ABSTRACT

This study analyzes the range of vulnerabilities among the left behind women (LBW) and their coping strategies primarily focusing on Self Help Groups (SHGs). The basic data used in this paper were collected as part of the Mid Term Review of a cross country intervention on Enhancing Mobile Populations’ Access to HIV&AIDS Services, Information and Support (EMPHASIS) in South Asia in 2012. The reproductive vulnerabilities of the left behind women like sexually transmitted infections (STIs), reproductive tract infections (RTIs), human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) are primarily due to the risky sexual behaviour of husbands at destination. The other vulnerabilities faced by the left behind women are the lack of capacity in treatment seeking, physical harassments and social vulnerabilities with the blind administrative response. The self-help groups have proved to be a boon in the life of these left behind women in Bangladesh and have also moulded their lives for beneficence. Compared to their previous lives without the association of self-help groups, left behind women can now address their vulnerability to HIV/AIDS and impart this knowledge to their husband and ask them to abstain from sex in India or to have safe sex with female sex workers (FSWs). Self help groups also have impacted their social and financial positions reducing social harassment. The mobility of the left behind women has increased in and outside community improving their treatment seeking behaviour. They have now become literate about their sexual and reproductive rights and negotiate with their husbands to use condoms when they come back.

Key words: Left behind women, cross border migration, Bangladesh, reproductive vulnerability, HIV & AIDS.

Men crossing borders for employment, business, and better opportunities is a natural phenomenon witnessed across developed and developing countries all over the world, much beyond documented and legal migration. Being the most developed of all South Asian countries; India has been the most sought destination by immigrants from neighbouring countries. India has a 4097 km border with Bangladesh along West Bengal, Assam, Meghalaya, and Tripura. Of this, only around 1500 km is fenced, leaving a major portion of the border porous and easy for in-migration. A large influx of undocumented migration occurs from Bangladesh to India, leaving behind their wives and families. Migrant Bangladeshis are more concentrated in West Bengal and Assam. Geographical contiguity, socio-cultural affinity, the kinship factor and historical reasons have left the Indo-Bangladesh and Indo-Nepal borders vulnerable to migration (Behera, 2011). Nepal and India have an ‘open-border’ policy adopted by both Governments through the 1950 Bilateral Peace and Friendship Treaty allowing free movement of people and goods between the two nations, but for Bangladeshis, however, official migration to India is fraught with problems and most migrants to India are unauthorised since there is no such treaty between India and Bangladesh (Samuels and Wagle, 2011).

Census (2001) reported that 5.1 million persons in India as migrant by last residence from across the International border. Approximately 3 million out of the total immigrants in India comprises of Bangladeshi Migrants. The exodus from Bangladesh into India has, for the first time, been termed by the United Nations as “the single largest bilateral stock of international migrants” in the eastern hemisphere and, in the developing world (Sinha, 2013). Crossing borders has been central to the lives of many Nepalese and Bangladeshis as they move to and fro between their countries and India in the hope of better opportunities for themselves and their families (Samuals et al., 2011). These migrants generally find work in the informal sector, often as domestic workers, construction labourers, rickshaw pullers and rag pickers (Naujoks, 2009). These people become socially vulnerable and start living in an unhygienic environment. Along with other health related issues, the migrant population group especially is vulnerable to HIV and AIDS due to risk behaviours and alternate support at the destination (Azim et al., 2008; Samuals et al., 2011).

Migrants commonly have multiple sexual encounters, change partners and use condom infrequently both in India and back home with their left behind women. Several factors including peer pressure, cheaper sex, lack of family restraint, alcoholism and low perceived vulnerability to HIV/STIs influence migrants to practice high-risk sexual behaviour at the destination. They also play possible roles in increasing HIV/AIDS vulnerability of their women and home country (Poundel et al., 2003). Back home their lefts behind women also are vulnerable and exposed to harassments, illness and fail to run their family. Those left at home may face loneliness and exclusion and also may engage in risky behaviours for livelihood and survival purposes (Samuels and Wagle, 2011).

Young migrant workers away from their friends, spouse, families and communities often experience feelings of isolation and loneliness that can lead to drug use and sexual activity that puts them at increased risk for HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS, 2001). Studies conducted in other countries show that economic mobility and migration can make people more vulnerable to HIV/STI infections (Decosas et al., 1995; Wolfers and Fernandez, 1995; UNAIDS, 2001). High prevalence of sexual risk behaviour has been found among work migrants, and mobile workers in many countries and the major role of this in HIV transmission is well established (as cited in Mercer et al., 2007). Pison et al. (1993) also showed that men contract HIV through HIV-positive women while they are away from home and then transmit it to their wives when they come back. Women and wives are in a passive and vulnerable position to contract HIV from migrant husbands (Nguyen, 2005).

Migration-related changes can also negatively impact women’s status. This is particularly true if male out-migration results in an increased work burden for the women left behind, if the women are unable to access or mobilize resources in the absence of their husband, or if the women are abandoned or do not receive enough remittance money to cover basic household needs (McEvoy, 2008). The problem of the left-behind woman has attracted growing concern from society with ever increasing numbers of male labourers leaving the countryside for work in the city. As a vulnerable group, these left-behind women face security issues and bear a heavy physical and psychological burden back home (as cited in Jacka, 2014). When the husband of a family leaves, the woman who is left behind has to independently shoulder the responsibility for agricultural production, raising the children and supporting the elderly. They are therefore weighed down with the double pressures of additional work and psychological burdens (Jingzhong, 2008). Left-behind women, children and the elderly are often depicted as “vulnerable groups” who suffer insecurity, stress, loneliness, depression, and ill-health as a result of their abandonment (Jacka, 2014). Across rural India, the phenomenon of migration creates an entire class of women left behind to fend for themselves in the face of increased vulnerability to neglect, discrimination and psychological as well as physical abuse (Awasthi, 2014).

In reducing women’s vulnerability in all streams be it in reducing poverty, to induce education or to socially uplift their position, self help groups are a well known concept in Bangladesh which now has evolved as a movement. That is why; the key question to be addressed in this paper is the supportiveness of SHGs in reducing the reproductive vulnerabilities of left behind women (LBW). It has been proved in literature that self help groups have been a boon to the life of women in many low-income countries and helped in their empowerment (Anand, 2002; Manimekalai and Rajeswari, 2002; Tirupal,2016, Chatterjee, 2014). Self-help groups (SHGs) are considered as one of the most significant tools to adopt a participatory approach to the empowerment of women. SHGs help in the empowerment of women both social and economically (Gupta and Gupta, 2006).

Khandker et al. (1995) traced the origin of Grameen Bank, which was started in 1983 in Bangladesh by Prof. Mohammed Yunus, where the role of micro credit in facilitating women’s potential was observed. In another study on Bangladesh, Sultana (1988) concluded that women’s group formation, regular savings and income, new knowledge, consciousness raising and group mobilisation can together create an alternative to women’s traditional condition and contribute to women’s ability to speak out and earn a relatively higher status in the family and in the village. Study on the group empowerment process confirms that participation in community and self-development programmes through organisation is the only way out for voiceless women (Vijayanthi, 2002).

As the cross border migration has implications on both destination and source countries, this paper is motivated against the grain of discourse on the vulnerability of the left behind focussing on the Bangladeshi women whose husbands have migrated to India for better opportunities and employment. The main aim of this paper is to analyse the reproductive vulnerabilities among the LBW due to the migratory status of their husbands and to explore the potential role of self-help groups as coping mechanism of LBW.

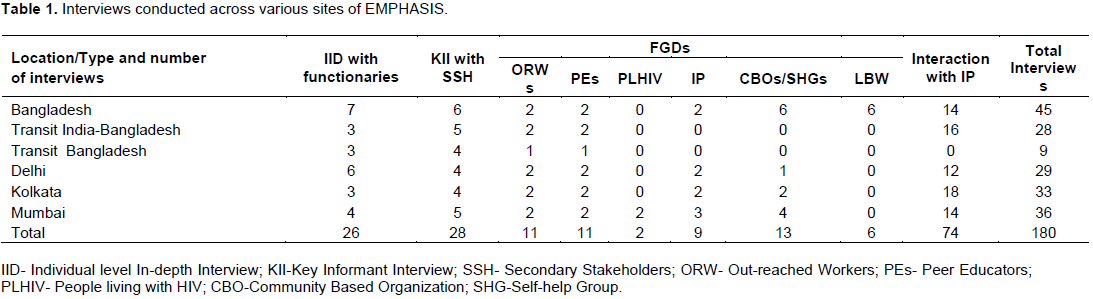

The basic data used in this paper were collected as part of the Mid Term Review of a cross country intervention on Enhancing Mobile Populations’ Access to HIV&AIDS Services, Information and Support (EMPHASIS) in South Asia in 2012. The mid-term review focuses at the progress made so far in achieving the project’s goals and objectives by analyzing its relevance, effectiveness and efficiency. The key issues and challenges for the reproductive vulnerabilities of LBW are based on a total of 180 interviews conducted across various sites of EMPHASIS (Table 1). It covers the perception and experience of beneficiaries. Qualitative insight into the process through which cross border migration affects the life of LBW, was primarily based on a set of qualitative interactions with key stakeholders, by conducting focus group discussions, in-depth interviews and key-informant interviews.

EMPHASIS has been implementing comprehensive programs and services at source for reducing the impact population’s (especially women’s) vulnerability, to HIV/AIDS, by raising awareness of HIV/AIDS, capacity building, improving the use of health care services by developing a range of support structures, and creating an enabling environment for behaviour change.

The checklists developed for the FGDs among LBW covered their problems before and after their husband’s migration, social harassment, sexual harassment, reproductive morbidities, treatment seeking behaviour and the type of support structure by the SHGs. On the other hand, the major contents of the check list for the FGDs among SHGs contained various components and strategies of SHGs to enhance community mobilization for effective functioning, capacity building efforts among the LBW as well as strategies to strengthen support system by networking. These information have been helpful in accessing the situation of LBW in the context of cross border migration and the potential role of SHGs as a coping mechanism for the women.Insights have also been obtained from Health Belief Model and Risk Reduction Model and Behaviour Change Models for Reducing HIV/STD Risk. The Health Belief Model is the most commonly used theory in health education and health promotion and can explain the health behaviour. Perceived susceptibility and perceived severity determines the perceived threat and gradually the likelihood of behaviour. The health behaviour also gets influenced by perceived benefits and other modifying factors (Janz and Becker,1984).Here the SHGs are acting as benefits and Cues to action for the LBW and influencingtheir perception and behaviour and indirectly their husband’s behaviour also. AIDS risk reduction model which characterizes people’s efforts to change sexual behaviour related to HIV transmission has also aided in the conceptualization of this study. This model comprises of three stages: (a) recognition and labelling of one's sexual behaviours as high risk for contracting HIV, (b) making a commitment to reduce high risk sexual contacts and increase low risk activities, and (c) seeking and enacting strategies to obtain these goals (RCAP, 1995).

In the present study the SHGs are helping the LBW in the first stage and the last stage actively and in the second phase passively. Thus based on the data and the aforesaid frameworks and model the study was accomplished.

Vulnerability among LBW in Bangladesh

Cross border undocumented migration of the male Bangladeshi migrants is involved with manifold vulnerabilities in the lives of the migrants (at destination) as well as in the lives of their wives and families who are left behind in the source countries. The major kinds of vulnerabilities they face are often associated with health, social and economic vulnerabilities. Human Rights get threatened at a macro level, and deprivation of social entitlements, ownerships, access to the social infrastructures, all or certain social rights can be placed under the framework of the social vulnerability at a micro level. At the destination, the migrants consider themselves to be socially excluded as they are generally not welcome in the mainstream of the population and they also have the fear to mix up with the other local population.

On the other hand without the spousal support and in the absence of their husbands the left behind women face social vulnerabilities at the source countries. Health problems like dengue, dysentery and fevers are often seen among the migrants commonly due to low hygienic conditions and poor sanitation in the areas where they live thus bringing the crisis to their lives. Back home, the women find it difficult to run the family and are unable to provide treatment to themselves or children when they fall sick.

Though primarily the LBW of Bangladesh are left behind due to poverty and unemployment but sometimes the reason changes and they are left behind forever over lucrative jobs and extra-marital relations by their husbands at the destination places. The age long vulnerability that these left behind women face are STIs, RTIs, HIV/AIDS, social and physical harassment from family and local people as well as the blind response from the local administration. These vulnerabilities get doubled due to illness, poverty, lack of spousal support and communication. They really get left behind from all arenas of life starting from self-esteem to healthy social life. The vulnerabilities of the LBW have been discussed below.

Reproductive vulnerabilities among LBW

LBW in Bangladesh become more vulnerable towards sexual harassment by family members, relatives, and outsiders since their husbands are away from home. Teasing and taunting by men in the locality is an everyday phenomenon in the lives of these women. Societal and familial isolation forbids them to take any step, and they bear the sexual harassment silently thus increasing their reproductive vulnerability.

A Large majority of LBW are becoming vulnerable due to the behaviour of migrants at the destination, which is virtually a function of risk environment at metropolitan cities of India, having liberalized sexual norms, plenty of sexual opportunity and higher incidences of paid and casual sex. Despite program implementation at transit areas, many of the returnee migrants are getting HIV but not disclosing it to their wives thus increasing their reproductive vulnerability. At the destination, their husbands indulge in sex with other women and female sex workers (FSWs) at the destination. After returning home, the husbands force their wives for sex, and the women cannot deny for sex even after knowing their vulnerability to HIV/AIDS. Moreover, condom use by their husbands is also very inconsistent and often they have unsafe sex. The study by Cruz (2000) noted that many migrants particularly single or those leaving their families behind tend to seek comfort in intimate relationships developed while away from families or relax and enjoy by engaging themselves in casual or paid sex.

The incidence of condom use among the migrant workers is low because of poor accessibility, hesitation in buying condoms, uncertainty about the protection they provide, and reluctance to use them in intimate or steady relationships. The husband-wife communication among the Bangladeshi migrants and their wives is also very limited, increasing the reproductive vulnerability of the LBW of Bangladesh. Bose (2001) also pointed out that left behind women in the state of Himachal Pradesh in India live an isolated life and hardly have any communication with their husbands. Samuels et al. (2014b) found that those women left at home may also face loneliness and exclusion and may engage in risky behaviours for livelihood and survival purposes - particularly if the hoped-for remittances from migrants do not materialise and can also be exposed to HIV infection by returning spouses or partners who may not be aware of their own HIV infection. Roy (2011) found that other than migration factors, extra marital relation and other habits of husbands and marital duration emerged as the significant determinants of STIs/RTIs among the left behind women of rural Bihar, India. Of course, the likelihood of reporting any symptoms of reproductive morbidity was found higher among those left behind women as compared to wives of non migrants.

Migration appears as the stimulant factor for the risky sexual behaviour among migrants, which further result in the transmission of STIs to their wives as the place of origin. There was a consensus among the left behind women during focus group discussions that they are innocent victims of the extramarital sexual behaviour of their husbands at the place of destination.

Other vulnerabilities of the LBW

Jety’s study (1987) on internal migration found that after migration of males, in most cases left behind wives shoulder the responsibility of taking care of children and manage several major and minor crisis in the family single-handedly. Many of the women experience heightened psychological stress, and there is hardly any increase in their status in the family and society. Most of the left behind women in Bangladesh highlighted during their FGDs that adjustment in the family without husbands and the spousal support is very challenging and thus makes a woman at a high risk of isolation, a similar finding as reported by Roy (2011) in the case of rural Bihar. Roy (2011) has also noted that instead of providing help, relatives of the left behind women try to snatch away their resources and takes undue advantage of their situation. The livelihood of the left behind women and their children in Bangladesh mainly depends on the remittance sent by their husbands from the destination. The remittances sent by the male migrants are not regular and most of the times are not sufficient for the LBW to manage household expenses. The LBW face problem during their illness or when their children and other family members are ill since they remain with very little or no money for the treatment. The LBW’s mobility to any place like the market is often restricted and questioned as their husbands are not living with them. Since their husbands have migrated to India, the local administration often does not address any of their problems, and they are often deprived of governmental facilities.

Role of SHGs as coping mechanism to various vulnerabilities of the left behind women

Self-help groups (SHGs) not only play a hastening role in the life of women in Bangladesh but also have a role in the country’s economic development. A well known concept in Bangladesh, the self help groups have achieved fair success in reducing women’s vulnerability in all streams be it in reducing poverty, to induce education or to socially uplift their position. The left behind women who face many problems after their husbands’ migration have coped with problems and empowered themselves by getting involved with self-help groups.

The SHGs have moulded the lives of these left behind women for their beneficence. They have empowered the women from within by creating conditions to facilitate the real development. SHGs have been capacitated enough to make the women left behind capable of addressing their vulnerability towards HIV/AIDS and protecting themselves from any form of harassment. SHGs are also working on enhancing women’s awareness to STI and HIV/AIDS related issues with the active support of Peer Educators and Out Reached Workers of ongoing projects. Focus group discussions (FGDs) with SHG members have encouraged the community to visit the clinics for their STI/HIV related problems. This has facilitated early diagnosis and treatment of STI/HIV. SHGs have also capacitated women for seeking treatment for themselves and their children and have also developed linkages with the health care providers at these clinics and encourage their members to visit the clinics for the utilization of available services. The Left behind women are now able to address their vulnerability to HIV/AIDS and have started protecting themselves. Self help groups are emerging as a positive approach to promoting women’s empowerment, allowing left behind women to raise their voices against HIV, stigma and discrimination and violence.

The LBW are now well aware of their sexual and reproductive rights. As a result, when their husbands return to their native places, the wives negotiate the use of condoms during intercourse. LBW also refrain from sex with their husbands when they come back. They also persuade their husbands to go to Integrated Counselling and Testing Centre (ICTC) for HIV tests. The SHGs have made a significant change in the mindset of these women, simply by empowering them and making them understand their vulnerability to STI/HIV. In source communities, pre and extra-marital sex among the Bangladeshi male migrants and spouse have been prevalent and an accepted practice (Emphasis, 2011). Living away from family often impels mobile population to seek alternative support systems to satisfy needs which may lead to engagement in risky, unhealthy behaviours (Samuels and Wagle, 2011). Nowadays, with the contribution of the SHGs, inter spousal communication has increased among the LBW. Almost every second woman from the impact population mentioned that the knowledge they have gained through SHGs is also being transferred to their husbands. The women have started discussing safe sex over the phone with their husbands. LBW also impart the knowledge of various STIs and HIV/AIDS to their husband and also sometimes ask them to abstain from sex in India or to use condoms when they are engaged in sex with female sex workers.

Promoting more open dialogue and communications between spouses can also empower women and lead to more equitable conjugal relationships and engaging in less risky sexual behaviours (Samuels et al., 2014b). The collective voice of the LBW had also resulted in the decline of their men’s second marriage at the destination on the pretext of their wives’ extramarital affairs.

SHGs are being considered as a community based resource for dealing with various community based issues and conflicts, especially those relating to women. SHGs also have impacted their social position and reduced the social harassments which used to occur daily in the life of the LBW. Among the LBW, the cases of torture by in-laws, harassment by neighbours and others have been reduced significantly, and women's capacity to deal with their problems has increased manifold. The left behind women used to face severe opposition and restriction from family and society and were not allowed to go to the market or any other places, as their husbands were working elsewhere and not staying with them. SHGs have enhanced their participation in decision making and also their mobility to the market, health facilities, and other nearby areas. The stigma associated with the mobility of LBW has been eliminated. The LBW now interact freely with anybody meeting them and do not accept the norms to cover the faces in front of strangers and visitors. The SHGs have also helped these LBW in financial crisis. Several women beneficiaries reported that with the active support of SHGs, they are able to take loans or arrange money from other sources with a minimum rate of interest.

Previously, the local administration did not address the problems of LBW and often they were deprived of governmental facilities since there was no spousal support. But after becoming members of SHGs, they are now conscious of their rights and are capable of negotiating their rights with local elected bodies and government officials. Another area where SHGs have contributed is to curtail the number of marriages of minor girls, which has been a major cause of women's vulnerabilities to trafficking, sexual exploitation, and HIV/AIDS infections. They have made the women understand the risks that are associated with early marriage.

Part of SHGs success among the LBW has been possible through establishing linkages with existing public and/or private service providers to strengthen the referral system for the mobile population as well as their spouses, as part of the regional strategy of EMPHASIS irrespective of source, transit or destination.

In a nutshell, it can be said that migration of men provides some economic relief to the left behind women in Bangladesh, but the women very often pay a heavy price due to their husband’s migration. This paper throws light on the crux of the issue that migration does not always improve the socio-economic status of the left behind women in the society; rather it puts them at a greater threat of manifold vulnerabilities. In spite of that, there are a number of success stories that are associated with the capacity building of LBW through establishing SHGs in the migration dominated communities in Bangladesh. LBW's vulnerability to STI/HIV has reduced significantly due to increased knowledge, capacity building and negotiating skills for condom use with their husbands, whenever they visit the place of origin. Existing interventions in the area have been focusing on health-seeking behaviour in a larger context rather than HIV/AIDS services, especially among left behind women (LBW) of the migrants, and also providing essential services to PLHIV. That is why women's participation in the program and association with SHGs has increased significantly and has been visible during interaction with the impact population.

From reducing the LBW’s reproductive vulnerability to looking after their financial crisis, from helping them to exercise their rights in local administrative bodies to imparting knowledge of HIV/AIDS vulnerability to their husbands, SHGs have achieved a fair success. The women are now not any more ‘Left Behind’ in their lives. They have proceeded towards an empowered and enlightened future leaving behind all vulnerabilities. Their development is not superficial and has occurred from within. The SHGs have nurtured their lives and gave freedom to the left behind women. One major setback to the proper functioning of the SHGs in reducing the vulnerabilities of the LBW is less access of the husbands to empowered health and nutrition services at the destinations.

Thus addressing the vulnerability of reproductive morbidity including HIV becomes difficult among the husbands of the LBW, which on the other hand enhances their wives’ vulnerability at the source. However, SHGs have to work for and form groups within another vulnerable group of return migrants at the source. They need to be addressed more effectively by adopting a dual approach of sending them to ICTC and also linking services for them from source and destinations. As Samuels et al. (2014a) found that working in source, transit and destination sites, while challenging, is critical for achieving positive policy results. It helps migrants living with HIV to continue accessing treatment as they cross borders and also improves communication and dialogue around HIV and AIDS among migrants at the destination and between spouses by providing information, services and raising awareness about HIV and AIDS. This can, in turn also lead to less risky behaviours.

With their indispensable and influential role, the SHGs have proved to be a blessing in the lives of the LBW of Bangladesh. It has been manifested that when a single woman fails to fight, the whole group will stand and fight for her. It can be hoped that the SHGs will very soon be able to further reduce the vulnerabilities of the left behind

women by targeting the return migrants at the source and transit areas.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Anand JS (2002). Self help Groups in Empowering Women: Case study of selected SHGs and NHGs. Discussion Paper No. 38. Kerala Research Programme on Local Level Development Centre for Development Studies, Thiruvananthapuram.

|

|

|

|

Awasthi P (2014). The women left behind. India Together. Retrieved from http://indiatogether.org/wives-of-migrant-workers-women

|

|

|

|

|

Azim T, Khan SI, Haseen F, Huq NL, Henning L, Pervez MM, Chowdhury ME, Sarafian I (2008). HIV and AIDS in Bangladesh. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 3:311-324.

|

|

|

|

|

Behera S (2011). Trans-border identities; A study on the impact of Bangladeshi and Nepali migration to India. Indian Council for Research and International Economic Relations (ICRIER) Policy Series 1.

|

|

|

|

|

Bose A (2000). Demography of Himalayan villages: missing men and lonely women. Econ. Political Wkly. 35(27):2361-2381.

|

|

|

|

|

Census (2001). Data Highlights MIGRATION TABLES [D1, D1 (Appendix), D2 and D3 Tables].

|

|

|

|

|

Cruz P, Dale A (2000). Filipinos and AIDS: It could happen to you. Conveying Concerns: Media Coverage of women and HIV/AIDS. Population Reference Bureau. pp. 20-21.

|

|

|

|

|

Chatterjee S (2014). Self help Groups and Economic Empwerment of Rural Women: A case study. Int. J. Human. Soc. Sci. Res. 2(6):152-157.

|

|

|

|

|

Decosas J, Kane F, Anarfi JK, Sodji KD, Wagner HU (1995). Migration and AIDS. Lancet. 346:826-828.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Enhancing Mobile Populations' Access to HIV & AIDS Services Information and Support (EMPHASIS) (2011). On the Move (for safe mobility, better prosperity).Newsletter of EMPHASIS Funded by Care and Big lottery Fund. 3:1-7.

|

|

|

|

|

Enhancing Mobile Populations' Access to HIV & AIDS Services Information and Support (EMPHASIS) (2012). Mid Term Review Report. Funded by Care and Big lottery Fund.

|

|

|

|

|

Gupta ML, Gupta N (2006). Economic Empowerment of Women through SHGs. Kurukshetra. 54(4):23-26 .

|

|

|

|

|

Jacka T (2014). Left-behind and Vulnerable? Conceptualising Development and Older Women's Agency in Rural China. Asian Stud Rev. 38(2):186-204.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Janz NK, Becker MH (1984). The Health Belief Model: A Decade Later. Health Educ. Behav. 11(1):1-47.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Jety S (1987). Impact of male migration on rural females. Econ. Poptical Wkly. 22(44):WS47-WS53.

|

|

|

|

|

Jingzhong Y, Pan L (2011). Differentiated childhoods: Impacts of rural labor migration on left-behind children in China. J. Peasant Stud. 38(2):355-377.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Jingzhong Y (2008). Migration and Rural communities. Transcript of the SSRC-DFID-UNDP Seminar on Migration and Development: Reflecting on 30 Years of Policy in China, UNDP, China Office.

|

|

|

|

|

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) (2001). Population Mobility and AIDS: UNAIDS Technical Update. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS.

|

|

|

|

|

Khandker SR, Kharil B, Khan Z (1995). Grameen Bank: Performance and Sustainability.World Bank discussion paper 306, THE WORLD BANK, Washington DC.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Manimekalai N, Rajeswari G (2002). Grassroots Entrepreneurship through Self Help Groups (SHGs). SEDMI J. 29:2.

|

|

|

|

|

McEvoy J (2008). Male out-migration and the women left behind: A case of a small farming community in southeastern Mexico. MS Thesis, Utah State University, Logan, UT.

|

|

|

|

|

Mercer A, Khanam R, Gurley E, Azim T (2007). Sexual Risk Behavior of Married Men and Women in Bangladesh Associated With Husbands' Work Migration and Living Apart. Sex Transm Dis. 34(5): 265-273.

|

|

|

|

|

Naujoks D (2009). Emigration, Immigration and Diaspora Relations in India. Migration Information Source. Migration Policy Institute. Washington, DC. Retrieved from (www.migrationinformation.org/Profiles/display.cfm?ID=745).

|

|

|

|

|

Nguyen D (2005). The HIV/AIDS Vulnerability of Labor Out-Migrants and its Consequences on the Left-behind at the Household Level. Paper for Contribution to the Annual Meeting of Southeast Asian Studies organized by the Graduate Institute of Southeast Asian Studies of the National Chi Nan University, Taiwan.

|

|

|

|

|

Pison G, Guenno BL, Lagarde E, Enel C, Seck C (1993). Seasonal migration: A risk factor for HIV in Rural Senegal. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 6:196-200.

|

|

|

|

|

Poundel KC, Jimba M, Okumura J, Joshi AB, Wakai S (2003). Migrants' risky sexual behaviours in India and at home in far western Nepal. Trop Med and Int Health. 8:933-939.

|

|

|

|

|

Roy AK (2011). Distress Migration and 'Left Behind' Women: A study of Rural Bihar. Jaipur, India: Rawat Publications.

|

|

|

|

|

Roy AK (2003). Impact of Male outmigration on left behind women and families: A case study of Bihar. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation. International Institue for Population Sciences, Mumbai, Maharshtra, India.

|

|

|

|

|

RCAP (Rural Center for AIDS/STD Prevention) (1995). Behavior Change Models For Reducing HIV/STD Risk. Fact Sheets Number 3. A Joint Project of Indiana University, University of Kentucky and University of Wyoming. Retrieved from

View.

|

|