The main purpose of this research was to assess the current position of business education; the need to reposition business education for post oil-boom economy; and the possibilities of repositioning business education for post oil-boom economy. A total of 132 business educators from universities and colleges of education in Edo and Delta States participated in this study. Survey design was employed as the data collection method for this research. A four point scaled questionnaire was used for the data collection. The instrument attained a Cronbach alpha value of 0.85. the data were analyzed using mean and standard deviations calculations, while three hypotheses were tested using t-test statistic. The results show that the current position of business education is inadequate in terms of resources and without the capacity to equip students with the requisite attributes that would inspire them to start and operate their own business and become self-reliant in post oil-boom economy. It further showed that adequate optimization of resources would help to reposition business education for post oil-boom economy. There was no significant difference between the mean ratings of business educators in universities and colleges of education on the current position of business education; no significant difference between the mean ratings of business educators in Edo and Delta States on the need to reposition business education for post oil-boom economy; and no significant difference between mean ratings of male and female business educators on the possibilities of repositioning business education for post oil-boom economy. It is recommended that government and other relevant stakeholders should endeavour to invest their resources (both financial and otherwise) on business education in order to help in repositioning the programme for post oil-boom economy.

Since the introduction of business education over four and a half decades ago, the programme has made modest impact not only on teaching profession, but also on economic growth and development in Nigeria (Ekpenyong and Nwabuisi, 2003). In order to promote economic competitiveness, some countries across the globe have taken the lead to invest sufficient amount of resources (both human and material) into Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) sector (Cantor, 1985; Ul-Haq and Haq, 1998; Tilak, 2002; Asian Development Bank, 2004; Agrawal, 2013), of which business education is a major component. As such, a well implemented business education aims at achieving three broad goals:

1. To prepare the recipients for career in office occupations;

2. To equip recipients with the requisite attributes for job creation and entrepreneurship; and

3. To expose recipients with knowledge about business including a good blend of computer technology, which incorporates the Information and Communication Technology (ICT)?

The first two goals involve education ‘for’ business which aims at equipping students with the requisite skills to become gainfully employed in the world of work, whereas the later involves education ‘about’ business which aims at providing a sound basis for further education at the graduate and post-graduate levels. Given this dual goal and mission, it is quite clear that business education programme is far more than preparing recipients to become more employable, but also to equip them with the requisite attributes for lifelong learning. Soneye (2000) and Osuala (2004) both agreed that business education consists of two parts, namely:

1. Office education, and

2. General business education.

They further remarked that office education is a vocational programme of instruction that prepares the recipients for employability and careers in office occupation, while general business education provides them the information and knowledge for the launching and management of personal business activities. Accordingly, business education can be described as a systematic programme of instruction that offers various skills in accounting, marketing, and Office Technology and Management (OTM). If these skills are well-taught and properly inculcated, they would help in preparing students for gainful employment after graduation as well as stimulate their interest for further education at the graduate and post-graduate levels. Generally, researchers and educators have found that exposing recipient’s to certain types of TVET programmes would help in promoting sustainability in terms of national development with relatively peace and security (Ekpenyong, 2010; Majumdar, 2011; Pongo et al., 2014).

Particularly, business education that provide practical learning environment or real-world experience for effective instructional delivery appear to be very useful in equipping recipients with requisite knowledge, skills and attitudes that would inspire them to start and operate their personal business, and become self-reliant after graduation (Ebinga, 2014). As pointed out earlier, business education is aimed at preparing the recipients to explore viable job opportunities in office occupation and further education at graduate and post-graduate levels. If these are the two basic goals and missions of business education programme in Nigeria, the question becomes:

“Why is the rate of unemployment and underemployment still increasing drastically particularly among business education graduates?”

The National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) (2016) pointed out that the unemployment rate has increased from 13.3% in the second q quarter of 2016 to 13.9% in third quarter of 2016, while the underemployment rate has increased from 19.3% in the second quarter of 2015 to 19.7% in third quarter of 2016. The NBS (2016) also stipulated that a total of 27.12 million people were either unemployed or underemployed in the labour force in third quarter of 2016, compared with 26.06 million in second quarter of 2015. The report showed that the economically active population or working age population (persons within ages 15 to 64) increased from 106.69 million in second quarter of 2016, to 108.03 million in third quarter of 2016. In third quarter of 2016, the labour force population (that is those within working age population willing, able and actively looking for work) increased to 80.67 million from 79.9 million in second quarter of 2016, representing an increase of 0.98%. This means that 782,886 economically active persons within the age of 15 to 64 entered the labour force between July 01, 2016 and September 30, 2016.

Within the same period, the total number of people in full employment (who did any type of work for at least 40 h) decreased by 0.51% (272,499). Using the previous unemployment report of the NBS, about 50% of Nigerians between the ages of 15 and 24, and living in the urban areas were unemployed in 2009, about 17.3% of those in the age group of 25 to 44 were unemployed in the same year, while 10% of those within the age group of 45 to 59, and living in the urban areas were unemployed in the same year (NBS, 2011). The aforementioned report has however shown that the rate of unemployment is higher among youths including business education graduates in Nigeria. However, efforts to improve the quality and standard of business education programme in order to help in reducing this socio-economic problem appear to have been slowed down by a number of factors. Prominent among these factors are: low public interest, curriculum structure, insufficient manpower and inadequate material resources (Ekpenyong and Nwabuisi, 2003; Agbo, 2012; Njoku, 2012; Agboola, 2015; Oladunjoye, 2016). Similarly, the reasons behind poor delivery of business education programme in Nigeria may be that instructional methods are inappropriate, entrepreneurs are not involved, student’s attitude towards the programme is poor, lecturers are not fully competent, and practical element is missing (Edokpolor and Somorin, 2017).

The existence of the aforementioned challenges is a mere pointer to the fact that business education programme is currently delivered theoretically and as such not capable of equipping its recipients with the requisite knowledge, skills, and attitudes to explore business or entrepreneurial opportunities in post-oil boom economy. This means that business education students are train to be employees who will act as followers of few ‘employers of labour’, yet it is expected that more and more students of business education will own businesses instead of working for others. As such, they need to constantly, quickly, and efficiently acquire/learn new skills and information to function effectively as entrepreneurs in post-oil boom economy. Learning or acquiring new skills would help them to assume leadership roles, and skills such as: creativity, innovativeness, self-efficacy, risk-taking, tolerance for ambiguity, internal locus of control, need to be emphasized. An oil boom may be defined as a tremendous increase in the production of oil and natural gas resources as a result of exploitation of mineral oil. Generally, an oil boom is seen as a short period that initially brings economic benefits, in terms of increased growth in Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Within this short period, oil boom has brought about a great revenue turnaround for Nigeria and brought her to international limelight as a major oil producing country in Africa, the eleventh largest producer of crude oil in the world, and has a potential of increasing oil production capacity to four million barrels per day in the year 2010 (Akuru and Okoro, 2011).

Unfortunately, Nigeria entered into a recession having recorded two quarters of consecutive negative economic growth in the first and second quarter of 2016 (First Security Discount House Research, 2017). This negative situation have giving credence to the theory of dwindling oil reserves proposed by Hubbert (1956) who developed a mathematical model that assumes that the production of oil resource follows a bell-shaped curve, one that rises rapidly to a peak and declines just as quickly. Factors that led to the negative economic growth in first and second quarter of 2016 are: drop in oil production; foreign exchange shortages; non-payment of salaries; weak electricity generation; and low investors’ confidence (FSDH Research, 2017). This means that Nigeria would experience economic growth if oil production increases. The increase in oil production can only occur on a sustainable basis provided there is peace in the Niger Delta region. This is expected to come to fruition following the renewed negotiation with the aggrieved parties in the region, which would stop vandalism of oil facilities and encourage oil production. This would increase the supply of foreign exchange to the manufacturing sector of the economy.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2017) stated that economic activity in Nigeria is projected to improve from 2.7% in 2015, to 1.5% in 2016, to 0.8% in 2017, and to 2.3% in 2018 respectively. The World Bank (2017) also stipulated that the GDP growth of Nigeria is expected to increase from 1.7% in 2016, to 1.0% in 2017, to 2.5% in 2018, and to 2.5% in 2019, as a result of oil exploitation. The IMF (2017) further pointed out that the policy stimulus and improvement in commodity prices will aid the growth. These projections requires TVET programmes to be responsive and thus gradually repositioning their instructional approach to a more practical approach in order to help equip students with the requisite attributes for entrepreneurial activities in post-oil boom economy. Responsiveness to post-oil boom economy is particularly relevant for business education in that managers of the programme need to ensure the adequate optimization of funds; adequate supply of manpower in terms of quality and quantity; adequate procurement of infrastructural facilities and equipment; and adequate utilization of quality curriculum. This is because business education is a skilled-based programme of instruction which aimed at preparing students to become qualified for a particular profession particularly after tertiary education level (for example accountant, marketer, or office technologist and manager). These professions would help business education graduates to explore business opportunities in post-oil boom economy.

From the foregoing, one would agree that business education is one of the occupational areas that can richly equip students with requisite attributes to explore business opportunities in post-oil boom economy. The skills of business education are very useful in any office, factory floor, and computerized environment. This may account for why business education remains one of the few skills development programme in Nigeria that require beneficiaries to undergo series of systematic testing and interviews before being employed, promoted or dropped. For instance, accounting skills is concerned with the preparation of accounting information, such as: ledgers, account from the vouchers, cash books, wages and salaries administration, skills for collecting and recording various pieces of accounting information, and of making monthly statement of accounts. Hence, accounting skills can provide occupations in consultancy services to customers who are interested in their entrepreneurial businesses to be either audited or to produce financial status by calculating the trading profit and loss accounts, and the balance sheets. This will give way to advising customers on the true financial position of their business enterprises. Examples are: petrol stations, departmental stores, motor transport companies, private schools, business centers, faith-based organizations, non-governmental agencies, cooperative societies, and so on.

Marketing skills is concerned with the buying and selling of goods and services, including advertising and sales promotion. In marketing education, students learn about planning, pricing, promoting, and distributing products, goods, services, roles and responsibilities of consumers and producers, and the impact of their decisions on the marketplace. Many graduates of business education would find viable occupations in this segment of business education. They buy goods from production companies and sell in other areas of demand. Examples are: motor-spare parts, trading in food stuff (including palm oil, grand nut oil and vegetable oil), import and export, being engaged in petroleum products distribution, bookshop management, furniture business, decoration services, hotel/eateries centers or large-scale bukateria management, and many more. OTM skills is concerned with the provision of knowledge, skills and attitudes necessary to perform successfully in clerical and administrative management positions in entrepreneurial business ventures. Many professionally-trained office technologists and managers can either take up paid employment in oil companies or be self-employed by setting up their own documentary services popularly known as ‘business center’ in Nigeria as they develop a high level of skills in word processing and document formatting.

Although, this occupation is resource-based, and as such office managers and technologists as entrepreneurs should be able to raise initial capital to procure facilities and equipment to start and manage business centers. An office technologist and manager may also employ some supporting staff, which includes: messengers, cleaners, dispatch riders, technicians, book-binders, computer operators, telephone operators, office assistance or clerks, fax machine operators, suppliers of various stationeries items, equipment and spare-parts. The research proceeds by first providing an explanation of the fact that there is need to reposition business education for post-oil boom era. This is followed by a systematic explanation of the procedures that show how the research was conducted. Analyses of research questions and testable hypotheses are then presented. Next, major findings from the data analyzed are further discussed. Finally, the authors drew a logical conclusion based on the findings of the research.

Statement of the problem

Business education is a systematic programme of instructional delivery aimed at equipping students with the requisite knowledge, skills, and attitudes to explore entrepreneurship activities and further education at the graduate and post-graduate levels. Despite these laudable objectives and missions, available evidences have shown that Nigeria is handling this programme with levity (Ekpenyong and Nwabuisi, 2003; Obunadike, 2015; Oladunjoye, 2016). This situation has consequently starved business education with adequate provision of financial resources, adequate provision of manpower in terms of quality and quantity, adequate supply of the state-of-the-art facilities, and proper utilization of quality curriculum, coupled with proper attention. As a result of inadequate optimization of resources in terms of quality and quantity, the instructional delivery of business education tends to be more theoretical in nature, and as such making the programme not to be capable of equipping her students with the requisite knowledge, skills, and attitudes to explore entrepreneurial opportunities in post-oil boom economy. The implication is that graduates of business education would not be prepared well enough and lack basic skills for employability in post-oil boom economy. Hence, this research sought to provide a descriptive data on the current position of business education, the need to reposition business education, and the possibilities of repositioning business education for post-oil boom economy.

Purpose of the study

The specific purpose of this research was to:

1. Determine the current position of business education programme.

2. Determine the need of repositioning business education for post-oil boom economy.

3. Determine the possibilities of repositioning business education for post-oil boom economy.

The design of this research was a survey design. It is a non-experimental design (Mitchell and Jolley, 2007) aimed at collecting data, describing it in a systematic manner, the characteristics features and facts about a population (Ary et al., 2010; Omorogiuwa, 2006). The total population consists of 132 business educators from universities and colleges of education in Edo and Delta States. There was no need to employ any sampling technique, nor select any sample size for the study because the population was not too large to cover. Therefore, the entire population was used in the research study. The instrument for data collection was a structured questionnaire and was validated by two experts. The reliability was determined by administering the instrument to 20 business educators who were not part of the research. Their responses were analyzed using the Cronbach alpha method, which yielded a coefficient value of 0.82. The instrument was further administered to the respondents with help of two trained research assistants. The questionnaire was retrieved as soon as they were completed. Out of 132, 127 pieces of the instruments were retrieved. The data collected from the respondents were analyzed using mean, standard deviations and t-test statistics. The mean was used to answer the research questions while the t-test was used to test the hypotheses at .05 level of significant.

The standard deviations were used to determine the extent to which the responses were clustered to or deviated from the mean responses. The decision rule for the research questions was based on any calculate mean equal to, or greater than 2.50 means that business educators agreed with the questionnaire items raised; while any calculated mean less than 2.50 means that business educators disagreed with the questionnaire items raised. Also, any standard deviation value between 0.00 and 0.96 revealed that business educator’s responses are very close, meaning that business educator’s responses are clustered around the mean. Furthermore, the value (p) was used in taking the decisions on the hypotheses. If the p-value is less than or equal to 0.05, the null hypotheses is rejected, but if the p-value is greater than .05, the null hypotheses is retained. The value (p) was used to take decisions on hypotheses. If p-value is less than or equal to 0.05, the null hypothesis is rejected, but if p-value is greater than 0.05, the null hypothesis is retained.

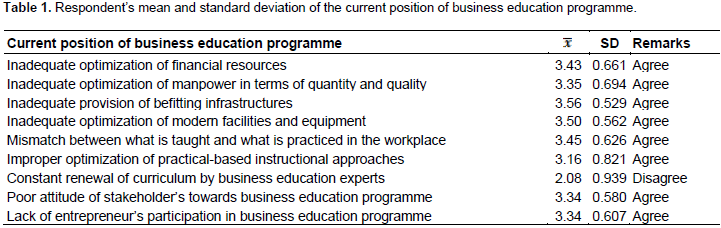

The data collected from the respondents were analyzed using mean ( ) and Standard Deviation (SD), and the results are presented in Tables 1 to 3.

Research question 1: What is the current position of business education programme?

Results of the data presented in Table 1 show the mean ratings of business educators in universities and colleges of education on the current position of business education. The results revealed that out of 9 items, only 8 items had the mean ratings that range from 3.16 to 3.56, while the corresponding standard deviation values ranged from 0.529 to 0.821. However, 1 item had a mean score of 2.08; with the corresponding standard deviation value of 0.939. The mean ratings are indications that business education is currently starved with adequate provision of resources (both human and material), and indeed has contributed to the theoretical nature of the programme, while the standard deviation values are indications that respondent’s opinion are very close.

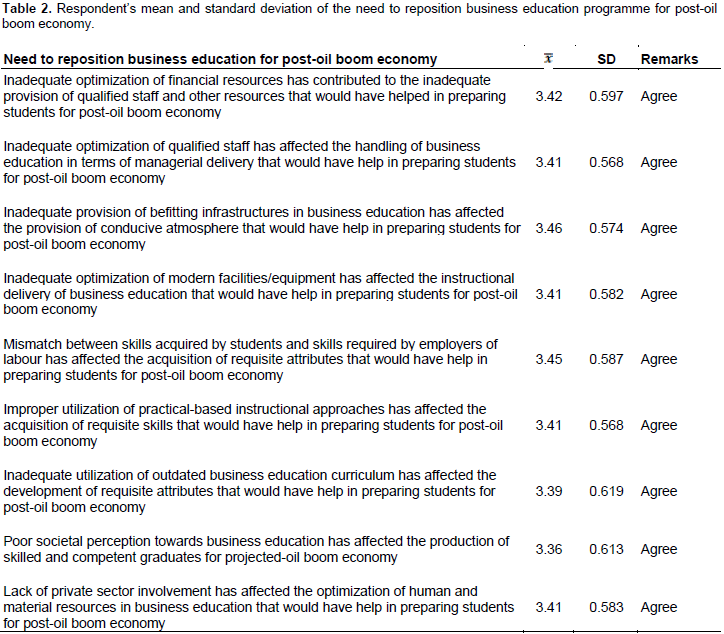

Research question 2: What is the need of repositioning business education for post-oil boom economy?

Results of the data presented in Table 2 show the mean ratings of business educators in Edo and Delta States on the need to reposition business education for post-oil boom economy. The results revealed that 9 items had the mean ratings that range from 3.36 to 3.46, while the corresponding standard deviation values ranged from 0.568 to 0.619. This is an indication that the optimization of resources, coupled with effort to orient the mindset of Nigerians would assist in repositioning business education for post-oil boom economy, while the standard deviation values are indication that respondent’s opinions are very close.

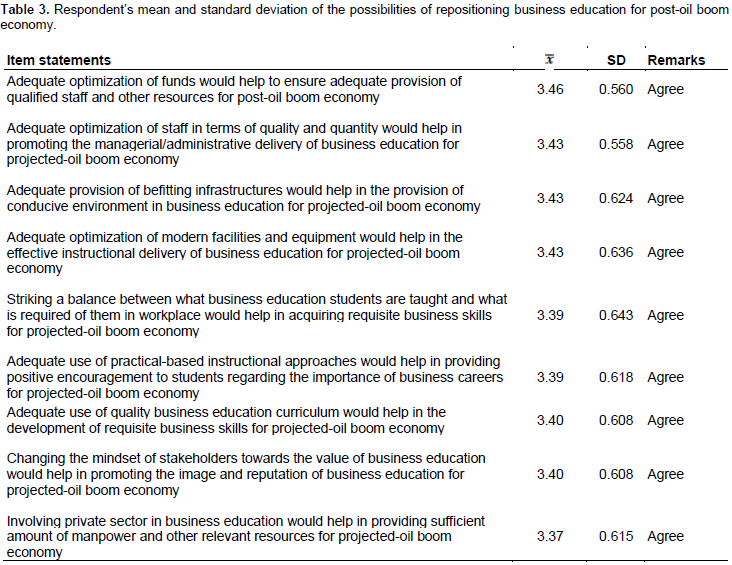

Research question 3: What are the possibilities of repositioning business education for post-oil boom economy?

Results of the data presented in Table 3 show the mean ratings of business educators on the possibilities of repositioning business education for post-oil boom economy. The results revealed that 9 items had the mean scores that range from 3.37 to 3.46, while the corresponding standard deviation values ranged from 0.558 to 0.643. This is an indication that the optimization of resources, coupled with effort to orient the mindset of Nigerians would assist in guaranteeing the possibilities of repositioning business education for post-oil boom economy, while the standard deviation values are indications that the respondent’s opinions are very close.

Testing the hypotheses

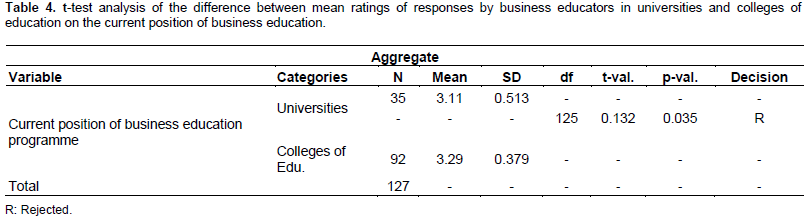

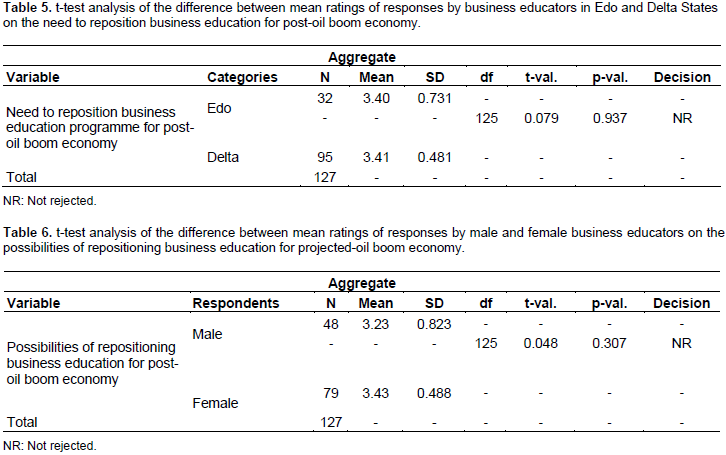

The data analysis for testing the hypotheses was carried out using the t-test statistic. The results are presented in Tables 4 to 6.

Hypothesis 1: There is no significant difference between the mean ratings of business educators in universities and colleges of education on the current position of business education. The results presented in Table 4 shows that the aggre-gate mean ratings of business educators in universities and colleges of education on the issues facing business education is 3.11 and 3.29, while the corresponding standard deviation is 0.513 and 0.379. The results in Table 4 indicated that the t-value is 0.132 at df of 125, while the p-value is 0.035. Testing at alpha level of 0.05, the p-value is significant, since the p-value is not greater than the alpha value (0.05). Therefore, the null hypothesis is rejected; hence, there is significant difference between the mean ratings of business educators in universities and colleges of education on the current position of business education programme.

Hypothesis 2: There is no significant difference between the mean ratings of responses by business educators in Edo and Delta States on the need to reposition business education for post-oil boom economy. The results presented in Table 5 shows that aggregate mean ratings of business educators in Edo and Delta States on the need to reposition business education for post-oil boom economy is 3.40 and 3.41, while the corresponding standard deviation is 0.731 and 0.481. The results in Table 5 indicated that the t-value is 0.079 at df of 125, while the p-value is 0.937. Testing at alpha level of 0.05, the p-value is not significant, since the p-value is greater than the alpha value (0.05). Therefore, the null hypothesis is not rejected; hence, there is no significant difference between the mean ratings of business educators in Edo and Delta States on the need to reposition business education for post-oil boom economy.

Hypothesis 3: There is no significant difference between the mean ratings of male and female business educators on the possibilities of repositioning business education for post-oil boom economy. The results presented in Table 6 shows that aggregate mean ratings of male and female business educators on the possibilities of overcoming the issues and challenges facing business education is 3.32 and 3.43, while the corresponding standard deviation is 0.823 and 0.488. The results in Table 6 indicated that the t-value is 0.048 at df of 125, while the p-value is 0.125. Testing at alpha level of 0.05, the p-value is not significant, since the p-value is greater than the alpha value (0.05). Therefore, the null hypothesis is not rejected; hence, there is no significant difference between the mean ratings of male and female business educators on the possibilities of repositioning business education for projected-oil boom economy.

The aim of this research in the first instance was to assess the current position of business education. Secondly, the research aims at investigating the need to reposition business education for post-oil boom economy. Lastly, the research aims at investigating the possibilities of repositioning business education for post-oil boom economy. One of the major finding in this research is that business education programme is currently starved with adequate provision of resources in terms of human and material, and as such it has resulted to theoretical delivery of the programme. However, this unpleasant situation has been supported by so many authors both theoretically and empirically. Theoretically, these authors had remarked that efforts to improve the quality and standard of business education in Nigeria have been slowed down by a number of factors, such as: low public interest, curriculum structure, and inadequate supply of quality human and material resources (Ekpenyong and Nwabuisi, 2003; Agbo, 2012; Njoku, 2012; Agboola, 2015; Oladunjoye, 2016).

Empirically, Edokpolor and Somorin (2017) further found that the main reasons behind the theoretical delivery of business education in Nigeria is that teaching and learning methods are inappropriate, entrepreneurs are not involved; student’s attitude towards the programme is poor, lecturers are not fully competent; as well as, practical element is missing. The second finding in this research is that there is inadequate optimization of resources, coupled with poor negative perception towards business education programme. This unpleasant situation tends to have hindered the acquisition of knowledge and skills for entrepreneurial careers and life-long learning (Ekpenyong and Edokpolor, 2015a; Edokpolor and Egbri, 2017). More recently, the study conducted by the FSDH Research reported that the Nigerian economy entered into a recession having recorded two quarters of consecutive negative economic growth in first and second quarter of 2016; and one of the prominent factors that led to this situation is the drop in oil production, due to the disruption in oil production (FSDH Research, 2017). The IMF and World Bank stipulate that economic activity and gross domestic product (GDP) growth in Nigeria are projected to increase as a result of oil production (IMF, 2017; World Bank, 2017).

These situations have necessitated the need to reposition business education for viable job opportunities in post-oil boom economy. The third and final finding in this research is that the optimization of resources, coupled with the effort to orient the mindset of Nigerians would assist in guaranteeing the possibilities of repositioning business education for post-oil boom economy. It quite clear that the optimization of resources (both human and material) would help to guarantee the possibilities of repositioning business education programme for post-oil boom economy. Scholars and educators have recently argued that the effort to optimize resources would help to equip business education students with the requisite attributes for entrepreneurial startup and management, instead of working for others (Ekpenyong and Nwabuisi, 2003; Ekpenyong and Edokpolor, 2015b; Edokpolor and Egbri, 2017).