ABSTRACT

Due to its fragmented nature, the typically remote location of project sites and considerable reliance upon migrant workers, the construction industry in South Africa is adversely affected by the HIV/AIDS pandemic. The correct and consistent use of condoms is critical to combatting the spread of infection and reinfection. The demographic, behavioural and AIDS-related knowledge determinants of condom use at last sexual encounter were investigated in a survey of 512 site-based construction workers in the Western Cape Province. Half of all survey participants reported not having used a condom at last sexual encounter. Respondents most likely to have not used a condom were predominantly ‘Black’ African, single, in the 27 to 36 and 37 to 49 years old age groups, and those engaging in risky sexual behavior. Gender, education, employment position, alcohol consumption and cannabis (‘dagga’) use were not found to be significantly related to condom use, nor was the extent of workers’ AIDS-related knowledge. Workplace interventions by employers (in response to requests by the South African government for greater private sector involvement), whilst focusing on all employees, should concentrate their efforts on identifying and targeting those demographic sub-populations that are at greatest risk for lack of condom use. Particular attention should be given to construction workers who are migratory (rural to urban work-seekers), working on sites in remote areas, or working in environments where the appeal and likelihood of risky sexual behavior are anticipated to be greatest.

Key words: Condom use, construction workers, South Africa.

The national prevalence of HIV/AIDS in South Africa is reportedly one of the highest in the world (Simbayi et al., 2014), and has risen from 10.6% of the population (5.2 million persons) in 2008 to 12.2% (6.4 million persons) in 2012 (Shisana et al., 2014). The national prevalence varies by age, gender, race, locality type, and province. Shisana et al. (2014) reported that, overall, nearly two-thirds of respondents (65.5%) indicated that they had tested for HIV, with significantly more females (71.5%) testing than males (59%). No differences were detected in testing on the basis of race. Shisana et al. (2014) reported the engagement in antiretroviral treatment (ART) for people living with HIV (PLWH), as follows: by gender (male: 25.7%; female: 34.7%); by age (15 to 24 years: 14.3%; 25 to 49 years: 31.2%; 50+ years: 42.7%); and by race (Black African: 30.9%; ‘Other’ 41.3%). The study also found that nearly two thirds of both males and females reported having tested within the last year. In 2017, HIV-related deaths in South Africa accounted for around one quarter of all deaths (25.03%), down from 41.93% in 2002 (Statistics South Africa, 2017). This improvement in mortality outcome is largely attributed to the extensive rollout of the antiretroviral treatment (ART) in the public health system in the intervening years (Karim et al., 2009).

The country currently has the largest ART programme in the world in terms of the absolute number of persons with treatment exposure. The significant up-scaling of the national ART programme was achieved after an earlier period of considerable ‘AIDS-denialism’ by the government. Post-2008 the SA government accelerated its efforts to combat the pandemic on all fronts, including a robust prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) programme, greater availability of ART, and improved access to condoms (Karim et al., 2009; Woldesenbet et al., 2012). The condom programme saw considerable expansion in a few years. Between 2007 and 2010, the distribution of male condoms increased by 60%, from 308.5 million to 495 million a year. In the same period, the number of female condoms distributed increased from 3.6 million to 5 million (South African National AIDS Council and National Department of Health, 2012). In addition to this public sector effort, Goal 5 of the National Strategic Plan (NSP) for HIV, TB and STIs (South African National AIDS Council (SANAC), 2017) proposes “… deeper involvement of the private sector and capacitation of civil society sectors and community networks …”.

This has been elaborated into calls for the private sector to engage in workplace intervention programmes, including use of peer educators, support and capacity building, condom distribution, and antiretroviral therapy. The link between unprotected sexual intercourse and the risk of HIV infection has been clearly established (World Health Organisation, 2002), and correct and consistent condom use is pivotal to controlling the spread of HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS/UNFPA, 2004). Condom use is reported to reduce the risk of HIV transmission by between 80% (Weller and Davis, 2002) and 90% (UNAIDS, 2013). The benchmark survey research into HIV prevalence and incidence in South Africa is the South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence and Behaviour Survey, conducted jointly by the Human Sciences Research Council and the Medical Research Council (Shisana and Simbayi, 2002; Shisana et al., 2005; Shisana et al., 2009; Shisana et al., 2014). In comparing the findings emanating from four national HIV prevalence surveys in South Africa (2002, 2005, 2009, 2014), Shisana et al. (2014) noted that condom use at last sexual intercourse encounter (hereafter termed ‘condom use at last sex’) increased significantly from 2002 to 2008 in the overall population, but then decreased significantly in 2012, despite more people being aware of their HIV status.

This decrease in condom use at last sex was evident in all three age cohorts (15 to 24 years; 25 to 49 years; and 50 years and older), and for both genders except among females aged 50 years and older. There were also significant gender differences within each age cohort, with males consistently reporting higher rates of condom use at last sex than females in the period since the 2002 survey (Shisana et al., 2014). High rates of unprotected sexual intercourse (28 to 54%) have been found in surveys in the general population in South Africa (Crepaz and Marks, 2003; Olley et al., 2005). MacPhail and Campbell (2001) examined condom use by young people in a South African township and identified six factors that adversely influence condom use: low perceptions of risk; peer group norms and expectations; relative lack of condom availability (or failure to ensure appropriate availability); adult attitudes and preferences about condoms and sex; male-skewed gendered power relations; and adolescent condom affordability. Hargreaves et al. (2007) identified poor and inconsistent male condom use as a key driver of HIV infection in South Africa.

Illicit drug use and excessive use of alcohol before sexual intercourse have been found to be associated with risky lifestyles and lack of condom use (Parry et al., 2005; Kalichman et al., 2007; Peltzer et al., 2011; Seth et al., 2011). Studies relating condom use to factors such as knowledge of how to use a condom and knowledge of STI transmission (Eggers et al., 2014), and to HIV-related knowledge (Villar-Loubet et al., 2013), suggest that HIV knowledge may be an important predictor of sexually risky behaviour in the South African context (Scott-Sheldon et al., 2013). Despite being disproportionately adversely affected by the HIV/AIDS pandemic (Bureau for Economic Research (BER)/ South African Business Coalition on HIV/AIDS (SABCOHA), 2004), the construction industry was initially one of the slowest sectors to respond (Meintjes et al., 2007). A variety of factors contribute to the heightened exposure of the sector to the pandemic. Construction work is fragmented in nature and diverse in terms of location and type of work.

The industry is dominated by small firms including an informal sector about which little is known. It has comparatively low levels of worker education and literacy (especially for older workers). There is widespread use of ‘informal’ labour (even in the formal industry), and migratory workers are a prominent feature of its workforce. The temporary nature of construction projects is reflected in the lack of permanent employment status for many workers. Productivity takes priority over working conditions (Meintjes et al., 2007). Bowen et al. (2008), in a national study of 7226 construction workers, reported an estimated HIV occurrence of 13.9% in the industry, higher than that for the general population. However, little research has been conducted into condom use and risky sexual behaviours amongst construction workers. This paper reports on condom use at last sex by construction workers in terms of their demographic and lifestyle risk behaviour characteristics, and AIDS-related knowledge.

Study design and population

The study design involved a cross-sectional survey adopting a quantitative method of data analysis, and complied with the requirements of the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Engineering and the Built Environment at the University of Cape Town. Data collection involved a questionnaire administered on site. The survey participants (n=512) comprised unskilled and skilled workers and site office-based staff drawn from 6 construction companies on 18 sites in the Western Cape. The companies were selected purposively (aimed at construction workers) and on a convenience basis (by using personal contacts and contacts from previous research studies) following Leedy and Ormrod (2009). The printed questionnaire was administered in a supervised field setting to all employees present when researchers visited each construction site. Separate questionnaires were prepared in three languages: Afrikaans, English and isiXhosa (an indigenous African language); representing the most commonly spoken languages in the Western Cape region. Experts in the other two languages translated the initial English-language instrument.

On each site, with the co-operation of the respective construction company, workers were gathered together and informed about the nature of the study. They were assured that their participation was entirely voluntary and anonymous, and told that they could withdraw such participation at any time. Large offices, comprising re-used shipping containers with tables and chairs, were used for workers to complete the questionnaires in relays on each site. No incentives were offered for participation. The supervising field researchers included a female and two males proficient in all three languages. Their responsibility covered only guidance on the meaning of questions, and they were not allowed to advise participants about their answers. Male field administrators assisted male participants and the female administrator assisted female participants. Every effort was made to maintain participants’ dignity and privacy at all times. The time taken to complete the questionnaires ranged from 30 min to 1 h.

Data management

Data collection

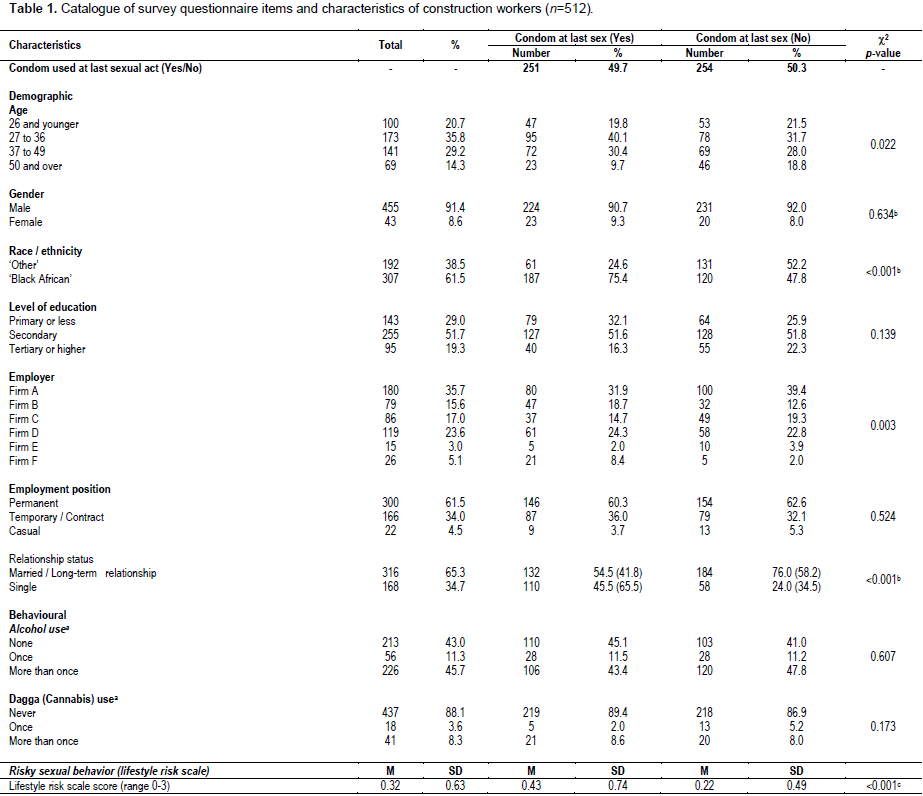

The questionnaire design was drawn from items in instruments previously used for general population surveys in South Africa by Kalichman and Simbayi (2003, 2004). Questions asked for demographic details included condom use at last sex, alcohol consumption and drug (cannabis/‘dagga’) use over the preceding 3 months, lifestyle risk behaviour within the last 3 months, and the level of AIDS-related knowledge. The catalogue of questions and scale measures is shown in Table 1.

Questionnaire items

Demographic characteristics: These cover age, gender, ethnicity, education level, employer (participating firm: anonymously labeled for analysis as A to F), employment position, and domestic relationship status. Ethnic options include: ‘Black’ African; ‘Coloured’ (mixed race); Indian; and ‘White’. These categories continue to be used in post-1994 South Africa as a measure of transformation of the economy and for employment equity purposes, and have no other connotation. For analytical reasons the latter three groups are combined as ‘Other’ in the data processing. Education is differentiated into three levels of achievement: ‘At most primary schooling’, ‘Secondary schooling’, and ‘Tertiary education or higher’. Employment status is categorized as ‘Permanent’, ‘Temporary (Contract)’, and ‘Casual’. These are the distinctions generally found in the South African construction industry. Domestic relationship status is recorded as either ‘Married or long-term relationship’ or ‘Single’.

Condom use at last sexual act: This is a dichotomous (‘yes’/’no’) question.

Substance use: Two questions are used to explore participants’ alcohol and ‘dagga’ (cannabis) use in the preceding 3 months. For each, response options are ‘never’, ‘once’, and ‘more than once’.

Variable development

Questionnaire item responses were transformed into variables for analysis; with scale measures devised for risky sexual behaviour (as a lifestyle risk) and level of AIDS-related knowledge.

Risky sexual behaviour (lifestyle risk): The scale measure for risky sexual behaviour uses three dichotomous (‘yes’/’no’) items, drawn from Kalichman and Simbayi (2003, 2004). For example, ‘Have you had 2 or more sex partners in the past 3 months?’. The scale is scored for the number of affirmative responses (thus ranging from from 0 to 3), with higher scores indicating higher levels of risky sexual behaviour.

AIDS-related knowledge: The scale measure for this variable uses seven items drawn from Carey et al. (1997) and Kalichman and Simbayi (2003, 2004). For example, ‘Must a person have many different sex partners to get AIDS?’. Response options were ‘yes’, ‘no’, or ‘don’t know’. The scale is scored for the number of correct responses (range 0 to 7), with higher scores indicating higher levels of correct AIDS-related knowledge.

Data analysis

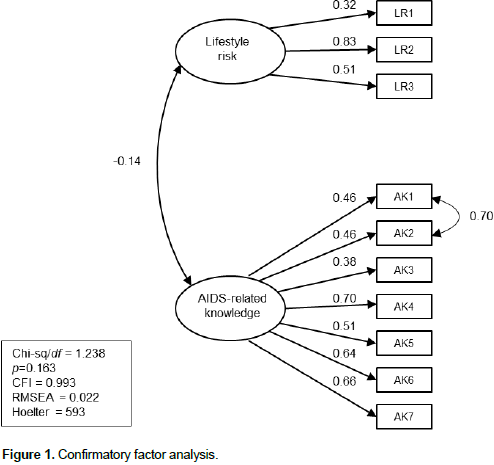

The software application IBM SPSS Ver. 24.0 for Macintosh (IBM Corporation, 2013a) was used for data analysis and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was carried out with IBM AMOS Ver. 24.0 for Windows (IBM Corporation, 2013b). Missing value analysis yielded less than 5% missing values, with most items having less than 2%. This meant that listwise deletion of cases with missing values was appropriate (Graham, 2012). CFA covered the lifestyle risk and AIDS-related knowledge scale measures. Four critical fit indices (Kline, 2011) determined the degree of fit of the measurement model (with index values reflecting good model fit indicated in parenthesis): χ2/df ratio (less than 4); comparative fit index (CFI of 0.95 and greater); root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA 0.06 and less); and Hoelter critical N (CN index 200 and greater). Model improvements and parsimony were tested using the Chi-square difference test (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2014).

Descriptive statistics explored respondent characteristics in relation to condom use at last sex (Table 1). Bivariate analysis examined the relationship between condom use at last sex and demographic and behavioural factors, and AIDS-knowledge (Table 1). Multivariate logistic regression was used to explore the simultaneous association of multiple factors with condom use at last sex (Tables 2 and 3). For the categorical explanatory variables in the logistic regression, the reference categories were: age (50 years and older), gender (female), ethnicity (‘Other’), education (tertiary or higher), firm (Firm F), employment position (permanent), relationship status (married or in a long-term relationship), and substance abuse (not having used alcohol or ‘dagga’ in the last 3 months). For the dependent variable the reference category was ‘condom not used at last sex’. Thus the odds of workers having used a condom at last sex, rather than not having used one, were examined as a function of the different categories of their demographic characteristics, lifestyle and AIDS-related knowledge scores.

Participant characteristics

Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1. Most participants were male (91%; n = 461) and between 18 and 69 years old (mean = 36, SD = 10.86), with most respondents in the 27 to 36 year age group (36%; n = 168). Almost two-thirds (62%; n = 313) were “Black” African. Primary education was the highest level for 29% (n = 144), whilst 52% (n = 260) had secondary level education. Sixty-two percent (n = 304) of participants were permanent employees; 34% (n = 167) were on a contract (project) basis; and 4% (n = 22) were casually hired workers. Nearly two thirds of all respondents (65%; n = 320) were either married or in long-term relationships. Ten percent (n = 34) reported being HIV +. Overall, 50% (n = 251) of survey participants had used a condom at last sex. In terms of relationship status, 66% (n = 110) of single participants reported condom use at last sex compared to 42% (n = 132) of participants who were either married or in a long-term relationship. Of all survey participants, 57% had consumed alcohol at least once during the preceding 3 months and 12% had smoked cannabis (‘dagga’) at least once over the same period. For the lifestyle risk scale measure, the overall mean score was M = 0.32 (SD = 0.63) and for the AIDS-related knowledge measure the overall mean score was M = 4.81 (SD = 2.02).

Confirmatory factor analysis

No correlated errors were specified in the initial measurement model. Output indices indicated a poor fit to the data (χ2 /df ratio = 8.538, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.765, RMSEA = 0.121, and Hoelter (95%) = 86). All factor loadings were statistically significant (p < 0.001). However, the modification indices indicated the need for correlated error terms of AK1 (‘Can men give AIDS to women?’) with AK2 (‘Can women give AIDS to men?’). With this path specified, the resultant model presented an excellent fit to the data (χ2 /df ratio = 1.238, p = 0.163, CFI = 0.993, RMSEA = 0.022 (90%: LO = 0.000; HI = 0.041), and Hoelter (95%) = 593), with all factor loadings statistically significant (p < 0.001) (Figure 1).

Bivariate tests of association

Bivariate tests of association were used to explore the relationship between condom use at last sex with each of the demographic variables, and with alcohol consumption and ‘dagga’ use (Table 1). Condom use at last sex was significantly associated with age, [ï£2 (3, n = 483) = 9.597); p < 0.05], ethnicity [ï£2 (1, n = 499) = 40.126); p < 0.001], employer organisation [ï£2 (5, n = 505) = 18.316); p < 0.01], and domestic relationship status [ï£2 (1, n = 484) = 24.652; p < 0.001]; but not significantly associated with gender or education (Table 1). Having had two or more sex partners in the last three months was significantly associated with age [ï£2 (3, n = 485) = 10.417); p < 0.05], with proportionately more workers in the 26 years and younger age group reporting having had two or more sex partners in the last three months compared to workers in the other age groups. An independent samples t-test indicated a significant difference in lifestyle risk scores for those using a condom at last sex (M = 0.43; SD = 0.74) as compared to those who did not (M = 0.22; SD = 0.49), indicating that those who reported greater risky sexual behaviour are more likely to use a condom; t = (427) = -3.76; p < 0.001). No significant differences were found in the t-test for mean levels of AIDS-related knowledge.

Proportionately more adults in the 27 to 36 and 37 to 49 year old age groups, ‘Black’ African workers, workers who were single, and workers engaging in more risky lifestyles, reported using a condom at last sexual encounter, than did survey participants in other demographic categories. With regard to employer organisations, the proportions of workers who reported having used a condom at last sex were significantly different (Table 1), suggesting that some firms were more rigorous or consistent in their promotion of safer sex (probably through greater provision of free condoms). A one-way ANOVA conducted to explore the impact of age on levels of lifestyle risk and AIDS-related knowledge indicated a statistically significant difference in the lifestyle risk scores for the four age groups, F (3, 483) = 3.74, p < 0.05. Post hoc comparisons using the Tukey HSD test indicated that the mean score in respect of lifestyle risk for workers 50 years and older (M = 0.14; SD = 0.39) was significantly lower than that of workers in the youngest cohort (M = 0.45; SD = 0.66).

The 27 to 36 years (M = 0.35; SD = 0.67) and 37 to 49 years (M = 0.27; SD = 0.61) groups did not differ significantly from either the youngest or the oldest cohorts. For AIDS-related knowledge, there was a statistically significant difference in the AIDS-related knowledge scores for the four age groups, F (3, 469) = 4.13, p < 0.01. Post hoc comparisons indicated that the mean score in respect of AIDS-related knowledge for workers 50 years and older (M = 4.23; SD = 1.83) was significantly lower than that of workers in the youngest <26 year old group (M = 5.34; SD = 1.77). The 27 to 36 year old (M = 4.76; SD = 2.11) and 37 to 49 year old (M = 4.78; SD = 2.10) groups again did not differ significantly from either the youngest or the oldest cohorts. In essence, the youngest workers reported engaging in the riskiest lifestyles, displayed the highest levels of AIDS-related knowledge, and reported having proportionately more sex partners in the preceding 3 months than all other age groups.

However, proportionately more adults in the 27 to 36 and 37 to 49 year old age groups reported condom use at last sex compared to the workers in the youngest and oldest groups. ‘Black’ workers had significantly lower levels of AIDS-related knowledge (M = 4.23; SD = 2.10) than workers in the combined ‘Other’ ethnic category (M = 5.70, SD = 1.51); t = (475) = 8.92; p < 0.001), but there was no significant difference in lifestyle risk scores between the two groups. Female workers reported significantly lower levels of lifestyle risk (M = 0.07; SD = 0.26) than male workers (M = 0.34, SD = 0.64); t = (102) = 5.47; p < 0.001). They also displayed significantly higher levels of education than male participants [c2 (2, n = 497) = 30.095; p < 0.001] and significantly higher levels of AIDS-related knowledge (M = 5.61; SD = 1.78) than males (M = 4.75, SD = 2.02); t = (55) = -3.03; p < 0.01).

Multivariate analysis

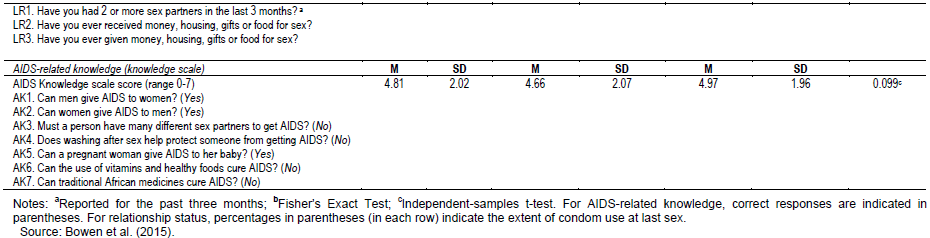

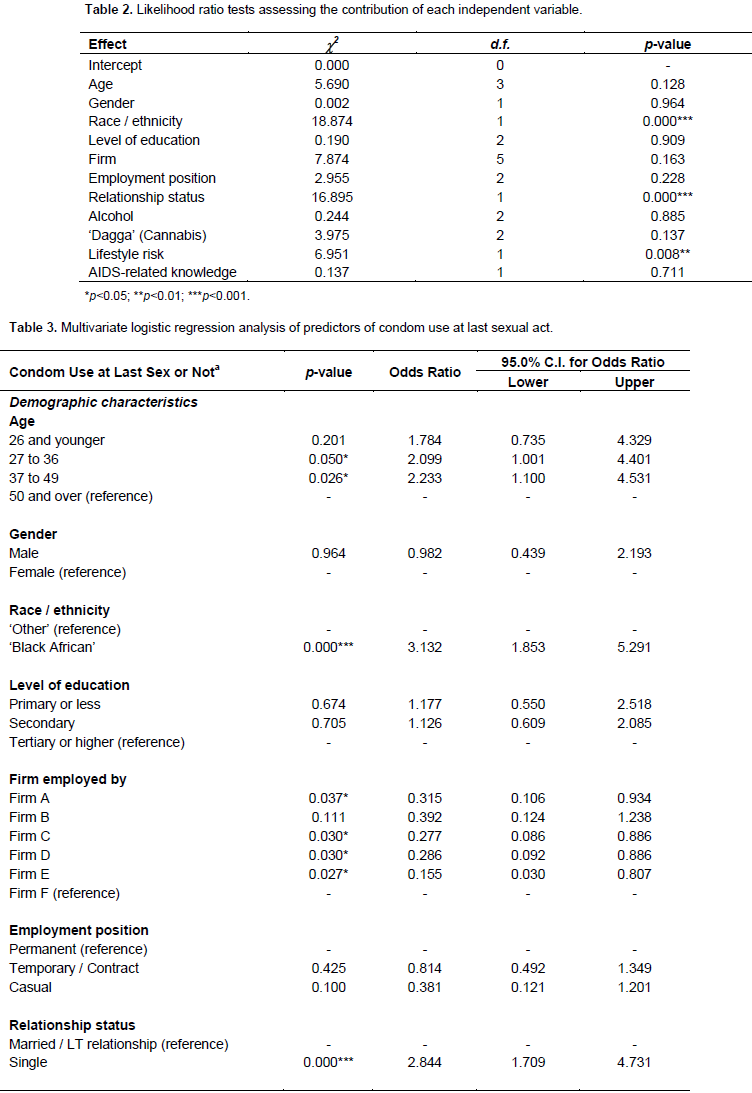

Multivariate logistic regression was used to explore the factors associated with condom use at last sex. Table 2 shows the likelihood ratio tests for assessing the contribution of each independent variable to the prediction of condom use at last sex and this test evaluates the overall relationship between an independent variable and the dependent variable, providing an indication of the unique contribution of each independent variable to the prediction of condom use at last sex. Statistically significant unique contributions were made by ethnicity (χ2 = 18.874, p < 0.001), relationship status (χ2 = 16.895, p < 0.001), and lifestyle risk (χ2 = 6.951, p < 0.01). None of the age, gender, education level, employer organisation, alcohol consumption, and ‘dagga’ use factors made uniquely statistically significant contributions to the prediction of condom use at last sex. A test of the full model against a constant-only model was statistically significant, indicating that the predictors (as a set) reliably distinguished between workers who used a condom at last sex and those who did not (χ2 = 83.837, p < 0.001 with df = 21). Details of the multivariate logistic regression analysis are depicted in Table 3.

When compared with workers aged 50 years or more, workers in the 27 to 36 age group were 2.1 times more likely to have used a condom at last sex (aOR = 2.10; 95% CI: 1.00-4.40). Similarly, workers 37 to 49 years of age were 2.2 times more likely than those 50 years or older to have used a condom (aOR = 2.23; 95% CI: 1.10-4.53). No significant difference in condom use at last sex was found between workers younger than 26 years and those 50 years and older. Both the youngest and the oldest age categories reflected lower use of condoms at last sex than did the two intervening age groups. In other words, construction workers 26 years and younger were as likely not to have used a condom at last sex as those in the 50 years and older age category. Although female construction workers reported marginally greater use of condoms at last sex than did their male colleagues, the difference was not significant. ‘Black’ construction workers differed significantly from workers in the combined ‘Other’ ethnic group regarding condom use at last sex (p < 0.001), with ‘Black’ workers being 3.1 times more likely than workers in the ‘Other’ group to have used a condom at last sex (aOR =3.13; 95% CI: 1.85-5.29).

In comparison with workers in Firm F [the firm considered to represent best practice in HIV/AIDS intervention management amongst those surveyed (Bowen et al., 2014)], workers in some other firms were significantly less likely to have used a condom at last sex. The comparisons are: Firm A (69% less likely); Firm C (72% less likely); Firm D (71% less likely) and Firm E (85% less likely). Although condom use at last sex by workers in Firm B was lower than that exhibited by workers in Firm F, the difference was not significant. When Firm B [a firm also considered to be proactive in HIV intervention management (Bowen et al., 2014)] was designated as the reference category, workers in all firms other than Firm F reported lower use of condoms at last sex, but not significantly so. In comparison to workers in Firm B, workers in Firm F reported much higher use of condoms at last sex (2.5 times), but the difference was not significant. Firm D is one of the largest firms participating in the survey and Firm E is the smallest, in terms of both number of employees and annual turnover value.

Thus, although firm size was not directly entered into the predictive model, these results suggest that workers’ condom use at last sex does not relate to firm size, but may be associated with the quality of the construction firm’s HIV/AIDS intervention management. In terms of relationship status, single workers were almost three times more likely than those who were married or in long-term relationships to have used a condom at last sex than not to have used one (aOR = 2.84; 95% CI: 1.71-4.73). Construction workers engaging in greater levels of lifestyle risk were almost twice as likely to have used a condom at last sex than not to have used one (aOR = 1.65; 95% CI: 1.13-2.43). This suggests that workers may be aware of their risky lifestyles and take appropriate precautionary measures. To summarize, the multivariate model indicated that the following were significant in predicting greater likelihood of condom use at last sex: being 27 to 49 years old, ‘Black’ African, employed by Firm F, single, and engaging in risky sexual behavior. Gender, level of education, nature of employment, alcohol consumption, ‘dagga’ use, and AIDS-related knowledge were not found to be significant in the multivariate model.

About half of the survey participants reported condom use at last sex, exceeding the 36% condom use at last sex findings in the general population by Shisana et al. (2014). The two studies differ significantly in their sampling design - the general population figures are derived from a national probability sample while the current figures are drawn from a purposive convenience sample in only one industry sector based in a single region of the country. Accordingly, it is difficult to directly compare the two figures on condom use, though the rates observed in this study are promising for the sector. The inter-firm comparisons of workers’ use of condoms at last sex suggest that more vigorous safe sex campaigns may substantially improve condom practice among employees and be effective in combating the spread of HIV infection. Demographic and behavioural factors, but not AIDS-related knowledge, are associated with construction workers’ condom use at last sex. Specifically, construction workers in the 27 to 36, and 37 to 49 year age groups, ‘Black’ African workers, single workers, and those engaging in risky sexual behaviour, are significantly more likely to have used a condom at last sex than other workers.

Significant differences were found in the extent of condom use at last sex between ‘Black’ African workers and the ‘Other’ combined ethnic group. This finding is consistent with that of Simbayi et al. (2014), who noted that ‘Black’ Africans constitute the largest racial grouping nationally and have an HIV prevalence rate 17 times higher than that of both ‘Whites’ and Indians Condom use at last sex by workers employed in Firm F was significantly higher in comparison to workers in all other firms, with the exception of Firm B. This finding aligns with the qualitative study by Bowen et al. (2014) of 12 construction firms in the Western Cape where it was found that Firms B and F employed more comprehensive HIV/AIDS interventions for their workers than did the other firms, and exhibited more active involvement by senior management. The importance of this “championing” role cannot be understated. With respect to domestic relationships, single construction workers were almost three times as likely as workers who were married or in a long-term relationship to have used a condom at last sex. They also reported having had proportionately more sex partners in the previous 3 months, compared to workers in more committed relationships.

These findings broadly align with Shisana et al. (2014), who reported that higher percentages of condom use at last sex were found in all age groups among those who were single compared to those who were married or in civil unions. Similarly, it was found that construction workers engaging in more risky sexual behaviour (multiple sex partners and transactional sex) were almost twice as likely to have used a condom at last sex, than were workers whose reported lifestyles were more risk averse. Workers engaging in risky sexual behaviour thus appear to be aware of the dangers thereof and are taking appropriate precautions. No significantly strong association was found among the construction workers in our survey between condom use at last sex and their gender, education, and employment position alcohol consumption and ‘dagga’ usage. Regarding alcohol and drug use, a possible explanation may be under-reporting of such use, given the low tolerance of construction firms to such behaviour, the dangerous nature of construction work, and the widespread use of mechanical equipment and hand-tools on construction sites. Construction safety messages may be delivering their intended effect here.

With regard to AIDS-related knowledge, Simbayi et al. (2014) also reported a lack of association between AIDS-knowledge and condom use. It is possible that the effect of awareness and prevention campaigns is beginning to diminish, and greater effort is needed to refresh the relevant messages. While we found that less secure employment was linked to lower levels of condom use at last sex, the difference in employment position is not significant in this regard. A key finding of this study is that the higher risk categories of construction workers are those most likely to use condoms regularly, namely: workers 27 to 49 years old, ‘Black’ African, single, engaging in risky sexual behavior, and employed by companies more actively engaged in HIV/AIDS intervention management. Another key finding is that the youngest construction worker age group is not revealed as a high-risk category, at least not in terms of condom use at last sex. This contrasts with the testing behaviour of the same sample of construction workers, whereby Bowen et al. (2015) found that workers 20 years and younger were the least likely (46%) of any age group to have been tested, and Shisana et al. (2014) found similar results (51%) in relation to the general population. Our finding with regard to construction workers’ condom use at last sex and age categories is thus at odds with the national study and requires further investigation employing a larger sample size of construction workers across a greater geographical area.

Using multivariate logistic regression analysis, this study examined the relationship between the demographic characteristics of construction workers, their lifestyle risk behavior, their AIDS-related knowledge, and their use of condoms at last sex. It was found that: (1) age, ethnicity, firm, relationship status, and lifestyle risk all predict condom use at last sex; (2) gender, level of education, employment position, alcohol consumption and drug use, and level of AIDS-related knowledge are not determinants of regular condom use; (3) workers aged 26 years and younger and workers aged 50 years and older are the least likely to use condoms regularly; (4) ‘Black’ African workers are the most likely to use condoms regularly; (5) single workers, as opposed to workers who are either married or in long-term relationships, are the most likely to use condoms regularly; (6) workers engaged in risky sexual behavior are almost twice as likely to use condoms regularly as those less so engaged; and (7) workers employed by companies with comparatively more proactive HIV/AIDS intervention management are more likely than workers in less proactive firms to use condoms regularly.

These findings provide pointers for better proactive intervention by construction organizations, indicating that a more differentiated and nuanced approach to AIDS awareness and prevention campaigns should be adopted. Sub-groups, rather than the entire industry workforce, may be considered higher risk in terms of inconsistent condom use. Awareness and prevention campaigns should target all workers irrespective of age, but be mindful that workers in the 27 to 49 year age range are particularly at higher risk, even if they exhibit greater condom use. Workers should be encouraged to use condoms correctly and consistently. Regular and specific attention should be paid to this, through the use of visual media and demonstration models, in all campaigns. Attention needs to be given to the reasons why workers 26 years and younger are comparatively less inclined than their older (27 to 49 years) colleagues to regularly use condoms, especially given their lifestyle risk behavior and more frequent sexual partners.

For example, what roles do norms, peer group influence, condom affordability and availability, and male-gendered power relations play in this decision? All of these may indicate how campaigns can be more nuanced. HIV/AIDS workplace awareness and prevention campaigns, and peer educator training, should pay closer attention to age, ethnicity, and relationship status to positively influence more regular condom use. The location of sites and the use of migrant labour within the industry has been noted as exacerbating the spread of AIDS, but these factors were not directly investigated in our study. The nature of migrant employment, and the remoteness of many project sites in South Africa, places workers in conditions that tend to promote poor lifestyle behaviours, thus increasing their risk of contracting HIV while (in the case of remote sites) also removing them from the proximity of appropriate health care facilities.

Workers who are separated from their families for long periods of time, may become prone to using sex workers or having multiple sexual partners, become HIV-positive, and then return to their primary sexual partners to spread the virus in their home communities. Construction organizations thus need to tailor awareness and prevention messages specifically for migrant workers and employees working on remote sites. This study has shown that, while the condom use behaviours of construction workers are not directly comparable to those in the general population, campaigns and interventions relating to the effectiveness of condom use in combating the spread of HIV/AIDS can be improved among construction companies. This should not be difficult in the formal sector, given appropriate senior management commitment and support. However, reaching into the informal sector of the South African construction industry will be a far more formidable task.

Limitations

The companies involved in our study are representative of construction firms operating in the Western Cape province of South Africa. However, some are also active in other provinces, and would use similar voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) services for HIV/AIDS. The cross-sectional nature of the survey; the reliance on participants’ self-declarations (including possible recall and social desirability bias); and the potential under-reporting of risky behaviours, are all limitations. Condom use was only measured for the last sex act and does not account for respondents’ attitudes towards condoms nor the consistency or correctness of condom use. Moreover, it did not explore the exact nature of condom use by workers who were married or in long-term relationships, nor any differences between them. These aspects required further investigation. Our investigation used a self-reporting survey instrument. There is a potential risk of common method variance and thus data validity. Method variance is attributable to the measurement method rather than to the construct(s) of interest.

Common method biases arise from having a common respondent, a common measurement context, a common item context, or from the characteristics of the items themselves. The potential problem of common method variance is embedded in questionnaire survey research design. With self-reporting survey instruments such as this one, an issue of response validity arises, particularly with respect to the education level of survey respondents – nearly 30% of the participating construction workers had achieved at most only primary level education. Regardless of the questionnaire language chosen by participants, and regardless of the assistance available from the attending field researchers, the dichotomous and multiple choice tick-box format of the questions may have led some of the more illiterate construction workers to mask their disadvantage by completing the questionnaire on a more or less random basis - a simple subterfuge if pride or potential loss of face would have prevented such participants from seeking help with understanding the questions and answer options.

The authors reported no potential conflicts of interest.

The authors wish to express their appreciation to the South African Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) for permitting them to draw on relevant HSRC questionnaires in the compilation of the survey questionnaire employed in this study. This work is based on research supported by the National Research Foundation of South Africa under Grant (UID) 85376. The Grantholder acknowledges that opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in any publication generated by the NRF supported research are those of the authors, and that the NRF accepts no liability whatsoever in this regard.

REFERENCES

|

Bowen PA, Allen Y, Edwards PJ, Cattell KS, Simbayi LC (2014). Guidelines for effective workplace HIV/AIDS intervention Management by construction firms. Constr. Manag. Econ. 32(4):62-81.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Bowen PA, Dorrington R, Distiller G, Lake H, Besesar S (2008). HIV/AIDS in the South African construction industry: an empirical study. Constr. Manag. Econ. 26(8):827-839.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bowen PA, Govender R, Edwards PJ, Cattell KS (2015). Tested or Not? - A categorical examination of HIV/AIDS testing among workers in the South African construction industry. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 141:12.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bureau for Economic Research / South African Business Coalition on HIV/AIDS (2004). The Economic Impact of HIV/AIDS on Business in South Africa, 2003. Stellenbosch, South Africa: Bureau for Economic Research.

|

|

|

|

|

Carey MP, Morrison-Beedy D, Johnson BT (1997). The HIV-Knowledge Questionnaire: Development and evaluation of a reliable, valid, and practical self-administered questionnaire. AIDS Behav. 1(1):61-74.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Crepaz N, Marks G (2003). Serostatus disclosure, sexual communication and safer sex in HIV-positive men. AIDS Care 15(3):379-387.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Eggers SM, Aaro LE, Bos AE, Mathews C, de Vries H (2014). Predicting condom use in South Africa: A test of two integrative models. AIDS Behav. 18(1):135-145.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Graham J (2012). Missing Data: Analysis and Design. New York: Spinrger. pp. 3-46.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hargreaves JR, Bonell CP, Morison LA, Kim JC, Phetla G, Porter JD, Watts C, Pronyk PM (2007). Explaining continued high HIV prevalence in South Africa: Socioeconomic factors, HIV incidence and sexual behaviour change among a rural cohort, 2001-2004. AIDS 21(Suppl 7):S39-S48.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

IBM Corporation (2013a). IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh, Version 24. Armonk, New York: IBM Corp. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

IBM Corporation (2013b). IBM AMOS for Windows, Version 24. Armonk, New York: IBM Corp. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC (2003). HIV testing attitudes, AIDS stigma, and voluntary HIV counseling and testing in a black township in Cape Town, South Africa. Sex. Trans. Infect. 79(6):442-447.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC (2004). Traditional beliefs about the cause of AIDS and AIDS-related stigma in South Africa. AIDS Care 16(5):572-580.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Vermaak R, Cain D, Jooste S, Peltzer K (2007). HIV/AIDS risk reduction counseling for alcohol using sexually transmitted infections clinic patients in Cape Town, South Africa. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 44(5):594-600.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kline RB (2011). Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling (Third Edition). New York: Guildford Press. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Karim SSA, Churchyard GJ, Karim QA, Lawn SD (2009). HIV infection and tuberculosis in South Africa: an urgent need to escalate the public health response. Lancet 374(9693):921-933.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Leedy PD, Ormrod JE (2005). Practical Research: Planning and Design (Eighth Edition). New Jersey: Pearson Education. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

MacPhail C, Campbell C (2001). 'I think condoms are good but, aai, I hate those things': condom use among adolescents and young people in a Southern African township. Soc. Sci. Med. 52(11):1613-1627.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Meintjes I, Bowen PA, Root D (2007). HIV/AIDS in the South African construction industry: understanding the HIV/AIDS discourse for a sector specific response. Constr. Manag. Econ. 25(3):255-266.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Olley BO, Seedat S, Gxamza F, Reuter H, Stein DJ (2005). Determinants of unprotected sex among HIV-positive patients in South Africa. AIDS Care 17(1):1-9.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Parry CD, Plüddemann A, Steyn K, Bradshaw D, Norman R, Laubscher R (2005). Alcohol use in South Africa: Findings from the first demographic and health survey (1998). J. Stud. Alcohol 66(1):91-97.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Peltzer K, Davids A, Njuho P (2011). Alcohol use and problem drinking in South Africa: findings from a national population-based survey. Afr. J. Psych. 14(1):30-37.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Carey MP, Carey KB, Cain D, Simbayi LC, Mehlomakhulu V, Kalichman S (2013). HIV testing is associated with increased knowledge and reductions in sexual risk behaviours among men in Cape Town, South Africa. Afr. J. AIDS Res. 12(4):195-201.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Seth P, Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, Robinson LS (2011). Alcohol use as a marker for risky sexual behaviors and biologically confirmed sexually transmitted infections among young adult African-American women. Womens Health Issues 21(2):130-135.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi LC, Parker W, Zuma K, Bhana A, Connolly C, Jooste S, Pillay V, SABSSM II Implementation Team (2005). South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence, Behaviour and Communication Survey. Cape Town: HSRC Press.

|

|

|

|

|

Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi LC, Zuma K, Jooste S, Pillay-van-Wyk V, Mbelle N, Van Zyl J, Parker W, Zungu NP, Pezi S, SABSSM III Implementation Team (2009). South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence, Behaviour and Communication Survey 2008: A turning tide among teenagers? Cape Town: HSRC Press. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi LC, Zuma K, Jooste S, Zungu N, Labadarios D, Onoya D, SABSSM IV Implementation Team (2014). South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence and Behaviour Survey 2012. Cape Town: HSRC Press. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Shisana O, Simbayi LC (2002). Nelson Mandela / HSRC Study of HIV/AIDS: South African National HIV Prevalence, Behavioral Risks and Mass Media, Household Survey 2002. Cape Town: HSRC Press. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Simbayi LC, Matseke G, Wabiri N, Ncitakalo N, Banyini M, Tabane C, Tshebetshebe D (2014). Covariates of condom use in South Africa: findings from a national population-based survey in 2008. AIDS Care 26(10):1263-1269.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

South African National AIDS Council (2017). South African national strategic plan on HIV, TB and STIs 2017–2022. Draft 1.0, NSP Steering Committee Review, 30 Jan 2017. Pretoria: SANAC. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

South African National AIDS Council and National Department of Health (2012). Global AIDS response progress report 2012: Republic of South Africa. Pretoria: Government Printer. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Statistics South Africa (2017). 2017 Mid-year Population Estimates, Statistical Release, P0302, July 2017. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Tabachnick GG, Fidell, LS (2014). Using Multivariate Statistics, Pearson New International Edition. Boston: Pearson Education. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

UNAIDS (2013). UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic 2013. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS.

|

|

|

|

|

UNAIDS/UNFPA (2004). Making Condoms Work for HIV Prevention. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Villar-Loubet OM, Cook R, Chakhtoura N, Peltzer K, Weiss SM, Shikwane ME, Jones DL (2013). HIV knowledge and sexual risk behavior among pregnant couples in South Africa: the PartnerPlus project. AIDS Behav. 17(2):479-487.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Weller S, Davis K (2002). Condom effectiveness in reducing heterosexual HIV transmission. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2002: CD003255. In National HIV and AIDS and STIs Strategic Plan for South Africa 2007-2011 (2007). Pretoria; South African National Government. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Woldesenbet S, Goga AE, Jackson DJ for the SA EID study group (2012). The South African Programme to Prevent Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV (PMTCT): Evaluation of Systems for Early Infant Diagnosis in Primary Health Care Facilities in South Africa: Report on Results of a Situational Assessment, 2010. Cape Town: South African Medical Research Council. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

World Health Organization (2002). World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available at:

View

|

|