ABSTRACT

Both suicide and economic crisis as terms are defined differently in scientific studies. Suicides before the crisis have several causes, and the proportion of such suicides during a crisis is unknown. Calculating these suicides as part of the purported economic crisis induced suicides may exaggerate the increase in the suicide rate. Suicide statistics is not reliable in all countries. Several years may pass before the economic crisis to make people conclude with a wish to and an act of committing suicide. People referred to hospitals before the crisis, during the crisis and some years after. The crisis could be characterized and compared according to objective and individually felt relation to deteriorating finances. The aim of the study is to demonstrate the complexity of the concept of suicide related to the economic crisis in Europe in 2007 to 2008 and propose a way to research this complexity.

Key words: Suicide, economic crisis, unemployment.

A committed suicide is seldoma disputed fact. Death is a final end-point. Suicides have intrigued the scientist and common man at least from the seminal works of Emile Durkheim. (Durkheim 1897; Werth 1996)The road to and reason for a suicide is complex and not fully understood, and reporting is unreliable (De Leo 2015). World Health Organisation (WHO) cautions against the validity of direct comparisons of suicide rates from different countries, also outside periods with an economic crisis. While WHO firmly discourages the practice of straight data comparisons between countries, nobody actually seems to care (De Leo 2015). Reasons for this deplorable data insufficiency are many; stigma avoidance, legal or religious pressure against reporting, self-starvation, voluntary euthanasia, methods of suicide as motor vehicle accidents and opiate overdose, and missing persons. Thus, even before an official statement of death due to suicide on a death certificate form, many factors contribute to uncertainty. Countries have different routines and responsibilities for investigation procedures and issuing of death certificates.

An economic down turn or crisis has an impact on suicide rates, and often also on the unemployment rate. Both terms may interact during a crisis, but empirical studies vary widely. The study proposes that a too simplified notion of suicide and unemployment is used in epidemiological and public health studies of changes in societies. In a study by Laanani et al. unemployment and suicide rates were found to be statistically associated, but very weakly (Laanani et al. 2014). A "crisis effect" was inconsistent across countries and was interpreted as an argument against a causal effect. Impact of unemployment on suicide rates is shown to be offset by the presence of generous state social and unemployment benefit programs (as in Norway), though effects are small or inconclusive (Baumbach and Gulis 2014; Cylus et al. 2014). Reeves et al. found an 0.94% increase in male suicide rates for each percentage point rise in unemployment in 20 European Union (EU) countries with widely varying social welfare programs (Reeves et al. 2014a).

The economic crisis in Europe in 2007 to 2008 has started a renewed interest in a purported effect of an economic downturn on the rates of suicides in society (Chang et al. 2013). Attitudes towards suicide have changed considerably through history from a question of moral sentiment to a medical, psychological or public health problem (Fitzpatrick 2014). Committed suicides have rates that differ with age, sex, work conditions and employment status. Whereas, women in rural India commit suicide out of poverty and harsh family relations using pesticides (Mohanraj et al. 2014), old men in Norway (suicide rate above 70 years 29.8/100000 in one study (Kjølseth et al. 2002)) and other European countries find their lives useless and have a rate higher than in the working age groups. When suicide is not accepted in society, even national statistics may be inaccurate or rather report low suicide rate. An eruption of publications started in the light of the Orthodox Church in Greece stating that suicide is a deplorable moral act, and an ensuing underestimation of suicide cases in the public statistics. This was very prominent when the economic downturn of 2007 made living conditions deteriorate as shown in a study by Kentikelenis et al. 2014.

This study is firmly contested by Konstantinos et al mentioning that suicide rates have increased in countries without crisis Fountoulakis and Theodorakis 2014. Several articles have highlighted the impact of the crisis on mental health, usually through suicide, although mental health problems are not the only reason for a suicide during a crisis. A recent editorial in Lancet underscore the ill effect of austerity measures. (Editorial 2015) The imputed increasing suicide rate in Greece after 2008 has been studied extensively. (Stuckler et al., 2009, Kentikelenis et al., 2011, Costa et al., 2012, De Vogli et al., 2013, Fountoulakis et al., 2013, Kondilis et al., 2013, McDaid et al. 2013). On the other hand the total health impact of the economic downturn in the short run has been positive in 23 European countries (Toffolutti and Suhrke 2014). All cause mortality decreased 3.4% at the increase of 1.0% in unemployment rate, even motor vehicle accidents and alcohol related deaths decreased, whereas the suicide rate increased by 34.1%.

The quality of suicide statistics hinges on the quality of mortality statistics in a country (De Leo 2015). In 2012 in Norway, 530 persons committed suicide and around 240 died after an overdose of a narcotic substance, mainly heroin. A clear distinction between the two ways of dying would be hard to come by, even if every heroin overdose is defined as not a suicide. If on the other hand both ways of dying would be part of the suicide statistic, the suicide rate in Norway would in fact be 50% higher than the published one. On the other end of mortality statistic, observations of artificially low suicide rates in Greece may have a cultural background. Death certificates issued by medical doctors are usually the input to mortality statistic tables. Handling of violent or self-inflicted deaths may be subject to religious or discretionary demands. Even if the statistics are reliable, the relationship between unemployment and suicide is not monolithic (Jalles and Andresen 2014). It may change for different demographic groups, places and sex.

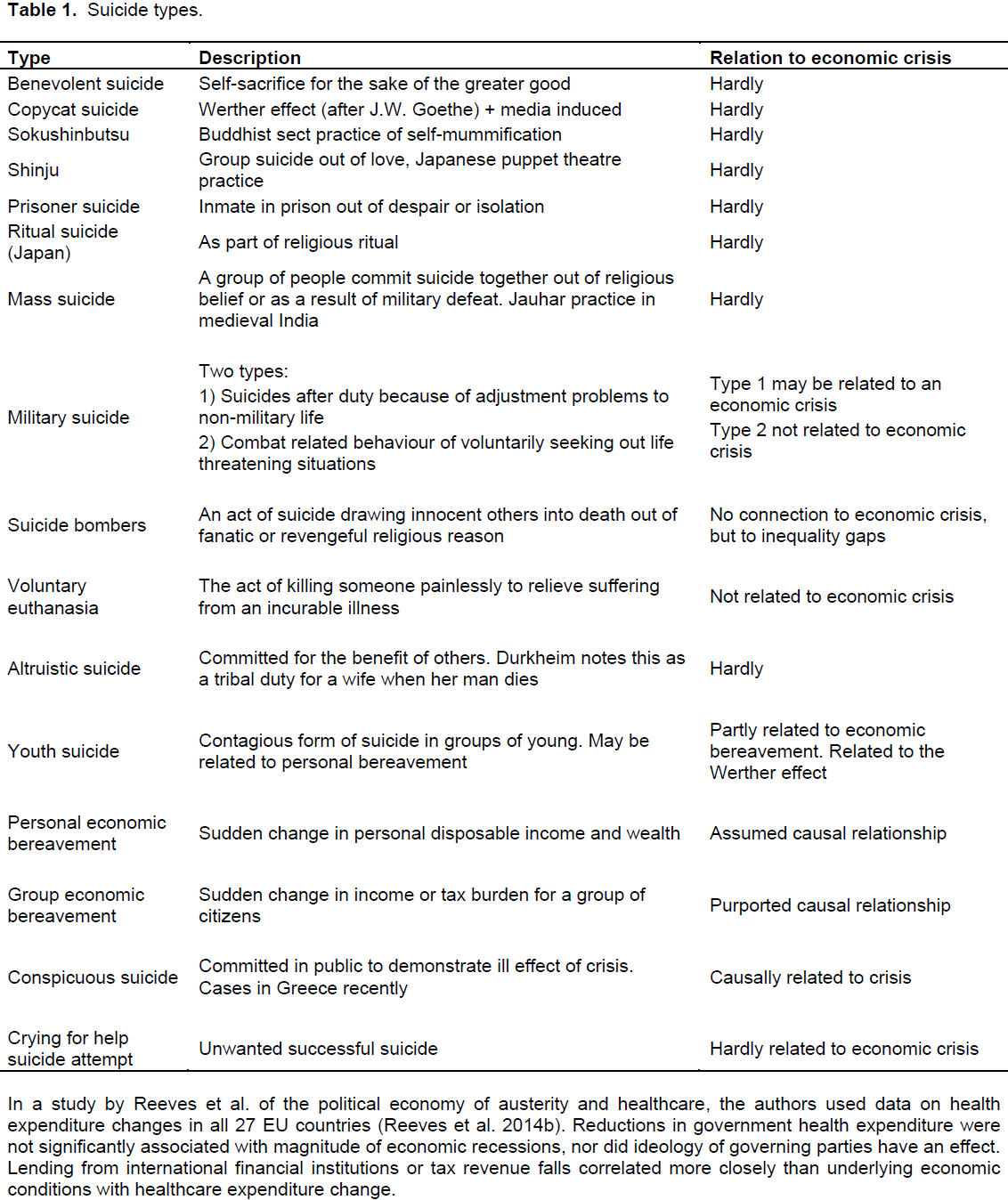

Several reasons for suicide are known. A not comprehensive outline of types of suicides is given in Table 1. The type of suicide varies along cultural, religious and political lines. To the study knowledge the proportions of suicides in a country has not been estimated according to the groups depicted in Table 1. During an economic crisis nearly all suicides are thought to be the result of the crisis. Time lag between an economic crisis and committing suicide is an unknown factor. A suicide during the economic crisis may have its root in events before the crisis. Events during the crisis that could drive people to a suicide may not be judged as related to the crisis because of a long time lag before it happens.

Overview of the concept of suicide

Table 1 lists different types of suicides and their purported relationship to an economic crisis. Most types are deemed not related to a crisis, although the numbers would be included in the suicide statistics.

An increase in suicide rates during the economic crisis in 2007 and the following years would have to be encompassed by Table 1. Mental illness is known to

increase the risk of suicide above the risk in the general population. Mental illness is not a uniform entity and the work force participation rate differs greatly, and little is known about whom with a mental illness commit suicide.

1. Persons with a psychotic illness may never have worked. If they commit suicide, the relation to the economic crisis is not straightforward.

2. Persons with a minor mental illness in the work force may have difficulties staying in the job, also in good times. The effect of sudden unemployment may drive some into suicide and this would be a case of crisis-

induced suicide.

Military service men and women commit suicide for reasons related to the military service or the great change in life circumstances after ending military service. The relation to a concomitant economic crisis is uncertain. The road from suicidal ideation to committing suicide may be influenced by increased emphasis on awareness to live and being connected to others as shown in a qualitative paper from Norway (Vatne and Nåden 2014). Data from Greece on suicides are unreliable out of cultural reasons. Thus, the reported increase in Greece of suicide rates during the last economic downturn may be an artefact of statistical registration.

Sparse social security nets would increase the negative consequences of a recession, as might be the case for Hungary. The substantial decrease in suicide rates, from a very high level over the last 30 years in Hungary, is a counter example of no positive relation between an increase in economic crisis and an increase in suicide rates. As would the steady rate of suicides in Norway be in a period with improved social security net. The unemployment - suicide link was studied in 30 countries spanning the period 1960 to 2012 (Norström and Grönqvist 2014). The possible excess effect of un-employment during the financial crisis was not significant in the fixed effects model of the authors. More generous unemployment protection implied a weaker detrimental impact on suicide of the increasing unemployment during the Great Recession.

Table 1 indicates that the fraction of suicides related to an economic crisis in a country is unknown. The seven first types of suicide are hardly related to the crisis, whereas they may constitute a non-negligible part in some countries. Before the economic crisis we do not register whether a suicide is related to the same economic mechanisms as during the crisis. Suicides do not necessarily occur immediately after the proclamation of an economic crisis. If a suicide occurs some years after the start of an economic downturn there is no agreement as to a purported causal relationship.

Inferences from existing datasets should therefore be more tentative than in some recent publications. The results for Hungary are further explained by a study by Fountoulakis et al 2014b. Using a dataset from 2000 to 2011 they suggest that unemployment might be associated with suicidality in the general population only after 3to 5 years. It is possible that the distressing environment of the economic crisis increases suicidality in the general population rather than specifically in un-employed people. Spectacular suicides published in media shortly after the start of an economic downturn probably represent a marginal phenomenon, but may increase slightly the numbers of suicides for some days (Ueda et al. 2014). The media coverage rather than the co-occurrence with an economic downturn would explain this short-term rise in suicides.

How could we improve the studies on suicide rates related to economic changes?

Characterizing suicidal events may be achieved by studying persons referred to medical or psychiatric departments before a crisis emanates, during the crisis and some years after. This would not be a cohort study. Data on socio-economic circumstances, concomitant mental problems characterized in some detail and the relation to a crisis cycle must be gathered. Objective economic parameters may be compared to individually felt economic restrictions. This may be done both by quantitative and qualitative methods, also lagged regression models and relevant psychometric tests.

The fraction of people succeeding in committing suicide without being referred to hospital cannot be characterized by such a study. However, in most cases a suicide outside hospital does leave researchable traces of information. The distinction of military personnel described earlier may very well be studied by the proposed methods. Inaccurate mortality statistics would not pose a problem. Comparisons across countries could be done. Violation of the warnings by WHO would, with the proposed methods, not be relevant.

The author has none to declare.

REFERENCES

|

Baumbach A, Gulis G (2014). Impact of financial crisis on selected health outcomes in Europe. Eur. J. Public Health 24(3):399-403.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Chang SS, Stuckler D, Yip P (2013). Impact of 2008 global economic crisis on suicide: time trend study in 54 countries. Br. Med. J 347.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Costa G, Marra M, Salmaso S (2012). [Health indicators in the time of crisis in Italy]. Epidemiol. Prev. 36(6):337-366.

|

|

|

|

|

Cylus J, Glymour M, Avendano M (2014). Do generous unemployment benefit programs reduce suicide rates? A state fixed-effect analysis covering 1968 - 2008. Am. J. Epidemiol. 180(1):45-52.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

De Leo D (2015). Can we rely on suicide mortality data? Crisis 36(1):1-3.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

De Vogli R, Marmot M, Stuckler D (2013). Strong evidence that the economic crisis caused a rise in suicides in Europe: the need for social protection. J. Epidemiol. Comm. Health 67(4):298-298.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Durkheim E (1897). Le Suicide. (The suicide). Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Editorial (2015). The Greek health crisis. The Lancet 386 (July 11):104.

|

|

|

|

|

Fitzpatrick SJ (2014). Re-moralizing the suicide debate. Bioethical Inquiry. doi: 10.1007/s11673-014-9510-y.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Fountoulakis K, Gonda X, Dome P, Theodorakis P, Rihmer Z (2014). Possible delayed effect of unemployment on suicidal rates: the case of HUngary. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 13(12).

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Fountoulakis K, Theodorakis P (2014). Austerity and health in Greece. The Lancet 383(May 3):1543.

|

|

|

|

|

Fountoulakis KN, Savopoulos C, Siamouli M, Zaggelidou E, Mageiria S, Iacovides A, Hatzitolios AI (2013). Trends in suicidality amid the economic crisis in Greece. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 263(5):441-444.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Jalles J, Andresen M (2014). Suicide and unemployment: a panel analysis of Canadian provinces. Arch. Suicide Res. 18(1):14-27.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kentikelenis A, Karanikolos M, Papanicolas I, Basu S, McKee M, Stuckler D (2011). Health effects of financial crisis: omens of a Greek tragedy. The Lancet 378(9801):1457-1458.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kentikelenis A, Karanikolos M, Reeves A, McKee M, Stuckler D (2014). Greece's health crisis: from austerity to denialism. The Lancet 383(February 22):748-753.

|

|

|

|

|

Kjølseth I, Ekeberg Ø, Teige B (2002). Suicide among the elderly in Norway. Tidsskr Nor Legeforen 122(15):1457-1461.

|

|

|

|

|

Kondilis E, Giannakopoulos S, Gavana M, Ierodiakonou I, Waitzkin H, Benos A (2013). Economic Crisis, Restrictive Policies, and the Population's Health and Health Care: The Greek Case. Am. J. Public Health 103(6):973-979.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Laanani M, Ghosn W, Jougla E, Rey G (2015). Impact of unemployment variations on suicide mortality in Western European countries (200-2010). J. Epidemiol. Comm. Health 69 (8):819-20.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

McDaid D, Quaglio G, Correia de Campos A, Dario C, Van Woensel L, Karapiperis T, Reeves A (2013). Health protection in times of economic crisis: challenges and opportunities for Europe. J. Public Health Policy 34(4):489-501.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mohanraj R, Kumar S, Manikandan S, Kannaiyan V, Vijayakumar L (2014). A public health initiative for reducing access to pesticides as a means to committing suicide: findings from a qualitative study. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 26(4):445-452.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Norström T, Grönqvist H (2014). The Great Recession, unemployment and suicide. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 69(2):110-6.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Reeves A, McKee M, Basu S, Stuckler D (2014). The political economy of austerity and healthcare: Cross-national analysis of expenditure changes in 27 European nations 1995-2011. Health Policy 115:1-8.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Reeves A, McKee M, Gunnell D, Chang SS, Basu S, Barr B, Stuckler D (2014). Economic shocks, resilience, and male suicides in the Great Recession: cross-national analysis of 20 EU countries. Eur. J. Public Health 25(3):404-9.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Stuckler D, Basu S, Suhrcke M, Coutts A, McKee M (2009). The public health effect of economic crises and alternative policy responses in Europe: an empirical analysis. The Lancet 374(9686):315-323.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Toffolutti V, Suhrke M (2014). Assessing the short term health impact of the Great Recession in the European Union: A cross-country panel analysis. Prev. Med. 64: 54-62.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ueda M, Mori K, Matsubayashi T (2014). The effects of media reports of suicides by well-known figures between 1989 and 2010 in Japan. Int. J. Epidemiol. 43(2):623-629.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Vatne M, Nåden D (2014). Crucial resources to strengthen the desire to live: Experiences of suicidal patients. Nursing Ethics Dec 24. pii: 09697330145629901-14.

|

|

|

|

|

Werth JL (1996). Rational suicide? Implications for mental health professionals. Taylor & Francis.

|

|