ABSTRACT

This study investigates the performance of medium-sized family businesses – hereafter MSFBs – during the economic recession by comparing family and non-family firms, and correlating the organisational performance to the family ownership and firms’ solvency. An empirical research study was carried out on a sample of 128 Italian medium-sized businesses – hereafter MSBs - (76 family and 52 non-family businesses). We used the AIDA – Bureau van Dijk database to collect data referring to three years 2007, 2009 and 2014, respectively corresponding to the pre-crisis phase – 2007, the great recession – 2009, and the post-crisis phase – 2014. STATA software was used for analysing data and the analysis was organised into three steps. First, we collected the descriptive statistics. Then, we used a t-test to determine if businesses’ performance and solvency significantly differ in family and non-family businesses subgroups. In the last step, we performed a regression analysis to examine the relationship between firms’ profitability (dependent variable) and family ownership and solvency (independent variables). Contrary to previous research, we found that MSFBs performed worse at each stage of the crisis, especially during the harshest phase of the crisis. Results also show that family ownership negatively affected businesses’ profitability. On the contrary, solvency positively affected firms’ profitability at each stage of the crisis. Finally, we analysed and discussed a model case study, to better understand financial and economic dynamics of family firms during the analysed period. Although family firms’ performance during the recession period has been widely studied, they generally referred to large companies. Analyses haven’t considered MSBs, even if in recent years they have played an important role in several economic systems and show some distinctive features that can significantly differentiate them from large companies. The main contribution this study brings to the literature is investigating family business performance during a downturn, paying attention to MSBs.

Key words: Family business, medium-sized enterprises, performance, solvency, economic crisis.

Family firms play a significant role in several economic systems, in both industrialised and developing countries. According to one of the most acknowledged definitions, a family firm is a “business governed and/or managed with the intention to shape and pursue the vision of the business held by a dominant coalition controlled by members of the same family or a small number of families in a manner that is potentially sustainable across generations of the family or families” (Chrisman et al., 1999).

However, this definition cannot be used to determine the exact number of existing family businesses, or to carry out comparative studies between different countries. In fact, several analyses on the presence of family businesses in different countries, as well as numerous empirical studies on this topic, use different variables to operationalise the definition of family business and to measure the number of such companies (Astrachan et al., 2002; Klein et al., 2005).

Despite these difficulties, the available data clearly shows the presence, in Italy, of a very high percentage of family businesses. One of the most recent statistics shows that, in Italy, more than 75% of enterprises are family businesses, and this figure is not very different from that of leading countries in Europe (Germany 75%; France 75%, UK 65%; Spain 85%) (according to the estimations of the European Family Businesses Federation).

Consequently, in business research, knowing the performance of these enterprises and their motivations is of great concern, in order to understand how and if firms’ performance is affected by family’s involvement in firms’ ownership and governance (Gallo et al., 2004; Allouche et al., 2008; Amann and Jaussaud, 2012; Basco, 2013; Minichilli, et al., 2015).

Indeed, in studies on family businesses, the influence of family ownership and control on business performance is one of the most debated issues in recent years (Mazzi, 2012; Basco, 2013; Minichilli et al., 2015). Several scholars conducted research on this subject, adopting diverse theoretical perspectives. The agency theory, the stewardship theory, the resource based view and the socioemotional wealth were primary positions taken. Nevertheless, these studies do not offer unambiguous results (Enriques and Volpin, 2007; O’Boyle et al., 2012).

Some authors, following the agency theory framework, claim that family firms are more efficient than non-family firms (Fama and Jensen, 1983). When family members are involved in business ownership and management, risks of opportunistic behaviours (by managers) are reduced. So agency problems are absent thanks to the alignment of interests and objectives (Villalonga and Amit, 2006).

In contrast with this traditional point of view, other scholars have found that owner-manager and owner-owner complications (Villalonga and Amit, 2006) exist, because of possible negative relationships between family ownership and company performance. The main obstacles that can occur in family businesses include pursuing private benefits (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2001), entrenchment (Shleifer and Vishny, 1997), adverse selection (Lubatkin et al., 2005), nepotism and taking advantage of unearned benefits (Schulze et al., 2001).

In the last years some scholars have examined the connection between the family nature of a firm and its performance during a period of economic downturn. Their analyses proved that family businesses enjoy better performance than non-family businesses in various countries (Allouche et al., 2008; Amann and Jaussaud, 2012; Wu et al., 2012; Crespí and Martín-Oliver, 2015), given that they have a sounder financial situation (Amann and Jaussaud, 2012; Crespí and Martín-Oliver, 2015). In Italy other scholars have found similar results (Minichilli et al., 2015; Macciocchi and Tiscini, 2016).

Most research focused on large firms; studies on Italian Medium-Sized Businesses (hereafter MSBs) during the latest economic recession are nonexistent. Nonetheless, in Italy MSBs typify an important class of firms and have been playing an increasingly role in the economic system. This is why the aim of this paper is contribute to the development of this research field by concentrating on Italian MSBs. In particular, our aim is to compare Italian medium-sized family and non-family businesses, investigating whether or not family firms have presented higher solvency and profitability ratios during the recent economic downturn. In this paper, the results of our empirical research are presented.

Family ownership and control and firms’ performance

The agency theory framework has been widely used to investigate the relation between corporate governance and firms’ performance and additionally to contrast family and non-family businesses (Erbetta et al., 2013). Such studies have not produced unequivocal results (Enriquez and Volpin, 2007).

It has been claimed by some researchers that family firms typify a more efficient governance structure than non-family firms (Morck, 1988), owing to the fact that the concentration of ownership is in the hands of a small number of shareholders and the co-occurrence between ownership and control (Jensen and Meckling, 1976; Shleifer and Vishny, 1997).

The deep involvement of family members in ownership, management and control reduces the threat of opportunistic conduct and decreases possible problems emerging from the deviation of interests between principal and agent (Jensen and Meckling, 1976). As a result, conflicts are less frequent and business owners don't need to monitor managers and directors to promote alignment between managers, family and business objectives as often (Chrisman et al., 2004; Fama and Jensen 1983; Jensen and Meckling, 1976).

Furthermore, the number of shareholders in family firms is typically low, which favours the formation of a single, shared view of the company. For the same reason decisions are usually quicker and the chance of managers compromising shareholders’ interests and jeopardising firm performance is lower (Shleifer and Vishny, 1997).

In conclusion, according to the agency theory, family firms can achieve better results than non-family firms. According to Carney (2005), this result also stems from the fact that the coincidence between ownership and control produces three dominant behaviours: thrift, personality and particularism, causing family businesses to differ from other companies and allow reductions in agency costs, with positive consequences on business performance.

Other scholars have adopted the stewardship theory and affirm that family firms are characterized by long-run objectives and perspective, in view of the fact that their main concern is to establish the longevity of their firms (Breton-Miller and Miller, 2009).

Therefore, family businesses endure less managerial myopia (Stein, 1988, 1989), given that investment policies are more efficient (James and Harvey, 1999) and are effect to lesser degree by short-term economic conditions (Allouche et al., 2008). According to this view, the attitude of the stewards is a source of competitive advantage that positively affects the performance of family businesses (Eddleston and Kellermanns, 2007; Miller et al., 2008).

The concept “altruism” has been used by some scholars to characterise the posture of family firms, motivated by the shared well-being, mutual support and uniqueness of vision among family members. As a result, altruism contributes to lowering the likelyhood of opportunistic behaviour and helps to reduce agency costs (Parsons, 1986; Eisenhardt, 1989a; Schulze et al., 2001; Corbetta and Salvato, 2004).

Conversely, different researchers have claimed that altruism can be quite asymmetric in family firms and can jeopardise firms’ performance and shareholder value (Schulze et al., 2001). Family members may show preference for their private interests, risking the longevity of the business (free riding, opportunistic behaviours, shirking).

Furthermore, family ownership may also exclude family firms from external control mechanism. In family companies, top managers often have low professional expertise, as they are very often selected among family members. On the contrary public companies use the market to select managers with qualified skills and consistent with the needs of the company (Lauterbach and Vaninsky, 1999; Lane et al., 2006).

These last reflections are in stark contrast to what is claimed by agency theory perspective. In line with this reasoning, family businesses could show high agency costs and this cause us to question family firms as a more efficient governance model.

The “resource-based view” (hereafter RBV) is another perspective of analysis, which believes that resources are the foundation of a firm’s performance. If resources are unparalleled, adaptable to environment and rooted steadfastly in the business, they become a prospective source of competitive advantage (Penrose, 1959; Wernerfelt, 1984).

According to Habbershon and Williams (1999), “familiness” is the heart of resources and proficiencies assembled by family businesses. Familiness stems from the intercommunication of family business’s subsystems: family, family members and business. Determined factors–coined as “family factors”–are the outcome of this interaction. They make resources and capabilities unique and affect the performance of a family firm.

From this point of view, family firms can be regarded as a dynamic system, able to give rise to unique competences (distinctive familiness) or impede them from occurring (constrictive familiness), therefore affecting wealth creation. As a consequence, family businesses can be sharp stewards of their resources, because of their longtime perspective (Arregle et al., 2007).

At the same time, however, family’s will to control the company can limit financing options. Moreover, nepotism and entrenchment can prevent family firms from hiring qualified and competent managers (Bloom and Van Reenen, 2007; Mehrotra et al., 2011).

A new theoretical framework - “socioemotional wealth” (SEW) (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2007; Berrone et al., 2012) - was recently formulated to research on family firms and it is also adopted in the analysis of the family’s influence on a firm’s performance (Sciascia et al., 2014). According to this theoretical framework, decisions in family firms are heavily conditioned by their desire to protect SEW and maintain non-economic benefits - “affective endowments”. Family-centred, non-economic objectives generate a stock of socioemotional wealth that results in a unique outcome for family businesses.

Recently, Sciascia et al. (2014) focused on the role of family management and its influence on family firms’ profitability. Adhering to the SEW perspective, they carried out an empirical research study on a sample of Italian family businesses. Their results prove that family management can contribute to the improvement of a family firm's performance in later generational stages. In fact, authors argue that, in earlier generational stages, family firms are more focused on their socioemotional wealth, while in later phases they are more concerned with financial performance.

Similar results have been obtained from Arrondo-Garcia et al. (2016). They adopted the SEW perspective and analysed the performance of a sample of large Spanish family companies during the recent economic crisis. Their results show that first generation family businesses had worse financial performance (return on equity) compared to older family businesses during the same period (2006-2011). Debicki et al. (2017) offered some explanations about how pursuing non-economic objectives affects family business financial performance. However, further research are needed on this topic in order to better explain if and how family firms can reach better performance (Daspit et al., 2017)

In conclusion, clear-cut results are still missing and additional analysis on this subject matter is needed. As already highlighted by Mazzi (2012), none of the discussed theories have been able to exhaustively explain what is, if it exists, the link between family firms’ performance and family involvement in the business.

Different theoretical perspectives could be adopted to analyse the relationship between business performance and governance model, because each theory generates different hypotheses. That being the case, it’s difficult to put forward an explicit hypothesis on this topic. This uncertainty also remains when findings from empirical analyses are considered, as they are often characterised by ambiguous outcomes (O’Boyle et al., 2012).

This is why we have formulated some research questions about the relationship between family ownership and control and firms performance.

Family firms performance and economic downturns

Several researchers in the last years have doubted the ability of family businesses to come up against periods of crisis and have compared performances of family and non-family businesses.

Some authors (Allouche et al., 2008) investigated Japanese family and non-family firms in two separate years – 1998 and 2003 – respectively indicated by the Asian economic crisis and a period of economic recovery. These scholars demonstrated that family firms are able to outperform non-family firms.

Amann and Jaussaud (2012) produced evidence that family businesses are more impervious to crises, are more fast to recover, enjoy better performance and have a more vigorous financial structure, with better solvency ratios and lower leverage ratios. Other authors studied performance of the world’s largest companies from 2005 to 2008 and discovered that in periods of recession family companies performed better than non-family companies (Wu et al., 2012).

According to them, family businesses are able to make faster decisions and are more decisive in cutting costs, thanks to shared objectives among owners, managers, employees and executives. Scholars have also insisted that non-family firms perform better than family firms during economic upturn, given that family firms’ emphasis on control can reduce risk propensity and diminish the creativity and motivation needed to innovate.

Furthermore, it is clear that companies need qualified management skills in periods of recession, to be better able to tackle the crisis with effective actions. In periods of economic crisis it’s not enough for firms to be able to ensure their short-term survival. In fact they should also be able to prepare strategic initiatives that can ensure their long-term competitiveness (Sternad, 2012; Cesaroni and Sentuti, 2016). Family businesses, unfortunately, may not have sufficient managerial skills to execute such initiatives, given that they mainly select managers among family members, rather than turn to the market (Lane et al., 2006).

Other scholars have insisted that periods of recession can highlight owner-owner agency problems – Agency problem II (Villalonga and Amit, 2006). In fact, a crisis may prompt an owner family to take advantage of their position to achieve private benefits rather than up the company's profitability and competitiveness (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2001).

Contrastingly, other scholars have noticed that during economic downturns owner family predominantly make long-term oriented decisions for the survival of the business. Additionally, in order to strengthen the company’s financial structures, an owner family would invest increase the share of capital invested in the company and give up dividends (Macciocchi and Tiscini, 2016).

In accordance with this point of view, economic downturns could underline a distinguishing trait of family businesses, often set apart by their low predisposition to debt. As long long-term survival is their primary concern, owner families would be very prudent when making financing choices, so they don't increase their leverage ratio and avoid putting the company's control at risk because of a great dependence on lenders (Allouche et al., 2008; Amman and Jaussaud, 2012).

So far, analyses on relationship between family nature of a firm and its performance have mainly considered large firms. Analyses on MSBs still haven’t been performed, even though they play an increasingly important role in many countries, such as in Italy. In Italy MSBs are able to contribute to economic growth employment and innovation (UnionCamere, 2014). As a further matter, they also have some unique traits that can significantly distinguish them from large and listed firms (Palazzi, 2012). This is why we wonder whether findings emerged from previous research on performance and economic crisis–that mainly referred to large family firms–can be generalized to medium-sized ones.

According to O’Boyle et al. (2012) the relationship between the family nature of a firm and its performance is more favourable and potent in larger firms than in smaller firms. They did a meta-analysis to demonstrate this hypothesis but their results did not provide positive feedback.

Therefore, they called for further research to explore the impact of size in the relationship between family nature of a firm and its performance. As a consequence, it is significant to carry out further research and involve companies of all size classes, because so far analyses have only really taken large companies into consideration. For this reason our goal is to extend the scope of the analysis, considering medium-sized family firms. In particular, we want to understand if during the recent economic downturn:

RQ1: family firms perform better than non-family firms;

RQ2: family firms show a higher equity ratio than non-family firms.

Data collection

In order to answer the study research questions, an empirical research was carried out with the aim to compare the profitability and solvency of Medium-Sized Family Businesses (hereafter MSFBs) and non-family owned businesses during the recent recession. Following the definition given by the European Union Commission Recommendation in 2003, we classify a firm as medium when it has more than 50 employees but less than 250 and generates annual sales between 10 and 50 million euros.

Family businesses were identified considering companies in which a family holds a share of capital that allows it to control the company. We only considered private (non-listed) companies and classified a firm as a family business when an individual or a family (two or more family members) holds more than 50% of equity (Naldi et al., 2013, Minichilli et al., 2010). Since there isn’t an official database of Italian family businesses, we adopted a manual procedure to classify companies as family or non-family businesses, conducting an in-depth review of the ownership structure of the selected firms.

The empirical research study was conducted in Italy. This country is particularly interesting when analysing enterprises’ experiences during the recession because of the greater impact and duration of the crisis in Italy. Precisely, the research focused on MSBs located in Central Italy. This macro area–including Marche, Lazio, Tuscany and Umbria regions–is an important socio-economic zone with specific features consistent with our research questions: the industry structure and the latest economic trends.

From the point of view of industrial structure, this field exhibits the typical characteristics of an Italian industry, such as industrial dualism and a distinct productive specialisation in traditional sectors. Additionally, there is a very high number of MSBs, made up of 13% of the national total (Mediobanca and UnionCamere, 2015) and 83% of businesses are family owned (UnionCamere, 2014). According to the latest economic trends, the recession that began in 2008 has uniformly not had an effect on Italian regions.

According to the Bank of Italy Reports (Bank of Italy, 2009), the economy of Central Italy was severely affected in all sectors. Evidence of this is the substantial losses in terms of industrial value added from 2007 to 2013, amounting to -20.4%. This percentage is higher than that of Northern Italy where the North-West reported a 15.8% decrease and the North-East, -16.6%. However, in Southern Italy was the loss much more substantial, -29.9% (Bank of Italy, 2014).

In the first step of this research, we selected firms located in the Marche and Umbria regions, a geographical area with an extremely high presence of family businesses (UnionCamere, 2014) as well as a notable number of MSBs (Mediobanca and UnionCamere, 2015). In the next step of our research, the analysis will be broadened to include all medium-sized family and non-family businesses situated in Central Italy.

Data on firm profitability and solvency were collected for three years, characterised by profoundly different economic conditions: 2007, the pre-crisis phase; 2009, the great recession; and 2014, the post-crisis phase. We collected data from the AIDA – Bureau van Dijk database, which includes a wide range of financial and non-financial information on approximately 1 million Italian companies.

Applying the size and geographical area criteria, an ultimate sample of 128 MSBs was selected, representing 33% of the total number of MSBs in Central Italy (based on AIDA database). In 2007, there were 76 family businesses (about 60%) and 52 non-family businesses (40%). In addition, some firms changed their ownership structure from non-family to family ownership during the period of observation. As a result, in 2014, family businesses made up 67% of the database. This data is in alignment with prior studies, which confirm the prevalence of family businesses in the Italian economic system (Macciocchi and Tiscini, 2016; Faccio and Lang, 2002).

Data analysis

The following performance indicators and financial ratios were chosen to evaluate firms’ profitability and solvency:

(1) The Ebitda profit margin. It’s equal to earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation (Ebitda) divided by overall turnover and was adopted in order to measure firms profitability.

(2) The equity ratio. This ratio expresses the amount of assets financed by owners' investments, by comparing the total equity in the company to the total assets.

STATA software was used for data analysis, divided into three phases:

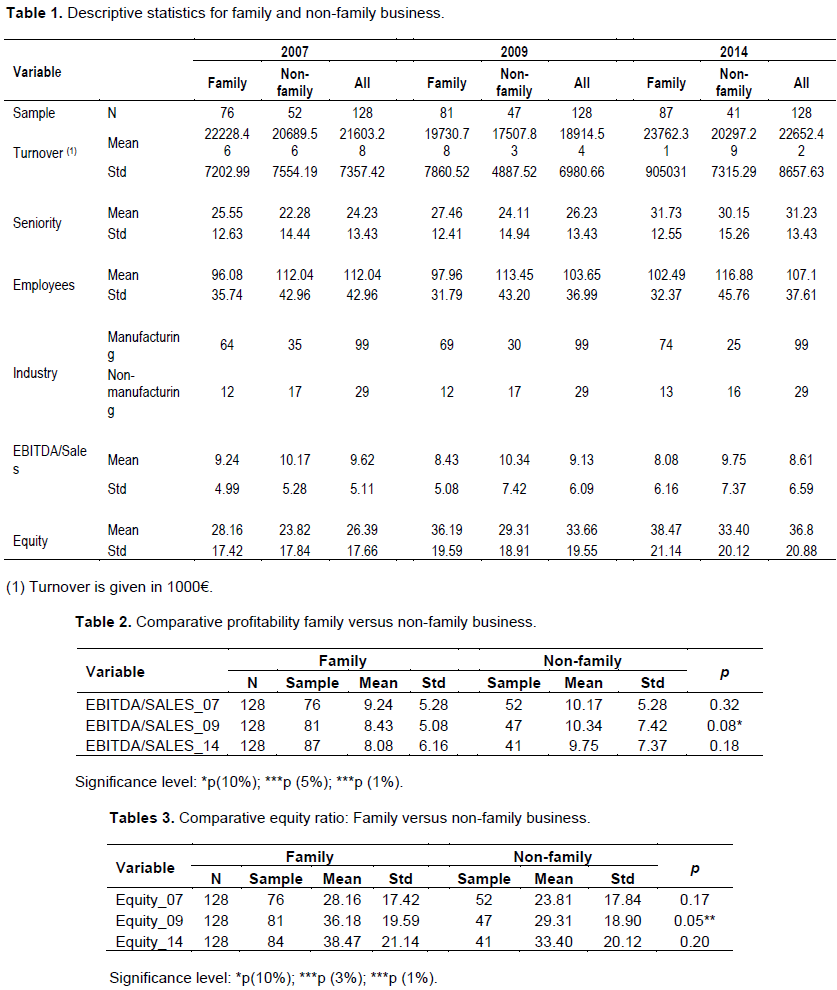

(1) We described the basic features of our sample providing the descriptive statistics for the main variables we used in our analysis: turnover, firm’s seniority, employees, industry, Ebitda margin and equity ratio (Table 1).

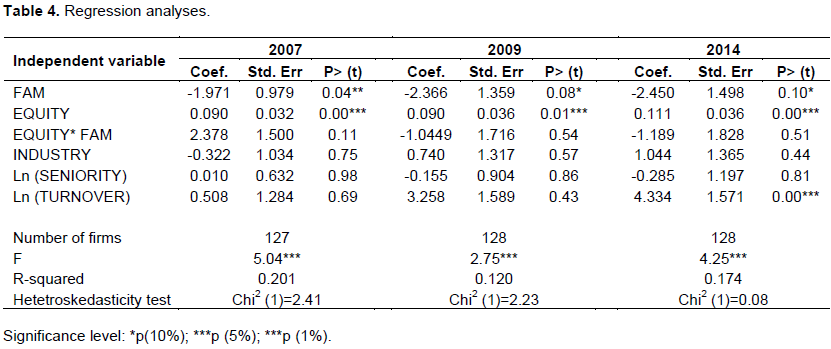

(2) We employed an independent t-test (Hamilton, 2013) to distinguish similarities and notable differences in profitability and solvency between family and non-family firms in the three years included in our analysis: 2007, 2009, 2014 (Tables 2 and 3).

(3) We employed a regression model for each year of analysis to assess if and how firms’ performance is affected by ownership structure and solvency, (Table 4). The Ebitda margin was used as the dependent variable. As independent variables we applied:

Case study

According to Eisenhardt (1989b), the combination of quantitative data with qualitative evidence can be highly synergistic. Qualitative method can bolster quantitative findings and better underline relationships revealed in the quantitative analysis.

In this perspective, data analysis was followed by a case study, involving a MSFB that greatly improved its solvency and managed to keep its economic performance despite the economic recession. For these reasons, the selected company represents an exemplary case study. It’s useful to better understand financial and economic dynamics of a prosperous family firm during the analysed period. The case analysed was selected within the sub-sample of family business.

Data collected from AIDA BvD database was combined with key data gathered by two in-depth, semi-structured, face-to-face interviews. Guided by a checklist, interviews were carried out in the company and involved the founder and his daughter (the future successor to the firm). Questions were aimed to collect information regarding the founder, company’s ownership, the successor, the impact of the crisis and the actions taken to deal with it. Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Data and information were analysed and results are presented and shortly discussed in the section devoted to the case study..

(1) A dummy variable (FAM), which equals one when the firm is a family-owned business and zero in any other way.

(2) The equity ratio (EQUITY).

(3) An interaction variable acquired by multiplying the variables FAM and EQUITY, in order to determine the combined effect of the previously mentioned variables on firm’s profitability. The variable EQUITY was converted into a dummy, taking 0.30 (approximately correlating with the distribution median) as the threshold value. Therefore, we coded 1, if a firm shows a value equal to or above 0.30, and 0 in any other way.

In accordance with prior studies on family firms’ performance (Claessens et al., 2002; Colombo et al., 2014), we examined some control variables: company size, industry, company seniority. Company size (TURNOVER) is measured by overall turnover per year. Company seniority (SENIORITY) is calculated by the number of years the firm has been in business. Both variables are altered by the natural logarithm. Lastly, we checked the industry (INDUSTRY) by using dummy variables based on the Italian industrial sectors (ATECO, 2007): code 1 for manufacturing firms; 0, otherwise.

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics from two sub-samples with regard to the period of three years considered. During the crisis period, all the selected companies decreased their sales (from about 21.6 mln € in 2007 to about 18.9 mln € in 2009). Turnover began to increase during the post-crisis phase and in 2014 it attained a level higher than in the pre-crisis period (about 22.6 mln €). Family firms’ turnover was higher than non-family firms’ turnover throughout the three years period.

In line with previous research (Corbetta et al., 2015), family-owned businesses have a longer life than non-family businesses. Family firms are also smaller than non-family firms. Manufacturing firms are more numerous both in the entire sample and in the sub-samples. This data situation is congruous with the economic structure of the geographical area analysed, distinguished by an high proportion of manufacturing companies (Istat, 2015).

Ebitda margin reveals that the entire sample endured a slow but steady decline during the analysed period. However, the profitability of non-family firms is without fail higher than that of family firms: 10.17 versus 9.24 in 2007, 10.34 versus 8.43 in 2009 and 9.75 versus 8.08 in 2014. Moreover, we found that while the profitability of family businesses declined in 2009, non-family firms reported a somewhat of an increase as compared to 2007. These findings are preliminary proof that, regardless of the economic situation, medium-sized non-family firms performed always better than MSFBs, particularly in 2009, characterized by a particularly harsh crisis.

Overall, sample companies improved their solvency level during the analysed period, passing from 26.39% in

2007 to 33.66% in 2009 and reaching 36.80% in 2014. In this span of time family firms experienced greater improvements in their solvency level and displayed a higher equity ratio than non-family firms did: 28.16% vs 23.82% in 2007, 36.17% vs 29.30% in 2009 and 38.47% vs 33.40 in 2014. To assess whether family and non-family firms’ profitability and equity ratio are statistically different from each other we used the t-test (Tables 2 and 3).

Evidence displays that non-family businesses performed considerable better than family firms at 10% (p = 0.08) in the year of recession (2009). The same result is corroborated for 2007 and 2014, however, throughout these years the differences between family and non-family firms aren’t at exceptional levels (respectively p = 0.32 and p = 0.18).

On the contrary, regarding financial structure, results show that in 2009 family businesses encountered a level of equity ratio significantly higher than that of non-family firms at 5% (p = 0.05) during the economic recession. This tendency is confirmed both for 2007 and 2014, but the differences between the two sub-samples aren’t important (respectively p = 0.17 and p = 0.20). Lastly, the regression model permitted us to assess if and how family ownership and equity ratio had an effect on firms’ profitability (Table 4).

Results reveal that family ownership (FAM) is always negatively and statistically related to company profitability in any type of economic condition (p = 0.04 in 2007; p = 0.08 in 2009; p = 0.10 in 2014). Simultaneously, the level of equity ratio (EQUITY) is always positively and statistically important at 1% when related to company profitability in diverse economic conditions, for all three years.

Moreover, we evaluated the combination effect of family ownership and equity ratio (EQUITY*FAM) on profitability. Results reveal that the interaction variable is positively associated to the profitability of the business during the pre-crisis period (2007) and negatively associated during the period of crisis (2009) and the recovery period (2014). Even if the correlation between ownership and solvency never becomes significant over the time, the tendency is clear. This means that family businesses’ solvency, during economic downturn and upturn, cannot counterbalance the negative influence of family ownership on firms’ profitability

In the last phase, we examined the control variable, and the industry variable (INDUSTRY) reveals a positive outcome for profitability over the time, except in 2007, which is negative. However, this impact is not significant during the three years. The firm seniority variable (SENIORITY) displays a negative impact on profitability during the crisis (2009) and post-crisis period (2014), not counting the pre-crisis time (2007). Nevertheless, the impact is always statistically beside the point. The turnover variable (TURNOVER) reveals a positive influence on margin Ebitda during the analysed period. However, one should observe that there is a positive and significance influence on recovery time (2014).

With this analysis, we answered the study RQs. The first RQ from this study inquired about Italian MSFBs and if they performed better than non-family firms during the recent economic recession. We discovered that family and non-family businesses underwent different levels of performance. However, without warning, family businesses achieved worse economic performance than non-family firms in every type of economic situation, especially in periods of recession. This result conflicts with those from previous research (Allouche et al., 2008; Amann and Jaussaud, 2012; Macciocchi and Tiscini, 2016; Wu et al., 2012), which revealed that family firms achieved better profitability level than non-family firms, above all during economic recession. However, these studies focused their attention on large companies, while our analysis only examines MSBs.

The second RQ questioned the level of equity ratio of Italian MSFBs, and if it was higher than non-family firms during the recent crisis. Our findings display that the equity ratio augmented for both the sub-samples from the pre-crisis to the upturn period. Nevertheless, family businesses presented a higher ratio as compared to non-family firms for each year. This result is congruous with Macciocchi and Tiscini (2016), who demonstrated that family firms encountered much more financial support from their shareholders during the economic downturn. So, a higher equity ratio may reveal family businesses owners’ stance on maintaining control of the business during the economic crisis and to affirm the required financial resources in economic upturn.

These findings are somewhat unexpected. In fact, the study analysis reveals that family firms had higher equity ratio than non-family firms but lower profitability. However, if a firm has a sounder financial structure as it is less leveraged, it should be more capable to deal with period of crisis and to achieve higher profitability level. In order to better comprehend how family ownership and equity ratio have had an impact on performance, a regression model was carried out the interaction variable was incorporated.

Results demonstrate that family ownership had a negative effect on economic performance, while solvency positively influenced profitability. The first proof is in contrast with the traditional view corroborated by the agency theory and proposes that MSFBs present a more efficient governance structure that of non-family ones. On the contrary, solvency appears to take on a pivotal role in each economic condition in order to maintain business profitability. In conclusion, regardless of the economic conditions, both family and non-family businesses should be less leveraged and should augment their equity ratio. Analysing the combination effect of family ownership and solvency level on profitability, however, we discovered that the favourable influence of a high solvency level is not sufficient to ensure higher profitability during the economic downturn and upturn, because the negative effect of family ownership always proves superior.

Unfortunately, we couldn’t obtain data on firms’ governance and managerialization, and so we cannot give an explanation for the reason for such results. However, we can hypothesise that some problems may become apparent from these aspects. In fact, even if MSFBs are more often than not characterised by a significant level of professionalisation (Palazzi, 2012), managers involved are often appointed among family members and frequently have less skills than those in public companies (Lauterbach and Vanisky, 1999; Lane et al. 2006). Prior research underlined that non-family professional managers may have a pertinent role in family firms (Songini and Vola, 2015), and according to Lane et al. (2006), companies should turn to the market for talented people. This is primarily true in a period of economic crisis, when high-level managerial skills are crucial for the selection and implementation of effective strategies, which can be used to confront the crisis without undermining the business’ competitiveness (Sternard, 2012). Thus, a lack of suitable managerial skills could undermine the competitiveness of the business and reduce its economic performance. In this perspective, results are consistent with the perspective of “familiness”, considered by the RBV as a factor that may prevent the development of the business and affect their performance (Bloom and Van Reenen, 2007; Mehrotra et al., 2011).

At the same time, a second explanation could be related to the cost structure of the business. D’Aurizio and Romano (2013) analysed how Italian family businesses reacted to the economic crisis in terms of workforce level adjustment. These authors provided empirical evidence that Italian family and non-family firms adopted divergent paths in their employment policies. In particular, during the recent recession, family firms safeguarded workplaces more than non-family businesses did. According to the authors, this choice is due to the crucial role of the non-pecuniary benefits of the family business owners and is based on the psychological relation that ties them to their community of reference. Thus, the poor economic performance of family businesses could be due to fixed labour costs, which remained stable even if the economic performance declined. This approach could further worsen the family firms’ efficiency and performance. In this perspective, SEW arguments–the non-economic and socioemotional goals prevail over the financial and economic goals (Berrone et al., 2012) are particularly consistent with our results.

An exemplary case study

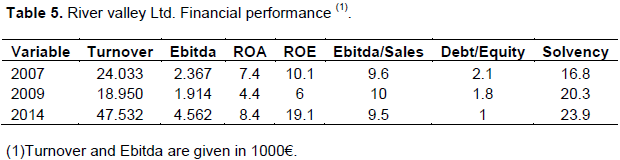

After the statistical analysis of the data, in this session we briefly present and discuss a case study, involving a family firm included in our sample. The selected company – River Valley – can be considered an exemplary case, as during the period under observation – 2007-2014 – greatly improved its solvency and managed to keep its economic performance, despite the economic recession.

River Valley Ltd. was founded in 1999 by Matt Whales . Matt and his family hold the majority share of the company, while a Polish partner holds the minority share. The company designs and manufactures heat exchangers. The company has experienced rapid growth in the last years. Today it’s one of the most important producers worldwide of aluminum and copper heat exchangers for domestic gas boilers. It’s also entering the market of aluminum parallel flow condensers for the refrigeration and climatization industry. River Valley strategic guidelines are innovation and quality. In fact it has always invested in design and manufacturing innovation, technical competitiveness, product quality, full cooperation with their clients to develop new projects.

The company has not given up this policy in spite of the economic and financial crisis that started in the late 2008. In fact, River Valley continued to invest heavily in research and development, new equipment, machinery and human resources. The new investments enabled it to improve efficiency in production processes and to gain new markets, especially abroad, thanks to its high quality products. Consequently, although in 2009 the company’s economic performance worsened (Table 5), in 2014 its financial statements shows strong signs of improvement.

This investment policy was made possible thanks to the decision to continually reinvest profits to self-finance the company. In fact more than 12% of investments were self-financed. This attitude proved successful and enabled the company to improve its profitability and to strengthen its financial position. In the period 2007 to 20114, in fact, the debt / equity ratio more than halved and the solvency ratio greatly increased.

From this point of view, the experience of this company clearly confirms previous analyses (Macciocchi and Tiscini, 2016) showing family firms’ low predisposition to indebtedness and the availability of the owner family to give up dividends in order to strengthen the company’s financial structures. Behind this attitude of prudence in financing decisions is the desire of the owner family not to put at risk the long-term survival of the company and to maintain the company’s control in the long run.

At the same time, this case demonstrates the importance of innovation to maintain the company's long-term competitiveness. Thanks to a solid financial structure, the company has been able to pursue a constant policy of technological innovation and investment in R&D. The latter played a key role in enabling the company to improve the company's competitiveness and overcome the crisis with improved economic performance.

Starting with the analysis of different theories addressing the binomial family business and performance, this article compares family and non-family firms during the recent recession. Contrary to previous research, which mainly focused on large firms and listed companies (Allouche et al., 2008; Amann and Jaussaud, 2012; Wu et al., 2012; Macciocchi and Tiscini, 2016), we only considered private MSBs. The study findings show that MSFBs underperformed compared to non-family firms during the period of recession. Moreover we highlight that solvency level played a crucial role in positively influencing business profitability.

The study extends previous research about family businesses’ performance during the recent economic crisis (Amann and Jaussaud, 2012; Minichilli et al., 2015 Macciocchi and Tiscini, 2016) by exploring the influence of family control in private MSBs. In contrast to other research, always carried out in Italy, but referring to large companies (Macciocchi and Tiscini, 2016), we have found that the family nature of a firm can have a negative influence on its profitability.

Moreover, according to the study findings, a higher level of solvency cannot offset this negative effect. Based on previous research (Lauterbach and Vanisky, 1999; Lane et al., 2006; Romano and D’Aurizio, 2013), we suppose that the reason for this difference can be twofold. On one hand, according to the concept of “constrictive familiness” considered by RBV, the lowest performance of family businesses compared to non-family firms could be due to the nepotism phenomenon, which can undermine the managerialisation and professionalisation of the business. In fact, due to nepotism, managerial skills–especially crucial during economic crisis–are restricted to those possessed by family members. On the other hand, consistent with SEW assumptions, poor performance of family businesses could be due to their desire to safeguard workplaces–more than non-family businesses have done–in order to preserve their relationship with their community and possible even their imagine. In other words, even during economic crisis, MSFBs confirmed that non-economic purposes prevail over the financial and economic goals. So future research should be designed to further investigates the characteristics of MSFBs - management level and governance system first of all. The aim should be to understand how these features can affect the performance of these businesses.

This study has several limitations that may extend opportunities for future research. First, we consider a specific and restricted geographical area, and this has influenced our results and limited their generalisation. A wider national study and a multi-country empirical research comparing family and non-family firms’ performance during economic crisis across different nations are suggested. Second, the relationship between family ownership and profitability has been analysed overlooking other variables related to ownership (presence of family or non-family shareholders), governance model (board composition and managerialisation level) and generation in control (first, second, etc.). Indeed these variables could affect company performance. We also didn’t take into consideration that different types of family businesses exist based on a diverse level of family control and/or diverse involvement of family members in business ownership and governance. Future research should consider these variables, maintaining the focus on MSBs. Third, we only used the Ebitda profit margin as a performance indicator. Other performance indicators (in primis, Return on Assets-ROA and Return on Equity-ROE) should be applied in future research.

This study also has some implications for practice. First, evidence shows that in every type of economic condition, solvency level plays a crucial role in order to preserve a business’ profitability. In other words, regardless of the economic situation, both family and non-family businesses should increase their solvency level in order to enhance the performance of the firm. Second, some considerations arise about the professionalisation and managerialisation of MSFBs. In line with Sciascia et al. (2014), we don’t affirm that family firms must necessarily be managed by non-family members. However, as the authors suggest, family firms may improve their performance thanks to “the introduction of adequate governance mechanisms (for example, a board of directors, including independent directors) and the use of an incentive system oriented to focus family managers’ attention on financial goals.” We think this is particularly true for MSFBs in which managers assume a key role in maintaining the competitiveness of the business, especially during recession. However, further analysis on the relation between family nature of MSBs and firm performance is needed, in order to offer family businesses behavioural guidelines that are suitable for their specific features.

The authors have not declared any conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

|

Allouche J, Amann B, Jaussaud J, Kurashina T (2008). The Impact of Family Control on the Performance and Financial Characteristics of Family versus Nonfamily Businesses in Japan: A Matched-Pair Investigation. Fam. Bus. Rev. 21(4):315-329.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Amann B, Jaussaud J (2012). Family and non-family business resilience in a economic downturn. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 18(2):203-223.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Arregle JL, Hitt MA, Sirmon DG, Very P (2007). The development of organizational social capital: Attributes of family firms. J. Manage. Stud. 44(1):73-95.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Arrondo-Garcia R, Fernandez-Mendez C, Menendez-Requejo S (2016). The growth and performance of family businesses during the global financial crisis: The role of the generation in control. J. Fam. Bus. Strat. 7(4):227-237.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Astrachan JH, Klein SB, Smirnyos KX (2002). The F-PEC scale of family influence: A proposal for solving the family business definition problem. Fam. Bus. Rev. 15(1):45-58.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bank of Italy (2009), Annual Report on 2008, May 29, Rome.

View

|

|

|

|

|

Bank of Italy (2014), Annual Report on 2013, May 30, Rome.

View

|

|

|

|

|

Basco R (2013). The family's effect on family firm performance: A model testing the demographic and essence approaches. J. Fam. Bus. Strat. 4(1):42-66.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Berrone P, Cruz C, Gómez-Mejía LR (2012). Socioemotional wealth in family firms: Theoretical dimensions, assessment approaches, and agenda for future research. Fam. Bus. Rev. 25(3):258-279.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bloom N, Van Reenen J (2007). Measuring and explaining management practices across firms and countries. Q. J. Econ. 122(4):1351-1408.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Breton-Miller I, Miller D (2009). Agency vs. Stewardship in Public Family Firms: A Social Embeddedness Reconciliation. Entrep. Theory Pract. 33(6):1169-1191.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bretonâ€Miller L, Miller D (2009). Agency vs. stewardship in public family firms: A social embeddedness reconciliation. Entrep. Theory Pract. 33(6): 1169-1191.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Carney M (2005). Corporate governance and competitive advantage in family-controlled firms. Entrep. Theory Pract. 29(3):249-265.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Cesaroni FM, Sentuti A (2016). Strategie ambidestre e crisi economica: le peculiarità della piccola impresa. PI/Small Bus. 1:54-77.

|

|

|

|

|

Chrisman JJ, Chua JH, Litz RA (2004). Comparing the agency costs of family and non-family firms: Conceptual issues and exploratory evidence. Entrep. Theory Pract. 28(4):335-354.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Chrisman JJ, Chua JH, Sharma P (1999). Defining the family business by behaviour. Entrep. Theory Pract. 23(4):19-39.

|

|

|

|

|

Claessens S, Djankov S, Fan LHP Lang (2002). Disentangling the incentive and entrenchment effects of large shareholdings. J. Financ. 57(6):2741-2771.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Colombo MG, De Massis A, Piva E, Rossi-Lamastra, Wright M (2014). Sales and Employment Changes in Entrepreneurial Ventures with Family Ownership: Empirical Evidence from Highâ€Tech Industries. J. Small Bus. Manage. 52(2):226-245.

|

|

|

|

|

Corbetta G, Minichilli A, Quarato F (2015). VII Rapporto: Osservatorio AUB – Aidaf, Unicredit, Bocconi sulle aziende familiari italiane.

View

|

|

|

|

|

Corbetta G, Salvato C (2004). Self-serving or self-actualizing? Models of man and agency costs in different types of family firms: A commentary on "Comparing the agency costs of family and non-family firms: Conceptual issues and exploratory evidence". Entrep. Theory Pract. 28(4):355-362.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Crespí R, Martín-Oliver A (2015). Do Family Firms have Better Access to External Finance during Crises? Corp. Gov. 3 (23):249-265.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

D'Aurizio L, Romano L (2013). Family Firms and the Great Recession: Out of sight, out of mind? Bank of Italy, Working Papers, n. 905.

View

|

|

|

|

|

Daspit JJ, Sharma P, Long RG (2017). A Strategic Management Perspective of the family Firm: Past Trends, New Insights, and Future Directions. J. Manage. Iss. 29(1):6-29.

|

|

|

|

|

Debicki B, Randolph RVDG, Sobczak M (2017). Socioemotional wealth and family firm performance: A stakeholder approach. J. Manage. Iss. 29(1):82-111.

|

|

|

|

|

Eddleston KA, Kellermanns FW (2007). Destructive and productive family relationships: A stewardship theory perspective. J. Bus. Venturing, 22(4):545-565.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Eisenhardt KM (1989a). Agency theory: an assessment and review. Acad. Manage. Rev. 14(1):57-74.

|

|

|

|

|

Eisenhardt KM (1989b). Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manage. Rev. 14(4): 532-550.

|

|

|

|

|

Enriques L, Volpin P (2007). Corporate governance reforms in Continental Europe. J. Econ. Perspect. 21(1):117-140.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Erbetta F, Menozzi A, Corbetta G, Fraquelli G (2013). Assessing family firm performance using frontier analysis techniques: Evidence from Italian manufacturing industries. J. Fam. Bus. Strat. 4(2):106-117.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Faccio M, Lang LPH (2002). The ultimate ownership of western European corporations. J. Financ. Econ. 65(3):365-395.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Fama EF, Jensen MC (1983). Separation of ownership and control. J. Law Econ. 26(2):327-349.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gallo MA, Tápies J, Cappuyns K (2004). Comparison of family and nonfamily business: financial logic and personal preferences. Fam. Bus. Rev. 17(4):303-318.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gómez-Mejía L, Nu-ez-Nickel M, Gutierrez I (2001). The role of family ties in agency contracts. Acad. Manage. J. 44(1):81-95.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gómez-Mejía LR, Haynes KT, Nú-ez-Nickel M, Jacobson KJ, Moyano-Fuentes J (2007). Socioemotional wealth and business risks in family-controlled firms: Evidence from Spanish olive oil mills. Admin. Sci. Quart. 52(1):106-137.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Habbershon TG, Williams ML (1999). A resource-based framework for assessing the strategic advantages of family firms. Fam. Bus. Rev. 12(1):1-25.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hamilton LC (2013). Statistics with Stata: Updated for Version 12. 8th ed. Boston: Brooks/Cole: pp. 145-150.

View

|

|

|

|

|

Istat (2015). Rapporto sulla competitività dei settori produttivi. Istituto nazionale di statistica.

View

|

|

|

|

|

James Jr, Harvey S, (1999). Owner as Manager, extended horizons and the family firms. Int. J. Econ. Bus. 6(1):41-55.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Jensen MC, Meckling WF (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. J. Financ. Econ. (3):305-360.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Klein SB, Astrachan JH, Smyrnios KX (2005). The F-PEC scale of family influence: Construction, validation and further implication for theory. Entrep. Theory Pract. 29(3):321-338.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lane S, Astrachan J, Keuyt A, McMillan K (2006). Guidelines for family business boards of directors. Fam. Bus. Rev. 19(2):147-167.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lauterbach B, Vaninsky A (1999). Ownership Structure and Firm Performance: Evidence from Israel. J. Manage. Gov. 3(2):189-201.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lubatkin M, Schulze W, Ling Y, Dino R (2005). The effects of parental altruism on the governance of family-managed firms. J. Organ. Behav. 26(3):313-330.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Macciocchi D, Tiscini R (2016). Behavior of family firms in financial crisis: cash extraction or financial support? Corp. Own. Control 13(2):296-307.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mazzi C (2012). Family business and financial performance. Current state of knowledge and future research challenges. J. Fam. Bus. Strat. 2(3):166-181.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mediobanca, Unioncamere (2015). Le medie imprese industriali italiane (2005-2014), Mediobanca Ufficio Studi.

View

|

|

|

|

|

Mehrotra V, Morck R, Shim J, Wiwattanakantang Y (2011). Must love kill the family firm? Some exploratory evidence. Entrep. Theory Pract. 35(6):1121-1148.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Miller D, Le Breton-Miller I, Scholnick B (2008). Stewardship vs. stagnation: An empirical comparison of small family and non-family businesses. J. Manage. Stud. 45(1):51-78.

|

|

|

|

|

Minichilli A, Brogi M, Calabrò A (2015). Weathering the storm: Family ownership, governance, and performance through the financial and economic crisis. Corp. Gov. 24(6):552-568.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Minichilli A, Corbetta G, MacMillan I (2010). Top management teams in family controlled companies: 'Familiness', 'faultliness', and their impact on financial performance. J. Manag. Stud. 47:205-222.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Morck R, Scheifer A, Vishny RW (1988). Management ownership and market valuation: An empirical analysis. J. Financ. Econ. 20(1):293-315.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Naldi L, Cennamo C, Corbetta G, Gómez-Mejía L (2013). Preserving Socioemotional Wealth in Family Firms: Asset or Liability? The Moderating Role of Business Context. Entrep. Theory Pract. 37(6):1341-1360.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

O'Boyle Jr EH, Pollack JM, Rutherford MW (2012). Exploring the relation between family involvement and firms' financial performance: A meta-analysis of main and moderator effects. J. Bus. Venturing 27(1):1-18.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Palazzi F (2012). Medie imprese italiane, sviluppo e corporate finance, FrancoAngeli.

|

|

|

|

|

Parsons D (1986). The employment relationship: Job attachment, work effort, and the nature of contracts. In O Ashenfelter, R Layard (eds), The Handbook of labor Economics: 789-848. Amsterdam: North Holland.

|

|

|

|

|

Penrose ET (1959). The theory of the growth of the firm. New York: John Wiley.

|

|

|

|

|

Schulze WS, Lubatkin MH, Dino RN, Bucholtz AK (2001). Agency relationships in family firms: Theory and evidence. Organ. Sci. 12(2):99-116.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sciascia S, Mazzola P, Kellermans FW (2014). Family management and profitability in private family-owned firms: Introducing generational stage and the socioemotional wealth perspective. J. Fam. Bus. Strat. 5(2):131-137.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Shleifer A, Vishny RW (1997). A survey of corporate governance. J. Financ. 52(2):737-783.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Songini L, Vola P (2015). The Role of Professionalization and Managerialization in Family Business Succession. Manage. Control 1:9-43.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Stein JC (1988). Takeover threats and managerial myopia. J. Polit. Econ. 96(1):61-80.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Stein JC (1989). Efficient capital markets, inefficient firms: A model of myopic corporate behavior. Q. J. Econ. pp.655-669.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sternad D (2012). Adaptive Strategies in Response to the Economic Crisis: A Cross-Cultural Study in Austria and Slovenia. Manag. Glob. Transitions: Int. Res. J. 10(3):257-282.

|

|

|

|

|

UnionCamere (2014), Rapporto Unioncamere 2014. Imprese, comunità e creazione di valore. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Villalonga B, Amit R (2006). How do family ownership, control and management affect firm value? J. Financ. Econ., 80(2):385-417.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Wernerfelt B (1984). A resource-based view of the firm. Strateg. Manage. J. 5(2):171-180.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Wu S, James M, Wang B, Jung J (2012). An Agency approach to family business success in different condition economics. Int. J. Manage. Pract. 5(1):25-36.

Crossref

|

|