The purpose of the study was to assess quality of pottery products produced in Kenyan prisons. The quality of products produced in Kenyan prisons shows lack of standardization. Descriptive research design guided the study. The study areas were Lang’ata and Kisii women prisons with a population of 480 respondents. Purposive sampling technique was used to sample 30 inmates who engage in pottery, thus leaving a total of 450 non-potter inmates who were sampled by use of Krejcie and Morgan’s table. The findings revealed that although pottery products are appreciated by the inmates, majority of inmates do not take part in pottery. The number of elderly inmate potters was low compared to other groups yet the elderly were the ones who passed the skills to the younger generation in the larger society. It was therefore concluded that quality of pottery in prisons exhibited low standard craftsmanship with poor rendition of skills. The study recommended that authorities concerned with prison should work towards promoting the sector by eradicating the negative attitude of the inmates by improving pottery facilities in prisons and incorporate variety of methods and media in order to improve on the products’ aesthetic character. Improvement on facilities may encourage more inmates into pottery, thus assist a large number of inmates to cope with prison environment and reintegration.

Pottery in its totality refers to the type of indigenous wares which are produced by firing clay at low temperatures of 600 to 850°C. They are unglazed, hand-made with simple tools and equipment. Throughout the ages, even before written history, pottery has been used as a medium of expression (Peterson, 2011). Pottery making is a well-known global practice and the most widespread practice of the indigenous people around the world (Kayamba and Kwesiga, 2016). This study looked at quality of pottery products produced in prisons in Kenya as a tool to inmates’ re-entry once released. The study focused on attributes of quality and decorative methods in production of artistic quality of pottery production by women inmates. It is argued in this paper that while pottery as one of the rehabilitative programs carried out in prisons, the production and technology of quality of pottery remain low. The paper argues that with improved standards of quality of pottery produced in prisons, inmates would be equipped with the necessary skills to put in practice once released.

A study by Gukas (2011) on decline of traditional pottery practices in Nigeria affirms that in the new Christian method of education, the schools subjected pupils to be taught the principles and practice of Christian religion alongside other secular subjects such as reading, writing, arithmetic, art subjects such as carpentry, needle work, domestic science, weaving and sewing and variety of new games. The art of pottery was not practically taught by the missionaries. The study shows that the number of traditional potters in the area of study had decreased due to the prevailing contemporary economic, social, political, educational and religious factors that have contributed to the reluctance of the younger generation to develop interest in traditional pottery. Pottery products from prisons displayed in Kenyan shows are few in comparison to carpentry, metal work, beadwork, jewelry, sewing, weaving and others. Good quality carpentry work is produced in Kenyan prisons, unlike pottery products in prisons which exhibit low standard. Through rehabilitation programs in correctional facilities, inmates are imparted with various skills through vocational training programs. These skills include carpentry, joinery, metal work, painting as well as pottery. However, there is notable uptake of pottery compared to other skills. It is upon these that the researcher was inspired to investigate quality of pottery products in prisons in Kenya. The objective of this study was to assess the quality of pottery products in prisons in Kenya.

Adu and Yussif (2017) study carried out in Northern Ghana gave emphasis on identification of concepts of indigenous pottery and noted that African indigenous potters decorate their pottery with tiny roulette, made of wood or string. With this, they use it to create impressions onto the surface of the clay. The aforementioned study was not done in Kenya, the present study which was done in Kenya, looked at different decorations applied on pottery in prisons in Kenya. Pottery as one of the art programs in prisons offer an engaging and humanising option for inmates to engage in the rehabilitative process, thus the need for appropriate decorative skills in quality pottery products.

Pihulic (2005) study that focused on a group of women in Nyanza region, Kenya, emphasized that the vessels in the pit give unique sound when firing reaches the desired stage. Fired pots undergo post-firing treatments which are intended to seal vessels’ surfaces by decreasing permeability, increasing vessel strength, and by making vessel surfaces smooth. Treatments involve the application of substances to both the internal and external surfaces of the pots. Pihulic further notes that finishing in pottery products can impart both aesthetic and functional properties to the vessel. Finishing can affect the aesthetic qualities of a vessel by boosting vessels’ strength and producing smooth and uniform surface. On a functional level, quality of vessels such as finishing can also be used to create a simple textured pattern, making the vessel easier to grip. The aforementioned study was carried out in villages unlike the current study which focused on prisons and specifically looked at quality of pottery products.

Otieno (2009) explored the morphology of different types of fish found in Lake Victoria in Kenya for artistic expression in pottery production and emphasized that the source of artistic expression is as important as the product of expression in captivating the interest and attention of the art consumers. Otieno’s study concentrated on the Lake region in Kisumu and looked at the morphology of fish in production of artistic products in ceramics. The present study picked up from the previous study and covered the whole of Kenya with the aim of finding out the nature of quality products in prisons.

This study was guided by Vygotsky’s Art and Creativity Theory as informed by Lindqvist (2003). The major tenet of this theory is that creativity is the foundation of art and it helps people advance within society by releasing aspects that are not expressed in everyday life. Vygotsky regarded the psychology of art as a theory of the social techniques of emotion. His analysis reflects the artistic process. When the artist creates his art, he gives realistic material an aesthetic form, which touches upon the emotions of the readers and makes them interpret the work of art and bring it to life by using their imagination. An artist works with forms and techniques that have been developed historically and “turned into” art.

The connection between art and life is a complex one, essentially, the aesthetic emotion, brought about by art, creates new and complex actions depending on the aesthetic form of the work of art, which has pedagogical potential, has the power to influence people in the long run. Art releases aspects that are not expressed in everyday life, and it is important tool in the struggle for human existence. Vgyotsky developed his view on the creative consciousness process, the relation between emotion and thought and the role of imagination. He discussed the issues of reproduction and creativity as two aspects that relate to the entire scope of human activity. Vygotsky claimed that all human beings, even small children, are creative and that creativity is the foundation of art as well as for science and technology. This theory has important implications for art in prison and may help further goals of art and creativity. The theory was applied in the study by using pottery as a trigger to inmates’ creative potentials, allow flow and realization of their creative ability and thus enhance positive self-esteem.

Quality of pottery

Demographic characteristics of respondents

In order to better understand the respondents and their suitability, the researcher sought to establish their various demographic and background characteristics. Information on age, education level and duration in prison was therefore captured during the study. This was analyzed and presented in terms of frequencies and percentages as presented in Table 1.

From the findings in Table 1, majority of the inmate potters 14 (51.9%) were aged between 30 and 49 years, seven (25.9%) were aged between 18 and 29 years while six (22.2%) were aged between 50 and 59 years. This shows that nearly three quarters of the inmate potters were aged 30 years and above. Similarly, the researcher sought to find out the age limits of the respondents who were not involved in pottery. From the findings, 57.4% were between the ages of 30-49 years, followed by 50-59 years at 22.8%, 18-29 years was at 12.9% whereas those above 60 years was at 6.9%. There was noticeable correlation among inmate potters and non-potter inmates in that, the highest number of age group as reported in all cases was found to be between 30 and 49 years. This is a clear indication that majority of inmates in prison fall between 30 and 49 years. Being the most active age, inmates can be made more productive if offered adequate skills acquisition for self-reliance, thus contribute to economic growth of the country. The findings show that there were few elderly inmates among the potters, a group that is traditionally known to pass over the skills to the next generation since they are more experienced in pottery making as confirmed by Langenkamp (2000) who argued that it is a common phenomenon among African cultures that craft skills are passed down from generation to generation. This was shared by Edusah (2011) who observed that indigenous pottery industry over the years has engaged the hands of women, who acquired the skills by learning it from their parents. The number of elderly group in prisons was low compared to number of other groups yet the elderly were the ones who passed the skills to the younger generation. This could mean that soon, there might be no one to pass the traditional pottery skills to since the number of the elderly is reducing, yet they are the custodians of traditional pottery. This could contribute to loss of a part of people’s cultural heritage. It can therefore be said that traditional pottery is diminishing in prisons in Kenya and this has compromised the standardization and aesthetic appeal on quality of pottery produced in Kenyan prisons.

In terms of level of education, majority of the inmate potters 11 (40.7%) had primary education with the same proportion (40.7%) also having secondary education as their highest educational qualification. However, five (18.6%) had post-secondary education. This shows that the education level of inmate potters was generally low. Majority of inmates doing pottery was rated at 40.7% who had secondary level of education whereas, 34.2% was recorded for inmate non-potters. A higher proportion 84 (41.6%) of non-potter inmates had primary level of education. There were no holders of university degrees among the inmate potters whereas non-potter inmates had 2.5% having university training. Post-Secondary education was at 18.6% for inmate potters and 17.8% for non-potter inmates. From the findings, all the inmate potters had some form of basic education while 8 (4.0%) of non-potter inmates had no education. The results indicate that the more educated the less number of inmates in prison. This could imply that majority of people who find themselves locked in prisons have low level of education. The low education level could have contributed to a good number of inmates getting involved in crime as a measure of survival and meeting their basic needs. Kayamba and Kwesiga (2016) observe that, given the nature of skills, and the usual undermining of occupations like pottery, has made pottery remain the work of either the large number of illiterate or semi-literate women. Since majority of inmates had low level of education, it was expected that majority of them would have taken up pottery but that was not the case. It can therefore be concluded that even though inmate potters and non-potter inmates had basic education, a good number of them were not in pottery and therefore had not benefited from pottery.

The duration that inmates had been in their respective prisons shows the period over which the inmate potters have had contact with prison pottery production. From the findings in Table 1, majority of the inmate potters 10 (37%) had been in the prison for 1 to 3 years with another 10 (37%) being in the prison for more than 3 years. Thus, 74% majority of the potter inmates had been in the prisons for over 1 year. This gives them ample time to master the craft. The findings show that longer period spent in prison gave inmates adequate time to learn, practice and enhance their creativity in pottery. The findings are supported by Roux (2011) who points out that due to the consistence repetition on the steps involved over several years; the craft becomes motor skill. Likewise, Arthur (2013) contends that pottery is a learned skill transmitted to the select groups of girls and women. Girls raised within the potter household begin to learn how to produce pottery when they are 6 to 13 years old. The learning process starts with informal instruction, which usually last for three years or until the daughter is married. It therefore implies that the longer the duration inmates take in prison, the more they get exposed to production of quality pottery processes such as decoration, design attributes and finishing and firing.

For non-potter inmates, 42.6% were in their 3 years and above jail term, 31.7% were below 1 year and 25.7% were between 1 and 3 years. Thus, non-potter inmates could have experienced the processes and activities involved by joining pottery in the prison because majority of them had stayed in prison for over 3 years. Pottery is one of the visual arts that offer an economic advantage that more inmates could exploit in order to generate income while in and out of prison and assist them to cope with the prison environment. The findings are in line with Sikasa (2015) who noted that the effect of vocational training on women prisoners showed that women who acquired vocational skills such as tailoring, catering, farming skills and knitting had fewer chances of reoffending compared to prisoners who did not have vocational training. Creative activities found in quality pottery products may play a key role in directing the energies of inmates and assisting them to adjust to prison life and life outside prison once they are released, thus the need to encourage more number of inmates into pottery.

Quality of pottery products

Inmates were asked to rate the indicators of quality of pottery products according to their ability. Quality of pottery products produced within the Kenyan prisons was measured using 5 items on a 5- Point Likert scale as Strongly agree = 1, Agree= 2, Not sure = 3, Disagree = 4 and Strongly disagree = 5. The findings were summarized and presented in form of frequencies and percentages as shown in Table 2.

From the findings in Table 2, majority of inmates 20 (74.1%) agreed that they are good in form making but a further three (11.1%) strongly agreed to be good in form making while a further four (14.8%) were not sure. Majority of inmates were good in form. The findings are in agreement with Arthur (2013) who reiterates that the Gamo potters are consistent in how they make each vessel type but there is an individual choice that determines the type of vessels a potter produces such as learning history of each potter, suitable clays, and consumer demands. The fact that Gamo potters have an individual choice of what type of pot to make in terms of form enable them to produce good quality forms that are preferred in the region because of their durability.

Similarly, Kaneko (2013) asserts that unlike architecture and the products of the artistic problem-solving design, handmade pottery provides person-to-person intimacy. The hand of the artist reaches through the object to touch the hand of the user. This creates a bond of friendship, caring and aesthetic gratification that nurtures human life and fortifies it against indifferences. The manipulative nature of clay and functions of pottery makes the product stand out as compared to other artworks. A good pot will be generous of form, its shape asking to be held and its weight reassuringly present in your hands. It can therefore be said that the concept of form as a significant contributor to quality of products obtained through artistic manipulation is a shared factor among potters in different regions of the world.

In terms of aesthetic quality of the products, inmates were found to be generally average (Mean = 3.22 ± 1.121) where majority of the inmate potters 11 (40.7%) strongly agreed that their works met aesthetic attributes while eight (29.6%) agreed that their work met aesthetic attributes. However, only six (22.2%) of the inmate potters strongly disagreed that their products met the aesthetic attribute. Almost half of the inmates strongly agreed that they were good in aesthetic rendition. In other words, majority of them were average in aesthetic rendering in pottery products.

The findings are in line with a study done by Agyei et al. (2018) which found that mixed media method employed could be practised to add value, enhance the texture and aesthetic character and similarly improve the marketability of indigenous pottery. Not only Asante et al. (2013) but other scholars such as Agyei et al. (2018) linked pottery with beauty by stating that the shapes of pots communicate an idea of beauty to both the potter and the customer. Beauty in their studies is linked to pots which are well decorated and have peculiar forms pertaining to the locality. This refers to characteristics such as the shiny outer surface, ringed lines on the rim and neck and the black colour from the smoking process. Traditionally, pots that emerged undamaged after firing are accepted as beautiful. Similarly, Arifin (2015) points out that the modernization process has increased the pots’ appeal with Kaula Kangsar increasingly known as a producer of the best quality products in the country. For the pottery surface to be pleasing aesthetically, finishing attribute such as balance and decorations are of importance in production of charming, interesting pots, a process that inmates can indulge into more deeply in creation of pots with aesthetic appeal. Although inmates were generally good in aesthetic rendition, just a handful of pottery items found their way into Kenyan National shows. There is therefore need for exploration of other media into pottery products in prisons. Exploring with non-conventional materials such as addition of beads and taking keen interest in products’ surface treatment before and after firing may inspire and further educate and enhance inmates’ pottery to meet contemporary expectations.

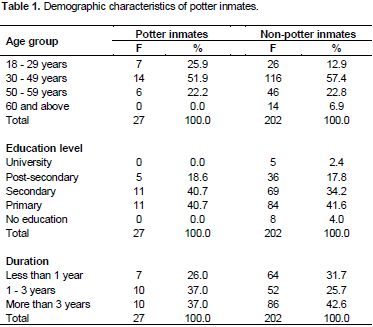

On functional attribute, the study also found that majority of inmates’ strongly agreed that their work met the functional attribute of pottery products (Mean = 3.81 ± 0.834). Although majority of the inmate potters 12(44.4%) strongly agreed that their work met the functional attribute, a cumulative majority 15 (55.6%) disagreed to the fact that their works met functional attribute with 7 (25.9%) strongly disagreeing. Majority of inmates indicated that they strongly agreed that their work met the functional attribute. Kayamba and Kwesiga (2016) note that with the changes in life style, particularly among the educated, there has been an increase in alternative uses of pottery products, in addition to the traditional ones. This has called for innovative activities with urban market. Simonton (2012) shares a similar view by stating that creativity must represent something new or different. But, novelty is not enough; to be creative, there is always an expectation of task appropriateness or usefulness. Similarly, Arifin (2015) adds that the production of pottery by modern methods and with diverse and creative designs has led to more varieties of products like decorative lamps and flower vases. Several pots made by inmates adorned the prison compound; this means that the inmates had the capacity to produce functional items, whose attribute enhances the creative aspect involved in production of quality products. This was visible in the many functional pots used as plant pots placed in different areas at Lang’ata prisons as shown in Figure 1.

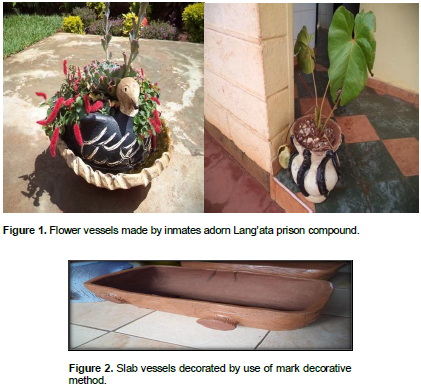

The study looked at the decorative methods in pottery carried out in Kenyan prisons. From the findings of the study, majority of respondents (33.3%) had interest in burnishing method followed by inlaying (22.2%) and application of marks (18.5%). Other methods applied by inmates were excising (11.2%), incising (3.7%), impression (3.7%) and slip trailing (7.4%). The least applied method was graffito method (0%). The findings show that inmates’ application of decorative methods was not diverse. The high number of inmates preferring burnishing affirms to the fact that the only tool for decoration that was available in all the prisons was a burnishing stone used for polishing surface of vessels. Burnishing not only polish the surface but it also strengthens the vessel. The findings are in line with Arthur (2013) who found out that burnishing is one of the most practiced decorative methods among different potters. Different decorative methods on the surfaces of pots serve as design and add beauty to vessels. Inmates should therefore be exposed more to the art of decoration and apply the various methods of surface treatment that pottery offers so that they come up with variety of creative ideas and artistic expressions to enhance their products.

Figure 2 shows a vessel made by inmates with mark method as one of the decorative treatments. Close observation of the vessel reveal cracked lines along the side of the vessel. Such types of vessels with several cracks on display which were common at the showroom at Lang’ata prison may not attract customers. Vin (2007) pointed out that Waimea potters believed that their work sold easily because they had established high standards and their pottery had a unique quality to it. Concurrently, Pihulic (2005) mentions that Kinda e Teko group carries out quality assurance protocols that extend beyond casual visual inspection in that before the group will allow a vessel to be sold at market, proof testing is carried out. The group test is to ensure the vessel is capable of holding water for a week. Defects such as cracks on the vessel exhibit lack of aesthetic appeal and the surface may compromise the strength of the vessel that may result in breakage.

Inmates should be assisted to produce items of high standards. It was evident from the items made by inmates that procedures for sealing or testing of products were not adhered to in prisons. The lack of pottery vessels in the Kenyan National shows could therefore be attributed to poor workmanship in pottery products.

Figure 3 photograph shows one of the inmates apply burnishing method on a vessel using a polishing stone. The figure corroborates the findings in Table 2 which show that burnishing was the most preferred method of decoration among the inmates. The findings were in line with Arthur (2013) who postulated that burnishing is one of the most practised decorative methods. The use of various surface decorations should be more intensified.

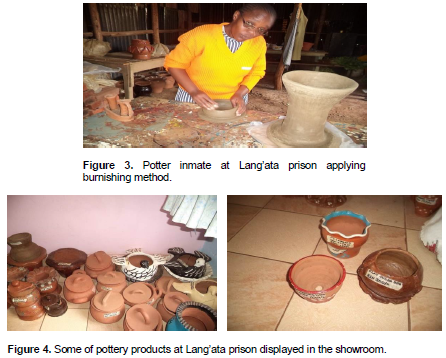

Figure 4 shows works done by inmates and some of the items show designs derived from animals and plants. The pottery shows elements of creativity in terms of decorative abilities and the use of visual imagery that need to be enhanced. Pots made in prison are majorly for aesthetic purposes and to keep inmates engaged, therefore the need for eloquence of form and fine finishes of products. A study by Otieno (2009) on exploration of morphology of different types of fish found in Lake Victoria emphasized that the source of artistic expression is as important as the product of expression in captivating the interest and attention of the art consumers. Inmate potters seemed to derive their designs from natural plants as shown in some of the products in Figure 4. It was also observed that in all the two prisons, all the pottery items were displayed on the floor, both prisons had no shelves for display of pottery items. Display shelves are necessary for pottery products because it cushions the products from breakage and customers are able to view the products with ease when displayed on shelves as opposed to when displayed on the floor. Pottery items are delicate and should be stored or displayed on shelves to avoid breakage. On the same note, Digolo (1999) suggested that shelves to be used in the art room may vary in shape and size but should be adequate as storage facilities. Similarly, Eames (2009) confirms this by stating that placing items on shelves increases their longevity, attracts more buyers and instills organization among prison potters. This was not the case with the storage in both prisons. Kisii prison had their pottery stored in a squeezed tiny room with very poor lighting. In Lang’ata prison, the showroom had no shelves for pottery storage. The items were all placed on the floor. This is risky as pottery items are brittle and can break easily. This indicates lack of attention to pottery products which could hamper its uptake. Display of pots on shelves would increase marketability of pottery in prisons. Other items made by inmates such as jewelry, sewn materials and woven items were neatly displayed on shelves.

Having established the responses from the inmate potters, it was important to further look at the quality of facilities in pottery section in the two prisons (Table 4). The study established that the poor or very poor quality of pottery facilities was not only specific to a particular institution but was a generally similar problem in Lang’ata and Kisii prisons as shown in Table 3 where majority (77.8%) rated the facilities as poor and (22.2%) rated the facilities as very poor in Lang’ata prison and in Kisii prison (66.7%) rated facilities as poor and 33.3% as very poor. Moreover, Kisii Prison did not have a kiln but were using open firing place for their products. Long term exposure to pottery dust from open firing may have cumulative effects and result in health problems. Carbon monoxide from fuel-fired kilns is also highly toxic. This can cause oxygen starvation through inhaling (Asante et al., 2013). On a similar note, Kwasiga and Kayamba (2016) notes that local potters use open bonefire to harden their wares, methods which may not give the right firing range of the wares. Their products may not withstand the wear and tear compared to the ones fired in kilns. It was observed that the kiln at Lang’ata prison was situated at a close range to the iron roofed pottery workshop. The close proximity makes the workshop extremely hot, a situation that is not conducive for learning and could have health repercussions on inmates and staff who use the workshop in the long run. This has a strong influence on pottery production in the long run and can contribute negatively to its productivity. This could be one of the reasons for low standard of pottery products produced by inmate potters. Modern kilns by gas or electricity are easy to control than wood and allow shorter time to be used. It can be said that the Lang’ata prison is better off in terms of facilities given, because it had a kiln that uses wood for firing as opposed to Kisii prison which did not have a kiln. There is need to switch to modern mode of production like use of a gas kiln in order to improve on the products’ aesthetic character and enhancement of texture. This will go a long way in encouraging inmates to take up pottery practice.

The study sought to establish the extent to which inmates who do not engage in pottery appreciate pottery products. The findings were summarized and presented in Figure 5.

The study found that almost all the non-inmate potters (92.1%) appreciate pottery products. This shows that inmates acknowledge the beauty and function of pottery products. One non-potter interviewee indicated that: “If I would have shown interest in the course in the initial stage, I would have made beautiful pots out of that opportunity” (Non-Potter Inmate open-ended response)”

Another inmate remarked that: “There are many uses of pottery at home, my mother use them as decoration in our living room” (Non-Potter Inmate open-ended response).

It is clear from the aforementioned statements that pottery is appreciated not only because of it functionality but also its aesthetic appeal. Despite the high percentage of pottery’s appreciation by non-potter inmates, the extent of involvement in production of pottery products is very low among inmates, this could be attributed to negative attitude and perception towards clay work such as clay being seen as a dirty material with low income capacity. On another hand, Kaneko (2013) states that unlike architecture and the products of the artistic problem- solving design, handmade pottery provides person-to-person intimacy. The hand of the artist reaches through the object to touch the hand of the user, creating a bond of friendship, caring and aesthetic gratification that nurtures human life and fortifies it against indifferences. The feeling it creates when held and function experienced in pottery makes the product stand out as compared to other artworks. Perceptions and negative attitude are likely to affect the industry for a long time if no concerted efforts are made to correct the situation.

Perceptions on pottery among non-potter Inmates

Perception in pottery can affect its delivery in various ways. It was important to find out non-potter inmates’ feelings, views and opinions towards pottery. Several themes emerged from non-potter inmates on perception of pottery including - skills development, pottery as an old art activity is dirty, it is mostly practised by the elderly, it is a low income activity, it is for less intelligent people, it is tedious and difficult.

During an interview with the non-potter inmates, one of the inmates indicated that pottery was for the old and was not relevant to the modern generation: “Pottery is for old generation, it is dirty and it does not excite me” (Non-potter inmate open-ended response).

Another non-potter inmate stated that: “Pottery involves a lot of work, it is dirty and done in squeezed room. Sometime inmate potters stay idle because of lack of clay” (Non-potter inmate open-ended response).

One non-potter inmate also stated that: “I do not think I can make good money out of pottery” (Non-potter inmate open-ended response).

The findings on reasons for lack of interest in engaging in pottery indicates that, among the factors that discouraged the inmates was inadequate clay and facilities, and negative attitude towards pottery. From the findings, it is clear that some of the non-potter inmates consider pottery as a tool for material gain only. Some of the inmates felt that pottery is not lucrative in terms of money earned from its sale. This finding corroborates Mbogori (2016) study who observed that an African child is socialized to be ashamed of traditional values, as a result, the traditional technologies like pottery making, are now left in the hands of the elderly. Consequently, master potters have no one to pass the skills to, leaving the craft without successors. This view is shared by Iroegbu (2017) who stated that, due to the negative attitude of some parents and students towards skills acquisition, there is the urgent need for the director in charge of school services and other stakeholders to embark on programmes that highlight the benefits of skills acquisition training so as to embark on skills acquisition training programmes in order to encourage the interest of both parents and students to the programs. Similarly, Arifin (2015) emphasize that the younger generation show disinterest in family pottery production that requires high level of skills, diligence and hard work while the economic returns are uncertain. As a result, traditional hand-made pottery makers are finding it difficult to get those who could inherit the skill. This is a drawback that could jeopardize its continued existence. These views can be said to have contributed to low number of inmate potters. The aim of pottery activities in prison is to train inmates on skills for self-reliance and use pottery as a form of recreation. Moreover, identification with an activity other than ‘prisoner’ like pottery making is vital for the inmates’ state of mind when reintegrating into society.