Review

ABSTRACT

Dances are part of our socio cultural identities in Nigeria. They are performed for different purposes and at different settings such as home, social gatherings, religious centres, schools, concert halls, dance halls and theatres. Some dance steps are peculiar to certain ethnic groups within each geo-political zone in Nigeria. These peculiarities of dance steps are seemingly going into oblivion. This paper seeks to find out reasons for the erosive state of these dance steps and reasons for the consequent emergence of modified dance steps. Primary data were collected through oral interview of selected dance groups in Ile-Ife, Ibadan, Ijaw, Calabar, Istekiri and Jos metropolis. Secondary data were collected by reviewing works of scholars in published books and articles from national and international journals. The findings reveal that the emergence of modified dance steps has now become an accompaniment to popular music as against the conventional concept of music as an accompaniment to dance. These dance steps become more popular than the traditional dances and adapted as homely dances in all the selected geo-political zones in Nigeria. The paper concludes that the emergence of modified dance steps has eroded and sniffed the dance peculiarities of these towns as a result of popular music artiste’s quest for identity and unity of dance steps to their music.

Key words: Appraisal, evolution, dance, accompaniment, popular music.

INTRODUCTION

Dance in the African context can be classified into traditional, modern and contemporary dances. Traditional dances are those dance steps that are created from local and indigenous ingenuity. Modern dances involved dance steps created from individual’s or groups’ creative ingenuity while contemporary dances are those dance steps modified from traditional dances that are presently in use. From the trajectory of music and dance in Nigeria, music has always been seen as accompanying dance but somewhere along the line, dance is beginning to revolutionise in line with the “theory of dance autonomy”; according to Aluede and Eregare (2006) that “dance scholars in our contemporary societies hold the view that dance is a separate art form devoid of all other ancillaries”. Jacqueline (1989) defines dance as “movement in time and space”. Aluede and Eregare (2006) further posit that “although, the origin of dance is believed to be as old as man, its origin is lost in antiquity; it is however believed to be of divine origin”.

Dance is generally accepted in every Nigerian society as an integral component of its existence. Everyone in each society is culturally conscious of his or her traditional dance; which is more or less the person’s mark of identity. In this regard, dance is not seen merely as an aesthetic or artistic endeavour, but as a way of life or the actual life of the people. In fact, Nigerian traditional dances are not complete without the functions of such cultural nuances which have helped, to a greater extent to characterise or describe the indigenous Nigerian dances in proper perspectives. The culture of the people is therefore represented in these dance steps and, or presented in its authentic state. The nature of Nigerian dance can therefore be recognised through the cultural behaviours of the people; these include spiritual, ceremonial, social, political, occupational, educational, entertainment and recreational ethics. All these are often displayed in dance steps. The emphasis on these cultural undertones indicates that the paper is guided by the theory of social sciences; the discourse is therefore, to a large extent, a socio-cultural one as expressed in the creational dance ability of popular music and its resultant effects in creating a unity of dance steps among Nigerians in the 21st century.

AN OVERVIEW OF DANCE IN NIGERIA

Nigerian dances in its origin have been described by many scholars such as Layiwola (2000) as ‘speculative’, given to forming conclusions or opinions that are not based on fact. In Clark’s perception, Nigerian dance has a ritual origin. Clark informs that the origin is from “early religious and magical ceremonies and festivals of the Yoruba, egwugwu and mmo masquerades of the Ibo and the owu and oru water masquerades of the Ijaw” (Clark, 2000). Two other scholars supporting the ritual origins of dance are Okoye (2000) who sees it as “primarily ritualistic” and Mbiti (1990), who notes that Nigerians are deeply religious in their ways of life, including dance. The interaction between the corporeal and the incorporeal worlds through dance is expressed by Monyeh (2007) that:

Dance is an avenue for total expression of the natural and the supernatural. A masquerade in its performance communicates to the living and the underworld. In this case there is the relationship with the world of the living and the world of the spirit. The body could make the invisible concrete thus creating a completely self-contained world for dancers in which they can perform physical feats and prowess which are far beyond normal daily occurrence or normal movement” (Monyeh, 2007: 111).

Other scholars, apart from observing Nigerian dances as spiritual, are of the view that it is a total expression of the life of a people. Akunna (2007) reviews this as “a manifestation of the socio-political, economic, religious and aesthetic life of the people”. For Harper (1968), “dance is an integral part of life”. In another argument, Asante (1996) goes beyond reviewing Nigerian dance as an integral aspect of life to seeing it as life itself. Buttressing this view, Enekwe (1991) expresses that man is able to communicate with his kinship, his community, and even with his environment through dance. Dance in Nigeria, according to Ojuade (2002), begins with the birth of a child which “elucidates dancing activities of joyful movement”. Ojaide (1992) refers to this as a symbolic communal renewal and revitalisation. Harper (1968) notes that the child, while developing to maturity is celebrated with different songs at different stages; she further states that dance plays a cathartic role during the key transition from one social state to another: a child is welcomed into the community at his naming ceremony; an adolescent is initiated into the responsibilities of adult life. Kofoworola (1984) describes Nigerian dances as a socio-religious activity where the people engage in communal ceremonial activities. Graft (1976) equally endorses Beier’s and Kofoworola’s position of dance as a socio-religious function when he states that:

‘The ritual dance always takes place at night. It is preceded by sacrifice and accompanied by praise songs and prayer. It culminates in the appearance of Efe, a powerful mask, preceded by a young girl who carries a witch in the form of a bird in a calabash; the dance that usually follows the next afternoon is more interesting for the avowed purpose of this dance is to provide entertainment to the witches and keep them in good temper, and of course, at the same time entertain the townspeople at large who had been excluded from the night ceremony’ (Graft, 1976).

However, it is not an overstatement to point out that Nigeria dances perform several other functions than as stated by earlier scholars. It is in this connection that Harper (1968) states that Nigerian dance fulfils several functions simultaneously apart from the social and religious. However, there is always one overt function on which other subsidiary functions depend. These several functions described by Harper include: “Religious, ritual or ceremonial; expression of a pattern of social organisation; expression of political hierarchy or organisation; economic or occupational; expression of history or mythology; educational; recreational and entertainment”. In another argument, Nigerian dances serve as a tool for social interaction. Enekwe (1991) corroborates this feeling of togetherness where members understand themselves and express a sense of solidarity when he posits that:

‘The beauty of Nigerian dance lies in its combination of purposefulness and high aesthetic concern, its celebration and reflection of communal life and virtue, its seeking to unite the dancer with the dance, its embodiment of the collective beliefs and symbols, which constitute both the structure and content of the art, and its ideal frankness and intensity of expression’

In another purview, Adeoti (2014) laments that dance has never been taught as a separate course of study in Nigerian schools and colleges. It has always been part of the Department of Theatre, Performing Arts, Creative Arts and other of such names. Adeoti further writes that:

in the Nigerian university system, starting with the University of Ibadan which floated the first school of drama in 1963, dance has existed as a subject/course/ specialization within Theatre Arts, Dramatic Arts, Creative Arts, Performing Arts, English and Literary studies, African Studies, Cultural Studies and so on (19). Writing about the state of dance studies in Nigeria

Complementing the above position, Bakare and Onyemuchara (2016) opine that “the greatest problem confronting the art of dance and choreography in Nigeria today is teaching”. Peaking on the same subject matter of dance scholarship, Igbinleye (2015), a professor of language of the Federal University Lokoja, eulogized the students after the performance in these words:

The hallmark of a good dance performance is being able to involve all body part in the enactment. Choreography is practical and seamless; the ease of rendition is engaging and involves the audience in an otherwise difficult and complete act as if it is an everyday common place performance. Every successful dance elicits and evokes feelings of elation, fulfilment and satisfaction, but it does not immediately show the discipline and practice that had gone into the preparation. All your performance tonight shows discipline, tutorship, learning and uncommon passionate commitment to excellence. The dexterity of your drummers is worthy of adulation and celebration (Recorded speech).

In another opinion expressed by Adedeji (1966), in tent pitching with Enekwe (1991) emphasises that the cultural and functional properties of Nigerian dance “stretched beyond the aesthetic”. It is in the light of this that Clark (1981), and Ògundejì (2000) argue that there is nothing such as dance for dance sake in Nigeria. Dances are always done with utilitarian motives and not for overt “aesthetic enjoyment”. The utilitarianism of Nigerian dance lies in the coded movements and symbols executed by the dancers which are readily found within the culture of the people and it is in satisfying value that the utilitarian objective of the aesthetics is appreciated. This expressive characteristic of Nigerian dance makes it a very vital tool for communication in the society.

OCCUPATIONAL DANCE IN NIGERIA

This is mostly performed through occupational ethics and involvement. It is normally observed by professionals as a form of relaxation and entertainment after a hard day’s job. They use this dance form to demonstrate the nature of their profession with the aim of amusing themselves. Such is the case with the popular Swange dance which developed from songs and dances the farmers used in entertaining themselves at leisure. It is interesting to note that movements associated with different occupations have been developed into full-fledged dance performances. Harper (1968) describes some of these performances in Nigeria with references to Nupe fishermen who are renowned for their net throwing and which was formalised into dance patterns. Also, young Irigwe farmers on the Jos Plateau leap to encourage the growth of crops at festivals related to the agricultural cycle. Occupational guilds and professional organisations of experts, such as blacksmiths, hunters, or wood-carvers have their own expressive dances. Hunters may re-enact their exploits or mime the movements of animals as a ritual means of controlling wild beasts and allaying their own fears, all these have been developed into various dance steps in Nigeria today. This development has also made it possible to recognise, even at a glance of any of the dances in performance, the occupational affiliation of such dance.

DANCE AND MUSIC RELATIONSHIP OF NIGERIAN POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE

Various definitions have been given to Nigerian dance which include various expressive modes. Osanyin (1998) sees dance as an incorporation of music, dance, poetry, masking and topicality; in this vein, Adedeji (1966) notes Nigerian dance as the inclusion of mimetic masks, chants, song, gesture, costume, myths, legends, folktales, sculptures and other artistic manifestations. Nigerian dance in the 21st century has been defined as an art that is always influenced and complemented by musical activities. Scholars such as Aluede (1999) have affirmed that Nigerian dance cannot exist without its correspondent musical accompaniment. Esilokun (1991) states that the Nigerian society uses “music and dance to incite or to exhibit emotion”. Another emphasis was expressed by Enekwe (1991) on the practice of the musicians and dancers who apply every necessary step to ensure that their relationship is ever cordial during any dance experience.

While the dancer is encouraged by the rhythm of the musician, the musician in turn ensures that the music does not contradict the steps and movements of the dancer. Popular music in Nigeria is currently on the premise of Enekwe‘s postulation on the practice of music creating a dance step. Before now, dance to musical works had always been a free dance, created by the dancer, to any kind of music but, with the emergence of popular music, musical artists have been able to create a dance step that is specifically designed for a particular music which has hitherto broken the barriers of unity of dance steps.

NIGERIAN POPULAR MUSIC AND CONTEMPORARY DANCE NOMENCLATURE

Dance is a very important part of the Nigerian way of life. Conventional wisdom has it that every Nigerian can dance. There are two broad categories of dance in Nigeria; traditional and contemporary. Traditional dances, basically, are all the formal and informal dance moves, steps, patterns and practices that have been passed on to this present crop of Nigerians by our ancestors. Every Nigerian tribe has its peculiar version or variation of this dance and it comes with intrinsic meaning for the people who have it. For example, Igbo youths in Eastern and Southern Nigeria dance a very vigorous acrobatic dance called Atilogwu and Tiv dancers do the Swange or the Cat Dance. Similarly, the Yoruba dance the Bata Drum beats while the Fulani man’s stick dance is unique and traditional to him.

Another aspect of Nigerian dance is the contemporary dance which is the discourse of this paper. Were you to walk into a Nigerian club or party, you would not see a lot of people dancing the traditional steps. What you would see is what we have come to refer to as contemporary dance. It is a fusion of western dance styles and traditional dance styles as well as various self-expressionism dance moves. Some of these moves are simply modern forms of traditional dances like etigi which came from one of Calabar’s traditional dances. Others like the alanta and skelewu are the offerings of popular musicians expressing themselves and giving their listeners an opportunity to do same. There is, of course, the ever present western style hip-hop dance moves all remixed to give them a Nigerian flavouring.

If you get the opportunity to attend any Nigerian party, then keep your eyes open for the informal dance competition which always springs up. Nobody wants to be outdone at the party and it is all done in a spirit of fun. It is especially interesting at the reception of weddings to watch bride and groom put their dance skills to the test. Not to mention the general fun of everyone dancing at the ceremony. However, there are popular contemporary dances in Nigeria that are commonly danced at every social gathering with no barriers to age or sex, learned or illiterate, tall or short, slim or fat, even this trait is extended to the blinds. Some of these dances are listed below:

i) Galala by Daddy Showkey

ii) Suo by Mountain Black and Mad Melon

iii) Alanta by Artquake

iv) Makossa by Olomide Awilo Longomba

v) Azonto by Wizkid

vi) Etigi / Kukere by Iyanya

vii) Skelewu by Davido

viii) Shoki by Dre San, Lil Kesh and Orezi

ix) Sekem by MC Galaxy

x) Shakiti Bobo by Olamide

Dance as an accompaniment to popular music

The purpose of dance for music is different from that music for dance. Dance is movement and this is very obvious. A series of pretty poses in a dance does not really impress an audience but how a dancer moves into and out of those positions in an accompaniment to music makes an audience sit up and take notice. The flow of the movement, the physical peaks and valleys in relation to the music is a large part of the visual stimuli to which an audience reacts. In ages past, music has been a stimulus for developing different dance styles and techniques; in other words, music has been a source of accompaniment to dance practices. In recent times and with the development of ‘dance attachment’ to a particular popular music by musicians as a selling point in the Nigerian music industry; dance has been a viable instrument which has equally been applied very effectively to serve as an accompanying factor to popular music. Beyond the music for which these dances have been created, these dances could as well be adapted to accompany other popular music. These popular music tracks are made acceptable to a greater number of people not because of the lyrical contents of the rhythm of the music, but as a result of the various dance steps involved in the performance of the music. It should also be of note that the musical tracks are known, recognised and danced through the dance style nomenclature. It should also be noted that the function of dance as an accompaniment to popular music breaks gender limitation because both sexes are usually involved in the process of using dance to accompany music. Dance accompaniment to music has gone beyond age barriers as well, young couples use dance to accompany music during wedding reception and old couples use dance to accompany music during wedding anniversary. Nigerians love to dance and it is on this note that every Nigerian popular artist tries to create a new dance step for his or her fans in order to keep their music alive forever. This paper observes ten (10) popular music dance steps and effects on Nigerians.

Galala by Daddy Showkey

This dance step which was associated with “the ghetto” or Ajegunle, Lagos was made popular by dance hall/highlife singer, Daddy Showkey in the mid to late nineties. The song grew in popularity with the rise of “ghetto” acts like Daddy Fresh, Baba Fryo, Danfo Drivers, and African China. Although many artists have claimed to be the originator of the funny dance step that includes weird facial expressions and body distortions, this has not derailed from its enjoyment. A variation of the dance steps is expressed in Figure 1.

Suo by mountain black and mad melon

Suo also a “ghetto” dance overthrew Galala to become the hottest thing in the late nineties but unlike Galala, its reign was brief. It was made popular by Mountain Black and Mad Melon aka Danfo Drivers on their hit single, Danfo Driver. Figure 2 expresses the dance step.

Alanta by Artquake

Alanta was as weird as Galala; characterised by “winch face”; dancers raise their legs, one after another beating an imaginary drum on their stomach. It was made popular by Artquake. Figure 3 expresses the dance step:

Makossa by Olomide Awilo Longomba

This dance step is known in Nigeria as Makossa; it is actually based on the Congolese Soukous. It was made popular in Nigeria following an influx of Francophone songs by Koffi Olomide, Awilo Longomba and others in the late nineties and early twenties. One may argue that popular dance steps that followed the Makossa craze were inspired by its strong rhythmic force. Figure 4 expresses the dance step.

Azonto by Wizkid

Azonto became popular in Nigeria through the Ghanaian singer, Fuse ODG with his song Azonto featuring Tiffany. It gained more popularity when Wizkid spits on its beat in one of his freestyles and when the video above went viral, gaining more views than even the official video by Fuse. It has gone on to become one of the greatest dance movements in the last decade, spreading from Ghana to other African countries and Europe. Figure 5 expresses the dance step.

Etigi / Kukere by Iyanya

Etigi became popular when Iyanya released the video for his hit single, Kukere. It is actually an Efik people of Cross Rivers State’s traditional dance move that was modernised. Figure 6 expresses the dance step.

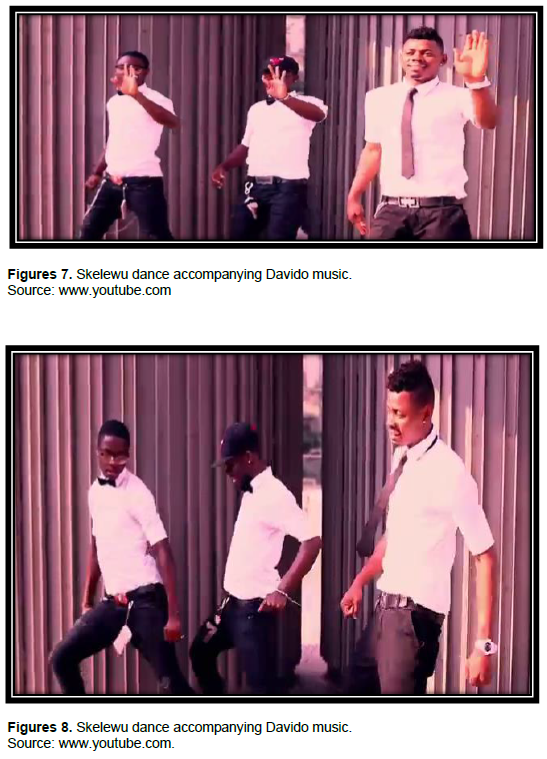

Skelewu by Davido

Davido came up with this dance step in one of his musical tracks and wooed everyone with this hit single, Skelewu, and followed it up with a beautiful dance step to promote the song. The song gave the Nigerian artist recognition home and abroad, memorable of which was when it was played during the half time of a Spanish La Liga match in 2013. Figures 7 and 8 express the dance steps.

Shoki by Dre San, Lil Kesh and Orezi

Shoki will be remembered as one of Nigeria’s most controversial dance steps because about three acts claimed to be its originator, Dre San, Lil Kesh and Orezi. Leaving the originator issue behind, Shoki was a hit, considering how easy it is. Figure 9 expresses the dance step.

Sekem by MC Galaxy

Sekem dance and dancers are lovely to watch. The jolly sideways, back and forth moves is the beauty of the dance step created by MC Galaxy on his hit track Sekem. Figures 10 and 11 express the dance steps.

Shakiti Bobo by Olamide

In what looked like a mere freestyle when it was first released, Olamide’s Shakiti Bobo became a monster hit when its visuals were released with a trending dance step that many embraced with both arms. Shakiti Bobo became so famous that worshipers made its moves at churches across the federation. Figure 12 expresses the dance step.

It is inadvertently becoming cultural bound for Nigerians to quickly switch to a particular dance step at a particular moment in time when certain popular music is on the air (radio, television, DJ player or from cell phones). Through a careful observation of dancers at parties, it was concluded that contemporary dance in Nigeria has adopted a unified step for a particular popular music which has been created by the artist of such music to hypnotise fans into dancing no other dance than the one created by the artist. Through this process, a unity of dance step has been adopted and it is danced to such music anywhere and at any time such music is played. This adoption is not limited to within Nigeria but has also been globally accepted. It has also been observed that whenever Daddy Showkey’s music ‘fire, fire’ is played, it is expected that Galala dance will accompany such music. This observation has been established for Suo by Mountain Black and Mad Melon, Alanta by Artquake, Makossa by Olomide Awilo Longomba, Azonto by Wizkid, Etigi / Kukere by Iyanya, Skelewu by Davido, Shoki by Dre San, Lil Kesh and Orezi, Sekem by MC Galaxy and Shakiti Bobo by Olamide.

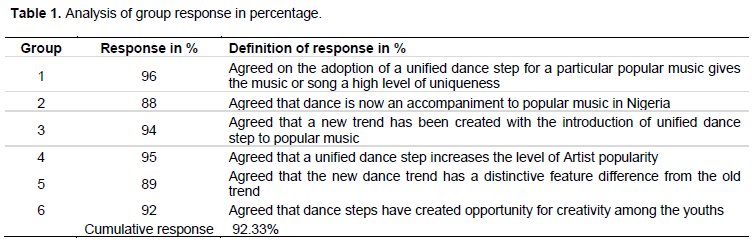

Findings from the interviews conducted show that the artiste decides the type/kind of dance should be performed to the music as against the former practice that have the Artiste – Music – Dance and the current trend which is Artiste – Dance – Music. It is believed that any dancer who deviates from the artiste structured dance steps as accompaniment to the artiste music is regarded as being dance deviant. Dance is seen as controlling the music which is in line with the theory of dance autonomy as postulated by Aluede and Eregare (2006) that dance scholars in our contemporary societies hold the view that dances is a separate art form devoid of all other ancillaries. Below is the quantitative analysis of the responses of the dance groups in the selected cities in South-western Nigeria (Table 1).

CONCLUSION

In this paper, attempts have been made to discuss views of scholars on dance, factors that propel dance and values of such to the Nigerian society. The paper also traced the various dance steps in contemporary hip-hop music in Nigeria. The paper went further to project the various dance steps that have resulted from the emergence of popular music in Nigeria. These contemporary dance steps were also pictorially presented for the purpose of image concretisation. The paper therefore concludes that there is a paradigm shift in the concept of Nigerian dance steps especially from traditional to contemporary with the emergence of popular music which has changed the concept of dance practices. Both music and dance share the tendency to have events uniformly spaced in time, proceeding by what is coined as isochronicity (Dean et al., 2010). People, in fact, can move together in synchrony, but this requires temporal anticipation and entrainment. It seems, further, that amongst animals only humans can generate and align with a regular pulse, be it musical or bodily (Patel, 2006; Wallin et al., 2000). As such, music can favour the formation of coalitions and promote cooperative behaviour toward group members through the opportunities that it offers for the formation and maintenance of group identity, group synchronization between members of a group, and group catharsis or the collective expression and experience of emotion (Brown, 2000).The paper concludes firstly, on the premise that dance is now serving as an accompaniment to music rather than music accompanying dance in the 21st Century Nigeria popular music practices; secondly that traditional African dance steps are being eroded by the emergence of modified modern dance steps which result from the modern artiste quest for identity. This paper has implications on society, culture, music industry, policy makers.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The author has not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Adedeji J (1966). The place of drama in Yoruba Religious observance. Odu: University of Ife Journal of African Studies 3(1):88-94. |

|

|

Adeoti G (2014). The Dance art in the forest of a thousand troubles. Dance Journal of Nigeria 1(1):1-23. |

|

|

Akunna (2007). Creativity and the African (dance) theatre: towards a united essence. Perspective in Nigerian Dance. Ed. C. Ugolo. Ibadan: Caltop Publications pp. 15-25. |

|

|

Aluede CO (1999). African music and dance: Any different. Journal of Advanced Research in Education 3(1):87-98. |

|

|

Aluede CO, Eregare E (2006). Dance Without Music: An Academic Fable and Practical Fallacy in Nigeria. The Anthropologist 8(2):93-97. |

|

|

Asante WK (1996). African Dance: An Artistic, Historical and Philosophical Inquiry. African World Press Trenton. New Jersey. |

|

|

Bakare RO, Onyemuchara CE (2016). The development of dance art within the nation's pop culture: a study of selected trending dance moves in Nigeria. Lwati: A Journal of Contemporary Research 13(3):152-169. |

|

|

Brown S (2000). Evolutionary Models of Music: From Sexual Selection to Group Selection. Perspectives in Ethnology 13(13):231-281. |

|

|

Clark JP (1981). Aspects of Nigerian Theatre. Drama and Theatre in Nigeria: A Critical Source Book pp. 57-74. |

|

|

Clark SC (2000). Work-family border theory: a new theory of work-family balance. Human Relations 53(6):747- 770. |

|

|

Dean R, Byron T, Bailes F (2010). The Pulse of Symmetry: On the Possible Co-Evolution of Rhythm in Music and Dance. Musicale Scientiae Special issue 2009-2010. pp. 341-367. |

|

|

Enekwe O (1991). Theories of Dance in Nigeria: An Introduction. Nsukka: Afa Press, Print. |

|

|

Esilokun KO (1991). The arts of communication in the American and Nigerian societies. Ibadan Journal of Humanistic Studies. No.6. Ed. B. Folarin. Ibadan: Faculty of Arts, University of Ibadan. pp. 54-65. |

|

|

Graft J (1976). Roots in African drama and theatre." African Literature Today: Drama in Africa. No. 8. Ed. E. D. Jones. New York: African Publishing Corporation pp. 1-24. |

|

|

Harper P (1968). Dance studies. African Notes. Volume 4 Number 3. Institute of African Studies, University of Ibadan, Nigeria. |

|

|

Igbinleye G (2015). Commendation Speech. NUC Accreditation Team Command Performance. Federal University Oye-Ekiti Auditorium. |

|

|

Jacqueline B (1989). Time and History in Nuruddin Farah's Close Sesame. The Journal of Commonwealth Literature 24(1):193-206. |

|

|

Kofoworola Z (1984). The impact of drama in the Northern States of Nigeria. Nigeria Magazine 151:30-39. |

|

|

Layiwola D (2000). Yoruba tragic drama: a note on the origins of Nigerian theatre. Rethinking African Arts and Culture. Ed. D. Layiwola. Cape Town: The Centre for Advance Studies in African Society pp. 129-136. |

|

|

Mbiti JS (1990). African religions and philosophy. Heinemann. |

|

|

Monyeh PM (2007). Dance and National Development. perspectives in Nigeria Dance Studies, Ibadan; Caltop publications. pp. 106-115. |

|

|

Ògundejì PA (2000). Ritual as theatre, theatre as ritual: The Nigerian example (Vol. 2, No. 1). Ibadan Cultural Studies Group, University of Ibadan. |

|

|

Ojaide T (1992). Modern African literature and cultural identity. African Studies Review 35(3):43-57. |

|

|

Ojuade J (2002). The secularization of Bata Dance in Nigeria. Nigerian Theatre Journal 7(1):55. |

|

|

Okoye C (2000). Form and Process in Igbo Masquerade Art. Thesis of the department of Theatre Arts, University of Ibadan, Nigeria. |

|

|

Osanyin B (1988). The concept of the African total theatre and its implications for African Unity. Section IV-Literary Traditions. African Unity: The Cultural Foundations P 153. |

|

|

Patel A (2006). Musical Rhythm, Linguistic Rhythm, and Human Evolution. Music Perception 24(1):99-104. |

|

|

Wallin NL, Merker BM, Brown SB (2000). The origins of music. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press pp. 389-410. |

|

Copyright © 2024 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article.

This article is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0