ABSTRACT

Family business succession is considered inherent to family businesses and represents a critical process that is generally characterised by resistance to change. This study aims to investigate the role of management accounting systems (MASs) in family business succession, in order to understand how changes in MASs during the succession across different family generations can help the succession process itself, facilitating the rise of the new leader, supporting changes, and reducing resistance to them. The research adopts a case study approach, focusing on organizational routines and their changes, at the same time taking into account the socioemotional wealth of the family firm. Evidence from the study shows the strategic role of MAS in managing the succession process, through the implementation of new routines and rules in helping the decision-making process and in achieving the firm’s leadership.

Key words: Family business succession, management accounting changes, routines, socioemotional wealth.

Family businesses have played a significant role in supporting the development of western civilizations and economies (Astrachan and Shanker, 2003; Klein, 2000; Shanker and Astrachan, 1996), driving economic development in the early stages of industrialization in many countries (Bird et al., 2002; Hall, 1988).

Various research projects have been conducted over the last three decades to analyse the operations of family firms. Family business literature has largely investigated corporate governance and ownership; moreover, a good deal of qualitative and quantitative research in this field has focused on succession (Brockhaus, 2004; Chrisman et al., 2005), pointing out that several factors could play a relevant role in making the transfer to one generation to another successful (De Massis et al., 2008). Scholars have paid comparatively less attention to the process of goal formulation or corporate social responsibility issues; other streams of research, despite their relevance to the succession process, have also been fairly neglected.

More concretely, it is noteworthy that accounting is one of the most under-investigated streams of research in family business studies (Songini et al., 2013), notwithstanding being one of the oldest business disciplines. Only recently scholars have increased their efforts in this direction. The literature review of Salvato and Moores (2010) concerning accounting and family business reveals that 47 papers were published between 1989 and 2010: 35 of them concerned financial accounting, 9 were focused on auditing and only 3 papers investigated management accounting in the family business field.

Accordingly, Salvato and Moores (2010) call for more studies, proposing several paths of research at the accounting–family business interface. More specifically, they suggest investigating the role of management accounting systems (MASs) in supporting family business succession. Along the same line, Prencipe et al. (2014) argue that the impact of management control systems on ownership transition to a later generation is one of the areas that deserve attention.

As a matter of fact, only a few studies have focused on these issues, highlighting the role of MASs in supporting professionalization of a family firm and transmitting knowledge across generations (Amat et al., 1994; Giovannoni et al., 2011); moreover, the study of Hiebl et al. (2013) provides a conceptual model to investigate the benefits of MASs for family businesses. Even if these studies have significantly improved our knowledge of the field, they do not consider in detail the potential role of MASs, not only in supporting the succession but also in enhancing the role of the new leader of the family firm.

Accordingly, this study aims to contribute in this respect, investigating the role of MASs in family business succession by interpreting succession as a dynamic process (Cater III et al., 2016). More specifically, from a theoretical viewpoint, this study has roots in both family business and management accounting literature, investigating the idea that MASs and management accounting changes can facilitate the succession process from one generation to another.

Considering that the succession transition determines significant changes in family firms in terms of family relations as well as routines and rules (Kansikas and Kuhmonen, 2008), succession has been interpreted as a process of moving appropriate routines to the next generation and eliminating outdated ones.

From a methodological perspective, as explained in the third section where findings are presented and discussed, a case study approach has been carried out, coherently with Leppäaho et al. (2016), whose literature review suggests using this approach in a critical way to contribute to a scientific pluralism in the field. The concluding section will add further elements of discussion and highlight further developments of the research.

Family business succession as a process

In the last decades, studies of family businesses have focused on the topic of succession (Chrisman et al., 2005), which is considered inherent to family businesses: Ward (1987) defines a family business as ‘one that passes from one generation to another’. The related literature (Gilmore and McCann, 1983; Gordon and Rosen, 1981; Handler, 1990, 1992) considers succession as a multi-stage process that exists over time (De Massis et al., 2008).

Scholars have identified this multi-stage process through a life-cycle approach (Churchill and Hatten, 1987; Longenecker and Schoen, 2002). Handler (1990) typifies succession as ‘a mutual adjustment process between the founder and the next-generation family members’. The author delineates the progression as transferral of leadership experience, authority, decision-making power and equity, as well as knowledge and ideas (Cabrera-Suarez et al., 2001; Perricone et al., 2001).

However, some discontinuity may characterise this process of change because of the unexpected death or illness of the founder (or one of the family members). According to Cherchem (2017), family firms that wish to safeguard long-term entrepreneurial orientation are expected to introduce changes in their cultural patterns when more than one generation is involved.

Furthermore, succession can experience several potential difficulties that can result in businesses being sold or liquidated (Gersick et al., 1997), as shown by evidence in several studies (Aronoff et al., 2010). It is noteworthy that only 12% of family firms reach the third generation, while only 3% reach the fourth or further generations (Allio, 2004). This would constitute a loss not only for the family but also for the local community.

According to Hiebl et al. (2013), the main reasons for this high rate of failure are insufficient strategic planning of succession, and the difficulty observed in many family firms of disseminating tacit and implicit knowledge in the succession process (Handler, 1994) from one generation to another. Along these lines, Nordqvist et al. (2013) emphasise the importance of adopting formal mechanisms that support the succession process, and findings from Cherchem (2017) emphasise the relevance of enhancing formalization and control system in family firms to ensure a long-term entrepreneurial orientation.

Transitioning to a new family generation stage of ownership after succession is a change that can have profound effects on both the family and the firm. Resistance to change on the part of the founder of a family firm throughout the succession process can be investigated through different perspectives (Churchill and Lewis, 1983; Goldberg and Wooldridge, 1993; Greiner, 1972; Kets de Vries, 1985; Levinson, 1971; Schein, 1983, 1985; Shepherd and Zacharakis, 2000).

GoÌmez-MejiÌa et al. (2001, 2007) have proposed taking into consideration the relevance of non-economic aspects, since family firms are typically orientated to the preservation of their socio-emotional wealth (Berrone et al., 2012), because of the strong family values which permeate the organization: ‘factors like emotional attachment, sibling involvement, sense of legacy, family control, and concern for reputation, among many others, give family firms their distinctiveness’ (Gómez-Mejía et al., 2001).

Accordingly, understanding the role of family relations in managing succession sheds light on the emotional aspects of the firm’s ownership transition, suggesting taking into consideration the social and cultural contexts where the succession occurs (Gottardo and Moisello, 2017). Indeed, the transition from one generation to another is more than just a change of ownership of the firm, and the relationship between old and new owners influences entrepreneurial activities during the transition phase. The succession process involves inter-generational teams based on family ties, which requires systematic attention to socialization, formal ownership and knowledge (Sharma et al., 2003).

Brockhaus (2004) has also emphasised the importance of the relationship between the founder and the successor(s) in determining the process, timing and effectiveness of the succession itself (Handler, 1990, 1992; Hollander and Elman, 1988; Davis and Haverston, 1998). The succession transition imposes significant changes on family businesses in terms of their ownership structure, routines and rules, and family relations.

Along these lines, Kansikas and Kuhmonen (2008) suggested the adoption of an evolutionary economics approach in understanding the succession process. A fruitful combination derives from a simple observation: succession is a crucial step in the life cycle of a family firm and, within this context, it essentially consists in managing changes over time. From this perspective, family firms can be considered as carriers of specific sets of routines. Succession can be interpreted as a process in which appropriate routines should be transferred to the next generation and outdated routines should be eliminated, in accordance with not only economic goals but also the above-mentioned socio-emotional factors.

According to Becker (2004), routines provide some degree of stability as well as a contrast required to detect novelty, that is, to make it possible to map organizational change. Taking into account that routines are triggered by the actions of individuals and/or by external cues (Bisogno et al., 2015), the transition from one generation to another plays a crucial role in affecting routines. The selection of routines is a crucial process for family firms, consisting in finding a correct balance between homogeneity and diversity. Succession represents both a problematic and an opportune moment, during which the organizational culture is selected, by passing on to the successor the appropriate routines and by eliminating the outdated ones.

The role of management accounting systems in the family business succession

According to the Chartered Institute of Management Accountants, a management accounting system is ‘the process of identification, measurement, accumulation, analysis, preparation, interpretation and communication of information used by management to plan, evaluate and control within an entity and to assure appropriate use of and accountability for its resources‘ (see also Salvato and Moores, 2010).

Scholars have largely defined accounting practices as organizational routines (Nelson and Winter, 1982), while at the same time suggesting investigating management accounting in the context in which it occurs (Ahrens and Chapman, 2002, 2007; Burns and Scapens, 2000; Hopwood, 1983). Therefore, MASs should play a central role in the succession process from one generation to another, providing several business-specific benefits.

Taking into account that family business systems consist of three interrelated circles (ownership, business and family; Gersick et al., 1997), Hiebl et al. (2013) have used this model as a reference to demonstrate the following specific benefits deriving from the use of management accounting:

1. Ownership benefits, such as increasing the transparency for potential outside investors and creditors as well as enabling the introduction of additional non-family investors.

2. Business benefits, such as supporting fact-based decision making for both family and non-family managers and directors; and

3. Family benefits, such as improving the transparency also for non-active family members and facilitating business succession due to a codification of formerly tacit knowledge.

Accordingly, a proper usage of management accounting could add value to a family firm, helping to reach a balance between emotions and facts in supporting the decision-making process while at the same time reducing the risk of business failure (GoÌmez-MejiÌa et al., 2007).

As observed by Berrone et al. (2012), protecting SEW to maximize socio-emotional endowments does not necessarily imply that all decisions will lead to economic losses. Therefore, strategic decisions are supposed to be made with the aim of maximizing both components (SEW and financial outcomes). On the other hand, management accounting and management control practices can help codify tacit knowledge to support knowledge transfer better. More specifically, during the succession, the MAS can facilitate the above-mentioned transferral to the successor of the appropriate routines, eliminating the outdated ones in the process.

Scapens (1994) points out that MASs comprise ‘institutionalized routines which create some measure of stability in day-to-day organizational behaviour’. The institutionalization of accounting practices is used to legitimize organizational activities and mediate conflicts through accounting mechanisms, where organizational processes and decision-making activities are taken for granted by members, helping leaders to legitimate their decisions (Scapens, 1994).

The study of Moores and Mula (2000) has pointed out that family firms rely on both formal and informal controls, whose characteristics and salience vary according to the life cycle stage of the family firm. Building on this last concept, Giovannoni et al. (2011) have analysed accounting systems and their role during processes of change and transition within this kind of firm. Their findings are coherent with the ideas that MASs are able to ‘influence perceptions, change language and infuse dialogue, thereby permeating the way in which priorities, concerns and worries, and new possibilities for action are expressed’ (Hopwood, 1990). These factors increase the formalization of a family business, which is considered the ideal setting to explore the role of management accounting in defining organizational structures and decision-making processes in all life cycles. The study of Giovannoni et al. (2011) mainly refers to the role of an MAS in supporting the professionalization of a family firm (they investigated the case of Monnalisa) and in reproducing the founder’s knowledge of the business. However, one of the main issues in the succession process is the relationship between the founder and the successor(s) in determining the process, timing and effectiveness of the succession, at the same time strengthening the role of the successor(s).

According to Scapens (1994) and Nelson and Winter (1982), accounting rules and routines enable organizational and decision-making activities to be passed from one generation to another through evolutionary processes. Scholars have affirmed that MASs need to be read as a ‘language’ that helps to anticipate the future, to assess and plan actions, and to set values and ideas concerning businesses’ behaviour based on past results. Based on management accounting outcomes, the owner can justify his decisions and communicate expectations and views while providing organizational structure and relationships of autonomy and dependence. Assuming this theoretical framework as a reference, the present study deals with the role of the MAS, both in supporting the succession and in enhancing the role of the new leader of the family firm, in contrast with previous research in the field (Giovannoni et al., 2011) that focused more on professionalization of family members during the succession process.

More specifically, the research questions of the present study can be expressed in the following terms: Does the MAS facilitate the succession from one generation to another? How can MASs affect organizational routines of family firms during the succession? Does an MAS support the aspiration of the new leader (after the succession) to achieve legitimacy?

The literature review of Prencipe et al. (2014) highlights that the (few) identified management accounting studies of family firms are mostly based on survey data and case study analysis. Case-oriented qualitative research is suitable for research into both family businesses (De Massis and Kotlar, 2014; Leppäaho et al., 2016; Nordqvist and Zellweger, 2010) and management accounting (Ahrens and Chapman, 2006; Hesford et al., 2007) in order to investigate complex processes over the different life cycles of the focal organizational entity.

Ryan et al. (2003) and Scapens (1990) argue that case studies offer the researcher the possibility of understanding the nature of management accounting in practice, not only in terms of techniques and procedures, but also in terms of which of them are used and the way in which they are used. Moreover, the emerging nature of management accounting research in the family business field suggests adopting this approach, which provides exploratory insight that would be difficult to obtain through other methods of research (Prencipe et al., 2014).

Accordingly, this study is based on an in-depth case study, with the main aim being to explore the role of MASs in family firms during the succession process, and to analyse the reasons for success in passing the business to later generations, focusing on the changes affecting organizational routines. This case study can be classified as explanatory (Scapens, 1990), as the empirical evidence is used to understand and explain the role played by the MAS within the succession process.

To achieve the goal of this study, documentation, archival records, internal reports, company history and physical artefacts have been used. Interviews are considered a data source because they are the main source of information (Saunders et al., 2007).

The study focuses on family relation dynamics, the firm’s history, and the system of management accounting used at Grotta del Sole. We selected this case study because Grotta del Sole is a typical family firm, based in the Campania region (south of Italy), which operates in one of the most relevant Italian industrial sectors: the wine industry. Even though winemaking is a traditional industry sector, it has had a wide and global renaissance, due to advances in science and technology which have largely improved the traditionally practice-based industry, at the same time increasing knowledge through formal education (Johnson and Robinson, 2007; Woodfield and Husted, 2017).

Italy is one of the largest wine producers in the world and in Europe, contending with France for first place. In ancient times, the best wines – Falerno, Greco, Faustiniano and Caleno – were made in Campania. This region boasts of a wide range of high-quality grape varieties, such as Falanghina, Greco di Tufo, Aglianico, Asprinio, which are descendants of the ancient varieties Vitis Hellenica, Aminea Gemina, etc. This heritage represents the great richness of Campania, characterised by registered designation of origin (D.O.C.) and registered and guaranteed designation of origin (D.O.C.G.) certifications. Although Campania is a small region, its lands, 70% of which are hilly, offer numerous production areas.

Grotta del Sole has five production areas: Phlegraean Fields, Irpinia, the Sorrento Peninsula, Vesuvius and the Agro Aversano. At the time of the interviews, the company had 120 hectares of vineyards, 13 of which were in outright company ownership, 29 in direct management and the rest cultivated by the company’s trusted partners, some of whom have worked with the firm for forty years. The direct production quota amounts to 42 hectares out of 120, that is, about 35%.

This firm is a perfect setting for exploring the role of management accounting during the succession process, since it has experienced several succession phases, passing through various stages of preparation, ending with the entrance of a new owner into the family business (De Massis et al., 2008). The company is in its third succession phase.

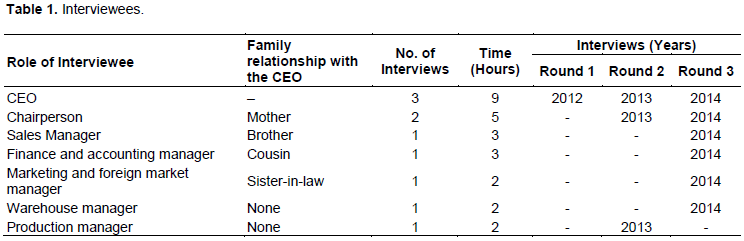

The data collection started with the chief executive officer (CEO) of the company. Later, the research group expanded the interviews with family members and employees from different departments. The research reconstructed a general picture of the firm; therefore, we have decided to detail the information focusing on the MAS and on the patterns of management accounting practices adopted during several life cycles of the business. In total, we collected 26 h of interviews in the course of three years (from 2012 to 2014; see Table 1). Reports have been checked and approved by the interviewed managers.

The research started with preliminary meetings with the CEO of Grotta del Sole (Francesco Martusciello), which provided background information regarding the firm. The following step involved other family and non-family managers, aiming at both obtaining other information on succession and introducing the role played by management accounting practices as well as their evolution through time (that is, in the second and the third generation). Finally, the last step involved several family managers, focusing on the main features of the MAS and the way they affected organizational routines, becoming ‘institutionalized.

In this way, the data and interviews were classified according to the steps of the succession process as well as the evolution of the role played by the MAS through time (that is, management accounting changes).

Succession in Grotta del Sole

The business at Grotta del Sole has existed since the 1930s (first generation) when Francesco Martusciello (senior) set up a small firm, Vinicola Flegrea, which was then managed by his three sons Angelo, Gennaro and Salvatore (second generation). Vinicola Flegrea bought and sold wine in bulk to local families and restaurants. The first succession phase (that is, from the first to the second generation) saw the growth of the company in terms of revenue and market share: Vinicola Flegrea became the first distribution company in the bulk wine market in Campania.

In the 1960s one of the three children, Gennaro, obtained a diploma in oenology in Conegliano (specialized in Italian prosecco, a type of sparkling wine) in the north of Italy and then a degree in agrarian sciences at Portici-Naples University, introducing the company to significant changes such as new production technologies (characterised by a greater automation) and the use of steel casks for wine storage. They installed 120 tanks of 150,000 hectolitres, with a turnover rate of three-fold per year, resulting in a profit of 13 billion Italian lire per year until the 1980s. Unfortunately, the methanol scandal of 1986 led to a period of crisis during which the company suffered a reduction in both turnover and profit margins. This crisis was worsened by resistance to the introduction of innovative managerial tools and practices, which were at that time based on manual procedures. As a result, management accounting was unable to give structured information about production costs and profit margins. In addition, there was an overlap between family roles and business roles.

My father Angelo daily put in writing inflows and outflows of each type of wine in the tanks; he adopted manual procedures to account for different prices of each purchase (inflow) with the objective of determining the average cost of wine in each tank, and then the average value of each sale (outflow). Periodically, my uncle Gennaro called together family members around a table to distribute profits, taking into account not so much the role of members in the business but primarily their role in the family (Francesco, CEO, Grotta del Sole).

Basically, they were unable to change their strategic vision to overcome the market crisis, inhibiting their innovative ideas such as the transformation of table wine into sparkling wine (spumante), which would play a key role in the product portfolio in the following years.

During this tough period, the heirs were involved in the operational activities of the company, and straightaway promoted new formal practices and small technological innovations. As a result, a positive discussion started in order to find solutions to this organizational impasse.

The new (that is, the third) generation, guided by Francesco (Angelo’s son) and supported by Elena Martusciello (Angelo’s wife), came up with the idea of starting a new business (in parallel with Vinicola Flegrea): Grotta del Sole. They set up a new production and bottling plant with a new brand. Thanks to this strategy, the business grew, as the diverse lines of business were progressively divided up in order to diversify the products for different specific segments of the market. The capital shares were split between Angelo (51%) and Salvatore (49%), while Gennaro, the eldest brother and the head of Vinicola Flegrea, did not receive any shares because he officially did not agree with the Grotta del Sole project.

According to Gómez-Mejía et al. (2001), one of the main sources of SEW is having the family name associated with the firm; Gennaro was therefore worried about the risk of losing the identification between the family and Vinicola Flegrea, especially on the part of external stakeholders. However, from another perspective, this was a forward-looking decision because the chosen model of governance prevented a probable organizational impasse (thanks to the 51% of shares owned by Angelo).

Nevertheless in Grotta del Sole, the older generation tried to replicate the same managerial model, giving Gennaro the technical and financial functions, while Angelo was in charge of sales and Salvatore was responsible for production and operations, even though they gave Francesco and the younger members the operative management of sales and other functions.

To advance Grotta’s business operations, Francesco and others introduced innovations such as new formal rules about salaries as well as the automation of the warehouse. The growth of the business and the resulting increased complexity required a greater formalization of its organizational structure. The leaders created a management accounting system based on financial targets and measures in order to control revenues, margins and cash flows.

The introduction of formal procedures in determining salaries represented a great change because Gennaro gradually lost the management of financial resources (he was used to distributing earnings during the family councils); in the same way, the introduction of an inventory accounting software, developed by Francesco in basic programming language, led to the abandoning of Angelo’s manual practices concerning the warehouse control.

My uncle Gennaro and my father Angelo considered a revolution these ‘small’ innovations that also facilitated the automation of internal accounting procedures, helping the external accountants to prepare the financial statements. As a matter of fact, these innovations gradually separated the two companies; the older generation played a marginal role in Grotta, while Gennaro, Angelo and Salvatore persisted in the old practices in Vinicola Flegrea (Francesco, CEO, Grotta del Sole).

Two main events accelerated the succession: the unexpected death of Angelo in 2001 and the closeout of Vinicola Flegrea from 2004 to 2006 (that had been continuing to work with inertia). The closeout determined the first significant conflict between Gennaro and the heirs, which intensified when the oenological choices were handed over to an external consultant.

Unfortunately, Gennaro fell ill in 2005. A younger member of the family started to run the family business in order to continue with the wine production. The grandson continued the innovation path of the family business, helped by his education in this field; indeed, he bore the title of graduate wine expert. A new generation with new qualifications opened new opportunities to the firm: Grotta started producing eighteen new varieties of wine, sold as multiple brands.

During this period, the company was reorganized: Francesco became CEO, and his mother Elena the Chairperson; his uncle Salvatore was appointed to logistics and sales, his brother Salvatore (jr) was appointed as sales manager and his wife Gilda was put in charge of marketing (especially for organizing touristic, oenological and gastronomic visits to the vinery) and international relations.

Management accounting changes at Grotta del Sole

As a matter of fact, when a family firm reaches the growth stage, which implies analytical decision-making style, growing market share, and product complexity, it is important to present information in a more aggregated and integrated way to be able to analyse situations and choose good strategies (Salvato and Moores, 2010). Francesco understood the need to control internal and external information, and on this basis he reorganized the retail network and sales areas with new marketing policies, new products and labels, and started to sell in foreign markets. Fifty sales agents, who made up the retail network, asked for daily updated reports and statistics about sales per client, types of product, geographical area, etc. Francesco introduced several innovations such as web-based application for selling activities, replacing old technologies, and opened the way for mobile and web services such as tablets and smartphones.

We decided to innovate not only the production process and internal organization but also marketing strategies. Our agents are using tablets as a promotional tool, which helps us to update sales statistics in real time. Moreover, it is possible to check the status of orders and the stock split on type of products, in order to optimise our delivery system (Francesco, CEO, Grotta del Sole).

The great revolution started in 2008 and continued until 2010. Francesco introduced an Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) information system to organize the management accounting practices. Furthermore, he linked a reporting system to the ERP, based on Oracle, to create reports based on accounting data and financial statement ratios. These new solutions supported the decision-making processes. Analytical information optimises the purchasing of raw materials and packaging materials and helps the firm to understand the real contribution of each type of grape to profits. This system details the production process costs and the gross margins for each type of grape. The introduction of these novelties was, of course, difficult, and Francesco had to face the resistance of Salvatore and other family members to using the new way of operating. Some of these innovations were considered as a risk of obscuring the external perception of the high quality of the Grotta del Sole products. Indeed, identifying the family with the firm implies, among other things, that family members are quite sensitive about the external image they communicate to stakeholders (Micelotta and Raynard, 2011).

The consistency of the bottle glass, produced to our requirements by craftsmen in Tuscany, was considered by our customers as a positive and distinctive characteristic of our products; therefore, it became one of the main competitive advantages of the company. When Francesco proposed to reduce the weight of the bottle (from 750g to 600g in order to reduce its unit cost, all the family members disagreed with his proposal. However, he showed a strong cost reduction with this small change, so we were encouraged to try… We had a lot of benefits (Elena, Chairman at Grotta del Sole).

Nevertheless, Francesco used the information provided by the ERP system to support his hypotheses and strategies during the family councils. The rise in revenue and market share, as well as the improvement of profit margins, persuaded the family members to the new management accounting practices and computer tools; since then, these practices have paved the way for new organizational processes and rules. According to Bertone et al. (2012), this would mean that preserving SEW does not necessarily imply sacrificing financial rewards.

The role of management accounting practices during the succession

Francesco, the CEO at Grotta del Sole, used this information to reinforce his leadership and guide the family councils. The organized accounting information facilitated the transmission of ideas, values and social interactions between family members and also employees (Nordqvist et al., 2013).

The new MAS provided the organization with more comprehensive decision support systems for increasing the decision-making authority. These new tools and rules greatly helped Francesco to manage the business with a long-lasting vision. A successful succession is often the result of employees’ positive perception and legitimation of the successor (Ibrahim and Ellis, 2004).

As a matter of fact, management accounting practices (and their changes) were gradually considered as a common language, making sense of activities, creating action plans and implementing them within the firm (Scapens, 1994). Old routines provided an organizational memory that embodied a potential resistance to change, corresponding to formalized and ‘institutionalized habits’. Step by step, organizations evolve, affecting management accounting practices that in turn gradually change over time, representing the ‘way of doing things’ (Burns and Scapens, 2000; Nelson and Winter, 1982).

Therefore, management accounting changes became a language for the knowledge transfer: the leader of the third generation used information to enforce his leadership and to explain the required strategy to maintain the firm’s competitive advantage on the market (Cherchem, 2017), while preserving SEW.

Sharma et al. (2003) explain how MASs reinforce the founder’s influence in the communication of future visions, values, and priorities that affect the process of succession; this can balance the commitment of the family to support strategic flexibility. In Grotta del Sole, it was evident that a common language and approved MASs facilitated internal communication and interaction developing a common vision for the business.

The succession process forces different significant changes on the family system: relationships are reshaped; patterns of influence are redistributed; organizational and ownership structures have a new configuration. According to Busco et al. (2006) and Giovannoni et al. (2014), management accounting practices, if they are widely accepted and practiced within the firm, can:

(1) Act as a carrier of organizational knowledge and

(2) Can transfer values and ideas of expected behaviour, through the process of social interaction that takes place around the same practice.

This means that, according to Ahrens and Chapman (2002), there is a strong link between ‘knowing’ and ‘doing’. In the case of Grotta del Sole, the high level of interaction characterising both the decision-making process and the way things were actually done facilitated the process of knowledge transfer between the family and non-family managers.

My father-in-law had the ability of memorising all the information concerning stock levels and deliveries. Furthermore, he was able of organizing oenological and gastronomic events and visits to the vinery without predisposing a programme. Nowadays, these events are part of a marketing strategy and are organized in a very accurate and punctual way (Marketing manager at Grotta del Sole).

When I started working at Vinicola Flegrea, with the older (i.e. the second) generation, I had a direct relationship with suppliers and on a daily basis I used to define deliveries according to informal procedures. The introduction of new formalised routines at Grotta del Sole, coupled with the availability of information on stock levels, has now simplified the work. For me, it was a great change and, initially, I was not confident about the new organizational routines, but now I am definitely aware of their benefits (Warehouse Manager at Grotta del Sole).

These changes provoke anxiety due to the uncertainties surrounding the future of the company that often overlap with life cycle changes in the family as well as with changes in the form of the market and the products. Additionally, these changes may have a devastating effect on both the business and the family if the transition is forced by the early death of the founder (Moores and Mula, 2000), as in the case of Grotta del Sole.

These uncertainties make it necessary to address many emotionally loaded issues that most people would prefer to avoid or deny (Lansberg, 1988). However, family and non-family managers, as well as employees, became more conscious of the company’s changing priorities and of the importance of having more punctual information regarding the business. As far as the new management accounting practices became a shared ‘language’ within the firm, family and non-family managers were provided with a set of categories that made sense of activities, at the same time improving communication and knowledge transfer (Roberts and Scapens, 1985). Furthermore, according to Woodfield and Husted (2017), this means that knowledge sharing in family firms leads to innovative outcomes and change.

Within Grotta del Sole, the new management accounting practices helped to integrate informal communication mechanisms in transmitting the strategic vision of Francesco, who used the generational jump as a trigger to rapidly replace old routines and institutions with more effective and efficient ones. He knew there was no strong reason to believe that routines would inevitably evolve in order to give the optimal choice, and what was deemed acceptable would have been influenced by the meaning and norms embedded in the ongoing routines and also the powers of individual actors. The succession represented both a problematic and an opportune moment, where it was required to take jointly into consideration the socio-emotional wealth of family members and the financial rewards of the company.

As Scapens (1994) argues, such changes involve renegotiating shared understanding of organizational activities and the suspension of intra-organizational conflict; that is, succession represents a mutual role adjustment process from one generation to the next. Francesco felt that management accounting tools and practices could enable organizational and decision-making activities to be passed from one generation to another. In this process of institutionalization and routine setting, the MAS played a central role. Francesco progressively used reports to influence and drive decision-making activities, and to generate a new understanding about company events.

Accounting practices mitigated the change and helped Francesco to justify his work and achieve organizational cohesion; accounting, in part, was responsible for curbing latent organizational conflicts. Family members felt that a truce in intra-organizational conflict had been reached. This was indeed one of their main (family) benefits (Hiebl et al., 2013) from MAS, which is related to its capacity to speed up the process of integrating the old and the new.

Moreover, the MAS in this case helped to transfer genuinely the decision-making power and business values to the new generation in due time. While in a first step there was a process of replication of previous routines (in the sense of Hodgson and Knudsen, 2004), step-by-step routines changed due to a selection: better control led to better decision making and action planning, also helping remove inefficiencies as well as a clear delegation of responsibilities to others. A shared understanding of roles and tasks also promoted internal role specialization.

When I started working at Grotta del Sole, I implicitly assumed organizational routines adopted by my father at Vinicola Flegrea (especially the centralization of all the sales and warehouse decisions) as a benchmark. However, my brother Francesco progressively convinced me to abandon them, adopting decentralization as a ‘golden rule’. The data he showed us during our family councils provided evidence that his approach was correct. This implied a progressive but constant reorganization of our activities, therefore we promoted internal role specialization (Sales Manager at Grotta del Sole).

From another perspective, clear and informed communication brought a high level of trust that served as a governance tool (ownership benefits; Hiebl et al., 2013). Family councils, as well as formal and informal meetings to discuss issues and increase interaction among members, represented the main institutionalized routine that Francesco used in order to share the vision and the future of the firm in terms of growth rates and company performance (business benefits; Hiebl et al., 2013).

Financial and economic values, gained through the MAS, were at the heart of discussions and forged a shared view of the goals of the company (Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998). This starts a virtuous cycle: the analysis of a large amount of data requires a shared vision in order to focus on relevant issues; consequently, richer information reduces opportunism and this leads to further increases in the amount of information shared.

Furthermore, this progressively reinforced the link between the family and company, allowing for achievement of both the socio-emotional wealth and the financial rewards. Accordingly, a selection of routines resulted from internal managerial action, due to perceptions of the relative inefficiency of the old routines (Becker, 2004). The performance indicators do not represent just a set of measures but embrace the vision of Francesco. Both family and non-family managers seem to have understood this.

CONTRIBUTIONS AND FURTHER DEVELOPMENTS

The recent literature reviews on accounting and family business (Salvato and Moores, 2010; Songini et al., 2013; Prencipe et al., 2014) call for more research on management accounting–family business interface. Scholars highlight that there is a need to provide new insight, among other things, on the role that management accounting can play during the succession process.

This study responds to these calls, investigating the determinants of succession-planning activities in family firms, in particular the positive relation between using an MAS and the success of the transition phase. This study provides evidence of the role of MAS in helping the succession process from the second-generation members to the third, in establishing the leadership of the firm, in helping the family decision-making process (in the new setting) and in implementing new routines.

The successor, to move from one stage to another during the succession process, works on changing patterns of behaviour, that is, routines. To change these routines, the successor in this instance introduced a new MAS, based on new tools and practices, in order to introduce a different managerial approach and to gain the leadership of the company.

The new leader guided the succession from the second to the third generation in both a revolutionary and an evolutionary way. Revolutionary changes occur when the existing routines are drastically modified, while evolutionary changes affect, but do not disrupt, the existing routines (Burns and Scapens, 2000; Nelson and Winter, 1982). Grotta del Sole represented a drastic (revolutionary) change: the leader of the third generation, with the support of some family members of the old one, showed long-sightedness in starting a new business in parallel with the old one (Vinicola Flegrea). In this way, the leader of the new family firm was able to introduce other (evolutionary) changes; accordingly, the process of routinization spurred the evolution of institutions, imposing new social habits upon people. Through both formal meetings and family councils, the successor enacted the existing rules and routines, forcing meanings and values to change. This process facilitated the renegotiations of shared understanding of organizational activities and suspended the intra-organizational conflicts, with an effective change in leadership.

Additionally, the study findings highlight that combining SEW and financial outcomes cannot be easy, at the same time emphasising that gaining a proper balance between emotions and facts in supporting the decision-making process could better support the transition from one generation to another. Indeed, this balance could allow family firms to achieve both family and business benefits, consistently with the model of Hiebl et al. (2013): on one hand, family members progressively understand the importance of avoiding intra-organizational conflict; on the other hand, MAS could accelerate the process of integrating the old and the new.

Therefore, findings from this study highlight how relevant a revolutionary change could be in facilitating the succession from one generation to another as well supporting the emerging leadership. Additionally, the study findings point out that, while studying management accounting changes, several aspects regarding the organizational activity would deserve attention. In the investigated case, the decisions concerning the governance structure of Grotta del Sole would have had a great impact on the implementation of new strategies as well as on the introduction of new practices and tools, de facto preventing probable organizational impasses: according to Handler and Kram (1988), power imbalances and maintenance of structures promoting unilateral controls can incite resistance to a successful succession.

These changes facilitated the progressive introduction of new management accounting practices: the MAS adopted by the new generation represent a clear example of how actors manage the change by altering routines and introducing varied routines (definitely new or modified). During family councils and the decision-making process, values and meanings are structured and shared through discussions on accounting data, involving all the family members. This means that sharing knowledge and having an informed communication, mainly through family councils interpreted as a governance tool (ownership benefits; Hiebl et al., 2013), lead to a high level of trust between family members.

This means that the introduction of new management accounting practices and tools is not a mere diffusion of formal competence; according to Giovannoni et al. (2011), it should be considered as a process of transfer of cultural competence (Cherchem, 2017). Therefore, the importance of a shared language in transferring knowledge, visions, strategies and behaviours to different groups of individuals should be clear. We learned the potency of MAS in leveraging succession because the process is primarily an emotional and value issue (Hess, 2006).

The literature strongly emphasises that decisions seem to be made because of situational obligations and not as a genuine desire of incumbents to manage or control the family business. For these reasons, we delineated the factors behind the succession process of family-owned businesses by investigating the entry mode of successors and the importance of MASs in analysing the position of the firm and deciding the right strategies to adopt.

To recapitulate, this study has contributed to the debate on management accounting systems and succession (Amat et al., 1994; Giovannoni et al., 2011; Hiebl et al., 2013) by shedding fresh light on the role of four intertwined elements:

1. The generational jump is used as a trigger to change routines and institutions; the specific context required a revolutionary change gained through the setting up of a new company – Grotta del Sole.

2. Revolutionary changes are expected to cause several problems regarding the effectiveness of the change itself and tools useful for its management. Therefore, renegotiation of shared understanding of organizational activities and the suspension of intra-organizational conflicts are required. This would mean linking the family business succession to both external triggers and changes in organizational routines (Nigam et al., 2016).

3. Management accounting practices can mitigate the changes, enabling family firms to achieve organizational cohesion in the succession process. More specifically, management accounting plays a part in controlling and channelling actual and latent organizational conflicts while institutionalizing routines and, at the same time, facilitating achievement of a balance between socio-emotional wealth and financial rewards (Berrone et al., 2012).

4. Management accounting change processes, supporting the transfer of knowledge, can be considered as inextricably linked with the succession process, which implies the transfer of expertise, knowledge and ideas (Cabrera-Suarez et al., 2001; Perricone et al., 2001).

We would argue that these elements could be taken into account while planning a transition from one generation to another, especially in the case of small family firms and/or when a change in leadership is needed.

This study suffers from some limitations. Firstly, further studies could be focused on investigating the transfer of knowledge (Cunningham et al., 2017) in both explicit and tacit (uncodifiable) ways (Hansen, 2002). Additionally, there is room for future research in exploring deeper into the role of macro pressures from outside the firm, which can affect the processes of institutional change. From a theoretical perspective, this would mean ‘exploring the processes of institutional change through a combination of ideas from both old institutional economics and institutional sociology’ (Scapens, 2006). This could support a broader perspective, going beyond the boundary of the family business field by investigating, for example, processes of professionalization coupled with processes of management accounting changes in small firms during their life cycles.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Ahrens T, Chapman, CS (2002). The structuration of legitimate performance measures and management: Day-to-day contests of accountability in a UK restaurant chain. Man. Acc. Res. 13:151-171.

|

|

|

|

Ahrens T, Chapman, CS (2006). Doing qualitative field research in management accounting: Positioning data to contribute to theory. Acc. Org. Soc. 31:819-847.

|

|

|

|

|

Ahrens T, Chapman, CS (2007). Management accounting as practice. Acc. Org. Soc. 32, 1-27.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Allio MK (2004). Family businesses: Their virtues, vices, and strategic path, Strat. Leader. 32(4):24-33.

|

|

|

|

|

Amat J, Carmona S, Roberts H (1994). Context and change in management accounting systems: A Spanish case study. Man. Acc. Res. 5:107-122.

|

|

|

|

|

Aronoff CE, Astrachan JH, Ward JL (2010). Family business sourcebook, 3rd edition, Family Enterprise Publishers.

|

|

|

|

|

Astrachan J, Shanker M (2003). Family Businesses' Contribution to the US Economy: A Closer Look. Fam. Bus. Rev. 16(3):211-219.

|

|

|

|

|

Becker MC (2004). Organizational routines: a review of the literature. Ind. Corp. Change, 13(4):643-677.

|

|

|

|

|

Berrone P, Cruz C., Gomez-Mejia LR (2012). Socioemotional Wealth in Family Firms: Theoretical Dimensions, Assessment Approaches, and Agenda for Future Research. Fam. Bus. Rev., 25(3):258-279.

|

|

|

|

|

Bird B, Welsch H, Astrachan JA, Pistrui D. (2002). Family business research: the evolution of an academic field. Fam. Bus. Rev. 15(4):337-350.

|

|

|

|

|

Bisogno M, Nota G, Saccomanno A, Tommasetti A. (2015). Improving the efficiency of Port Community Systems through integrated information flows of logistic processes. Int. J. Digital Acc. Res. 15:1-31.

|

|

|

|

|

Brockhaus RH (2004). Family business succession: suggestions for future research. Fam. Bus. Rev. 17(2):165-177.

|

|

|

|

|

Burns J, Scapens RW (2000). Conceptualizing management accounting change: an institutional framework. Man. Acc. Res. 11:3-25.

|

|

|

|

|

Busco C, Riccaboni A, Scapens RW (2006). Trust for accounting and accounting for trust. Man. Acc. Res. 17:11-41.

|

|

|

|

|

Cabrera-Suarez K, Saa-Perez de P, Garcia-Almeida D (2001). The succession process from a resource-and knowledge-based view of the family firm. Fam. Bus. Rev. 14(1):37-48.

|

|

|

|

|

Cater III JJ, Kidwell RE, Camp KM (2016). Successor Team Dynamics in Family firms. Fam. Bus. Rev. 29(3):301-326.

|

|

|

|

|

Cherchem N (2017). The relationship between organizational culture and entrepreneurial orientation in family firms: Does generational involvement matter? J. Fam. Bus. Strat. 8(2):87-98.

|

|

|

|

|

Chrisman JJ, Chua JH, Sharma P (2005). Trends and directions in the development of a strategic management theory of the family firm. Entrep. Theory Pract. 29:555-575.

|

|

|

|

|

Churchill NC, Hatten KJ (1987). Non-market-based Transfers of wealth and power: a research framework for family businesses. Am. J. Small Bus. 11(3):51-64.

|

|

|

|

|

Churchill NC, Lewis VL (1983). The five stages of small growth. Harv. Bus. Rev., May-June. pp. 30-51.

|

|

|

|

|

Cunningham J, Searman C, McGuire D (2017). Perceptions of knowledge sharing among small family firm leaders: a structural equation model. Fam. Bus. Rev. 30(2):160-181.

|

|

|

|

|

Davis PS, Haverston PD (1998). The influence of the family on the family business succession process: A multi-generational perspective. Entrep. Theory Pract. pp. 31-53.

|

|

|

|

|

De Massis A, Kotlar J (2014). The case study method in family business research: Guidelines for qualitative scholarship. J. Fam. Bus. Strat. 5:15-29.

|

|

|

|

|

De Massis A, Chua JH, Chrisman JJ (2008). Factors preventing intra-family succession. Fam. Bus. Rev. 21(2):183-199.

|

|

|

|

|

Gersick KE, Davis JA, McCollom-Hampton M, Lansberg I (1997).

|

|

|

|

|

Generation to Generation: Life cycles of the family business, Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

|

|

|

|

|

Gilmore RN, McCann JE III (1983). Designing Effective Transitions for New Correctional Leaders, In J. W. Doig (eds.), Criminal Corrections:

|

|

|

|

|

Ideals and Realities. Lexington, V a.: Lexington Books.

|

|

|

|

|

Giovannoni E, Maraghini MP, Riccaboni A (2011). Transmitting Knowledge Across Generations: The Role of Management Accounting Practice. Fam. Bus. Rev. 24(2):126-150.

|

|

|

|

|

Goldberg SD, Wooldridge B (1993). Self-Confidence and Managerial Autonomy: Successor Characteristics Critical to Succession in Family Firms. Fam. Bus. Rev. 6(1):55-72.

|

|

|

|

|

Gómez-Mejía LR, Nunez-Nickel M, Gutierrez I (2001). The role of family ties in agency contract. Acad. Man. J. 44:81-95.

|

|

|

|

|

GoÌmez-Mejia LR, Nunez-Nickel M, Jacobson KJL, Moyanao-Fuentes J (2007). Socioemotional wealth and business risks in family-controlled firms: Evidence from Spanish olive oil mills. Admin. Sci. Quar. 52:106-137.

|

|

|

|

|

Gordon GE, Rosen N (1981). Critical Factors in Leadership Succession. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perf. 27:227-254.

|

|

|

|

|

Gottardo P, Moisiello AM (2017). Socioemotional wealth and probability of financial distress. Afr. J. Bus. Manage. 11(3):285-292.

|

|

|

|

|

Greiner LW (1972). Evolutions and revolutions as organizations grow. Harvard Business Review, July-August. pp. 37-46.

|

|

|

|

|

Hall PD (1988). A historical overview of family firms in the United States. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1(1):51-68.

|

|

|

|

|

Handler WC (1994). Succession in Family Business: A Review of the Research. Fam. Bus. Rev. 7(2):133-157.

|

|

|

|

|

Handler WC, Kram KE (1988). Succession in Family Firms: The Problem of Resistance. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1(4):361-381.

|

|

|

|

|

Handler WC (1990). Succession in family firms: A mutual role adjustment between entrepreneur and next-generation family members. Entrep. Theory Pract. 15(1):37-51.

|

|

|

|

|

Handler WC (1992). The succession experience of the next-generation. Fam. Bus. Rev. 5(3):283-307.

|

|

|

|

|

Hansen MT (2002). Knowledge networks: Explaining effective knowledge sharing in multiunit companies. Org. Sci. 13:232-248.

|

|

|

|

|

Hesford JW, Lee SH, Van der Stede WA, Young SM (2007). Management Accounting: A bibliographic study, In Chapman CS, Hopwood AG, Shields MD (eds). Handbook of Management Accounting Research, Boston: Elsevier. pp. 3-26.

|

|

|

|

|

Hess DE (2006). The successful family business, London: Praeger.

|

|

|

|

|

Hiebl MRW (2013). Management accounting in the family business: tipping the balance for survival. J. Bus. Strat. 34(6):19-25.

|

|

|

|

|

Hodgson GM, Knudsen T (2004). The firm as an interactor: firms as vehicles for habits and routines. J. Evol. Econ. 14: 281-307.

|

|

|

|

|

Hollander BS, Elman NS (1988). Family-owned businesses: An emerging field of inquiry. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1(2):145-164.

|

|

|

|

|

Hopwood A (1983). On trying to study accounting in the contexts in which it operates. Acc. Org. Soc. 12:207-234.

|

|

|

|

|

Hopwood A (1990). Accounting and organisation change. Acc. Aud. Account. J. 3:7-17.

|

|

|

|

|

Ibrahim AB, Ellis WH (2004). Family Business Management: Concepts and Practice, 2nd edition. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt.

|

|

|

|

|

Johnson H, Robinson J (2007). The world atlas of wine. London, England: Mitchell Beazley.

|

|

|

|

|

Kansikas J, Kuhmonen T (2008). Family Business Succession: Evolutionary Economics Approach. J. Enterprising Culture 16(3):279-298.

|

|

|

|

|

Kets de Vries MFR (1985). The dark side of entrepreneurship. Harv. Bus. Rev. November–December. pp. 160-167.

|

|

|

|

|

Klein S (2000). Family Businesses in Germany: Significance and Structure. Fam. Bus. Rev. 13(3):157-181.

|

|

|

|

|

Lansberg IS (1988). The Succession Conspiracy. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1(2):119-143.

|

|

|

|

|

Leppäaho T, Plakoyiannaki E, Dimitratos P (2016). The case study in family business: An analysis of current research practices and recommendations. Fam. Bus. Rev. 29(2):159-173.

|

|

|

|

|

Longenecker JG, Schoen JE (2002). Management succession in the

|

|

|

|

|

family business, in Aronoff CE, Astrachan JH, Ward J (eds.), Family business sourcebook, 3rd edition, Family Enterprise Publishers. pp. 61-66.

|

|

|

|

|

Micelotta E, Raynard M (2011). Concealing or revealing the family? Corporate brand identity strategies in family firms. Fam. Bus. Rev.

|

|

|

|

|

24:197-216.

|

|

|

|

|

Moores K, Mula J (2000). The Salience of Market, Bureaucratic, and Clan Controls in the Management of Family Firms Transitions: Some Tentative Australian Evidence. Fam. Bus. Rev. 13(2):91-106.

|

|

|

|

|

Nahapiet J, Ghoshal S (1998). Social Capital, Intellectual Capital, and the Organizational Advantage. Acad. Man. Rev. 23(2):242-266.

|

|

|

|

|

Nelson RR, Winter SG (1982). An evolutionary Theory of Economic Change. Harvard University Press.

View

|

|

|

|

|

Nigam A, Huising R, Golden B (2016). Explaining the Selection of Routines for Change during Organizational Search. Admin. Sci. Quart. 61(4):551-583.

|

|

|

|

|

Nordqvist M, Wennberg K, Bau M, Hellerstedt K (2013). An entrepreneurial process perspective on succession in family firms. Small Bus. Econ. 40(4):1087-1122.

|

|

|

|

|

Nordqvist M, Zellweger TM (2010). Transgenerational Entrepreneurship, Cheltenham – Northampton: Eldward Elgar.

|

|

|

|

|

Perricone PJ, Earle JR, Taplin IM (2001). Continuity in family-owned businesses: study of an ethnic community. Fam. Bus. Rev. 14(2):105-122.

|

|

|

|

|

Prencipe A, Bar-Yosef S, Dekker HC (2014). Accounting Research in Family Firms: Theoretical and Empirical Challenges. Eur. Acc. Rev. 23(3):361-385.

|

|

|

|

|

Roberts J, Scapens RW (1985). Accounting systems and systems of accountability: Understanding accounting practices in their organizational context. Acc. Org. Soc. 10:443-456.

|

|

|

|

|

Ryan B, Scapens RW, Theobold M (2003). Research method and methodology in finance and accounting, 2nd edition, Thomson Learning, London.

|

|

|

|

|

Salvato C, Moores K (2010). Research on Accounting in Family Firms: Past Accomplishments and Future Challenges. Fam. Bus. Rev. 23(3):193-215.

|

|

|

|

|

Saunders M, Lewis P, Thornhill A (2007). Research Methods for Business Students, 4th ed., London, FT Prentice Hall.

|

|

|

|

|

Scapens RW (1990). Researching management accounting practice: the role of case study methods. British Acc. Rev. 22:259-281.

|

|

|

|

|

Scapens RW (1994). Never mind the gap: toward an institutional perspective on management accounting practice. Man. Acc. Res. 5:301-321.

|

|

|

|

|

Scapens RW (2006). Changing time: Management accounting research and practice from a UK perspective, in Bhimani A (eds.), Contemporary issues in management accounting, Oxford University Press. pp. 329-354.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Schein EH (1983). The role of the founder in the creation of organizational culture. Organ. Dynamics 12:13-28.

|

|

|

|

|

Schein EH (1985). Organizational culture and leadership, San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

|

|

|

|

|

Shanker MC, Astrachan JH (1996). Myths and realities: Family businesses' contribution to the US Economy - A framework for assessing family business statistics. Fam. Bus. Rev. 9(2):107-123.

|

|

|

|

|

Sharma P, Chrisman JJ, Pablo A, Chua JH (2003). Succession Planning as Planned Behaviour: Some Empirical Results. Fam. Bus. Rev. 16(1):1-15.

|

|

|

|

|

Shepherd DA, Zacharakis AL (2000). Structuring family business succession: An analysis of the future leader's decision making. Entrep. Theory Pract. 24(4):25-39.

|

|

|

|

|

Songini L, Gnan L, Malmi T (2013). The role and impact of accounting in family business. J. Fam. Bus. Strat. 4:71-83.

|

|

|

|

|

Ward JL (1987). Keeping the Family Business Healthy. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

|

|

|

|

|

Woodfield P, Husted K (2017). Intergenerational knowledge sharing in family firms: Case-based evidence from the New Zealand wine industry. J. Fam. Bus. Strat. 8:57-69.

|

|