The incidence of street children around the world had raised concern about social order. Scholars have paid attention to socioeconomic and psychological implications ignoring the cultural dynamics that contribute to this development. This paper focuses on a category of street children in Akwa-Ibom state of Nigeria. They are the child-witches, thrown to the street due to witchcraft label masterminded by parents and pastors. Structural functionalist and Moral Panics theories were adopted. Focused group, participant observation, key informants, and in-depth interviews, as well as narrative analysis were employed. The paper revealed that while the phenomenon of street children in Akwa Ibom portrayed moral panic, Eket people, conceive behaviours that violate norms as a threat to social order, and consequently sanctioned. It recommends that parents should inculcate societal norms and values to their children. It concludes that the extremity of the sanction and the paradoxical presence of children on the street is an aberration of order.

Street children have gradually become common sights in most cities of the world. The term designates children who inhabit the street either as their permanent residence or means of livelihood. Most of their daily interactions and social relations occur there with little or no adult supervision or care. However, some are supervised by adults because some are sent by parents and guardians to work or sell wares to supplement income as Kaime-Atterhog (1996) and Aderinto and Okunola (1998) noted. This paper explores the ordeals of a category of street children that has been incriminated in Akwa Ibom state of Nigeria, owing to witchcraft label masterminded by the clergy who label children as witches, also pose as exorcists to whom parents’ recourse to. Consequently, they are sent out of their homes by their parents into the street to fend for themselves. Street living is precarious, even worst, is that the children under consideration are linked with witchcraft, which sets them at enmity with the community that perceives witchcraft as heinous. Thus, the children are abhorred, hounded, beaten, abused and violated by members of the community that consider them as undesirable. Abandonment of the street also exposes them to inclement weather conditions and criminal tendencies like stealing, alcoholism, drug abuse, child trafficking, prostitution and a host of other vices common among street children as scholars have observed (Ebigbo, 1996; Lugalla, 1995; Aderinto, 2007; Hassen and Mañus, 2018).

Statement of the problem

Studies on street children have featured in many scholarly works; they have explored various dimensions of the problems of street children, ranging from homeless and lack of privacy, to the socioeconomic, psychological and the health implications of street life. The phenomenon of street children has also been examined from diverse disciplinary backgrounds as sociology, psychology, economics and education (Oloko, 1989; Ebigbo, 1996; Osemwegie, 1998; Aderinto, 2007), but while they, undoubtedly investigated the menace of the street child, the anthropological content of their research is little, even less is the investigation of street children from the discipline of anthropology, which should actually be interested in the sub-culture that evolves from the street. Also, that with huge literature on witchcraft from anthropological studies, little attention has been paid to the involvement of children in the craft. Again, in criminology where literature is replete on juvenile delinquency, child witchcraft is rarely conceived as a form of deviancy. Therefore, this paper has become relevant as it bridges the above-mentioned gaps in the literature. More so, that it approaches the discourse from two disciplinary backgrounds -anthropology and criminology.

With an anthropological lens, it interrogates the phenomenon of street children from cultural dimension, stressing emic interpretation and response to behaviours that threatens communal norms and values that define collective conscience, which the children, by their involvement in witchcraft- a cultural reality- have defiled. From criminological angle, it views the response of the community as a moral panic, -a hysterical overreaction to juvenile delinquency and the labeling perpetuated by those Becker tagged moral entrepreneurs. This blend depicts interdisciplinary collaboration incorporating moral panic theory, traditionally used in criminology in anthropological research.

Objectives of the study

This paper focuses primarily on three objectives stated below:

1. To examine the behaviours of street children vis-à-vis communal norms, in order to uncover what in their conducts or behaviours make them elements disruptive of the social order.

2. To analyze the instance of Akwa Ibom street children from the standpoint of moral panic. The intent is to highlight the consequences of street living both to the children themselves and to the society at large.

3. Lastly, to explore other dynamics in the street child's malady that has hampered social order in the community.

Akwa-Ibom street children: a historical overview

Prior to the child witch saga, abandonment of children on the street had been rare in Akwa Ibom state. But, in the past decades, there has been a stereotypical image of children as witches and this has led to high incidence of street children in Akwa-Ibom state. This, as earlier stated, was made popular by the activities of some spiritual homes, particularly the prayer houses that have grown in response to desires for spiritual solutions to existential problems. The pervasive fear of witches has bred a deep sense of spiritual insecurity among the people. The fear stems from the community’s belief that witchcraft involves the invocation of and consort with the devil, and that witches possess supernatural powers that enable them to transform to animal familiars and perpetuate malevolent and evil acts. Thus, they pose legitimate threats to people. The fear was further heightened in The End of the Wicked, - a movie produced by Liberty films, which portrayed children as being capable of incarnating evil and death through their involvement in witchcraft, as indicted in the documentary titled “Saving the African Witch children”. Subsequently, some parents became apprehensive and suspicious of their children/wards and those who manifest deviant characters like lying, greed, stubbornness, or possessing unusual boldness or those considered as being destructive (attributes associated with witchcraft; Ukpabio, 2003:76) were regarded as witches, to be taken to churches where men of God can pray and drive out the evil. This was the social climate in which fears of child witches emerged in Akwa-Ibom, and was further intensified by the experiences encountered in the prayer houses through the activities of men of God, who capitalize on the charged social atmosphere to offer prophecies that easily indict children as witches and consequently, they were rejected and abandoned to the street.

The prevalence of street children is generally alarming. The question of why they are on the street prompted many studies, which indicate that the factors leading to children being on the street are multidimensional and vary from place to place as studies indicate. They were created by war and armed conflict (Loforte, 1994), poverty (Osemwegie, 1998), peer influence (Aderinto, 2007), unemployment (Onyebukeya, 2008), and a weakened family/communal ties (Akintunde, 2009), death or family disorganization (Hassen and Mañu 2018), and homelessness (Taylor and Walsh, 2018). Some studies have equally traced the emergence of this social malady to issues and problems of civilization (UNICEF, 1985). Although it has been conceived as a form of child abuse and neglect (Chineyemba, 2014), some view their visibility on the street as a cultural reality, noting that children work, not necessarily as a form of exploitation, but as part of the socialization process requisite for integration into the society (Ebigbo, 1996). Much as this assertion is credible, our view, particularly as it relates to Akwa Ibom street children is that they are victims of an unjust society grappling with an unstable economy that has produced avaricious elites that latch on impaired family relations to allocate to vulnerable children a position in the dislocation in the society that has hampered social order.

Perception and treatment of street children

Generally, street children are perceived as nuisance by members of the public, this perception stems from fear that they constitute a security threat as they can be easily lured into criminality criminal activities. More often, this fear stirs up hatred, hostility and violence against them. But the violence meted to them by some members of the community calls for caution. Cunha (1992) affirms this, noting that the act of violence against street children is not seen as an act of injustice, but is regarded as ‘favour’ done to society. Hassen and Mañus (2018) added that violence and abuse has become a daily reality for street children. This is particularly true for Akwa-Ibom street children who are berated, violated and molested by members of the public. Many ignore the fact that some of them are pushed to the street by circumstances beyond their control; as an escape route from torture, brutality and hostility of the family who want to exonerate themselves from the stigma and evil associated with witchcraft. Even, others consider the street a haven from the discrimination and segregation from the community owing to the label. The fact is that some children opt for the street as a last resort, when no other option is open to them. Anyuru (1996) argued that if children were given the necessities of life like food, clothing, protection, security, and access to good education, supportive and caring parents, only few would choose to live or work on the street. Indeed Beauchemin (1999) added that while street children have become a social problem, it is pertinent to note that they are not responsible for their dilemma. However, Akwa-Ibom street children are viewed differently, as witches, they are perceived as initiators of their own misfortune.

Theoretical framework

This paper anchored on structural functionalist and moral panic for theoretical explanations. Structural functionalists theorizing on how societies cohere noted that social order is prerequisites for the survival of the society. We

specifically examined Emile Durkheim (1947) and Parsons (1951) explanations of social order and Stanley Cohen's (1972), and other models of moral panic as theoretical basis for the explanation of this work.

Functionalists view social order as a regular and ordered pattern of relationships. They maintain that society is a complex system composed of many structures, with each structure functioning to maintain the whole. They believe that order and stability resulting from the cooperation of the various institutions or structures are indispensable for the maintenance and normal functioning of the society and its constituent parts. They opined that there are functional prerequisites that must be met by a system to function effectively, one of which they stated is social order.

Durkheim (1947) noted that social order is most important of all functional prerequisites. He observed the egoistic and selfish nature of humans; attributes that manifests as pride and self-seeking and could result in conflict and disruption of social relationships. To curtail these attributes and enhance peaceful co-existence, he coined collective conscience as that which summarizes common belief and sentiment as the basis of social order. He argued that the collective conscience restrains individuals from acting in terms contradictory to the requirement of the society. He believes that consensus on fundamental moral values are necessary for social solidarity because it binds individuals together to form an integrated unit.

Parsons (1951) on his part believes that commitment to common values bound by system of regulatory normative rule is the basis of social order in society. He pointed out that if members of society are committed to the same values, they will tend to share a common identity, which can provide the basis for unity and cooperation. He added that when values are institutionalized and behaviour is structured in terms of them, social equilibrium is attained.

Moral panic theory

Moral panic was first propounded by Stanley Cohen (1972), who explained moral panic as “a condition, episode, person or group of persons emerges to become defined as a threat to societal values and interests; its nature is presented in a stylized and stereotypical fashion by the mass media.” Thus, he believed that in an incident of moral panic, persons or groups perceived as posing threats to societal values and interest are identified by society’s guardians. He noted that often, the mass media and socially accredited experts -who includes editors, bishops, politicians and other ‘right-thinking’ people; voice their diagnoses and solutions on people they perceive as threats (Folk Devils), thus arousing social concern, anxiety and panic over the disruption of established value system vis-a-vis social order. Other scholars (Goode and Ben-Yehuda, 1994, Hall et al., 1978) have advanced other models of moral panic -interest group, grassroots and elite-engineered to further elucidate the concept.

The grass root model emphasizes that moral panics originate in a pre-existing, widespread public concern. In their views, the prevalence of these issues of public concern among some sectors of the society is what causes the moral panic. Moral panics must therefore be founded on a genuine public concern bothering on moral values which also can be amplified by the media.

Goode and Ben-Yehuda advanced the elite-engineered model, theirs was to further explain the where and why of moral panics. Like Cohen, they believe there are individuals in the society - political, economic, religious and other influential elites that instigate moral panics through their control of the major institutions of society. They argued that these elites deliberately and consciously create a moral panic to divert attention from other societal problems to protect their own interests, by creating fear and concern toward a behaviour that is exaggerated from an existing minor problem. They believe this is achieved through elites’ control of major social institutions like the media and other agents of social control- the police and the judiciary. They agree with Cohen that the media play key roles in instigating moral panics but maintain that the media amplifies rather than originate the panic.

The two theories fit into our inquiry. Functionalist’s emphasis on moral and common values that define the social order among Eket people, elucidates the response of the community to what they perceive as a threat to the norms and values (Offort) that define their collective existence. Moral panic on the other hand, pictures the situation of Eket street children that aptly fit into Cohen’s description of Folks Devils. The thrust of the other models of moral panic is equally useful as we shall analyze later. Based on the relevance of these theories to our discourse, they are adopted as the basis for the explanation of the reality of Akwa-Ibom street children.

Study location/site

Akwa Ibom is one of the thirty-six states in Nigeria. It is made up of 31 local government areas with the capital in Uyo. There are three major ethnic groups, namely, the Ibibio, Anang, and Oron. Eket is classified as one of the major Ibibio ethnic groups (Udo, 1983, Offiong, 1991, Ekong, 2001). Though some claim it is a distinct ethnic group from the Ibibio (Enodien 2008)

Eket people have their hometowns in Eket and Esit-Eket L.G.A.s, which in recent times have become a conurbation engulfing several villages made up of indigenous ethnic groups. The political structure of Eket comprises of three, embracing Afaha, Abighi and Atebi clans. The three are further divided into sub-clans of Okon, Afaha-Eket, Idung-Inan and Ekid-Odiong, among others. Eket is administered by a paramount ruler. The paramount ruler and clan heads constitute the administrative council. Also, there are village heads of the respective villages.

Eket people are predominantly Christians, as such, there are innumerable churches scattered around the city, particularly those noted for prophecy and proffering solution to misfortunes. This has led to increase in spiritual help seeking attitudes and the high patronage of churches believed to have the capacity to deal with the deep-seated sense of spiritual insecurity arising from the fear of the known and the unknown.

Ethical considerations

Ethical issues were considered for this study that utilizes human participants. It was necessary to protect the privacy and safety of the participants. To ensure this, the researcher expressed the aims of the research clearly to all participants, including the then paramount ruler of Eket, whose permission was sought before proceeding with the study in the community. Being a scholar himself, he understood the intent and willingly granted the permission. The village heads of the respective villages used were also informed. Similarly, at CRARN, permission and consent of the institution were sought and obtained from the president. Verbal consent of all informants, including the children was obtained before conducting the interviews. Of course, the willingness of the participants was crucial for establishing rapport and gaining the trust of the participants in the ethnographic study, especially as it relates to witchcraft, which is situated in context, as an issue of human security. Furthermore, in keeping with the promise of anonymity and confidentiality, a deliberate effort was made to avoid using names, but where it became necessary to mention names, pseudonyms were used to refer to informants. Also, the photographs were excluded even though a full album was collected in the course of the research work. Finally, the researcher exercised candor and magnanimity, especially at CRARN Centre, where gifts in cash and in kind were given to the children. Other participants were compensated for their lost time.

The research findings are outlined as follows:

1. Akwa Ibom street children are products of witchcraft labeling.

2. Offort (unwritten traditional injunction) is the basis for prescribing acceptable behaviours among Eket people.

3. Deviation from Offort is sanctioned in many ways, including witchcraft labeling.

4. Abandonment is one way the community sanctions violations of norms. Therefore, abandonment of children on the street is the community’s attempt to reinforce sanction deviancy, communal norms and reinstate social order.

5. Behaviours labeled are common in children; it is thus a form of moral panic.

6. There is more to the street children phenomenon in Akwa-Ibom state than deviation from norms.

While a lot of themes are central to this ethnographic study, this paper focused on two cardinal ones: Abandonment of children and the resulting street children phenomenon as a communal search for social order. The moral panic generated due to the paradoxical delusion of order owing to indiscreet abandonment of children on the street, conversely impairing the order it aimed to achieve. Other factors that are contributory to the street children phenomenon in Akwa-Ibom were also examined to ascertain the credence or otherwise of the purported search for social order. Beginning with the demographic characteristics of the respondents, the study proceeded to the findings and discussion of the intent and thrust of the research objectives.

Distribution of demographic characteristics of respondents

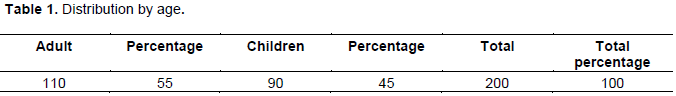

Several demographic characteristics of the respondents/informants were examined. Table 1 shows the age distribution of informants. The age distribution of the sample is broadly categorized into adults and children. A total of one hundred and ten (110) adults comprising 55% and ninety (90) children, comprising 45%, of the informants/respondents were used for the study. Age is a key variable in this analysis because age, particularly, that of the children is important in understanding/accounting for their behaviours, and as well, in evaluating the appropriateness of the sanction meted on them.

The children age ranged between 2 and 18 years old (statutory age). More emphasis was laid on the age of the children because their age is important in understanding/accounting for their behaviours, and as well, in evaluating the appropriateness of the sanction meted on them. Observation and interview with them revealed that most of the children that are abandoned on the street on account of the witchcraft label fall within this age bracket. This raised the concern, that children in their formative age are thrown out of the house, so they are denied the opportunity of acquiring the basic norms and values the family should inculcate in children, as the primary agent of socialization. Also, abandonment exposes them to hoodlums who prey on them. As children that mostly depend on adults for instructions and guidance they are prone to the influence of these people, who are ready to exploit them. More so, it is astonishing that children between two to five years old could be labeled as witches. At the CRARN Centre, it was observed that two of the children were two and three years old respectively and can hardly express themselves. It raises questions as to how they practice the craft. Little wonder, Tonga people of Zambia would suggest that children do not have the resources to obtain witchcraft nor the magic it requires to practice the craft (Colson, 2000).

Distribution by gender

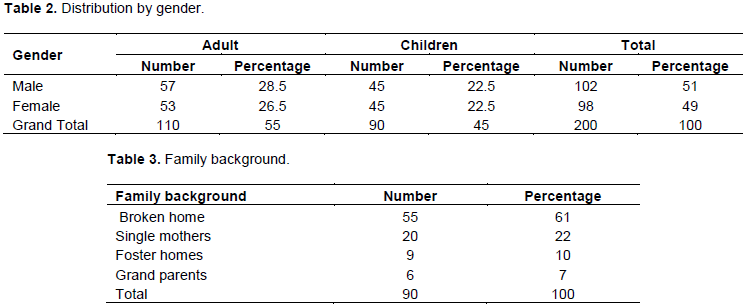

Gender is another demographic variable considered in this study. Though gender does not make much difference in the conception of witchcraft held by Eket/ Akwa Ibom people, as males as well as females, are believed to practice witchcraft. (Chineyemba, 2014, Ekong, 2001, Offiong 1991). However, it was necessary to examine how gender is reflected in the Akwa Ibom street children, and in the search for social order.

Table 2 shows the number and percentage of the informants by gender. The adult sample is 110, fifty- seven (57) males comprising 28.5% and fifty-three (53) females (26.5%) of the total adult sample were interviewed. The sex distribution for male adult is slightly higher than that of females because three out of the four key informants interviewed were males. This in part, reflects the social structure of the community, as two out the four key informants were chosen for the study because of the position they occupy in the community. Forty-five (45) boys (22.5%) and 45 girls (22.5%) of the children were interviewed. The sex distribution of the sample for the children is equal, although the number of boys at the Centre was slightly higher than the girls (108 males and 106 females), the difference is insignificant. It is, however, consistent with other studies on street children that record more boys than girls (Project Concern International, 2002; Save the Children 2009; Hassen and Mañus, 2018). The reason is obvious, socialization and gender role differentiation in a patrilinear society like Eket would account for constraining girls to the domestic domain while boys dominate the public space such as the street.

Table 3 shows the distribution of the informants according to their family background. Family background of Eket street children was important for the understanding of the reason for being sent out of the home. In view of this, the children were interview in the study, and some of their homes were visited as well to confirm/authentic their claims. First, it was discovered that most of them are from poverty-stricken families where survival is critical as some parents earn meager income as night watchmen (security guards), motorcycle riders, or are self-employed as petty traders and subsistence farmers where regular income is not guaranteed, and when it is earned, it is so low and hardly adequate to sustain the family. Some children stated that their parents are unemployed. It is, thus, difficult to generate income to cater for their families which in most cases is large, ranging, from 4 to 10 as the interview revealed. Some are even unemployed single mothers, lacking the financial capacity to care for their children. This financial hardship contributes to the street children phenomenon as counseling with a parent at the CRARN Centre revealed. Some of the parents blame their economic situation on witchcraft, on that ground; send their children out of the home to disavow their responsibility as parents.

The children’s position in the family varies, but a common factor is that the majority (61%) is from broken homes as shown in the Table 3, and most of them lived with stepparents (Dad or Mum). Twenty (20) of them, comprising (22%) was raised in families headed by single mothers, because, as was discovered during the interview, some were born out of wedlock; others have lost their fathers, or their parents had separated, and they are left in the custody of their mothers. Nine (10%) lived with foster parents; majority of whom are not related to them, while six (7%) lived with their grandparents. It is worthy of note that those that lived with grandparents also had other members of the extended family living with them. All of these have implications for street children as they become vulnerable to witchcraft accusations, especially that in Eket, witchcraft is blamed for every misfortune, including personal or systemic failures as it offers some people cogent rationale for exonerating themselves or the society of failures, by deflecting the blame on others.

Place of origin/residence.

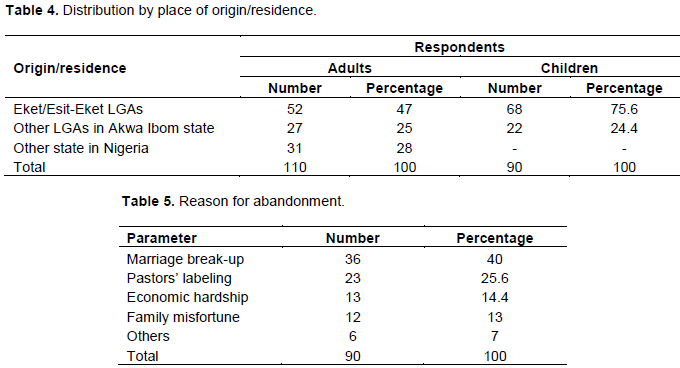

Another important variable considered in this study is the place or origin or residence of the informants, Basically, since the subject matter relates to communal norms, values, morals and belief system and responses based on them, we limited the informants to indigenes and residents of Akwa Ibom state. this is because people’s experiences can be interpreted from their cultural predilections. Also, that environment can influence or predispose people to accept certain beliefs, norms and value system hence we interrogated people from other states in Nigeria, but are resident in Eket, Akwa Ibom state.

Table 4 shows the distribution of the informants according to their place of origin or residence. Most informants (84.5%) are of Akwa-Ibom origin. 75.6% were from Eket and Esit-Eket Local Government Areas, while 24.4% are from other LGAs in Akwa-Ibom, state. Out of the 24.4%, from other LGAs, 17.4% resided in Eket/Esit-Eket with their parents/relatives before they were labeled; only 7% of them resided in other LGAs of the state before they were labeled, but were rehabilitated at the CRARN center as at the time of this study. Thirty-one informants (adults) comprising 28% of the sample are from other states of the federation but are resident in Eket as well. It is obvious from the data above that the dominant sample in this study is of Akwa-Ibom origin (84.5%). It is important to interrogate the place of origin, as people’s experiences can be interpreted from their cultural predilections. Also, that environment can influence or predispose people to accept certain beliefs, norms and value system.

Table 5 shows the reason the children advanced for their abandonment to the street. Lastly, the reason why the children were abandoned to the street was examined. The commonest reason given for being sent out of the home is witchcraft label. Ninety (100%) of the children interviewed confirmed they were labeled as witches (that was the criteria used for selecting them for the interview). Thirty- six children (40%) blamed their ordeals on father’s wife (marriage breakups). As earlier stated, family break-up is one of the reasons why children are thrown out to the streets to feed for themselves. Step-mothers’ engage witchcraft narratives to muster support, because it presents a convincing reason for sending out the children they perceive as threats or sources of conflict to their marital relationship. Some of the children confessed that they quarreled with their father’s wife, whom they said mistreat, starve or outrightly hate them. Twenty-three (25.6%) of the children blamed their street living on pastors, because as pointed out earlier, Akwa-Ibom street children are products of witchcraft labeling masterminded by the clergy. Interview with the children revealed that most of them were either labeled or have the label authenticated by the clergy before they were thrown out of the house. One stated that it was their pastor that advised her father to send her out, calming that her witchcraft is stubborn after a fruitless attempt at exorcism. A few (7%), of the children blamed their street living on other factors (such as family misfortunes-death, sickness, loss of job). Some said it was friends, some neighbours, others claimed uncles implicated them. 14.4% linked theirs to economic hardship (earlier highlighted). 68 out of 90 (75.5%) of the children said they were labeled in churches, the remaining 22 (24.5%) were indicted by other children that had been labeled previously. 52 (60.5%) had experienced exorcism by men of God, 6 (7%) with traditional healers and 25 (32.5%) said they were not taken anywhere for exorcism because of the monetary involvement. The longest time the children spent on the street was eight (8) years, as at the time of the interview; and for most of them, it ranged between three and five (3-5) years. 32% were on the street for less than one year before they were rescued and taken to CRARN for rehabilitation.

The norms and values of Eket people

Norms are the standard patterns of behaviour of a community. It is the basis of prescribing acceptable behavioural patterns to which members of a given community are expected to comply. They are the yardstick for measuring conformity, as well as standards. Norms are passed on to younger generations through the process of socialization. Eket community does not prescribe formal laws as the paramount ruler stated, rather, there is an ‘offort’ (unwritten traditional injunctions) which translates as socially approved norms and values and acts as a sort of collective conscience that guide behaviours. The royal father stated that no Eket person or anyone domicile in Eket can interfere or mutilate offort, which comprised of several norms, because the repercussion of such act is severe. He further opined that norms and roles can be gender and age biased, but noted that, generally, children of any age and gender are expected to perform those roles that will sustain the continuity of the group or family traditions. Obong-awan, the women leader of Okon community in Eket, speaking further on norms, stated that children are expected to be respectful, obedient and honest. They must embody sound character and, as image bearers, reflect and practice what the community upholds. She added that children must uphold communal norms, for to do otherwise is to bring shame to their families and the community at large. She specifically pointed out that children that are stubborn, idle, insolent, greedy, jealous and wicked or those that refuse to heed the advice or instruction of parents and, or, keep bad company signal the death of an image, both of individuals and the collective, because personal character and community image are of intricate complex web. Speaking of children’s roles, one parent said it includes running errands for their parents and helping with domestic chores. The village head of Uda Ikot-Afaha, said they carry out community assignments like sanitation, erecting village halls and lots more, depending on their age. They are indispensably positioned as utilitarian assets, on whom the moral and existential capacities of family and society rest.

Street children: as aberration of norms and order

As earlier stated, Akwa-Ibom street children differ from their counterparts in other places; theirs is a result of

witchcraft label, which is construed among Eket people in two forms, one, as a person that has confessed, or has been indicted by another witch, a traditional doctor/spiritualist or a pastor (Offiong 1991, Chineyemba, 2014), two in the form of deviation from norms and values. People whose behaviours diverge widely from expected norms are susceptible to witchcraft label as interview revealed. This notion is generally applicable irrespective of age, but since we are primarily concerned with children, those accused of witchcraft often demonstrate behavioural misconducts like stubbornness, insolent, greed and disobedience that parents find incomprehensible. Whereas, societal expectation is that children should comply with the directives of their parents or guardians, as the assumptions is that whatever directives parents give is in the best interest of the child. However, in a changing dispensation informed by increase in information technology and access to the media, this notion of parent-child relations is willingly challenged or completely broken away from by the children (Davis, 1980). This departure defies and challenges parental authority and breed intense intergenerational conflict between parents and children that is often interpreted as one of insolence and insubordination. When children are insolent, unruly or blatantly flout and disregard the authority of their parents, parents find such acts disturbing, not only because it contravenes moral codes, but also, because it challenges the control of authority and existing order in the family, and glaringly portrays parents/family negatively. When children constantly engage in acts that contravene collective conscience, they signal the weakness of the family and the community as having lost their control over them. Children that breach communal norms in this regard, stand the risk of character scrutiny as the clan head asserted, and because blame must be ascribed to someone in times of mishap, such children become ready scapegoats on whom evil is attributed at times of family crisis. This agrees with the moral panic theory, that society identifies scapegoats, characterized as a suitable screen to whom the ills of the society is predicted and attributed (Hunt 1997). Suffice to state, however, that the children often targeted tend to be those that are already in vulnerable positions either because of family misfortune (death, sickness, unemployment, poverty) or vulnerable due to the crisis that impair family relations (marriage breakups and remarriages, step father/mother imbroglio). This goes to affirm Becker’s (1963) assertion, that labeling is a matter of social definition. The badness of an act stems from the way people define it, in which situation and with respect to which people. This particularly holds true for some of the children who are perceived as sources of drain on family resources or those that find themselves at the heart of family dynamics in times of crisis, such children as we observed, were easily accused of witchcraft. Thus, the already vulnerable positions of the children were exploited to the extreme through accusations of witchcraft, which, in any case, represent an attempt to resolve the crisis within the family (Ranger 1991; Olsen, 2002).

In pursuit of this, parents are left with two alternatives: One, to seek a solution from pastors with regards to difficult children, who represent a problem for them, howbeit, at a very high cost of exorcism charged by pastors (buttressing elites engineered model). The second option open to parents is to accept the label, reject and abandon the child on the street, because abandonment is, as the paramount ruler of Eket stated in his book, one of the ways violators of the norms are sanctioned. But this sanction has grievous implications, especially for the children. As Becker (1974) rightly observed, such treatments deny them the ordinary means of carrying on the routines of everyday life open to most people, and because of this, the labeled must develop illegitimate route. On this backdrop, labeled children in Akwa-Ibom sought an alternative route to life. Street living became the available option open to them, and because street life is perilous, they encounter great difficulties there. One, street children are doubly stigmatized. Witchcraft and street child (ren) are disparaging labels that are despicable and deprecatory on the image, reputation and personality of the children. Both labels create social distance difficult to cope with. Social distance correlates with spatial distance and social exclusion which invariably limit their societal acceptance. This has significant implications for self-conceptualization, particularly in that it raises the perception to undesirable factors in self-construction. As Haralambus (2004) has observed, the individual self-concept is largely derived from the responses of others, and to this end, the labeled tend to evaluate them and act in the light of the responses of others. The danger inherent in this is that it may set them on what Becker (1974) has termed a “deviant career”. That is, continuing in the act for which they were labeled. Witchcraft label invites expulsion and create outsiders whose chances in life are reduced. Generally, as we observed, members of the community distance themselves from the children, associating them with evil. For instance, street children in Eket were denied admission in public schools. Some that were sent to the apprenticeship programme (spray painting) by the NGOs that support them (CRARN and Stepping Stone), were expelled and rejected because the landlord and co-tenants of their master insisted, they should be thrown out. They were thus, denied the opportunity of acquiring skills desired for self-reliance and economic empowerment necessary for sustenance and meaningful existence. Street children were in this sense, stigmatized, marginalized and discriminated against. They became alienated and unwanted as social outcasts, and in their attempt to create a world of their own, with its meanings and realities, they often engage in discrepant acts that further damage their identity, mar relationships and disrupt the social order.

Two, street children are obtrusive because street living negates societal expectation that the home, rather than the street is where sane people live. The children revealed that street life is hazardous and uncertain, because they had to fend for themselves. To do this, they engage in menial jobs like sweeping market stalls, carrying luggage for people and washing of plates in restaurants, to make a living. But, these jobs only last if the label is not known to their employers. Once the label is known, they were displaced, and they resort to illegitimate means of meeting basic needs. Some of them owned up to pilfering, burgling peoples’ shops at night, engaging in commercial sex practices to earn a living. Some made the market, their permanent residence, scavenging from the gutter and dust bins to eat. Such is the fate of Eket street children. They live in socially precarious and unpredictable circumstances where survival is dependent on chance. Stealing was inevitably employed by the children as a survival strategy. Many of them confirmed they pilfered, stole from peoples’ shops, and some had served as spies for armed robbers. Another admitted they fight, smoke marijuana and cannabis and even sell it to get money. These acts contravene collective norms and further affirm the community’s assertion about them as amoral. And because such practices were carried out within public space, which is collectively shared with other members of the community, involved in the social production and construction of the space, they are mistreated by members of the public. Most of them bear the scars of rejection inflicted on them because they occupy spaces which were not intended for them. They were constantly molested by hoodlums and preyed upon by child traffickers, who capitalized on their predicament to gain advantage. In return, they have become violent and hardened in their bid to defend themselves against the incessant hostilities and assaults they suffer from members of the public. Thus, the children-society relations have constituted new risks and uncertainties and social order is further threatened.

Street children and moral panic

Scholars have considered moral panic as a disproportionate overreaction to a person, situation or series of events (Hall et al., 1978; Garland, 2008). Similarly, Akwa-Ibom children witchcraft and the resulting street children phenomenon vividly fit into the description of a moral panic. Beginning with Cohen’s model, Eket street children simply fit into the description of scapegoats. The resident staff at CRARN, who also served as one of the key informants, observed that the behavioural incongruities the children depict is common among other children, but noted with regret, that ‘these ones’ are singled out for bad image characterization. This further affirms Tannenbaum (1938) assertion, that delinquent act, which children/adolescents engage in as adventure and fun could be misinterpreted, and when it persists, it is redefined as evil. The evil image portrayed them as children to whom members of the community’s fear and anxieties are cast. Eket street children project sentiments of fear and ambivalence because it is believed that as witches, they possess powers that can harm their victims. Witchcraft is sandwiched in fear narrative, the fear about the safety of lives, as witchcraft is implicated in what is malevolent and causes harm and could outrightly destroy or exterminate human lives. It is also founded on the threat it poses to the moral order and collective existence of the community through the selfish interest witchcraft promotes over collective good. Fear, as scholars have observed, play an important part in creating moral panic, because it promotes a sense of disorder and anxiety that things are out of control. This raises a sense of urgency that something must be done, exorcism is resorted to, but when it fails, abandonment of the children on the street becomes inevitable. The irony of the panic is that, abandonment of children on the street, poses greater threat, as street living disposes them to criminal tendencies and security threat that further threaten the social order.

Furthermore, witchcraft, the underlining reason for Akwa Ibom street children, exited historically and in contemporary times, and has been an issue of public concern as the grass-root model of moral panic poised. Several studies (Offiong, 1991; Ekong, 2001; Chineyemba, 2014; Umukoro, 2016; Iwenwanne, 2018), have documented several witch-hunts, concerns and widespread public outrages raised over witchcraft in the state. The child witch episode is only one of the numerous that has drawn public attention and concern.

Elite engineered model poised that moral panics are instigated by elites, who use it as a smoke screen to divert attention from their hidden motives. Similarly, Akwa-Ibom children witchcraft and the subsequent street children malady are masterminded by the clergy, people that are socially accredited as moral entrepreneurs in the society. They initiate the panic for their egoistic and selfish interest, because it allots to them social visibility and economic capital that accrue from exorcism (Chineyemba, 2017; Fakoya, 2009). Our observation in the churches visited, revealed that the clergy devise various means of extorting money from their members/clients. They raise funds, collect offerings and seed faiths and even impose assignments, all in the bid to make money. Exorcism for them has become money spinner at the expense of vulnerable children. A parent confirmed that she spent huge amounts of money on exorcism, and when she could no longer afford it, she had to send the child out to the street.

Like most episodes of moral panics, Akwa-Ibom street children (child witches) was media driven. The film titled ‘the end of the wicked’, produced by Liberty films, was alleged by the media to have raised public consciousness about the existence of children in witchcraft. Coupled with the charged social climate already tensed with spiritual uncertainties and fears, the awareness created by the movie stirred up agitation about the existence/ involvement of children in witchcraft. Since the media is the court of public opinion, it largely influences, forms and inform public opinion on issues of public concern. Thus, through the movie, the public adopted the position of elite on the capacity of children to practice the craft. Also, the documentary on channel C4 titled “Saving the African Witch Children”, sponsored by Stepping-Stone; a UK based Non-Governmental Organization (NGO), that went viral on the issue of children witchcraft, raised mass hysteria about the cruelty and mistreatment of Akwa Ibom street children. Since then, there has been several articles and posts on the internet on Akwa Ibom children witchcraft. It is thus initiated and sustained by the media.

Beyond the propositions of moral panic theorists, Garland (2008) identified the features of moral panic to include; concern, hostility, consensus, disproportionality and volatility. Akwa-Ibom street children narrative incorporates all of these. Thus, it can rightly be described as a moral panic, because of the anxiety portrayed over what constitutes a threat to fundamental systemic values necessary for effective functioning of the community. The concept of morality, however, suggests a dichotomy between right and wrong or good and evil as Wright (2015) asserts. The moral dimension necessitates the need to explore further, what in the conception of Eket people, constitutes social order.

Street children and the search for social order

Situating Akwa Ibom street children in the sphere of moral panics alone, conjures the notion of inappropriateness and overreaction to children’s deviant behaviours (Garland, 2008; Rohloff and Wright, 2010; Falkof, 2018). Because to the outsider, the invasion of the streets by children could appear to mirror the failure of the family and the community that have objurgated their roles as the bedrock of children’s welfare and protection, but there is the emic interpretation of the phenomenon. Social order like functionalists observed, is requisite for the survival of any group or society. It therefore follows, that for any society to cohere, efforts must be made to ensure compliance to what defines collective existence and binds the society together to sustain the indivisibility and peaceful co-existence of members of that society. As the Paramount ruler of Eket stated, collective conscience (offort) governs the behaviour of members of Eket community. Deviations from them are sanctioned because it violates the cultural ethos and threatens social order of the society. Individuals whose behaviours diverge widely from social norms are sanctioned either through moral coercion like satirical statements and ridicule, verbal abuse, or more severe sanctions like an accusation of witchcraft affirming (Offiong 1991; Noah, 1993). The village head of Ekid-Odiong, further added that violators of communal norms could also be fined or ex-communicated. The paramount ruler, however, noted that the sanction is relative to the nature of the offense one commits. That in odious cases, like murder or an accusation of witchcraft, drastic measures is deployed. He recalled that such violators in the past were abandoned to the evil forest (Akai Edoho). This presupposes that abandonment as is the case of street children, has been one of the ways violators are sanctioned in Eket. This is presumable because, as Ekong (2001) and Offiong (1991) stated, being labeled a witch, Ibibio conceive of such individual as posing serious threat to life and to the cooperate existence of the community. It is worthy of note, however, that the Ibibio are not alone in this, Hunter (1936) equally observed among the Ponder of South Africa, that any who violate norms or whose character diverge widely from societal expectation like being stingy or quarrelsome is liable to be smelt out for sorcery or witchcraft accusation. Similarly, the Ibibio look out for such negative image characterization in people, because they know from life experiences that disequilibrium in society is not only caused by spirits, but also by individuals living in the society. They understand that whereas social relations inevitably entail a certain amount of friction, which may be because of breach of moral codes or communal norms and values, perpetrators of acts that violate societal norms are probed for causes of their actions. Assessment of human nature and behaviour that are at variance with societal expectation like subversion of roles, violation of norms and values, breach social order, fragments and disintegrates the society.

Eket people, and the Ibibio in general perceive witchcraft as a world in opposition to that of normal society, favouring individual interest over collective good. Thus, street children are perceived as incarnations of social disintegration, because they violate groups’ expectations of solidarity and sharing that are inherent in communal life and in the current definition of normality through their involvement in witchcraft. On this backdrop, the community does not view them from human rights’ perspective; as vulnerable or helpless victims that elicit sympathy and support. Neither do they consider the community’s response to their behaviours (conducts) as a hysterical overreaction as analyst assumed (Holley, 2016; Ellison, 2018; Hadithi, 2019). This points to the relativity of the concept of meaning, that the meaning people attach to situations or events could stem from their cultural predilections. It thus follows, that the children are rather perceived in emic view, as actors and aggressors, and blamed for their predicaments, being found in opposition as witches, evil and amoral. This opposition from the offort point of view stirs up agitation to what constitutes a deeply moral evil because it can destroy all that the society represents. Regrettably so, when children, on whom posterity depends, become agents of such opposition that takes on a value, as a reality that threatens normative ethos. To this end, they are perceived as undesirable and abhorred by the people as elements disruptive of the social order.

Other dynamics in the Akwa- Ibom street children scam

Having envision from the community’s point of view, the moral concern that justifies the moral panic that informs the abandonment of children on the street, it is pertinent for scientific objectivity, to examine the wider spectrum involved in the Eket street children issue.

It is our observation that the phenomenon of street children in Akwa Ibom goes beyond normative discourse. It hinges on the changing image and the role of children, which may take different forms depending on family’s experiences in terms of misfortunes. It also, latches on the challenges of parenting in a depressed economy. It is quite common in Akwa-Ibom as we observed and confirmed during our visit to their homes to see single parents saddled with the task of raising their children alone. The challenges such parents face in terms of responsibilities and the ability to meet children’s needs is extremely demanding in a depressed local/national economy with high rate of unemployment. Thus, failures to meet up with parental responsibilities are masqueraded through witchcraft labeling. Two residents of Eket in the interview noted with regret, that some people use witchcraft to cover up their inability to cater for their children, whom they cannot adequately care for, due to their financial incapacitation. Worst still, that the kinship system that had been a support to families grappling with economic hardships among the Ibibio has been weakened by individualization as Modo and Chineyemba (2015) studies confirmed.

Another component in the dynamics as earlier hinted, is the materialistic and egoistic interest of some elites who manipulate the existing disequilibrium in the society to assert their opinions on defenseless children, allocating to them a position in the dislocation in the society that has hampered social order. Concealing their latent selfish motives, they pose as exorcists on whose domain resides the exclusive right of exorcism to whom desperate parents’ recourse to. They thus affirm Taussig’s (1980), assertion that the regulation of social activity is computed by men calculating their egoistic advantage over others. Driven by their inordinate passion for wealth, the lucrative enterprise is ostensibly employed to the detriment of vulnerable children whose gory tales reveal the iniquitous violation; they suffer from these elites under the pretense of exorcism. As shepherds, pastors hold influential positions in Eket community that is largely Christian. Therefore, their views are highly sought and respected in spiritual matters and issues of moral concern. Since witchcraft is situated in spiritual realms, their opinions are significant. Little wonder, a parent could abandon his child on the street at pastor’s instruction, as one of the children revealed.

In summary, the study opines that the phenomenon of street children in Akwa-Ibom is multifaceted. On the periphery, it could be a normative search for order, hence interpreted as a sort of cultural resistance to oppositional value that threatens communal bond and social order. Thus perceived, labeling reflects the people’s strong desire for adherence to norms by ensuring conformity as the fear of witchcraft labeling compels members to comply with societal norms and values. Abandonment of children on the street is therefore the community’s effort to reassert norms, reinstate and strengthen social order. But it can also be interpreted differently, especially when viewed as a moral panic, considering that delinquency is a common phenomenon among juveniles. The callous abandonment of children on the street and the security threats it poses, negate social order. Also, from the angle of the material interest and the deceit that shrouds the exercise, particularly the egoistic and mercantile exorcism carried out by the clergy. It reveals the blatant avaricious quest for wealth and the dearth of mutual concern for the afflicted which also violate the Eket/Ibibio sense of brotherhood and communality. Ironically, this greed goes unpunished. It thus glaringly portrays the incongruities in interpretation of collective conscience (offort) and inconsistency in application of sanction to violators, as only vulnerable children are singled out for whatever reasons that are personal and may be consistent or inconsistent with the general will. This further affirms Becker’s assertion that the act of labeling lies in the interest of those that defines it, those he called ‘moral entrepreneurs’ that interpret the behaviours of the children and label them as evil, amoral and elements disruptive of the social order.

In conclusion, this paper assert that the incidence of children living on the street, completely estranged from their family is an abnormality and public display of the failure of parents as custodians of children whose onus it is to see to their welfare, and to inculcate communal norms and values as primary agents of socialization. It is also indicative of the breakdown of communal solidarity and the sense of brotherhood that obligate members of the extended family/community as partners with children upbringing. Again, the selectivity in the application of sanctions to deviation from the collective conscience (offort) across groups is a blatant display of irregularity that contradicts the moral value and the social order it purports to strengthen. It is concluded thereof, that the phenomenon of street children in Akwa-Ibom state is an erroneous search for order because the extremity of the sanction defeated its traditional goal of preserving social order.

In view of the above discourse, it is recommended that:

1. Parents should effectively inculcate societal norms and values to their children.

2. Conscientious efforts should be made by governments and human rights activists to enlighten parents and community leaders on the rights of children.

3. Children on their parts should obey their parents and abide by their instructions.

4. Advocates of children’s rights and social analysts should understand the local context and give credence to a communal value system.

5. There should be consistency in interpretation of societal/moral values to avoid discrimination and favouritism.