ABSTRACT

This study was conducted to assess key livelihood strategies and to examine major socio-economic constraints that hinder households from engage in diversified activities, in two Peasant Associations of Boricha Woreda, Southern Ethiopia. From the two Peasant Associations, 110 households were selected through simple random sampling technique. Both primary and secondary data were collected to come up with dependable conclusion. Primary data were collected by conducting survey and participatory rural appraisal tools. The primary data was gathered through structured household questionnaire and further supplemented by key informant interview and focus group discussions. Quantitative data which was collected from primary sources were analyzed using SPSS 20.0 version and reported through descriptive statistics like mean, standard deviation, percentage and frequency distribution. In the study area, rural households engaged in portfolio of livelihood activities though farming activity taken as the major share (87%) followed by trade (68%) and other off-farm activities. However, the participation in diversified livelihoods is constrained by low awareness level of farmers to adopt modern technologies, lack of credit, weak extension services, lack of skill, wrong attitude of the local community, and household average income. Based on the findings, strengthening access of start-up capital to initiate small businesses through cooperatives and credit institutions, providing vocational training to increase households’ skill to use locally available resources, improving access of rural infrastructure, strengthen the implementation of functional adult literacy program and increasing awareness level of the community through training were suggested as recommendations.

Key words: Assets, livelihood diversification, migration, non-farm.

Livelihood diversification strategies have become important income generating activities for rural households in major developing countries. Although agriculture has remained the dominant livelihood strategy for more than 85% of rural labor force in Sub-Saharan countries (World Bank, 2007), its productivity is one of the lowest and even showing a decreasing trend causing a decline in per capita cereal consumption Nandeeswara Rao and Bealu (2015). Because of rapidly growing rural populations and declining farm sizes, the rural employment problem needed to be addressed there as well (World Bank, 2008). This clearly shows that farming alone hardly provide a sufficient means of survival in rural Ethiopia due to increasing human population, climatic factors, and lack of money to purchase agricultural inputs . To this end, the important role of non-farm livelihood strategies to ensure livelihood security has been noted by many scholars (Workneh, 2006; Ansoms and McKay, 2010; Soltani et al., 2012, Assan and Beyene, 2013). Additionally, the important role of non-farm and/off-farming livelihood strategies in Ethiopia has been highly magnified due to the occurrence of recurrent drought that affect agriculture based livelihoods and increasing number of landless youths, who are barely absorbed in the rural labor market. There fore rural livelihoods diversification can be accepted as desirable and a key focus of poverty reduction strategies in developing countries such as Ethiopia (Ellis, 2000; Carswell, 2002; Bezu et al., 2012). Again, the increasing importance of rural livelihood diversification in Ethiopia has drawn the attention of various scholars in recent years to target on positive impact of diversification as a means to expand peoples’ choices, increase households’ income, enhance their capabilities and assets (Assan and Beyene, 2013,) and reduce risks associated with rain-fed agriculture (Ayele, 2008). The proponents of diversification argue that it will help the rural economy to grow fast by increase investment on farm activities (Holden et al., 2004).

However, livelihood diversification smoothers risks associated with traditional agriculture, all households, and social groups do not have equal opportunities for engagement. Different factors such as experience, family size, educational attainment, level and physical assets of households can affect participation in diversification activities (Khatun and Roy, 2012). Lemi (2005) also reported that intensity of diversification is affected by the size of land holdings, value of livestock owned and level of income from crop production. He also pointed out that demographic factors, such as the age and gender of the household head, dependency ratio and number of female household members are determinants of participation. Supporting this, Degefa (2005), argued that the meaning and reason for livelihoods diversification is different for rich and poor households and for the households headed by women and men. This indicates that livelihood strategies and diversification are dynamic and sensitive to geographic, socio-economic and institutional settings which need area specific investigation (Ellis, 2000). In addition there were few studies on the challenges of rural livelihood diversification in the Woreda. This study therefore, attempted to fill this gap by examining the potential livelihood diversification activities in the Woreda; and the major challenges hindering diversification activities currently underway.

General objective of the study

The general objective of the study was to examine alternative rural livelihood strategies and socio-economic challenges of livelihood diversification in Boricha Woreda. More specifically, the study attempted to:

i) Assess the major livelihood strategies/options/ practiced by the rural community in Boricha.

ii) Sort out the major constraints faced by rural house holds with respect to livelihood diversification.

Description of the study area

The study area, Boricha Woreda, is found in Sidama zone, Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Region (SNNPR), which is located at 305 km south of Addis Ababa and 35 km south-east of Hawassa; the capital of the region and Sidama zone. The total area of the woreda is about 588.1 km2 with the altitude between 1001-2000 masl. The woreda receives mean annual rain fall that ranges from 801 to 1000 mm. The mean annual temperature of the woreda is 17.6-22.5°C. The woreda has a total population of 280,419, out of which 267,872 are rural and 12,548 is urban population (SZFEDD, 2015). It is one of the moisture stress and sometimes food insecure areas of the zone. Farming system of the study area generally depends on rain fed agriculture and mixed farming system which involves both crop production and animal husbandry. Maize, haricot bean and teff are the major crops while cattle and shaot are dominat livestock type. High population density, fragmentation and declining land holding size, deforestation, declining soil fertility, small and unreliable rain fall and resulting food insecurity are major defining characteristics of the place under study (Bechaye, 2011; SZFEDD, 2015). According to the report of Agriculture and natural resource development office (2014), the increasing population reduced the average size of land owned by households to less than one hectare, and this forced 7,750 households of the woreda to seek food aid through Productive Safety Net Program. All these consequences of population pressure have jeopardized the sustainability of the traditional mixed farming systems and have adverse implications for household food security if it is not diversified with other activities (Abebe, 2013; Nigatu et al., 2013).

Research design

The study employed mixed study design with cross-sectional survey strategy which is important to assess the prevalence of practices, attitudes, knowledge and skill related with livelihood strategies of the study population at specific time (Ellis, 1999, 2000). During the study, both qualitative and quantitative approaches have been employed to collect the in-depth data. Qualitative methods are useful for improving the depth of our understanding of the local circumstance that households operate in, while quantitative tool help us to determine the breadth to which observed behavioral practice, resources, or problems are distributed within a population (Ellis, 2000).

Sample size and sampling procedures

Three stage sampling design has been used to come up with more representative sampling unit and size. In first stage, Boricha Woreda was selected purposively because it is under the catchments of university’s Technology Village and its accessibility. In the second stage, two peasant Associations (Dila Arfe and Shelo Elancho) were randomly selected considering the agro-ecological homogeneity of the woreda. Additionally, considering financial ant time constraint of the authors (Ellis, 1999), a total of 110 households, which means 55 households from each peasant association, were selected through simple random sampling technique. Hence, the original list of household heads from kebele office for the year 2015 was the sampling frame.

Types and sources of data

This study was conducted by collecting necessary information from the primary and secondary sources. Sampled households, key informants and focus group discussion participants were the main sources for primary data while published and unpublished documents such as books, journals, office records and reports have been the key sources for secondary data.

Methods and tools of data collection

Household survey

The structured household survey has been mainly used to collect quantitative data from the selected sample households to generate information on the general socio-economic conditions. Most of the questions were close-ended and the few are open-ended for the sake of consistency and simplicity to analysis. The survey was handled by Development Agents (D.As) of the respective Kebeles’ after taking one day training and orientation to make the questions clear under the close supervision of the researchers. To get additional in-depth data for further triangulation, four groups of focus group discussions were conducted with men and women groups, landless youths. Additionally, development agents, community leaders, relevant heads of woreda offices were interviewed to depict their efforts and degree of coordination in facilitating livelihood diversification. Further more; secondary data has been collected from relevant books, journals, articles, reports and publications of various levels of government bodies.

Data analysis and interpretation

To address the various objectives of the study, both quantitative and qualitative data analysis techniques have been considered. Data were entered in to computer after coding the variables. Then descriptive statistics such as mean, frequencies and percentages were computed by using the statistical packages for social scientists (SPSS/ version 20.0) software program. Then after, results were presented in tables, figures, and interpreted accordingly. Similarly, qualitative data were analyzed by describing (narrating) and interpreting the situation in detail and contextually.

Demographic features of sample households

Age – Sex composition of sample households

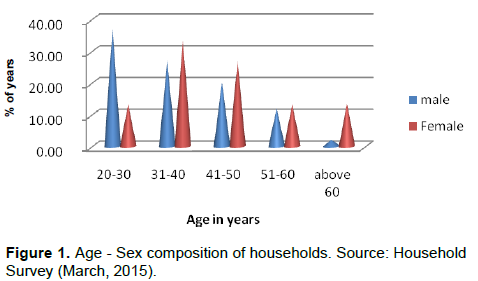

Regarding the age of the respondents, more than 60% were fall under the age ranges from 20 to 40 years followed by 12.7% under 51-60 and 3.6% above 60 years. When it is disaggregated by gender, 73.3% of female headed households fall under ranges between 20 -50 years and the remaining 26.7% is above 50 years (Figure 1). According to the survey, most of the respondents (76.3%) were grouped under productive age while only 3.6% (N=4) fall above 6o years. This implies that most of the respondents can pursue different livelihood activities either in their locality or through cyclical migration.

As indicated in the figure, majority of the respondents (86.4%) are male and the remaining 13.6% (N=15) are female headed households. The survey found that the numbers of female-headed households are very small. This implies that in the community, sometimes, male children are considered as the head of the household when they become divorced or widowed. In female-headed households, all the decisions such as allocating land, labor and other resources that determine the economic status of the given family are held by women. These responsibilities doubled the burden of women in both agricultural as well as non-agricultural activities. This suggests that headship of the households necessarily influences the livelihood strategies of women in Woreda.

Family size of respondents

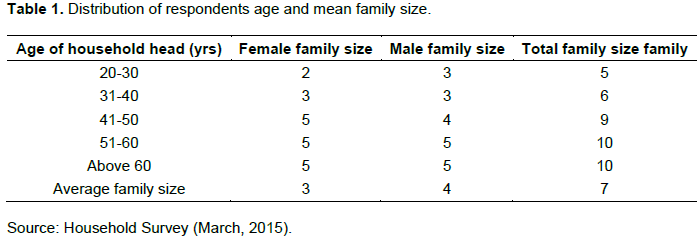

The mean family size for the sample households was found to be 7 members. This is in line with national average fertility rate of 6 children per woman in the rural parts of Ethiopia in general (Susuman et al., 2014) and Sidama in particular (SFEDD, 2015). The large amount of family size could be an input to assign adequate labor to be engaged in different livelihood activities. This is because households with large family size may have more chance to pursue diversified livelihood activities in on-farm or off-farm activities to pool income from different sources.

According to key informants and focus group discussion participants, in the far past years, having many children was considered as prestige and the community members were encouraged even to have more than one wife to have many children. The community also gives more preferences for male children than females. Though the situation is being improved, there are some occurrences of polygamy and male preferences in rural areas of Boricha Woreda. It was found that large family size has negative impact on farm size, but creates favourable condition for non-farm livelihood diversification as to assign different members in different livelihood activities. Similarly, Tegegn (2001) found that education and family size influences household’s diversification away from farming in Southern Ethiopia (Table 1).

There was competition for the farm labor between farm activities and non-farm commitments. However, households with large family size could easily solve this problem by sharing the available labor among different livelihood strategies. Hence, the larger family size, the more non-farm activities the rural farm households likely to have and increased total income. The finding is consistent with that of Tegegn (2001).

Educational background of sample households

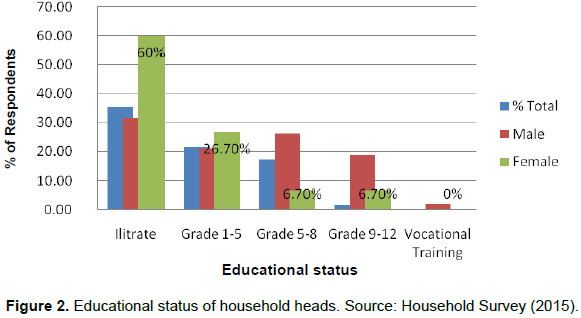

About 35.5% of the respondents could not read and write, while 21.8% were enrolled for grades 1-4, whereas, 23.6% completed grades 5-8, and the remaining 17.3% completed 9-12 grades. When the data is disaggregated in to gender wise, 60% of female headed households are illiterate, 26.7% are grouped under 1-4, followed by 6.7%, 8-12 grades respectively (Figure 2). The educational status of sample households was found to be encouraging when compared to other rural parts of the country. According to the Central Statistics Agency (CSA, 2014), 49% of females and 37% of males had never enrolled for school nationally. Similarly, Sidama zone education department reported (2014) that girls’ enrolment and achievement was low especially for second cycle education due to early marriage, poverty, etc. The same data indicates, only 31.6% (N=30) males are illiterate whereas 60% (N=9) females are illiterate. From this, one can easily concludes that as grade level increases, the number of educated female household heads decreases. The survey revealed that, male and female did not have equal access to education and training in the Woreda due to various socio-cultural barriers.

Major livelihood activities or strategies in the study area

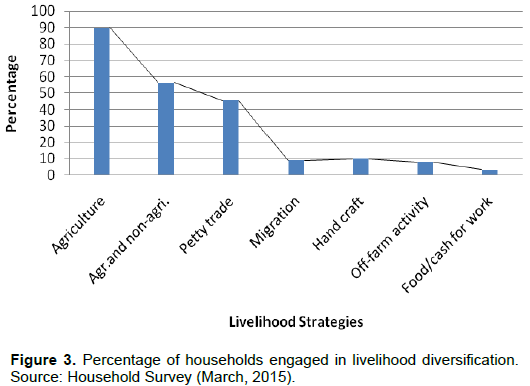

Sustainable rural development requires multi-disciplinary approaches to poverty reduction. The agricultural focus is essential, but not sufficient for sustainable rural development due to constraints such as scarcity and degradation of agricultural land, weak extension services, lack of skill and training, low input supply and high price, lack of road network and unreliable rain fall (Figure 3) (World Bank, 2007). In addition to agricultural activities, the rural households should practice non-farm activities to improve their incomes (World Bank, 2008). Non-farm activities are very heterogeneous which include hand crafts, self-employed enterprises as well as wage employment in public or private organizations. In the case of Boricha Woreda, the most important non-farm activities are trade (live stocks as well as livestock products and crops followed by trading manufactured commodities), wage/salary in Governmental organizations as well as NGOs, Food stuff production and selling.

Agriculture

Agriculture is major livelihood strategy in the area. But about 56% of sample households are engaged in various non-farm activities as supplementary to agricultural activities. However, out of all households participated in non-farm activities, 45.5% were engaged in marketing different types of agricultural products and consumer goods. This result coincides with the findings of Tegegn (2001) from Damot-Gale and Kachabira Woredas of Southern Ethiopia. According to him, trade was the most important non-farm livelihood activity in that area. The other portion of households engaged in different hand crafts, renting (hiring) oxen, pack animals and land.

Off-farm activities

Working as a wage labor was also common way of diversifying livelihood activities to improve living standard in the study area. Particularly, this mechanism was used by the poor households with inadequate asset base or social networks to support them in times of food and income shortage. In times, when no agricultural activities exist /slack season/, working as a daily laborer serve as additional job opportunity. However, in the study area, only 9(8.2%) male headed households were engaged in wage labor especially in agricultural labor. According to FGDs and key informants interview participants, the society has negative attitude towards wage labor and wage laborers. So, the man who interested to engage in wage labor prefer to go to other cash crop growing areas such as Hawassa, rather than engaged in the study area due to fear of ridicule of the society. Therefore, in this area, lack of labor market is the most important constraint for off-farm livelihood diversification. As discussed earlier, the people do not need to be engaged in such type of employment due to fear of negative attitude of the society. In addition to agricultural wage labor, 3.6% of respondents engaged in FFW/CFW program, which is sponsored by Safety Net program. The beneficiaries of this program are mostly poor households who are selected by the community according to its own criterion. The unhealthy and elderly peoples benefited from the program freely without any contribution of labor.

Trade

Trade is the most important livelihood activity in the Woreda following the agricultural activities. As the survey revealed, out of all sample households, more than 50% of the sample household, were engaged in one or two non-agricultural activities to supplement the dominant activity, agriculture. Out of all non-farm economic activities, trade took the lion’s share. This is because the majority of sample households are grouped under productive age as to actively participate in trading. The implication is that Shelo Elancho Kebele is located in proximity to the Woreda capital as to facilitate the engagement of significant amount of sample households in trading. The survey revealed that 45.5% of sample households out of all households who engage in non-farm activities were participants in various trading of agricultural products. In a similar manner, Carswell (2002) and Tegegn (2001) found that in Wolayita area, trade is a common diversification activity practiced by different income groups on different scales. The marketing of livestock and livestock products is concerned; Boricha Woreda has good potential for animal population both Cattle and Shoats (Goat). In addition, Yirba, Balela and Darara markets have been serving as a centre of exchange, for merchants who brought livestock to Sidama and Wolayita zones. However, the activity was very tier-some due to lack of transportation and lack of improved marketing system. They use pack animals (especially donkey-pulled carts) to transport small quantities from one market to the other. Selling of home-made food and drinks is the other source of income for a number of female-headed households in the area.

Hand crafts

These categories of economic activities are the least developed and not recognized by the community understudy. As Figure 2, demonstrates that only 11 households (10%) were engaged in hand craft activities. According to the key informants and FGDs participants, major constraints of the sector are lack of demand by the community, lack of skill training to produce quality products and lack of start-up capital. On the other hand, the attitude of the society towards these professionals is not as such supportive. They consider them as minorities and caste while using all the products produced by the professionals. Thus, these constraints should be solved in order to secure livelihood of these people which in turn expands cottage industries in the rural area.

In addition to the finding of the household survey FGDs reports revealed that; lack of transportation, lack of time, lack of storage facilities and costly inputs were serious problems for non-farm diversification in the kebeles. This situation shade light that the activities need promotion to raise market demand as well as to build the capacity of the practitioners through provision of credit, inputs and cooperatives, to learn each other/pool knowledge and skills.

Migration

Migration has been identified as one of the coping mechanisms and diversification way by different scholars (Ellis, 2000). Regarding the situation of Boricha Woreda, only 9.1% (N=10) was involved in migration. The place of destination is concerned; and mostly youngsters migrate for coffee harvesting to Dale and Shebedino districts during off-season. In addition, some groups of youngsters go to Hawassa and Leku during Kiremt season. As the key informants report and the researchers’ observation as well, the community under study was not as such mobile rather it was highly tied with kinship and family bonds. Remittance was found to be insignificant for the sample households in the study area. Out of all sample households only 7 household heads were reported as they are beneficiaries of remittance. This implies that migration and remittance covers the lowest portion of the income portfolio in the study area.

Constraints of livelihoods diversification in Boricha

Although rural non-farm sectors provide various significances for rural households, the opportunity is not equal for all rural households. Concerning the entry barriers to non-farm activities in Boricha Woreda, the

survey reported the various evidences. In this respect, lack of skill and experience (68%), lack of initial capital (62%), lack of market and raw materials (54%), negative attitude of the society (52%) and poor infrastructure (47%) respectively were reported as major challenges for non-farm diversification in the study area (Figure 4). In line with this, Bedemo et al. (2013) also reported access to credit and farm size as major challenges off farm livelihood diversification decision in western Ethiopia.

Lack of transportation as challenge for livelihood diversification

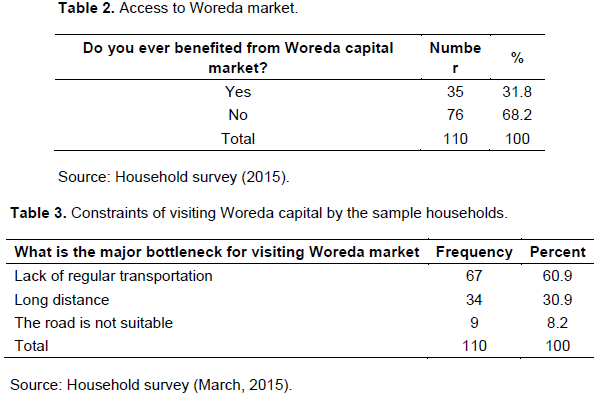

The economic importance of roads and access to market play a major role in motivating farmers to improve their productivity and to pursue different livelihood strategies. Majority of the Kebeles in the Woreda are not connected with the Woreda center as well as with the zonal capital. Out of the sample households, only 31.8%( N=35) are beneficiaries of the market from Woreda capital whereas, 68.2% (N=76) do not get benefits from the market of the Woreda center because of long distance (more than 2 km) and lack of adequate means of transportation (Table 2).Furthermore, the respondents also asked the major constraints that hinder to get benefits the marketing service of the Woreda capital. Out of total sample households, 60.9% (N=67) replied that lack of regular transportation and 30.9% (N=34) responded long distance from the town by taking two killometers as a relative reference. However, the remaining 8.2% (N=9) reported as the road is not suitable for the journey to Woreda capital market. This implies that, lack of transportation is the determining factor for livelihood diversification in the Woreda (Table 3).

In a net-shell, lack of physical capital has been played negative role in the livelihood of the society in general and pursuing diverse activities in particular. So, expansion of rural infrastructure such as road, rural electrification and wireless telecommunication services would be strengthened to achieve the goal of household livelihood security as well as rural development.

The other and more promising prospect for diver-sification of livelihood for the population of the Woreda is the upgrading of the Morocho-Dimitu road in to Asphalt level. This is because about 30% of the kebeles are crossed by this road and a project is on the way to start their actual work.

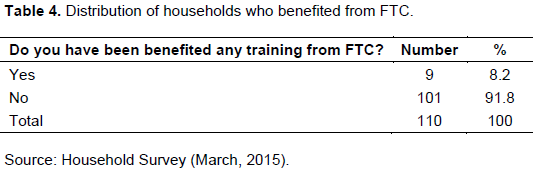

Inadequate skill / training

The importance of literate, skilled and healthy labor force with positive attitude and behavior in making farm and non-farm activities is now widely recognized. Although the survey revealed 35.5% of the sample household heads are illiterate, lack of vocational training found to be constraint of diversification. According to the BWARDO, lack of vocational skill training is a serious obstacle to the expansion of income source diversification in the Woreda. The key informants’ interview further confirmed that illiterate farmers are mostly reluctant for the application of new technologies than the literate ones. This result is consistent with the finding of Tegegn (2001) which confirmed that non farm skill training significantly influences income diversification strategies. Households with low educational attainment give more attention for traditional beliefs and has wrong attitude towards handcrafts such as metalwork, wood work, weaving, pottery and so on. With regard to vocational skills training facilities, out of the sample household heads, only two respondents have vocational training. Although the government’s objective was to transform rural economy by disseminating knowledge through training, as to increase productivity, and to make them competitive at market, the survey revealed that only 9(8.2%) household heads were benefited from the training. Some key informants also reported that there are serious coordination problems from all levels of government to make the objectives of FTCs operational (Table 4).

From this, one can understand that lack of knowledge and vocational skill hinders the rural farm family from diversifying their income sources. The physical availability of Farmers’ Training Canters (FTCs) does not provide any change in the Woreda understudy. Most of the FTCs are poorly designed, poorly constructed; and stand alone without door, window and allocated with in adequate plot of land for experimentation. This implies that any effort of rural development in general and capacity building should be coordinated and demand-driven.

In adequate access to financial capital

Most of the existing formal financial intermediaries in the study area are limited to urban centres. The bulk of rural people rely on the informal financial sectors (that is, iqqub, Iddir, private money lenders, and friends and relatives) for their credit requirements. The survey indicated that more than 50% sample households borrow money from informal institutions such as Iddir, relatives, and friends. The others have been benefited from traditional reciprocal money saving mechanisms called Equb. Only 22(20%) are borrowed money from formal financial institutions. The mean average money borrowed by the sample households’ is 1273 Ethiopian Birr. This shows that majority of rural households in the study Woreda are not beneficiaries of formal microfinance institutions which are believed to solve the liquidity problems of rural population by many scholars. This indicates the urgency of intervention which solves problems as to improve the access of financial capital and saving culture of the community under study.

Here again, the survey result is supported by the findings of the in-depth interviews. In case of identifying the major requirements to expand non-farm livelihood activities, according to the interviewees, the following results were reported. The key informants emphasized on the access to skill training including business management, access to initial capital including saving, access to raw materials (especially for hand craft sector), access to infrastructure (road, electricity, tele-communication which is highly capitalized from Dila Arfe). Almost more than half of the interviewees reported that all the above assets should be fulfilled to expand non-farm activities. The data revealed that more respondents had no access to credit and indicated different reason for not approaching formal lending institutions for loan. Approximately, 37% of the respondents reported that they do not know where they go to get credit, 29% had no collateral, 22% feared loans, and 3% said do not have skill to engaged in trade. In the same manner, Khatun and Roy (2012) found that poor asset base, lack of credit facilities, lack of awareness and training facility, lack of rural infrastructure, lack of opportunity in non-farm sector are major challenges for non-farm diversification. This implies that both accessibility and affordability problems of financial capital would be solved through supply side as well as demand side interventions to expand households’ livelihood choices.

1) In the study area rural, farming activity took its major share although some of the households engaged in portfolio of livelihood activities such as trade, hand crafts, animal fattening, wage employment in cash for work/safety net programs/.

2) The engagement in to other activities is constrained by various socio-economic and institutional factors such as lack of job-opportunity, negative attitude of the community, lack of initial capital, lack of skill training, lack of market, lack of infrastructure (telecommunication, road, and electric power), lack of raw materials, low institutional capacity and lack of coordination of the BWARDO.

3) The finding indicates that the major source of finance for non-farm investment comes from own saving and loans from relatives, friends and money-lenders. Lack of flexible and affordable credit services and high interest rate are also the major problems of diversification in the woreda.

4) In general, lack of skill and training, lack of credit, inadequate infrastructure, low institutional capacity and lack of coordination among implementing bodies, wrong perception of the community towards hand crafts and limited entrepreneurial skill are the major constraints of rural non-farm livelihood diversification in the study area.

1) Successful diversification of rural livelihoods requires investment in human capital as to facilitate adoption of technologies that accompany investment and technological change in rural areas. Therefore, the issue of developing skill of rural community through Farmers’ Training Centers by using Development Agents should be strengthened to expand the option of rural household’s livelihoods.

2) Regional as well as local government bodies should play critical role in connecting rural communities with all weather roads in order to facilitate rural-urban linkages and its economic implications by constructing and maintaining feeder roads. The current trend of rural electrification, expansion of telecommunication services in rural kebeles as well as the expansion of road networks by the Federal Government through Universal Access Program/ URAP/ should be strengthened.

3) Any developmental intervention should consider the gendered differential access to key livelihood assets. So, first of all these socio-cultural barriers to access and ownership of livelihood assets for women should be considered and solved in order to expand the economic capacity of women through diversification. Therefore, gender considerations are needed to be emphasized in promoting rural employment opportunities.

4) Access to credit enables rural households to expand their livelihood options. Therefore, new strategy should be devised to strengthen and expand rural financial institutions that ensure access to credit for rural households as to engage in diversified livelihood activities. Furthermore, measures are needed to be taken to build the financial and managerial capacities of informal financial institutions, group-lending to raise credit, saving and establish insurance schemes. This can be done specially through facilitating condition for interested parties or establishment of credit providing institutions in the study area. In general, policy makers should consider diversified livelihood strategies that encourage various income generating activities, increasing access to credit and creating awareness and improving saving culture of the community which are vital to improve their livelihood.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Abebe T (2013). Determinants of crop diversity and composition in Enset-coffee agro forestry home gardens of Southern Ethiopia. J. Agric. Rural Dev. Trop. Subtrop. 114(1):29-38.

|

|

|

|

Ansoms A, McKay A (2010). A quantitative analysis of poverty and livelihood profiles: The case of rural Rwanda. Food Policy 35(6):584-598.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Assan JK, Beyene FR (2013). Livelihood Impacts of Environmental Conservation Programmes in the Amhara Region of Ethiopia. J. Sustain. Dev. 6(10):87-105.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ayele T (2008). Livelihood Adaptation, Risks and Vulnerability in Rural Wolaita, Ethiopia, PhD Thesis Environment and Development Studies, Department of International Environment and Development Studies, Noragric Norwegian University of Life Sciences, UMB, Norway

|

|

|

|

|

Bechaye T (2011). Rural Household Food Security Situation Analysis: The Case of Boricha Wereda Sidama Zone. Msc Thesis. Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia 109p.

|

|

|

|

|

Bedemo A, Getnet K, Kassa B, Chaurasia SPR (2013). Off-farm labor

|

|

|

|

|

Bezu S, Barrett CB, Holden ST (2012). Does the Nonfarm Economy Offer Pathways for Upward Mobility? Evidence from a Panel Data Study in Ethiopia. World Dev. 40(8):1634-1646.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Carswell G (2002). 'Livelihood diversification: increasing in importance or increasingly recognized? Evidence from Southern Ethiopia.' J. Int. Dev. 14:789-804.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

CSA (2014). Population Projection of Ethiopia for All Regions at Wereda Level from 2014 – 2017. Addis Ababa. Ethiopia.

|

|

|

|

|

Degefa T (2005). Rural Livelihoods, Poverty and Food Security in Ethiopia: A case Study at Erensa and Garbi Communities in Oromia Zone,Amhara National Regional State, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Doctoral Thesis,

|

|

|

|

|

Ellis F (2000). Rural Livelihoods and Diversity in Developing Countries, New York, Oxford University.

|

|

|

|

|

Holden S, Shiferaw B, Pender J (2004). Non-Farm Income, Household Welfare, and Sustainable Land Management in a Less-Favoured Area in the Ethiopian Highlands. Food Policy 29(4):369-392.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Khatun D, Roy BC (2012). Rural livelihood diversification in West Bengal: determinants and constraints. Agric. Econ. Res. Rev. 25(1):115-124.

|

|

|

|

|

Lemi A (2005). The Dynamics of Livelihood Diversification in Ethiopia Revisited: Evidence from Panel Data, Department of Economics University of Massachusetts, Boston.

|

|

|

|

|

Nandeeswara Rao P, Bealu T (2015). Analyzing Productivity In Maize Production: The Case of Boricha Woreda In Sidama Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Int. J. Recent Sci. Res. 6(10):6984-6989.

|

|

|

|

|

Nigatu R, Eden M, Ansha Y (2013). Situational analysis of indigenous social institutions and their role in rural livelihoods: The case of selected food insecure lowland areas of Southern Ethiopia, DCG Report No. 73 October 2013, Addis Ababa Ethiopia.

|

|

|

|

|

Soltani A, Angelsen A, Eid T, Naieni MSN, Shamekhi T (2012). Poverty, sustainability, and household livelihood strategies in Zagros, Iran. Ecol. Econ. 79(0):60-70.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

supply decision of adults in rural Ethiopia: Double hurdle approach. J. Agric. Econ. Dev. 2(4):154-165.

|

|

|

|

|

Susuman S, Bado A, Lailulo YA (2014). Promoting family planning use after childbirth and desire to limit childbearing in Ethiopia. Reprod. Health 11:53.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

SZFEDD (2015). Sidama zone finance and economic development department Socio-economic Data, Hawassa. Report, unpublished

|

|

|

|

|

Tegegn GE (2001). Non-Farm Activities and Production Decisions of Farmers: The Cases of Damotgale and Kachabira Woredas in SNPR of Ethiopia. Social Science Research Report Series- No. 15. OSSREA Addis Ababa.

|

|

|

|

|

Workneh N (2006). Determinants of Small-scale farm Household Food Security: Evidence from South Wollo, Ethiopia. Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Dev. Res. 28:1.

|

|

|

|

|

World Bank (2007). Capturing the Demographic Bonus in Ethiopia: Gender, Development, and Demographic Actions. Poverty Reduction and Economic Management unit Africa Region; Report No 36434 ET.

|

|

|

|

|

World Bank (2008). Agriculture For Development: World Development Report. Washington DC.

|

|