An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants was conducted in Abay Chomen District, Western Ethiopia from September 2014 to August 2015. This study documents indigenous medicinal plant utilization, management and the threats affecting them. Ethnobotanical data were collected using semi structured interviews, field observations, preference and direct matrix ranking with traditional medicine practitioners. The data were analyzed using descriptive statistics; informant consensus factor and fidelity level using MS-Excel 2010. The ethno-medicinal use of 93 plant species belonging to 85 genera and 52 families were documented in the study area. The highest family in terms of species number is Fabaceae. Herbs were dominant (31.3%) flora followed by shrubs (30.1%). Most of the medicinal species (52.7%) were collected from the wild. Most of the plants (60.2%) were reportedly used to treat human diseases. The most frequently used plant parts were leaves (34.68%), followed by roots (23.39%). Fresh plant parts were used mostly (53.3%) followed by dried (29.3%) and the remaining (17.4%) either in fresh or dried. Among the preparations, pounding was the dominant (34.1%) form followed by powdering (13.29%). The remedial administration was mostly oral (54.91%) followed by dermal (30.64%). The highest (88.89%) informant consensus factor was associated with Ocimum urticfoluim followed by Allium sativum (86.67%). The fidelity level of Allium sativum was calculated irrespective of malaria treatment. Direct matrix analysis showed that Carissa spinarum was the most important species followed by Syzygium guineense indicating high utility value of these species for the local community. The principal threatening factors reported were deforestation followed by agricultural expansion.

Characteristic features of the study area

Abay Chomen is one of the 180 district in the Oromia Region of Ethiopia. Today, this district is sub-divided into 31 Farmer Associations. Fincha’a is the capital town of the district, about 47 km from the zonal capital Shambu and 280 km from capital town of Oromia called Finfinne. The district has a latitude and longitude of 09°54′N 37°27′E with an altitude ranging from 880 to 2,400 m above sea level. The mean annual temperature and rainfall are 22 to 27°C and 510 to 1530 mm, respectively. The National Census (2007) reported a total population of the district, 48,316, of whom 24,972 were men and 23,344 were women. A survey of the land in this district shows that 11.4% is arable or cultivable, 2.2% pasture, 1.4% forest, and the remaining 83.8% is considered mountainous and part of the Fincha'a Sugar Project. Niger seed, teff, maize, wheat, barley, bean, and root and tuber crops such as potato, ''Anchote'' and others are dominant crops grown in the area.

Reconnaissance survey and study site selection

A reconnaissance survey was conducted from September 2, 2014 to September 4, 2014. Before starting the ethnobotanical study, contacts were made with various offices (District administration, tourism and culture, agriculture and rural development, traditional healers’ association and health affairs) to seek permission to carry out the study by informing them about the aims and significance of the study. In this way, full legal procedures were followed and the informed consent of interested participants was obtained. Six rural villages, namely, Fincha Sukuar Project, Sementegna Camp areas, Achane, Kolobo, Gengi Ketela, and Jare were selected for the study. Relative distance, community-forest interactions and altitudinal differences were the basic site selection criteria. Relative distance and community forest interaction were taken as criteria after collecting information from Kebele administrative offices and inhabitants of the area during the reconnaissance survey in order to compare the indigenous knowledge of the communities found nearest to the forest with those found relatively far away (reached after traveling for more than 30 km).

Informant selection

A total of 90 informants (70 males and 20 females) between the age of 18 and 80 were interviewed in this research. Purposive and random sampling techniques were employed to select traditional herbalists and general informants, respectively. The Traditional Association leaders, members of the tourism and culture office, elderly people and religious leaders helped to identify the key informants. In addition, the identified traditional practitioners and members who had earlier been treated by the healers also helped to identify other traditional experts. The general informants were randomly picked (from the list of inhabitants) during field and house visits (15 in each study site) by checking their names from the list of residents obtained from Kebele offices. All interviews were administered after obtaining voluntary consent of each informant and assuring them that the data will be used only for academic purposes.

Data collection

Ethnobotanical data collection was accomplished from September 2014 to August 2015 by living in close contact with the community in the study area, following standard methods (Martin, 1995; Cotton, 1996; Cunningham, 2001). Accordingly, semi-structured interviews, guided field walks, direct observations, market surveys and focus group discussions with key informants and other knowledgeable community members were applied and their knowledge on medicinal plants gathered. Interviews were held based on checklist of questions prepared beforehand in English language and simultaneously translated into Afan Oromo. Interviews focused to informant’s demographic features including sex, age, marital status, occupation, religion, educational background, and duration of time an informant lived in the study area, and indigenous ecological knowledge (traditional ways of classifying vegetation, plants, landscapes and the soils in the area). The major part of the interviews were focused on the local names of medicinal plants used, their habits and habitats, plant part/s used, remedy preparation methods, materials used during preparation, condition of preparation, additives/ingredients used during preparation and administration, dosages administered, and route of administration. Likewise, side effects of the medicine (if any), use of antidotes for adverse effects, the season, month, dates and time of collection and preparation of plant medicines, and market value were also included. Further, the distribution (status) of medicinal plants, the interaction of healers with the district administration, threats and major problems, conservation methods, source of knowledge and ways of transfer and number of years of service as traditional healer were also the major interview points targeted, following the methods used by previous investigators (Martin, 1995; Balick and Cox, 1996; Cotton, 1996).

The semi-structured interviews held with informants usually started at their sitting places and further broadened into field walk with interviewed informants in order to see the plants mentioned in their habitats and voucher collections following Martin (1995). This activity further helped to record growth habits of medicinal plants. Focus group discussions were done with traditional medicinal plant association members, other herbalists, monks and general informants to obtain additional information and to check the reliability. Informants were contacted two to three times and responses of an informant in harmony with each other were taken as relevant and used for data analysis. At times, the preparation methods of the medicinal plants were said to be secret and were not included during discussion. Most field observations were conducted with a single informant in order to keep the knowledge top-secret as this was what the healers in particular preferred. Some of the traditional healers were genuine herbalists, well-known by the local community and owned traditional home pharmacies derived from plant remedies. They were asked to demonstrate their work at their homes and in the field, which was recorded in order to check the consistency in knowledge and practice on the preparation of remedies and their effectiveness. The patients encountered at healers’ homes were also asked about the traditional plant medicines they have used and their effectiveness when applied by healers.

Plant collection and identification

Voucher specimens were collected for each plant species during guided field walk with the informants. At times, the field activities included taking notes on plants and the associated indigenous knowledge with preliminary identification of the plants to family and sometimes to species levels. Photographic records were also taken in the field to capture the field sites, plants and other useful memories. The specimens were dried, deep-frozen, and determinations were made at the Ethiopian National Herbarium (ETH), Addis Ababa University, using taxonomic keys and descriptions given in the relevant volumes of the Flora of Ethiopia and Eritrea (Edwards et al., 1995; 1997; 2000; Hedberg and Edwards, 1989; 1995; Hedberg et al., 2003, 2004, 2006, 2009) and by visual comparison with authenticated herbarium specimens. Finally, the accuracy of identifications was confirmed by a senior plant taxonomist and the voucher specimens with labels were deposited at the ETH.

Data analysis

The ethnobotanical data were analyzed using Microsoft Office Excel spreadsheet (2010). The Excel ® was used to calculate sum, percentages, tabulate and draw graphs. Ethnobotanical ranking and scoring methods such as preference and direct matrix rankings as well as pair-wise comparisons and informant consensuses were employed to distinguish priority species and to check consistency. Preference/priority ranking activities were employed on five most preferred and widely used medicinal plant species for the treatment of diarrhea and the most threatened medicinal plants. Direct matrix ranking was employed for the seven most utilized multi-purpose plant species and for the eight factors considered most threatening to medicinal plants. Pair-wise comparison was made on five of the most preferred and commonly used medicinal plants against gonorrhoea. To do this, the number of possible pairs was determined by applying the formula n(n-1)/2, where n is the number of medicinal plant species being compared. For all the aforementioned ethnobotanical ranking and scoring techniques, the same ten key informants who had long time practical experience in traditional plant medicine preparation, administration and collection were engaged. The strength of knowledge of the key informants was evident to the first author who witnessed the clarity of explanations and accuracy of actions. The overall procedures for these activities were conducted following standard ethnobotany texts (Martin, 1995; Balick and Cox, 1996; Cotton, 1996). Informant consensus factor (ICF) for different ailment categories was calculated to test agreements of the informants on medicinal plant knowledge of each category by using the formula ICF = NurNu/Nur-1, where nur is the number of uses reported in each category and Nu is the number of species reported in each category (Heinrich, 2000).

Ethical consideration

All data collections were done with special care on the base of the cultural view of the local communities in the study area. Informants were also informed that the objectives of the research were not for commercial purposes but for academic reasons. Since, ethno-medicinal indigenous knowledge is only obtained from traditional specialists within the community so any value that will obtain as a result of the research will benefit the community. According to ethno-biology code of ethics indigenous knowledge should be protected and a part of the value generated should be transferred back to the authors of the knowledge. Finally, informants accepted the idea and came to reached an agreement.

Indigenous knowledge on health concept

In the study area, the local people call health (“Fayya" in Afan Oromo) which is taken as a special wealth provided by God ("Waaqayyo"). They believe or understand as ailments are the cause for health upset caused either with organisms (“ilbiisa”) or can be sent from God as punishment (“Dheekkamsa Waaqayyoo”) for wrong doings. They can also classify health problems, as those that can be treated and that cannot. For instance, the informants pointed that AIDs “dhibee baraa” and spiritual diseases “dhibee ayyanaa” are non-curable either traditionally or by modern treatment. From discussion made with elders several poems, proverbs and songs were recorded reflecting the values of health to the local people. To cite few of these: “Fayyan muka nyaata” meaning “healthy man does everything”. “Dhibbi abbaan

hin beekne fayyaa dha" meaning “a great wealth and gift is health”. "Fayya xaba seete qayyaan laga ceete” meaning “health needs special care”. These proverbs indicate that, health is considered as a great asset, which is assumed as a life engine for any aspects of life in the area.

Indigenous ecological knowledge of people in the study area

The inhabitants of the study area are owners of rich ethnobotanical and ethno-ecological knowledge as demonstrated by their wide array of knowledge on environmental matters. They classified the land forms, vegetation and soil based on knowledge surviving from ancestral practices, now evident through their elaborate emic categorization systems.

Use based land classification by indigenous people

In the present study, it was found that indigenous people classify their land based on use. (i) Lafa dheeddicha -meaning grazing land saved for cattle, calf, donkey, mule and horse for grazing, (ii) Lafa qonna, meaning agricultural land form that serves for cropping, (iii) Lafa bosonaa, meaning forestland secondary forestlands, where different plant species are found, which is the source of different wood and wood products, (iv) Gooda, refers to an extensive area that is not suitable for agriculture in most cases. It is left aside by the community for common grazing and browsing, (v) Lafa caffe, meaning marshland suitable for irrigation and grazing, (vi) Lafa manaa, meaning residential land where the community has settled, and (vi) Luugoo lagaa, meaning riverine banks where deep gorges or simple gorges are found and better vegetation exists along its course.

Topographic land classification by indigenous people

Indigenous people of the area classify their land also based on topographic landscape: (i) Gaara/Tullu, mountain area characterized with higher altitude and covered with vegetations, (ii) Tabba, land forms with smaller elevation (hills) compared to Tullu, on which agriculture, grazing and other practices can be performed, (iii) Goodaa, refers to an extensive field characterized with lower elevation area, left aside by the community for grazing and browsing. It is a plain around reverine areas, (iv) Dirree/Lafa ciisaa, plain on which settlement and agricultural activities are usually practiced, (v) Qilee/Bowwa, refers to gorges. This land form is mostly covered, shrubs and herbs, and rarely trees and climbers. It is used neither for agriculture nor for grazing, and (vi) Katta, refers to land forms that are dominated by different size of rocks. It is mostly used for grazing.

Soil classification by indigenous people

Indigenous people classify (name) soil based on color, texture and suitability for cropping. (1) Biyyoo diimillee, meaning clay soil, they call it biyyoo diimillee, because of its red color and poor fertility, (2) Biyyoo kootichaa, meaning black soil due to its color and with better fertility than other soil types, (3) Biyyoo cirrachaa, meaning sand soil sandy soils and silt soils resulting from deposition by erosion. This soil type is easily distinguished by its content of fine sand soil with silt, and is suitable to grow specific crop types, (4) Biyyoo walinii, meaning mixed soil type characterized by containing all the aforementioned three soil types, (5) Biyyoo Kosii, soil type containing high amount of organic materials drawn from household left wastes and animal excreta.

Vegetation classification by Indigenous people

According to some informants from the study area, vegetation of the study area is classified based on dominating tree species and density of plants that cover the land. (a) Bosona, this type of vegetation is with densely populated plant species and composed of a range of larger trees, where many wild animals dwell, (b) Luugoo lagaa, refers to riverine forest. The range of plant species composition here varies based on the accessibility of plants existing there to both humans and livestock. In areas where the riverine is shallow deep, it is more densely populated with different species, while in areas where human and livestock interference exists the composition is less, and (c) Ciccita (Hurufa), open woody and shrub land with patches of trees, bushes, shrubs and herbaceous species, and (d) Caffee, marshy vegetation in marshy fields suitable for grazing.

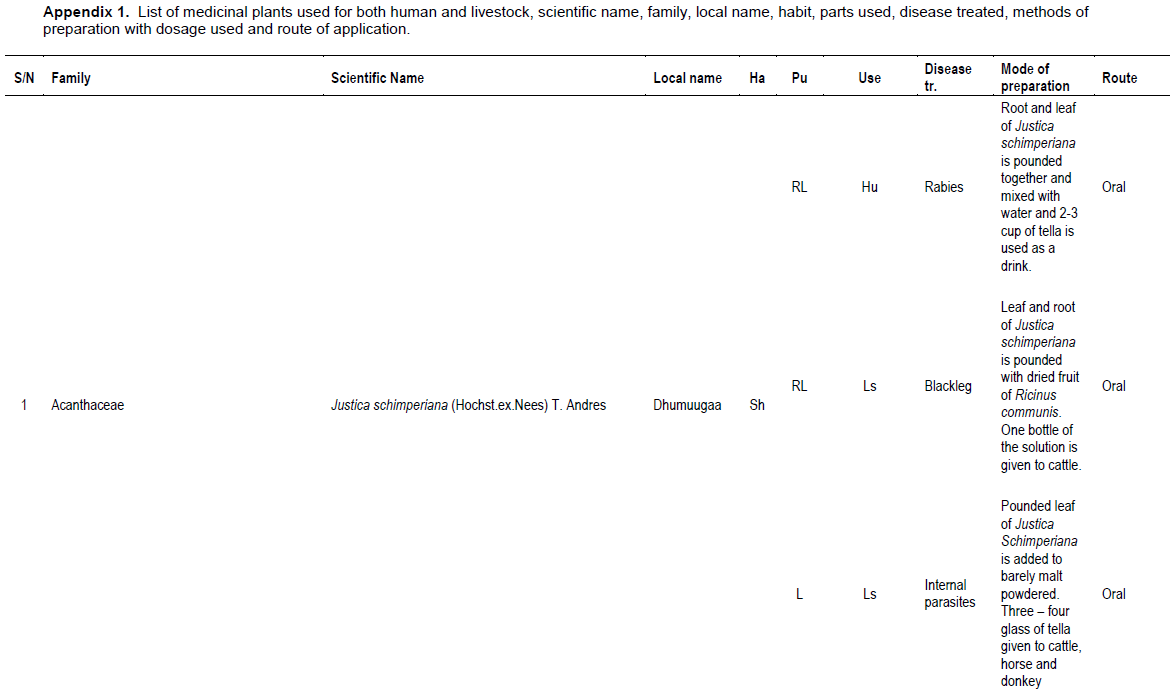

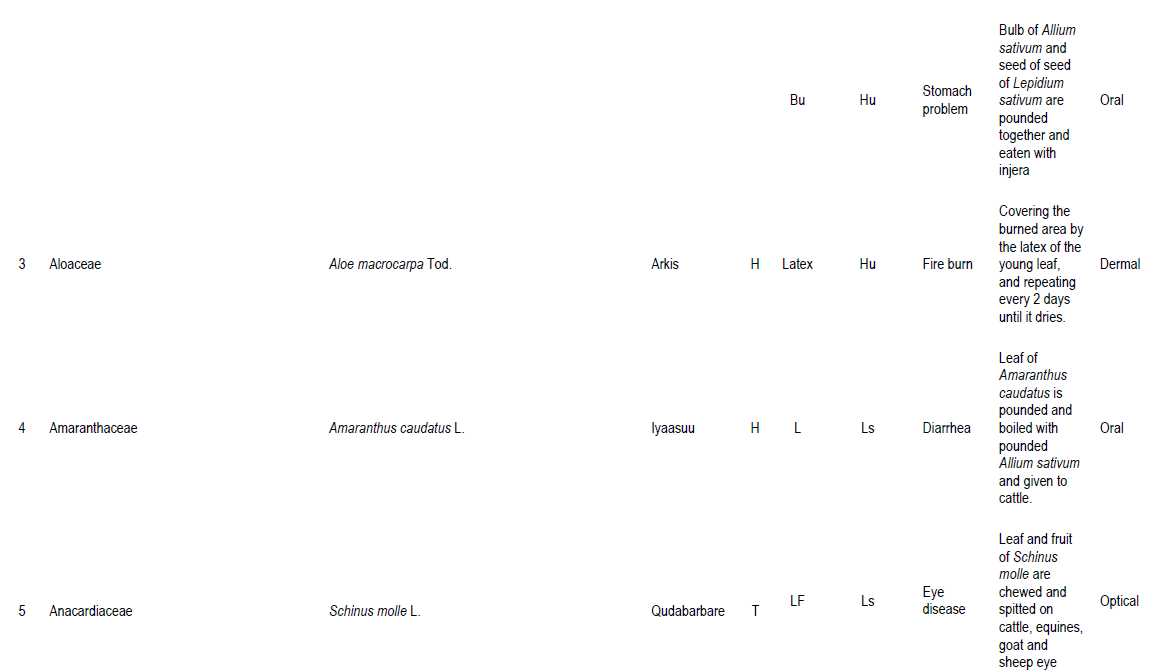

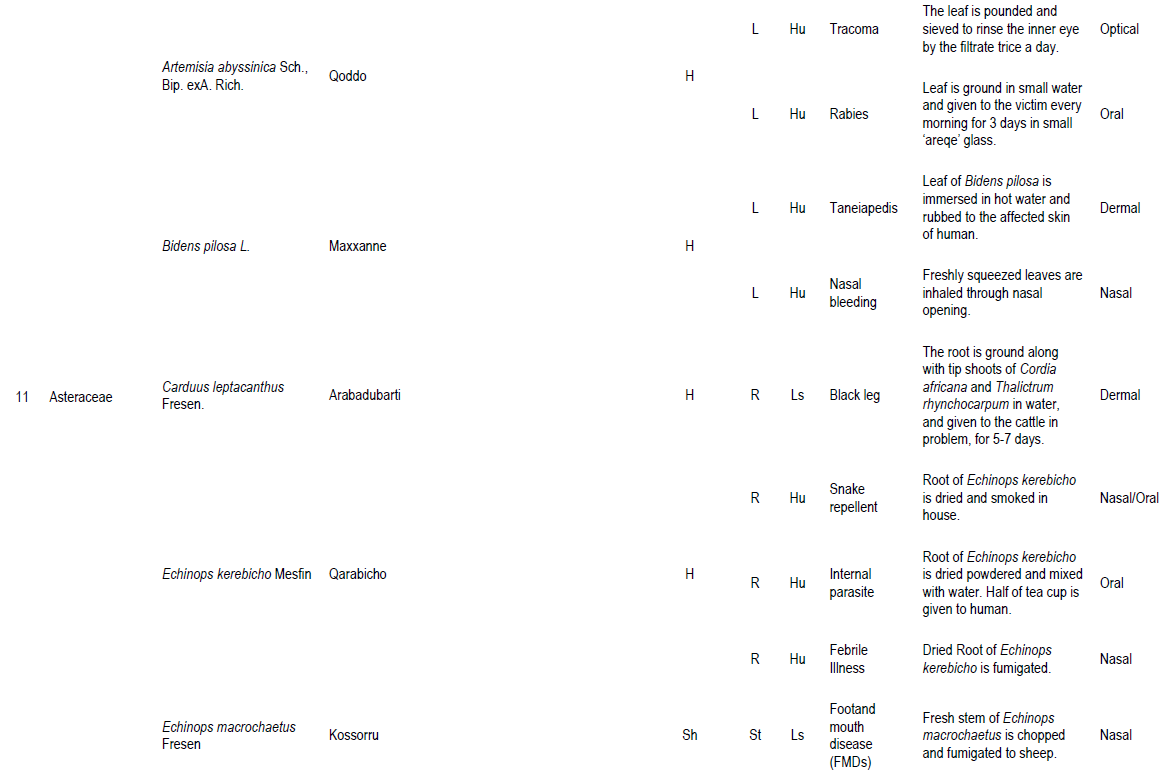

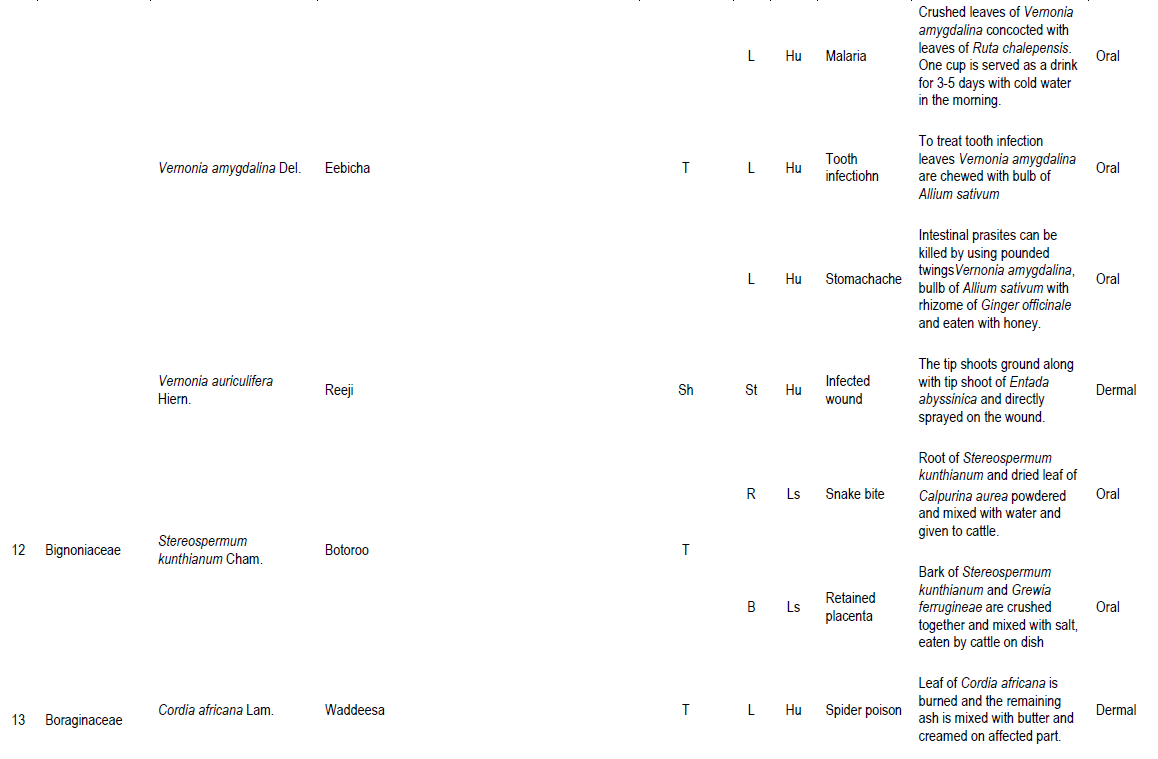

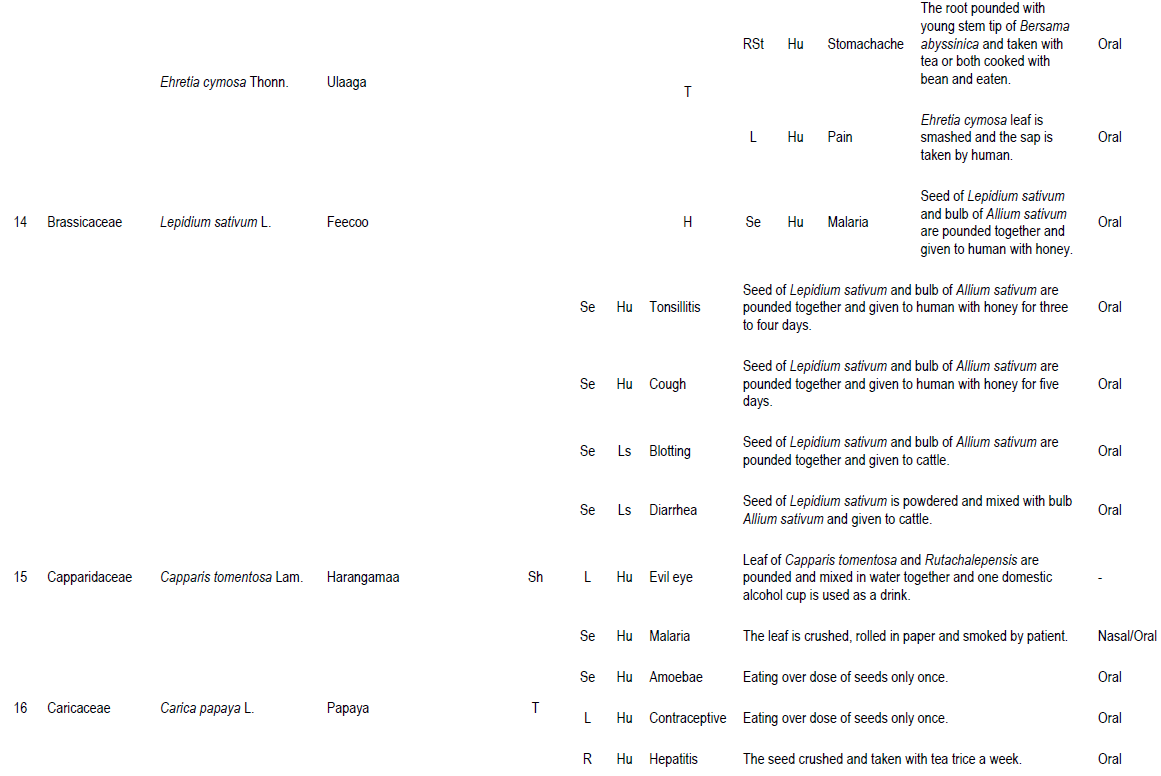

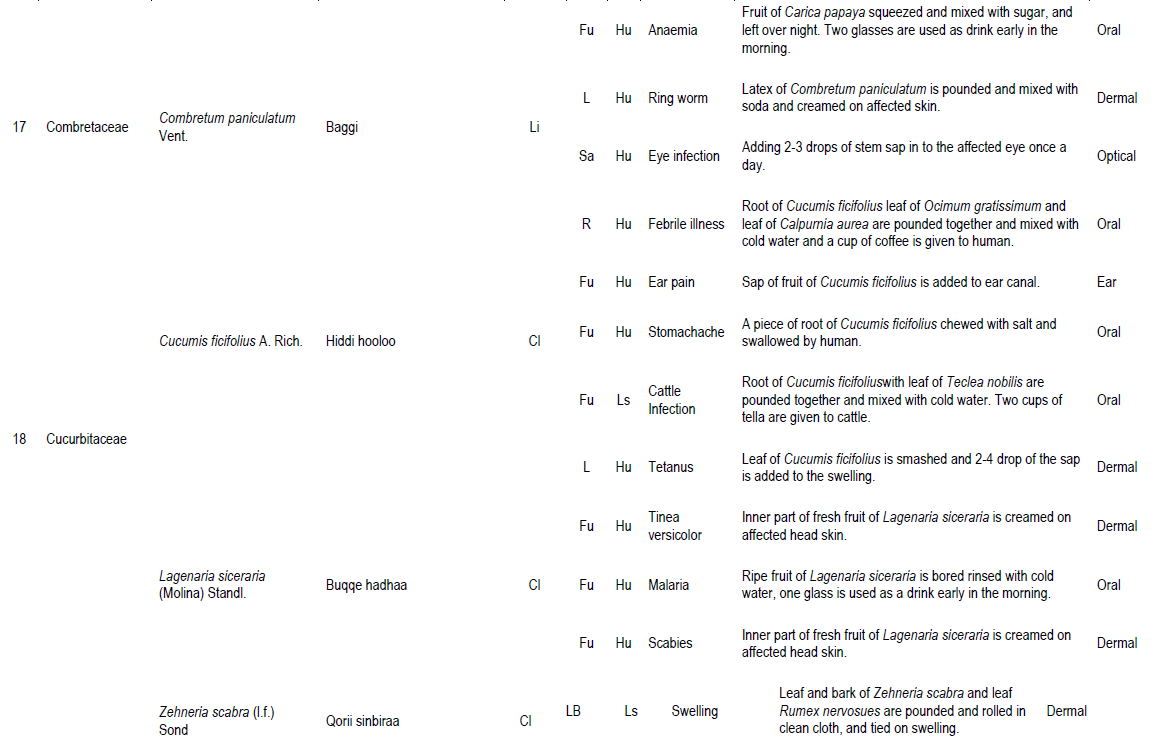

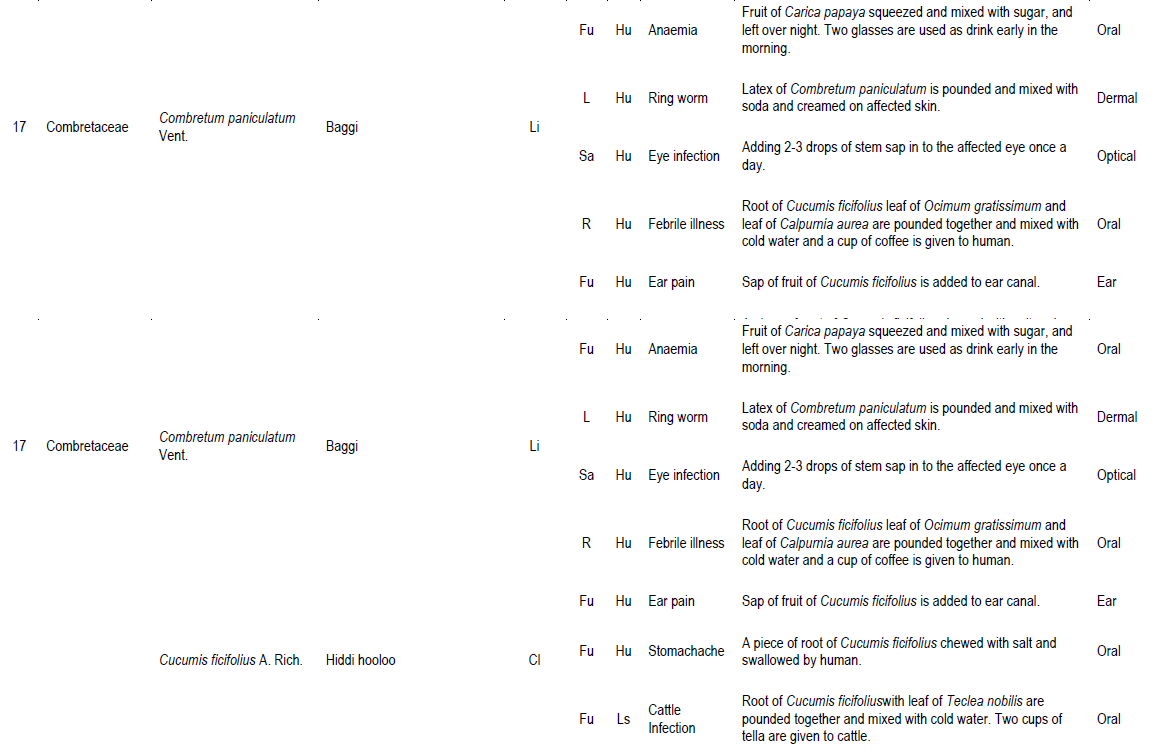

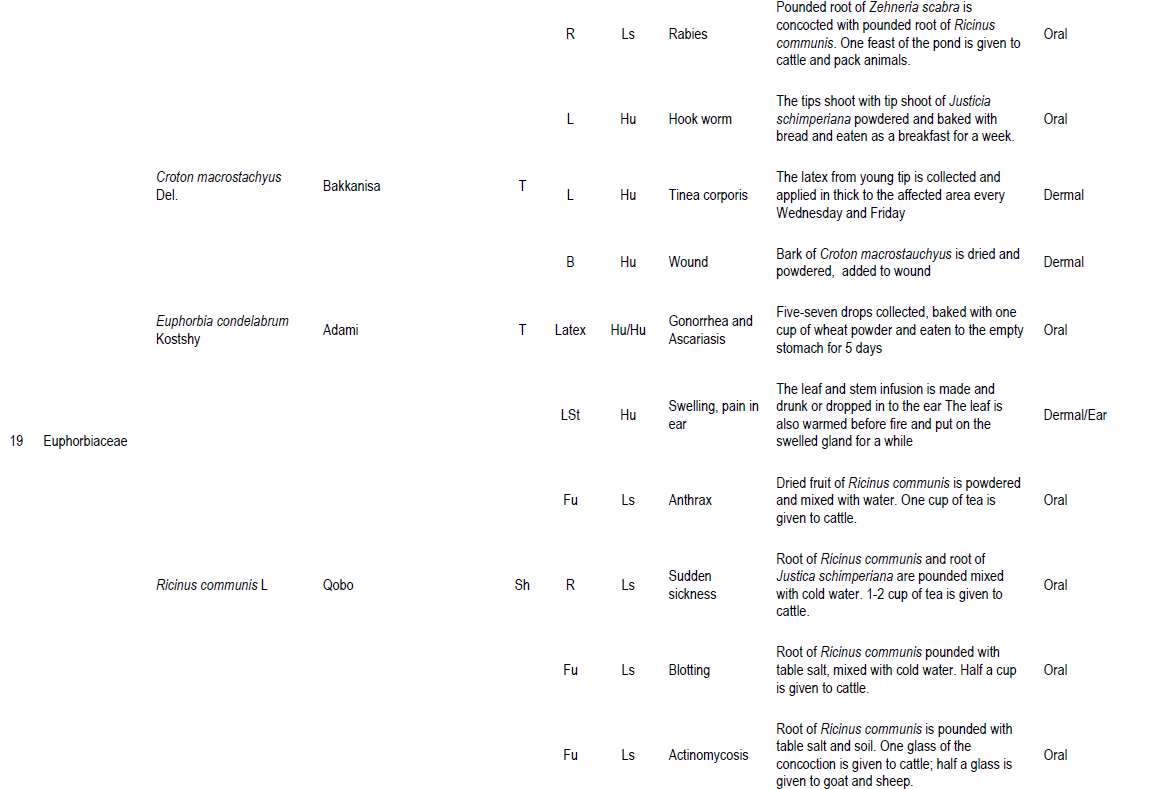

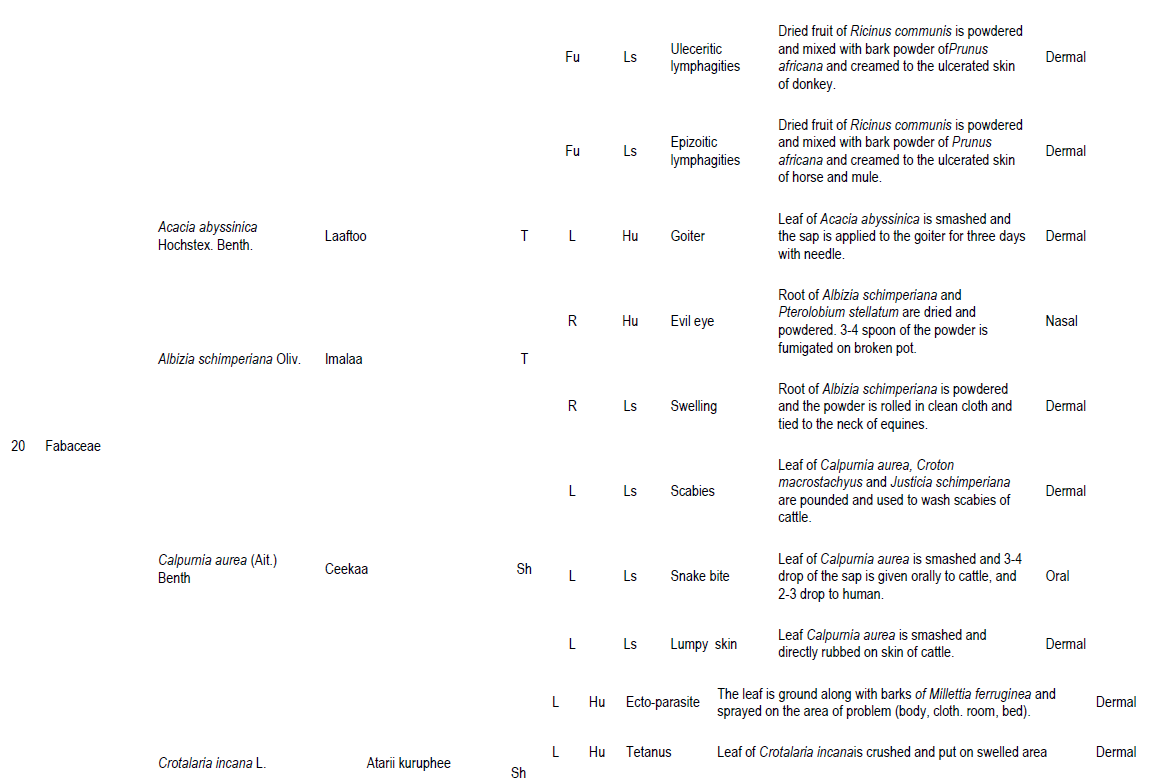

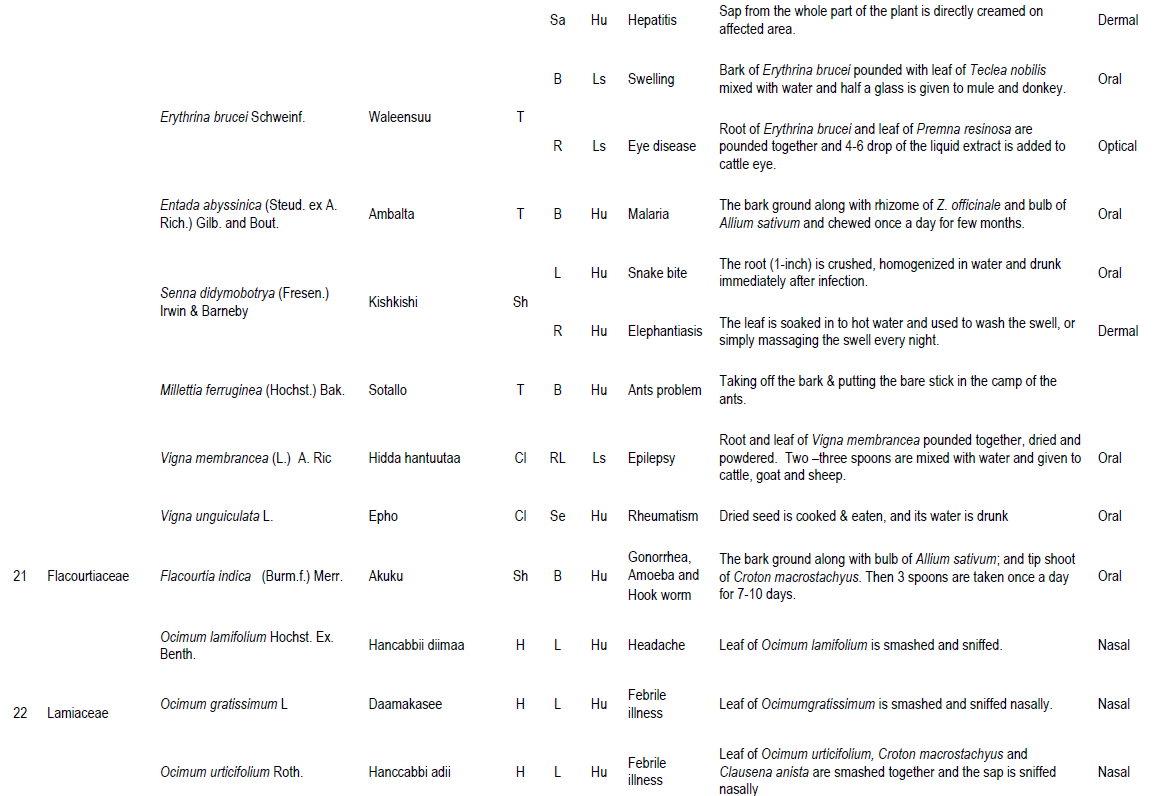

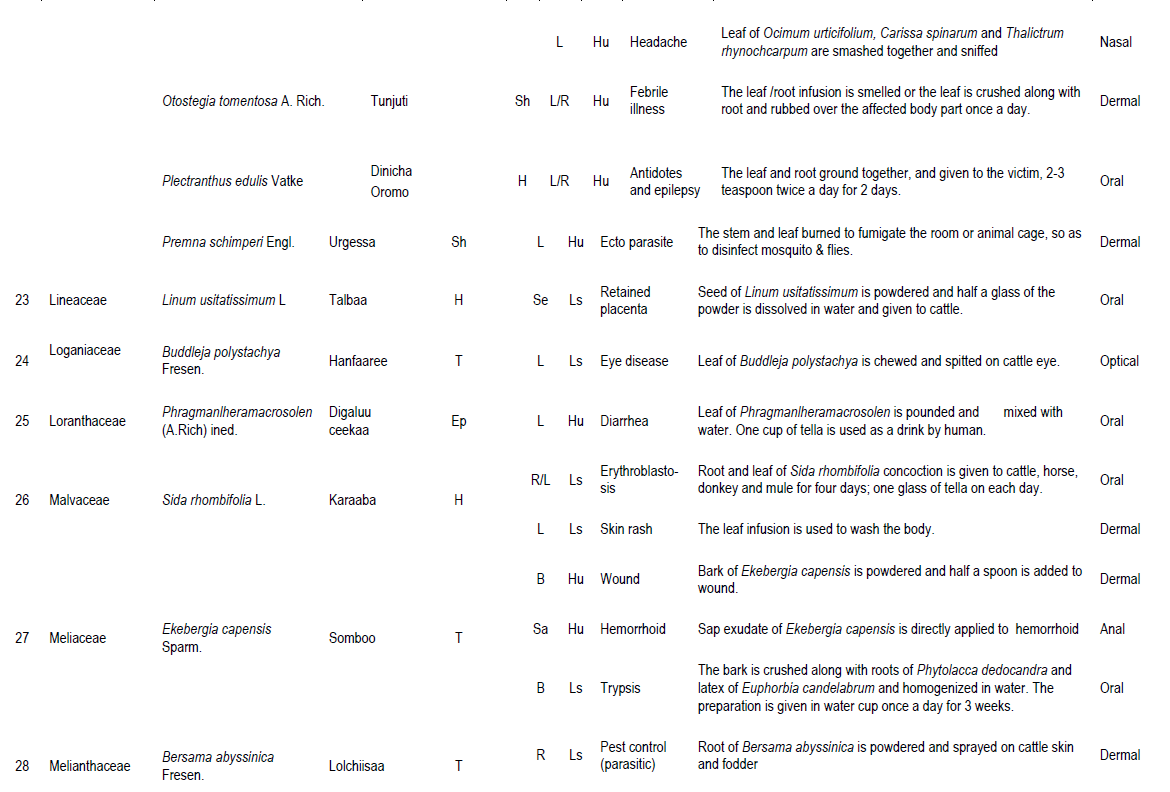

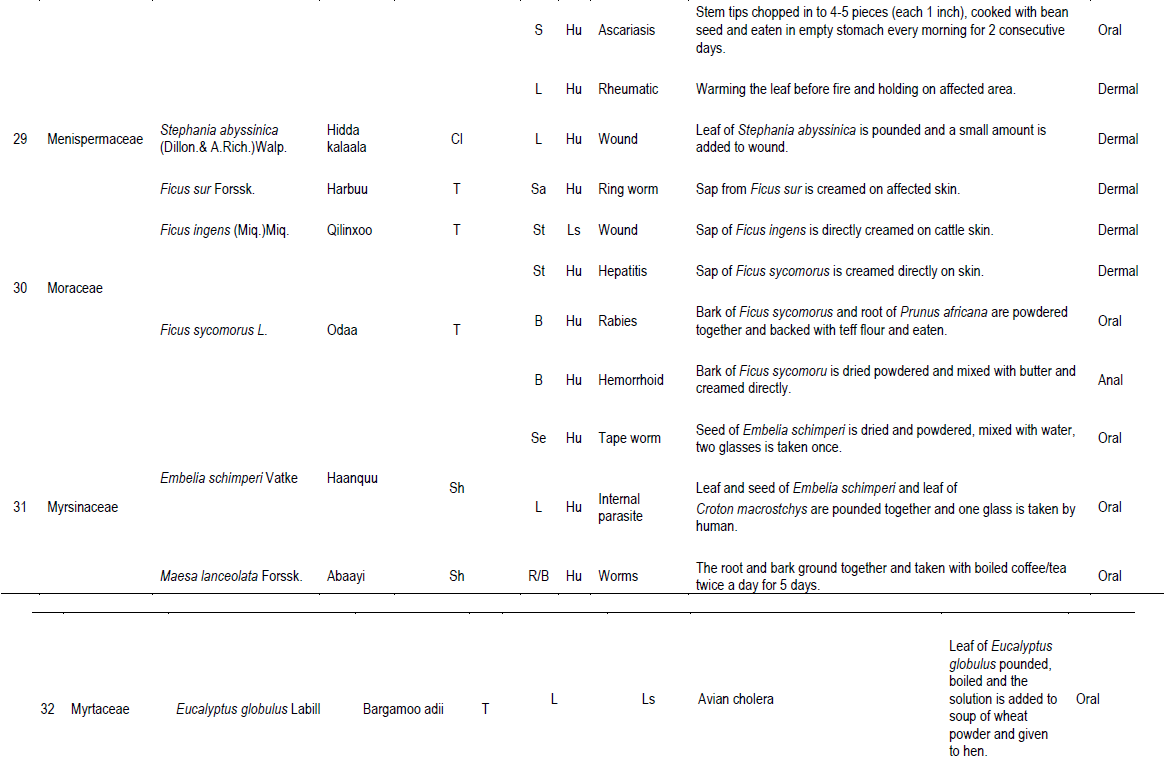

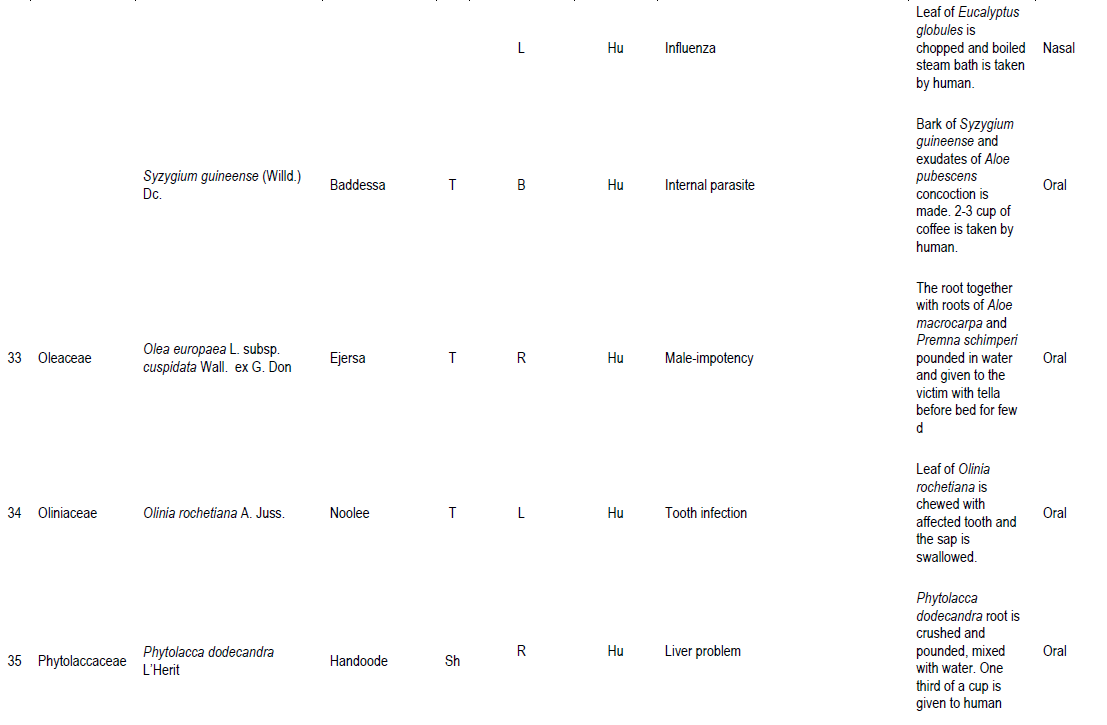

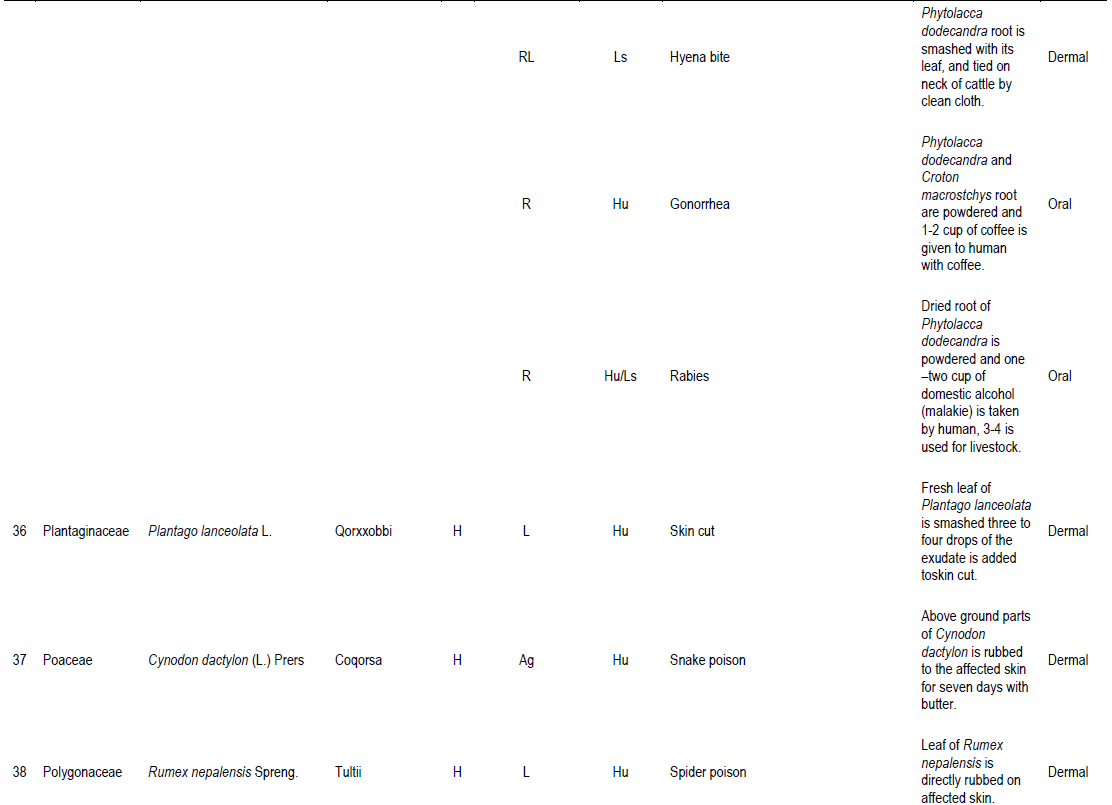

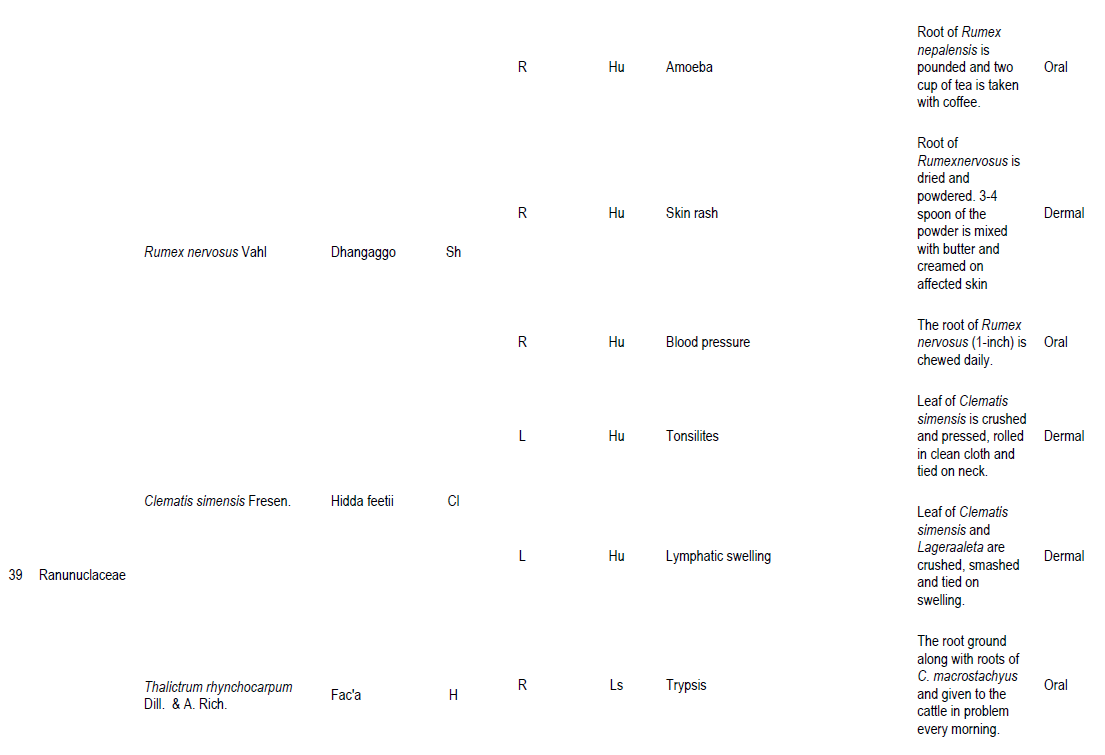

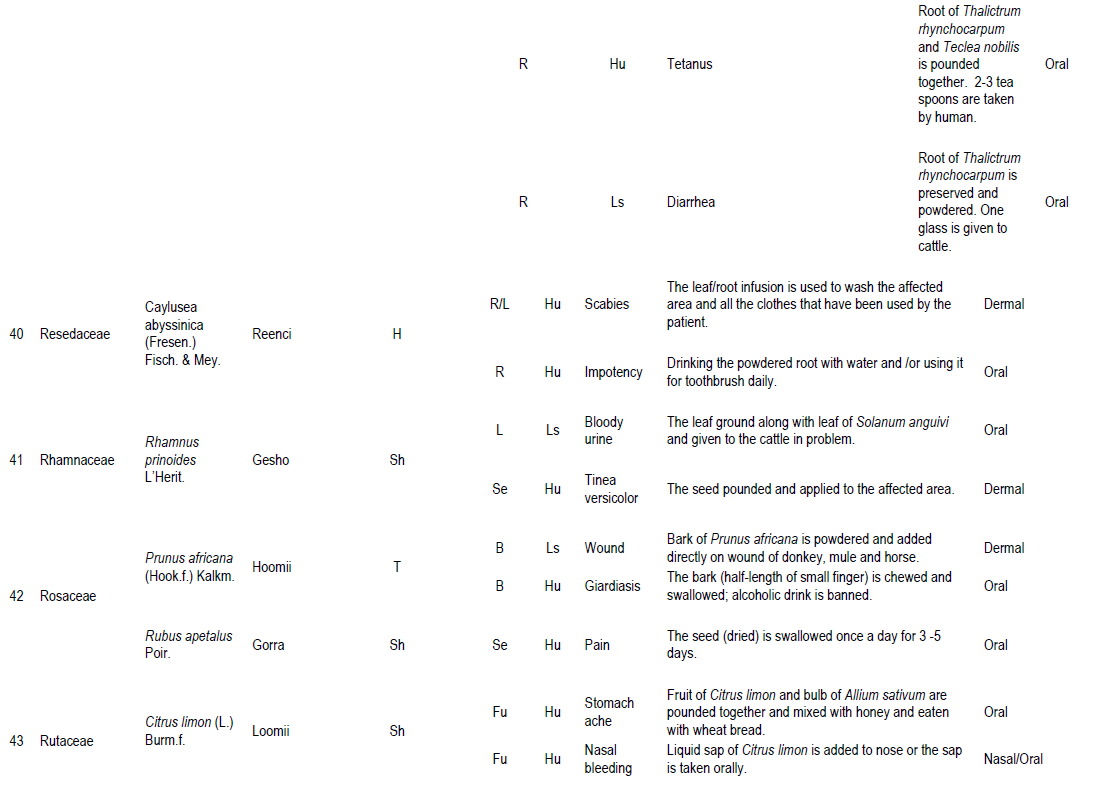

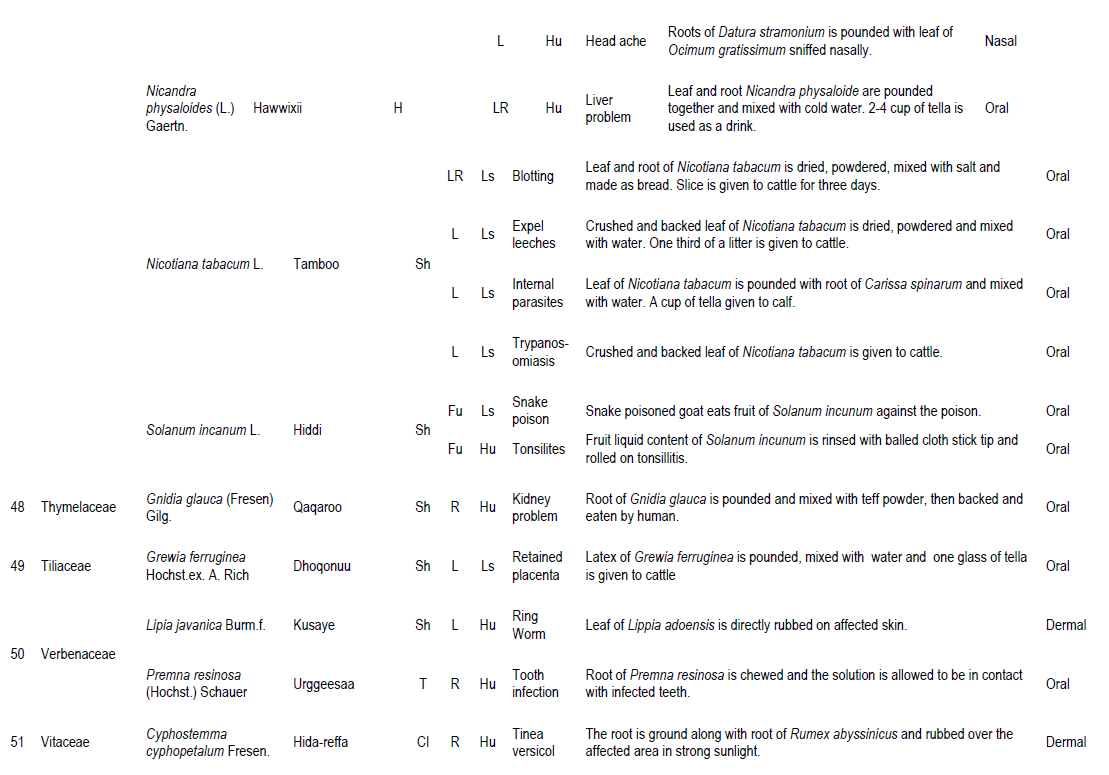

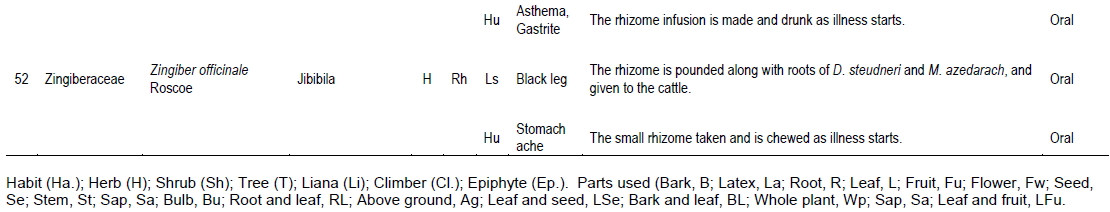

Ethno-medicinal plant species used by people of the study area

In this study, a total of 93 species of medicinal plants were gathered and documented from the study area. The species represented 85 genera and 52 families. Family Fabaceae was represented by 10 species followed by 7 species of Asteraceae and 6 species of Lamiaceae. Rutaceae and Solanaceae were represented by 4 species each; Cucurbitaceae, Euphorbiaceae and Moraceae were represented by three species each. Nine families were represented by 2 species each (Acanthaceae, Araceae, Boraginaceae, Myrsinaceae, Myrtaceae, Polygonaceae, Ranunculaceae, Rosaceae, and Verbenaceae), while the remaining families were represented by one species (Appendix 1). This result showed that Abay Chomen District is rich in medicinal plants as shown by the presence of 93 species exhibiting wide taxonomic diversity. This number of diverse taxonomic groups of medicinal plants and associated ethno-medicinal knowledge has been observed in different regional state of Ethiopia (Getnet et al., 2015; Meaza et al., 2015; Getaneh, 2016). The existence and utilization of such a large number of medicinal plants by people in the study area indicates that the majority of the people used indigenous medicinal practices to take care of medication problems. The study shows that the traditional healers of the study area were found to play great roles in the primary healthcare systems of the local people as they were treating resource poor people who had little access and could not afford the cost for modern medications.

Sources of medicinal plants

Regarding the distribution of medicinal plants about 49 (52.7%) species were obtained from wild followed by 25 (26.9%) species and 19 (20.4%) species from home garden (cultivated and both cultivated and wild). This indicates that the practitioners depend on the wild source or the natural environment rather than home gardens to obtain the medicinal plants, and the activity of cultivating medicinal plants is very poor in the study area. It also indicates that the natural forest of the study area is being over exploited by traditional practitioners for its medicinal plants composition. This finding is similar to the general pattern seen in most medicinal inventories (Getnet et al., 2015; Meaza et al., 2015; Getaneh, 2016) where wild medicinal plants dominate. The local people cultivate some popular medicinal plants in their home garden for the purpose of medicine such as Allium sativum, Schinus molle, Asparagus africanus, Lepidium sativum, Carica papaya, Ocimum lamifolium, Otostegia tomentosa, Rhamnus prinoides and Nicotiana tabacum. This and field observation during data collection clearly confirmed that some traditional healers do not have interest to grow in their home garden some plant species that are used to treat specific ailments in order to keep the secret of their medicinal value. This means that most of the medicinal plants found in the home gardens are those also known to have other uses particularly as food.

Growth form of plants used for medicine

The result of growth forms diversity analysis of medicinal plants reveals that herbs constitute the largest category (29 species, 31.3%) followed by shrubs (28 species, 30.1%). Trees amounted to (26 species, 27.9%). The others included climbers (7 species, 7.5%), epiphytes (2 species, 2.1%) and lianas (1 species, 1.1%). Herbs and shrubs make up the highest proportion (57 species, 61.3%) of the medicinal plant species. This could be related to the fact that these species exhibit high level of abundance and easy to obtain them. Relatively high number of herbs and shrubs for medicinal purpose were also previously reported in Ethiopia (Balcha, 2014; Getnet et al., 2015; Getaneh, 2016).

Medicinal plants and their main uses by the local people

Among the reported medicinal plants of the area, some plants were found to treat different health problems affecting the health of both humans and livestock. Out of 93 medicinal plant species in this study, 56 species (60.2%) were noted to treat only human ailments while 20 species (21.5%) are used to treat livestock ailments. Seventeen species (18.3%) wer used to treat both livestock and human ailments. Informant consensus on these medicinal plants confirms their efficacy against some human and/or livestock ailments.

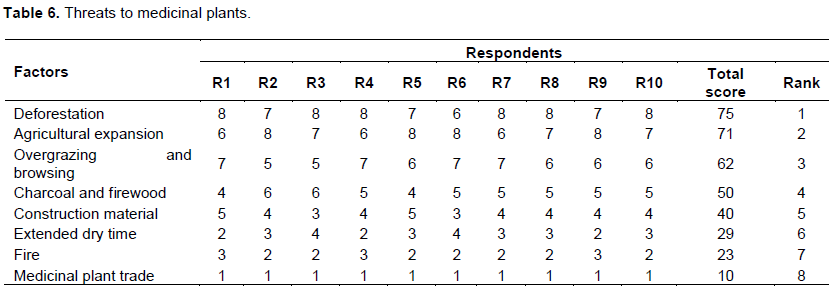

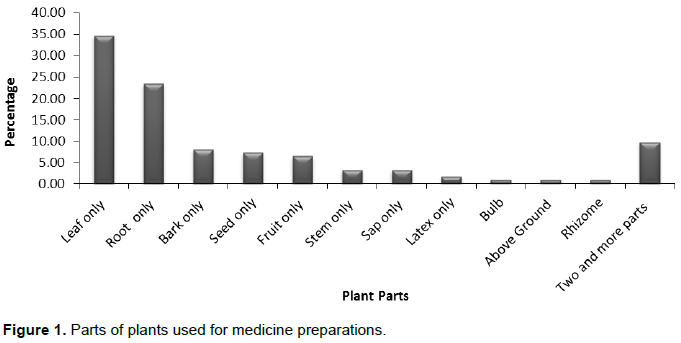

Parts of plants used for medicine

From the total plant parts used for remedy preparation, the leaves and the roots were the most commonly used plant parts in the preparation of remedies accounting for 34.68% (43 species) and 23.39% (29 species) of the total medicinal plants, respectively and lower values for other parts used to treat various health problems (Figure 1). The fear of destruction of medicinal plants due to plant parts collected for the purpose of medicine is minimal as leaves were the leading plant parts sought in the area. Sets of works that were carried out previously elsewhere in Ethiopia also revealed that leaves followed by roots were the common plant parts used to treat various health problems (Mirutse and Gobana, 2003; Abiyu et al., 2014; Balcha, 2014). Herbal preparation that involves roots, rhizomes, bulbs, barks, stems or whole parts have effects on the survival of the mother plants but leaves generally have low impact on individual plants as compared to roots, rhizomes, bulbs, barks, stems or whole parts.

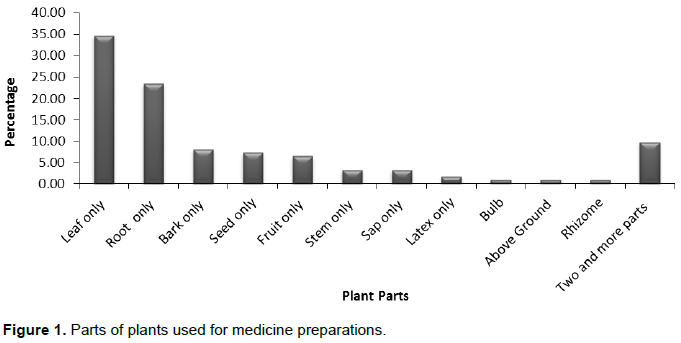

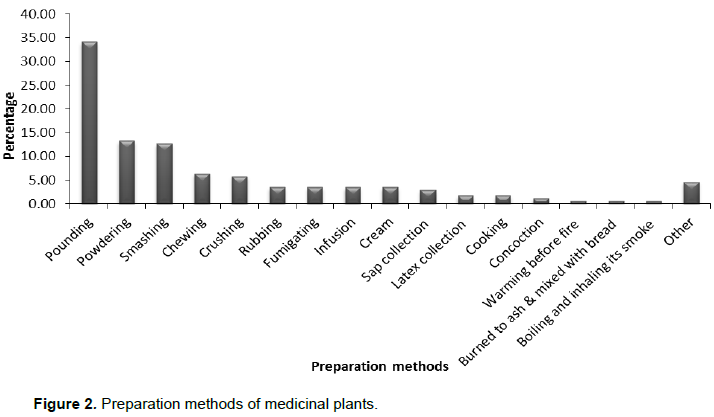

Composition, condition and preparation methods of medicinal plants

In the collection of data concerning the preparation of medicine, informants have reported various skills associated with herbal preparation. These include plant composition (whether single or combined), condition of plant material used (fresh or dry) and methods of preparation. The result showed that most remedies were prepared from single plant species (61.5%) and preparation from combined plant species was about 38.5%. Local people depend on both dry and fresh remedies. In this case, 98 preparations (53.3%) are in fresh form, 54 (29.3%) are dried and 32 (17.4%) are dried and fresh. The dependency of local people on fresh materials put the plants under serious threat than the dried form, as fresh materials are harvested directly and used soon with its extra deterioration with no chance of preservation, that is, not stored for later use. However, local people argue that fresh materials are effective in treatment as the contents are not lost before use compared to the dried forms. The livelihood of most traditional healers relies on fresh materials that have aggravated the decline of rare medicinal plants from the study area according to the informants. Traditional practitioners are collecting medicinal plants with less attention than would be preferred from viewpoint of conservation of plant resource. This finding is significantly similar from all the other findings from other regions of Ethiopia (Debela, 2001; Kebu et al., 2004; Abiyu et al., 2014). The local healers employed several methods of preparation of traditional medicines from plants. The result showed that most remedies were prepared from single plant (61.5%) and preparation from combined plant species was about 38.5%. The result is in agreement with the findings of Dawit (1986) and Debela (2001) in which the single plant preparation were reported to be high and disagrees with works of Mirutse (1999) and Bayafers (2000) in which the combined plant materials were reported to have high proportion in herbal preparation. The local people employ several methods of preparation of traditional medicines. The frequently used methods were pounding, powdering and smashing, respectively. Pounding 59 (34.1%), powdering 23 (13.3%) and smashing 22 (12.7%) are the three main methods of preparation of medicine (Figure 2). The preparation and application methods vary based on the type of disease treated and the actual site of the ailment. The majority of the preparations are made from mixture of different plant species with water and different additive substances like honey, sugar, butter, and salt and milk. These additive substances have different functions, that is, to reduce poisons, improve flavor and as antidotes during adverse effects such as vomiting and diarrhea. Dawit (1986) has also identified the additive substances in herbal remedy preparations with their possible benefits. It was also reported that some medicinal plants are mixed with food and drinks in such manner that, they change their flavor and simple to take. For instance, Lepidium sativum is added with a honey to improve its taste.

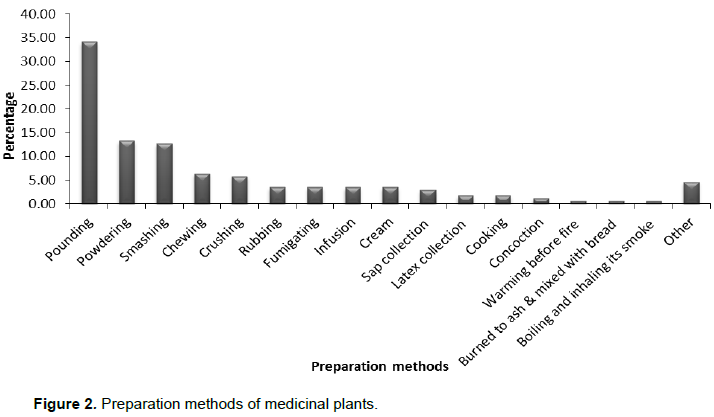

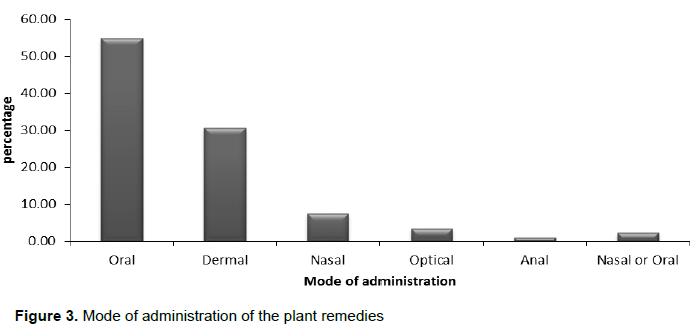

Route of remedy administration and dosage determination

There are various routes of administration of traditional medicinal plants prepared products by the local community. The major routes of administration in the study area are oral, dermal, nasal, anal and optical. Oral administration is the dominant route (54.91%), followed by dermal route (30.64%) (Figure 3). Both oral and dermal routes permit rapid physiological reaction of the prepared medicines with the pathogens and increase its curative power. This fact has been documented by different authors in the other part of Ethiopia (Abiyu et al., 2014; Balcha, 2014; Getnet et al., 2015). In addition, informants reported that there are related restrictions to enhance rapid physiological reaction and to increase its curative power of remedies. For example, a patient who takes remedy against tapeworm should not take any food six hours before and after administration of the medicine. People of the study area used various units of

measurement and the duration of administration to determine the dosage. Local units such as finger length (e.g., for bark, root, stem), pinch (e.g., for powdered plant medicine) and numbers (e.g., for leaves, seeds, fruits, bulbs, rhizomes, flowers and latex) were used to estimate and fix the amount of medicine. Recovery from the disease, disappearance of the symptoms of the diseases, fading out of the disease sign and judgment of the healer to stop the treatment were some of the criteria used in determining duration in the administration of the dosage. However, from the interview made during the study, it was found that there was disagreement among the healers concerning the dosage system used. For drops of example, some informants suggested that four or five the latex from Euphorbia candelabrum is used to treat Ascariasis or gonorrhea, while some suggested that only one drop is enough for the same problem. Still some others suggested that they apply the latex randomly without such measuring system. Although the full dose determination is varying from healer to healer, the dose given depends on age, physical strength and heath conditions. This finding significantly agrees with other findings from other regions of Ethiopia (Dawit and Ahadu, 1993; Abiyu et al., 2014). The he alers never administer treatments that are taken internally to pregnant women.

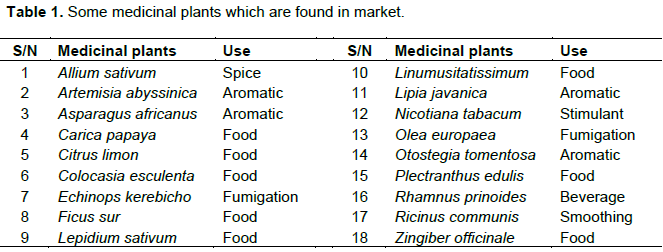

Marketed medicinal plants in the study area

The medicinal plant material found being marketed in the open markets for medicinal purpose was Nicotiana tabacum in the treatment of livestock disease. In addition to this, some medicinal plants are sold in the market for other purposes and most of them are sold as food (Table 1). Selling medicinal plants in the market are not a common cultural activity in local markets of the study area. But medicinal plant like Hagenia abyssinica (dry flower) is sold in the market for its medicinal purpose. Some fresh collection of Echinops kerebicho, Artemisia Abyssinica and Allium sativum are also marketed in a local community for their fumigation, aromatic and spice value, respectively. These results are consistent with the findings of various ethnobotanical researches elsewhere in Ethiopia (Getnet et al., 2015).

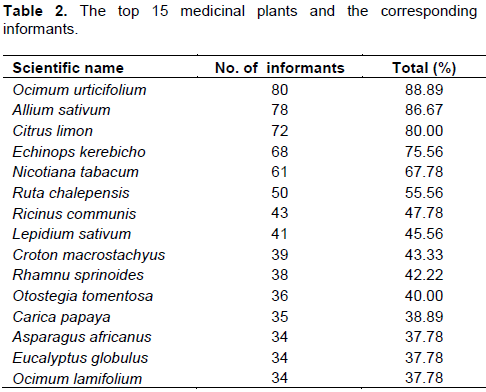

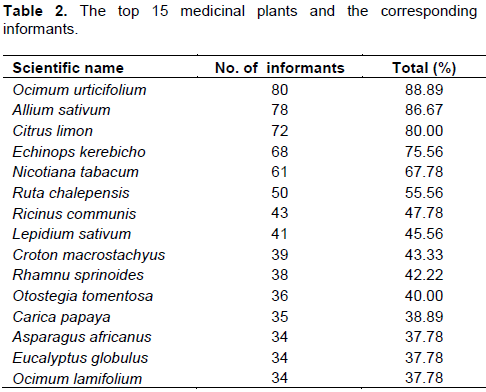

Informant consensus

The results of the study showed that some medicinal plants are popular than the others, in view of that, Ocimum urticfoluim (Hancabbii adii) took the lead where it was cited by 80 informants for its medicinal value for treating fibril illness. Allium sativum, Citrus limon and Echinops kerebicho are cited by 78, 72 and 68 informants ranking 2nd, 3rd and 4th, respectively (Table 2). The latter three species are used for treating a series of different health problems. The action of plant extracts on different health problems may explain the broad-spectrum nature of plants, while their action on a particular problem explains their narrow spectrum nature. Popularity of these medicinal plants according to key informants is due to their wide range of diseases they treat or due to the abundance of the plant in the area for easy access. The case of Ocimum urticfoluim and Allium sativum can be cited for their abundant distribution in the area. With this, other medicinal plants mentioned by four or more, scoring percentage greater than 50 and those frequently used ones for treatment of more than two ailments are given in Table 2.

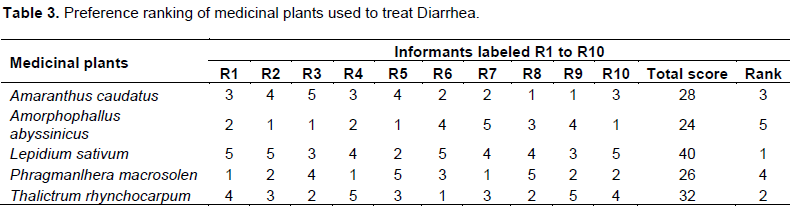

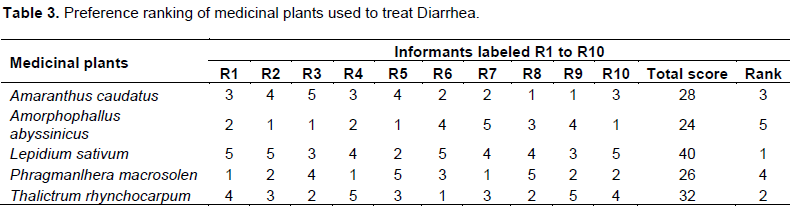

Preference ranking

When there are different species prescribed for the same health problem, people show preference of one over the other. Preference ranking of 5 medicinal plants that were reported as effective for treating diarrhea was conducted after selecting 10 key informants. The informants were asked to compare the given medicinal plants based on their efficacy, and to give the highest number (5) for the medicinal plant which they thought most effective in treating diarrhea and the lowest number (1) for the least effective plant in treating diarrhea. Preference ranking for seven medicinal plants used to treat gonorrhoea (Table 3) shown that Lepidium sativum ranked first and hence is the most effective medicinal plant to cure diarrhea. The second and third most preferred medicinal plants against this disease are Thalictrum rhynchocarpum and Amaranthus caudatus, while the least preferred species compared to the other five species are Phragmanlhera macrosolen and Amorphophallus abyssinicus according to informants.

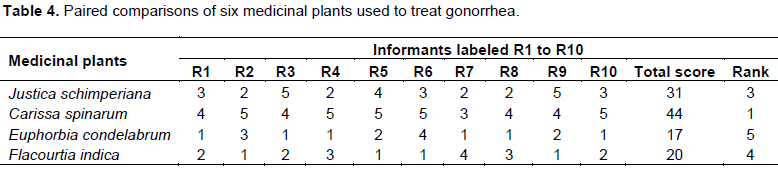

Paired comparison

For medicinal plants that were identified by the informants to be used in treating gonorrhea, a paired comparison was made among five of them using ten informants to know their rank (Table 4). Carissa spinarum, Phytolacca dodecandra, Justica schimperiana and Flacourtia indica were ranked 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th, respectively. Euphorbia condelabrum are less preferred and less efficacious compared to the other four species.

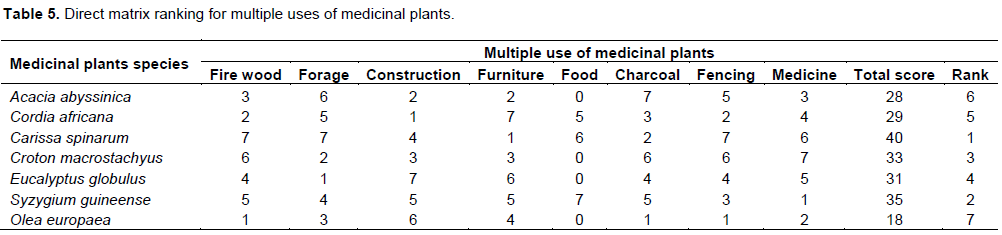

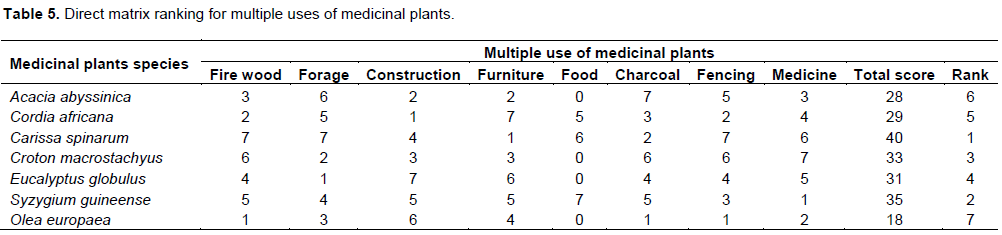

Direct matrix ranking

In this study, a number of medicinal plants were found to be multipurpose species being utilized for a variety of uses. The common uses include medicinal, fodder, food, firewood, construction, charcoal, fencing and furniture making. Seven commonly reported multipurpose species and eight use-categories were involved in direct matrix ranking exercise in order to evaluate their relative importance to the local people and the extent of the existing threats related to their use values (Table 5). The results show that the local people harvest seven multipurpose species mainly for firewood, fencing, medicine, charcoal, construction and furniture with the rank of 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th and 7th, respectively. Thus, the long-term survival of the top-ranked species are under question, as the daily demand of the local society is usual and continuous with lesser rate of re-plantation, except for Eucalyptus globulus. This is evidenced by the high rate of loss of Carissa spinarum, Syzygium guineense and Croton macrostachyus in the area.

Fidelity level index

Confirmation or consensus could not be taken as a single measure of the potential efficacy of any medicinal plant in fidelity level index. Thus, efficacy is not the only factor that influences the informant choice but abundance of a given plant and prevalence of disease in the area can affect informants choices. As malaria is one of the frequently reported diseases in low land areas (Fincha Sukuar project and Sementegna camp area) and less frequent in high land areas (Achane, Kolobo, Gengi Ketela and Jare). Different number of informants from the two areas for malaria case reported the use of Allium sativum as a remedy.

The fidelity level index was calculated for Allium sativum for the two ecological areas. A total of 13, 17 specific and general use for Allium sativum were reported by informants from Achane, Kolobo, Gengi Ketela and Jare. While 17, 18 specific and general uses for Allium sativum were reported by informants from Fincha Sukuar project and Sementegna camp area. Use reports of informants from Achane, Kolobo, Gengi Ketela and Jare were compared with informants from Fincha Sukuar project and Sementegna camp area to assess the fidelity level of Allium sativum (FL=IP/IU). From the comparison, it was found that the fidelity level of Allium sativum for malaria treatment by Achane, Kolobo, Gengi Ketela and Jare informants was 76.4%, while for Fincha Sukuar project and Sementegna camp area was 94.4%. Thus, the medicinal value of Allium sativum is high in Kola areas compared to Woinadega zones.

Indigenous medicinal plant knowledge development and sharing

Traditional knowledge of medicinal plants in most cases is passed along the family line from parents and other intimates, especially gifted family members (which they described as "Harki isa kan hojeetu", meaning one whose hands are skillful and effectual). Some of the traditional knowledge is generated through the community by listening and practicing while some copied secretly and systematically by following and observing the knowledgeable individuals at times of medicinal plant collection and preparation. Others develop and transfer their medicinal plant knowledge to generations by following up healers after seeking treatment of their family members. In very few cases, individuals developed their medicinal plant knowledge upon careful observation of domestic carnivores, especially the cat, which immediately consumes medicinal plant parts upon preying on poisonous snakes, scorpions and spiders. One healer reported his

discovery in this way of Vernonia adoensis for the treatment of snake poison. Medicinal plant experts have developed some traditional medicinal plant knowledge from observations of animal feeding to know the plants that are never consumed, which hints at plants not for internal use to ensure safety of the vital organs but rather used for the treatment of dermal ailments such as wounds because of their possible toxic nature. Furthermore, experienced medicinal plant experts create new medicinal knowledge by relating the plant odour with previously known medicinal plants. Some healers were seen recording ethno-medicinal knowledge in small notebooks during fieldwork, which may testify their curiosity and keenness to develop and transfer indigenous knowledge to the next generation.

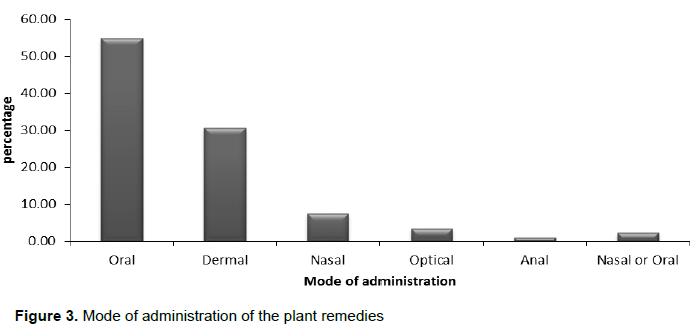

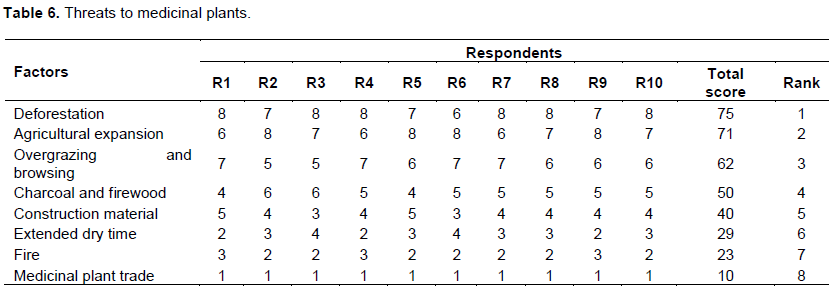

Threats to medicinal plants and conservation practices

In Abay Chomen District, various factors that were considered as main threats for medicinal plants were recorded by interviewing the informants. The major factors claimed were deforestation (1), agricultural expansion (2), overgrazing and browsing (3), trading charcoal and firewood (4), construction material (5), drought (6), fire (7) and medicinal plant trade (8) (Table 6). These results are consistent with the findings of various ethnobotanical researches elsewhere in Ethiopia, such as that of Balemie et al. (2004), Ermias et al. (2008) and Getnet et al. (2015) indicates some similar investigation. The effort to conserve medicinal plants in the district was observed to be very poor. Some traditional practitioners have started to conserve medicinal plants by cultivating at home gardens, though the effort was minimal. Traditional beliefs in the area also have their own unintentional role in conservation and sustainable utilization of medicinal plants. However, giving conservation priority for identified threatened medicinal plants, promoting in-situ and ex-situ conservation of medicinal plants in Abay Chomen area as well as supporting the district's Traditional Healers Association, by providing funds, land for cultivating medicinal plants and assisting their activities with professional guidance helps to conserve the fast eroding medicinal plants of the study area.