The Local Health Councils (LHC) in Brazil is one of the most interesting policy innovations of contemporary Brazilian health reform. Formulated at a time of intense social and institutional change, the LHC can be understood as a social policy resulting from the struggles against the military dictatorship (1964 to 1985) and the battles for hegemony in conducting the re-democratization process. Part of the major health reform that created the Unified Health System (UHS) and produced important changes in the institutional design of the Brazilian state, the Local Health Councils originate in a set of laws that promote decentralization and popular participation, allowing Brazilian citizens to oversee and deliberate about health issues on the local level. Considering that not all policymaking processes are logical or rational in an instrumental sense, and considering that the government capacity is very significant for successful formulation and implementation, this paper adopts the "model of policy capacity" (Howlett et al., 2015) to explain the situation of "Poor Policy Design Space" of the Local Health Councils in Brazil.

The local health councils in Brazil: Historical approach

The creation of Local Health Councils (LHC) in Brazil is one of the most interesting policy innovations of contemporary Brazilian health reform. The LHC is a policy created inside the Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde, or SUS), considered one of the largest public health systems in the world. Sociology studies have linked the origins of the health councils to, among other factors, the actions of an organized society in the period of 1970 to 1990, emphasizing the struggle against the military dictatorship. Importantly, the movement for Sanitary Reform and its historical struggle against dictatorship was in favor of re-democratizing health issues and guaranteeing health as a citizen’s right and a duty of the state. In this way, the advancement of health reform in Brazil was incorporated in the larger movement towards greater public participation and democracy in government.

In the mid-1980s, a series of social and political movements across Brazil opposed the dictatorial regime, aiming to increase public participation in government and make public policy more effective through an open and democratic regime. These demands, previously repressed by the military government, gave rise to participatory

management policies in Brazil when the dictatorship was deposed in 1985. This process introduced the concept of "social control" on social policies in Brazil.

In the face of a regime legitimacy crisis, several gaps in health care access and provision were present across the country in the mid-1980s. After 21 years of military legacy (1964 to 1985), the progress in health policy had resulted in disproportionate improvements that were limited to urban areas. Primarily, this was a consequence of a centralized, selective, and market-oriented public health system (Cortes, 2002; Santos, 2013). Inequalities in health care access and provision in the 1990s led to an intense debate concerning the weaknesses of the welfare state and the formulation of new social policies to solve these problems. The 1988 Constitution, drafted during the re-democratization process, attempted to solve national problems through a combination of universal social policies, decentralization, and popular participation with an innovative policy design that guaranteed participation employing new social policies. Regarding health care, the new constitution established health as the right of all, defined its provision as the duty of the state, and guaranteed the right to popular participation in local public health management with the creation of the new health care system, the Sistema Único de Saúde (Gohn, 2003; Cortes, 2002; Coelho, 2004). The SUS is a universal, publicly funded, rights-based health system, that guarantees community participation in government decision-making, reflecting the belief that decentralization and municipal control were the best approach to integrated health care (Brasil, 1990a).

The Brazilian Health movement established four propositions with the creation of the SUS. The first proposition aims to establish health as a right of every citizen, regardless of monetary contribution or employment. Contrary to the previous model, the proposal did not deny any Brazilian citizen access to the public health system. The second proposition stipulated that health actions should ensure the population's access to preventive medicine and should be integrated into a unique system. The third proposition dealt with the decentralization of management, both administrative and financial, while the fourth proposal emphasized the public control of health decisions. Through the SUS, health care policy and the provision of services have become universal and responsive to the needs of all Brazilians. With the recognition of a health care system based on universal right and popular participation in management at the local level, the social contract between citizens and the government appears to have been strengthened with respect to health care. The SUS laid the groundwork for the establishment of institutionalized mechanisms for citizen engagement at all Brazilian government levels (municipal, state and national). One of the most important instruments that the SUS created for improving citizen participation, decentralization of social policies and universal access was the local health councils and national and local conferences. Designed as an overall strategy for decentralizing and increasing the quality of health services, the Local Health Councils (LHC) in Brazil allow citizen participation in the health policy process under advisory bodies that operate at all levels of government and that bring together different societal groups to monitor Brazil’s health care system. Local health councils became a permanent and deliberate method of controlling public health care implementation (Brasil, 1990b).

The LHC are responsible not only for implementing health programs but also for taking suggestions from users, the market and interested groups to the various levels of government: municipal (local), state and federal. They make decisions, act as consultative bodies and exercise oversight. They also approve annual plans and health budgets and assist municipal health departments with planning, establishing priorities and auditing accounts. For that reason, these organizations have increasingly become an object of investigation and theoretical reflection of researchers (Gohn, 2003; Cortes, 2002; Coelho, 2004; Moreira and Escorel, 2009; Brasil, 2013). Two laws are important in understanding the creation and rules of the Health councils in Brazil: the Organic Health Law (8080/90) and Law 8142/90. The Organic Health Law (8080/90) determines rules for delivery service of SUS. According to OHL, the management, actions, and public services must follow the structural principles for health policy established by the federal constitution, as described earlier. Another Health regulation, Law 8142/90, defines health councils and conferences as mandatory events, on national, state and municipal levels, thus, institutionalizing the space for popular participation. Together, the laws make societal participation in the health sector a central means for democratization and decentralization, combined with the rule that makes the participative decision-making an official process.

Under Law 8142/90, the Local Health Councils are responsible not only for taking government projects to the population but also for taking suggestions from the population to the various levels of government: municipal, state and federal. The LHCs make decisions, act as deliberative bodies, and exercise oversight. They inspect public health accounts, demand accountability in service delivery and budgeting, and exert influence over how public health resources are spent. Additionally, they assist municipal health departments with planning, establishing priorities and auditing accounts. In Brazilian federalism, a major portion of local budgets is provided by funds transferred from the federal government to municipalities. These transfers are mandated by the Constitution and are the most important source of municipal revenues in Brazil (especially for smaller municipalities). As the capacity of local governments to provide services in Brazil is highly dependent on federal resources, the Local Health Councils are one of the most important policy tools for providing resources to local health systems (Cortes, 2002; Gohn, 2003). Under Law 8142/90, federal transfers became contingent upon the LHC’s existence. The councils must verify accounts and notify authorities of any irregularities. If a local council does not exist, or if the plan is rejected, the city does not receive health funding from the Federal Health Ministry.

Data, composition, and design: Analytical approach

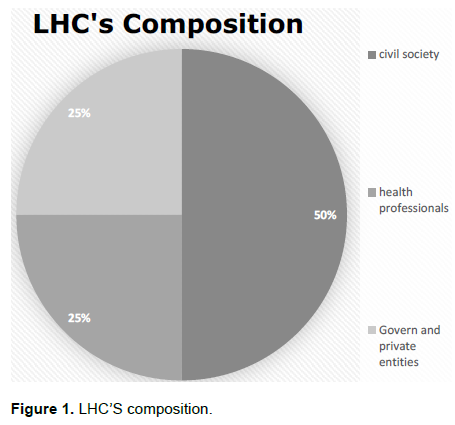

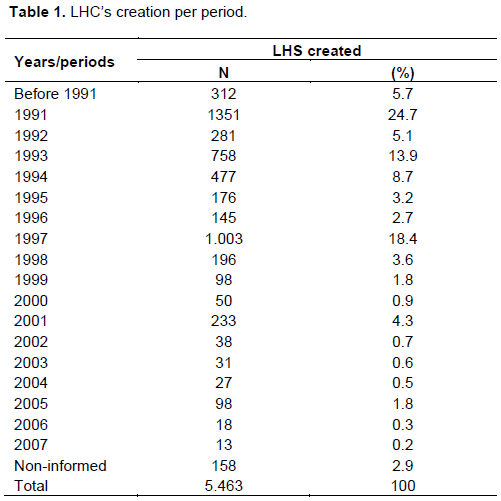

According to Moreira and Escorel (2009), 5,463 LHCs had been created by 2007, with the period from 1991 to 1997 showing the greatest number of local councils created (76.7%; Table 1). These years were marked by the initial impact of the rules making the LHC required by Federal Law (8142/90). An updated database of the Brazilian National Record of Health Councils shows that in 2010, 5,564 Brazilian cities had a local health council or 98% of all cities. In 2015, 100% of municipalities have councils. One of the most important actors on a Health Council is the "counselor". Counselors are elected in the first meeting and represent a specific composition of members. For every representative, there is a substitute. In addition to the novelty of these organizations with respect to actuation and rules, the council’s composition is particularly noteworthy. Members of the public (the SUS users) are granted parity in relation to all other sectors. This means that municipal councils are composed so that members of the public make up half of the council (50%), health professionals make up a quarter (25%), and government or non-governmental entities make up the rest (25%). The non-governmental entities include churches, social movements, scientific institutions, and other interest groups, such as (carriers of specific diseases, medical companies, and associations (Figure 1).

The main objective of this design is to encourage sharing perspectives and ideas regarding local health issues and possible solutions in a community (Moreira and Escorel, 2009). Through a process of debate, problem identification, selection of alternatives, the conta-giousness of conflict, formulations, and reformulations, citizens, health workers or government staff try to gain the attention of the others about their own ideas. This process, marked by ambiguous ideas and conflicting interests, can create enough consensus about the importance of particular health issues or possible solutions that it results in policy change. And when these actors are not able to garner enough attention or agreement about the importance of a problem or a possible solution, they often continue to fight for their interests in other areas and at others LHC meetings (Gerschman, 2004; Cortes, 2002). As described above, the responsibility for chairing, convening and establishing the dynamics of meetings, as well the rules of the internal organization, falls on elected councilors, whose mandate is established and voted on during the preparation of internal regiment. The size of council meetings varies, depending on the degree of engagement and interest in the proceedings by those who do not occupy title positions. The number of formal representatives varies with the size of the area being represented.

Design or non-design in policy formulation processes: Using the model of policy capacities to analyze the local health councils in Brazil.

The history of the local health councils in Brazil demonstrates a deliberate and conscious attempt to set goals for problem identification by various social and political actors. It also shows the use of an instrumental form of policy tools to respond to a given problem. Inserted in the process of choices and policy formulation, policy tools are an important element influencing the policymaking process (Smith and Ingram, 2002). The choice of the tools reflects the way policymakers intend to achieve their goals (Hood, 1986). Thus, the choice and design of the policy tools can indicate the distance as well as the approximation of the original objectives. Policy tools structure public policies and can be described and classified according to several typologies (Peters, 2000). Three decades of literature on policy tools have led to numerous typologies, including Lowi arenas (1966; 1972); "NATO", composed of four characteristics (Hood, 1986); Salamon’s (2002) proposed split into 14 basic types; as well as the 63 instrument types proposed by Kirschen (1975). (Howlett et al., 2009)

According to Christopher Hood’s typology (1986), it is possible to identify the use of a complex mix of tools in the formulation of the LHCs. As mentioned earlier, the transfer of resources for health from the federal government to municipalities is conditioned on the existence of active LHCs.

Thus, if the municipalities do not comply with the legislation that ensures the existence of the councils, no transfer of funds is made. This is an example of the use of treasury instruments as policy tools: the policy design uses subsidies, grants, tax incentives, and loans as tools in order to condition the transfer of funds for health in cities. Through the use of the tools, policymakers, non-governmental organizations, and other actors involved in the formulation process demonstrate an awareness of the effects of using the policy tool in order to ensure the implementation of these policies. As a result, Moreira and Escorel (2009) Table 1 shows that just ten years after their creation, LHCs covered and served more than 80% of Brazilian territory. The internal organization of councils is determined by an electoral process to choose “councilors” to compose the governing body of health Councils. These are unpaid volunteers. The composition should be made via the election of representatives in accordance with the principle of parity, with 50 percent of seats occupied by SUS users (civil society); 25% by organizations of health workers; and 25% by the government or non-governmental entities. The creation of organization and authority tools attempted to solve or at least mitigate, the knowledge of decision makers about the disparity of interests and political forces in the policy process. The parity of the actors who represent and manage the councils is both an example of the knowledge of reality and future problems, but also reflects an understanding of how the use of specific types of instruments can affect the target group's behavior and compliance with government goals. If such parity requirements did not exist in the design of the councils, the decentralization of the development of the local political process may have been restricted to self-interested actors that had a greater political power to access local directors and greater bargaining power (among others advantages).

Conceptually, the difference between design and non-design situations are established between those who understand the process of the political decision as rational, intentional and instrumental, and those who assume that the policy and decision-making process is inherently ideological and hence, irrational. That is, on the one hand, there is a recognition that policymakers should base their analysis, as far as possible, on logical behaviors, knowledge, and experience, which requires both analysis and evidence from the government. On the other hand, there is a recognition that not every policymaking process is driven by logic or knowledge and intent; there may be an absence of instrumental logic "in which formulators or decision-makers, for example, may engage in interest-driven, or, more extremely, might engage in venal or corrupt behavior in which personal gain from the decision may trump other evaluative criteria” (Howlett et al., 2009, 2015). As mentioned in the first section of this paper, it is possible to identify clearly the government's intention when the LHC model was implemented. It is also apparent that in the case of the LHCs, decision-makers applied knowledge of the instruments and tools that would be required for the success of this policy. Thus, the formulation of the LHCs in Brazil does not seem to be a case of a non-design-based process; it appears to be more consistent with a design-based process. The actors involved have provided strategic issues and chose treasury instruments, control, and authority that resulted in a rapid process of implementation of the policy in more than five thousand Brazilian municipalities.

However, although the implementation of the LHCs may be a case of a design-oriented process, even when these values are an important aspect of the process of formulation and implementation, successful policymaking and effective resolution of health issues requires a high degree of government capacity. According to Moreira and Escorel (2009), although, LHCs are intended to be inclusive and participatory, in practice they seem to have little impact on the health policymaking process in Brazil. It is not possible to say whether the creation of the Local Health Councils in Brazil, as part of the reform of the Brazilian health system, has improved the quality and accessibility of care services offered, or if it has instead intensified the territorial and social inequalities that already existed. (Moreira and Escorel, 2009). Considering the main objectives of the Councils, decentralizing decision-making for local health services; implementing health programs; creating a forum for participation by users; communicating local health priorities to the various levels of government: municipal (local), state and federal; acting as consultative bodies and exercising oversight; approving annual plans and health budgets; and assisting municipal health departments with planning, establish priorities and auditing accounts we conclude that a rethinking of LHC governance structures, processes, membership, and oversight is required not for lack of intent, but above all, because of a lack of government capacity. The main problems of the LHC in the municipalities lie in the absence of management capabilities that allow the use of state resources as well as the political capacities of elected councilors, and local managers. While the LHCs do create an effective space for public participation, the structure of the councils and the availability of resources and information are precarious, if not absent or biased. As a result, the actual policy decisions and implementation by these councils may be largely unsuccessful. Either at individual, organizational or systemic level, a context of low government capacity in implementing the policies, coupled with a complex set of policy tools, has left large regional differences in the health outcomes of more than five thousand Brazilian municipalities.

This paper aims to revisit the history of one of the most important Brazilian policy: The Local Health Councils. Throughout this explanation, we not only recovered the way in which this policy was created, but we analyze it according to the model of "policy formulation space". We focus our analysis on the policy design in its performance, instruments, actors, conditions, delivery but, also, on its vulnerabilities. There is no doubt that municipal-level LHCs with its participatory nature, have contributed to the democratization of decision-making in the health sector. However, greater participation of users does not guarantee the reduction of inequities in promoting health care for the population. The movement toward a more successful, innovative policy requires at least an increase in capacity building. The Local Health Councils are an example of innovation and improvement in the formulation of Brazilian health policy. Previously almost nonexistent, fragmented and with a great disparity between social classes, their design presents a multi-level composition (involving the federal government and local government); multiple actors (SUS users, managers, and health professionals) as well as multiple tools (treasury, organization, and authority). However, although the focus lies in improved policymaking through decentralization, the establishment of closer operational links between national and sub-national actors must be ensured, and systemic resources and political support made available to ensure the actual execution of those individual skills and competencies at the local level. If change is resisted, the LHCs will remain largely limited to a good idea in theory that is disappointing in practice.

Based on model of “policy formulation space”, it was concluded that the Local Health Councils in Brazil are an example of the "Poor Design Space Policy". There are substantial weaknesses in the policy capacity of the LHCs as analyzed under the matrix model of policy capacity, which defines political capacity as a set of skills, competencies, resources and institutional arrangements and capabilities with which the key tasks and functions in the political process are structured, staffed and supported. Considering these weaknesses, together with the history of the process of formulation of the Councils and the set of complex tools available to them, it is possible to say that LHC is more a design than a non-design-based formulation process. As a result, we can identify a space of formulation only partially informed marked by a restricted design space to promote real social changes.