South Africa has its own texture of cultural diversity unparalleled by any in the history of the world. The diversity emanates from the period of the Dutch settlers (1640s) occupying land in the country through their by conquest of the non-militant indigenous inhabitants. Soon the British arrived (1800s) and occupied more land. Before long, the two settler groups were fighting for ownership and control of the land. As soon as their conflict was resolved, the Dutch settlers now started a program of separate development by removing the indigenous people from fertile land to Bantustans. The result therefore was an uprising of the people culminating in the democracy gained in 1994, thereby bringing to an end an error of inhuman treatment in which the whites were and are still the beneficiaries. South Africa today has twelve language groups (official 11 because for no known reason the Khoisan have been excluded), and all these people meet in the workplace. The arrival of other Europeans, Africans and Asians as economic refugees has not made the situation better. The South African landscape is now more diverse than ever and this is reflected at the workplaces creating a need for diversity management. This paper focuses specifically on identifying the extent to which the managers are aware and prepared to manage culturally diverse environment. Whilst there is continued assertion by managers that they know enough about the other cultures, there is unprecedented neutrality to pertinent questions and statements dealing with the subject. The finding is that the managers who are largely white and coloured have not taken enough pain to understand and accommodate the majority 80% black who are the indigenous inhabitants.

The independence of South Africa marked by the rule of the country by the indigenous blacks meant the demise of the apartheid’s separate development philosophy which kept people apart from each other by race. The advent of black rule ushered in another error bringing more diverse groups to work together as equal before the law. It cannot be denied that the presence of black rule never meant sudden change on the leadership guard in the industry.

The previous beneficiaries of separate development continue in control of the economy with little change in ownership in the private sector. Much of any change took place in the government and parastatals, with the introduction of women who had been excluded from the previous error. The new dynamic was the sudden emergence of diverse people having to work together (Abdul-Aziz et al., 2014: 203-212), live together and manage together, theoretically at least. Immediately there was a sudden inflow of business opportunist and economic refugees largely from Africa, Asia and Europe joining the scramble for the small cake. This ushered in a very diverse environment which overwhelmed most managers and took them by surprise. Today South Africa has a diverse workplace defined by colour, tribe, ethnicity, language, religion and difference in education. Rukumba (2016: 47-53) defines diversity as all the ways or manners in which individuals differ.

Background to the study

In the South African context, the traditional definition of diversity has always been based on the race, culture and religion. People were easily classified according to how they look since these are the first physical features that would distinguish you from the other individual. Race was therefore synonymous with culture, and race also determined your salary and consequently your lifestyle. Whilst age, gender and disability were recognised, the broad classification was your race which determined your pay cheque and hence your lifestyle. The rest of the differences would be as variety within the major racial classification. The broader definition of diversity is inclusive and more elaborate; “all the ways in which people differ” (George and Jones, 2006: 115). Berger et al. (2018: 155-174) define diversity as variations among individuals due to age, gender, race, origin, religion, socioeconomic background, education, experience, physical appearance, and any other characteristic used to distinguish between people.

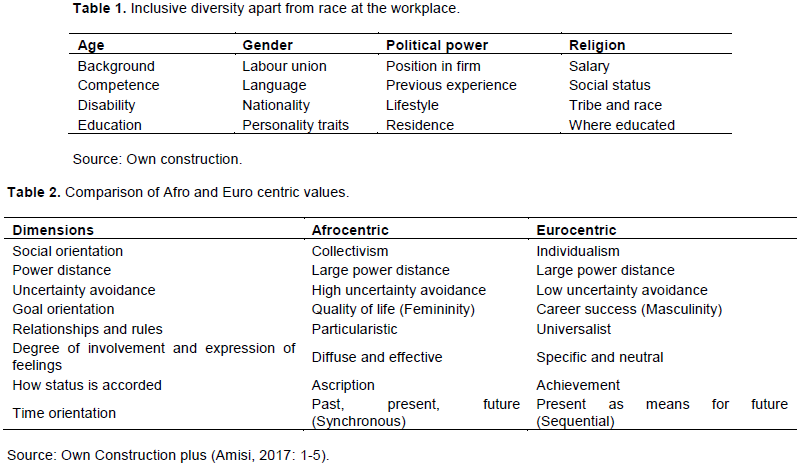

The inclusive definition of diversity brings in new complications and creates much smaller groups that may be difficult to manage at the workplace. The first problem the manager would encounter is knowing pretty well that they do not belong to the other groups and yet they are expected to work with them. Inclusive diversity is shown in Table 1.

Culture as the chief determinant of behaviour

Culture is defined and /or understood differently in the South African context, largely depending on who is considering culture. The large majority of people see race as culture, and the individual behaviour is always associated with culture of that racial group. Culture is a “set of key values, beliefs, understandings, and norms’ shared by a group of people (Daft, 2010: 76; Rukumba, 2016: 47-53) either as a community or an organisation. No one is born with a culture; rather people are born into a culture in which case they learn about the values and beliefs through instruction or observation. Rijamampianina and Carmichael (2005: 109-117) and Mavunga and Cross (2017: 303-326) posit that culture is observable in three layers, which are, namely; the visible, the invisible and the assumed layers of which these inform our behaviour. The visible comprises the way we look at race, colour of skin, type of hair and possibly dress which involves religion or spiritual beliefs. The invisible are those that cannot be seen on the individual but are interpreted by the observer based on; conduct, the way we respect, how we greet, the power play, team spirit and loyalty. The assumed are largely what other people perceive about your culture building to stereotypes, biases and opinions about a certain group. These are too often based on experience with individuals, stories told, etc.

Whilst there are so many issues that make us diverse from one another, the single most aspect that distinguishes us from each other is the race. The South African context is unique in that race also determines whether one is intelligent enough or able to lead and perform certain functions. The apartheid system taught that white equals intelligent, hardworking and able to manage whereas black equals lazy, incompetent and not able to manage. Koole et al. (2001: 289-301) and Kokolakis (2017: 122-134) posit that human behaviour is based on a sense of belonging and that their behaviour, feelings, and attitudes are influenced by their past, present and how they perceive future interactions with other people to be. It is therefore easier to associate along racial lines, though apartheid is now illegal; you may not be able to change the deep-seated belief based on the colour of one’s skin. These differences may affect the styles that are adopted by leaders from the different centricisms.

Table 2 shows Hofstee’s assertions on these differences. The differences in the values depicted in Table 2 create prospects for conflicts, given the previous segregationist policies with their effects. People therefore live in segregated communities largely, and the only place they meet is the work place. Working together is not an option, but an imperative for economic, legal and political reasons. The diverse group in the workplace has different expectations, and results in the powerful being the winners; this leads to ethnocentricism.

Problem statement

Because of the diverse nature of the workplace, it is understood that people will want to relate more with those that are similar to them. On the other hand, the brutal reality is that all people involved in the workplace contribute to the overall performance of the organisation. Everyone participating wants to be appreciated and acknowledged on their contribution which is largely influenced and informed by who they are. The differences in the basic cultural structures between the Afro and Euro centric approaches become an important issue because of both; the combination of the staff compliment and the economic benefit of diversity. The government also has its own expectations as it seeks to redress the economic imbalances of the past caused by the ill-informed philosophy of separate development policies. The question therefore arises as to what-centric may be ideal for effective productivity in a country already so low in its productivity? The research sought to identify the major differences and identify those elements of leadership inherent in the two systems to enable the construction of an industry relevant leadership style.

The findings are reported in a systematic way; the question is asked as it appeared in the questionnaire, and the response follows in the form of a comment, diagram or table for every question. The questionnaire was divided into three parts, namely, Section A was on the demographics of the respondents; Section B, was the content questions or statements relating to the content of the study itself; and Section C was for open ended questions to allow respondents to state any other information they may have perceived to be relevant. It is important to mention here that the official demographics as used by the Cape Town City Council for planning is in the ratio of 1 Indian: 12 whites: 25 blacks: 31 coloureds.

Section A: Demographics

This section was meant primarily to provide insight into the type of people who were responding in terms of their ethnicity, managerial function, background and other such information as would assist in qualifying the respondents for the survey.

Question 1: What is your ethnic group?

The respondents were expected to choose the most appropriate based on how they are classified. The study is essentially on the different race-centric management styles; hence this question was important to start with. This would enable the researcher later to analyse the information based on the demographics of the respondents in the industry. Figure 1 provides details of the response to this question.

The distribution of the responding population was 34% coloureds, 30% whites and 28% blacks with 4% Indians and 4% other. The responses showcase that the interviewees are from many different ethnic groups. It is evident that whites are disproportionately represented in management positions if comparison was to be made with the population ratios for the metropolis. The ratio is indicated earlier.

Question 2: How diverse is the staff compliment you manage?

It was necessary to see the extent of diversity in the structures. This would enable us to understand if there were any diversity challenges faced by the respondents. This would also determine if the respondents were relevant to the study. Table 3 provides the details of the responses.

According to the study, 63% workers are racially/ ethnically diverse, 17% for religious diversity, 13% considered elderly and sexual orientation at 7%. It should be noted also that apart from racial diversity, the rest are mutually inclusive and do overlap. As alluded to the aforementioned, race is the single most critical determinant of diversity in South Africa.

Question 3: Are you aware of the cultural diversity within your community?

The workplace is a microcosm of the society, but not always so in Cape Town. To date, there are residential areas where people live exclusively without racially diverse neighbours. University students coming from these areas meet for the first time students or lecturers of other races. The response to this question is reported as follows: 90% of the participants indicated awareness of the different societal cultures and backgrounds. It is not clear whether community here referred to the society in general or the community in which they lived. The remaining 6% are not aware and 4% have not noticed cultural diversity in their community. It can be generalized that the majority of the management are aware of cultural diversity in one form or another.

Question 4: Are you aware of cultural diversity within your work environment?

This question made reference to the workplace specifically which the research is focused on; it is here that the Afro and Euro centricism interact and collide. The response was largely as expected though there are a handful who did not see the diversity.

A good 94% (47 out of 50) of the respondents are aware of cultural diversity within the workplace, with 4% not having noticed and 2% not being aware. The 94% can be compared with the 90% in the previous question, allowing us to generalize that managers know about diversity in the workplace. What is important however is how much they know about the diversity and whether they have made any efforts to manage this diversity.

Question 5: Do you understand the differences caused by the diversity?

It is one thing to know about the presence of cultural

diversity and yet another thing to understand the diversity. Understanding the diversity may involve having to learn, mix and read about the other cultural values, if there is to be a meaningful comprehension of the different value and belief systems. Table 4 provides details of the responses. 68% fully understand the difference in their race/ethnic diversity, but it is not clear to what extent. 30% partly understand and 2% are not aware. There is no one that does not understand the differences. Exactly the same response was provided for religious and spiritual diversity.

Question 6: How do you determine the level of respect towards the elderly?

In the African culture it is disrespectful to call an individual older than you by their first name without putting a suffix or title. In the white culture there is little consideration for age: a black grandfather will be called by his first name by a 10-year-old boy. To the extent such an old man will be called a garden boy.

Results show that age has been given a 74% response followed by authority at 16%, 10% felt that the level of respect is determined by family relation while 0% of the interviews had a perception of race as some level to determine respect towards others.

Section B: Content response

This section is derived from the literature used for the background to this survey; the response to the statements is measured on a 5-level Likert scale. The response to each statement is supported by a bar chart, histogram, graph or any other physical illustration that makes it easy to make comparisons.

Statement 1: The good of the community must take precedence over rights of individuals

This is stated clearly by Hofstede in reference to the white culture based on individualism as opposed to the Afro-centric collectivism. The African mentality is based on “botho” values that state that “you are who you are because of other people.” Contrary to the Euro-centric philosophy based on individual success, Table 5 details the responses.

Statement 2: It is natural that some people should lead and others follow

Leadership is understood to follow naturally, but in the Afro-centric approach the elders reserve the right to lead to some degree. This does not translate to an absolute right, but young men are given to lead in place of the elderly who are presumed wiser than the younger. In the Euro-centric approach individuals compete to take up leadership roles.

Results show that the majority of 54% strongly agreed that it is inevitable and natural that some people will lead while others will follow, and 38% agreed giving a total of 92% in agreement. There is no disagreement on the need for leaders in both cultures, the difference may be on how a leader is chosen and for what functions. For the purposes of traditional roles, the eldest is always chosen, but the same may pass it on to a junior.

Statement 3: Traditions must be respected and followed including lessons of the past

Tradition has always been confused with customs and culture. Tradition is a belief or behavior based on the past and with symbolic meaning of some significance to the group. Common tradition in the previous structures was based on the discriminatory practices where blacks would never be managers.

Results show that 6% disagreed with maintaining of traditions and benefiting from lessons of the past. Ambivalence is at 10%, while 84% agreed. It is not clear since there was no specific mention of what traditions; these may not relate specifically to leadership styles.

Statement 4: There is a need for increased training in cultural diversity

Though 68% of the people responding to Table 4 indicated that they understand the cultural diversity well; training in cultural diversity should be an ongoing exercise. Until the managers are able to speak the language of their subordinates, meet the subordinates in their own ‘home ground’ it may not be possible to understand the culture. The responses to this statement are depicted next.

A total of 22% disagree with the need for increased training when 50% think it is necessary to increase the training in diversity. Of particular interest is the high 28% of managers with no opinion about this statement. 68 and 30% had indicated that they understand the cultural diversity fully and somewhat, respectively. This may be the cause for no interest in the increase on training in this regard; alternatively they may have been involved in the training.

Statement 5: I will attend a cultural diversity workshop if one is conducted in my area

Bringing this to one’s area might mean convenience and possibly encourage the managers to attend. Their opinions about extended education programs on diversity were intended primarily to enable them to manage cultural diversities more effectively.

As the results indicate, no one strongly disagreed (0%), and 6% disagreed with 36% remaining neutral. In agreement was a total of 58% of those who would attend. This should be compared with the 50% who would prefer that there should be increased training on cultural diversity.

Statement 6: I would participate in group discussion on cultural diversity?

This question sought to try and establish the extent to which these managers are interested in cultural diversity as a management problem. Any manager working in such culturally diverse environment and who believes that diversity may create synergy (high productivity) and conflict (low productivity) would invest in this area of management. Table 6 provides the details of the responses.

Table 6 shows that 10% disagreed, 30% were neutral, and 60% agreed. It can be generalized that managers would be prepared to participate in discussions on cultural diversity. Those that do not want to participate or are ambivalent about participating may be the ones who have problems with culture differences and may be ethnocentric.

Statement 7: I can mentor a culturally diverse management trainee

This would be more directly affecting the managers if they would have to train one individual different from them. It is assumed that managers interested in cultural diversity may want to take up this challenge to develop their management and leadership skills.

Results show that 30% of managers are neutral, 46% agree, and 24% disagree. These results are disappointing. It would appear that fewer managers are prepared to mentor someone of a different culture from theirs; this may indicate the racist attitude of the management in Cape Town metropolis.

Statement 8: Cultural diversity is used during performance appraisal

The context in which performance is always perceived has more to do with perceived similarities between the evaluator and the evaluated. Needless to say that the culture of the evaluator is used as a standard to determine what performance should be, except where clearly defined and evaluable activities are set. Apart from the differences in perceptions about measuring performance, there is also an element of interrelationships between the two people involved in the activity. Table 7 provides details of the responses to this statement.

Respondents (56%) believe that cultural differences are used for performance appraisal in many instances. Only 14% believe that it is used to a large extent with 30% thinking that cultural diversity is never used at all. It may be difficult to know if the disputed performance feedback is the actual measure of one’s inability to perform. It should be stated that by and large performance appraisal is very subjective.

Statement 9: Culture based conflicts are rare at my work place

This statement sought to identify if there were known conflicts directly related to cultural differences at the workplace. Culture based conflicts are clandestine and may surface in other issues instead. 44% of the respondents indicated no cultural conflicts - employees ignored the differences. 40% indicated open discussion on these differences to create harmony.

Statement 10: My life experiences have prepared me enough to manage religious or spiritual diversity

The greatest danger is that everyone thinks they know enough about the other person’s religion. It is difficult to measure how much of another person’s religion you understand without belonging to the religion.

Results indicate that 46% of respondents think that life experiences have prepared them very well to work with religiously/spiritually diverse individuals. 30% of respondents feel that life experiences have prepared them extremely well, 24% think they have adequate preparation, and no one (0%) has insufficient preparation.

Statement 11: I am well prepared to manage people who are racially diverse

Race unlike religion does not overlap in that you are either black, coloured or white. That becomes the first layer differentiating you from the other person who is not. As indicated earlier, in the South African context, race equals culture. Of particular interest is the similarity in the figures between readiness to manage religious and cultural diversity. Table 8 illustrates the responses to the statement.

According to this study 46% of managers have been prepared very well by life experiences to work with racially/ethnically diverse individuals. 2% of managers have not had life experiences for this, 28% think they are extremely prepared whereas 24% claim they are adequately prepared.

Statement 12: I am well prepared to manage elderly people with respect

Another area of contention where it can be clearly stated that what constitutes respect in one culture may not be in another culture. In the black culture it is disrespectful to call an elderly person by their first name; it will always be better to use a title and their surname as a sign of respect. Depending on the age, titles like uncle or auntie, father or mother, would be most ideal. Whilst it may be easy to use then within a racial group, very rarely would a white manager ‘call me’ a black, father or uncle. Figure 2 depicts what the managers said.

Extremely prepared (30%), 36% very well prepared with 32% adequately prepared gives a 98% preparedness. The question is what preparation and in what respect, and will these elderly feel acknowledged and respected as they would in their culture? In the absence of a standard of what constitutes working well with the elderly, it may be difficult to make a conclusion especially where racial varieties are involved.

Statement 13: Management can pull together people of diverse backgrounds

Management has the responsibility to create the enabling environment for people to work. A diverse workplace is what we will always live with, and we need to find ways of staying together and working together.

According to the results, 74% of the respondents agree, that it is the management’s role to pull the diverse groupings together and make them work towards achieving organisational goals. 20% are neutral and 6% disagree. It can be generalised here that managers accept that managing diversity is their responsibility.

Statement 14: A culture of cooperation exists amongst employees

This statement sought to identify what the managers’ perception is about their diverse employees. What does a manager do if there is no spirit of cooperation amongst the employees? Do the managers ignore and wait for the workers to sort themselves out? Or does he/she work to bring about harmony before it implodes. The managers’ perception about cooperation amongst the employees show that 70% of the managers agreed though the expectation was over 50% would have strongly agreed instead of 22%. However, this result allows a generalisation that the managers consider cooperation important in this diverse work environment. It will always be difficult to understand why some managers are neutral (18%) on issues that relate to their day to day activities. It can be that traditional management practices are used where if you cannot follow instructions then you leave the organisation. In such setups there is no need for cooperation; the manager’s voice is final.

Statement 15: There is a culture of cooperation between management and workers

Cooperation between managers and employees is of critical importance especially where innovation has to take place. Halim et al. (2015: 85) postulate that 72% of innovation in an organisation starts with the workers at operational levels. The Cape Metropolis managers’ thoughts about this are shown in Table 9.

Another surprise, the researcher expected a large percentage strongly agreeing, only 24% strongly agreed, 42% agreed (total of 66%) with 24% neutral and 10% disagreeing. Good cooperation between managers and workers allows for easy flow of information, a reduction in conflicts, and a motivated workforce leading to hire productivity. The managers responding in this survey do not think of cooperation as critical.

Statement 16: Leadership should adjust to suite the environment

The amount and nature of the power of the manager may impact on how the manager will lead. In organisations with large workforce and strong unions the leadership is more conciliatory that would be some small workforces where the shop stewards can be victimised easily. The opinion of the managers about situational leadership is as follows: 58% of the managers (34% agree and 24% strongly agree) with an abnormally high neutral at 34%, disagree combined is at 8%. Jowah (2013: 708-719) posits that followership has an influence on the way leaders lead. The followership continuum suggests that the more the power the followers have the more they can determine a preferred leadership prototype. The concern is that a very small percentage of blacks have technical skills, reducing the impact they can have if they left the organisations. It may be the correct thing to do for management to adopt leadership systems relevant to the follower if that is what will improve productivity. Unfortunately, the large part of the labour force appears to have little power and hence reduced influenced.

Statement 17: Affirmative Action (AA) has been implemented

To redress the unfairness of the past, the current government came up with affirmative action. Evidently it has not been effective; the percentage of white managers responding in this survey is disproportionately higher than the demographic ratio of the city.

Results show that a total of 58% (36% agree and 22% strongly agree) believe that AA has been implemented. A high of 28% are neutral, while 12% disagree and only 2% strongly disagree that AA has been implemented in the organisations. The great concern is whether the mere presence of a black is an indication of effective implementation or whether the ratio of the populations is used to determine successful implementation.

Statement 18: Cultural diversity is viewed as racism

The white opposition (political parties) has constantly asked for a sunset close to the AA program. Consistently they refer to this as reverse racism, and since these opposition parties have a white constituency, in general white managers may be opposed to Affirmation Action. This may explain some of the preceding results.

This statement was not responded to decisively as seen by the low scores: 32% strongly disagreeing with 16% disagreeing (total of 48%) allowing for no generalisation. Those agreeing were total 28% which is about the same number of white managers responding (10 strongly agreeing and 18 agreeing) and exactly the percentage of black managers involved.

Statement 19: Cultural differences present obstacles in communication

This is one element of human behaviour and interaction which may cause unnecessary misunderstandings. Apart from language problems where the larger part of the population uses English, the percentage of people whose mother tongue is English in South Africa is estimated at 6%. There is cultural symbolism in communication that may introduce another dilemma in communication. The managers’ response to this statement is as follows: 52% agree (14% strongly agreed and 38% agreed) that cultural differences cause difficulties in communication. Just over one quarter (26%) of the respondents remain neutral leaving a total of 22% to disagree. It needs to be emphasised here that communication causes problems even among people of the same culture. The major cause of communication amongst people of different cultures may have more to do with inadequate knowledge about the other culture, stereotyping of cultural groups or simply arrogance stemming from ethno-centricism.

Statement 20: Cultural differences present obstacles in work performance

If cultural differences cause communication problems, then they are enough to cause or affect performance. Failure to communicate effectively amongst the employees keeps people in their racial groups and makes them permanently reside in silos. This will create “a them and us” which may not allow for effective cooperation amongst the workers. As usual surprises come from the managers, as recorded in Table 10.

Again the neutral managers’ score is at 42% leaving a small portion of 20% total to disagree and a total of 38% to agree. This may be a clear indication of the absence of correct relevant competencies to manage effectively culturally diverse teams. The managers have no ability to separate culturally related problems from the traditional problems; this may also be a clear indication that the managers need more training in this aspect of their work.

Statement 21: Communication is a critical success factor in the organisation

This time the statement makes reference to communication in general and the managers responded overwhelmingly. The responses are as follows: 92% unusual managers accepted that communication was critical for effective organisational function. It then raises questions as to whether the managers will accept that cultural differences may create differences that might affect effective communication. Because this statement did not make reference to cultural diversity, the neutral dropped to an all-time low of 2%. Again this may create room for the researcher to hypothesize that, for whatever reason, managers were reluctant to respond to questions relating to cultural diversity.