ABSTRACT

The use of banned performance enhancing substances (PES) among athletes continues to be a major challenge in sport. This study evaluated the knowledge of football athletes, coaches and sponsors about doping in Malawi. The specific aspects of knowledge investigated included types of doping substances, sources of information on doping substances, reasons for doping, and consequences of doping on football athletes. The study sought to determine whether there was any association between selected demographic factors (age, level of education and experience) of football athletes, coaches and sponsors and their knowledge of doping in football in Malawi. Data were collected using self-reported questionnaires from football athletes (n=235), coaches (n=24) and sponsors (n=15). Data were analyzed using Chi Square and One Way Variance of Analysis. Results indicated that football athletes (77%), coaches (45.8%) and sponsors (60%) had adequate knowledge of doping. There were significant differences in knowledge of doping substances among athletes (20.76±3.35), coaches (18.54±7.56) and sponsors (21.40±6.95), p = 0.011. The differences in knowledge on doping existed between athletes and coaches (MD = 2.22; p = 0.011) and coaches and sponsors (MD = 2.86; p = .042). There was need for athletes, coaches and sponsors to be engaged in more anti-doping programmes in order for them to acquire more knowledge on doping. Malawi Anti-Doping Organization should establish a website where athletes can obtain information on doping.

Key words: Athlete, coach, doping, knowledge, performance enhancing substances.

Use of banned performance enhancing substances (PES) has negative consequences on health of athletes, sponsorship, leads to unfair competition, constitutes cheating, disrupts social relationships and removes natural altruism of sports (Kaur et al., 2014). Efforts through education, sanctions and tests have been made by international sport bodies such as Football International Federations Associations (FIFA), World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) and International Olympic Committee (IOC) to prevent athletes from doping. Despite this, it is estimated that the global prevalence of doping among athletes in sports is at 1-2%, with football having less than 0.45% (De Hon et al., 2014). In this regard, FIFA contends that there is no systematic doping in soccer (Mottram, 2018). However, Waddington et al. (2005) reported specific cases of former premier league players acknowledging the use of stimulant pills (called pep pills) before matches and emphasized that use of doping was highly organized in Italian football in the 1990s. Giraldi et al. (2015) found that in Italy 6.6% of the males were using substances to enhance sport performance. Morente-Sanchez et al. (2019) found high levels of supplement use among footballers in Spain. In Cameroon, 7% of the participants admitted using cocaine before matches and 16% took alcohol drinks before matches (Ama et al., 2003). Similarly, a meta-analysis of studies on doping in Africa from 1970s to 2013 showed that there was a 2.4% prevalence use of PES by football athletes (Sagoe et al., 2014).

The reasons which prompt football athletes to dope include desire to win, psychological motivation, desired self-image, gaining favors from coaches, social status, improving performance, self-confidence, imitating other athletes, peer pressure and to fulfill contractual conditions by sponsors (Sharman, 2013; Savulescu et al., 2004; Kaur et al., 2014; Muwonge et al., 2015; Barghi et al., 2015; Bae et al., 2017). Anecdotal evidence shows that the need to win competition prompted the Malawian athletes who failed doping controls to use illegal substances (Sharman, 2013). Beyond the knowledge of doping by athletes, it was important to establish the knowledge levels of other athlete support personnel such as coaches and sponsors. This was apt as coaches are significant sources of information on doping and influence athlete’s attitudes either to use or not use illegal substances (Lentillon-Kaestner and Carstairs, 2010).To function as role models, coaches must have adequate knowledge and ethically correct attitudes towards doping (Fung and Young, 2006). This is not remote as coach behavior is often used by athletes to justify doping (Dodge and Robertson, 2009). The role of the coach is even defined by World Anti-Doping Code (WADC) ’…to use their influence on athletes to foster anti-doping attitudes’. This requires coaches to have adequate knowledge on doping in order to prevent athletes from developing pro-doping attitudes (Fung and Young, 2006; Bloodworth et al., 2012). Secondly, enhanced knowledge on doping might prevent athletes from applying doping behavior through the formation of correct attitudes. The goals of the sponsors in football might also determine the conduct of athletes and coaches in doping practices as sponsors may enforce the inclusion of clauses to football sponsorships that emphasize curtailing doping (Atry, 2013).

Studies have shown that socio-demographic factors such as age, sex, type of sport, level of competition and professionalism might influence the prevalence of dietary supplements (Sanchez et al., 2013; Muwonge, et al., 2015; Al Ghobain et al., 2016; Baltazaar –Martin et al., 2019). Therefore it is possible that the above socio-demographic factors will impact the use of illegal substances among athletes. For example, it has been shown that age (Sanchez et al., 2013; Sekulic et al., 2014), education and experience (Muwonge et al., 2015; Kamenju et al., 2016) of athletes and coaches influence their knowledge on doping. Studies have shown that older athletes, coaches and sponsors would have more knowledge on doping as they are mature and have vast experiences related to doping than the younger athletes. For example, Chebet (2014) found out that young athletes in middle and long distance running in Kenya had poor knowledge on doping issues than older athletes and this was attributed to the fact that young athletes were at primary school level of education. At this level of education and age, athletes are not expected to dope but WADA emphasizes value based aspects of clean sport. Similarly, Blank et al. (2015) reported that age of coaches was significantly associated with knowledge on doping in Australia. Therefore, it is probable that older athletes just like old coaches were expected to have more knowledge on doping than young ones.

Studies have shown that the level of education influences knowledge on doping issues. For example, Al Ghobain et al. (2016) found that higher rate of using prohibited substances (doping) among Saudi Arabian soccer players was associated with low education and age below 20 years. It has been reported that experienced athletes and coaches in football related activities in Turkey and Bosnia had more knowledge on doping (Corluka et al., 2011). For example, athlete support personnel who worked more than 15 years among elite sporting athletes in Australia had higher knowledge of doping in sports (Backhouse and Mc Kenna, 2012). This was also the situation in Kenya, where athletes in middle and long distance running with less experience had poor knowledge on doping (Chebet, 2014). Similarly, Blank et al. (2015) found that experience of coaching had a significant association with knowledge on the use of performance enhancing substances. However, experience of participation in sports competition among athletes in teacher training colleges in Kenya did not return any significant difference on knowledge and attitude towards doping (Kamenju et al., 2016).

In 2013, the National Olympic Committee in Malawi facilitated the establishment of the Malawi Anti-Doping Organization (MADO) to fight doping in sports in Malawi (United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2015). MADO like other National Anti-Doping Agencies facilitates testing of athletes for doping and conducts educational programs to sensitize athletes and their entourage on anti-doping. Despite the existence of MADO, there is limited literature on knowledge on doping among athletes in Malawi (Corluka et al, 2011).

Therefore, the findings of this study will assist MADO to initiate and enforce policies that promote doping free sports. Secondly, MADO would be encouraged to enforce doping programs and interventions that involve all stakeholders in sports such as athletes, coaches and sponsors. Specifically, knowledge derived from this study might enable football sponsors to attach anti-doping conditions to their sponsorships.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate knowledge of football athletes, coaches and sponsors on doping substances, sources of information on doping substances, reasons for doping and consequences of doping on football athletes in Malawi. The study also established whether there was association/difference between selected demographic factors of football athletes, coaches and sponsors and their knowledge on doping substances.

Participants and study design

The study used a descriptive cross sectional survey design to collect data on knowledge on doping from football athletes, coaches and sponsors who participated in Football Super League in Malawi. This design was apt as the study was set to collect information from a large number of different categories of respondents. The total number of teams which took part in the super league were 15 and therefore the study targeted 450 athletes (each football club had 30 athletes and 3 coaches), 45 coaches, 15 football club sponsors and 10 football tournament sponsors. From the 15 teams registered in the league 8(53.33%) were based in cities of Lilongwe and Blantyre and took part in the study. These teams were located in the two cities due to the presence of industrial economic activities such as manufacturing, security, entertainment and education (Zulu et al., 2012). From the eight teams which were purposively selected, 240 questionnaires were distributed to the athletes during training sessions but 235 questionnaires were returned representing a return rate of 97.2 % which was considered adequate for the study. For coaches and sponsors the return rate was 100 and 48% respectively. Age of participants ranged from 18 to 36 years with most of the athletes 83 (35.3%) being aged between 25 and 29 years. For coaches, 18 (74.4%) were older than 23 years of age. Most (57.3%) of the participants had Malawi School Certificate Education or secondary education. Participants had varied experiences ranging from 1 to 8 years in playing, coaching and sponsoring football activities with 59.1% of the athletes having played football for 1-7 years.

Study instruments

Data were collected using the self-reported questionnaires adapted from previous studies (Petroczi and Aidman, 2008; Blank et al., 2015; Chebet, 2014). The questionnaire was divided into five sections. Items in Section A were on the demographic details of the participants such as age, level of education and experience. Section B sought information on the list of performance enhancing substances (9 items). Section C had 6 items on the sources of information on doping. Section D had five items on the reasons for doping while section E had four items on consequences of use of performance enhancing substances. All the items were weighted on a likert scale type of YES, NO and NOT SURE. The self-reported questionnaires were validated for content through supervisors at Kenyatta University and adjustments were made where necessary. The questionnaire was administered to 28 participants to ascertain its reliability and test-retest returned a reliability index of 0.90 which was considered adequate for the study. A similar reliability index had been reported in previous studies (Petroczi and Aidman, 2009; Blank et al., 2015).

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was sought from the Kenyatta University Ethical Review Committee in Kenya (PKU/666/1744 OR KU/ERC/APPROVAL/VOL.I.74), Ministry of Labour, Youth, Sports and Manpower Development of Malawi and Football Association of Malawi. Informed consent was obtained from the participants according to established guidelines (Thomas et al., 2011). All participants gave verbal assent and signed written informed consent after reading and getting explanation about the research study. The participants were duly informed that their participation was voluntary, and that their responses will be used for academic purposes and confidentiality will be maintained.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using descriptive analysis of frequencies, means and standard deviations. Inferential statistics of Chi Square test of independent measures and One Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) were used to test for associations/differences based on the participants’ age, education and experience of participants and their knowledge on doping. Significant F ratios were subjected to Tukey Honest Significant Differences (Tukey HSD) to trace the source of significant differences.

Knowledge of athletes, coaches and sponsors on doping

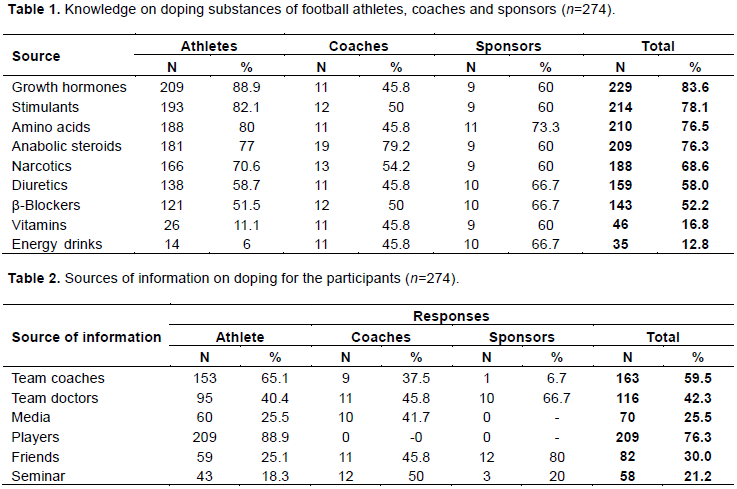

Table 1 shows the results on knowledge of participants on performance enhancing substances in football. Results in Table 1 show that football athletes and coaches identified hormones (88.9%), stimulants (82.1%), amino acids (80%), and anabolic steroids (77%) as performance enhancing substances. Coaches identified anabolic steroids (79.2%), narcotics (54.2%) stimulants and b-blockers (50%). Sponsors cited amino acids (73.3%), β-blockers (66.7%), diuretics (66.7%) and energy drinks (66.7%) as performance enhancing substances. Based on the 9 items on the list of performance enhancing substances in Table 1, it was expected that participants who scored 20 to 27 points were considered to have had high knowledge while participants scoring between 14 and 19 points were considered to have had medium knowledge on doping substances. Participants, who scored 13.5 points and below, were considered to have low knowledge levels on doping drugs. Results showed that among athletes (77%) had high, (22.1%), medium and (0.9%) and low knowledge levels, respectively. Sponsors (60%) had high, (20%), medium and (20%) and low knowledge levels. Coaches (45.8%) had high (8.4%), medium (45.8%) and low knowledge on doping substances. The sources of information on performance enhancing substances for athletes, coaches and sponsors are presented in Table 2.

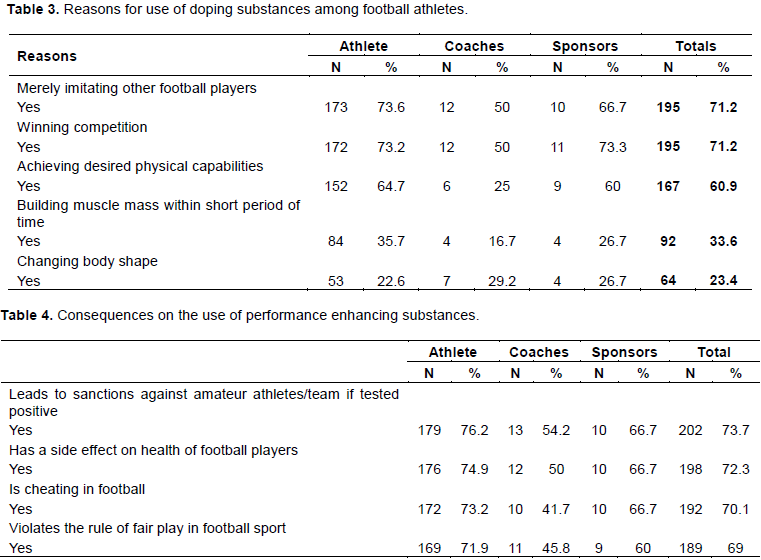

Results in Table 2 indicated that athletes mainly obtained information on doping from fellow players, coaches and team doctors. Coaches obtained information from seminars, team doctors and friends while sponsors obtained information from friends, team doctors and seminars. The perceived reasons for doping among the participants are presented in Table 3. Results in Table 3 show that athletes doped to imitate other athletes, to win competitions and achieve desired physical capabilities .Coaches and sponsors cited imitating other athletes and winning the competition as the main reasons for athletes to dope. Thus, winning competitions and imitating others featured highly among athletes, coaches and sponsors as the main reasons which spur athletes to dope. The consequences of the use of performance enhancing substances on athletes are presented in Table 4.

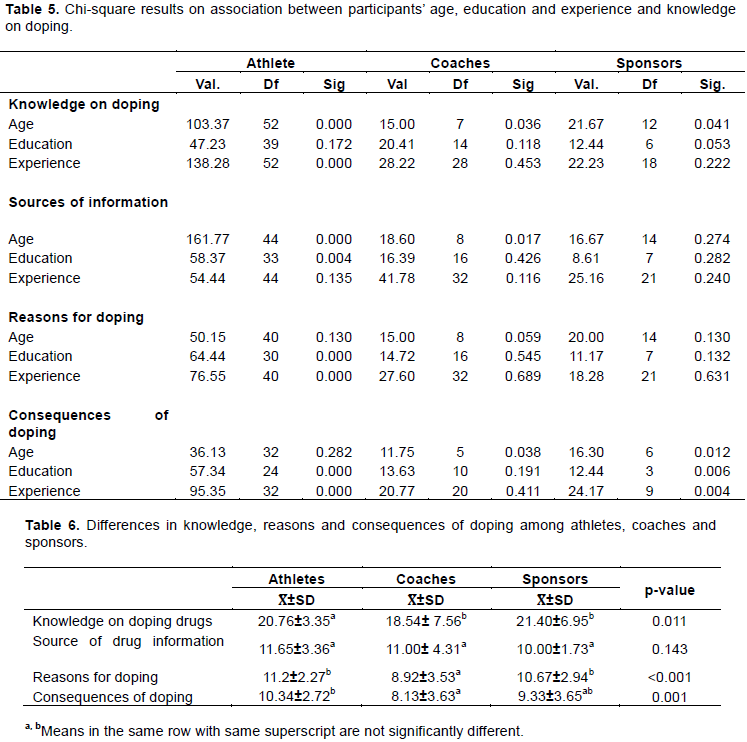

Table 4 shows that athletes,coaches and sponsors identified sanctions against positively tested athletes for doping, side health effects on the body of doping athletes , cheating in amateur football and violation of the rule of fair play in football as the main consequences of doping among football athletes in Malawi. The data were subjected to Chi Square test of independent measures to determine whether there were any significant associations between the independent variables (that is age, education and experience) and dependent variables (knowledge), and the results are presented in Table 5. Results in Table 5 show that there was a significant association between age of athletes (X2103.37, p<0.001), sponsors (X221.67, p=0.041) and knowledge on the use of performance enhancing substances. There was a significant association between age of athletes (X2 161, p = <0.001) and coaches (X218.60, p = 0.017) and sources of information on the use of performance enhancing substances. There was significant association between age of coaches (X211.75,p = 0.038) and sponsors (X216.30, p = 0.012) and consequences of use of performance enhancing substances on athletes. There were significant association between levels of education of athletes (X2 58.37, p = 0.004) and sources of information on doping substances (X2 64.44,p = <0.000) and reasons for doping. There were significant associations between experience of athletes(X2 138.28, p = <0.001) and knowledge on doping substances. Furthermore, there were significant associations between experience of athletes (X2 138.28, p = <0.001) and knowledge on use of performance enhancing substances (X2 76.55, p = <0.001) and reasons for doping (X2 95.35, p = <0.001) and consequences of use of performance enhancing substances. Table 5 further reveals that there was an association between experience of athletes and consequences of doping (X2 71.70, p = <0.001). Based on the results, the null hypothesis that there were no significant associations between demographic factors of football athletes, coaches and sponsors and their knowledge on doping was rejected.

One-way analysis of Variance (ANOVA) revealed that there were significant differences in knowledge on doping substances between athletes (20.76 ± 3.35) and coaches (18.54 ± 7.56) and between athletes (20.76 ± 3.35) and sponsors (21.40 ±6.95) p=.011; reasons for doping between athletes (11.25 ±2.27) and coaches (8.92 ±3.53) and between coaches (8.92 ±3.53) and sponsor (10.67 ± 2.94), p <.001 and on consequences of doping between athletes (10.34 ±2.72) and coaches (8.13 ± 3.63), p=.001. Post Hoc Tests showed that there were significant mean differences in knowledge on doping substances between athletes and coaches (MD = 2.22; p = 0.011) and between coaches and sponsors (MD = 2.86; p = 0.042). The tests further showed that there was significant mean differences on reasons for doping between athletes and coaches (MD= 2.33; p < 0.001), consequences of use of performance enhancing substance between athletes and coaches (MD= 2.22; p < 0.001). Therefore, the null hypothesis that there were no significant differences in knowledge among athletes, coaches and sponsors was rejected (Table 6).

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the knowledge on doping among football athletes, coaches and sponsors in Malawi. The specific items on knowledge which were assessed were doping substances, sources of information on doping, reasons for doping and consequences of doping. The findings of this study revealed that participants had generally high levels of knowledge on performance enhancing substances. In this regard, the athletes identified growth hormones, stimulants, amino acids and anabolic steroids as performance enhancing substances in football. These results are in agreement with those of Brown et al. (2013) who found out that 80% of elite sportspersons among football players (52%) in Ghana, had adequate knowledge of doping substances provided on the WADA list of banned substances. Similarly, college athletes in Kenya had demonstrated having knowledge on the list of banned substances (Kamenju, et al., 2016). However, these findings are contrary to those studies which reported that athletes had low knowledge on doping substances (Pavlovic and Idrizovic, 2013; Arazi et al., 2014; Chebet, 2014; Sekulic et al., 2014). For example, Arazi et al. (2014) found that 24.9% footballers in Iran had low knowledge on doping substances as they failed to identify β-Blockers and growth hormones on the list of banned substances by WADA. Equally, Chebet (2014) reported that athletes in middle and long distance running had low knowledge on doping substances in Kenya. Secondly, student- athletes in Bosnia and Herzegovina lacked adequate knowledge of doping substances (Pavlovic and Idrizovic, 2013). Therefore, the variations on the knowledge on doping among athletes could be attributed to lack of organized educational programmes on doping in different countries (Sekulic et al., 2014).

Football coaches (45.8%) and sponsors (60%) demonstrated high knowledge on doping substances. These findings were in agreement with results of studies which have been conducted elsewhere (Sas-Nowosielski et al., 2007; Judge et al., 2010; Bargi et al., 2015). For example in Poland, Sas-Nowosielski et al. (2007) found that sports coaches from various disciplines had higher knowledge on doping control methods and banned performance enhancing drugs. Our findings however, did not resonate with those of Judge et al. (2010) and Barghi et al. (2015) who found that certified coaches in the USA and Iran respectively had low knowledge on the use of performance enhancing substances, anti-doping rule violations and definitions on doping. For sponsors, Chien et al. (2016) opined that sponsors had knowledge on doping through published scandals in newspapers and broadcasts on televisions and radios. The knowledge of sponsors on the use of performance enhancing substances was tied to the risks of losing customers of their attached product once they were associated with doping scandals (Chien et al., 2016).

Participants in this study obtained information on doping from various sources such as coaches, team doctors and seminars. These sources of information on doping have been reported elsewhere (Brown et al., 2013; Kaur et al., 2014; Muwoge et al., 2015). For example, studies in Ghana and among British Olympic athletes found that coaches and team doctors were the main sources of information on doping respectively (Brown et al., 2013; Kaur et al., 2014). Muwoge et al. (2015) reported that athletes in Uganda obtained information of doping mainly from fellow athletes, team coaches and media. On the contrary, triathletes from Canada and United States indicated internet , family members and friends as the main source of information on doping whereas in Kenya, Athletics Kenya (AK), International Athletics Association Federation (IAAF) and internet were sources of information on doping among athletes (Johnson et al., 2013; Chebet, 2014).

Football coaches obtained information on doping from seminars, team doctors and friends. Our results support the assertion that coaches should actively participate in seminars in order to acquire important knowledge if protection of athletes from drug violations is to be achieved (Onuma et al., 2019). Our results differ from those of Mandic et al. (2013) who found that in Croatia and Serbia self-education was the principal source of information on doping among coaches and athletes. Furthermore, in Australia, the Tyrolean coaches indicated primary education and secondary training as the main sources of information on doping (Blank et al., 2015). Sponsors in this study obtained information on doping from friends , team doctors and seminars.It is regretable that the three groups of respondents did not utilise WADA website and internet as sources of information on doping.

The main reasons cited for the use of doping substances among football athletes included imitating other athletes, winning competitions, attaining desired physical capabilities, building body muscles for a short period of time and changing of body shape. These results have been reported in other studies in different countries such as in Turkey (Ozdemir et al., 2005), Spain (Sanchez et al., 2013), Bosnia and Herzegovina (Pavlovic and Idrizovic, 2013) and Saudi Arabia (Al Ghobain et al., 2016). Corluka et al. (2011)’s studies in Turkey and Bosnia showed that athletes doped to change body shape, build muscle mass and achieve targeted physical capabilities. Therefore, it appears that athletes in Malawi dope for similar reasons as those expressed by others in other parts of the world.

Our findings revealed that the three categories of participants identified sanctions against doping athletes, health side effects, cheating and violation of the rules of fair play as consequences of doping among amateur football athletes . These findings are supported in other studies in Saudi Arabia(Al Ghobain et al., 2016), Italy (Engelberg et al., 2011) where athletes knew health hazards, administrative sanctions and criminalization as consequences of use of performance enhancing substances. However, these findings contrast with those of other studies of Barghi et al. (2015) and Barbalho and Barreiros (2015) which reported that coaches had poor knowledge of side health effects of doping in athletes. For sponsors, Mohan (2016) argued that the reported use of performance enhancing substances by cyclists negatively affected sponsors in Spain. It had also been postulated that in the United States, sponsors were worried about doping issues which were under investigation regarding a cycling team sponsored by US Postal Service (Engelberg, et al., 2011). Moreover, Messner and Reinhard (2012) indicated that sponsors could exit sponsorship due to weird behaviors of athletes such as doping in order to safeguard the image of the promoted product.

Findings of this study revealed that there were significant associations between the demographic factors of participants and their knowledge on doping. First, there was a significant association between age of athletes and knowledge on PES. This is similar to findings in Bosnia, where the age of athletes was significantly associated with knowledge on doping, with older athletes scoring higher than younger athletes on knowledge on PES (Corluka et al., 2011). Sajber et al. (2013) found out that age of athletes and coaches were significantly correlated with knowledge about doping and sports nutrition, with older coaches having more knowledge than athletes in Croatia. Blank et al. (2015) found that age of coaches had a negative and low association with knowledge on the use of performance enhancing substances in Australia.

This study revealed that there was a significant association between levels of education of the participants and the reasons for doping and consequences of doping. This is not surprising as most of the participants had secondary school level of education. These findings concur with those of Muwonge et al. (2015) who found out that the education of students- athletes significantly correlated with reasons for use of performance enhancing substances in Uganda.

However, our study did not find any significant association between education and knowledge of doping and sources of information about doping substances. Participants relied on non-conventional means such as friends as sources of information on doping regardless of their educational status. This study revealed that there was a significant association between experience of athletes and knowledge on doping substances and consequences of doping. These findings were consistent with Sajber et al. (2013) and Angoorani and Halabchi (2015)’s studies which found that experience of athletes was significantly associated with knowledge on doping. In our study, there was no association between the experience of athletes, coaches and sponsors and the sources of information on doping. There were significant differences in knowledge on doping substances among athletes, coaches and sponsors. Athletes had highest knowledge on doping substances compared to sponsors and coaches. This was against the expectation that coaches would be on the lead in knowledge on doping substances as they are expected to inform athletes on the same. These findings were contrary to those by Engelberge et al. (2011) who found that there were no significant differences in knowledge on doping substances between athletes and coaches (Kim et al., 2007; Corluka et al., 2011; Blank et al., 2015). Florez, (2013) argues that incidences of use of performance enhancing substances become a concern to sponsors as they bring negative repercussions to their brands and products in sports by changing the attitudes of the consumers towards the sponsoring organization. Manouchehri et al. (2016) stated that unacceptable behaviors, including doping affect sports and sponsorship.

LIMITATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS

The current study on knowledge on doping had limitations and therefore the findings need to be interpreted with caution. First the study involved respondents from the cities of Blantyre and Lilongwe and therefore these findings may not be applicable to football athletes, coaches or sponsors from other parts of Malawi. Secondly, just like other studies on doping the criminal nature of doping may have negatively influenced the responses from athletes and coaches. However, the participants had been assured of confidentiality of their responses and this may have made the respondents to genuinely outline their knowledge on doping. The cross-sectional design of the study cannot be utilized to presume a cause-effect relationship between the variables of the study. However the findings of the study illustrate the status of doping among soccer participants in Malawi. Despite the above limitations, it is concluded that participants had knowledge on doping substances, with athletes having higher knowledge than the coaches and sponsors. The main sources of information on doping were coaches, fellow players and seminars. The reasons for doping among football athletes were imitating other athletes and winning competitions. Sanctions against positively tested athletes and side health effects were the commonly cited consequences of doping on athletes. There were significant associations between age of athletes and sponsors and their knowledge on doping substances. There was also significant association between level of education of athletes and source of doping. There was significant association between experience of athletes, coaches and sponsors and consequences of doping among athletes. Significant differences in knowledge on doping substances existed between athletes and coaches and between coaches and sponsors.

Based on the conclusions of the study, it is recommended that Malawi Government should formulate a deliberate policy for the fight against doping. Part of the policy would be to institute continuous training of coaches and athletes on anti-doping to enhance their knowledge and attitudes towards doping. The football sponsors in Malawi should insert anti-doping clauses in their conditions for their sponsorships in football as a measure for fighting doping. The Malawi Government should strengthen Malawi anti-doping organization to enable it establish doping programs that will impart knowledge on doping to athletes, coaches and sponsors. MADO should establish a website to share information and best practices that would enrich athletes, coaches and sponsor’s knowledge on doping in football. FAM in collaboration with MADO should have programs that will educate athletes on anti-doping. Further studies should be conducted with regard to the knowledge on doping based on coaching qualifications in football in Malawi. Studies should further be conducted on knowledge on doping of Athlete support personnel including parents, team managers and physicians in Malawi. Studies should also be conducted on knowledge on doping of football athletes and coaches at secondary school and tertiary levels in Malawi.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Al Ghobain M, Konbaz S, Almassad A, Alsultan A, Al Shubaili M ,AlShabanh O (2016). Prevalence, Knowledge and Attitudes of Prohibited Substances Use (Doping) among Saudi Sport Players. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention and Policy Journal 11(1):1-8.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Ama PFM, Betriga B, Ama Moor VJ, Kamaga JP (2003). Football and doping: Study of African Amateur Football and doping: Study of African amateur footballers. British Journal of Sports Medicine 37(4):307-310.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Angoorani H, Halabchi, F (2015). The Misuse of Anabolic-Androgenic Steroids amongIranian Re-Creational Male Body-Builders and Their Related Psycho-Socio-Demographic Factors. Iran Journal of Public Health 44(12):1662-1669.

|

|

|

|

|

Arazi H, Saeedi T, Sadeghi MM, Nastaran M, Mohammadi M (2014). Prevalence of Supplements Use and Knowledge Regard to Doping and it's Side Effects on Iranian Athlete University Students Participated in Sport Olympiad Competition at summer 2012. Acta Kinesiologica 8(2):76-81.

|

|

|

|

|

Atry A (2013). Transforming the Doping Culture: Whose Responsibility? What Responsibility Act a University. Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations, pp. 931-974.

|

|

|

|

|

Backhouse SH, McKenna J (2012). Reviewing Coaches' Knowledge, Attitudes and Beliefs Regarding Doping in Sport. International Journal of Sports Science and Coaching (7):167-175.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bae M, Yoon J, Kang H, Kim T (2017). Influences of Perfectionism and Motivational Climate on Attitudes towards Doping among Korean National Athletes: A Cross Sectional Study. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy 12(52)1-8.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Barbalho MDS, Barreiros FP (2015). The Use and Effect of Anabolic Androgenic Steroids in Sports. International Journal of Sports Science 5(5):171-179.

|

|

|

|

|

Barghi TS, Halabchi F, Dvorak J,Hossinnejad H (2015). How the Iranian Football Coaches and Players Know about Doping? Asian Journal of Sports Medicine 6(2)1-7.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Blank C, Furhapter, C, Leichtfried V, Mair-Raggautz M, Müller D, Schobersberger W (2015).Doping in Sports: Knowledge and Attitudes among Parents of Australian Junior Athletes. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports 25(1)116-124.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bloodworth AJ, Petroczi A, Bailey R, Pearce G, McNamee MJ (2012). Doping and Supplementation: The Attitudes of Talented Young Athletes. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports 22(2):293-301.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Brown AA, Poreko KKA,Eliason S (2013). Drug Use in Ghana: Knowledge, Perceptions and Attitudes in A Small Group of Elite Students Sports persons. Biomedical Human Kinetics 5(1):1-5.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Chebet S (2014). Evaluation of Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of Doping among Elite Middle and Long Distance Runners in Kenya:Unpublished (Doctoral dissertation, Kenyatta University).

|

|

|

|

|

Chien PM, Kelly SJ, Weeks CS (2016). Sport Scandal and Sponsorship Decisions: Team Identification Matters. Journal of Sports Management 30(5):490-505.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Corluka M, Gabrilo G, Blazevic M (2011). Doping Factors, Knowledge and Attitude on Doping among Bosnian and Herzegovinian Football Players.Kinesiologia Slovenica 17(3):49-59.

|

|

|

|

|

De Hon O, Kuipers H, Bottenburg M (2014). Prevalence of Doping Use in Elite Sports: A Review of Numbers and Methods: Review Article. Sports Medicine 45(1):57-69.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Dodge A, Robertson B (2009). Justification for unethical behavior in sport: The role of the coach. Canadian Journal for Women in Coaching 4:1-17.

|

|

|

|

|

Engelberg T, Moston S, Skinner J (2011). Athletes' and coaches' attitudes towards drugs in sport.

|

|

|

|

|

Fung I, Yuang Y (2006). Performance enhancing drugs: Knowledge attitudes and intended behavior among community coaches in Hong Kong. The Sport Journal 9(3).

|

|

|

|

|

Florez CL (2013). The Impacts of the Doping Effect on Cycling Sponsorship: Analysis of Brand Lovers and Cycling Fans Consumer Reaction. El fenómeno del dopaje 225.

|

|

|

|

|

Giraldi G, Union B, Masala D (2015). Knowledge, attitudes and behavior on doping and supplements in young football players in Italy. Public Health 129(7):1007-1009.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Johnson J, Butryn T, Masucci MA (2013). A Focus Group Analysis of the US and Canadian Female Triathletes' Knowledge of Doping. Sport in Society 16(5):654-671.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Judge LW, Bellar D, Petersen J, Gilreath E, Wanless E (2010). Taking Strides towards Prevention-Based Deterrence: USATF Coaches Perceptions of PED use and drug testing. Journal of Coaching Education 3(3):56-71.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kamenju J, Mwisukha A, Rintaugu EG, Muthomi H (2016). Teacher Trainee Athletes. Awareness of Selected Performance Enhancing Substances and Their Effects to Sports Performance. Journal of Physical Education and Sports Management 3(2):23-38.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kaur J, Masaun M, Bhatia MS (2014). Performance Enhancing Drug Abuse in Athletes and Role of Physiotherapy. Delhi Psychiatry Journal 17(2):413-418.

|

|

|

|

|

Kim J, Lee N, Kim EJ, Ki SK, Yoon J, Lee MS (2011). Anti-Doping Education and Dietary Supplementation Practice in Korean Elite University Athletes. Nutrition Research and Practice 5(4):349-356.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lentillon-Kaestner V, Carstairs C (2010). Doping use among young elite cyclists: A qualitative psychosociological approach. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports 20(2):336-345.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mandic GF, Peric M, Krzelj L,Stankovic S, Zenic N (2013). Sports Nutrition and Doping Factors in Synchronized Swimming: Parallel Analysis among Athletes and Coaches. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine 12(4):753-760.

|

|

|

|

|

Manouchehri J, Hamidi M, Sajadi, SN, Honari H (2016). Designing a Qualitative Model of Doping Phenomenon Effect on Sport Marketing in Iran. Sport, Leisure and Tourism Review 5(2):120-136.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Messner M,Reinhard MA (2012). Effects of Strategic Exiting from Sponsorship after Negative Event Publicity. Psychology and Marketing 29(4):240-256.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mohan P (2016). The Daily Edge, Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Morente-Sanchez J, Zandonai T, Zabala DM (2019). Attitudes ,beliefs and knowledge related to doping in different categories of football players. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 22(9):981-986.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mottram DR, Chester N (2018). Drugs in sport (7th Ed), London, Routledge.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Muwonge H, Zavuga R, Kabenge P (2015). Doping Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Ugandan Athletes: A cross-sectional study. Substance Abuse Treatment Prevention Policy 10(1):37.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Onuma N, Nakajima R, Abe M, Matsubara S, Matsuo E, Shindo D (2019). Attitudes toward Anti-Doping Education among Coaches of Youth Athletes. Journal of sports medicine and doping studies 9(1):1-8.

|

|

|

|

|

Ozdemir L, Nur N, Bagcivan I, Bulut O, Sumer H, Tezeren G (2005). Doping and Performance Enhancing Drug Use in Athletes Living in

|

|

|

|

|

Sivas, Mid-Anatolia: A Brief Report. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine 4(3):248-252.

|

|

|

|

|

Pavlovic R, Idrizović K (2013). Attitudes of Students of Physical Education and Sports about Doping in Sport. Physical Education and Sport 11(1):103-113.

|

|

|

|

|

Petroczi A, Aidman E (2008). Psychological drivers in doping: The Life-Cycle Model of Performance Enhancement. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention and Policy 3(1):7.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Petroczi A, Aidman E (2009). Measuring explicit attitude toward doping: Review of the psychometric properties of the performance enhancement attitude scale. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 10(3):390-396.

|

|

|

|

|

Sagoe D, Torsheim T, Molde H, Pallesen S (2014). Attitudes towards Use of Anabolic Androgenic Steroids among Ghanaian High School Students. International Journal of Drug Policy 26(2):169-174.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sajber D, Rodek J, Escalante Y, Olugic D, Sekulic D (2013). Sports Nutrition and Doping Factors in Swimming; Parallel Analysis among Athletes and Coaches. Coll Anthropol Suppl 1(2):179-186.

|

|

|

|

|

Sanchez JM, March MM, Zabala M (2013). Attitude towards Doping in Spanish Sport Sciences University Students According to the Type of Sport Practiced: Individual versus Team Sports. Science and Sports 30(2):96-100.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sas-Nowosielski K, Swiatkowska L (2007). The Knowledge of the World Anti-Doping Code among Polish Athletes and Their Attitude towards Doping and Anti-Doping Policy. Journal of Human Movement 8(1): 57-64.

|

|

|

|

|

Savulescu J, Faddy B, Clayton M (2004). Why we should allow performance enhancing drugs in sport British Journal of Sports Medicine 38(6):666-670.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sekulic D, Bjelanovic L, Pehar M, Pelivan K, Zenic N (2014). Substance Use and Misuse and Potential Doping Behaviour in Rugby Union Players. Research in Sports Medicine 22(3):226-239.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sharman I (2013). Old Mutual Two Oceans Marathon Men's Preview: I Run Far. Com. Mad, Mountain, Miles and More. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Thomas JR, Nelson JK, Silverman SJ (2011). Research Methods in Physical Activity. Human Kinetics.

|

|

|

|

|

Waddington I, Malcolm D, Roderick M, Naik R (2005). Drug use in English professional football. British Journal of Sport Medicine 39(4):e18-e18.

Crossref

|

|