Full Length Research Paper

ABSTRACT

This article reflects on the artistic research that originated the video-performance Entre voos e quedas. In this research, the interaction between the authors during the creative process is discussed anchored on a perception-action perspective, even when the authors were apart during the COVID-19 pandemics. Also discussed is how our creative approach is anchored in a multi-modal perspective. This is because visual and sound perception and visual and sound elements were connected from two environments, approaching the concept of affordances.

Key words: Creative process, artistic research, intertwined hierarchy, affordances, video-performance.

INTRODUCTION

This article reflects on the creative process of Entre voos e quedas, an artwork involving music, dance, and circus within an interdisciplinary context. Entre voos e quedas (in English: “Between flying and falling”) is a video-performance inspired by flying scenes filmed on an aerial setting and falling ones shot on the ground. The creation was triggered by the fall of an apple, through which the dancer and the aerialist dramaturgically interact. It is a video performance created with the participation of a dancer, an aerialist, a composer, and musical interpreters, all apart due to the pandemic. The dispositional states of two different remote environments are gathered in Entre voos e quedas, both recorded on video and integrated by the musical composition, bringing together video, dance, and soundscape. The theoretical reflection presented here considers the Theory of Perception-action (Gibson, 1950, 1951, 1959, 1961). The creative approach is discussed in this way, anchoring it in a multimodal perspective, linking visual and sound perception and elements from two environments. The interaction between the authors during the creative process is an object of reflection, tied to a perception-action perspective, even when the authors were apart.

The study discussed how the elements of Entre voos e quedas have unfolded together. Thus, “design” is considered in an expanded perspective, a design that spreads to other artistic areas. In this sense, it does not only refer to the set of objects, theories, and conceptions grouped under the design definition as a knowledge area. Music, choreography, and video graphics compositions can be viewed as designs.

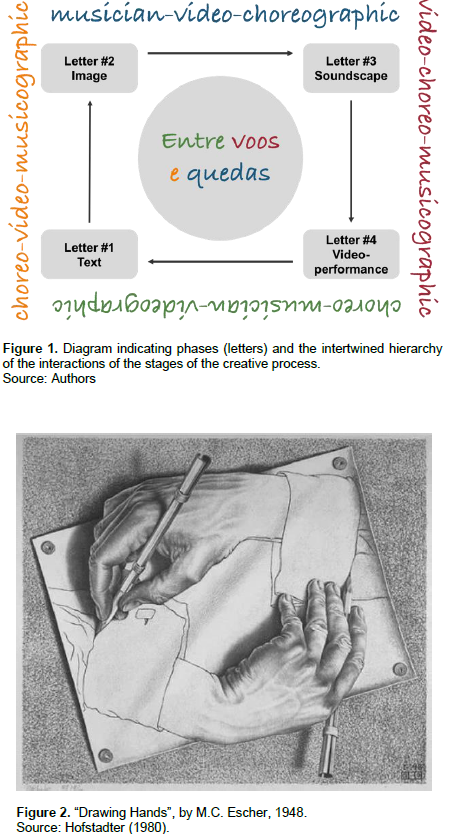

Entre voos e quedas is a music-video-choreographic composition, choreo-music-video graphics, or any other combination of these three elements. There were several stages during the creative process that led to the revelation of meanings, as described in "Notes on the Creative Process". The stages are described as an exchange of four letters, and the present article is considered a letter – Letter #5, a reflexive letter written after the creative process.

The authors of Entre voos e quedas collaborated remotely, as other artists who faced the challenge of creating during the COVID-19 pandemic did. Despite all technical difficulties, an unusual possibility emerged - collaboration between artists who could not normally collaborate due to distance. This barrier can refer to geographical dimensions, such as a Brazilian artist creating with an Indian, Portuguese, or Japanese artist. It can also refer to distances imposed by the overburdened daily life that contemporary times impose on all of us.

In this creation, the dialogue between the dancer, the composer, and the aerialist is presented from a creative perspective and a reflective point of view. It enters the field of multimodality, assuming the inseparability of artistic languages and the importance of investigating the synergetic development of a creative process. Outside the academic context and in the relations between music and dance, there are choreographies created for existing compositions or compositions created for a given choreography. It is arduous to transcend this logic when choreography is understood merely as a composition of movements and sequences. Since the advent of modern dance and especially in the context of postmodern dance, dance is no longer seen as just movement and analysis. In this sense, Entre voos e quedas seeks to transcend the dualism of "music for dance" or "dance for music" with a creative process in which authors and performers amalgamate, even from a distance. The action presented in a video graphics dialogue by the dancer and the aerialist is opposed to "environmental affordances" presented in a soundscape. Sound is not a purely rhythmic or harmonic entity, but an environment of dispositional states for the performers' actions.

This article begins by discussing aspects of Gibson's theory of perception, and then it reports in detail the creative process and its stages, organized by letters. Finally, the discussion reflects on the whole process considering the theory of perception-action and the concept of affordances.

Gibson’s ecological perception

The interaction between perception and action discussed by the American psychologist James Gibson in a set of seminal articles (Gibson, 1950, 1951, 1959, 1961) has been widely studied in several areas of knowledge. The ecological view of perception that Gibson addressed, at first, with visual perception (Gibson, 1966, 1983, 2015) dialogues with the concept of perception and action in the cognitive sciences (Vera and Simon, 1993), also in robotics (Chemero and Turvey, 2007), and with the musical affordances definition (Windsor and Bézenac, 2012).

Gibson's ecological perception (1966) posits that a person's perception of the environment is determined by its "affordances": the properties of the environment that indicate possibilities for action are perceived directly and immediately. In “The Senses Considered as Perceptual Systems” (1966), Gibson considered that perception is direct, not mediated by sensations. He rejected the point of view of perception as a passive process. Instead, he proposed that animals could actively seek information through exploratory actions and movements. Gibson also developed his concept of "invariants" explaining how their detection contributes to the perception and learning of the organism within its environment. For an animal, what gives meaning to the information available in the circumstance is its ability to act on the area and the surrounding possibilities (or affordances) to stimulate action. For Gibson, the meaning is precisely the coupling between these two factors: the affordances of the environment and the actions taken by the animal in the ecological niche where it lives. The meaning is in the interaction, not the object or the animal.

Another relevant concept to design theories is the idea of invariants, which are the properties that are available in the environment. As a result of their characteristics, which appear at different times, they help the animal to detect and, more importantly, to learn.

The concept of affordance is connected to the notion that Gibson constructs about "sense" or "feeling" in “The Senses Considered as Perceptual Systems” (Gibson, 1968). Considering the senses as perceptual systems is to say that the action of feeling is identical to perceiving. Perception cannot be distinguished from sensations derived from the act of interacting with the external world through the senses. The environment, then, plays a central role in the perceptual process. According to Gibson, the senses perceive when they operate as systems for detecting the external world immediately, "obtaining information about objects in the world without the intervention of an intellectual process" (Gibson, 1966). It emerges from the interaction between a subject endowed with "receptors" and "sensitive organs" connected to an external world capable of offering them stimuli. These stimuli are not simply a collection of sensations, as if the body were a machine of feedback variations. More than that: Gibson argues that environmental invariants are information about the perception of materials. These are recognized by the perceptive system. The affordances are where it is necessary to name the exploratory possibilities that an environment, from its invariant properties, makes available to the body that perceives them.

METHODOLOGY

The Dance Department of the University of Campinas works with methodologies for dance creation that have been developed in this space since its foundation in 1985 and the elaboration of the Bachelor’s in Dance pedagogical project (Andrade, 1987). By starting with the creative process, we try to invert the logic that theory must precede practice. In this sense, the conceptualizations come last.

“My process of developing performers' corporal conscience, coupled with mental evocations of images and sensations, aims to break down the boundaries between mind and body. Through this process, we try to establish a synchronic relation between dance movements and subconscious images of the dancer. This relation may refer to any kind of perception, idea, kinesthetic sensation, or present or evoked subjective state. At dance execution, both processes must happen simultaneously: this is a process of “imagining moving the body”, a truly “thinking doing” (Andrade, 2002, free translation)”.

Nowadays, there are many approaches based on practice as research. Chapman and Sawchuk (2012) list many names used by universities and councils in different countries for it, such as research-creation, arts-based research, and practice-led research. According to the authors, this methodology occurs in a wide range of fields, including social sciences and the arts, as well as in dance research.

“In this formulation, the conjunction research-creation no longer simply acts as an adjective, but as a noun, reifying not just the outcome (as focusing on “the project” tends to do), but on the combined process and product, the holistic totality that is the initiative, the inspiration, the trials and tribulations, successes and failures, and in some (not all) cases, material and intellectual outcomes that are mobilized through diverse means (Chapman, 2020)”.

Thus, in the case of Entre voos e quedas, we first created the video performance and, later, developed reflection and analysis on the creation process. In this sense, Gibson's approach is analogous. As such, Entre voos e quedas provides a connection between perception and action that can ground a subsequent reflection. This "inverted" the casualty of the investigative mode, that is, what we call artistic research is what will be described in the next topic.

Notes on the creative process

The composition of Entre voos e quedas was done in four phases: a text letter, an image letter, a soundscape letter, and a video-performance. As suggested earlier, it could be described as a choreo-musician-video graphics composition, among other combinations, given the intertwined nature of the hierarchy of the stages of the process.

In the diagram, only the four main letters of the creative process are shown. Observe how entanglement occurs when looking at the people who compose the letters: each person involved is interacting with the others via "letters", which replace traditional methods of everyone meeting in the same rehearsal room to discuss the process at the outset. If Letter #1 is the one sent by the dancer to her students, there was a previous letter (unnumbered) sent by the composer to the dancer. The video-response of the aerialist was sent directly to the composer, who does not know her. He responded by composing a soundscape that established a dialogue between the dancer and the aerialist. It is a dialogue that had already started in the video editing process.

The concept of intertwined hierarchy was used by Goswami (2000) when discussing the phenomenon of creativity. The author explains:

In a simple hierarchy, the lower level feeds the upper level, and this does not react in the same way. In simple feedback, the top level reacts, but you still cannot know what is what. In the intertwined hierarchies, the two levels are so mixed that we cannot identify the different logical levels (Goswami, 2000).

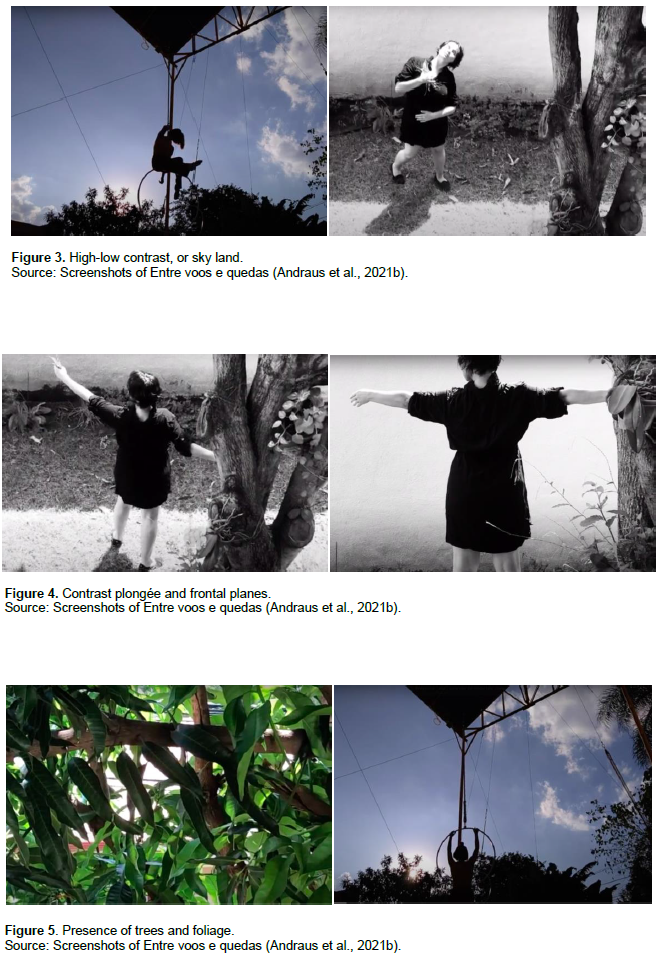

One of the examples used is the painting “Drawing Hands” by Escher (Figure 2). To explain Hofstadter's (1980) concept of intertwined hierarchy, Goswami analyzes the painting “Drawing Hands”:

The left hand; in this case, is drawing the right hand, and the right is drawing the left, one drawing the other. This is self-creation or autopoiesis. It is also an intertwined hierarchy. And how is the system creating itself? This particular illusion is created only if we remain within the system. From the outside, from where we see it, we can see that the artist, Escher, drew both hands from the inviolate level (Goswami, 2000).

It should be noted that the inviolate level is well-defined when referring to arts that are "delivered". That means, once ready and publicized, the artist no longer changes them. In performing arts, this inviolate level is more intangible since each performance is a unique event. Artwork can be modified according to the context in which it will be presented or even according to feedback received by the artist. In the case of Entre voos e quedas, what enables the authors to carry out such analysis is the fact that it is developed with video as support and as a component of its language. Since there is no intention to reissue the work a posteriori, the level of inviolate status exists. However, throughout its creation, the stages were mutually affected by letters that not everyone could see simultaneously. The four main cards are discussed in the following.

Letter #1: Text

The whole process began when the composer sent a letter to the dancer. The intention was to compose sequences with another choreographer. However, this intention did not materialize. The dancer, then, in a similar process, sent a letter to students under her guidance, and from these, she received responses. These served as raw materials for developing a set of videos. Later, the videos were launched in a specific channel of the research group under her coordination at Unicamp (Andraus, 2021).

Letter #2: Image

The letter from the dancer was sent to dance students under her guidance on January 12th, 2021, with the following content freely translated into English from Portuguese:

Hello! How long have we not spoken? Not so much, isn't it? We always talk to each other, after all:-)

I am happy with the dialogue we have established for developing your research and consolidating a more collective production pertinent to the intercultural perspective in the performing arts.

I was curious about everything you did and do, everything you lived and still live at the University of Campinas... What makes you want to study inter-culturality? If you could choose an aspect, a sound, a tone, a cadence of movements that would express the most essential in this encounter with the other, with the different culture, with otherness... What would that be?

I will ask you for a favor that may seem unusual: that you do not answer this letter with another letter but with a small sequence of movements made by you in your home, using a flower, an apple, or a book. Use your cell phone. Don't worry about editing or image resolution... Just use your mobile lying down in a landscape (horizontal) position.

Choose a special outfit for your body. Choose one or more locations in your home. Choose whether to have other people in the video or not. If you want, you can send more than one answer.

The object may be with you on your hands, your body, or elsewhere. It can change places, and you can move. The cell phone can move. Table, floor, handrail. Think of your cell phone as an observer who can see you from the front, below, above, and from all sides.

Your sequence can be the repetition of the same movement or a chain of movements. It may be a short body-narrated story, or it may not.

Feel free to respond or not to my letter. If you are going to answer, I ask you to do it by 2/12. If you prefer to accept and not manifest soon, everything is fine too. We are in no hurry ... :-)

Among the video-letters received, two were materials used to create the video “Books, Flowers and the Pestilence” in partnership with artists from Pondicherry University (India), and two were solo video-letters. One of them was created by a student who, in addition to being a dancer, is a circus artist/aerialist. It did not form a nexus of symbolic significance with any of the others. This aerialist or dancer chose an apple as an object and developed her sequence on the aerial hoop, a circus aerial apparatus. At the same time, it was not a solo performance. In this instance, the dancer decided to make a video-letter of herself dancing. Then, she composed the response video letter in a collective creation involving herself, the aerialist, and the music composer.

So, in the case of Entre voos e quedas, the dancer had previously seen the trigger video and created her own. This was done intending to create a symbolic dialogue with the first piece. At that moment, from the perspectives of the senses and meanings, there were no clearly articulated intentions, only intuitive ideas of the technical-choreographic aspects of the composition of symbols, such as high-low, sky-earth, and circle-plane. Among the definitions that emerged in this phase, it can be cited:

(1) The wish to establish a counterpoint with the aerial characteristic of the chosen technique (affordance), developing, in contrast, a sequence with plongée framing (from top to bottom) of another sequence starting with the body completely adhered to the ground (Figure 1);

(2) Filming of the same sequence in the frontal plane for editing work (Figure 2);

(3) The presence of trees and foliage creates a similarity with the first video (Figure 3);

(4) The use of a black-and-white filter (that is, noir) to contrast with the colorful first video (Figure 1).

For editing, the video filmed in a plongée frame (video 2) was first decoupaged, then the same was done with a video filmed in the frontal plane (video 3) (Figure 4). These videos have similar sequences, repeated in two records, and due to the fact that improvisational procedures are similar but not identical. A succession with these materials that made sense was created in terms of the narrative and from the point of view of the composition of the movements. Then the aerial hoop video (video 1) was decoupaged, which entered the sequence, and the process of meaning construction began.

The triggers and initial choices were determined by some technical criteria: the creation process in dance focused on creating movements with predetermined objects and choreography in one place to combine with the choreography in another. From a generic compositional point of view, the dancer played with "high and low" and "heaven and earth". The meanings begin to emerge by themselves during the editing/composition process of the pre-final version of the video, not yet definitive, prepared for sending to the composer.

Note that, in a collaborative creation process, it is assumed that the co-authors have an opinion on all materials. It is not contradictory that the composer influences dance creation or the choreographer influences music conception. There are no specialties. Artistic languages serve as bases and facilitators of concepts and expressions of communication between artists. The languages themselves are affordances.

When editing the videos, senses and meanings began to emerge and transformed the composer's perception of the material so far. These senses related to themes such as death, example is expressed both by the black color of the clothes and by the noir filter. In addition, an older ballerina and a young ballerina are present at work – a contrast that was not previously planned. The "life-death" theme joined with the sense of balance implied in this duality, and it is reinforced by the cyclical structure of the edition: the excerpts are ordered in an almost algorithmic way, in a kind of “rondo” (Cole, 2001), one of the most organic structures in composition. In addition, the composer realized the risk implicit in the poetic theme -both the aerial hoop and the tall tree are at risk of falling (Figure 5).

The sense of falling and risk emerged from the improvisational process of editing the videos. In minute 4:47, this becomes more obvious as the apple falls from the head of the dancer from the top of the aerial hoop, followed by the action of the other dancer to pick up leaves from the ground impetuously – which she had been developing since minute 3:30. The emphasis here is on the intuitive approach to composing: a more rational approach would lead to only beginning the picking of leaves (from video 2) after an apple has fallen (from video 1), and all of the work of introducing the flow of ideas would be lost.

It can be interesting for spectators when an artwork unexpectedly moves their minds. An overly intelligible artwork can break the barrier between art and communication, reducing its potential to induce imagination, nurture affection, and appease anguish – it just communicates. How to put a topic as distressing as death on the agenda in a light way other than by art?

The fall of the apple in minute 4:47 connects, also, with

the first scene of the dancer from video 2 lying on the ground in the second 0:11. It looks like a bird fallen under a tree, a bird that hums along with the entire video, a bird that never dies. However, the dancer on the floor is a blackbird. A crow perhaps – an omen of death. It is said, in ancestral wisdom, that crows reach the battlefield even before the battle begins because they sense that a fight is going to take place there. The raven’s death at the beginning of the video is a way of killing death itself. It is a metaphor for the lightness that the times of COVID-19 are demanding of us.

Letter #3: Soundscape

Here explains the (dis)coupling and movement and the relation with the insertion of instrumental sounds. The first is fundamental for establishing the relationship between environmental affordances produced by the dancer's movements. After the video editing, the composer received a version without music (Letter #2).

Then, he developed a final creative approach concerning the interaction with sound, environment, and musical instruments.

The composer initially created a piano improvisation followed by a score for a music ensemble for soprano, vibraphone, alto flute, and electric guitar. The composer also compiled environmental sounds for composing the foley of the video-performance. The foley insertions were composed of wind and rain sounds, birdsong, body-dragging noises on the ground, and the sounds of dry leaves. It is noteworthy that some of these elements were present in the original recordings, others not. The coupling between the videos from the two separated environments was sought, sometimes in a diegetic way, other times in a non-diegetic way (Chion, 2008).

Finally, the melodic profiles of the musical instruments were mixed with the foley. These last elements do not characterize the scenes but extrapolate their meaning, as does the distorted guitar sound in counterpoint to the choreographic scene at the end of the work. All these elements were assembled into a sound texture which, due to its intertwining, is called soundscape (Letter #3). While composing the soundscape, the composer sent the dancer a letter-poem, asking the dancer and the aerialist to record a narration:

Letter to flying and falling:

our body on the floor

weighs no more than

the force that lifts it.

not even the face in the sky

suffers more than

the longing that invades her.

not even the skin in the desert

heats up more than

the breath that runs through it.

nor does the gesture in the wind

escape more than

the trail that draws it.

these windows, enchanted

by sacred lines and doors,

take us from here to places

we do not know how to own.

in these (over)flights

of care (lessness) birds

our mind finds

the body in free fall.

For the dancer, it was clear that the narration would come to compose the soundscape. Neither the image nor the soundscape letters were known to the aerialist when the narration was recorded.

After that, the composer discussed his impressions of the edited video with the dancer. During a conversation, the dancer avoided sharing the meanings she had already evoked from her experience with the material to interfere with the musical composition process as little as possible. That conversation revealed that the meanings were coincidental. While the dancer spoke, the composer freely noted:

I will describe my direct perception. Ecological affordance is present in the movement of the wind and the motion of the bird. Then there is the choreography, composed of free moves with varying degrees of freedom. They appear to me to be neither sequential nor narrative, but as if they were a body trying to adapt to the environment, a body that is ecology itself and an environment that may be a body (transcript of the conversation; talk of the dancer, free translation).

In the sequence, the composer cited the musical references to which the video referred especially Satie et al. (1996) and Schafer (1977). The dancer asked if he already had an idea of the climate, and the composer said yes. From the composer's perspective, the dancers' movements dialogue with Satie's music from the point of view of economy or minimalism in their mutual conversation. In this way, he also connected the notion of "furniture music" (Satie et al., 1996) to background and ambient music development. In addition, it would be interesting to link the soundtrack to the notion of soundscape by Canadian composer Murray Schaffer. These two points were connected to the creation of Letter #3, which is the soundscape. The composer mentioned some sound textures that he would use. Also, he informed the dancer that the instrument would be the piano, which was the instrument also imagined by her. These coincidences, far from being explained by metaphysical theories, find their foundation in Gibson's theory of perception. Gestalt theory also explains these coincidences:

“Gestalt is a German word nowadays adopted worldwide, as there is no equivalent in other languages. Gestalten means "to give shape, to give a significant structure" [...]. Our ordinary dictionaries only recorded so far the first sense that is the historical one, of Gestalt psychology. This theory says our perceptual field is spontaneously organized in the form of strong and fully structured and meaningful sets ("good ways" or gestalts). The perception of totality – for example, a human face – cannot be reduced to the sum of the stimuli perceived since the whole is different from the sum of its parts – thus, water is different from oxygen and hydrogen! In the same way, one part in a whole is something quite different from the same part isolated or included in another whole because it extracts particular properties from its place and function in each of them: thus, in a game, a shout is different from a shout in a deserted street, being naked under the shower does not have the same meaning as walking naked on the street (Ginger, 1995, free translation)”.

Finally, a multimodal video-performance emerged with the integration of video and this soundscape, converging toward Letter #4.

Letter #4: Entre voos e quedas

Letter #4 is the video-performance itself. As written in previous work:

In editing the videos, meanings started to emerge and transform the perceptions of the creators about the material produced so far. Finally, the (un)coupling of the soundscape with the videos generated new relationships between environmental affordances, musical instrument commentary, and foley noise. The composer also sent a poem-letter to the dancer and the aerialist. He asked both artists to record the reading of the text. In this way, a catalytic element emerged and gave birth to the notion of (over) flight of care (less) birds. Then the different components of the piece came to their final version [the video-performance] (Andraus et al., 2021a, free translation).

Letter #4 was presented at the 15th International Symposium on Cognition and Musical Arts (SIMCAM) on 26/05/2021 (Andraus et al., 2021b).

Letter #5: This article

Dear reader, this article is also a letter: Letter #5. To understand it better, before proceeding with the reading, it is suggested that you watch Letter #4 on YouTube (Andraus et al., 2021b).

DISCUSSION

The article discusses an interdisciplinary approach, from the point of view of the interface, between the languages of dance, circus, music, and video within artistic research co-worked by a dancer, an aerialist, and a composer. However, in each of these fields, artists also act in an interdisciplinary way. This can also be explained by the affordances theory, as discussed in Gibson's ecological perception approach.

From the point of view of choreology (Preston-Dunlop, 1987), dance is understood and analyzed from its multiple references. It ranges from visual elements, which can include the dancer and his appearance (Is it a woman? Is it a younger or older person? How many dancers are there?) and the aural elements (is there sound, music, reading a poem? How does silence oppose sound?). Naturally, it can go through movement and its characteristics, studied in the field of Eukinetics (Laban, 1978; Rengel, 2001).

The formation of the dancer (especially in the contemporary context) permeates a sum of experiences composed in an eclectic perspective: dancers can start their journeys in classical or contemporary dance and move through different experiences throughout their life careers. It ends up adding patterns of movement and/or composition. These are manifested in their improvisational works as affordances, through compositional strategies that can take place in an eclectic way, by fusion or as a revue, names adopted by Monten:

“What is of greatest interest for the purposes here, are the ways that choreographers have found to incorporate so many different dance languages into their own. I identify three basic strategies. One I will call the revue: stringing together a series of discrete, contrasting dance episodes – often with a short pause for applause and costume changes – such as one might have seen in the Ziegfeld Follies or in an evening of works performed by Diaghilev?s Ballets Russes. A second form of combining ingredients I term fusion: blending disparate dance elements together so thoroughly that they appear to fuse together into a new, hybrid dance form. [...] A third strategy for combining ingredients – and the focus of my essay – I call eclecticism. [...] [it would be like a] compote – a mixture of ingredients, with each maintaining some measure of its original color, texture, and flavor (Monten, 2008).

The presence of two of these three compositional strategies in Entre voos e quedas can be seen: revue and fusion. Both were applied to the material from the circus and contemporary dance. The revue was applied to the video montage and the fusion to the movement research: in video 1, the languages of dance and circus, and in video 2, dance and Chinese martial arts. For example, in the minutes 1:57 to 2:00, approximately, this affordance is evident – it is a solo and abstract sequence of blocking reactions to attacks. In the edition, the dramaturgy of action is present in one of the sequences (falling, getting up, picking leaves, letting them fall), interspersed by another (approaching, climbing on, dancing on the hoop).

CONCLUSION

In this article, it was demonstrated that meanings and senses emerged throughout the creative process. This result came from an awareness of what were the symbols brought by the montage of the creative process. The themes of death, pandemic, or the fall of a bird were not initially addressed until they experienced the artistic process's emergence. As in Gibson's thought, meaning is constructed from affordances developed during creation. In the soundscape composition, the collage process interlaced the composer's voice at the piano, the comments of musical instruments and the foley elements.

As initially considered, the meanings of artistic creation are unveiled by the composition, even though an ordering of stages (including from the point of view of signification) has occurred in its compositional process.

In synthesis, the circularity of the stages produced a gathering of connotations. The meaning of the work is more than the sum of the individual senses of each of the environments and each stage of the process. It is transcendent and unfinished: it defines itself in each enjoyment experience, with the final user having a fundamental role in this process. The work is its proper affordance.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the University of Campinas, the São Paulo State Research Foundation (FAPESP) for the master's fellowship granted to the third author/aerialist (process n. 2018/25696-1), to the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES), for the granting of resources to the project "Poetics of sound and body in the interdisciplinary dialogue between art and technology: the study of creation research in Digital Humanities", linked to the institutional project of the University of Campinas in CAPES-PrInt and the Universal CNPq project, “Poe?ticas do Som e Movimento: estudo de performances multimodais com suporte tecnolo?gico”. 429620/2018-7. The composer is supported by the CNPq PQ project “Criac?a?o e Ana?lise Musicais com aporte de Processos Cognitivos, Interativos e Multimodais”, 304431/20184.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests

REFERENCES

|

Andrade M (1987). Projeto de Criac?a?o do Departamento de Artes Corporais Of. No 062/85 - IA a? Reitoria da Unicamp. |

|

|

Andrade M (2002). Reflexo?es acerca da pesquisa artística em danc?a. Anais do II Congresso Brasileiro de Pesquisa e Pós-Graduação em Artes Cênicas. Available at: |

|

|

Andraus MBM (2021). Estudos Interculturais em Artes Presenciais. Available at: |

|

|

Andraus MBM, Manzolli J, Santos MP (2021a). Entre voos e quedas: (sobre)voos de pássaros (des)cuidados. Caderno de Resumos do XV Simpósio Internacional de Cognição de Artes Musicais 2021:66-69. |

|

|

Andraus MBM, Manzolli J, Santos MP (2021b). Entre voos e quedas [video file]. Available at: |

|

|

Chapman O (2020). Foreword. In Loveless N. Knowings and knots: methodologies and ecologies in research-creation Edmonton: The University of Alberta Press. |

|

|

Chapman O, Sawchuk K (2012). Research-Creation: Intervention, Analysis and "Family Resemblances". Canadian Journal of Communication 37(1):5-26. |

|

|

Chemero A, Turvey MT (2007). Gibsonian affordances for roboticists. Adaptive Behavior 15(4):473-480. |

|

|

Chion M (2008). A Audiovisão: som e imagem no cinema. Lisboa: Edições Texto & Grafia. |

|

|

Gibson JJ (1950). The Perception Of The Visual World. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. |

|

|

Gibson JJ (1951). Theories of perception. In Dennis W, Leeper R (eds.), Current trends in psychological theory. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. pp. 85-110. |

|

|

Gibson JJ (1959). Perception as a function of stimulation. In Koch S (ed.). Psychology: A study of a science. New York: McGrawHill. pp. 456-501. |

|

|

Gibson JJ (1961). Ecological optics. Vision Research 1:253-62. |

|

|

Gibson JJ (1966). The Senses Considered as Perceptual Systems. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. |

|

|

Gibson JJ (1983). The Senses Considered as Perceptual Systems. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press. |

|

|

Gibson JJ (2015). The ecological approach to visual perception. New York, London: Psychology Press. |

|

|

Ginger S (1995). Gestalt: uma terapia de contato. Rangel SS, translator. São Paulo: Summus. |

|

|

Goswami A (2000). O universo autoconsciente: como a consciência cria o mundo material. 3rd ed. Rio de Janeiro: Rosa dos Tempos. |

|

|

Hofstadter D (1980). Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid. New York: Basic Books Hooughton-Mifflin. |

|

|

Laban R (1978). Domi?nio do Movimento. Ullmann L. (Org.). Vecchi, AMB, Netto MSM, translators. 3rd ed. Sa?o Paulo: Summus. |

|

|

Monten J (2008). Something old, something new, something borrowed...: eclecticism in postmodern dance. In: Bales M, Nettl-Fiol R (eds.). The body eclectic: evolving practices in dance training. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. |

|

|

Preston-Dunlop V (1987). Dance is a language, isn't it? 3rd ed. London: Laban Centre for Movement and Dance. |

|

|

Rengel LP (2001). Diciona?rio Laban. [Master thesis]. Campinas: Instituto de Artes, Universidade Estadual de Campinas. |

|

|

Satie E, Volta O, Melville A (1996). A mammal's notebook: Collected writings of Erik Satie. London: Atlas Press |

|

|

Schafer RM (1977). The Tuning of the World. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart. |

|

|

Vera AH, Simon HA (1993). Situated Action: A Symbolic Interpretation. Cognitive Science 17(1):7-48. |

|

|

Windsor WL, De Bézenac C (2012). Music and affordances. Musicae Scientiae 16(1):102-120. |

|

Copyright © 2024 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article.

This article is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0