ABSTRACT

Copper oxide (CuO) nanoparticles are of incredible interest because of its efficacious applications including electronic devices, optoelectronic devices, such as microelectromechanical frameworks, field effect transistors, electrochemical cells, gas sensors, magnetic storage media, sun-powered cells, field emitters and nanodevices (for catalysis and medical applications). Examination by Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) revealed that CuO nanoparticles depicted as wire-like nature with an average size of 27 nm. The results of the particle size analyzer showed the hydrodynamic diameter of chemically syntheized CuO nanoparticles was 82.24 nm with polydisperisty index (PDI) of 0.426. The zeta potential of prepared CuO nanoparticles was -4.69 mV. After 24 h of incubation, CuO nanoparticles produced deformation in the erythrocytes, the deformation enhanced at the most elevated concentration of CuO nanoparticles (400 ppm) suspended phosphate buffer saline (PBS)/citrate; erythrocytes influence was time and dose-dependent. The results of the toxicity study shows that the red blood cell count is substantially reduced after 24 h of incubation and progressively transparnent with a concentration of 400 ppm CuO nanoparticles, when compared with negative control and positive control samples. The prothrombin time (PT) and partial thromboplastin time (PTT) test cannot be detected, which means that CuO nanoparticles appear as potent inhibitors anti-partial thromboplastin time (APTT) agents by retarding clotting time in PT and PTT test. After 24-h incubation with CuO nanoparticles, there was a substantial decrease in the platelets (PLT) count in blood sample relative to negative control and positive control samples. The exposure to CuO nanoparticles should be minimized.

Key words: CuO nanoparticles, toxicity, human blood, prothrombin time.

The study of “Nanotechnology” includes the tailoring of materials at an atomic level to accomplish unique properties that can be appropriately influenced for the desired applications (Jadhav et al., 2011; Gleiter, 2000). Materials with nanoscopic measurements not only contain possible technological applications in zones, for example, device technology and drug delivery, but are also of vital interest in that the properties of a material can alter in this transitional regime between the bulk and molecular scales (Martin, 1994). Metals of silver, zinc, copper and iron nanoparticles were eco-friendly synthesized using the method reported by Pattanayak and Nayak (2013) with a slight modifcation. Nanoparticles clinical applications is one of the most attractive areas of science nowadays, nanoparticles are used for bioremediation of diverse contaminants, water treatment, antimicrobial applications and drug delivery. Due to their essential role in the blood and systemic homeostasis, red blood cells can be considered as a landmark in any health evaluation of all NP compounds (Iancu et al., 2009; Mocan et al., 2011; Ilie et al., 2013).

Unlike metal particles, oxide nanoparticles exhibit expansion in their lattice parameters relative to their bulk parameter (Rao et al., 2004). Often, because of their small size and high density of corner or edge surface sites, they may exhibit unusual physical and chemical properties (Rodríguez et al., 2007; Ayyub et al., 1995). Both the oxidation processes and size reduction form the essential structures that transcribe a nanostructured oxide’s behavior (Sun, 2003). Copper oxide (CuO) is a semi-conducting, monoclinically formed compound. CuO is the simplest member of the copper family and has a variety of potentially useful physical properties like high temperature superconductivity, electron correlation effects, and spin dynamics (Ren et al., 2009).

The high toxicity of CuO particles resulting in nearly 100% cell death after 18 h may be a response to DNA damage as a means of preventing mutagenic results (Gurr et al., 2005). Another possibility is that the CuO nanoparticles release Cu2+ ions. An eco-toxicological analysis revealed that CuO nanoparticles were mostly toxic by soluble Cu2+ ions (Heinlaan et al., 2008), whereas another study concluded that the dissolution of Cu2+ nanoparticles was insufficient to clarify the toxicity (Griffitt et al., 2007). While limited surveys have focused on the effects of copper oxide nanoparticles on the blood parameters of different species of fish, this resulted to changes in hematological and biochemical parameters (Jahanbakhshi et al., 2015). The need of this work is to study the toxicity of CuO nanoparticle on human blood.

The objective of this study was to investigate the effects of different dosage of copper oxide nanoparticles on some hematological parameters of human blood.

The present study was carried out in the following sequence:

(1) The synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles by chemical precipitation method according to Suleiman et al. (2015).

(2) Copper sulfate 5-hydrate (CuSO4.5H2O) (Sigma Aldrich).

(3) Sodium hydroxide (1 NaOH) (Sigma Aldrich).

(i) A 0.4 M aqueous solution of copper sulfate (1.00 g copper sulfate in 10ml deionized water)

(ii) 2.0 M aqueous solutions of sodium hydroxide (NaOH) were prepared in distilled water (1.25 g NaOH in 10 ml distilled water).

(iii) Then, the solution of copper sulfate was heated to 85°C and kept under constant stirring using magnetic stirrer till complete dissolving of the copper sulfate.

(iv) After 15 min, sodium hydroxide solution (2.0 M) was added, black precipitate was formed Cu(OH)2.

(v) This precipitate was filtered out and washed with distilled water and ethanol several times alternatively to remove the impurities.

(vi) After washing the precipitate was kept in an oven at 200°C for 3 h. During this process all copper hydroxide was converted to copper oxide.

Characterization of CuO nanoparticles

The prepared CuO nanoparticles were characterized using Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) (JEOL-100 CX), X-ray Diffraction (XRD) (Shimadzu, XRD-7000, Maxima, Japan), Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) (Bruker, Tensor 37 FT-IR), and Zeta size (Malvern, UK).

The synthesis of CuO nanoparticles suspensions

Stock suspensions of CuO nanoparticles were dispersed in a mixture of dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) and PBS/Citrate (10 ml DMSO+15 ml PBS/Citrate). The mixture was sonicated using bath sonicator (Ultrasonic cleaner, Sonica, Soltec, Italy) until the particles were completely dispersed in the solution. Different concentrations of CuO nanoparticles (50, 100, 200, and 400 ppm) by adding 8 mg of CuO nanoparticles to 100 ml of the stock solution, and then diluted this solution to the other concentration, by the addition of distilled water. The procedure was carried out at The research laboratory, Pharos University, Alexandria.

Study of the effect of CuO nanoparticle on red blood cells (RBCs)

Separate erythrocytes at 37°C were washed with PBS/Citrate by centrifugation at 150 g and 37°C for 10 min. Washed erythrocytes were aliquotted into equal parts of 50 μl. CuO nanoparticles with different concentrations (50, 100, 200, and 400 ppm) suspended in PBS/citrate with DMSO (or PBS-citrate with DMSO alone for the positive control) were added to aliquot in a volume/volume (v/v) ratio of 2:1 for erythrocyte. Samples were incubated at 37°C for different periods (1/2, 3, and 24 h). Samples were tested for RBCs count after incubation periods and examined using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), Phase Contrast Microscopy (PCM), and Osmotic Fragility Measurements (OFM).

Determination of RBCs count

The RBCs samples were analyzed after incubation of blood samples in an incubator (Incubator, BTC, Egypt) at 37°C for (1/2, 3, and 24 h) using automated hematology analyzer (Sysmex, XT-1800i, Japan) at The Hematology Laboratory at Hematology Department, Medical Research Institute, Alexandria University.

Examination of CuO nanoparticles using Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

(1) After the incubation period (1/2, 3, and 24 h), RBCs samples were fixed in 1% glutaraldehyde.

(2) Fixed samples were washed by exchanging supernatant with citrated Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS) and incubated for 20 min at room temperature.

(3) This procedure was repeated four times, while the last incubation was performed overnight at 4°C.

(4) Samples of RBCs were then post-fixed for 60 min at 4°C in 1% OsO4 dissolved in PBS.

(5) Dehydrated in a graded series of alcohol/water (10%-100% v/v), critical-point dried, gold-sputtered, and examined using a scanning electron microscope (JEOL. JSM 5300 LA, Japan) at Electronic Microscope Unit, Faculty of Science, Alexandria University.

Osmotic fragility measurements were done according to Hobbie and Roth (2006).

Study of the effect of CuO nanoparticles on platelet-rich plasma

Washed platelet-rich plasma was aliquotted into equal parts of 200 μl each. CuO nanoparticles with different concentrations (50, 100, 200, 400 ppm) suspended in PBS/citrate with DMSO (or PBS-citrate with DMSO alone for the positive control) and added to aliquot in a v/v ratio of 3:1 using Sysmex, XT-1800i, Japan at The Hematology Laboratory, Hematology Department, Medical Research Institute, Alexandria University.

Characterization of copper oxide nanoparticles

The synthesized CuO NPs were characterized using Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM), X-ray Diffraction (XRD), Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), and Zeta potential (ζ). The results obtained are further explained.

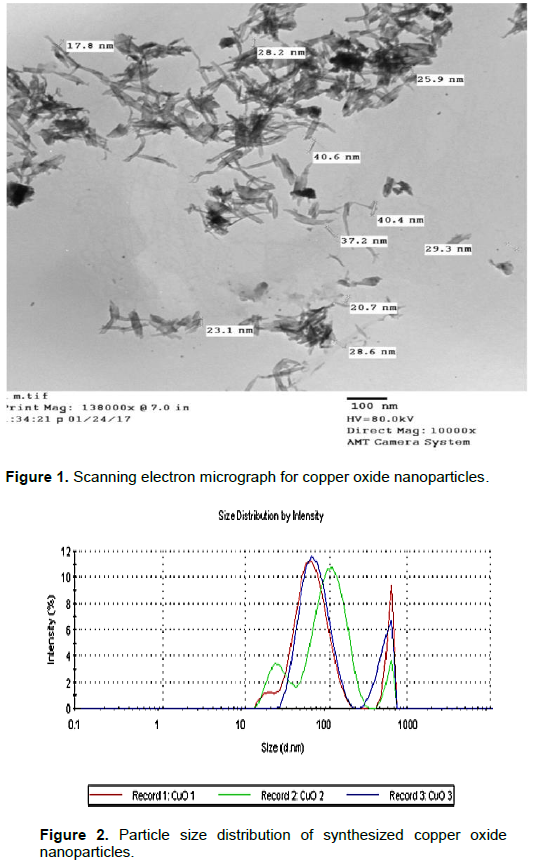

Scanning Electron Micrograph of CuO nanoparticles

The shape and the size of CuO nanoparticles were determined by SEM image. The SEM micrograph of CuO nanoparticles appeared as wire-like images with an average size of 27 nm and are shown in Figure 1.

Particle size analysis and zeta potential measurements

Particle size: The average hydrodynamic diameter and poly-dispersity index (PDI) of CuO nanoparticles were determined by Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) using Malvern zeta sizer. The hydrodynamic diameter of chemically synthesized CuO nanoparticles was 82.24 nm, and the PDI was 0.426 as shown in Figure 2.

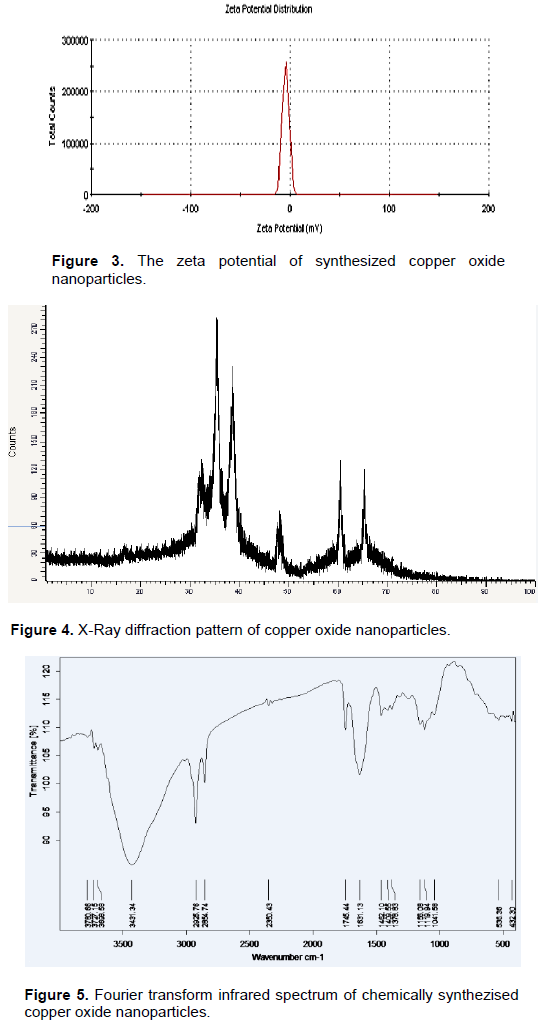

Zeta potential measurement: The potential of the synthesized CuO nanoparticles was performed using Zeta Sizer (Malvern, UK). The zeta potential of synthesized CuO nanoparticles was -4.69 mV as shown in Figure 3.

X-ray diffractometer: The crystalline nature of the synthesized CuO nanoparticles was identified from their corresponding powder XRD patterns as shown in Figure 4. The diffraction peaks were well matched with the monoclinic phase of CuO (standard JCPDS File No: 048-1548). Diffraction peaks with 2Ó¨ values of 33.6°, 35.45°, 38.73°, 48.92°, 61.99°, and 66.49°, respectively were indexed to (110), (002), (111), (020), (022) and (113) planes.

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy: The Fourier Transform Infrared spectra of CuO nanoparticles as shown in Figure 5 depicts that broad absorption peak at 3431 cm-1 was caused by adsorbed water molecules. Since the nanocrystalline materials possess a high surface to volume ratio, they can absorb moisture. The peaks at 1631 cm-1 depict the Cu-O symmetrical stretching. The high-frequency mode at 536.36 and 432.30 cm-1 can be assigned to the Cu-O stretching vibration. Moreover, no other IR active mode was observed in the range of 605 to 660 cm-1, which totally rules out the existence of another phase, that is, Cu2O. Thus, the pure phase CuO nanoparticles with monoclinic structure is also confirmed from the FTIR analysis.

Copper ions are redox-active, which means that the high intracellular concentration gained after the dissolution of CuO nanoparticles within the cell likely results in massive oxidative stress. Various signs of oxidative stress and genotoxicity have been observed upon cellular exposure to CuO nanoparticles.

Effect and evaluation of copper oxide nanoparticle toxicity on human RBCs

From data obtained from the research study, there is no notable effect of CuO nanoparticles on RBC counts after ½ h incubation as compared with controls. After 3 h incubation, there is no significant reduction in the RBC count as compared with negative control and positive control samples. On the other hand, there is a significant reduction in the RBC count after 24 h incubation because of hemolysis as shown in Figure 6 and Table 1.

Scanning electron micrograph of RBCs examination

The examination of the RBCs using SEM were done by fixation in 01% glutaraldehyde and incubated for another hour at room temperature and centrifuged at 1550 g and 37°C for 10 min (Figure 7). The supernatant was exchanged with PBS-citrate, and the samples were vortexed, centrifuged at 1550 g and 37°C for 10 min and fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde for an hour.

Osmotic fragility of RBCs

Figures 8 and 9 show the variation of hemolysis percentage as a function of NaCl concentration percent. The figures indicate a shift in the Median Corpuscular Fragility (MCF); that for the control group at 35, group (100 ppm) at 40, group (200 ppm) at 45, and group (400 ppm) at 50 indicating a decrease in the RBCs resistivity to hemolysis. These results appear more evident in the differentiation curves as shown in Figure 9 for blood samples. The formed peaks indicate the increase in the hemolysis of RBCs. From the differential curves, we determined the maximum hemolysis rate (Cmax), the half-maximum width of the peak (Whmax), which represents the elastic range of the cell membrane and H50, which represent the concentration percentage of NaCl that leads to 50% hemolysis.

The effect of copper oxide nanoparticles on active platelets

To study the effect of CuO nanoparticles on the number of active platelets, different concentrations of CuO nanoparticles were incubated with platelets for 24 h. Table 2 and Figure 10 show the change in the number of active platelets after 24 h incubation.

Copper ions are redox-active, which means that significant oxidative stress is possibly due to the high intracellular concentration obtained after the dissolution of CuO nanoparticles within the cell. At cellular exposure to CuO nanoparticles, various signs of oxidative stress and genotoxicity were observed (Ahamed et al., 2006; Hanagata et al., 2015). The CuO nanoparticles were successfully synthesized using a chemical process. The nanoparticles were characterized in detail using Zeta sizer, Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM), X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) analysis, and Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR). The TEM analysis of CuO nanoparticles revealed their irregular wire-like nature with an average size of 27 nm. Zeta potential (ζ) measured by Zeta sizer revealed that the particles carry a small negative charge of -4.69 mV. The XRD pattern showed that all the diffractions peaks were well matched with the monoclinic phase of CuO nanoparticles with 2Ó¨ values of 33.6°, 35.45°, 38.73°, 48.92°, 61.99°, and 66.49°, respectively were indexed to (110), (002), (111), (020), (022) and (113) planes. XRD and TEM analysis confirmed the high crystallinity and uniform non-agglomeration of synthesized CuO nanoparticles.

FTIR analysis was performed in order to understand the chemical and structural character of the synthesized nanomaterials and the influence of the chemicals used in the synthesis. Also, infrared studies were carried out in order to ascertain the purity and nature of the metal nanoparticles. The FTIR spectra of CuO nanoparticles showed the presence of peaks at 3431 cm-1, which indicates that the nanoparticles are surrounded by water molecules which contained the hydroxyl group. The peaks at 1631 may be for the Cu-O symmetrical stretching. The high-frequency mode at 536.36 and 432.30 cm-1 can be assigned to the Cu-O stretching vibration. Moreover, no other infra-red active mode was observed in the range of 605 to 660 cm-1, which totally rules out the existence of another phase, that is, Cu2O. Thus, the pure phase CuO with monoclinic structure is confirmed from the FTIR analysis. The data obtained for characterizing chemically synthesized Copper Oxide Nanoparticles was verified by those obtained by El-Trass et al. (2012). In agreement with our results, several other research groups have also documented dose-dependent cytotoxicity of nanoparticles exposed cells (Fernández-Alberti and Fink, 2000). CuO nanoparticles showed toxicity in mammalian cells, leading to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), oxidant injury, excitation of inflammation, and cell death (Oyawale et al., 1997). The nanoparticles are capable of penetrating, translocating within, and destroying living cells. This ability results primarily from their small size, which allows them to penetrate or attach to the cell membrane causing deformation and subsequent cell death.

The outcomes of the osmotic fragility curves provide information on the changes in the elasticity and ionic permeability of the red blood cells membrane, which plays a significant role in the RBCs metabolic activities. Since the diameters of the RBCs are in the range of 12 to 16 μm, each RBCs has to flow through narrow blood capillaries of smaller diameters (~8 μm) to reach the target cells in the body to carry-out the metabolic reaction, the RBCs have to be folded several times to decrease their diameters in order to pass through blood capillaries under high pressures according to Bernoulli's equations. The elasticity of the RBCs membrane will play a significant role in the folding process, any decrease in its elasticity will lead to the loss of the folding mechanisms that will permit the RBCs to carry-out its function, which will cause anemic diseases. The change in cell membrane elasticity can be distinguished from the Whmax values in the differential curves of osmotic fragility, that is, the decrease in the Whmax clearly shows the decrease in the elastic range of the RBCs membrane.

Furthermore, platelet counts decrease as the incubation period with CuO nanoparticles increased, and its dosage increased. The significant decrease in the count of platelet indicated competent and supportive immune responses which could have negative effect of Cu-NPs or CuO to promote blood thickening, which in return caused platelet damage. The same results obtained for the whole blood PLT count showed a substantial decrease in the PLT after 24 h of incubation with CuO nanoparticles and decreased the count as the concentration of CuO nanoparticles increased (Noureen, 2018).

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Ahamed M, Siddiqui MA, Akhtar MJ, Ahmad I, Pant AB, Alhadlaq HA (2006). Genotoxic potential of copper oxide nanoparticles in human lung epithelial cells. Journal of Biochemical Biophysical Research Communications 396(2):578-583.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Ayyub P, Palkar VR, Chattopadhyay S, Multani M (1995). Effect of crystal size reduction on lattice symmetry and cooperative properties. Journal of Physical Review B 51(9): 6135-6138.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

El-Trass A, ElShamy H, El-Mehasseb I, El-Kemary M (2012). CuO nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization, optical properties and interaction with amino acids. Journal of Applied Surface Science 258(7):2997-3001.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Fernández-Alberti A, Fink NE (2000). Red blood cell osmotic fragility confidence intervals: a definition by application of a mathematical model. Journal of Clinical Chemical Laboratory Medicine 38(5):433-436.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gleiter H (2000). Nanostructured materials basics concepts and microstructure. Journal of Acta Materialia 48:1-29.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Griffitt RJ, Weil R, Hyndman KA, Denslow ND, Powers K, Taylor D, et al (2007). Exposure to Copper Nanoparticles Causes Gill Injury and Acute Lethality in Zebrafish (Danio rerio). Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 41(23):8178-8186.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gurr JR, Wang AS, Chen CH, Jan KY (2005). Ultrafine titanium dioxide particles in the absence of photoactivation can induce oxidative damage to human bronchial epithelial cells. Journal of Toxicology 213(1-2):66-73.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hanagata N, Zhuang F, Connolly S, Li J, Ogawa N, Xu M (2015). Molecular responses of human lung epithelial cells to the toxicity of copper oxide nanoparticles inferred from whole genome expression analysis. Journal of American Chemical Society Nano 5(12):9326-9338.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Heinlaan M, Ivask A, Blinova I, Dubourguier HC, Kahru A (2008). Toxicity of nanosized and bulk ZnO, CuO and TiO2 to bacteria Vibrio fischeri and crustaceans Daphnia magna and Thamnocephalus platyurus. Journal of Chemosphere 71(7):1308-1316.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hobbie RK, Roth BJ (2006). Curves differentiation. In: intermediate physics for medicine and biology. 4th ed New York NY: Springer.

|

|

|

|

|

Iancu C, Ilie IR, Georgescu CE, Ilie R, Biris AR, Mocan T, Mocan LC, Zaharie F, Todea-Iancu D, Susman S, Ciuca DR, Biris AS (2009). Applications of nanomaterials in cell stem therapies and the onset of nanomedicine. Journal of Particulate Science and Technology 27:562-574.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ilie I, Ilie R, Mocan T, Iancu C, Mocan L (2013). Nicotinamide-functionalized multiwalled carbon nanotubes increase insulin production in pancreatic beta cells via MIF pathway. Interntional Journal of Nanomedicine 8:3345-3353.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Jadhav S, Gaikwad S, Nimse M, Rajbhoj A (2011). Copper Oxide Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization and Their Antibacterial Activity. Journal of Clust Science 22:121-129.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Jahanbakhshi A, Hedayati A, Pirbeigi A (2015). Determination of acute toxicity and the effects of sub-acute concentrations of CuO nanoparticles on blood parameters in Rutilus rutilus. Journal of Nanomedicine 2(3):195-202.

|

|

|

|

|

Martin CR (1994). Nanomaterials: A Membrane-Based Synthetic Approach. Journal of Science 266(5193):1961-1966.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mocan T, Clichici S, Biris AR, Simon S, Catoi C, Tabaran F, Filip A, Daicoviciu D, Decea N, Moldovan R, Mocan L, Muresan A (2011). Dynamic effects over plasma redox ballance following subcutaneous injection of single walled carbon nanotubes functionalized with single strand DNA. Digest Journal of Nanomaterials and Biostructures 6(3):1207-1214.

|

|

|

|

|

Noureen A, Jabeen F, Tabish TA, Yaqub S, Ali M, Chaudhry AS (2018). Assessment of copper nanoparticles (Cu-NPs) and copper (II) oxide (CuO) induced hemato-and hepatotoxicity in Cyprinus carpio. Journal of Nanotechnology 29(14):144003.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Oyawale JO, Okewumi TO, Olayemi FO (1997). Haematological Changes in West African Dwarf Goats Following Haemorrhage. Journal of Veterinary Medicine A 44: 619-624.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Pattanayak M, Nayak PL (2013). Ecofriendly green synthesis of iron nanoparticles from various plants and spices extract. The International Journal of Plant, Animal and Environmental Sciences 3(1):68-78.

|

|

|

|

|

Rao CN, Müller A, Cheetham Ak (eds) (2004). The Chemistry of Nanomaterials: Synthesis, Properties and Applications. Weinheim: WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA pp. 1-11.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ren G, Hu D, Cheng EW, Vargas-Reus MA, Reip P, Allaker RP (2009). Characterisation of copper oxide nanoparticles for antimicrobial applications. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 33(6):587-590.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Rodríguez JA, FernaÌndez-GarciÌa (eds) (2007). Synthesis, Properties, and Applications of Oxide Nanomaterials. Hoboken N.J: Wiley-Interscience.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Suleiman M, Mousa M, Hussein A (2015). Wastewater disinfection by synthesized copper oxide nanoparticles stabilized with surfactant. (Doctoral dissertation).

|

|

|

|

|

Sun CQ (2003) Oxidation electronics: bond-band-barrier correlation and its applications. Journal of Progress in Materials Science 48:521-685.

Crossref

|

|