This research article presents a comparative study of the adsorption properties of Moringa oleifera biomass using Pb2+ ions as test analyte. The investigated parameters which affected the adsorption process were the effect of pH, initial concentration, adsorbent dose, contact time, and temperature. The comparison of adsorption process was evaluated in the pH range of 3 to 8, concentration range from 5 to 20 ppm, temperature varied from 25 to 80°C, variation of contact time from 15 to 80 min, and dose of the adsorbent from 0.3 to 1.2 g. The results obtained showed that a high adsorbent dose is required for high adsorption capacity. The pH of 7 was most effective with temperature set at 25°C and contact time of 60 min. The Temkin, Dubunin-Radushkevich, Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms were applied and fitted well to the data and values of the parameters of these isotherm equations were calculated. The Langmuir isotherm proved to be the overall best isotherm. The adsorbent surface functional groups were identified with Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. The maximum adsorption capacity obtained was 98% for seed, 96% for blended, 94% for pods, and 92% for leaves. Better thermodynamic and kinetic properties were obtained with the seeds and the blended samples. In total, these results indicate that the blended moringa biosobent can be employed as a low-cost biosorbent for the removal of lead ions from water.

Industrial activities and technological developments have led to the discharge of heavy metals into the environment. These heavy metals are toxic to humans and other forms of life because they are non-biodegradable hence accumulate in living organisms (Das et al., 2008; Kakalanga et al., 2012). Lead is among the most dangerous and most prevalent heavy metals from industrial processes (Kakalanga et al., 2012; Deng et al., 2008), which is extensively used in many important industrial applications such as battery manufacturing, printing, photographic materials, explosive manufacturing, coating, and steel industries (Kaya et al., 2009; Babarinde et al., 2012). Lead is toxic at low concentrations hence used as a test analyte in this study.

According to World Health Organization (1984), permissible limit for lead in drinking water is 0.05 mg/L. Higher concentrations of lead ions in drinking water can damage nervous connections and cause blood and brain disorders, miscarriage, damage to sperm producing organs, and may result in death (Kaya et al., 2009; Khan et al., 2008; Igwe et al., 2006; Yakan et al., 2008; Memon et al., 2008; Adebayo et al., 2012). Thus, removal of toxic heavy metals such as lead is essential in environmental pollution control (El-Sayed et al., 2011). Conventional method for water treatment such as chemical precipitation, ion exchange and reverse osmosis are often costly and have inadequate efficiencies at low metal ion concentrations.

Such procedures can generate toxic sludge hence the ultimate need for cheaper and effective procedures. Recently, the need for new technologies involving the removal of toxic metals from waste water has directed attention to biosorption due to low cost, free availability, high adsorption, possible reuse and flexible operation (Yang et al., 2009; Volesky, 2003; Park et al., 2010; Safa and Bhatti, 2011). Moringa oleifera husks have recently been used as biosorbents for determination of lead in chicken feed (Oliveira et al., 2017). However, a comparative analysis of different M. oleifera parts has not been done side-by-side.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to investigate the possibility of the utilization of different parts of M. oleifera plant, and find which part has greater capacity for adsorption of Pb2+ ions as well as the effects of blending leaves, pods and seeds on biosorption using Pb2+ ions as the test analyte. M. oleifera biomass has been chosen since it has known medicinal properties hence the adsorbent will also have an antibacterial activity during the water treatment process. The biosorbent is envisaged to have both heavy metal adsorption and antimicrobial properties in the treatment of contaminated water. This report gives a comprehensive side by side adsorption characterization of M. oleifera parts and the blended composition for sorption of Pb2+ in water. The Temkin, Dubinin-Radushkevich, Freundlich and Langmuir isotherms have been used to describe the experimental equilibrium data.

Equipment

The concentrations of Pb2+ in the solutions before and after biosorption were determined by FAAS (ThermoFisher AA-6800). The pH of the solution was measured using a pH meter (Orion Star A211) brined glass electrode. Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectrometer (Nicolet IS5) was used to identify the different functional groups present in the M. oleifera samples before and after removing Pb2+. FTIR analyses were also used to determine the functional groups responsible for the Pb2+ binding with M. oleifera samples. The agitation was carried out by Reciprocated Shaker (HY-4).

Sample preparation

After sourcing, the seeds were removed from the fruit (called drumsticks). The seeds and pods were dried separately for about 2 weeks. The moringa leaves were also removed from the main plant and were placed at an open shelf in the laboratory for air drying for two weeks. The pods, seeds and leaves were ground separately to powder using a mechanical grinder. The powdered leaves, pods and seeds samples were sieved through 0.25 mm sieves. Blended M. oleifera sample (leaves, pods and seeds) was prepared by using a mixing ratio of 1:1:1 and mixed in a grinder for 2 min.

Biomass treatment

The method described by Mahmood et al. (2010) was modified and adopted in the treatment of the biosorbent. Each sample (8 g) weighed by analytical balance (GA110) was treated independently with 1000 ml, 0.1 M HCl with continuous stirring for 2 h to remove metals from the biosorbent and increase its surface area. It was washed with 500 ml deionized water; this was done three times, and then the sample was sundried for about 6 h. After the acid treatment, about 5 g of each sample was cleaned with 400 ml methanol to remove inorganic and organic matter from the sorbent surface. This was carried out for 2 h 30 min. The adsorbent pH was adjusted to 7 using 0.1 M NaOH, washed with deionized water, oven-dried for about 1 h. It was placed in an air-tight plastic container and put in a refrigerator at 4°C prior to analysis.

Solubility determination

Moringa samples (5.000 g) were weighed separately and transferred to a volumetric flask with 500 ml deionized water left stoppered for 24 h so as to dissolve all the soluble components (Qaiser et al., 2009). The mixture was filtered using vacuum filtration and the residue was collected, air dried for 3 h and oven dried at 65°C until a constant mass was obtained. Percentage solubility was calculated using Equation 1.

% Solubility = 100 (m1 - m2 / m1) (1)

Where, m1 and m2 are masses of moringa samples before and after dissolution, respectively.

Characterization of biomass

The FTIR was used to determine the functional groups present in the moringa samples before the adsorption. Moringa samples were analyzed in the range 400 to 4000 cm-1. KBr was used as background material.

Preparation of stock solutions and calibration standards

Stock solution of Pb2+ was prepared by dissolving 1.599 g of Pb (NO3)2 (Analytical grade, Sigma Aldrich) and making the solution to 1 L mark in a volumetric flask. The solutions contained 1.000 μg/cm3 (1000 ppm) of Pb2+. These solutions were used to prepare calibration standards of 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 ppm for lead.

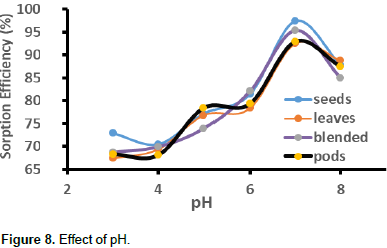

Effect of pH

The effect of pH on biosorption of Pb2+ ions was determined with the pH values 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 keeping the concentrations of metal ions at 20 ppm at room temperature (~25°C). The pH was adjusted using 0.1 M HCl and 0.1 M NaOH. 50 ml solutions of Pb2+ were transferred into conical flasks, 0.4 g of M. oleifera samples were added and the solution was shaken for 1 h at 150 rpm. The solutions were filtered and the filtrate was analyzed on the FAAS.

Effect of contact time

The effect of contact time on the process of biosorption was studied at the following time intervals 25, 40, 60, and 80 min at optimum pH of 7 at room temperature. 50 ml of 20 ppm Pb solution and 0.5 g of M. oleifera samples were transferred into conical flasks. The solutions were shaken at 150 rpm at different time intervals. The solutions were filtered and filtrate was analyzed on the FAAS.

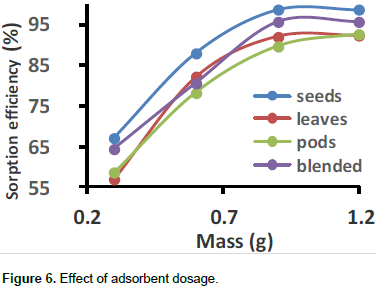

Effect adsorbent dosage

To determine the effect of adsorbent dose, different amounts of 0.3, 0.6, 0.9 and 1.2 g of M. oleifera samples were suspended in 50 ml of 20 ppm Pb at room temperature. The solutions were transferred into conical flasks and left to shake at 150 rpm under optimum pH of 7 and contact time of 60 min. The solutions were filtered and the filtrate was analyzed on the FAAS.

Effect of initial ion concentration

The effect of initial concentration on the biosorption process was investigated under optimum conditions. 50 ml solutions of 5, 10, 15, and 20 ppm concentration of Pb were left to shake at 150 rpm at optimum pH of 7, contact time of 60 min, and biomass dosage of 0.4 g at room temperature. The solutions were filtered and the filtrate was analyzed on the FAAS.

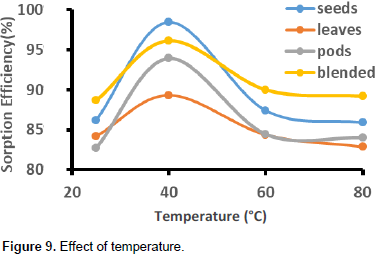

Effect of temperature

The effect of temperature on the process of biosorption was studied at the following temperatures 25, 40, 60, and 80°C at the optimum pH of 7 and 50 ml of 20 ppm Pb and 0.5 g of moringa samples were transferred into conical flask. The solutions were shaken at 150 rpm at different temperatures. The solutions were filtered and filtrate was analyzed on the FAAS.

Solubility determination

Solubility of M. oleifera samples was calculated using the Equation 1. The percentage of M. oleifera biomass recovery for different sample was 12.9% for leaves, 5.45% for pods, and 23.5% for seeds. There was a greater amount of sorbent components dissolved in the aqueous solution for all the sample sorbents and it does not participate in the sorption process.

FTIR analysis

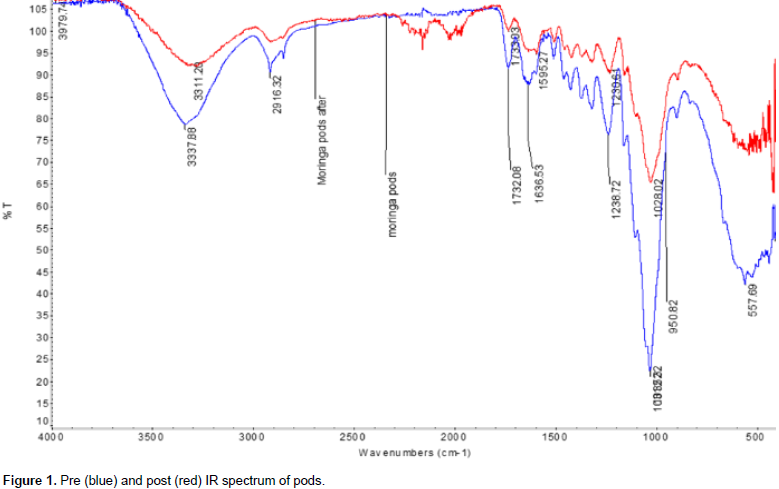

The functional groups present in the moringa samples (pre and post Pb2+ adsorption) were determined using the FTIR spectroscopy. Figure 1 shows that the absorption at 3337.88 cm-1 in M. oleifera pods is due to OH stretching vibration (Kumar and Tamilarasan, 2013; Zhang et al., 2013; Sivaraj et al., 2001). Vibrations at 2916.32 cm-1 was due to CH stretching and 1732.08 cm-1 could be C=O (carbonyl) stretch (Lee et al., 2007). Vibrations at 1636.72 cm-1 can be ascribed to aromatic C=C bending or NH of an amide; 1238.72 and 1083.3 cm-1 were assigned to C-O group of an acid and an ester, respectively (Sharma and Uma Gode, 2010). M. oleifera pods loaded with Pb2+ show the absorption peaks at 3337.88 cm-1 with the intensity of the peak shifted to 3311.29 cm-1.

This could be the stretching of the OH group due to the absorption. The disappearance of the sharp peak at 916.32 cm-1 could be the result of the C-H stretching involvement in absorptions. Absorption peak 1733.08 cm-1 lost intensity and shifted to 1730.08 cm-1 due to the stretch presence of C=O functional group of the carboxylic acids involvement in Pb2+ absorption. Repeated changes were also noted in the natural composition of M. oleifera pods which is the existence of peaks at wave number of 1238.72 and 1083.32 cm-1. The repeated shift due to the C-O stretching suggests that C-O might be a functional group that Pb2+ can bind and react with it. The subsequence shift in the absorption peaks indicates the binding process on the surface of the M. oleifera pods.

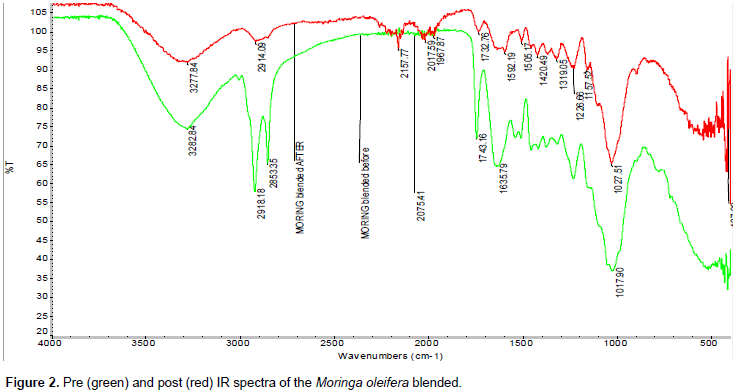

Figure 2 shows absorption at 3282.84 cm-1 in blended M. oleifera sample due to OH stretching vibration (Kumar and Tamilarasan, 2013; Zhang et al., 2013; Sivaraj et al., 2001). The band at 2918.18 and 2853.36 cm-1 is due to C-H stretching. The absorption at 1743.18 cm-1 could be C=O (carbonyl) stretch and 1635.79 cm-1 is due to C=C stretching (Lee et al., 2007). The adsorption peaks at 1246.00 and 1017.90 cm-1 can be assigned to C-O group of an acid and an ester, respectively (Sharma and Uma Gode, 2010). The blended M. oleifera loaded with Pb2+ shows the absorption peak at 3282.98 cm-1 lost intensity and shift to 3277.84 cm-1. This could be the stretching of the OH group under the influence of adsorbed Pb2+. It shows the absorption peaks at 2918.18 and 2853.36 cm-1 lost their intensity and shifted to 2914.08 and 2843.06 cm-1, because of the C-H stretching.

Absorption peak 1743.18 cm-1 lost intensity and shifted to 1732.78 cm-1. The repeated shift due to the C-O and OH stretching suggests that both C-O and OH functional groups are involved in the binding or reacting with Pb2+.Figure 3 shows absorption at 3282.83 cm-1 in seeds is due to OH stretching vibration (Kumar and Tamilarasan, 2013; Zhang et al., 2013; Sivaraj et al., 2001). The band at 2918.13 and 2841.24 cm-1 is due to C-H stretching. The absorption at 1743.33 cm-1 could be C=O (carbonyl) stretch and 1635.39 cm-1 is due to C=C stretching stretching (Lee et al., 2007).

M. oleifera seeds loaded with Pb2+ show the absorption peak at 3282.83 cm-1 lost intensity and shifted due to the stretching of the OH group.

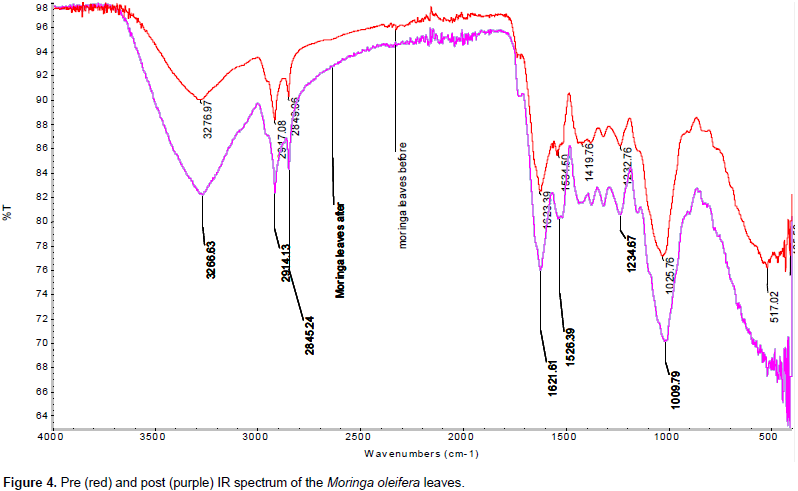

It shows the absorption peaks at 2918.13 cm-1 and 2841.24 cm-1 lost their intensity and shifted because of the C-H stretching. Absorption peak at 1743.33 cm-1 lost intensity and shifted to 1730 cm-1 due to C=O lead absorption. Figure 4 shows absorption at 3266.63 cm-1 in leaves is due to OH stretching vibration (Kumar and Tamilarasan, 2013; Zhang et al., 2013; Sivaraj et al., 2001). The band at 2914.13 and 2849.06 cm-1 is due to C-H stretching. The absorption at 1621.61 cm-1 could be C=O (carbonyl) stretch and 1528.39 cm-1 is due to C=C stretching (Lee et al., 2007). The adsorption peaks at 1234.67 and 1009.79 cm-1 can be assigned to C-O group of an acid and an ester, respectively (Sharma and Uma Gode, 2010).

M. oleifera leaves loaded with Pb2+ show the absorption peak at 3266.63 cm-1 lost intensity and shifted to 3276.97 cm-1 due to stretching of the OH group under the influence of Pb2+ adsorption. It shows the absorption peaks at 2914.13 and 2846.24 cm-1 lost their intensity and shifted to 2917.08 and 2843.06 cm-1, respectively, because of the C-H stretching. Absorption peak at 1621.81 cm-1 lost intensity and shifted to 1623.38 cm-1. The repeated shift due to the C-O stretching suggests that C-O might be a functional group that Pb2+ can bind and react with it. The obtained results are in agreement with those of Al-Dujaili et al. (2013), with some differences and this might be as a result of different source of M. oleifera leaves.

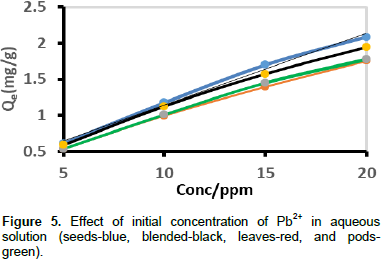

Effect of initial concentration of Pb2+ in aqueous solution

In all the biosobent samples, adsorption capacity increased with increase in initial metal ion concentration. This is due to higher interaction between the metal ion and the adsorption site (Farhan et al., 2012). This trend suggests that increase in adsorbate concentration results in increase in number of available molecules per binding site of the adsorbent, thus bringing about a higher probability of binding of molecules to the adsorbent. Figure 5 shows that the equilibrium concentrations increased with increase in initial concentration of Pb2+.

The amount of Pb2+ absorbed by moringa seeds, blended, leaves and pods at equilibrium (Qe) increased from 0.611 to 2.086 mg/g, 0.5884 to 1.9429 mg/g, 0.5348 to 1.7525 mg/g, and 0.5358 to 1.7755 mg/g, respectively, as the initial concentration was increased from 5 to 20 mg/L. The initial concentration provides an important driving to overcome all mass transfer resistances of the Pb2+ between the aqueous and solid phases. Hence, a higher initial concentration of Pb2+ ions will enhance the sorption process. The Pb2+ removal efficiency decreased from 97.79 to 83.44% for M. oleifera seeds, 85.58 to 70.1% for leaves, 85.74 to 71.02% for pods, and 94.15 to 77.72% for the M. oleifera blended as the lead concentration was increased from 5 to 20 mg/L. The results show that the moringa seeds have greater sorption capacity, however, blended samples have a comparable sorption efficiency.

Effect of adsorbent dosage

The results show that the effects of adsorbent dosage on adsorption are as shown in Figure 6. Percentage removal increased with increase in dosage up to 0.9 g. The optimum percentage removal for seeds was 98.7%, the blend was 95.85%, leaves was 92.19%, and for the pods was 89.78%. After the optimum dosage, percentage removal becomes constant. However, no significant increment in the biosorption tendency was observed in further increasing the biomass dosage from 0.9 g onward for all the four different biosobent. This can be explained by the fact that at low dosage concentration, there is limited surface area for adsorption, an increase in dosage results in more adsorption sites. After the optimum dosage, active sites for adsorption become excess and the metal ions become limiting and sorption sites remain unoccupied. A direct proportionality relationship between the adsorbent dosage and percent adsorption was also observed when activated carbon prepared from cashew nut shells was used as the sorbent material (Tangjuank et al., 2009).

Effect of contact time

Percentage removal increased with increase in contact time for all the four biosorbent up to 60 min (Figure 7). From the adsorption experiment results at 60 min, the sorption efficiency of M. oleifera seeds was 96.66%, blend was 93.84%, pods was 88.75%, and leaves was 86.54%. After 60 min, the adsorbed quantities showed nearly no significant change. In the early stages, more number of vacant sites are available for adsorption. As contact time increases, the maximum number of sites that got adsorbed to the metal ions increases which becomes difficult for the metal ions to search for the very few remaining sites, thus rate of adsorption decreases in the later.

Effect of pH

Figure 8 shows the effect of pH on sorption efficiency of the different studied biosorbents. For all the three biosorbents, the removal efficiency increased with increase in pH. For M. oleifera seeds, it increased from 69 (pH 3) to 81% (pH 6) and 97% (pH 7). It increased from 67.4 (pH 3) to 78.83% (pH 6) and 92.49% (pH 7) for M. oleifera leaves. It increased from 68.35 (pH 3) to 79.34% (pH 6) and 92.94% (pH 7) for pods. It increased from 68.75 (pH 3) to 82.05% (pH 6) and 95.39% (pH 7) for moringa blend. For all the four biosorptions, there is a general decrease in biosorption from pH 7 to 8. At pH greater than the optimum, there was no significant change in sorption. At low pH, there is competition between H+ ions and metal ions since the H+ ions are in high concentration. They tend to protonate the active sites which inhibit the metal ions from binding to the active site. As pH is increased, negatively charged sites increase which result in greater electrostatic attractions (Nharingo et al., 2012). At higher pH, percentage removal is likely to be a result of precipitation of OH- ions which form complexes with Pb2+. A similar trend was also observed when papaya seeds were used for the removal of zinc (Ong et al., 2011).

Effect of temperature

The optimum temperature was observed at 40°C with metal removal of 98% for seeds biomass, 96% for moringa blended sample, 94% for pods and 89% for leaves biomass. The data presented in Figure 9 show that the adsorption of metal ions by M. oleifera seeds, leaves, pods and the blended biomass increased with increase in temperature which is typical for the biosorption of most metal ions from their solution (McKay et al., 1982). The magnitude of increase declines as temperature increased from 40 to 80°C. The slight decrease in biosorption with increase in temperature in all samples can be attributed to the attractive forces between biomass surface and the metal ions. The attractive forces at higher temperatures are likely to be weakened and the sorption decreases.

There were significant increases in sorption efficiency of seeds and blended from 25 to 40°C which were 86 to 98% and 89 to 96%, respectively. Results of the studied biosorbents suggest that Pb2+ removal processes from aqueous solutions is biphasic, that is, lower temperature phases (25 to 40°C) and the high temperature sorption process (40 to 80°C). Generally, there is rapid metal sorption process at the lower temperature phase. The sorption of metal ions at higher temperature phases (40 to 80°C) by all the biomasses were very low. At high temperature, the thickness of the boundary layer decreases due to the increased tendency of the metal ion to escape from the biomass surface to the solution phase, which results in a decrease in adsorption as temperature increases (Aksu and Kutsal, 1991).

Sorption isotherms

The purpose of the sorption isotherms is to reveal the specific relation between the equilibrium concentration of adsorbate in the bulk and the adsorbed amount at the surface. The isotherm results of Moringa oleifera samples biosorption on lead at a constant temperature of 25°C were analyzed using four important isotherms; the Langmuir, Freundlich, Temkin, and Dubinin–Redushkevich (D–R) isotherm models.

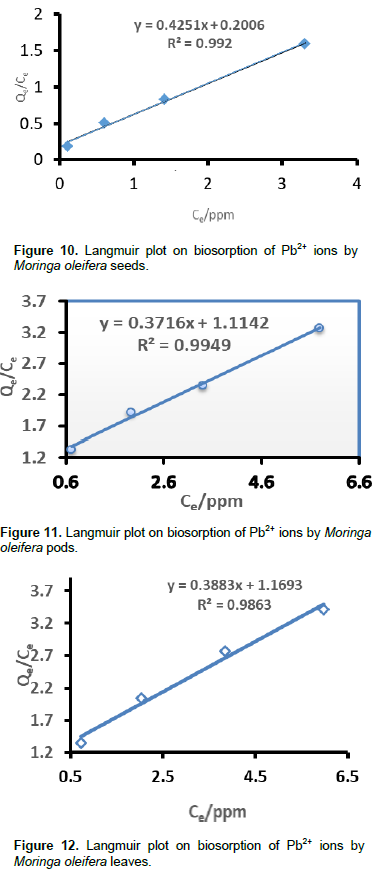

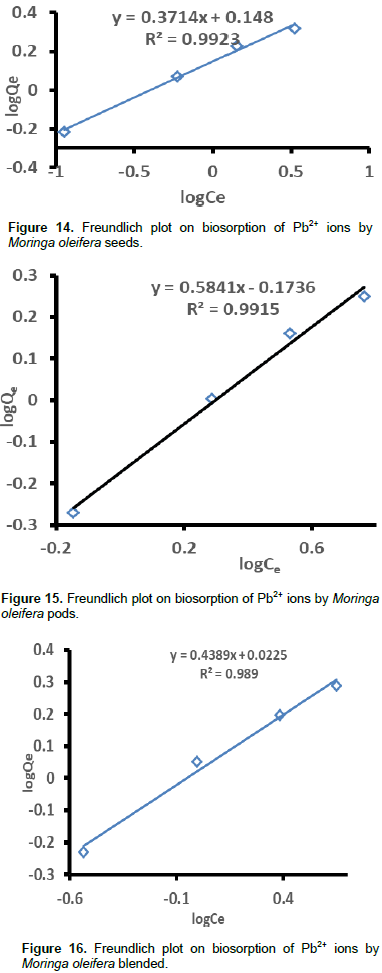

Langmuir isotherm

The linearized Langmuir Equation 2a was used to obtain the isotherm parameters.

Where, Qe is the milligrams of accumulated per gram of the biosorbent, Ce is the metal residual concentration in solution, Qm is the maximum uptake corresponding to the site saturation for a monolayer surface and b is the ratio of adsorption and desorption, that is, it indicates the affinity between adsorbent and the test analyte. A dimensionless Langmuir equilibrium constant (RL) shown in Equation 3.2b was also used to determine the shape of the isotherms.

Where, RL values between 0 and 1 show a favourable adsorption process, 0 indicates an irreversible adsorption, 1 indicates a linear adsorption and a value greater than 1 indicates an unfovourable adsorption process (McKay et al. 1982; Awwad and Salem, 2012). The RL values were calculated at different concentrations. The Langmuir plots for Pb2+ ions sorption using different samples of M. oleifera are shown in Figures 10 to 13. The RL values are shown in Table 1 and they are within the range of 0 to 1. This shows that the Pb2+ biosorption processes were favorable for all M. oleifera biosobent (McKay et al., 1982; Awwad and Salem, 2012). The RL values decreased with an increase in concentration in all M. oleifera samples. In M. oleifera seeds, the values of RL were small as compared to all samples at the same concentration and the RL values were approaching zero with increase in initial concentration which suggest irreversible adsorption with increase in concentration. The Langmuir constants (Qm and b) were determined from the slope and intercept of the Langmuir plot and are presented in Table 2.The correlation coefficients for lead sorption using M. oleifera seeds (0.9920), blended (0.9967), pods (0.9949) and leaves (0.9863) are shown in Table 2

They all fit the Langmuir isotherm which indicates good monolayer coverage on the surface of all the biosobents. The saturated monolayer sorption capacity, Qm is a function of many parameters such as pH and temperature, it provides a good measure for comparing the efficiency of different sorbents in removing a given metal. The sorption capacity, Qm which is a measure of the maximum adsorption capacity corresponding to complete monolayer coverage showed that the M. oleifera samples had a mass capacity for Pb2+ in this order: blended (3.0989 m/g) > pods (2.9984 mg/g) > leaves (2,5753 mg/g > seeds (2.3524 mg/g). These values are higher than those obtained in other studies for Pb2+ adsorption (Aziz et al., 2016). The order of moringa maximum sorption capacity proved that the blended sample has better sorption capacity at 25°C. The b-values for seeds, blended, pods and leaves were 2.1191, 0.8979, 0.3453, and 0.3321, respectively. The positive values of b show that the biosorption of Pb2+ by M. oleifera samples was endothermic (Deng et al., 2008).

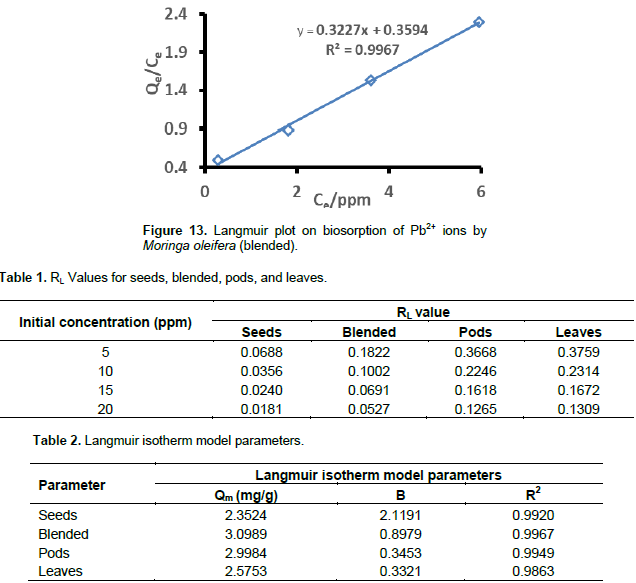

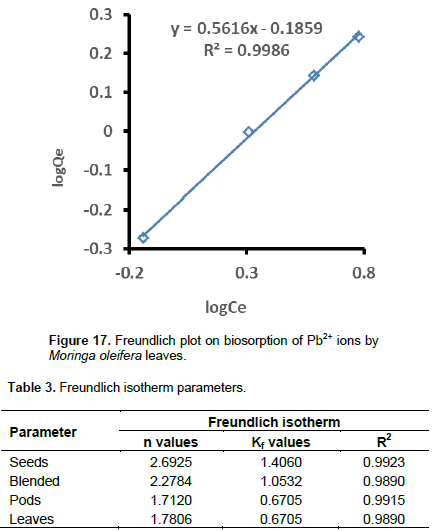

Freundlich isotherm

The linear form of the Freundlich isotherm Equation 3 was used to estimate the adsorption intensity of the sorbent towards the adsorbate. It assumes that the adsorption process takes place on a heterogeneous surface of adsorption capacity.

Where, Qe is the metal uptake at equilibrium concentration (ppm), Ce is the equilibrium metal ion concentration (ppm), KF is the Freudlich’s constant of adsorption capacity and n is the constant of adsorption. KF was estimated from the y-intercept and n was calculated from the slope. Plots for the determination of Freundlich isotherm parameters are presented in Figures 14 to 17. The Freundlich isotherm parameters (R2, KF, and n) extracted from Figures 14 to 17 are shown in Table 3. Low values of KF indicate minimal adsorption (Ashraf et al., 2012).

According to KF values, the order of ascending adsorption was seeds (2.6925)> blended (2.2784)> leaves (1.78)> pods (1.7120). The n-values should be in the range 1˂n˂10 to satisfy the heterogeneity condition (Farhan et al., 2012). This also implies a beneficial adsorption process. The n-values for all the moringa samples on Pb2+ sorption fall in this range, therefore, the surfaces are heterogeneous. The n-values are greater than 1 which shows that the adsorptions were mainly physical processes for all the samples (Farhan et al., 2012). According to n-values in Table 3, the order of heterogeneity was increasing in the order: seeds (2.6925)>blended (2.2784)>leaves (1, 7806)>pods (1.712). Analysis of the n-values in Table 3 also shows that adsorption of Pb2+ into moringa seeds, blended, pods and leaves much favored physical adsorption process on Pb.

Adsorption capacity on seeds and blended sample was likely to promote new chemical bonds at the biomass’s surface which might lead to the enhancement of the biomass adsorption capacity. This reasoning could explain the cause of the increase of removal efficiency with the increase of initial Pb2+ concentration and the higher values of KF (adsorption capacity) on moringa seeds and blended sample compared to moringa leaves and pods. However, physical adsorption was shown to be favorable for adsorption of Pb2+ by all the biomas samples. In some studies, Pb2+ ions adsorption has been reported to favour chemisorption (Aziz et al., 2016). This can be attributed to different sources of the M. oleifera plant in which different geographical location and climatic conditions can affect the chemical composition of the biosorbent.

Dubinin-Radushkevich (D-R) isotherm

The D-R isotherm model was applied to the data in order to deduce the heterogeneity of the surface energies of adsorption and the characteristic porosity of the adsorbent. The linear form of the D-R isotherm is given in Equation 4a:

Where, qD is the amount of lead adsorbed per unit dosage of M. oleifera samples (mol/g), qe is the theoretical monolayer sorption capacity (mol/g), BD is the constant of the sorption energy (mol2/J2), which is related to the average energy of sorption per mole of the adsorbate as it is transferred to the surface of the solid from infinite distance in the solution (Dubinin et al., 1947), T is the solution temperature (K) and R is the gas constant. The value of mean sorption energy (apparent energy of adsorption), E (kJ/mol), was calculated from D-R parameter according the relationship represented in Equation 4b:

The value of mean sorption energy gives information about chemical and physical sorption. The E value ranges from 1 to 8 kJ/mol for physical sorption and from 8 to 16 kJ/mol for chemical sorption (Zheng et al., 2008). The D-R plots (lnQe against [RTln (1+1/Ce)]2) for the determination of D-R isotherm parameters are presented in Figures 18 to 21. The D-R isotherm parameters are shown in Table 4. The maximum sorption capacity of lead ions on moringa samples (qD) was in the order: moringa seeds (1.786 mol/g) > moringa blended (1.701 mol/g) > moringa pods (1.585 mol/g) > moringa leaves (1.525 mol/g) at 25°C. The E-value (4.082, 2.5, 1.581, and 1.525 KJ/mol) for moringa seeds, moringa blended, moringa pods, and moringa leaves, respectively. These were all found in the range of 1 to 8 kJ/mol, indicating that the type of sorption of Pb2+ on all moringa samples is essentially physical process.

Temkin isotherm

The Temkin model assumes that the heat adsorption of all molecules decreases linearly with coverage due to adsorbate-adsorbent interactions. Its linear form is expressed as shown in Equation 5.

Where,

in J/mol corresponding to the heat of adsorption, b

T is the Temkin isotherm constant, A is the equilibrium binding constant for the maximum binding energy. Plots for the determination of Temkin isotherm parameters are as shown in Figures 22 to 24. The constants

A and b

T were calculated from the intercept and slope of the Temkin plot and are listed in Table 5. For analysis of Temkin isotherm parameters in Table 6, equilibrium binding constant were in the order: seeds > blended > pods > leaves. The results reflected that the seeds have a greater binding constant and the blended sample yielding almost the same binding constant. The constant b

T values were 5638.53 (seeds), 5025.50 (blend), 4144.48 (pods) and 4383 J/mol (leaves). This is an indication of the heat of sorption indicating a physical adsorption.

Kinetic study of Pb2+ adsorption

The pseudo-first order and pseudo-second order kinetic models were used to investigate mechanisms of Pb2+ ions onto different parts of M. oleifera plant. Lagergren proposed a pseudo first order kinetic model represented in Equation 6.

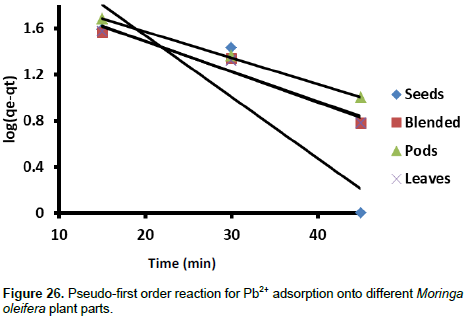

Where, qt and qe are adsorption capacity at time t and at equilibrium, respectively, and kad is the pseudo-first order rate constant of adsorption. The linear plot of log(qe-qt) vs. t (Figure 26) was used to estimate the rate constant and correlation coefficients for Pb2+ adsorption. The pseudo-second order reaction parameters were estimated using the Equation 7.

Where, h = kqe2 (mg g-1 min-1 and k = rate constant for pseudo-second order adsorption mechanism. The linear plot of t/qt vs. t (Figure 27) was used to estimate the pseudo-second order rate constants and correlation coefficients for Pb2+ adsorption. These parameters are summarised in Table 6. The highest rate constant for the pseudo-first order kinetic model was obtained from the seeds. The blended sample gave the highest rate constant for the pseudo-second order kinetic model. The correlation coefficients are generally low for both kinetic models although the pseudo-second order kinetic model gave relatively higher values. Such low values can be attributed to more physical adsorption interactions than chemisorption.

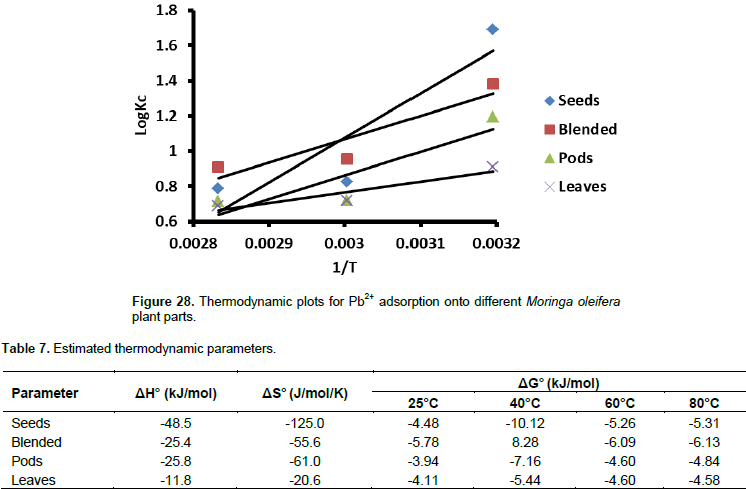

Estimation of Gibbs free energy (ΔG°), enthalpy (ΔH°), and entropy (ΔS°) for Pb2+ adsorption

These thermodynamic parameters were evaluated using Equation 8a to c.

Where, Kc = equilibrium rate constant, Cesp = solid phase concentration at equilibrium (mg/L), Ce = equilibrium concentration in solution (mg/L), and ΔG°, ΔH°, ΔS° are changes in Gibbs free energy (kJ/mol), enthalpy (kJ/mol), and entropy (J/mol/K). A linear plot of logKC vs. 1/T (Figure 28) was used to estimate ΔH0 and ΔS0 for Pb2+ adsorption on M. oleifera plant parts. The thermodynamic parameters are summarised in Table 7. ΔG° values for all adsorbents were negative (Table 7), indicating that the adsorption process is feasible and spontaneous. The seeds have shown an enhanced feasibility of Pb2+ adsorption at 40°C, however this decreased at higher temperatures. The blended sample also has comparable adsorption feasibility. The ΔG° values for all samples were less than -20 kJ/mol, indicating physical adsorption as the main interaction between Pb2+ and all the adsorbents. However, in another study by Adebisi et al. (2016), ΔG° values for Pb2+ adsorption using activated carbon from palm oil mint effluent were positive hence less spontaneous. This shows that spontaneity of lead adsorption depends so much on type of biomass. The ΔH° values in this study were all negative, indicating the exothermicity of the adsorption process. The ΔS0 values revealed that the randomness of the adsorption process was more pronounced with the seeds (-125.0 kJ/mol).

in J/mol corresponding to the heat of adsorption, bT is the Temkin isotherm constant, A is the equilibrium binding constant for the maximum binding energy. Plots for the determination of Temkin isotherm parameters are as shown in Figures 22 to 24. The constants A and bT were calculated from the intercept and slope of the Temkin plot and are listed in Table 5. For analysis of Temkin isotherm parameters in Table 6, equilibrium binding constant were in the order: seeds > blended > pods > leaves. The results reflected that the seeds have a greater binding constant and the blended sample yielding almost the same binding constant. The constant bT values were 5638.53 (seeds), 5025.50 (blend), 4144.48 (pods) and 4383 J/mol (leaves). This is an indication of the heat of sorption indicating a physical adsorption.

in J/mol corresponding to the heat of adsorption, bT is the Temkin isotherm constant, A is the equilibrium binding constant for the maximum binding energy. Plots for the determination of Temkin isotherm parameters are as shown in Figures 22 to 24. The constants A and bT were calculated from the intercept and slope of the Temkin plot and are listed in Table 5. For analysis of Temkin isotherm parameters in Table 6, equilibrium binding constant were in the order: seeds > blended > pods > leaves. The results reflected that the seeds have a greater binding constant and the blended sample yielding almost the same binding constant. The constant bT values were 5638.53 (seeds), 5025.50 (blend), 4144.48 (pods) and 4383 J/mol (leaves). This is an indication of the heat of sorption indicating a physical adsorption.