ABSTRACT

In this study, untreated Tectona grandis (UTG) and citric acid- modified T. grandis (CAMTG) bark powder were used for the adsorption of Cu (II) ions from aqueous solution. The UTG and CAMTG were characterized by Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR), and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The adsorption characteristics were carried out by determining the solution pH, initial concentration of Cu (II) ions, effect of time and temperature. Langmuir, Freundlich and Temkin isotherms were used to describe the equilibrium model with Freundlich isotherm giving the best fit. The maximum monolayer adsorption capacity for CAMTG was higher than that of UTG. Also, there was about a four-fold increase in the adsorption of Cu(II) ions by CAMTG (Ao = 87.0 mg/g) over UTG (Ao = 22.9 mg/g). The kinetic data were explained by employing the pseudo-first and pseudo-second order models. The pseudo-second order kinetic model has an outstanding suitability to the experimental data. The positive enthalpy and negative free energy are indications of the endothermic and spontaneous nature of the copper (II) ion adsorption process. CAMTG is therefore, a more viable adsorbent for the removal of Cu(II) ions from aqueous solution than UTG.

Key words: Adsorption, copper, equilibrium, kinetics, Tectona grandis.

The increased rate at which heavy metals such as copper are released into the environment in the 21st century has raised serious health concerns all over the world. The rapid and dangerous increase in the level of these heavy metals in the environment is due to the nonchalant attitudes to environmental safety by some industries involved in their production. Culpable industries in this respect are those of metallurgical, galvanizing, metal finishing, electroplating, mining, power regeneration, electronic devices manufacturing and tannery (Ajaelu et al., 2017). Copper toxicity, for instance, has been implicated in health related issues, among which are hyperactivity in children, depression, migraine, extreme tiredness, anorexia, premenstrual syndrome, depression, anxiety and learning disorder. Some of the methods for separation and recovery of heavy metals are ion exchange, chemical precipitation, electrocoagulation (Akyol, 2012), evaporation and membrane processes (Wang and Chen, 2009) which are used on a large scale. However, these procedures are inadequate and uneconomical when metal ions exist in relatively low concentrations (Bhatti et al., 2007). They also generate large quantities of toxic sludge and secondary pollutants thereby requiring the use of large amount of reagents (Yadava et al., 2010). The removal of toxic heavy metals from industrial wastewaters using conventional chemical approaches like adsorption, oxidation and reduction and chemical precipitation, among others (Yadav, 2010), proved to be not cost effective. Similarly, activated carbon which has been employed to reduce the amount of heavy metal to harmless level due to its operational simplicity and reuse potential (Anupam et al., 2011) remains an expensive material (Mohanty, 2005). However, in recent years, the use of plant materials for the removal of heavy metal has become a more acceptable method because it has the ability to cause a reduction in the quantities of heavy metal even at low concentrations. Biosorbents that have been adopted for reducing to harmless level the heavy metals in the environment include Senna alata (Ajaelu et al., 2017), sawdust (Vaishya and Prasad, 1991), grape stalks (Villaescusa et al., 2004), carrot residue (Nasernejad et al., 2005), Ethiopian pepper (Ajaelu et al., 2011), groundnut shells (Shukla and Pai, 2005), wild herbs (Al-Senanai and Al-Fawzan, 2018), rice shell (Aydin et al., 2007) and wine making waste (Alguacil et al., 2018). Also, our preliminary investigations revealed that T. grandis was effectual in the reduction of cadmium ions level from waste water (Ajaelu et al. 2013). Tectona grandis (teak) is a member of the Lamiaceae family. It is a large deciduous tree that is dominant in mixed hard wood forest reaching over 30 m in height in favorable conditions (Orwa et al., 2009). The plant is readily available locally.

This study, therefore, investigated the effectiveness of T. grandis (UTG) as an adsorbent for reducing the amount of Cu2+ ions in solutions. Two forms of the plant material –untreated T. grandis (UTG) and citric acid modified T. grandis (CAMTG) were tested. Characterization of UTG and CAMTG was done with SEM and FTIR. Equilibrium studies were explained by Langmuir, Freundlich and Temkin models. The kinetic studies were elucidated using Pseudo-first order and pseudo-second order models. Thermodynamic parameters such as free energy, entropy and enthalpy were also determined for the adsorptive reduction in the level of Cu2+ ions by UTG and CAMTG.

All reagents used are of analytical grade. Citric acid monohydrate (CA) (Figure 1) was used in the chemical modification of the biomass. Stock solution of 1000 mgL−1 of Cu2+ from Cu(NO3)2 salt was prepared. Solutions with concentrations ranging from 20 to 100 mgL−1 of Cu2+ ions were prepared by appropriate dilution of the stock solution immediately prior to their use. The T. grandis biomass was obtained from a wetland situated at Iwo, Nigeria (7° 38” 01ʹ N, 4° 11” 01ʹ E). After harvest, the biomass was washed several times with deionized water to remove the dust particles, and then dried in an oven at 373K for 24 h. The dried biomass was crushed by a high speed electric grinder. The particles were sieved with a 500-μm mesh size and stored in a plastic bag.

Citric acid modification

The chemical modification of T. grandis was similar to that already described by Vaughan et al., (2001) with little modifications. 0.2 M CA was added to UTG in the ratio of 12:1 (CA: UTG, w/v) and stirred for 45 min. The oven at 50°C was used to dry the UTG/acid mixture for 2 h. This was followed by increasing the temperature of the oven to 120°C to ensure thermochemical reaction of the mixture. The dry mixture was then cooled at room temperature, after which 0.1 M NaOH was added and agitated for 1 h to neutralize any residual acid present. The CA modified T. grandis (CAMTG) was then washed severely with de-ionized water to remove the residual alkali. The wet CAMTG was dried in an oven at 105°C until constant weight and stored in a stoppered plastic tube.

Instrumental characterization of UTG and CAMTG

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrophotometer, Agilent Technologies Cary 630FTIR spectrometer, was used for functional group determinations on the surface of UTG and CAMTG. A sample press, which is a portion of the ATR interface, was employed to make certain that the UTG and CAMTG were in good contact with the surface of the sensor. A region of 4,000–650 cm–1 at 4 cm–1 resolution were employed to collect the data. The surface morphologies of UTG and CAMTG were determined with scanning electron microscope (Zeiss Auriga HRSEM).

Adsorption of Safranin O

Equilibrium adsorption was determined as previously described (Ajaelu et al., 2017). In brief, batch adsorption experiments were carried out by contacting 0.5 g of CAMTG (and UTG) with 20 mL of copper solution pH in a 250-mL beaker. The samples in the beakers were then agitated on an electric shaker at 298 K with a speed of 250 rpm until equilibrium was attained. Thereafter, the mixture was filtered and the concentrations of the residual Safranin O were determined using atomic absorption spectrophotometer (PG 990, PG Instruments, Britain). The amount of Cu2+ adsorbed, qe (mg/g) (Equation 1) and the corresponding removal percentage (%) (Equation 2) can be calculated by the following equations:

Characterization of UTG and CAMTG

The textures of the external surfaces and morphology of UTG and CAMTG were observed by SEM as reflected in Figures 2a and 2b respectively. The UTG surface was irregular in shape and has some pores. After modification, a noticeable change was observed in the structure of CAMTG. It has broken surfaces with pores. UTG and CAMTG FTIR spectra are reflected in Figures 3a and b. The absorption at 3278 cm -1 for UTG corresponds to OH which was shifted to 3338.7 cm -1 in CAMTG after the addition of Cu2+ ion (Patel et al., 2007). The bands at 2920.4 cm-1 for UTG and 2818.6 cm-1 for CAMTG were associated with the presence of asymmetric -CH2 and symmetric vibration of CH2 group respectively. The bands at 1720.2 cm-1 for UTG and 1733.2 cm-1 for CAMTG represents C=O vibration of carboxylic acid. UTG shows an absorption band at 1620.1 cm-1 identified as N-H bend of amine (-NH2). This was shifted to 1541.3 cm-1 in CAMTG after the sorption of copper (II) ion. The OH-bend of carboxylic acid on CAMTG was identified at 1438.8 cm-1. The –CH3 bend of alkane of CAMTG was located at 1369.8 cm-1. The C-O stretching vibration of COOH of UTG was identified at 1309.8 cm-1 which was shifted to 1317.6 cm-1 after the sorption of copper (II) ion in CAMTG. The peak at 1238 cm-1 for UTG is characteristic of a C-O stretch of carboxylic acid and was shifted to 1241.2 cm-1 in CAMTG. The peaks at 1181.8 and 1026 cm-1 for UTG were assigned to the C-F stretch of alkyl halide; but were shifted to 1157.3 and 1030.6 cm-1 respectively, in CAMTG.

Where NA is the Avogadro’s number, X and M are the cross-sectional area in m2/g and the molar mass in g of the adsorbate respectively (Ali et al., 2013). The calculation of specific surface area is based on the Ao value, the atomic mass of copper, 63.5 g, and its cross-sectional area of 1.58 Å2 (the radius of Cu2+ ions for close packed monolayer is 0.71 Å). The specific surface area of UTG for Cu2+ removal was 5.42 m2/g while that of CAMTG was 20.6 m2/g. Thus, CAMTG has wider surface area as compared to UTG which was responsible for its effectiveness in removing more Cu2+ ions from solution.

Effect of pH

The solution pH has impactful effect on the adsorption of Cu2+ on CAMTG than on UTG. From the experimental results reflected in the graph in Figure 4, it was observed that for CAMTG, there was a significant increase in adsorption from pH 2 to 7, a sharp increase from pH 6 - 7 and then a decrease. Adsorption of Cu2+ ions by CAMTG was better at slightly acidic to neutral pH condition than for basic environment. This is because as the pH increases from acidic to neutral pH the number of negatively charged sites increases, and adsorption of Cu on CAMTG consequently increased. These may also be due to the chemical reaction and strong electrostatic interaction of the surface of CAMTG as well as Cu2+ ions in solution.

UTG increased slightly with pH due to weak surface - Cu (II) ions electrostatic interaction. Thus, pH had more profound effect on CAMTG than on UTG. Similar results were obtained by some researchers (Hameed and El-Khaiary, 2008; Adebowale et al., 2014). Moreover, at lower acidic pHs the charges on the surfaces of UTG and CAMTG are positive due to the next protonation reactions of the hydroxylic sites (1):

As the pH increases, the adsorbent acidic sites were deprotonated owing to the surface that were negatively charged:

The surfaces of UTG and CAMTG are represented by ≈Z. Vasconcelos et al., (2008) and Tong et al. (2011) got identical results.

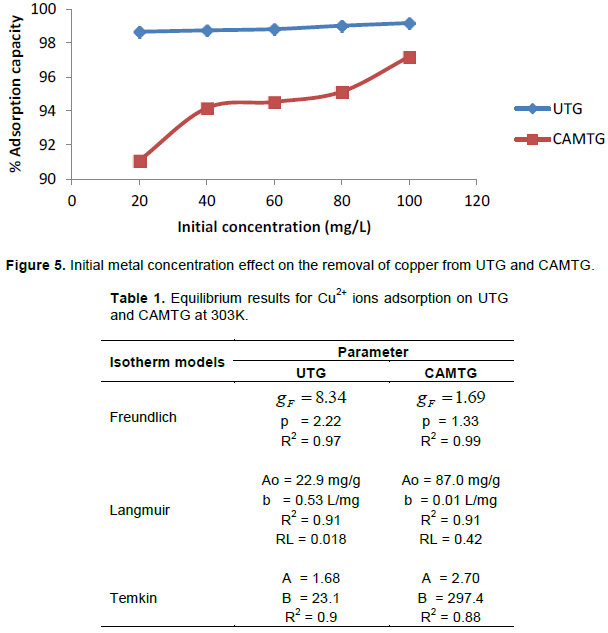

Effect of initial metal concentration

The initial concentration of the metal affects the uptake capacity of CAMTG and UTG to adsorb Cu2+ ions as shown in Figure 5. The sorption capacity of CAMTG for Cu2+ ions rose sharply with initial Cu2+ concentration from 20 to 40 mg/L and then increased gradually from 40 to 80 mg/L. UTG sorption capacity increased slightly with initial Cu2+ concentrations from 20 to 100 mg/L.

Adsorption isotherm

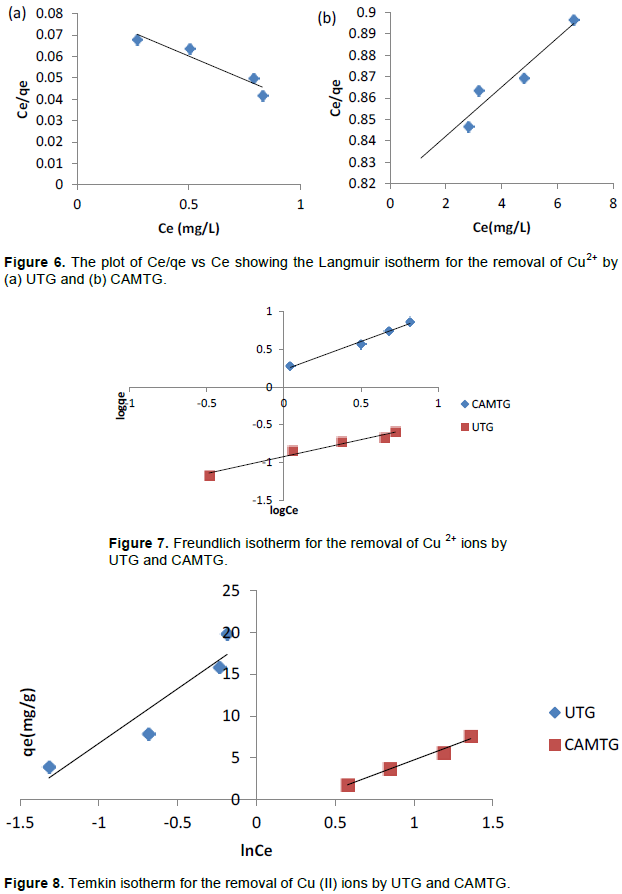

The parameters of the adsorption isotherms are reflected in Table 1. Experimental equilibrium results show that Freundlich isotherms (Figure 7) for both UTG and CAMTG (UTG, R2 = 0.97 and CAMTG, R2 = 0.99) fitted best when compared to that of Langmuir in Figure 6 (UTG, R2 = 0.91 and CAMTG, R2 = 0.91) and Temkin in Figure 8 (UTG, R2 = 0.91 and CAMTG, R2 = 0.88).

Freundlich isotherm fitted better for CAMTG (R2 = 0.99) than for UTG (R2 = 0.97). In addition, the values of n are greater than unity for both UTG and CAMTG which indicate that the values of n are greater than unity for both UTG and CAMTG which implied the favorability and intensity of adsorption of Cu2+ ions on the surfaces of both UTG and CAMTG. The Langmuir maximum adsorption capacity of CAMTG (87.0 mg/g) is higher than that of UTG (22.9 mg/g). This is an increase of about four-fold in Cu2+ ions adsorption by CAMTG over UTG, implying that the citric acid modification of the untreated T. grandis increased the number of active sites available for adsorption, and consequently enhance the electrostatic interaction between Cu2+ ions and CAMTG. Langmuir isotherm efficiency can also be buttressed by determining whether the adsorption is favourable or not, using the separation factor, RL, also known as the dimensionless equilibrium parameter. Both UTG (RL = 0.02) and CAMTG (RL = 0.42) have RL<1. Thus the sorption of Cu2+ ions on both UTG and CAMTG is favourable.

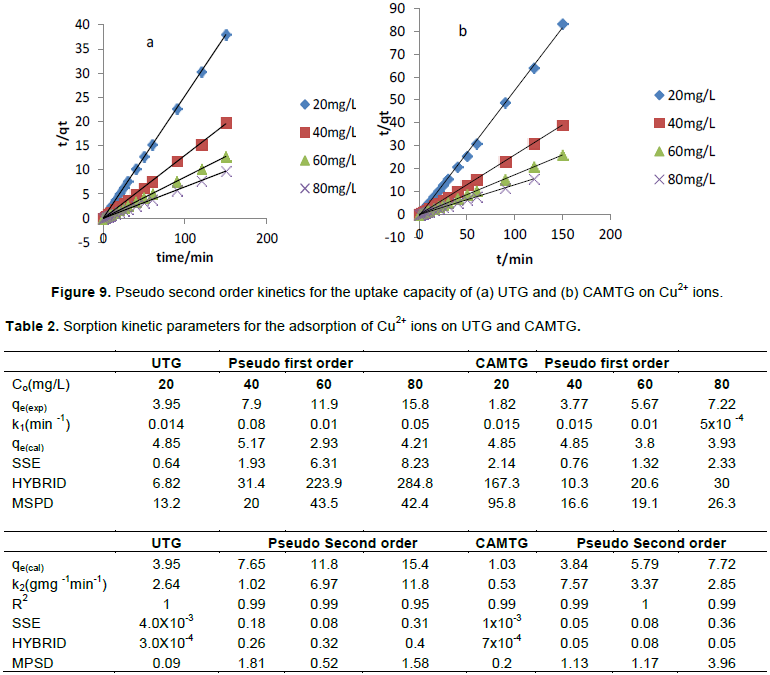

Effect of adsorption kinetics

The kinetic plots of pseudo-second order reaction is presented in Figure 9. The pseudo-first order kinetic plot gave a poor fit and, therefore, cannot be used to explain the sorption of Cu2+ ions on both UTG and CAMTG. The kinetic results are presented in Table 2. The calculated values of sorption capacity using Equation 9 which is reflected in Table 2 for a pseudo-second order kinetic gave strong agreement with the experimental values (qexp), and excellent results for the correlation coefficients were obtained. There was increase in the values of qcalc as the concentration rose from 20 to 80 mg/L for both UTG and CAMTG. Thus, pseudo-second order kinetic model was preferred in describing the Cu2+ sorption onto UTG and CAMTG.

Moreover, only the pseudo-second order model, in which the metal binding capacity is assumed proportional to the number of active sites occupying the sorbents (UTG and CAMTG), gave a good representation of the sorption rate (Ajaelu et al., 2017; Ferreira et al., 2011).

Error Equations 10, 11 and 12 were used to describe the appropriateness of the kinetic models for the sorption of Cu2+ ions on UTG and CAMTG. The model fits well if the error value is minimized. Table 2 showed that the SSE, HYBRID and MPSD values obtained for UTG and CAMTG were lower for pseudo-second order kinetic than for pseudo-first order kinetic models. This, of a certainty, showed that pseudo second order kinetic model described better the sorption of Cu2+ ions on UTG and CAMTG.

Thermodynamic effect

To study the effect of temperature, experiments were carried out at different temperatures of 303, 308, 313 and 328K and different concentrations of 20, 40, 60 and 80 mg/L, respectively. It was observed that temperature has a greater effect on CAMTG than on UTG. Moreover, at a particular temperature, concentration increase enhances the quantity of Cu2+ ions adsorbed on the surfaces of both UTG and CAMTG.

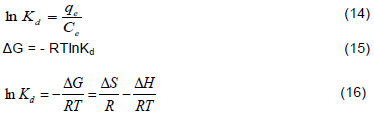

The thermodynamic parameters were obtained from the following equations:

Where Kd, is the ratio of Cu2+ ions adsorbed at equilibrium to that left in the solution at equilibrium. R is the universal gas constant in J mol -1K -1, T is the absolute temperature in K, ΔG (kJmol -1) is the Gibbs free energy of adsorption, ΔH is the enthalpy change (kJmol -1) while ΔS (Jmol -1K -1) is the entropy change. The various values of ΔH and ΔS were obtained from the slopes and intercepts of the plot of lnKd against 1/T (as presented in Figures 10a and b) at different Cu2+ ions concentrations of 20 to 80 mg/L and the results are listed in Table 3. It is evident from Table 3 that the sorption of Cu2+ ions on both UTG and CAMTG are endothermic and spontaneous as reflected in the positive values of ΔH and the negative values of ΔG. Thus, high temperatures enhanced the dehydration procedure and therefore, the adsorption process. Similar results were obtained by Gupta and Sharma (2002), and Chen and Wang (2006). The enthalpy changes necessary to accomplish the adsorption process was lower for CAMTG (9.23-25.6 kJ mol-1) than for UTG (3.62-34.5 kJ mol-1). This may be due to the existence of additional available pores for sorption in CAMTG than in UTG. The values of ΔG for both UTG and CAMTG are negative, which are indications that the sorption processes were spontaneous. ΔS was also an indication of the good affinity of adsorbent for adsorbate and increased randomness during the adsorption process (Ajaelu et al., 2017). In addition, the positive value of the entropy ΔS indicated that the increasing entropy, as a result of solvent desorption, was higher than reduction of entropy caused by solute adsorption ((Vaishya and Prasad, 1991).

Table 4 shows the comparison of adsorption capacities for various adsorbents at different temperatures. It is obvious that CAMTG adsorbed best among all the other adsorbents.

This study examined the interaction of Cu (II) ion with the surface of untreated (UTG) and citric acid modified T. grandis (CAMTG) leaves powder. The effect of pH on the adsorption of Cu (II) by CAMTG was more pronounced than that of UTG. The surface area of CAMTG was about four-fold that of UTG. Consequently, the ratio of maximum monolayer adsorption of CAMTG to UTG is 4:1. Strong electrostatic interaction between Cu (II) ions and the adsorbents enabled pseudo-second order kinetic model to appropriately describe the adsorption of Cu (II) ions on both UTG and CAMTG at different concentrations of Cu (II) ions. Thermodynamic parameters determined showed that the metal adsorption process was endothermic and spontaneous. Citric acid modified T. grandis can be deployed to effectively reduce the amount of Cu (II) ions from aqueous solution.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Adebowale KO, Olu-Owolabi BI, Chigbundu EC (2014). Removal of Safranin O from aqueous solution by adsorption onto Kaolinite clay. Journal of Encapsulation and Adsorption Science 4:89-104.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Ajaelu CJ (2013). Kinetics and equilibrium studies of cadmium (II) ions adsorption onto Tectona grandis (Teak Plant) seed. Proceedings of the 36th Annual International Conference of the Chemical Society of Nigeria 1:461-473.

|

|

|

|

|

Ajaelu CJ, Dawodu MO, Faboro EO, Ayanda OS (2017). Copper Biosorption by Untreated and Citric Acid Modified Senna alata Leaf Biomass in a Batch System: Kinetics, Equilibrium and Thermodynamics Studies. Physical Chemistry 7(2):31-41.

|

|

|

|

|

Ajaelu CJ, Ikotun AA, Olutona OO, Ibironke OL (2011). Biosorption of aqueous solution of lead on Xylopia aethiopica. Journal of Applied Science in Environmental. Sanitation 6(3):269-277.

|

|

|

|

|

Akyol A (2012). Treatment of paint manufacturing wastewater by electrocoagulation. Desalination 285:91-99.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Alguacil FJ, Alcaraz L, Garcia-Diaz I, Lopez FO (2018). Removal of Pb2+ from waste water via adsorption unto an activated carbon produced from wine making waste. Metal 697(8):1-15.

|

|

|

|

|

Al-senanai GM, Al-Fawzan FF (2018). Adsorption study of heavy metal ions from aqueous solution of nanoparticles of wild herbs. The Egyptian Journal of Aquatic Research 44(3):187-194

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ali SZ, Atha M, Farooq U, Salman M (2013). Insight into Equilibrium and Kinetics of the Binding of Cadmium Ions on Radiation - Modified Straw from Oryza sativa. Journal of Applied Chemistry pp. 1-12.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Anupam K, Dutta S, Bhattacharjee C, Datta S (2011). Adsorptive removal of chromium (IV) from aqueous solution over powdered activated carbon: Optimization through response surface methodology. Chemical. Engineering Journal 173:135-143.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Aydin H, Bulut Y, Yerlikaya C (2008). Removal of Cu (II) from aqueous solution by adsorption onto low-cost adsorbents. Journal of Environmental Management 87(1):37-45.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bhatti HN, Mumtaz B, Hanif MA, Nadeem R (2007). Removal of Zn(II) ions from aqueous solution using Moringa oleifera Lam. (horseradish tree) biomass. Process Biochemistry 42(4):547-553.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Chen CL, Wang XK (2006). Adsorption of Ni(II) from aqueous solution using oxidized multiwall carbon nanotubes Industrial. Engineering Chemical Research 45:9144-9149.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Chowdhury S, Saha PD (2011). Biosorption, kinetics, thermodynamics and isosteric heat of absorption of Cu(II) unto Tamarindus indica seed powder. Colloids and Surface B: Biosurfaces 88:697-705.

|

|

|

|

|

Ferreira LS, Rodrigue, MS, de Carvalho JCM, Lodi A, Finocchio E, Perego P, Converti P (2011). Adsorption of Ni2+, Zn2+ and Pb2+ onto dry biomass of Arthrospira (Spirulina) platensis and Chlorella vulgaris. I. Single metal systems. Chemical Engineering Journal 173:326-333.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Foo KY, Hameed BH (2010). Insight into the modeling of adsorption isotherm systems. Chemical Engineering Journal 156(1):2-10.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gupta VK, Sharma S (2002). Removal of cadmium and zinc from aqueous solution of red mud. Environmental Science Technology 36(16):3612-17

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gupta BN, Curran M, Hasan S, Ghosh TK (2009). Adsorption characteristics of Cu and Ni on Irish peat moss. Journal of Environmental Management 90(2):954-960.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hameed BH, El-Khaiary MI (2008). Sorption kinetics and isotherm studies of a cationic dye using agricultural waste: Broad bean peels. Journal of Hazardous Materials 154(1-3):639-648.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kumar KV, Porkodi K, Rocha F (2008). Isotherms and thermodynamics by linear and non-linear regression analysis for the sorption of methylene blue onto activated carbon: comparisons of various error functions. Journal of Hazardous Material 151(2-3):794-804.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lu S, Gibb SW (2008). Copper removal from waste water using spent-grain as biosorbent. Bioresource Technology 99(6):1509-1517.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mahamadi C, Chapeyama R (2011). Divalent metal ion removal form aqueous solution by acid-treated and garlic-treated Canna indica roots. Journal of Applied Science and Environmental Management 15(1):97-103.

|

|

|

|

|

Marquartt DW (1963). An algorithm for least square estimation of non-linear parameters. Journal of Social, Industrial and Applied Mathematics 11(2):431-441.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mohanty K (2005). Removal of Chromium (VI) from dilute aqueous solutions by activated carbon developed from Terminalia arjuna nuts activated with zinc chloride. Chemical Engineering Journal 60(11):3049-3059.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Nasernejad B, Zadeh TE, Pour BB, Bygi ME, Zamani A (2005). Comparison for biosorption modeling of heavy metals (Cr(III), Cu(II), Zn(II)) adsorption from wastewater by carrot residues. Process Biochemistry 40(3):1319-1322.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ng JCY, Cheung WH, Mckay G (2012). Equilibrium studies of the sorption of Cu (II) ions onto chitosan. Journal of Colloid Interface Science 255(1):64-74.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Orwa C, Mutua A, Kindt R, Jamnadass R, Anthony S (2009). Agroforestry Database: a tree reference and selection guide version 4.0. World Agroforestry Centre, Kenya.

|

|

|

|

|

Ozcan A, Ozcan AS, Tunali S, Akar T, Kiran I (2005). Determination of the equilibrium, kinetics and thermodynamic parameters of adsorption of Cu(II) ions on seeds of Capsicum annuum. Journal of Hazardous Materials 124(1-3):200-208.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Patel HA, Somani RS, Bajaj HC, Jasra RV (2007). Preparation and Characterization of Phosphonium Montmorillonite with Enhanced Thermal Stability. Applied Clay Science 35(3-4):194-200.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Shukla SR, Pai, RS (2005). Adsorption of Cu(II), Ni(II) and Zn(II) on dye loaded groundnut shells and sawdus Seperation. Purification Technology 43(1):1-8.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Temkin MI (1941). Adsorption equilibrium and the kinetics of processes on nonhomogeneous surfaces and in the interaction between adsorbed molecules. Zhurnal Fizicheskoi Khimii 15:296-332.

|

|

|

|

|

Tong KS, Kassim MJ, Azraa A (2011). Adsorption of Cu ions from its aqueous solution by a novel biosorbent Ncaria gambir: Equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Chemical Engineering Journal 170(1)145-153.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Vaishya RC, Prasad SC (1991). Adsorption of copper(II) on sawdust. Indian Journal of Environmental Protection 11(4):284-289.

|

|

|

|

|

Vasconcelos HL, Camargo TP, Gong-alves NS, Neves A, Laranjeira MCM, Fa’vere VT (2008). Chitosan crosslinked with a metal complexing agent: Synthesis, characterization and copper (II) ions adsorption. Reactive & Functional Polymers 68(8):572-579.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Vaughan T, Seo CW, Marshall WE (2001). Removal of selected metal ions from aqueous solution using modified corncobs. Bioresource Technology 78(2):133-139.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Villaescusa I, Fiol N, Martinez M, Miralles N, Poch J, Serarols J (2004). Removal of copper and nickel ions from aqueous solutions by grape stalks wastes. Water Resource 38(4):992-1002.

|

|

|

|

|

Wang JL, Chen C (2009). Biosorbents for heavy metals removal and their future: A review. Biotechnology Advancement 27(2):195-226.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Yadava NK, Sreekrishnanc TR, Satyad S, Bishnoib NR (2010). Removal of chromium and nickel from aqueous solution in constructed wetland: Mass balance, adsorption-desorption and FTIR study. Chemical Engineering Journal 160(1):122-128.

Crossref

|

|