ABSTRACT

This study attempts to develop a pro-poor health care financing system for Eritrea. The study seeks to answer the following question: can the rich and healthy subsidize the poor and sick in Eritrea? This question is directly related to issues of social insurance and universal coverage. This study was conducted in 2016 in six months period from February to August. In this study, both primary and secondary data sources were used. Interviews were conducted with 35 key health officials and stakeholders. In this study, it is found that lack of purchasing power and financial resources; insufficient knowledge of health insurance schemes and high transaction costs; and lack of supply and information about care possibilities are the main problems for the development of a viable healthcare financing system in Eritrea. As the Ministry of Health is embarking on new pricing and cost recovery strategies, a closer look of its effects on consumers is required, particularly on the poor and vulnerable groups. Significant increases in revenues from user fees increases may not be realistic, given the country’s high poverty rate. The health care financing policy needs to be assessed in light of current and projected health sector needs.

Key words: Eritrea, health care financing, Sub-Saharan Africa, health policy, health insurance.

Eritrea is a country located in the Horn of Africa region bordered by the Red Sea to the east, Djibouti to the southeast, Ethiopia to the south, and the Sudan to the north and west. Eritrea gained independence from Ethiopia in 1993 after 30 years of armed struggle. With a population of about four million people, Eritrea has an area of 124,320 Sq Km.

The country’s economy is largely dominated by subsistence agriculture. About 80% of the Eritrean people depend on farming and herding for its livelihood and almost 70% of the people live in countryside. The population density ranges from 36.3 to 40.6 people per sq. km (World Bank, 2002). Eritrea is a low income country; for the year 2010 the gross domestic product (GDP) for Eritrea was estimated at US$3.625 billion together with a per capita estimate of US$681 (Desta, 2013). Despite its income, Eritrea has registered significant progress in child and maternal health. Eritrea is one of the few African countries that have achieved the Millennium Development Goals of 4, 5, 6 and 7.

Health is an integral part of the national development program in Eritrea. In its poverty reduction strategy (2001 to 2002) and macro-policy (1994), the Government of the State of Eritrea (GoSE) clearly stated that health is the key input for national development. The country has six health regions (Anseba, Debub, Southern Red Sea, Gash Barka, Maekel and Northern Red Sea) and 54 health districts (Kirigia et al., 2012).

The health infrastructure comprises 369 health facilities, including 13 tertiary hospitals, 13 secondary hospitals and 343 primary level facilities (health centres, health stations, Maternal and Child Health units and Clinics, clinics and health posts) (GoSE, 2010a).

Health services are provided in Eritrea in three hierarchical levels: primary, secondary and tertiary. On the top there are teaching and national referral hospitals, in the middle regional referral and district hospitals and at the bottom primary health care facilities. Primary health services are very broad and comprehensive, and the facilities provide many community health services such as immunization, mother and childcare, health promotion (information, education and communication) and other preventive and curative services.

Primary health care facilities serve also as an entry points for curative services. There are also 292 licensed private pharmaceutical institutions, including 33 pharmacies, 31 drug shops and 228 rural drug vendors (GoSE, 2010b). The secondary and tertiary levels provide mainly curative services. Secondary level health care facilities encompass zone and sub-zone referral and first contact hospitals respectively. The national referral hospitals constitute the tertiary level health care facilities. The health infrastructure is operated by 215 physicians, 2505 nursing and midwifery personnel, 16 dentistry personnel, 107 pharmaceutical personnel, and 88 environment and public health workers (WHO, 2011).

The GoSE is in the process of forming national health policy rather than reforming as many countries are doing. For Eritrea the establishment of a comprehensive national health system, which is equitable, accessible and affordable for the poor, is a top priority.

This study, therefore, attempts to develop a pro-poor health care financing system for Eritrea that ensures contributions to the costs of healthcare are in proportion to different household’s ability to pay, and protects the poor from the financial shocks associated with severe illness by enhancing accessibility and quality of services.The main concern in health care financing system in Eritrea is that “can the rich and healthy subsidize the poor and sick”? This question is directly related to issues of social insurance and universal coverage, which is quite challenging for developing countries like Eritrea. Hence, the study adopts a deductive approach to explaining the healthcare financing systems in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Review of health care financing system in Sub-Saharan Africa

The reality in many Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) countries is that health service systems are not providing cost-effective services in ways that would have the greatest impact on the major causes of illness and death. One of the problems in the public health system is that health service providers rarely receive incentives and there are no stipulations for service quality and quantity; no measurement of effectiveness and productivity.

Chronic shortage of drugs, infrequent equipment maintenance, inadequate logistical support, and weak supervision further contribute to inefficiency in health service (World Bank, 1994a). The rising costs, limited funding and increasing inefficiency have greatly weakened the ability of SSA countries public health systems to provide effective care and universal coverage (Shaw and Martha, 1995).

Consequently, many SSA countries rely on donor’s finance. In 1990, for example, Burkina Faso covered 71% of its health expenditure by aid, and Sierra Leon and Tanzania covered 50 and 51% of their health expenditure respectively. In Lesotho, donor financing covered about 80% of the Ministry of Health capital budget between 1987 and 1992 and in Uganda donors financed 87% of total public development expenditures on health in 1988 to 1989 (World Bank 1994a: 152). Foreign aid covers 20% of the total health expenditure in SSA.

With the decline of donors financing and sharp fall in tax revenues many countries in SSA introduced private out-of-pocket payments. Out-of-pocket payments include user fees at public sector facilities as well as direct payments to private providers, ranging from doctors working in private practice to informal drug sellers and traditional healers. In many countries user fees cover about 43% of the total healthcare expenditure (World Bank, 1994a).

Private-for-profit and private voluntary clinics, including church/missions charge fees for their service to recover costs and to sustain their services. Since 1991, the Central African Republic, for example, has adopted four different user fee schemes: a charge for services rendered; a flat charge for each episode of illness; a flat fee per visit; and prepayment for a year of service (ECA, 2003). A study conducted in Zaire, in the Bwananda District, further showed that, between 1986 and 1988, user fees accounted for 109 to 111 per cent of the operating costs of the health centers (World Bank, 1996).

In Bwamanda hospital, between 1986 and 1988, about 30% of the operating expenses were covered by user fees. The user fees were then supplemented by insurance payments and employer billings, which accounted for 22 to 33% and 13 to 22% of operating costs, respectively. At tertiary level, healthcare facilities revenues generated from cost-sharing ranged between 59 and 75% of total operating costs between 1986 and 1988 (World Bank, 1996). Four mission hospitals, in Uganda, recovered 78 to 95% of their operating costs, and nine of eighteen non-governmental dispensaries, in Tanzania, recovered 100% of their operating costs from user fees, and seven of twenty-one NGO hospitals recovered more than 75% of their operating costs (Shaw and Martha, 1995).

User fees are a stimulus to self-financing health insurance schemes. Shaw and Martha (1995) contended that SSA countries should impose user fees first in government healthcare facilities, especially at hospitals, before jumping into self-financing health insurance schemes. The reason is simply that when public health services are provided for free or at low cost, people are less likely to pay for insurance premiums to cover unexpected health hazards.The argument is that user fees can enhance more efficient, equitable and sustainable use of health care services. By charging fees for curative/personal healthcare services at tertiary level healthcare facilities, governments can free up and reallocate budgets to public health services (for example, community health services, immunizations, and control of infectious diseases).

Matji et al. (1995) however, warn that charging for health care without improving the quality of service is disappointing, as it has been seeing in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Clients must feel that they are getting value for services that are no longer provided for free. The issue of quality must be addressed before the implementation of user fees. User fee should also be accompanied by appropriate waiver mechanisms. There are growing international evidence that user fees can push households down into poverty if appropriate waiver mechanisms are not in place (Whitehead et al., 2001).

The world health organization (WHO) has estimated that 100 million people become impoverished by paying for health care each year and that a further 150 million face severe financial hardship from health care costs (WHO, 2005). Direct cost sharing through user fees does limit access, especially by those who are most prone to the consequence of ill health and those in low-income groups (Stewart, 1999). The introduction or increase of user fees in the public health system may create inequalities in access to services, particularly where compulsory exemption systems do not exist or provide inadequate safety nets for the poor (Segall et al., 2000; Ensor, 1995; Wilkinson 1999; World Bank 1999).

Even exemption mechanisms are in operation, inequalities may be exacerbated also by ineffective targeting, as well as significant administrative, economic and informational barriers to their implementation (Russell and Gilson, 1997). In low-income countries, the demand reduction effect of user fees is the source of much concern than the demand diversion effect of user fees. After the imposition of user fees, in most SSA countries, the demand for government healthcare facilities diverted to non-government facilities including a shift to informal medical care and home remedies.

Sauerborn et al. (1996) noted that one of the first strategies of coping with the costs of illness is to try to avoid these costs altogether by modifying illness perception or ignoring disease. The poor often delay seeking care until an illness is severe, which may ultimately lead to higher costs of treatment. Patients consult traditional healers or use traditional medicines available at home, or purchased from a drug seller at a relatively lower cost than at public facilities, are another frequent strategy for avoiding or at least minimizing costs (McIntyre et al., 2005; Save the Children, 2005).

To cover rising healthcare cost, households use also coping strategies such as reducing consumption, selling assets and borrowing (McIntyre et al., 2005). Russell and Abdella (2002) in their study in Ethiopia found that households used available cash to pay for health care and sale assets such as livestock and land, which are essential to their future livelihood.

In many SSA countries, there are complaints that the improvement in quality is below expectation when it is compared with corresponding increase in user fees. Moreover, very little attention has been paid to the design and implementation of effective exemption mechanisms.

Few countries in Sub-Sahara Africa (SSA) have a viable health insurance system; existing social insurance schemes, in most SSA countries, cover a negligible portion of the population. Griffin and Shaw (1995) noted that the total population insured in SSA countries ranged from .0.01% in Ethiopia to a high 11.4% in Kenya. A survey conducted by the World Bank further revels that in 39 SSA countries it was found that 14 countries have formal insurance systems in place and another 4 countries have some kind of employer provided program, 18 have no formal system (Nolan and Turbant, 1993). Vogel (1990) characterized the prevailing government health insurance arrangements in Sub-Saharan Africa as follows:

1. Health care is financed, for all citizens, out of national revenue and provided for free at point of use, as in Tanzania;

2. Health care is financed both by general tax fund and through cost recovery mechanisms and provided by government, as in Ghana;

3. Health care is financed through the enforcement of compulsory Social Security system for the entire formal labour market, as in Senegal;

4. A special health insurance fund for government employees, as in Sudan;

5. A discount at health care facilities for government employees; as in Ethiopia;

6. Government employees are entitled to private medical care as fringe benefits, as in Kenya; and

7. Employers are mandated to cover the health care costs of their employees, as in Democratic Republic of Congo.

In most SSA countries, public health centers and hospitals tends to be funded, by the government, based on historic budgets due to this in most public health facilities there are little accountability and built-in incentive systems for health workers and managers to boost efficiency gains in health service production (Bitran and Winnie 1998). Furthermore, in most public health facilities healthcare is provided free of charge, to improve equity and access, partly limiting the right of patients to demand timely and good quality healthcare service. Hence, in SSA countries free care and the associated inability to collect revenue from patients, has limited the ability of health workers’ and managers to improve output levels, quality and input mix.

Many countries in African are undergoing public service reforms. These reforms were initiated by the quest for efficient and effective public service provision influenced by structural adjustment programs and new public management movements of the 1980’s.

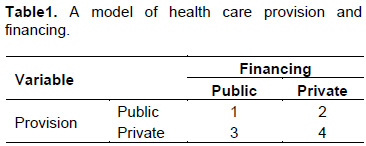

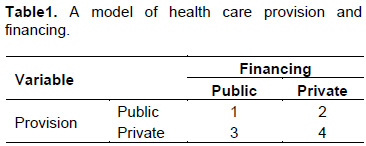

Most of the reforms involve restructuring of government institutions, the creation of new systems, procedures, and functions that are expected to promote efficiency and responsiveness. Similarly, the reforms in healthcare revolve around four health care provision and financing mechanisms (Table 1). These are: public provision and public financing (Cell 1); private financing and public provision (Cell 2); public financing and private provision (Cell 3); andprivate provision and private financing (Cell 4).

Cell 1 is a pure model of the welfare state where the state directly provides as well as finances (through taxes and other public funds) health care services free at the point of use. In this system financing and provision of health services are government responsibility (e.g. Nordic countries traditionally). The public sector has generally taken on responsibility for the delivery of services and frequently used civil service bureaucracies as the instrument. The state owns all the relevant assets, and resources are allocated through instructions given to agents through a managerial hierarchy. Classic examples are, of course, the systems of economic organization that characterized the Soviet Union and Eastern European countries before the fall of the Berlin wall. Le Grand (1999) described the system as “command and control” or “hierarchical” system. At best, this system supplies good quality care at reasonable cost according to clinical need. However, usually there are waiting lists and it seems to encourage an impersonal style of service. At worst, it results in crowded and low quality services, supplied by ill-motivated staff in shabby premises. Patients often corrupt the professionals by private "under the table" payments (Soeters, 1997).

In cell 1 health workers receive salaries and patient has no choice of provider. This means that the incentives for providers are perverse. Efficient providers may receive as ‘reward’ more work but not more resources and the ‘reward’ for the inefficient providers may be quite life and idle resource (ibid.). In a broader way, cell 1 can be used for pure public goods such as security, street lighting, refuse collection, ground and road maintenance, local economic development in residential areas, and infectious disease control.

Tax-based financing was the principal form of health care financing in most of SSA, South Asia and former Soviet Union and much of Eastern Europe countries. There are four solid arguments for tax based public provision and public financing of healthcare services:

1. In mature economies, tax-based systems tends to be progressive, that is, households with higher incomes pay a higher proportion of their income in tax)

2. The poor are protected from large healthcare costs

3. Pure tax-based financing systems have high financial accessibility because they do not involve user fees at point of use; and

4. In low income countries, the revenue generating potential of user fees is low, due to this the scope for improving the quality and accessibility of rural primary care services is limited.

These arguments, however, challenged particularly in the situation of low and middle income countries on five grounds:

1. Tax financing system shifts the locus of decision- making from the consumers to the government, limits consumers choice and sovereignty

2. Tax-financed healthcare services are skewed towards subsidizing urban hospital services at the expense of the rural poor and primary healthcare services

3. Tax-financed healthcare services cannot be truly accessible, particularly to the poor, due to significant time and transport costs

4. In tax-financed healthcare services, even though there are no formal charges, healthcare services cannot be widely accessible to the poor due to the prevalence of informal charges; and

5. In many developing countries, transitional economies tax-based financing systems are constrained by limited tax bases, because of that a small share of the total government budget is allocated to health services.

In cell 2, healthcare services are financed by user-fees and other sources of private finance but now they are provided by the state. Cell 2 is potentially unstable if user-fees are completely financing health care costs and payments are indeed voluntary. In this case there is less justification for the provision of health care services by the public sector. In such situation economists recommend privatization, which will result a shift from cell 2 to cell 4. Activities will only remain in cell 2 if healthcare is in joint supply with other activities in cell 1 and if their separation is technically not possible or incurs extremely high cost or a decision is taken by the public sector provider to continue to make public supply available beside private sector provision.

The impact of user fees on the poor has been subject to more argument and discussion than any of the other financing mechanisms discussed here. Albeit these arguments, the introduction of user fees in a tax financed healthcare systems has been proposed to be pro-poor for two main reasons:

1. The introduction of user fees in urban hospital services would channel subsidies to the rural poor; and

2. User fees increase resources available for healthcare and would allow governments to expand or upgrade their network of rural, primary healthcare services to make them accessible to the rural poor.

In cell 3, public financing is combined with a private delivery of services. This system is common in Canada, Japan, parts of French and Germany (Donaldson et al., 1993).

Health services are contracted out to private healthcare service providers. In this system horizontal integration of the population is achieved through universal coverage of public financing. Compared to cell 1, in this system the population has more options for the choice of providers. There are also more opportunities for autonomy, and competition among providers. In this system there is a global public budget, just like in the public system (cell 1).

In cell 3, the role of the state is changed to more of a regulator rather than universal provider and it can.be referred to two cases. First, the state makes transfer payments to individuals by means of which they can get health care services from private providers. Second, health care services are contracted out to private providers. The first essentially improves allocative efficiency since purchases reflect individual wants and willingness to pay. The second, however, does not improve allocative efficiency since decisions regarding the quantity and quality of healthcare services remain within the public domain. In this case consumers are not sovereign.

In cell 4, healthcare is financed and provided by the private sector. It is a mandating welfare state whereby the state passes legislation for mandatory health insurance coverage. This system is applied in USA where citizens are entitled to have their own health insurance coverage from private health insurance markets but there are exceptions in the case of Medicare and Medicaid, both programs are funded by the state under social insurance.

In USA, healthcare services are provided by both public and private sector, and the system is characterized by pluralism, free choice and competition. Rich countries, like USA, have changed the organization of the healthcare financing system from bilateral exchange between consumers and providers, where the consumer pay the provider fully and directly for services to trilateral exchange by introducing a formal financing organization to pool the financial risks.

Cell 4 is hardly successful in low income countries. In these countries, private insurance market tends to be limited. It is confined to politicized groups and elites, majority of the people do not have the ability to pay for private health insurance even with the existence of liberal regulatory environment. But there are some important exceptions in micro-insurance schemes, which were recently implemented in Burkina Faso, Benin, Ghana, Cameroon, Mali, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Nigeria, Tanzania, Senegal, Togo, and Uganda (Denis and Johannes, 2005).

In countries such as Zimbabwe and South Africa, there are gross disparities between income groups, higher income groups tend to depend upon private health insurance. Consequently, a move to cell 4 would be progressively self-reinforcing. The political voice for more spending within the public sector can be weaken if more people are making their own insured provision of private health care. The result could be that private sector provision of the service becomes more attractive, making public sector provision residualized. In such a case the shift from welfarian to post-welfarian increases, the so called overspill model of privatization.

Post-welfarism contains elements of cell 2, 3 and 4, whereas welfare is represented only by cell 1. Consumer sovereignty would be facilitated more by a cell ¾ hybrids, user-charges being imposed at less than full cost hence publicly financed, partial subsidies continue in conjunction with competition for consumers between alternative providers.

The shift from welfarism to post-welfarism has several threads, and it can be thought as a continuum rather than as distinct categorical shift. The query is whether the shift reaches a border short of complete post-welfarism. That depends upon the nature of individual services, parti-cularly private healthcare service provision, whether it is complementary with or substitutes for public provision. For example, for the private sector healthcare provision, it can be argued that it would not be profitable to treat all medical conditions, particularly the chronically sick and terminally–ill, in this case the shift will reach a natural limit.

The shift from welfarism to post-wefarism can also be encouraged if the informal sector of the economy takes on a growing absolute and relative responsibility for such provision to ease restraints on government expenditure. For example, provision of residential care places by local government for the elderly can be limited by fiscal stress. Usually, this happens when there is a structural gap between revenue collection and expenditure pattern of the government; consequently, government would have difficulties to finance the rising costs of public service provision with available revenue. To fill this gap families and local community voluntary organizations will take on more responsibility for care of the elderly, to cope up with an aging demographic structure. Governments encourage such moves by tax reliefs and other fiscal incentives that would lead to a progressive shift from cell 1 (or cell 3) to cell 4 in Figure 1, as demonetization and/or re-domestication of service provision takes place.

This study was conducted in 2016 during a six months period from February to August. In the data collection process, senior Public Administration students of the College of Business and Economics were involved. The students were advised to conduct research on health care financing in SSA with special emphasis on Eritrea, as part of their senior research project. In this study both survey and case study methodologies were used.

The case study and survey methods are not mutually exclusive; hence, one could have a case study within a survey or a survey complementing a case study (Hakim, 1987; Dancey and Reidy, 1999). The study adopted descriptive and explanatory case study methods in the analysis of health care financing in Eritrea.

The case study method has an advantage of using multiple sources and techniques in the data collection process, for example; documents, interviews and observations. Survey is the appropriate mode of enquiry for making inference about large groups of people based on the sample drawn, relatively small number of individuals, from that group (Marshal and Rossman, 1995). Further, surveys provide rapid and inexpensive means of determining facts about people’s knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, expectations, behaviours, etc.

Primary and secondary data were collected for the survey and case study design. Primary data was collected through interviews and observations. Interviews were conducted with 35 key government officials and development partners (10 MOH officials, 10 physicians, 5 officials from development partners (donors), and 10 local government officials). To check, the reliability of data and information gathering respondents were asked similar questions at different times.

Secondary data was collected from the archives of the MOH (documents, publications, and annual reports); reports of the World Bank, international monetary fund (IMF), WHO, United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP); and reports of Eritrea’s Demographic and Health Surveys.

Thus, the secondary data was collected from various sources inter alias relevant books and journals, international and national health reports, published and unpublished documents.This study is the first of its kind in Eritrea. So far there is no much research on health care financing in Eritrea and in most SSA countries country specific studies are lacking.

This study, therefore, fills the gap and paves the way for further research on health care financing in developing countries.

Through an interview and observation, the study investi-gates the key challenges and opportunities, provider payment mechanisms and revenue collection systems of Eritrea’s healthcare system. It reviews also the existing health care financing policy of the GoSE. The key challenges identified include shortage of skilled human and financial resources, non existence of insurance markets and insufficient knowledge of insurance scheme, and poor referral mechanisms.

The opportunities include high government commitment, community participation, existence of good health care infrastructure, introduction of cost sharing systems and willingness to pay for quality health care services. The provider payment mechanisms include line item budget, global budget, fee for service, case based payment, capitation, per diem, and salary.The study assesses also different revenue collection systems, such as tax funded national health system, user fees, tax funds plus social health insurance, cost sharing plus tax funded, community health insurance and private health insurance.

Review of existing healthcare financing policies of the GoSE

Eritrea’s national health policy intends to ensure equity and accessibility to essential services at an affordable cost for majority of the population, in accordance with the Universal Health Coverage principle. Maternal and child health issues got high priority in the national health policy with an intension to meet MDG targets and beyond. Attention is also given to communicable and non- communicable diseases, as well as strengthening health system components. The health care financing policy of the GoSE, therefore, emphasizes on:

1. Service specific exemption policy: Service specific exemption to certain illnesses or services. These are antenatal services, well baby services, immunization, leprosy, tuberculosis, mental illness, sexual transmitted diseases (STDs), human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS), emergency cases for first 24 h, injuries from explosives and health education. In addition, those who can obtain a certificate of indigenous from the local MOLG office will receive free care. The cost of their care, however, will have to be paid by the local government, which issued the certificate.

2. Non-discretionary exemption policy: The GoSE uses none-discretionary exemption criteria such as gender, age, region, and type of service, as they are less likely to affect access of the poor to health services. The discretionary criteria, such as income and physical assets are difficult and costly to administer in Eritrea.

3. Income specific exemption policy: Waiving user fees for the poor, who possesses indigent certificates. Indigence certification has specific requirements:

a. An applicant for the indigence certificate should be a resident of the zone/sub-zone at least for the previous six months and should not earn a monthly income of approximately more than 500 Nakfa (at local exchange rate US$ 33.33). In rural areas a person/household with no ox for farming would be considered eligible for indigence certificate.

b. The applicant’s claim of indigence has to be confirmed by a testimony of three individuals who are residents of the particular sub-zone (area administration).

c. Effective from the date of issuance, the waiver certificate is valid for three months.

Health officials stated that the MOH has nothing to do with the issuance of indigent certificates; it is the responsibility of the local government. In the new proposed health care financing policy, it is clearly stated that local governments are responsible for health care costs of all the patients who are duly certified by them as indigent.

4. Credit schemes: For non-indigent citizens (formal and informal sector employees) care is provided on credit basis. In patients pay a deposit of 500 Nakfa when they are admitted into the hospital. On discharge from the hospital, they settle the bill. In cases of shortfall, they are made to pay the difference, and if the deposit is greater than the actual bill, they get a refund. For people obtaining care with a “sick report”, the bill is sent to the respective employing organization. The employer deducts the fee from the salary of the individual and sends it directly to the central treasury. The hospital is notified of the payments made to the treasury office by a letter from the employer.

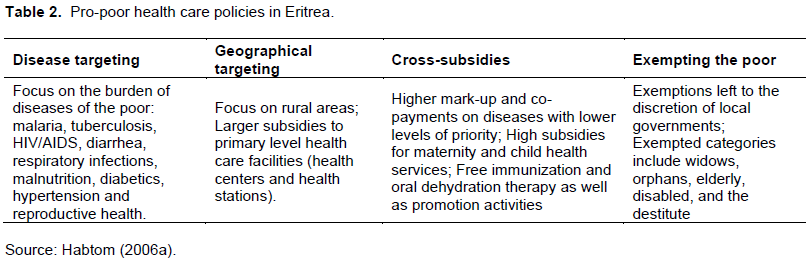

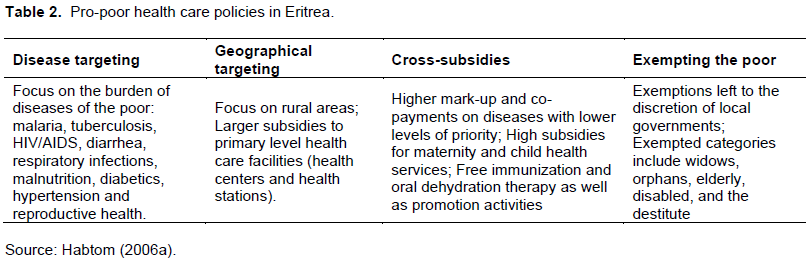

5. Pro-poor health care policies: A question was asked to public health officials, in the MOH, if other policy instruments are available to help the poor in Eritrea besides the waiver mechanisms. The director of public health service stated that there are many pro-poor primary health care programs in Eritrea; HAMSET project is one of them. HAMSET project focuses on the prevention of four diseases (HIV/AIDS, Malaria, Sexually Transmitted Diseases and Tuberculosis). There are also other programs like expanded programs of immunization, health education, and family planning. Pro-poor health care policies, in Eritrea, include cross-subsidization of basic health packages, selective intervention (disease targeting), geographical targeting (focus on rural areas), and exemptions for the poor. Table 2 illustrates the pro-poor policies of the government of Eritrea. Cross-subsidization of basic health packages for the poor is an important health policy in Eritrea. In a situation of limited financial resources, it is important to base the allocation of public health funds to cost-effective programs. About 54% of the respondents replied that basic health packages for the poor are moderately subsidized, and 31% replied that they are highly subsidized. Officials in the MOH explained that basic health packages for mothers and children (for example, immunization, delivery, antenatal and postnatal care etc.), and for the poor and elderly are highly subsidized. This is in line to the World Bank argument that poor countries must target their resources to the poor so that they can obtain some meaningful health care (World Bank, 1994b). 6. Efforts towards universal health coverage: According to the universal public system, everybody should get all the care he/she need, when he/she need it, on equal terms and conditions, without financial barriers. But this is a statement of principle; in practice healthcare services are rationed according to relative need or according to ability to pay. In Eritrea, the drive for equity in healthcare provision calls for universal coverage, with care provided according to need rather than according to ability to pay. In principle, no one should be left out, no matter how poor or how far they are. In a situation where all cannot be served, those most in need should have priority. Here lies the “all” in the health for all mantra. In Eritrea, this is the basis for planning health services for defined populations, and for determining different needs in all administrative regions.

Assessment of revenue collection systems

The prevalence of a high burden of disease in Eritrea challenges the public health system both in financing and provision. The GoSE is looking for alternative sources of finance for health care. Free health care policy failed to warrant service quality and long-term sustainability.

In due course, the GoSE introduced user fees to support the strained public health facilities. Revenue collection through user fees (cost-sharing) was supported by 30% of the respondents, tax funded national health services by 50%) and social health insurance by 20%. Most respondents argued that user fees rationalize the use of resource by freeing up highly expensive technology and personnel for more complex referred cases. The management of less costly services at health centers would make easy the task of combating preventable diseases and hospitals would not be squandered on easily detectable and treated illness. Equity could also be served by introducing progressive user fees. A combination of cost recovery systems (general taxation, social insurance, private health insurance and limited out of pocket user charges) may be preferred to ensure financial sustainability of the public health system in Eritrea. However, cost sharing would be successful only if it led to immediate and measurable improvements in access and quality of health services.

Currently, in Eritrea, at the level of health station and health center, the flat rate charges are inclusive of registration and consultation, treatment and where available, of laboratory services at the health center level. A one-time payment entitles the client to a free care for a month regardless of the episode of illness. The registration and consultation fees are lower at regional and sub-regional hospitals than at national referral hospitals (tertiary hospitals).

In hospitals, fees are levied for procedures (operation, delivery etc.), investigations (laboratory, X-ray etc.), and drugs besides to registration and consultation fees. Fees for laboratory and x-ray services did not include labour and capital costs (depreciation of equipment and building). The fees were set on the basis of costs of consumable items such as chemicals reagents, films etc. The way fees are set made a difference to their acceptability. In some contexts, people have shown that they are more prepared to pay for drugs and dressing than for ‘registration fees’. Drugs and dressings account for a relatively high proportion of health expenditure in Eritrea (about 28% from 1994 expenditure data). They are thus an attractive basis for a cost recovery policy.

Health insurance (social and private) is another possible source of finance for the public health system in Eritrea. The plan for the introduction of national health insurance was clearly specified in the government’s macro-policy, which was issued in 1994. Despite the government’s policy 63% of the respondents stated that no bold action has yet been taken for the introduction of social insurance scheme whereas 37% replied that there are some government concerns for the introduction of social insurance some time in the future. Public health officials, in the MOH, underscored the importance of social insurance in the health sector and maintained that the government’s intention is still towards that direction. As 70% of the Eritrean people live in rural areas and depend for their livelihood on subsistence agriculture social insurance will be applied only to urban dwellers who are employed in formal sector jobs.

The development of efficient private health insurance system, in the short-run, is highly unlikely in Eritrea. The lack of supply and purchasing power are the main problems. Insurance cannot be created without a healthcare market. The private health sector is under-developed in Eritrea. Unlike in advanced economies private health insurance markets in Eritrea may face also problems of adverse selection and moral hazard. In private health sector neither the doctors nor patients may have any incentive to economize on treatment, and insurance companies may face difficulty in distinguishing between good and bad risk individuals.

Assessment of provider payment mechanisms

Although there is no single optimal method for paying providers, three provider payment mechanisms were selected by most respondents. These were line-item budgets (40%), global (lump sum) budget (70%) and retrospective fixed fees per case or per inpatient day (28%).

The method of payment of providers has an effect on access, efficiency and quality. For example, hospitals and physicians, under the fee-for service, have an incentive to deliver more units of service with little regard to medical need. If payment to hospital is based on actual number of beds occupied, they have an incentive for increasing the patients’ length of stay per admission; to keep their beds fully occupied. Hence, all methods have some advantages as well as disadvantages, and the desirability of a specific approach depend upon the social, economic and institutional context of a particular setting.

Most respondents stated that mixed forms of provider payment mechanisms are superior to reliance on any single method because they are more practical and allow a tradeoff of administrative costs and desirable incentives. Different payment mechanisms can be combined to foster the provision of some form of treatment while providing other services in a more restrictive way (for example, fee-for-service plus basic salary for preventive and health promotion services).

The payment to hospitals can also be a combination of prospective budget, a fee for service, or a charge per day, per admission, or per diagnosis-related group. A fee for service, capitation, or salary system can be used to pay physicians in a combined or single form depending on the working conditions.

In low-income countries like Eritrea, complex fee-for-service or case-based reimbursement schemes are not appropriate (Barnum et al., 1993). Fee-for-service and case payments are not the best way to reimburse for the public health and primary services appropriate to the epidemiological environment (high rate of communicable diseases, high fertility, and high infant mortality) in most poor countries (ibid.).

The schemes require also greater degree of resources and training. With proper quality monitoring, prepaid caption schemes or straight global budget can have an important role in low-income countries. For middle income countries with more developed institutions that are partly through the epidemiological transition, the benefits of relatively simple service based or case-based reimbursement-especially in the institutional context of competitive provision of services--begin to outweigh the administrative costs of the systems.

Key challenges of Eritrea’s healthcare system

Shortage of financial resource

About 70% of the respondents stated that shortage of financial resources is the major challenges of the Eritrean healthcare system. Most health facilities in Eritrea are reported to be experiencing a shortage of funds (World Bank, 2003). The user fees collected are not sufficient enough to recover recurrent costs, and none of the revenues collected are retained at the health facilities. The respondents further noted that there is uneven distribution of financial resources between preventive and curative health services. About two-third of the recurrent budget is consumed by hospitals, which provide mostly curative services. Primary level health care facilities have shortages of financial resources. In Eritrea about 90% of the recurrent health expenditure is spent on curative health services. The amount of funds allocated to community and preventive services was not adequate, which was 1.3 and 18%, respectively (Shaw, 1999). This was not in line to (primary health care) PHC policy, which advocates for private financing of tertiary health care services and public financing for public health and essential clinical service packages.

Shortage of skilled human resource

In Eritrea, there is huge gap between the demand for and supply of health personnel. The human resource gap, in the Eritrean health sector, can be explained by the following two factors:

1. Since independence, the GoSE rapidly expand health infrastructure to cater national health needs has led to a high demand for health personnel; and

2. The increase of non-communicable diseases combined with the burden of communicable diseases demand a higher level of skilled personnel to provide specialized services.

In essence, the current issue is not only numbers but also competency and the right mix of the health professionals that are able to respond to current, emerging or re-emerging health conditions in Eritrea. About 75% of the respondents stated that shortage of qualified medical personnel, in the short-run, can be addressed by three ways:

1. Active recruitment of health personnel from urban to suburb/rural areas with adequate pay, benefits and other incentives.

2. Recruitment of expatriate staff from Far East or other developing countries; and

3. Staff substitution.

According to the MOH annual activity health report in 2002, about 27% of the physicians, 3.4% of the nurses and 5.9% of the associate nurses are working in administrative areas. Physicians in hospitals commonly perform management functions that could be more effectively and cheaply filled by trained managers who are not physicians.

High burden of disease

The prevalence of a high burden of disease in Eritrea challenges the public health system both in financing and provision. Preventable diseases are still responsible for about 70% of the burden of diseases in Eritrea. Communicable and nutritional deficiency diseases such as diarrhoea, acute respiratory infections, tuberculosis, malaria, HIV/AIDS, skin and parasitic infections are the major health problems facing the poor in Eritrea. In 2002, these diseases were responsible for 60% of outpatient, 40% of inpatient incidences and 56% of inpatient deaths. About 65% of the respondents stated that the free health care policy in Eritrea will not warrant service quality and long-term sustainability as long as there is high burden of diseases in the country. As documented by the WHO, developing countries bear 93% of the world’s disease burden, yet merely account for 18% of world income and 11% of global health spending (Denis and Johannes, 2005).

Limited health insurance coverage

Health insurance in Eritrea is currently restricted to compulsory work-related accidents insurance for employees in companies of 100 or more, and a very small number of health cover supplements to private accidents and injury policies. The National Insurance Corporation’s (NICE) mandate is a commercial one. Although the company is considering new products for private health cover, these are likely to appeal to a very small number of people. A social insurance mechanism, with premiums related to income and not to risk, and with cost sharing between employer and employee, is outside the mandate of the NICE. With a formally employed workforce of about 33,000 and no pre-existing social welfare fund, substantial investments are needed to establish comprehensive social health insurance in Eritrea. This financing option should not be considered as a short-term proposition because comprehensive social health insurance is a new concept in Eritrea and it will take time for such schemes to gain acceptance.

Non-existence of insurance markets

Without healthcare, markets insurance cannot be created. In developing countries like Eritrea, insurance involves high transaction costs. In Eritrea, about 69% of the population live below the poverty line (UNCDF, 2001) and about 70% of the population live in rural areas and depend on subsistence agriculture for their livelihood. Eritrea’s large rural and informal sector populations limit the expansion of formal insurance schemes. Health insurance schemes, which intend to cover the rural population and informal sector, will be confronted with low and irregular incomes and high transaction costs. Furthermore, infrastructure, communication and transport networks are minimal (or absent) in most rural and suburb areas in Eritrea. In rural areas there are no banks, no post office or mail services, no roads, and no telecommunication equipment. As a result, transaction costs are high, for example, to collect contributions, file and process claims, register and renew membership, keep members informed, and recruit new members. Griffin and Shaw (1995) identified five causes for high administrative and sales costs for insurance markets in rural areas and in the informal sector economy. These are:

1. Difficulties to identify and insure groups (as opposed to individuals) to minimize adverse selection

2. High transaction costs to collect premiums because lack of a regular income stream or banking system

3. The high cost of credit (which is typically rationed).

4. The high cost of controlling claims in a dispersed population and

5. The lack of reinsurance markets. Development of insurance in less developed countries, especially in rural areas militated by the aforementioned factors.

Insufficient knowledge of health insurance schemes

Many people in Eritrea simply do not understand the concept of health insurance. It takes time to explain the concepts of risk sharing and insurance. The idea of handing over money that will be used to pay for other peoples’ health care is hard to explain-and to absorb. Their main fears are about paying money for nothing, that is, if they are not ill, and paying for others, especially the very poor who are sick more frequently than the better off. Particularly for traditional rural communities, paying money in advance for health care means inviting diseases or bad luck for the family. In rural areas, there is a pervading culture of fatalism that resists cover as a result most rural communities are not used to taking personal responsibility for their health.

Large informal sector and rural populations

Eritrea’s large informal sector and rural populations limit the taxation capacity of the government, which in turn delays the emergence of social insurance schemes with government subsidy. Preker et al. (2004) pointed out that to meet a target of 3% of GDP health expenditure through formal collective health care financing channels, it would take 30% of government revenue and this would be hard if a country’s taxation capacity is below 10% of GDP.

In developing countries like Eritrea, public expenditure on health care is much lower than this, often not surpassing 10% of public expenditure, which means that less than 1% of GDP of public resources is available for the health sector (Preker et al., 2004; Weber, 2004; Diop et al., 1995).

Pooling of financial resources in low-income countries has typical problems. Pooling requires some transfers of resources from healthy to sick, rich to poor, and gainfully employed to inactive (Preker et al., 2004). In low-income countries there is problem of tax evasion, particularly by the rich and middle classes in the informal sector, higher income groups tend to avoid contributing their share to the overall revenue pool (ibid.). Without sharing of risks and pooling of revenues, low-income populations will be exposed to serious financial hardship at times of illness (Diop et al., 1995).

Poor referral systems

In Eritrea hospital entry is a matter of proximity, rather than the appropriateness of the classification, and that most inpatients in upper-level hospitals in most urban areas are admitted directly. Patients often bypass lower level health care facilities and continue to use more costly hospital services for common and mild illnesses. As long as patients believe that health service are better at higher level hospitals bypass fees would have little effect on maintaining the referral system. Many patients said that better services are available only in hospitals; lower level health care facilities do not have adequate staff and diagnostic equipment. A survey in 2005 shows that the main reason for patients bypass of primary level health care facilities was related to service quality: 54% of the patients responded that diagnostic tests at lower level health care facilities are not available, 21% health workers at lower level facilities are incompetent, 15% drugs are not available at lower level facilities, and 10% other reasons (Habtom, 2006a). Overcrowding in referral hospitals and underutilization of lower level health facilities could be partly attributed to lack of adequate staff and services at lower level facilities (MOH, 2001).

Lack of information about care possibilities

The main problem in Eritrea is that even in the absence of user charges, access to healthcare services are not equal due to non-monetary factors such as distance, travel time and lack of information about the possibilities for professional healthcare services (Habtom, 2006a). Lack of resources not only inhibits demand but also people’s awareness about health care services. About 80% of health officials stated that in most rural areas, when people are sick, they look to traditional medical practitioners and traditional recipes, not modern, professional health care institutions. Rural people look for modern healthcare services only as a last recourse. By then, illness is severe, and treatment costs are high.

Disease ignorance

Most of the poor people in Eritrea cope with the rising costs of healthcare services by modifying illness perception or ignoring disease. The poor often delay seeking care until the disease becomes severe, eventually it may lead to higher costs of treatment. Self-treatment using allopathic or traditional medicines available at home, or bought from a drug seller at a relatively cheaper price than at public facilities, are another common strategy for avoiding or at least reducing healthcare costs.

Existing local opportunities for healthcare financing system in Eritrea

Community participation

Community participation is the empowerment of the people to effectively involve themselves in designing policies and programs and creating the structure that serve the interests of all as well as to effectively contribute to the development process and share equitably in its benefits (Habtom, 2016b). One of the key success stories of Eritrea’s development process is its ability to motivate and mobilize communities to participate in the planning, design and utilization of development programs, including those related to health. Community participation is a credo of the GoSE development strategy.

High government commitment

The GoSE Health Sector Policy emphasizes on equitable provision of basic health services to all people, regardless how poor or far they are. The government gives high priority to the control of infectious diseases, especially Tuberculosis, Malaria, HIV/AIDS, and Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STDs), as well as the reduction of maternal mortality. The government focuses also on the improvement of the quality of health services through increased availability and accessibility of human and nonhuman resources.

Existence of good healthcare infrastructure

The GoSE adopted a stratified three-tier national health care delivery system. The system is well coordinated in a hierarchical structure and it is proven to be capable of meeting the needs of the Eritrean communities at all levels. At the bottom of the hierarchy there are primary level healthcare services, which provide basic health care package services. Primary healthcare consists of community-based health services with coverage of an estimated 2,000 to 3,000 people.

The key delivery agent is the community health worker led by the Village Health Committee. In addition health stations offer facility-based primary health care services to a catchment population of approximately 5,000-10,000. Through primary healthcare services the government empowers and mobilizes communities to tackle resources constraints.

At the middle of the hierarchy there are also Community Hospitals, which are the referral facility for the primary health care level of service delivery, serving a community of approximately 50,000-100,000 people. Community hospitals deliver obstetric and general surgical services with the aim of providing vital life-saving surgical, medical and other interventions, in addition to all the services available at lower level facilities,. At the top of the hierarchy there national referral hospitals (tertiary hospitals), which are the referral facility for all regional hospitals.

The MOH estimates that access to health service (within 10 km radius or 2 h walk) has improved from 46% in 1991 to 70% in 1999. Official reports of the MOH further indicated that more than half of the Eritrean population lives within 5 km from a health facility. In line with the expansion of health facilities the respondents were asked about the availability of basic drugs in public health facilities. About 64% of them stated that essential drugs are available; only 36% explained some shortages.

Introduction of cost sharing system

The MOH has been aware at the outset that it could not provide free health service indefinitely. In February 1996, the MOH introduced user fees (registration fees, and daily hotel fees) at all public health facilities. The fees were introduced in order to: provide substantial subsidies for primary care; charge patients the full costs of care at tertiary facilities; and encourage patients to use the referral system appropriately. The user fees were designed in a sliding scale with the highest fee being paid at secondary and tertiary hospitals and lowest at health centers and health stations. Health centers and health stations charge only flat nominal registration fees, which serve for one month. Central and regional hospitals charge patients for investigation, procedures, registration and treatment at a rate close to nominal fee. The low socio-economic status of the population at independence plus the then existing devastated health infrastructure compelled the government to provide health services to the people at a nominal cost or free of charge (MOH, 2001). When health service is provided at free or nominal fees to everybody it typically leads to rationing of expensive services and restriction of choices.

Willingness to pay for quality healthcare services

Fees increase should correspond to quality improve-ments, which means that value for money. It is unfair to ask people to pay, or to pay more, for the same service, they use less of it. The rural poor are more sensitive to price increases than other groups. To keep utilization up to previous levels-or even to increase them- people has to see that their extra payment are being used to improve the service they are getting, for example, extension of opening hours, ensuring availability of basic drugs, medical equipment, etc. Many people will prepare to pay more for their health care if they think that they will get a better care. In the new proposed health care financing policy there are plans to improve the current quality, efficiency and equity levels by 50-60%. There are also plans to decrease clients bypass the referral system by 60%, so that clients will be encouraged to use the preventive health care services and discourage the use of expensive hospital care services for common and mild illnesses.

Designing innovative pro-poor health care financing system in Eritrea

In the developing world health care financing continues to be a challenge despite tremendous government efforts to improve funding of public health services. Many low- and middle-income countries are still far from achieving universal health coverage. Eritrea is not an exception; the health care financing system in Eritrea is often inadequate leaving many poor people without access to the most basic health services.

In Eritrea, government taxation capacity is not strong, formal mechanism of social protection for vulnerable populations are not adequate, and government oversight of the informal health sector is lacking. Public services in rural and low-income urban areas are often plagued by understaffing, supply shortages, and low-quality care due to this the poor and majority of the rural populations frequently seek care from traditional medical practitioners .In most instances the need for collective arrangements and strong government action in health care financing is often confused with public production of services.

Eritrea’s health care financing system is closely associated with the welfare ideology of the government. Health care financing remains the main responsibility of the government. There are no health insurance schemes in Eritrea that facilitate involvement of the private sector. In the absence of health insurance, the government has been striving to finance the health system by leaving resources from households (either in the form of general taxation or user fee).

As government funds are limited health care must compete for its share with many other worthy programs, such as economic development, roads and transportation, communications, and education. Alternative sources of revenue should be sought as the existing budgetary resources are not adequate to finance the public health system. With the existing user fee policy the MOH recovers only 10% of its current expenditure on health care. The fees charged are much lower than the actual cost (MOH, 2001).

The mismatch between current health expenditure and cost recovery, and the growing demand for health care creates a stress in the public health system. Most health facilities in Eritrea are reported to be experiencing a shortage of funds (World Bank, 2003). For example, the Gash-Barka zonal health team in 1997 reported that nearly 65% of the budget allocated for health is consumed by the three hospitals in the region, and even this amount is considered insufficient for efficiently running them.

In 2008, Eritrea’s total per capita health expenditure was US$10; compared to international standards it was very less. About 45% of total health expenditure come from government general expenditure and the remaining 55% coming from private expenditure in the form of household out-of-pocket payments (Kirigia et al., 2012). The external resources for health accounted for 61% of total expenditure on health in 2008; that is channelled through public and private sectors (WHO, 2011).

The degree of interaction between different financing mechanisms would determine the extent to which the financing system as a whole is pro-poor or not. For example, if a tax funded system for those outside of formal sector employment co-exists with a social health insurance system for those people employed in the formal sector, then the equity effects depend largely on how well funded the tax-based system is and whether it can deliver a similar package of benefits to the social health insurance system.

In a situation of limited financial resources, different criteria could be used to allocate investments in health. Policy makers, practitioners and health administrators frequently ration scares financial resources on the basis of one criterion or another. The desirability of alternative financing mechanisms clearly depends upon many factors including ability to generate revenues, administrative efficiency and acceptability to the population. However, it is known that there is no single (or perfect) financing mechanism, either for raising revenue or in allocating expenditure. There are positive and negative to each method, which need to be balanced. In most of the cases a mix of finance is preferable, but the right mix is difficult. For middle-and higher income countries a combination of social insurance, general taxation, private health insurance, and limited out-of-pocket user fees can be the preferred health-financing instruments; where income is easily identifiable, taxes and premiums can also be collected at the source (Preker et al., 2004).

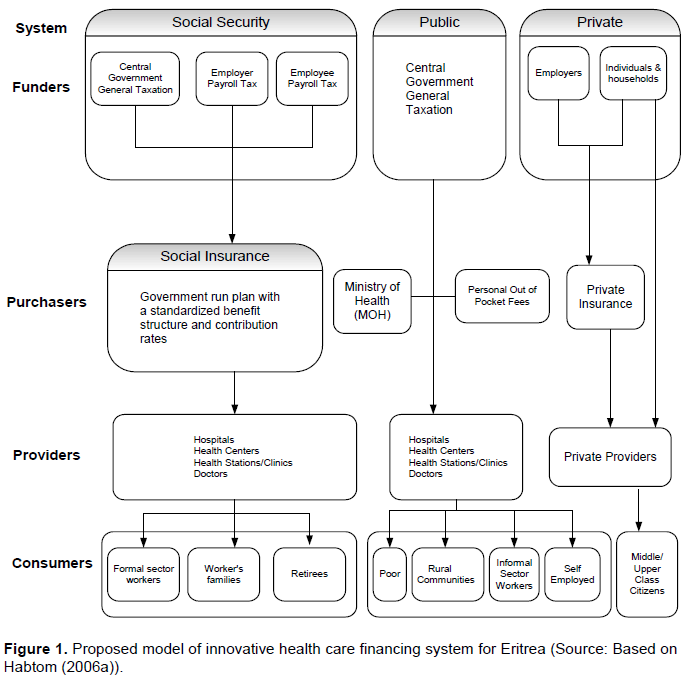

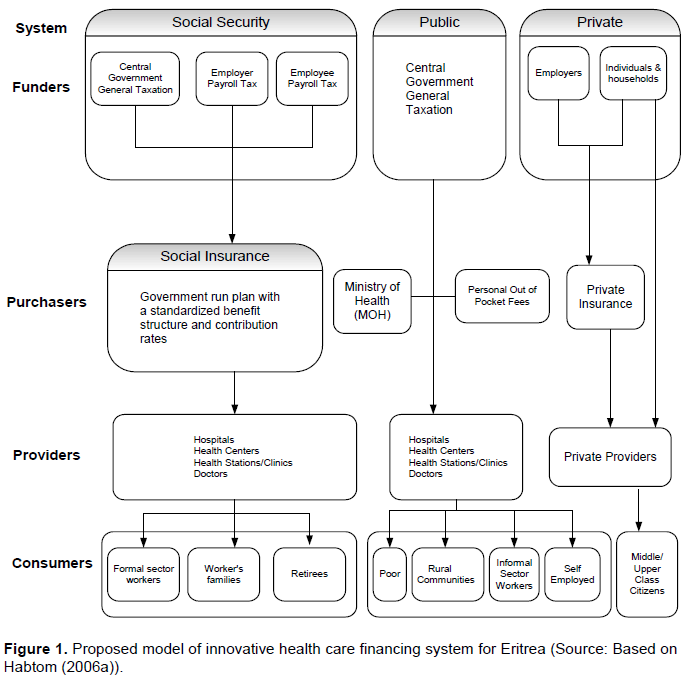

In the social insurance scheme, the public system may cover only certain groups of people, normally those who are in the formal sector jobs (see the proposed mode in Figure 1). Initially social insurance plans can be used to cover health care costs for citizens with regular payments such as civil servants and other salaried employees in formal sector jobs, and later can be extended to the poor and the elderly.

More than 70% of health service providers and almost all health policy makers emphasized the importance of social insurance. In the proposed model social insurance is designed to cover the formal sector workers and better be achieved by a compulsory means. The government-run social insurance scheme will collect premiums from three sources: payroll taxes on employees, payroll taxes on employers, and a contribution from general taxes. Furthermore, to prevent moral hazard and unnecessary treatments, fees will be charged to people with health insurance, which are known as co-payments or deductibles.

But it is obvious that when social insurance coverage is limited to formal sector employees and their families, the poor are going to be excluded because either they are unemployed or are in the informal system. The poor are also excluded if benefits are limited to inpatient care because most of them live in rural areas or periurban slums, far from the public hospitals that are dis-proportionately used by the middle and upper classes. If coverage is universal and benefits are generous, rationing is normally achieved through waiting lists. Again, the poor are discriminated against, because upper-income groups are more effective in bypassing waiting lists. In the proposed model, however, it is assumed that a well developed private health sector in conjunction with public and private health insurance and/or user fees will attract the upper and middle income citizens and eventually public health facilities will be easily accessible to the poor.

As can be seen in Figure 1, public health facilities, which are run by the MOH, will provide health care services to the poor, rural communities, informal sector workers and self-employed people. Public health facilities will be financed through general taxation and user fees. At the same time the government has the responsibility to ensure that the poor is not denied health care; this is compatible with the argument that health care is a“basic fundamental right”.

The main issue in the proposed model of health care financing system in Eritrea is that the government should reduce responsibility for paying for services that provide few benefits for society as a whole and to exempt the government from providing services for the rich. The typical problem with the Eritrean healthcare financing system is that it subsidizes the wealthy who could afford to pay for their own services, and thus leaves fewer government resources for the poor. The policy package for the proposed model of health care financing includes:

1. Introduction of user charges combined with measures to protect the poor from the adverse effects of these costs.

2. Promotion of health insurance schemes to cover cost of medical treatments for an increased proportion of the population. Compulsory coverage of all formal sector workers is proposed together with measures to ensure competition between insurers so that schemes are low cost.

3. Full utilization of non-government resources. Encouragement and incentives should be given to the non-government sector, including missions and non-profit making organization along with private practitioners to provide services for which consumers are willing to pay.

4. Decentralization of planning, budgeting and purchasing to counter internal inefficiency. Introducing market incentives; by allowing collection and retention of user fees at the point of service. Local units providing direct services to people should be given more responsibility in determining how collected funds and money from central government will be spent.

Most officials in the MOH supported the proposed policy package of health care financing system in Eritrea. Health officials in the MOH stated that the local government should have a role in the finance of health care and should cover the health care costs of the poor with indigent medical certificate. About 68% of the respondents supported the idea that local government should retain a portion of the user fees to finance health care costs of the poor and other community health services.

User fees and private insurance schemes can be used to finance private health services.User fees may rationalize the use of resource by freeing up highly expensive technology and personnel for more complex referred cases. The management of less costly services at health centers would make easy the task of combating preventable diseases, and hospitals would not be squandered on easily detectable and treated illness. Equity could also be served by introducing progressive user fees. The introduction of user fees may shift many upper/middle income groups into the private sector and that will make government health facilities easily accessible to the poor at a reasonable cost. At the same time the MOH should enhance its regulatory capacity to make sure that health care service providers are maintaining acceptable quality standards and service procurers (financing organizations) are managing adverse-selection.

In Eritrea, health care services are mainly financed by the government. Social and private insurance systems are not developed in Eritrea. Underdevelopment of health insurance schemes constrains effective public-private mix in health care financing system in Eritrea.

Due to this in Eritrea, health spending overall, and public sector health spending, remains low by international standards. Most health facilities are reported to be experiencing a shortage of funds. The MOH should revise its cost recovery plans of 1996.

In the 1996 pricing policy, fees were designed to provide correct signals for the direction of the use of health care and health sector resources. One of the most commonly cited reasons for imposing user fees were to provide signals that discourage unwarranted use of services that have high cost but comparatively low benefits. However, in practice neither recurrent costs were sufficiently recovered nor patients were discouraged from bypassing primary level health care facilities. Several reports of the MOH indicated that the costs recovered through user fees are not more than 10% on the average. Reports of the MOH on bed occupancy rate showed also overcrowding in national referral hospitals, which is an indication of under utilization of lower level health care facilities.

To overcome the shortcomings of the 1996 health care financing policy, the MOH recently revised its health care financing policy. A new health care financing policy was drafted in 1998, but it has not yet adopted because of the recent border war with Ethiopia. When the draft policy is ratified and becomes operational, the cost recovery of the recurrent expenditure is expected to increase by 40%.

Participation of communities in their own health care service is also expected to increase by 70%. In the proposed health care financing policy emergency cases for the first 24 h, hazardous and contagious disease, and patients with indigent certificates are entitled to get free medical care.

As the MOH is embarking on new pricing and cost recovery strategies, there is a need for a closer look of its effects on consumers, particularly on the poor and vulnerable groups. The health care financing policy should be assessed in light of current and projected health sector needs, together with estimated financing sources and the expected roles of the government, external partners and the private sector, within the context of the country’s high poverty rate, in order to not to lead to a decrease in utilization of services by the poor.

Taking into account the current economic situation in Eritrea, the scope for increasing health fees be restricted to the higher income households. Significant increases in revenues from user fees increases may not be realistic, given the country’s high poverty rate. From a poverty-related perspective, the most worrying aspect of current healthcare financing system in SSA countries is the large share of out-of-pocket payments. Concerns about the negative impact of user fees on equity have been growing throughout the 1990s.

In Eritrea, ways to increase efficiency need to be explored, and priorities in interventions and services assessed and established. To this end, Eritrea should develop a healthcare financing system that can sustain and improve health service delivery to the whole population regardless of patients’ financial status. Hence, the GoSE should focus on:

1. Increasing healthcare financing system by mobilizing more resources into the sector.

2. Restructuring the National Health System in such away that it comprehends community based health insurance schemes to allow better coverage of the grass root population.

3. Developing mechanisms for financial protection, which ensures that all those who need health services are not denied access due to inability to pay and the livelihoods of households’ should not be endangered due to the costs of accessing health care. This indicates that there is a need for the separation of health care financing contributions or payments from service utilization, which requires some form of pre-payment (health insurance or government taxes).

4. Designing progressive healthcare financing system, where those with greater ability-to-pay contribute a higher proportion of their income than those with lower incomes.

5. Promoting cross-subsidies in the overall health system, that is, the healthy subsidizes the ill and the wealthy subsidizes the poor. To this end the government should reduce the fragmentation between and within individual financing mechanisms and develop a system to allow cross-subsidies across all financing mechanisms.

6. Developing a healthcare financing system that promotes universal access to health services. A system whereby all individuals are entitled to benefit from health services via existing financing mechanisms and value for money is guaranteed.

The author has not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Barnum H, Kutzin J (1993). Public Hospitals in Developing Countries: Resource Use, Cost, and Financing. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London.

|

|

|

|

Bitran R, Winnie CY (1998). A Review of Health Care Provider Payment Reform in Selected Countries in Asia and Latin America. "Major Applied Research 2, Working Paper1. Bethesda, MD: Partnership for Health Reform Project, Abt Associates Inc.

|

|

|

|

Dancey C, Reidy J (1999). Statistics without Mathematics for Psychology: Using SPSS for Windows. London: Prentice-Hall.

|

|

|

|

Denis D, Johannes J (2005). Private health insurance for the poor in developing countries? Policy insights, No. 11, OEDC.

|

|

|

|

Desta Y (2013). Applying a US Police Integrity Measurement Tool to the Eritrean Context: Perceptions of Top-Level Eritrean Police Officers Regarding Police Misconduct. J. Organ. Transaction Social Change 10(3):328-261.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Diop F, Yazbeck A, Bitan R (1995). The impact of alternative cost recovery schemes on access and equity in Niger. Health Pol. Plann. 10(3):223-240.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Donaldson C, Gerard K (1993). Economics of Health Care Financing: The Visible Hand, Hampshire: Macmillan Press Ltd.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Ensor T (1995). Introducing Health Insurance in Vietnam. Health Policy Plan, 10(2):154-163.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Government of the State of Eritrea (GoSE) (2010a). Health information systems health facilities report. Asmara: Eritrea Ministry of Health.

|

|

|

|

Government of the State of Eritrea (GoSE) (2010b). Regulatory Health Service. Asmara: Eritrea Ministry of Health.

|

|

|

|

Government of the State of Eritrea (GoSE) (2001). Eritrea Health Profile 2000. Asmara, Eritrea. Ministry of Health.

|

|

|

|

Griffin CC, Shaw PR (1995). Health insurance in Sub-Saharan Africa: Aims, Findings, and Policy Implications. In Shaw, Paul R. and Martha Ainsworth (Eds.) (1995), Financing Health Care in sub-Saharan Africa through User Fees and Insurance, Washington, D.C., World Bank.

|

|

|

|

Habtom G (2006a). Healthcare Governance in Developing Countries: The case of Eritrea. Ph.D. Thesis, Tilburg University.

|

|

|

|

Habtom G (2016b). Foreign Aid Effectiveness and Development Strategies in Eritrea: A Lesson for Sub-Saharan African Countries. J. Afr. Stud. Dev. 8(5):49-66.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Hakim C (1987). Research Design: Strategies and Choices in the Design of Social Research. London: Allen and Unwin.

|

|

|

|

Le Grand J (1999). Financing Health Care. In Feachem, Zuzana, Martine Hensher and Laura Rose (1999) (eds.), Implementing Health sector Reform in Central Asia: Papers from an EDI health policy seminar held in Ashgabot, Turkmenistan, June 1996. The World Bank Washington, D.C.

|

|

|

|

Kirigia J, Eyob Z, James A (2012). National health financing policy in Eritrea: A survey of preliminary considerations. BMC International Healthand Human Rights. 12:16.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Marshal C, Rossman G (1995). Designing Qualitative Research. London: Publications.

|

|

|

|

Matji M (1995). Do user-fee reduce the demand for health care: insights and limitations of service statistics in Lesotho. World Bank Discussion Papers, Africa Technical Department Series 294. Chapter 4. Washington D.C: World Bank.

|

|

|

|

Mcintyre D, Thiede M, Dahlgren G, Whitehead M (2005). What are the economic consequences for household of illness and of paying for health care in lowandmiddle- income country contexts? Social Science and Medicine, In press.

|

|

|

|

Nolan B, Turbant V (1993). Cost recovery in public health services in Sub-Saharan Africa. Washington D.C: Economic Development Institute, World Bank.

|

|

|

|

Preker AS, Jack L, Melitta J (2004). Rich-poor differences in health care financing. In: Dror, David M., & Preker, Alexander S. Social Reinsurance: A new approach to sustainable community health financing. World Bank, Washington, D.C.

|

|

|

|

Russell S, Abdella K (2002). Too poor to be sick: Coping with the costs of illness in East Hararghe, Ethiopia. London, Save the Children.

|

|

|

|

Russell S, Gilson L (1997). User fee policies to promote health service access for the poor: awolf in sheep's clothing? Int. J. Health Serv. 27(2):359-379.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Save The Children (2005). The unbearable cost of illness: Poverty, ill-health and access to healthcare-evidence from Lindi rural district, Tanzania. London, Save the Children.

|

|

|

|