ABSTRACT

Rabies is a serious fatal disease and a public health problem in Ethiopia. This study was conducted to investigate knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) related to rabies and its prevention and control amongst households in Nekemte town and its surroundings. A cross-sectional study design was used. A multistage sampling procedure with simple random sampling technique was employed to select households. The data were obtained from 384 households through face to face interview using pretested and structured questionnaires. Statistical Packages for Social Sciences Windows version 16.0 was used for data analysis. Findings were described using descriptive statistics and Pearson’s Chi square was used to show the association between outcome (KAP) and explanatory variables. Out of 384 respondents interviewed, 59.9% were males and 40.1% females, and 33.6% were between 15 and 30 years old. The majority of the respondents (47.4%) were protestant. Over 38.4% of the participants owned domestic dogs and 97.4% knew that dog bites transmit rabies. 53.1% participants had good level of KAP, making this outcome strongly associated with sex (χ²=18.06, p<0.08), age (χ²=85.4, p<0.001) and educational level (χ²=336.99, p<0.001). These findings indicate that the Nekemte community has good knowledge on rabies. But more work is required to raise the community knowledge regarding ways of infection, symptoms identifications, treatment measures as well as appropriate prevention methods.

Key words: Rabies, Ethiopia, clinical signs, animal bites, post exposure prophylaxis, Nekemte.

Rabies is an acute encephalitis illness caused by rabies virus in the genus, Lyssavirus and family, Rhabdoviridae. The virus affects almost all mammals and results in death once clinical signs are manifested (Jackson and Wunner, 2007). Worldwide, human mortality was estimated to be 55,000 deaths per year of which 56% occur in Asia and 44% in Africa. Rabies is endemic in developing countries of Africa and Asia (WHO, 1998) and about 98% of the human rabies cases occur in the developing nations (WHO, 2004). Rabies in humans was responsible for 1.74 million disability adjusted life years (DALYs) losses each year. The annual cost of rabies in Africa and Asia was estimated at US$ 583.5 million besides, in Africa and Asia, the annual cost of livestock losses as a result of rabies is estimated to be US$ 12.3 Million (Knobel et al., 2005). Rabies is endemic in Ethiopia as well and an estimated 2,700 people die each year, which is one of the highest rates in the world (CDC, 2016). In the country, it is estimated that there is one dog per five households nationally (Deressa et al., 2010) with poor management. In Ethiopia, individuals who are exposed to rabies virus often see traditional healers for the diagnosis and treatment of the disease. These widespread traditional practices of handling rabies cases are believed to interfere with timely seeking of PEP. Rabies victims especially from rural areas seek PEP treatment after exhausting the traditional medicinal intervention and usually after a loss of life from family members (Deressa et al., 2010).

The available information on rabies in Ethiopia is largely passive (Paulos et al., 2002; Eshetu et al., 2000). Passive reports usually underestimate the incidence and are poor indicators of the status of the disease in countries where human and animal health information systems are inadequate (Kitalaa et al., 2000; Kayali et al., 2003).

There is lack of accurate quantitative information on rabies both in humans and animals. Furthermore, little is known about the awareness of the people about the disease to apply effective prevention as well as control measures in Ethiopia. Therefore, the objective of this study was to determine the level of knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) of the community in Nekemte town on rabies.

Design of the study

This was a community based cross-sectional study, conducted from November 2015 to April 2016 in the community of Nekemte and surrounding areas. This community lives in 4 urban and 4 peri-urban Kebeles. A total of 384 people were selected from those communities live in and around Nekemte town. The human population includes both urban and peri-urban community. Community of all age groups and both sexes were asked.

Study area

The study area is Nekemte town located in east Wallaga in Oromia region. It is located 331 km south west of Addis Ababa. This town has a latitude and longitude of WikiMin9°5′N 36°33′E  /  / 11.850; 38.017with an elevation of 2088 m (6850 ft) above sea level. Based on 2007 National Census Conducted by the Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia, this town has a total population of 8456 of which 42121 are men and 4238385 women. The climate is warm and temperate. In winter, there is much less rain fall than in summer. The average annual temperature is 21°C. The average annual rain fall is 1497 mm (CSA, 2007).

Sampling process

The required sample size for this study was calculated using single proportion sample size determination (Thrusfield, 2005) considering 50% of population as knowledgeable to rabies at 95% confidence interval and 0.05 absolute precision. A multi-stage sampling technique was employed for the selection of the sampling units. From the entire primary sampling unit, that is, 7 administrative areas, 2 were selected by simple random sampling technique. Kebeles were selected from each administrative area by random method and the samples were distributed proportionally to sample size to each Kebele.

From the entire tertiary sampling unit, individual household, in the selected Kebeles was selected using a systematic random sampling technique. They were further selected by simple random sampling techniques and interviewed. A pretested structured questionnaire was used for this study. The data were collected via interview.

The questionnaire was first developed in English and then translated into Oromic language (native language) for appropriateness and easiness in approaching the study participants.

Data analysis

After collection, the data was cleaned and checked for its completeness. After complete checking-up, the data was coded and entered into Microsoft Excel and transported to Statistical Packages for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20. The frequency distribution of both dependent and independent variables were worked out by using descriptive statics techniques and association between independent variables and KAP scores on rabies was calculated using Pearson’s Chi square.

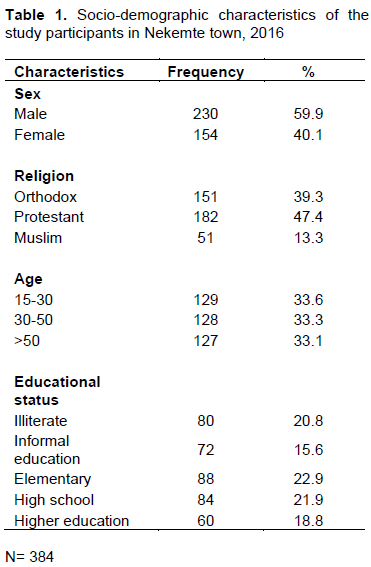

Socio-demographic characteristics

A total of 384 of the participants responded to the questionnaire yielding a response rate of 100%. Of these, 59.9% were males. 33.6% of the participants were aged between 15 and 30 years.

The majority of the respondents, 47.4% were Protestants followed by Orthodox 39.3%. Concerning educational status, 22.9% of the participants were at primary school level (Table 1).

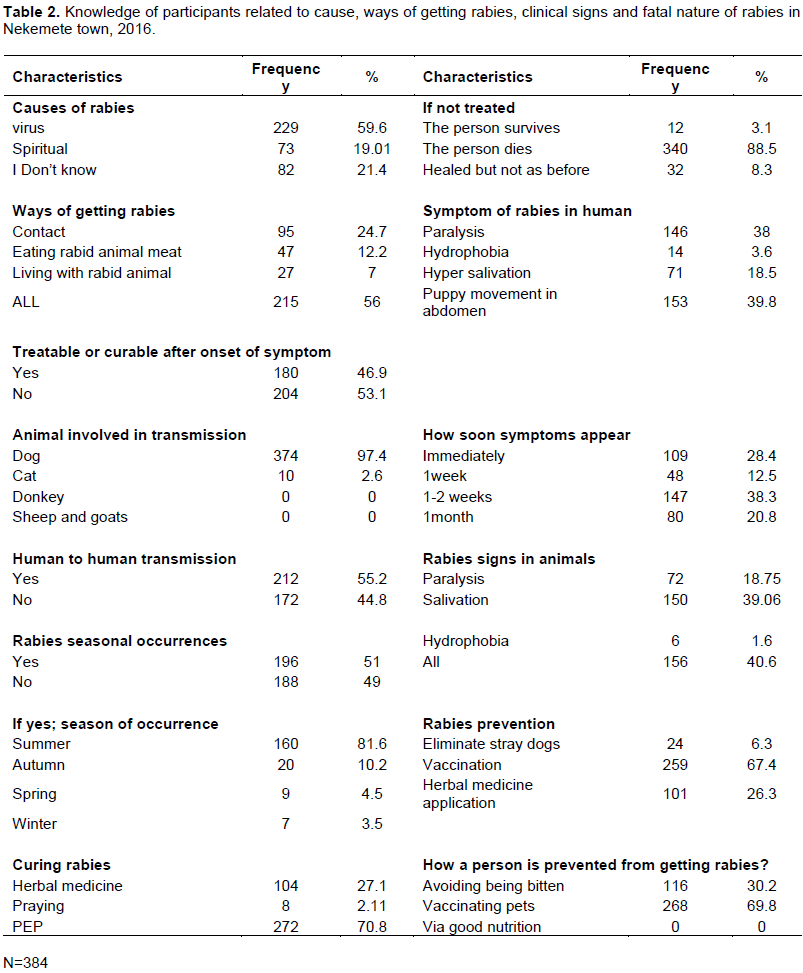

Knowledge of participants related to cause, ways of getting rabies, clinical signs and fatal nature of rabies

Of these respondents, 59.6% knew that virus is the cause of rabies, 97.4% were aware that dog is the most common source of rabies followed by cat 10 (2.6%) (Table 2). 39.6% of the respondents reported that hyper salivations are symptoms in rabid animals, while 18.75% mentioned that paralysis is manifested as sign. 78% of the respondents washed the wound with water and soap immediately, 35.7% seek health center, 45.8% had positive attitude for traditional healer. 90.7% of the participant identified dogs as the main animal, which transmit the disease, while 2.6% recognized the cat’s role in the transmission.

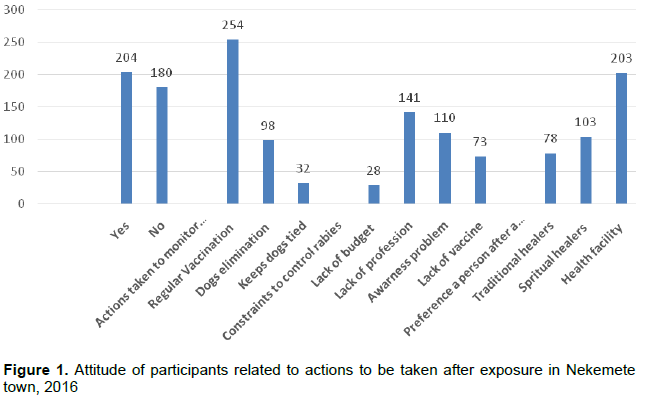

Attitude of participants related to action to be taken after exposure, whether cured after onset of symptoms, constraints of control rabies and where to go if bitten by a rabid animal

The attitude of participants regarding rabies was assessed. Attitudes related to action to be taken after exposure, whether cured after onset of symptoms, constraints of control rabies and where to go if bitten by a rabid animal were included for the purpose. From all respondents, 46.9% knows the fatal nature of rabies after the onset of clinical signs. Regarding constraints of controlling rabies, 36.7% reported that lack of veterinary professional contribute to control of rabies in Nekemte and 28.6% reported lack of awareness (Figure 1).

Community KAP about rabies in Nekemte town

Twenty three questions were asked for each respondent regarding cause, ways of infection, clinical sign, prevention practices and treatment measures of rabies which resulted in a response of either, choose the correct answer (one mark) or wrong answer (zero mark) for each question. The number of questions for which the respondent gave correct responses was counted and scored. This score was then pooled together and the mean score was computed to determine the overall KAP of respondents. Respondents who scored greater than or equal to the mean value (Mean=9.5) were grouped in good KAP and less than the mean value were grouped in poor KAP level. The data show that about 53.1% of the study participants were found to have good KAP on rabies and 46.9% were found to have poor KAP level.

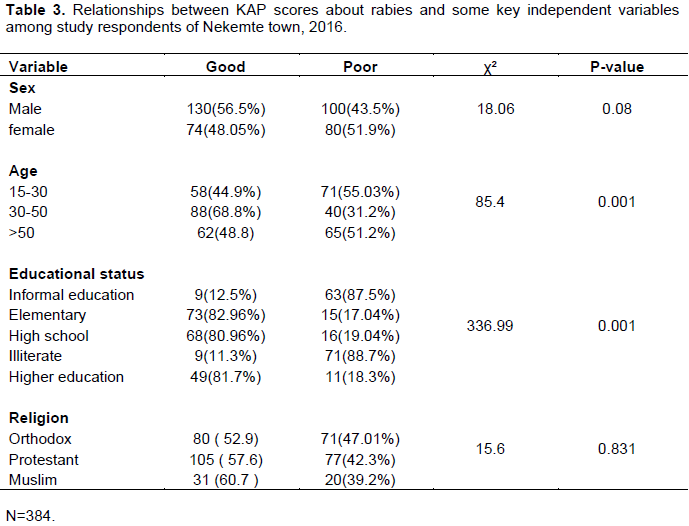

Factors associated with community KAP on rabies in Nekemte town

Association between independent variables and KAP scores on rabies was calculated using Pearson’s Chi square (Table 3). There was significantly association between KAP scores and sex χ² (= 18.06, p <0.08). There was also significant association between KAP scores and age (χ²= 85.4, p <0.00). The good scores were highest in the age group of 15-30 (69%) among other age groups. Educational status was significantly associated with KAP scores (χ²=336.99, p < 0.00). All the respondents in primary and secondary school and higher education levels had good KAP of rabies.

Despite its considerable negative effects, rabies in Ethiopia is among the neglected zoonotic diseases. In addition to this, there is little awareness regarding the disease and most prefer traditional managements either for the dog or their bites (Deressa et al., 2010; Yimer et al., 2002).

Of these respondents, 40.4% had misunderstanding of the cause of rabies, indicating that most of respondents believe that the disease in dogs is caused by spiritual and unknown cause. This KAP analysis revealed that 88.5% of respondents recognize rabies as danger and a fatal disease. This result is almost consistent with a study conducted in the city of New York, USA, reporting that 94.1% of the study participants know rabies as a killer disease (Hosmer and Lemeshow, 2000). The little difference may be due to presence of education on rabies in the town at this year. 97.4% of the respondent know that dogs are the most transmitters (source) of rabies. This result is almost consistent with a study conducted in the Gondar district reported that almost all respondent knows that dogs are most source of rabies followed by cats (Reta et al., 2015). The little difference may be due to presence of education on rabies in this town during this year. In this study, about 40.6% of the respondents were aware of common clinical signs of rabies in animals. This finding is supported by study done in Debre-Tabor (Awoke et al., 2015).

This study revealed that, 18.5% of the respondents know wound washing as an immediate action to mitigate the unnecessary outcomes after a dog bite. This result is highly lower than that of studies done in Bhutan where majority of respondents were aware of wound washing with soap and water after animal bite (Tenzin et al., 2012). This difference might be due to respondents believe, cultural set up and lack of awareness. In this study, 35.7% of the respondents used to visit health facilities to get medical care after being bitten by dogs, and this finding is almost in agreement with a study done in Sri Lanka where almost all the interviewed ones agreed to consult health professional in case of animal bite (Matibag et al., 2007). The slight difference appreciated between these studies might be due to differences in the information exchange as well as availability of health centers in immediate vicinity. 45.8% of the participants in Nekemte area showed strong belief on traditional medicine which is almost the same as study done in Gondar district in which 35% respondents prefer traditional medicine (Reta et al., 2015). Majority of the respondent indicated practicing regular dog vaccination as an effective measure to control rabies. This finding is not consistent with results recorded in Sir Lanka and Bahir Dar in which the majority of the participants were in favor of rabies control programs and mainly focused on stray dog population control (Matibag et al., 2009; Tadesse et al., 2014). The difference may be due to increased health extension activities and the role of mass media in utilization and importance of dog vaccinations as compared to mass killing.

The findings of this study indicated that, about 53.1% of the respondents had good level of knowledge, attitude and practices for rabies. In contrast to this finding, higher knowledge, more positive attitudes and higher scores in practice indicators regarding rabies was reported from Sri Lanka (Matibag et al., 2009). This difference probably is explained by the lack of health education programs on rabies in Ethiopia.

The current study indicated an association between KAP and Sex (p<0.08), age (p<0.001) and educational status (p<0.001). The difference by sex could be due to the fact that males usually stay away from house as compared to females and this could create an opportunity to have a better access for information. Besides, educated individuals would have better information and understanding on the disease than those who are not educated (Andrea and Jesse, 2012; Tadesse et al., 2014). The statistically significant difference in KAP scores among age groups might be due to increased reading capacity and eagerness to search for new things on rabies, as students. All respondents with primary, secondary and higher education levels had good KAP of rabies.

The possible explanation could be that educated person would have better information access and can easily understand the disease and this finding is also in agreement with reports made by Andrea and Jesse (2012) and Tadesse et al. (2014). Purposive selection of the study site is one of the limitations.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Information on local beliefs and practices can identify knowledge gaps that may affect prevention practices and lead to unnecessary deaths. This study reveals important knowledge gaps related to, and factors influencing the prevention and control of rabies in Nekemte town. Of the participants, 35.7% visited health facilities after suspected dog bite, 18.5% knew the value of wound washing after the bite, 40.4% misunderstood the cause of rabies and 88.5% knew rabies as a dangerous as well as lethal disease.

Based on this brief conclusion, raising the community awareness through continuous education, increase knowledge regarding wound washing, seeking post-exposure prophylaxis and the need to vaccinate dogs, collaboration between veterinary and human health professionals/offices, provision of pre and post exposure vaccines and creating rapid means of communications are suggested.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

|

Andrea M, Jesse D (2012). Community Survey after Rabies Outbreaks, Flagstaff, Arizona, USA. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 18(6):932.

|

|

|

|

Awoke A, Ashenafi A, Samuel D, Birhanu A (2015). Assessment of knowledge, attitude and practice on rabies in and around Debretabor, South Gondar, Northwest Ethiopia. Int. J. Basic Appl. Virol. 4(1):28-34.

|

|

|

|

|

Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2016). Rabies in Ethiopia.

View.

|

|

|

|

|

Central Statistical Authority (CSA) (2007). Sample enumeration report on livestock and farm implement. IV, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, pp. 26-136.

|

|

|

|

|

Deressa A, Ali A, Beyene M, Newaye B, Yimer E (2010). The status of rabies in Ethiopia: A retrospective record review. Ethiop. J. Health Dev. 24:12

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Eshetu Y, Bethlehem N, Girma T, Yared M, Yoseph B (2000). Situation of rabies in Ethiopia: A retrospective study 1990–2000. Ethiop. J. Health Dev. 16:105-112.

|

|

|

|

|

Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S (2000). Applied Logistic Regression, 2nd ed. New York: Wiley, pp. 92-97.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Jackson AC, Wunner WH (2007). Rabies. 2nd ed. San Diego: Academic press, pp. 309-340

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kayali U, MindekemR, Yémadji N, Oussiguéré A, Naýssengar S (2003). Incidence of canine rabies in N'Djaména, Chad. Prev. Vet. Med. 61:227-233.

Crossref2

|

|

|

|

|

Kitalaa PM, McDermotta JJ, Kyulea MN, Gathuma JM (2000). Community-based active surveillance for rabies in Machakos District, Kenya. Prev. Vet. Med. 44(1):73-85.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Knobel DL, Cleaveland S, Coleman PG, Fèvre EM, Meltzer MI, Miranda ME, Shaw A, Zinsstag J, Meslin FX (2005). Re-evaluating the burden of rabies in Africa and Asia. Bull. World Health Organ. 83:360-368.

|

|

|

|

|

Matibag GC, Ohbayash Y, Kanda K, Yamashina H, Kumara WR, Perera IN (2009). A pilot study on the usefulness of information and education campaign materials in enhancing the knowledge, attitude and practice on rabies in rural Sri Lanka. J. Infect Dev. Countries 3(1):55-64.

|

|

|

|

|

Matibag GC, Kamigaki T, Kumarasiri PVR, Wijewardana TG, Kalupahana AW, Dissanayake ADR, Niranjala De Silva DD, De S. Gunawardena GSP, Obayashi Y, Kanda K, Tamashiro H (2007). Knowledge, attitudes, and practices survey of rabies in a community in Sri Lanka. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 12(2):84-89.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Paulos A, Eshetu Y, Bethelhem N, Abebe B, Badeg Z (2002). A study on the prevalence of animal rabies in Addis Ababa during 1999-2002. Ethiop. Vet. J. 7:69-77.

|

|

|

|

|

Reta TD, Legesse GK, Abraham FM (2015). Knowledge, attitudes and practices towards rabies: questionnaire survey in rural household heads of Gondar Zuria District, Ethiopia. BMC Res. Notes 8:400.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Tadesse G, Anmaw S, Mersha C, Basazinew B, Tewodros F (2014). Assessment of Knowledge, Attitude and Practice about Rabies and Associated Factors: In the Case of Bahir Dar Town. Global Vet. 13(3):348-354.

|

|

|

|

|

Tenzin NKD, Bir DRC, Sangay T, Karma T, Pema U, Karma S, Michael PW (2012). Community based study on knowledge, attitudes and perception of rabies Bhutan. Int. Health 4(3):210-219.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Thrusfield M (2005). Veterinary epidemiology. 2nd Edition, Blackwell Science, Oxford, pp. 117-198.

|

|

|

|

|

World Health Organization (WHO) (1998). World survey of rabies, Geneva. P 32.

|

|

|

|

|

World Health Organization (WHO) (2004). First Report of Expert the WHO Consultation on Rabies: Technical Series No; 79. Geneva, Switzerland.

|

|

|

|

|

Yimer E, Newayeselassie B, Tefera T, Mekonnen Y, Bogale Y, Zewdie B, Beyene M, Bekele A (2002). Situation of Rabies in Ethiopia: A retrospective study 19 90- 2000. Ethiop. J. Health Dev. 16(1):105-112.

Crossref

|

|