This study aims at assessing the extent to which the Ethiopian policies are based on rational policy analysis. Explanatory analysis methods are used to analyze primary and secondary qualitative data. The finding shows that in the policy making process only one policy option was investigated and crafted; the criteria used to evaluate the proposal are not clear; sophisticated solution methods haven’t been used. Though there were many consultations with stakeholders, they couldn’t be sources of many policy options due to their objective, timing and poor citizen’s political culture. Moreover, the study found out that there is lack of technical capacity and advice at the center of the government, the parliament and line ministries. Thus, government needs to do the following; establish advisory institutions, consultations should be done before crafting a draft, policy criteria should be identified, and solution methods should be used in selecting the best policy.

Public policies are any intentional decisions of a government. A policy is a statement by government of what it intends to do or not to do, such as a law, regulation, ruling, decision, or order, or a combination of these (Birkland, 2001). Public policies are inevitable in any form of government as policies are instruments for governmental actions without which nothing could be done. Governments go through public policy making process to make their policies. The policy making process is a cyclical process from the problem identification, agenda setting, policy formulation and the policy enactment (policy implementation and policy evaluation) (Howlett and Rahmesh, 2003). Every government makes policies; though the detailed issues in the process may depend on the type of government.

In democratic governments, public policies are any government actions taken on behalf of the public because the public has given the government the legitimacy to act through social contracts. A policy is what the government acting on our behalf, chooses to do or not to do (Dye, 2005). Thus, democratic governments are responsible to adopt policies that satisfy the interest of the public and that can solve public problems. Advancing the quality of public policies is a key stepping-stone which contributes to level of trust the public may have on its government (Shepherd et al., 2010).

To make policies to the best interest of the public and capable of solving public problem, governments should base their decisions on scientific policy analysis of the problem situation and potential solutions. Dunn (2004) has defined policy analysis as a process of multidisciplinary inquiry designed to create, critically assess and communicate information that is useful in understanding and improving policies. Policy analysis helps policy makers by providing important policy relevant information such as defining the problem, identifying potential policy alternatives that can solve the problem already defined and recommending the best policy alternative based on some predetermined criteria. Linder and Peters (1988) have noted the significant role of policy analysis in effective policy making by saying: “Understanding how policy alternatives are generated and elaborated upon is fundamental in order to produce better policies.” However, the extent to which the policy making practices of countries are based on systematic policy analysis is a question needed to be raised.

Researches conducted on the Ethiopian policy making process and specially policy analysis are scanty. Some researchers have studied the policy making practices in the country (Dereje, 2012; Cloete and Abeb, 2011); practices and challenges of the Ethiopian house of peoples‟ representatives and its role of oversight (Tiruye, 2015; Awel, 2011); and few studies are done on the actors, roles and leverage of the policy making process in the country (Mulugeta, 2005). According to Mulugeta (2005) the policy making process is dominated by the ruling party and it is un-participatory in which limited number of actors are involved. Those identified actors are the three branches of government especially the legislative and the executive as well as politically affiliated associations. But the general public, civil society as well as other interest group‟s role is very limited.

In addition, according to Halderman (2004) the contemporary policymaking and implementation in Ethiopia is strongly influenced by a long history of centralized, hierarchical system of controls under imperial rule and nearly two decades of military rule by the Derg. Likewise, Cloete and Abebe (2011) have also indicated the influence of the past on the existing governmental decisions and put it as: The legacy of the Derge seems to weigh heavily upon policy making and administration in the contemporary Ethiopia.

Moreover, Dereje (2012) has revealed that the top-down approach to policy making is the frequent practice of the incumbent government of Ethiopia at different levels. This signifies that the policy making process revolves around the branches of government and few dominant interest groups. In other words, the effort to get policy initiatives and policy proposals from the grass root public is minimal. Furthermore, Cloete and Abebe (2006), in their article argued that in the Ethiopia policy making process policy elites are playing significant and exclusive role starting from agenda setting up to policy implementation.

In addition to the closed and elitist approach policy making in the country, some researchers have also found out that the executive branch of the government has dominated the policy making process and the role of the legislative is becoming insignificant. For instance, Tiruye (2015) has succinctly puts it as: almost all the laws/ policies passed by parliament have originated from the executive, and the legislatures were engaged in reviewing and approving legislation.

However, these researchers have not covered the issue of policy analysis in their studies. The researcher believes that even if there is domination of the executive branch of the government in the policy making process and the process is highly elitist in nature, it is imperative to investigate how polices are formulated. Thus, this research aims at assessing the practice of policy analysis as a base for policy formulation focusing on the child policy, youth policy and National Social Protection Policy (NSPP).

Rational public policy analysis

Policy formulation is a critical pre-decision phase in the policy process that aims at identifying best solution for a problem. Policy formulation involves assessing possible solutions to policy problems or, exploring the various options available for addressing a problem (Howlett and Ramsesh, 2003).

Ex-ante policy analysis is an integral part of policy formulation since policies are formulated based on the policy relevant information obtained by undertaking policy analysis. In other words policy analysis is subsumed in the policy formulation phase of the policy making process. The process of defining, identifying, accepting and rejecting policy options is the substance of the policy formulation phase (Howlett and Ramsesh, 2003).

Policy analysis helps policy makers to make informed policy decisions. Interest groups and researchers use policy relevant information to strengthen their policy ideas and arguments with policy makers.

According to Dunn (2015), policy relevant information is drawn from the following major issues; nature of the problem at hand, the possible alternatives that can solve the problem, the outcomes of each alternative, which make sure that the outcomes, contribute to solve the problem as well as the expected outcomes if other options are chosen.

In policy analysis knowledge is not an end result, but utilizing knowledge to solve a problem is the objective. Hajer (2003) has explained the problem solving nature of policy analysis as: “The commitment (of policy analysis) to a problem-orientation implies that knowledge is not to be pursued as a goal in itself, but to help resolve particular societal problems”.

The significant role of policy analysis is not only constrained in solving specific identified problems using best solutions but also saves a nation from social, economic and political crises beforehand. The result of systematic policy analysis saves the nation and the citizenry from uncalled-for some exogenous shocks or what is preferably termed as policy earthquakes (Dunn, 2015).

Though it has been argued that policy analysis is not practical and used as an input for policy making in many countries , it is important to consider the process as a flexible process as per the political and other different contexts of a country. The necessity for scientific policy analysis can‟t be underestimated in solving public problems (Roux, 2002).

Steps in rational policy analysis

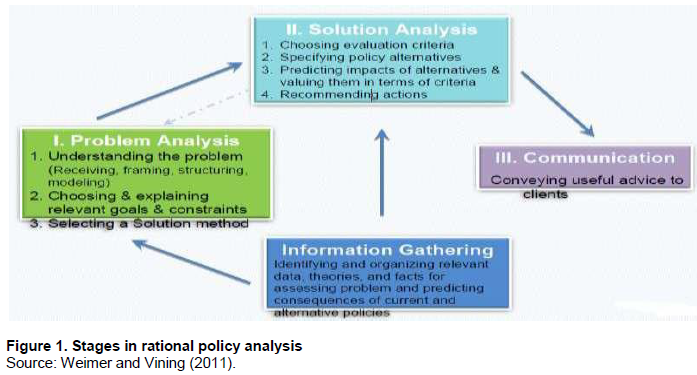

Weimer and Vining (2011) have classified policy analysis in to two major components which are problem analysis and solution analysis and the result of these two components will be communicated to the client. It should highly involve information gathering without which analysis is impossible. Policy analysis has the potential for creating sound policies and at the same time requires information gathering and communication (Dunn, 2015).

As it is depicted in Figure 1, the rationalist policy analysis starts by analyzing the problem. Any individual may be able to identify a public problem that needs to be solved through government intervention but it is mostly difficult to define a given problem by identifying its causes.

The whole public or the clients perceive problems as undesirable conditions and worries. Thus, they tend to specify problems in terms of undesirable symptoms or impacts rather than clearly articulating the cause. Thus, the analysts‟ task here is to assess the symptoms and provide an explanation of the causes of the problem and describe the severity of the same. Moreover, the analyst has to explain the problem in terms of market failure or government failure (Weimer and Vining, 2011).

In addition to this the analysts has to link causes and consequences of the problem in a conceptual model. Conceptual model shows the relationships between the conditions of concern/consequences to variables/causes that can be manipulated by public policy.

The analyst also makes a list of the goals/criteria and explains each briefly that are the values he/she wants to promote by means of the policies that he/she will recommend to his/her client. The criteria are vital values while comparing different potential policy options; hence, the analyst secures value to each option based on their contribution to each value. Weimer and Vining (2011) have classified criteria into two; substantive (such as efficiency and equity) and instrumental criteria (such as political feasibility administrative and technical feasibility). The critical point that makes policy analysis rational is its nature of identifying different potential policy alternatives. In order to secure different policy alternatives, Roux (2002) recommends that analysts should painstakingly search for different views, ensure that they are not prejudging an alternative and keep all hypotheses open to question. According to Oberg et al. (2015), from a democratic perspective, reducing the number of policy options to just one at the early stage of policy formulation is problematical for at least three reasons. Firstly, having only one policy option may affect legitimacy of the policy. Taking several options into account in decision making, is an indicator of the participation of different group of societies, individuals and interest groups, in other words the decision making incorporates the will of the people. Secondly, proposing only one option decrease the likelihood that final decisions as well as choices will be based on fact and logic. Thirdly, democratic accountability cannot be clearly seen by the public if only one option is proposed and selected, it would be difficult to evaluate their efforts to choose best option because they don‟t have answer for questions such as; what options were not selected, what were their expected consequences, and why were they not chosen?

Moreover, Dahida and Maidoki, (2013) succinctly argued that the key feature of a policy is that it involves a choice; it is an important choice or a critical or major decision taken by individuals, groups or organizations. This means that there has to be several policy alternatives. In addition to the significant role of identifying different policy options, evaluating those using appropriate criteria and choosing the best one is imperative (Meltsner, 1972; Dror, 1969; Howlett and Rahmesh, 2003).

Policy analysis should be undertaken by identifying different options through examining divergent views and weighing the advantage and disadvantage of each, then selecting the best one. Ponge (2013) also clearly stated this idea as: “A policy recommendation will need to be based on a systematic enumeration and weighing of all potential benefits and costs of an intervention if it is to be credible”.

Cochran and Malone (1996), assert that policy formulation or policy analysis deals with the problem, goals and priorities, policy options to achieve objectives of the policy, undertakes cost benefit analysis to estimate the costs and benefits of each option as well as identifies the potential negative and positive externalities associated with each alternative.

Moreover, policy analysts should do the solution analysis and identify what solution method may particularly be used. The nature and number of goals/criteria largely determine the appropriate solution method analysts are supposed to choose. The commonly used solution methods are cost benefit analysis (either qualitative or quantitative), modified cost benefit analysis, cost effectiveness analysis and multi-goal analysis (Weimer and Vining, 2011).

In summary, a policy analysis is rational if it opts for identifying all the possible policy alternatives, forecasting their consequences, setting criteria for evaluating the alternatives and recommending the best solution based on the prescribed criteria. Analysts have to look in detail at what causes what while dealing with policy options for predicting the consequences of policy alternatives is an integral element of policy analysis (Bardach, 2011). Policy analysis practices may differ from country to country. However, according to Fishery et al. (2007), we can examine the practices of policy analysis of countries by determining: The criteria set to evaluate the appropriateness of policy analysis and roles of policy analysts; the methods of policy analysis adopted; the institutionalization as well as institutions involved in policy analysis.

In this study descriptive and explanatory research methods were used. Descriptive method was employed as the research aimed at describing the practice of using policy analysis results as foundations for policy making, in detail but as it is. In addition, explanatory method was used because it helps to answer questions like who formulated the policies, how and why.

For this particular study a pure qualitative method was found to be appropriate as there are only few informed individuals about the issue and the study requires in-depth information on the subject under investigation.

Owing to this, the informed individuals had to be selected purposively to secure exhaustive information and subjective opinion from those key informants about the practice of policy analysis of the child policy, youth policy and NSPP. The researcher selected these policies purposively because they are the most recent national policies.

Primary and secondary data were used in this study. Primary data was collected from the ministry of labor and social affairs (MoLSA), ministry of women, youth and child affairs (MoWYC), Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (FDRE) policy research and study center, forum for social studies (FSS) and the house of Peoples‟ representatives (HoPRs) regarding the steps gone through to formulate the policies.

In addition to primary data, the researcher has reviewed relevant documents to corroborate the primary data and to secure data regarding the policy advice sources. The documents reviewed are the 1995 constitution, the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia rules, procedures and members‟ code of conduct regulation No.3/2006, Council of Ministers (CoMs) working procedure, 2003, report of the taskforce for formulating child policy, and report of the platform for national social protection of the consultations held with stake holders.

The research employed interviews, focus group discussion and open-ended questionnaire to collect the primary data from the aforementioned sources. Open-ended questionnaire was used because it was found to be appropriate to gather supplementary facts as it helps to come up with detailed opinions of the respondents.

To get reliable and relevant information the researcher has selected respondents which have been directly involved in the formulation of NSPP, youth policy and child policy from MoLSA - 7 respondents and MoWYCA - 7 respondents, from the FDRE policy research and study center - 5 respondents, HoPRS - 3 respondents and FSS researchers - 3 respondents who had experience in policy analysis have been contacted and selected. And finally a member of the HoPRs has been contacted and interviewed.

Then finally, owing to the qualitative nature of the study, content analyses were used dominantly to analyze the data collected.

Policy analysis in the formulation of the three policies

The members of the national platform who were assigned to design the NSPP and the taskforces which were assigned to design the child policy and the youth policy have reported that the policy formulation process starts after the CoMs accepted the request from the respective line ministry.

Soon after the line ministry formed taskforces in the case of youth policy and child policy and a national platform in the case of the NSPP. The respondents indicated that the major responsibility of the taskforces and the platform is producing a draft policy document.

Regarding the composition of the members of the taskforces, in case of the child policy and youth policy, the whole activity of the taskforces were undertaken by the employed experts of the MoWCYA. But the national platform for social protection was assisted by non- governmental consultants and scholars in undertaking research and crafting the draft policy in addition to experts and higher officials from the MoLSA and Ministry of Agriculture.

The ad-hoc taskforces started policy formulation by undertaking researches which are gap assessment in the case of NSPP and youth policy to find out the gaps and weakness of the previous policies so that the gaps can be addressed in the new policy, and needs assessment in the case of child policy to clearly spell out the needs of the public, particularly, the target group that the government believed has to be satisfied. The assessments done can be considered as parts of problem identification, though the respondents have indicated that there is lack of policy expertise and as a result the quality of the researches were not as desired. After the assessments are finalized, a draft policy was crafted by using results of different researches and best practices of other countries as an input.

Subsequently different consultative forums at federal and regional levels are organized to create a sense of ownership within the stakeholders, which the government believes is helpful for effective implementation and is a critical venue for gathering and compiling various opinions and views of stakeholders and partners. The respondents have reported that in addition to the consultations with the federal and local government institutions, there were many and exhaustive forums with nongovernmental organizations, different associations and the social affairs standing committee of the parliament. Then after, based on the comments of the stakeholders the taskforces improve and made amendments on the draft and forwarded the bill to the CoMs.

Policy criteria and solution methods used

According to Weimer and Vining (2011) policy analysts should make a list of the goals/criteria that they want to achieve by means of the policies that they will recommend to their client. Weimer and Vining (2011) argue that policy options should be compared based on some criteria. The common ones are; efficiency, effectiveness, equity, political feasibility, and administrative operability.

A question was posed to the respondents to account for the policy criteria used in formulating social protection policy, youth policy and child policy and almost all of the respondents and coordinators of the platform and the taskforces failed to clearly understand what policy criteria are and to this end they are held in reserve from answering.

Contrary to this, the advisor to the minister of MoLSA has revealed that they have tried to check the estimated financial capacity of the government and the required fund during implementation. In other words, as could be understood from the preceding responses, though they lack the knowledge regarding to the meaning of policy criteria they have used efficiency as a criteria. But he indicated that to evaluate the efficiency of the policy, they have not used sophisticated methods of analysis such as cost-benefit analysis (CBA) or cost effectiveness analysis due to lack of organized data source and multi-sector coordination. He added and said that there was a research done regarding the costs and benefits of the policy by university scholars but they have not utilized it because they were not comfortable with it.

Ignoring scientific analysis methods and just trying to say we are safe financially without exploring and monetizing at least the major costs as well as benefits and focusing on the aggregate financial capacity of the country doesn‟t help capture the policy implementation a long way. The actual practice seems to be kind of “trial and error”.

This implies that there is lack of technical expertise not only in operating but also in utilizing and understanding those methods within the ministry. This is in harmony with the conclusion of Shepherd et al. (2010) that infers developing countries are weak in advancing technically sound policy process.

According to Weimer and Vining (2011), in addition to other criteria, administrative feasibility of policies should be evaluated in the way to select the best one. They indicated that it refers to the commitment and support of top managers and the whole staff of the agency responsible to implement the policy and the resources available in terms of staff, skills, money, training, expertise.

The results of the interview held with a researcher from FRDE policy research and study center give some discussion points related to the criteria issue. He asserts that the problem in Ethiopia regarding the policy formulation is in administrating and implementing the policies, and puts his idea as: “we have smart policies in any standard but flawed implementation.”

The view of the interviewee is not new to be raised. Many Ethiopians use to say the same. But can we categorize the policy package into two parts by saying policy and implementation as if they are not connected at all?

Many scholars have indicated that while designing or formulating policies the implementation element should be there (Birkland, 2001; Howlett and Rahmesh, 2003; weimer and vining, 2011). This means policy implementation is a single element in the policy package; which can‟t be separated and talked about only. In other words, while designing policies, the strategies the bureaucracy will use to implement, the capacity of the bureaucracy and the commitment and support of the civil servant should be studied vigorously. And that‟s why we need to have an administrative feasibility criterion to evaluate. Therefore, the researcher argues that the implementation problems are most likely the defects of the policy analysis, despite the fact that analysts are not completely perfect in predicting conditions, and as a result some external factors may hinder policy implementation. In accordance with this, Linder and Peters (1988) referring different research results, assert that policy design affects the implementation and outcome of political decisions.

To sum up, the survey indicates that though the government has tried to assess the capacity of the bureaucracy and the resources required to implement the policies, profound and strong study in the administrative feasibilities of policies (such as commitment and support of the bureaucracy) through consultation before adopting the policies is lacking. This problem is causing defective implementation as well as a disconnection between policy analysis and implementation.

Alternative policy options investigated

According to Weimer and Vining (2011) specifying different policy options is an important part of rational policy analysis. Trying to take different policy alternatives into consideration to choose the best one is crucial because while trying to compare different options the negative and positive consequences of each, the costs and benefits of each as well as different views of stakeholders towards the options should be incorporated in the way of choosing the best one. Thus, the process will be rational, justifiable and logical since we can‟t have one best thing without comparing it with something else.

According to Öberg et al. (2015), analysts should not limit the number of alternative to just one at the early stage because this may damage the legitimacy of the policy option, the decision may lack logical reasoning and the decision makers may lose their accountability because they have no justification to the decision they made.

The researcher trying to mark whether the policy analysis processes in Ethiopia particularly of the NSPP, youth policy and child policy incorporated many policy options or not, have posed questions to the respondents in the MoLSA and MoWYCA. Respondents from MoLSA, have responded that there was only one option and similarly the coordinators of the national social protection platform responded that it was only one, but interestingly tried to give justifications saying: “Why other options? It is just obvious that this is the best option. We have tried to see many country‟s experiences that have promising achievements in formulating and implementing social protection policy based on the African Union framework such as South Africa, Kenya, Ghana, India and Brazil and we have seen that it is best for our county too.”

Öberg et al. (2015) have revealed that such a type of reasons for not proposing many policy options may be indicators of an instrumental bias - a bias on a specific perspective. In this regard, it seems that the United Nation‟s declaration of social protection as an element of human rights and African Union‟s pressure over its member states to incorporate social protection in their policies and strategies has influenced the Ethiopian government to come up with the NSPP with a total focus on the predetermined lines. In spite of the fact that any country cannot live isolated in a globalization era and it is inevitable that there is policy learning and transfer among countries and international institutions. However being in the circle of the framework that the countries have signed, rational and systematic considerations of many options could be done which has a paramount importance in the quality of policies the formulators may come up with.

Regarding to the child policy, the respondents from MoWCYA, members of the taskforce which was responsible to craft and formulate the policy have indicated that there was only one policy option investigated but only one of the members has said that there was another option raised claiming that we don‟t need to have child policy as it has been incorporated as one element of the NSPP. But it can‟t be considered as a second policy option since it was discarded at the very early stage of the process. The respondents in the MoWCYA task force for youth policy also hold the same view that there was only one policy proposal under investigation and consultation and it was finally presented for approval.

Öberg et al. (2015) have asserted that having only one option at the early stage of policy formulation can be an indicator of lack of stakeholder‟s participation. Concerning the three selected policies it will be noteworthy to see the level of public participation during the process to look over the reason behind the „only one policy option‟. To answer this, the researcher has raised questions to the respondents regarding the participants involved and the level of policy consultations held.

Respondents from the MoLSA have indicated that there were many consultations with national and regional government‟s public officials, with the society particularly the target groups such as old aged people and disabled citizens through their associations, the social affairs standing committee of the house of peoples‟ representatives, different related ministries, scholars from Addis Ababa university as well as nongovernmental and international institutions such as IGAD, UNICEF, ILO, UN Agencies.

Similarly respondents from the MoWCYA have indicated that to formulate child policy they have had consultations with children themselves particularly vulnerable ones, with the society in different national government institutions and all regional governments and city administrations concerned bureau officials, governmental and nongovernmental institutions working on children related issues such as all ministries who have concern on the issue, the HoPRs specially the social affairs standing committee, African child policy forum, forum for social studies, ANPPCAN, UNICEF, ILO, Save the Children, Adoption agency network, OVC Network and different religious institutions. Moreover, they said that even consultations and dialogues with stakeholders were one of highly considered as well as performed issues while crafting the policy.

Regarding youth policy, the respondents from the same ministry have responded that youth associations, state/regional governments and city administrations concerned bureau officials and experts and UN agencies had involvement in the process as stakeholders.

Moreover, all the respondents have confidently indicated how hard they have worked on including the society‟s opinion on the formulation process by saying: “One of the strong things we have done is consultation with many stakeholders and we can say we were successful.”

In addition to the responses of the respondents, different reports of the aforementioned ministries concerning the process also signify that consultations with the above-mentioned stakeholders were held.

To sum up, the data secured by the researcher show that many consultations were apparent during the formulation of the three selected policies but it has been seen that these consultations couldn‟t be sources of other options. At this juncture, two points can be raised as impediments that make those consultations not to be sources of different policy alternatives:

Firstly, the objectives of the consultations were to create awareness and to include views of stakeholders on the already initiated policies. Owing to this the consultations were held after the policy is crafted. Thus, participants are expected to raise either questions or additional points that they thought can improve the policies. This shows that the government or the formulators of the policy have not tried to just put the problem as it is and allow stakeholders particularly interest groups, think tanks and academics to come up with potential policy options.

Secondly, it seems that the political culture of citizens has influenced their capacity and confidence of proposing policy options. For instance, awareness or orientation towards either the political system or the citizen as a political participant and his/her influence on public policies formulation have impact on the effectiveness of their participation and presentation of different competing policy alternatives that can solve the problem at hand. This was also supported by Dereje (2012) that particularly the state governments and local governments have been seen to be poor in practicing their policy mandates that the 1995 constitution has vested on them to formulate their own policies within their own jurisdictions that could be one source of innovative policy options for the federal government. In addition to this, Ugumanim et al. (2014) have declared that the low level of literacy of the masses in developing countries is a reason that public opinion seldom influences the policy- making process.

Suffice it to say, therefore, the process to secure different policy options that enable the platform and the taskforce members to have several alternatives to be evaluated, compared and analyzed and then presented to the decision makers was very poor.

Sources of policy advice and technical expertise

Governments can have different sources of policy advice such as government affiliated research institutions, non- governmental research institutions and consulting firms. But, in this study it has been referred to only governmental research institutions which work exclusively for the government for three main reasons.

Firstly, in Ethiopia the utilizations of policy advice from non-governmental and independent research institutions are limited (Abate and Selamawit, 2015). In addition to other factors what Stone et al. (2005) contends seems to be the reason that decision makers demand more research findings that can legitimate their policy decisions. Secondly, exclusive research institutions are supposed to be trusted sources of policy advice for government as a result, the findings of these institutions are directly utilized for policy decisions. Thirdly, institutions other than the exclusive government research institutions do not conduct research solely for particular policy consumption.

Sources of advice and technical expertise in the line ministries

Proclamation No. 691/2010 has empowered each ministry to initiate or formulate laws and policies and as a result, the policy making process is centered in the line ministries. Starting from policy initiation to policy formulation it has been found out in this study that the line ministries are playing a crucial role and it is inevitable that in order to perform those major policy making roles they need technical expertise. Thus, in a bid to discover the level of technical expertise the respondents were inquired if there is any specialized policy unit or center in their ministries.

As a result it has been found out that in the MoWYCA there is no any unit/office established for the purpose of initiating or formulating policies and no autonomous policy advisory institution working exclusively for the ministry. They added that when a need comes to formulate policy their ministry forms an ad-hoc task force or technical committee whose members are the employed experts and directorate coordinators to craft a draft policy. The same was done in the case of child policy and youth policy. The ministry has used its own employees to formulate the two policies which is not a problem by itself but these experts are engaged in policy analysis without special expertise in the same and along with their day to day activities as a result they may lack time and technical expertise in using sophisticated and systematic analysis methods.

On the contrary respondents from the MoLSA have indicated that there is a program and policy unit within the ministry which is mandated to initiate and formulate policies with in the substantive responsibility of the ministry. Another question was posed to them to account for the capacity and level of expertise of this center through interview and open-ended questionnaire.

The result of the interview with the coordinator of the policy and program unit points out that the unit is new and it is difficult to evaluate its effectiveness, but it is evident that there is lack of experts and specialists in public policy. Contrary to the response of the coordinator of the unit, the director of the social welfare development promotion directorate contends that the number and level of expertise of the employees they have under the unit is quite adequate to accomplish its substantive mandate and responsibility.

Despite of the two contradictory responses of the officials, observations of the researcher as well as empirical evidences indicated that there is immense gap in technical expertise within this unit, three evidences can be mentioned.

Firstly, if there is a strong policy unit within the ministry it is expected that the process of policy formulation of the NSPP would be laid on the shoulder of the unit, but this was not the case. What the ministry has done was forming an ad-hoc platform comprising of employees of the ministry, employees of other relevant ministries, scholars and consultants.

Secondly, the national platform was assisted by non- governmental consultants particularly in undertaking relevant research. It should be under question mark if any ministry would opt for hiring consultants having a strong policy advisory unit. Government institutions would hire consultants if their own personnel failed to produce the desired level of analysis or their employees lack the required expertise.

Thirdly, in the previous sections of this chapter it has been found out that the constrained number of policy options presented and analyzed, the lack of interest and technical capacity of using sophisticated solution methods clearly show the gap in technical expertise within the government and particularly the line ministries.

Suffice it to say, therefore despite of the existence of the unit, it is poor technically in undertaking systematic policy analysis. Likewise, Abate and Selamawit (2015) have revealed that the researches done by experts employed in government institutions particularly line ministries are poor in quality.

It has been observed in this study that line ministries which are on the direct supervision of the CoMs had dominant role in initiating the policies as well as formulating the same, despite of the fact that regional bureaus, other governmental agencies and the parliament had contributed information and comments as stakeholders. As a result, crafting the policy drafts were laid on the hands of the respective ministries and a long process was gone through to formulate the policies after the CoMs permits to go forward.

However, the process of policy analysis process gone through to formulate the three policies has been noticed to be rationally and scientifically weak despite the strong and exhaustive efforts from the side of the government to make the policy making process participatory. There are some situations which are reasons for the weaknesses aforementioned. Firstly, only one policy option for each policy was specified and investigated, however, due to the timing and objective of the consultations and dialogues held, the participation of stakeholders couldn‟t create deviating influences over the polices. In other words, because consultations are held with stakeholders after a first draft is already crafted and as a result stakeholders are only expected to give their comments on the proposed policy option, the dialogues have failed to be sources of many policy options. Secondly, the policy criteria used were not clearly designated, though implicitly there are indications that efficiency and administrative feasibility were used partially. But, to evaluate the efficiency level, no appropriate solution analysis methods were used and regarding to administrative feasibility no emphasis was given to evaluate the support and commitment of the bureaucrats. In addition to this, this study has revealed that the line ministries lack advisory institutions or units or departments working exclusively for them which can be considered as one reason for weak technical analytical capacities within the government.

Based on the data secured and the analysis made, the following recommendations or way outs are forwarded:

Policy consultations and dialogues should be undertaken before a policy proposal is designed. After policy formulating committees gather information and investigated different views from stakeholders, scholars and researchers, it has to come up with man policy options from which the best one is to be selected. In addition to this the objective of the consultations should not be to create awareness or collect comments on the already proposed policy but the government should allow stakeholders to make difference by keeping all assumptions and views of stakeholders open to questioning, searching assertively for divergent views that can be included in its decisions and avoiding prejudices in favor of a particular proposal.

The committees/policy formulators should analyze various policy alternatives with regard to the negative and positive consequences of each, the benefit and cost of each as well as the score of each as per the criteria already specified, and then present them in written briefings and made available to decision makers so that they can make informed decisions.

To make the policy analysis scientific enough, policy criteria that the government need to promote through the policy should be clearly specified and based on the number and nature of the criteria, sophisticated solution methods should be selected and used to evaluate each policy alternative and choose the best one. are strong enough to initiate policies and to use scientific and rational methods of policy analysis regardless of any political affiliation. Recruiting policy experts and analysts for this purpose can be one way to strengthen their capacity.