, “Most of (the Canarian women) have three husbands who wait upon them alternately by months, the husband that is to live with the wife the following month waits upon her and her other husband the whole of the month that the latter has her, and so each takes his turn” (Starkweather, 2010).

The Lele of the Kasai River in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) experienced unceremonious polyandrous romances (Tew, 1951). Polyandry was popular and was a celebrated romance for the Lele for it happened when the village gets a hohombe, or a village wife (Starkweather, 2010). The village wife was brought from a different village, either by coercion, mesmerized, taken as a refugee, or affianced from birth, and was respected with ‘much honour’ by the people in her new village (Tew, 1951). A village wife was espoused to all the adult males in the village, who might or might not already be mated. Being a village wife was very reputable for a woman, as was shown in her honeymoon time in which she did no hard work. Throughout that honeymoon period, the village wife slept with a different co- husband in her hut every two nights, and might have romances with any village men during the day (Tew, 1951).

Tew (1951) and Starkweather (2010) reported that “when the honeymoon period ended, the village wife was allotted a certain number of husbands, sometimes as many as five”. The village wife was expected to cook for all the co- husbands in the village and to have sexual intercourse with them. She might remove co- husbands from her family, and normally did so until she remained with just two or three.

According to Tew (1951), “though, it seemed that a village wife would forever be expected to be sexually available to all men in the village and any children she had would be considered children of the village, belonging to all men in the village” (Starkweather, 2010). That was a form of partible polyandry. Hollis (1905) reported unofficial polyandry among the Maasai people of Tanzania in the manifestation of women romancing with any man belonging to her husband’s age group.

In Zimbabwe, the idea of a village wife or a community wife as was the case among the Lele does not exist. In Zimbabwe, there is a notion of an ancestral wife (mukadzi wemudzimu). The whole idea of the ancestor’s wife is based on notional polyandry among traditional Zimbabweans. The ancestor’s wife was a woman who had her bride price paid by using cattle of a celibate diviner who was, in most cases, a rain-maker (jukwa). The wife is given to the diviner’s brother’s son who fathers children with the wife. Physically the wife is married to the brother’s son who makes her pregnant as his wife and bear children not for himself but for the celibate uncle. Spiritually, the wife is married to the celibate who has spiritual sexual intercourse with her. Traditionally Zimbabweans view the woman as an ascribed polyandrist who concurrently has two co-husbands- a spiritual one and a physical one.

Polyandry among the Irigwe people of the Jos Plateau in Nigeria took the form of what Sangree (1980) called ‘secondary marriages’. Secondary marriage was defined by Smith (1953), as “the marriage of a woman, during the lifetime of her first or primary husband, to one or more secondary husbands, which neither necessitated nor implied divorce or annulment of previous or temporarily co-existing marriages” (Starkweather, 2010). In the instance of the Northern Nigerians, a woman did not live with all her co-husbands concurrently, but was simultaneously wed to all of them, and affirmed her prerogative to have children with any of them (Levine and Sangree, 1980).

Muller (1980) differentiated primary marriage, as the initial conjugal of a girl, from secondary marriage, any of the girl’s succeeding marriages and gives additional friendship and solace for the proposition of the significance of affiliations for the Irigwe people. He went further and maintained, the fundamental philosophy of these Nigerian arrangements is to permit or even to compel a woman to be concurrently the wife of two or more husbands belonging to disparate categories (Starkweather, 2010).

The Irigwe of Nigeria are one typical illustration of a Northern Nigerian ethnic group that consummated polyandry in the configuration of paramount and ancillary marriages (Sangree, 1980). The parents of the couple normally organized the main marriage while the bride and groom-to-be were in their infancy. The progenitors were customarily either distant relatives, or the father’s friends (Sangree, 1980).Once consummated, the principal marriages naturally did not last longer than a few weeks, nor created any progeny. The secondary marriages were started by the couples themselves, were comparatively cheap, and almost consistently worked to bear children (Sangree, 1980). A woman was gifted to determine at any time which espousals she would like to respect and which she would not. She might also select which co-husband to live with at any given time and would normally gyrate between co-husbands on an impartially constant rationale (Starkweather, 2010).

The alternative position of community organizations was that of managing marriage and sexual affiliations, which uniquely used authorized multiple sexual amalgamations either in the configuration of totalitarian first and subsidiary marriage, or via the authorization of standardized cicisbeo associations jointly with marriage, to create a twofold position of cross-cutting bonds amidst contradicting kinds of vital and inconsequential race-related subdivisions (Sangree, 1980).

The Irigwe had agnate and kinship connections including co-husband romances. These links arose from their cultural marriage arrangement which ordained both first and subsequent marriages while interdicting marriage between individuals with the same affiliated sub-section parentage association, and prohibiting ancillary marriage between couples where the woman was already married to someone of the identical constituent (affiliation) as the man (Sangree, 1980). The system forbade constituent ‘brothers’ from becoming co-husbands, and also disallowed co-husbands from apportioning more than one wife (Sangree, 1980).

The study maintain that the Zimbabwean co-husbands who were involved in fraternal polyandry were kindred concurrently sharing the same woman for the sake of having children and, also debate that, the polyandrists who were married have second co-husbands who were brothers of their first co-husbands. This agrees with the Irigwe agnate and kinship connections which included co-husband romances.

Conventionally, the Irigwe did not recommend divorce; thus all marriages became an origin of incessant and more or less perpetual social relationships (Sangree, 1980). Men were not permitted to have subordinate wives. Principal marriages took place between couples whose progenitors were distant relative or friends (Sangree, 1980).

Sangree (1980) debated, such masculine ‘friends’ were non-kindred or far away family members who have concurred not to accept each other’s wives in subsidiary marriage, were hunting colleagues, and acted as contact men and go-betweens in commencing secondary marriage preludes with already married women. The study attest that like the Irigwe, the co-husbands among Zimbabwean polyandrists were involved in associated polyandry in which they were friends of the first husband and, they fathered children for their friend, and hence, Zimbabwean polyandrists were made pregnant by their husband’s friends in an associated polyandrous relationship.

In most cases like the Irigwe, the majority of children of associated Zimbabwean polyandrists were born from secondary marriages and not from primary marriages. Men were allowed to have more than one primary marriage and a woman was only permitted one primary marriage. Debating on polyandry among the Irigwe, Sangree (1980) argued that, the factual gain for the boy's next of kin from a first marriage was the kindred or friendship association, it assisted guarantee and fortify with the girl's father and family, and the supplemented reputation the boy's kindred obtained in the eyes of the society at large as a hard-working farmers whose sons and daughters were fit probabilities for secondary marriage. Sangree (1980) argued that the secondary wives would marry some other secondary husbands with the full comprehension of the primary husband, the same applies in Zimbabwe.

Similar to what happens in Zimbabwe, Sangree (1980), debated, a female offspring took some inventiveness and showed her devoted fondness by welcoming commitments to many suitors of whom her father endorsed; and people said a virtuous and faithful daughter would allure and welcome betrothal to a half dozen or more ancillary husbands throughout her early and middle teens. The polyandrist inhabited with the primary co-husband and paid constant sojourns to the secondary husbands with the full apprehension of the primary husband (Sangree, 1980). The polyandrists gave birth to children with secondary husbands (Sangree, 1980). Irigwe polyandry created a multiplicity of inter-kindred connections via matrifiliation that productive secondary marriage, established and co-husband interacted and brought ethnic inter-section tranquility and ethnic unanimity (Sangree, 1980).

Dynamism of Non- classical informal polyandrous practices in Zimbabwe

Polyandry in Zimbabwe is presently not ethnically and culturally approved by the chiefs, diviners and the church and the society at large but is an independent alternative. Polyandry is a panacea rapidly accepted by individual polyandrists who have a titillating impulse for simultaneously having sexual intercourse with a variety of men. It nevertheless, fulfills the principal elucidation of polyandrous romance: comparatively unshared mating among spouses and duty for the co- husbands to materially and financially support the woman’s progeny whether they are genetically theirs or not.

Like polygyny, monogamy, cohabitation and same sex sexual behaviours, polyandry has its own pros and cons. Just as there are ever increasing divorces in polygynous, monogamous and same- sex marriages, there are also divorces in polyandrous marriages. Starkweather (2010) argued that non- classical informal polyandry is no longer an ethnic tradition but a personal custom. Modern unofficial polyandry seems more likely to be a master plan utilized by women, and polyandrous romances interconnected to partible paternities are almost always directed by women. Despite the fact that partible fatherhood was welcomed among the Lele ethnic community for any children born by the village wife were regarded children of the village, belonging to all adult males in the village (Starkweather, 2010), the study interviewees Shorai Ruvimbo and Tsungirirai Zvinodaishe did not believe in partible paternity.

Interviewee Sunungurai Gapu agreed with Hrdy (2000), who argued that polyandry awards liberty to women. Polyandrists are in full control of their sexuality and are not controlled and oppressed by their co-husbands. This is affirmed by interviewee Gapu who said, “None of my three co-husbands controls and oppresses me. If he does, I immediately jilt him and look for another one. In fact, the co-husbands are afraid of abusing me because they know that I am not staved of men and I will jilt them if they do. They compete for my love.” Gapu again agrees with Hrdy (2000), as debating, “in very few societies do females have full autonomy, therefore, making non- classical informal polyandry far more common than classical formal polyandry, which was practiced among the classical societies”. Mwendwa argued that, his polyandrous partner had two children with another man and he hoped to have his own children with the woman, but the polyandrist would have to decide (Okwembah, 2014). Okwembah (2014) reported that, the Kenyan polyandrous woman was like the central referee for she could decide whether or not she wanted to be intimate with Mwendwa or Kimani on any day.

Modern unofficial polyandry is a female reproductive plan, used to guarantee a financing father for children if the primary father should die (Starkweather, 2010). The polyandrist and her children will still have a breadwinner who is encouraged to financially and materially support the children that may not genetically be his own (Starkweather and Hames, 2012).

Polyandry is leagued with lofty positions for women (Levine and Sangree, 1980). Interviewee Rongerai Panganayi attested that, modern informal polyandry is present among polyandrists whose social status is well above the norm, who have great freedom and who act with a level of composure and are not limited by males. Polyandrous experiences position women in powerful appointments in the family domain (Levine and Sangree, 1980). “The fact that the woman is the central figure, the pivot of the household, makes her the link, the guarantor of equality, between the associated co- husbands in polyandrous marriages” (Levine and Sangree, 1980).

Interviewee Mudzvova Zizi reported that in cases of impotence and erectile dysfunctional it is common and even acceptable for the polyandrist to begin the ventures which climaxed in the establishment of a polyandrous romance from a monogamous one. Polyandrists have abundant political and social freedom. Like Zimbabwean women, the Irigwe women energetically encouraged polyandry because it gave them more chances for boosting their social and family conditions (Levine and Sangree, 1980).

Interviewee Dzurai Gorwe attested, “I have three co-husbands who know each other very well. They all know that I am simultaneously in sexual relationships with them. I invite the one I want at any time to my house. If anyone comes to my house without my invitation I send him away. If he persists coming without my invitation, I break the sexual relationship with him and look for another one. I have told my co-husbands that they should not quarrel or fight over me. It is me who is in control of all the three co- husbands. I equally love them not because of the financial and material gifts which they give me but because I love to be in polyandrous relationships. My mating fondness is polyandry. I have a very good and well- paying job for I am a school teacher by profession. I can support and raise my two children without any material and financial help from any of my co-husbands”. Co-husbands are duty- bound to give their wife precise donations, but their amour had inconsequential implication past the sexual liaisons and the accouterment of lawfulness to children sired in the marriage. Okwembah 2014) contended that, the Kenyan polyandrist declined to select between the co-husbands for she was not prepared to discard any of them for she equally and dearly loved both of them. One of Ngwenya’s co-husbands committed suicide after a traditional sub- chief’s court attempted to terminate the polyandrous romance for he could not figure -out a life without Ngwenya as his sexually contemporaneously shared wife (Moyo, 2011).

Interviewee Magara Gumburai argued, “I married Nunurai Mhashu, and for two years I did not become pregnant. We consulted medical doctors and we were told that Mhashu is impotent for he has low sperm count. Mhashu asked me to be made pregnant by his younger sibling Zuvarashe for he wanted me to bear children with his relative. I talked to Zuvarashe about him fathering children with me and he agreed to make me pregnant and bear children for Mhashu. Mhashu was very pleased to find out that I was made pregnant by his brother Zuvarashe. Each time I want to be intimate with Zuvarashe, we do it discretely for we do not want Zuvarashe’s wife and the community to know about my polyandrous practices”. According to Magesa (1998), “every person had a moral obligation to marry and to contribute to the social reproduction of his kinship group. This most basic value, to beget or bear children, was instilled in all members of the society from early childhood onwards. Nobody was allowed to shirk this duty”. In Africa, the major purpose of marriage is to procreate and in occurrences the husband sense that he was impotent, he authorized his wife to have extra-marital sexual relations in order to mother children (Obuna, 1986).

Traditionally, Zimbabweans did not view marriage and sexual intercourse as for sexual gratification and pleasure but for procreation. Interviewee Mandirowa Mhute attested that she became a polyandrist because she discovered that one man cannot sexually satisfy her. Like Mlambo, Chaleka, Ngwenya and the Kenyan poliyandrist, she went into a polyandrous sexual relationship not for the sake of begetting children but for her own sexual satisfaction.

For Zimbabweans, marriage is a Godly and ancestral obligation that, under customary incidences, everyone is compelled or anticipated to accomplish. The bearing of children is the fundamental aspect of marriage, and no efforts are spared to guarantee that children are born in each marriage; apart from that, the couple is unsuccessful to become a family. Among traditional Zimbabweans, the genealogy at no time dies; only its members do. Mbiti (1969) maintained, “If the problem lies with the husband, then a close relative or a friend is asked or allowed to sleep with the wife in order that she may bear children for the family.” The consequences of failing to have children are great among Zimbabweans.

Traditionally, adults who died without bearing children did not have the bringing back home (kurova guva) ceremony a year after their burial. The kurova guva ritual makes a deceased person an ancestor who is constantly worshipped and offered prayers and sacrifices by the living members of his/her family for he/she is their protecting and blessing spirit. It is the desire of every traditional Zimbabwean adult to become an ancestor after his/her death. Traditional Zimbabweans who die without procreating do not become ancestors. The need for children makes impotent African men to ask their wives to be involved in either fraternal polyandry of associated polyandry.

Obuna (1986) maintained, “ In Nigeria, a man who died without procreating was not buried in the ground but was abandoned in the ‘evil forest’ where all those who die of such abominable and infectious diseases as leprosy and small pox were abandoned in the old days as food of vultures and other birds of prey. The reason was that since he had failed to fulfil his duties to the tribe through child- bearing, burying him in the belly of Mother Earth was viewed as an offence against the goddess of fertility, and thus bringing down her wrath on the whole community.” Fear of not becoming an ancestor and of being buried in the evil forest made impotent African men to sanction their wives to have some co- husbands who could make them pregnant. The children born belong to the primary co-husband and not to the secondary co- husbands.

Arranging for the wives of impotent husbands to have children by close kinsmen or friends was common among traditional Zimbabweans, and in some traditional communities in Zimbabwe. That type of polyandrous arrangement contented the connotation and justification of marriage for the people for procreation was highlighted in indigenous Zimbabwean marriages. The principal motivation of marriage among autochthonous Africans was to beget children.

Emenusiobi (2013) attested, “Life and transmission of life were esteemed values in indigenous African cultures, and to live for an adult indigenous African meant to be able to transmit life.” Marriage and begetting were therefore inextricable for the paramount goal of marriage was procreation. Breeding was geared at immortalizing an individual who procreated. In Zimbabwean indigenous culture, unfortunate was the man or woman who saw nobody to remember him/her as an ancestor offering ritual sacrifices and prayer or commemorate his or her name after physical death.

After death, a person who procreated was immortalized by his/her children and grandchildren as an ancestor. For indigenous Africans, “to lack someone who keeps the departed in their personal immortality was the worst misfortune and punishment that any person could suffer” (Mbiti,1970). Mbiti (1970) went further and said, “anyone who died without leaving behind a child or close relative to remember him or pour out libations for him was a very unfortunate person”. “A person who has no descendants in effect quenches the fire of life, and becomes forever dead since his line of physical continuation is blocked” (Mbiti, 1969). Obuna (1986) assert, “to die without procreating a child for an African, was to descend into oblivion- forgotten by both the living and the dead for children provided a link between the living and the dead members of a family, thus guaranteeing the continuation of life after death.”

Emenusiobi (2013) reasons “ only on the birth of a child did a woman become truly a kinsman in her husband’s family group and also only on the birth of a child was a man assured of the ‘immortality’ of a position in the genealogy of his lineage, or even his security or esteem among the important people of his community.” Obuna (1986) maintained that an indigenous African who died without fathering a child was considered a ‘waste’ – something literally thrown away.

For indigenous Zimbabweans to die without having a male child was as good as dying without a child for ancestry is viewed from a patriarchal perspective. Children are said to belong to the father and they get the totem (mutupo) and clan name (chidawo) from the father. Zimbabweans affirmed they can immortalize themselves in this world by begetting children, principally males.

According to Emenusiobi (2013), “a childless marriage as far as Africans are concerned, is indisputably a disaster.” Ndiokwere (1994) maintained, “an African man has to raise sons who will weep for him when he dies, sons who will maintain the family tree or lineage, so that it does not disappear from history”. Virility thus, was the paramount prerequisite in marriage. Male sterility and impotence were viewed and are still regarded as the most despicable state of affairs practicable for married couples. Shorter (2002) contends, “unfortunately, in the majority of cases, women were blamed when marriages were childless, although in almost half the cases of childlessness is due in fact to male sterility.”

Traditionally therefore, African marriage was more or less virility-oriented. Emenusiobi (2013) argues that “this fertility-oriented approach to marriage is very far from the person-oriented approach, that is, the concept of marriage as companionship which the ‘sexual and reproductive rights’ advocacy expounds, and on which western societies in general base its understanding of marriage – with or without children.” The need to be remembered after death as an ancestor makes impotent African men to ask their wives to opt for informal polyandry as the only way of having children who will pour libation on their graves when they die.

For men, unofficial polyandry tantamount a kind of indemnity for his children should he die, the other co-husbands will take care of his descendants after his death and, is utilized as a male reproductive plan in cases of impotency. When a male sexual consort is impotent, the benefits are that progenies are born for the co- husband who cannot biologically father children and the polyandrist has her romantic sexual needs met by the co-husbands. Mwendwa debated that “he had never been called a dad and her Kenyan polyandrous wife’s two children call him daddy and that gave him meaning and purpose in life” (Okwembah, 2014).

Khumalo’ associated polyandrous practices started monogamously and additional co-husbands were incorporated into the pre-existing marriage later on because of the need to procreate. Interviewee Muvhimi Gochanhembe said, “My wife of eleven years is in a polyandrous practice which I know and like very much for I cannot sexually satisfy her for I am suffering from erectile dysfunction. She goes out of our matrimonial home twice or three times a month to spend some time with her male sexual partners who are my friends whom I go with to the pub to drink beer together. My wife brings home some money and material goods from her sexual partners. Each time I meet her sexual partners, I thank them for the financial and material gifts”.

Gochanhembe’s situation was similar to that of Mudhenda who suffered from erectile dysfunction and could not sexually satisfy his wife Chaleka. Mudhenda brought the co-husband Pendasi into the home as he was failing to sexually satisfy Chaleka because of his illness. Neighbours witnessed Pendasi being officially made a co-husband of Chaleka (Nyamayaro, 2014). Chaleka said that she wanted another co-husband to satisfy her sexual needs for Mudhenda was sexually bewitched and was unable to maintain an erection after he cheated with a married woman (Nyamayaro, 2014). Chaleka maintained, “Whenever we wanted to have sex Mudhenda would feel weak and he decided to introduce me to Sikabenga as they share the same totem and our kitchen was changed to be the bedroom with Sikabenga” (Nyamayaro, 2014). For indigenous Zimbabweans, people of the same totem (mutupo) are kinsmen and hence Chaleka was involved in fraternal polyandry, just like the Irigwe ethnic group in Nigeria had cognate and affine ties including co-husband associations (Sangree, 1980).

Interviewee Maingireni Zongororo who had three co-husbands said, “AIR advocates polygyny among its members but I am an advocate of polyandry. I would appreciate it if AIR also allows polyandry. It is unfair for AIR to allow men to be polygynous and not allow women to publicly practice polyandry. What is sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander”. What is admissible for men is also legitimate for women (Ras, 2010, 113). This agrees with Engels and Marx who debated that during the primitive era, husbands were polygynous while their wives were polyandrous. Polyandry makes women control their sexuality as was seen in the cases of Mlambo, Chaleka and Ngwenya. Polygyny is justified by the majority of African men as guaranteeing the giving birth to many children so that the esteem and material wealth may be bequeathed on and, the family may become increased in number (Kunhiyop, 2008). For real gender equality, we must accept that what is good for men to do to women is just as good for women to do to men. Polygyny remains one of the large challenges confronting most women in Africa as it is nevertheless prevalent. According to Oduyoye (1992) is cited by Ian Ritchie (2001), “in her earlier work, made defences of traditional polygyny on the grounds that the traditional agricultural economy in Africa made it not only a viable but almost necessary institution, but she now makes a critical attack on it, making the point t

Informal polyandry in Zimbabwe is a result of women wanting their conjugal rights, and sexual cravings to be fulfilled and satisfied and hence women cajole men into polyandry with the women exercising authority and being in charge in the relationships and marriages.

Zimbabwean men go into polyandrous relationships and marriages mainly when they know that they are impotent and in some cases intensely in love with a woman who decides to be polyandrous. The men would not fathom leaving such a woman taken by other men and hence they opt for sexually sharing the woman with other men. Non- classical informal polyandry is much more prevalent in Zimbabwe than is written and accepted by Zimbabweans.

This research suggests that polyandry may have existed throughout Zimbabwean evolutionary history before the coming of colonialism. Unconventional polyandry is happening simply because women like to have polyandrous practices just as men like to have polygynous sexual unions.

This study established that non- traditional informal polyandry seems more likely to be a master plan utilized by Zimbabwean women to attain their social, economic and political autonomy and sexual freedom. This means that due to a lack of autonomy in marriage resolutions, along with a lack of unmitigated jurisdiction over her own sexuality may leave a female with only concomitant modus operandi like polyandry of regulating which genes her off-spring get and how much the probable co-husbands will materially and financially support her and her off -spring. The study also established that the practice of polyandry in Zimbabwe cannot be condemned and denied on cultural, religious and legal grounds.

The author has not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Agovi K (1989). Sharing Creativity: Group Performance of Nzema Ayabomo Maiden Songs, Literary Griot, 1(20):30-31.

|

|

|

|

Black D (2014). Is One Man not Enough to Satisfy You? Then Maybe you Should try Polyamory. Women24.

View

|

|

|

|

Bontier P, Le Verrier J (1872). Richard Henry Major The Canarian: Or, Book of the Conquest and Conversion of the Canarians in the Year 1402. Vol.1st ser. v.46. London: Printed for the Hakluyt Society.

View

|

|

|

|

Brewer P (2008). Introduction by Pat Brewer In Engels, Frederick. The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State Introduction by Pat Brewer. 23 Abercrombie St, Chippendale New South Wales, Australia: Resistance Books. pp. 7-23.

|

|

|

|

Dawson W (1932). The Frazer Lectures, 1922-1932. London: Macmillan & Co.

View

|

|

|

|

Dreger A (2013). When Taking Multiple Husbands Makes Sense. The Atlantic.

View

|

|

|

|

Dube L (2015). I am not Satisfied with One Man…Memory "Zhula" Parades her Two Boyfriends. Manica Post.

|

|

|

|

Emenusiobi RM (2013). Africa: A Continent of Love for Life and Children. Evangelsus-life Africa.

View

|

|

|

|

Engels F (2008). The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State Introduction by Pat Brewer. 23 Abercrombie St, Chippendale New South Wales, Australia: Resistance Books.

|

|

|

|

Fortes M (1969). Kingship and the Social Order: The Legacy of Lewis Henry Morgan. London & New York: Routledge.

|

|

|

|

Frazer J (2009). Totemism and Exogamy Volume 11. New York: Cosimo Inc. Gaza-Tshisa News Room. June 13, 2014. Blacks and White men compete to have Sex with One Prostitute.

View

|

|

|

|

Hollis AC (1905). The Maasai: Their Language and Folklore. Oxford: The Clarendon Press. Hrdy, Sarah B. 2000. The Optimal Number of Fathers: Evolution, Demography, and History in the Shaping of Female Mate Preferences. Annals of the New York Acad. Sci.907:75-96.

|

|

|

|

Jenni D (1974). Evolution of polyandry in birds. Zoologist 14(1):129-144.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Kirwen M (1987). The Missionary and the Diviner: Contending Theologies of Christian and African Religions. Maryknoll: Orbis Books.

|

|

|

|

Kramer K (2010). Cooperative breeding and its significance to the demographic success of humans. Annual Rev. Anthropol. 39:417-436.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Kunhiyop S (2008). African Christian Ethics. Nairobi: World Alive Publishers.

|

|

|

|

Kyara C (2013). New Evangelization and the Incidence of Polygamy. Hekima Review, Number 48.

|

|

|

|

Lee R (1972). Kung Spatial Organization: An Ecological and Historical Perspective. Hum. Ecol. 1(2):125-147.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Levine N, Sangree A (1980). Conclusion: Asian and African Systems of Polyandry. J. Comparative Family Stud. 11(3):385-410.

|

|

|

|

LeVine R (1962). A Witchcraft and Co-Wife Proximity in Southwestern Kenya. Ethnology. 1(1):39–45.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Mbiti J (2004). African Religions. Encyclopedia of Bioethics. Ed. Stephen Post. 3rd ed. Vol. 1. New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 84-89. Global Issues in Context.

|

|

|

|

Mbiti J (1975). Introduction to African Religion. London: Heinemann.

|

|

|

|

Mbiti J (1970). African Religions and Philosophy. New York: Anchor.

|

|

|

|

Mbiti J (1969). African Religions and Philosophy. London: Heinemann.

|

|

|

|