ABSTRACT

This article aims to investigate the complex interrelationship existing between reporting, accountability and governance of municipalities. More in detail, the paper attempts to identify the internal and external conditions inducing municipalities to keep environmental reports (Research Question 1) and to assess the impact of environmental reporting on the accountability of the municipalities’ governance (Research Question 2). Multiple Case Study Research is conducted by administering semi-structured interviews to bureaucrats belonging to Accounting or Environmental Department of twelve municipality partners originally involved in CLEAR-Life project. The analysis shows the link between environmental reporting, governance and accountability, fostering the identification of some important factors which may induce municipalities to elaborate environmental reporting, the impact of which should improve accountability. The work highlights possible governance settings that should stimulate scholars and practitioners to acquire a more mature awareness about the importance of adopting sustainable practices for the implementation of budgetary policies. The paper summarizes the enabling conditions to leverage governance mechanisms, which may lead political representatives to pursue an environmental accounting-oriented culture and, therefore, environmental awareness and responsibility.

Key words: Environmental reporting (ER), accountability, governance, local government (LG), municipality, multiple case study, semi-structured interview, CLEAR-Life.

Western economies have been successful in creating a higher level of consumption (perhaps even well-being) but it is not in question that the planetary environment is declining seriously and rapidly (Dragomir and Anghel-Ilcu, 2011; Gray and Bebbington, 2000). To face this global challenge, the UN World Commission on Environment and Development published the Brundtland Report (WCED, 1987), a relevant step where the concepts “sustainability” and “development” are used together. It is considered the guiding principle linking environmental and human development concerns (Bebbington and Larringa, 2014; Bebbington et al., 2014).

In 1992, with the Rio’s Earth Summit, the principle of sustainable development was fully approved. The international context has played a fundamental role in shaping European environmental policies, based on co-operation of many political actors: EU institutions, national authorities and interest groups; all with widely differing agendas (Delreux and Happaerts, 2016). In this regard, the international trends for greater accountability and environmental responsiveness from the public sector, with particular regard to the governance of public administrations at local level (Johanson, 2014), further encourage the establishment of new research on the promotion and implementation of sustainable development practices (Crosby and Robbins, 2013). Moreover, Chapter 28 of Agenda 21 declares that many problems linked to sustainability can be solved only at a local level (Meakin, 1992). Thus, the governance of Local Governments (LGs) seems to play a pivotal role in fostering their accountability (Hyndman and McKillop, 2018; Niemann and Hoppe, 2018; Larcker et al., 2007; Marcuccio and Steccolini, 2005), especially with regard to the environmental theme and, more in general, to the sustainable development, having the capacity to relate directly to society, outline the trajectories of development, define and implement policies, make choices, identify and solve community problems (Dragomir and Anghel-Ilcu, 2011; Papaspyropoulos et al., 2010; Ball and Grubic, 2007). This consideration acquires value by virtue of the fact that in many industrialized countries the governance models of the LGs, especially in the environmental sphere, show numerous limitations (Hyndman and McKillop, 2018) with respect to identifying possible solutions to emerging problems and new diversified needs, coming from actors in economic, institutional and civil society contexts.

The environmental crisis tangling the planet in a vicious circle of pollution generates uncertainty toward the future prospects for the governance of many LGs (Ntim et al., 2017), highlighting the need to trace new ways of managing accountability systems and, more generally, defining and implementing environmental policies. In light of this increasing need, the systems for adopting environmental policies are progressively evolving (Li and Song, 2018; Chapple et al., 2018; Richards et al., 2016; Jan van Helden and Vakkuri, 2008), moving from government structures, characterized by rigidity and vertical integration, to governance models, characterized by the promotion of initiatives based on the principle of shared accountability, on effective collaboration between public and private actors at different levels, on alignment of goals, on the synergic integration of resources and on the co-creation of value between local authority and citizen (Baker and Schaltegger, 2015). In this regard, Local Agenda 21 (LA21) summarizes the necessary actions to be taken, the stakeholders to be involved and the tools to be used to orient the governance of LGs toward a full environmental accountability according to a logic focused on the global sustainable development. One of the measures included in Agenda 21 was meant to integrate sustainable development in governance, policy making, plans and strategies. Coherently, LGs have begun to embrace the new tools of Environmental Accounting (EA) as necessary steps toward understanding and managing change (Ball, 2005).

EA can be identified by the organization effort to legitimate activities; an ethically desirable component of any well-functioning democracy; and one of the few available mechanisms to address sustainability (Gray et al., 2014). By adopting the environmental policies classification of what Giovanelli et al. (2005) defined as “third generation”, EA is concerned with the production of ‘accounts’ concerning organizations’ interaction with the natural environment considered as an integral part of all the available resources. As stated by Bebbington and Larrinaga (2014) there is no clear demarcation in literature between EA and sustainable development. Specifically, EA is seen as an essential mechanism, together with sustainability science, in mapping the future direction of organization towards sustainable development. Hence, EA can be considered as a key step to provide insights that will help the advancement of sustainable development. Thus, it may be considered as a response to internal and external users’ needs about the ambiguity and complexity of sustainable development measurement. Similarily, EA could be an answer to some of the weaknesses of accounting and related conceptual frames (Unerman and Chapman, 2014). The Environmental Reporting (ER) is the main EA document, through which the LGs governance shows the territorial commitment to the various local stakeholders (Braam et al., 2016), specifying in detail - that is, through both monetary and physical indicators, the effects produced by the policies adopted and the possible effects deriving from future actions not undertaken yet. By drafting and approving the ER, LG, in addition to describing and making public the environmental policies and the related economic-financial aspects, analyzes and documents, through data and statistics, the direct and indirect impacts on the environment of the decisions taken (Buhr, 2002). ER is the process of communicating the environmental effects of organizations’ economic actions to stakeholder (Gray et al., 1987). As such, it involves numbers of purposes but discharge of the organization’s accountability to its stakeholder must be the dominant of these reasons.

Although there is a considerable international interest in the subject of environmental protection, to date, the number of studies aimed at investigating the link between governance, accountability and ER of LGs is still exiguous (Grubnic et al., 2015). In addition, prior research shows that, also in terms of operational practice, environmental accountability seems not to be a synergistically and completely integrated governance processes, activities and actions of LGs even today, if not with reference to the environmental legislation to be respected (Farneti, 2011). Moreover, academic investigation is needed to help understand where specific environmental-related accounting initiatives lie on the continuum between pure rhetoric and meaningful action. Furthermore, it informs the most aware and effective use of the accounting for sustainable development in a broad range of organizations.

Therefore, considering the high relevance of the topic, the goal of this article is to analyze the results coming from an investigation of complex interrelationship existing between reporting, accountability and governance of municipalities. More in detail, the paper aims to provide an empirical evidence of the factors improving accountability, governance and their relationship with environmental reporting of municipalities. To this end, the work attempts to provide an answer to the following two Research Questions (RQs):

RQ1: Which factors induce the LG to introduce the ER?

RQ2: How does ER impact on the accountability of the municipalities’ governance?

LGS BETWEEN GOVERNANCE, ENVIRONMENTAL ACCOUNTABILITY AND REPORTING

From governance to environmental accountability

The importance attributed to the environmental accountability finds a more immediate justification in the public sector. The traditional role played by public bodies at every level fits perfectly with the objective of shielding citizens’ health, through the definition and implementation of specific policies of government. These policies promote environmental protection and minimize the impact generated or that may be generated by human actions (Ball et al., 2014).

The strong link that exists between the environmental accountability and the governance of public administrations, although debated for many years, acquires meaningful significance in the early 1990s (Jepson, 2005). Since that moment, there has been a growing interest in articulating a powerful normative regime characterized by practices and policies, aimed at attributing responsibility to any social actor in terms of environmental awareness (Brown and Moore, 2001).

Over time, the increasing attention that LGs have been given to the environment and its protection has produced a real change of perspective in the formulation of government policies (Bartelmus and Seifert, 2018). It progressively became more and more focused on the diffusion of a sense of morality, legality and, more in general, accountability in the civil society (Lodhia and Stone, 2017). As a result, scholars and policy makers started to wonder about the efficacy of policies adopted for and within the public sector, taking the link between politics, governance, morality, and accountability to the top of the agenda in the environmental sector (Jepson, 2005).

Governance models in the public sector have begun to embrace an accountability-oriented approach (Delreux and Happaerts, 2016), based on an integral and responsible management of public bodies. The key elements are legality and possibly the principle of rationality (Armstrong, 2005). Governance policies, while continuing to recall the legality of actions and the rationality of behavior, necessary for making decisions compatible with the available resources and the set objectives, focus the attention on the moral meaning of accountability, inspired by responsible human conduct and values toward the exclusive interest of the community (Larcker et al., 2007). In this sense, the set of values characterizing the policy makers’ choices constitute ethics. It is defined, according to a moral perspective, as a spiritual presupposition of human conduct, in compliance with the rules defined in the broad and strict context of legality (Edwards, 2007). Therefore, the affirmation of accountability in the governance policies of public bodies emerges as a link between the rational interest of those who guide the public body in respect of legality, and the interest of the social community in which it is placed and acts (Laratta, 2011). The deepening of the link between governance and environmental accountability has favored the development and the continuous updating of techniques and practices that delimit the theoretical and normative framework. In this context, the LGs adopt concrete actions for the administration of territory and environment (Lehman and Morton, 2017).

To date, except for some unusual exceptions, all LGs place emphasis on the definition of a connection between territorial governance and environmental accountability (Armstrong et al., 2012). This link is aimed at implementing procedures and tools capable of favoring the improvement of the level of effectiveness and efficiency of the decision-making process (Bakre, 2011). Moreover, the greater the depth of the aforementioned relationship, the more intense is the involvement and the engagement of all the community actors - not only citizens - in the decision-making process of the LG (Grubnic et al., 2015).

The governance of a LG summarizes the set of methods by which policy makers organize and guide political action as a whole in a specific context of the territory (Aiqin, 2006). The reference is not only to the quantity but also the quality of the interventions, measured in terms of effectiveness, efficiency, timeliness and consistency with respect to the needs of the community.

In the last decade, the models of territorial governance for the accountability of LGs have evolved in line with the changing political, economic, social and environmental conditions (Larcker et al., 2007). This process has marked the passage from a hierarchical structure to a strategic vision of territory management in the medium and long term, focused on the horizontal and vertical integration of functions (Li and Song, 2018).

The crisis of hierarchical governance models for environmental management was determined by the acquisition of a more mature awareness on the inadequacy of "one-way" policies for the regulation of the system relations. These links are characterized by a growing complexity of social phenomena, as well as political and economic issues that affect the territory (Ntim et al., 2017).

Over the years, LGs understood the need to recognize as a priority the citizens’ participation and empowerment towards the definition and implementation of environmental policies (Richards et al., 2016). In other words, having defined the relevance and legitimacy of procedures and methods to elaborate political-environmental decisions, in this sense Foucault (1991) talks about "governmentality", the participatory paradigm must concretely be inspired by the principles of openness, participation, accountability, effectiveness and consistency.

In this sense, the link between governance and environmental accountability is expressed in the set of coordination mechanisms of the territorial actors. They are aimed at sharing sustainable development to promote the elaboration and implementation of coherent territorial initiatives (Crosby and Robbins, 2013). In this sense, LGs need to adopt environmental policies able to guide, train and involve all public and private organizations, civil society and individual citizens in the territory, both in the planning and in the implementation phase (Bebbington and Unerman, 2018), overcoming the limits imposed by the concentration of power in the hands of a single subject. As a result, public and private actors involved in the sustainable development debate could have been more aware of proposals for sustainability policies and practices.

From environmental accountability to environmental reporting

Among the tools used by LGs to strengthen their accountability, with respect to the needs of the territory and the expectations of the community, ER plays a leading role in the process of defining governance policies (Debnath, 2019).

In the context of accountability processes, ER allows and facilitates the detection, organization, management and communication of environmental information by means of indices expressed in both physical and monetary units (Bennett and James, 2017).

In the public sector, ER was born as a response to the desire of institutions to develop a broad system of accountability (Baker and Schaltegger, 2015). It consists of a set of reporting procedures, equipped with not only economic or financial nature but also environmental dimension (Margerison et al., 2019). These processes can quantify the overall impact of policies, actions, interventions and, more generally, activities with repercussions on the territory (Deegan, 2017).

ER proves to be capable of obviating the inadequacy of traditional accounting instruments - mostly of an economic, equity and financial nature - in satisfying the needs of accountability (Margerison et al., 2019; Menicucci and Paolucci, 2018). Moreover, it identifies environmental problems (Schaltegger and Burritt, 2017), and proposes solutions capable of stimulating the overall well-being of the local community (Sendroiu and Roman, 2007), pursuing the collective interest (Stanciu et al., 2011) and better goals on environmental quality, life and sustainability of development (Evangelinos et al., 2015).

By adding an EA system to traditional financial statements, LGs are able to meet the information needs to show and “demonstrate” their accountability (Georgakopoulos, 2018). This system allows to appropriately account for environmental costs and benefits coming from current or future actions, also increasing transparency toward the outside and implementing effective and efficient policies (He et al., 2019). Therefore, ER satisfies a dual communication requirement: internal, as a supporting transversal and strategic document in the decision-making process of the entity (Garcia-Torea et al., 2019), and external, as a tool of transparency and democracy to account for all the stakeholders of the territory about environmental policies (Vassillo et al., 2019).

Although it is part of a set of principles shared at an international level for a long time and that many strategic documents support its adoption, ER is a voluntary tool (Lehman and Kuruppu, 2017; Steele and Powell, 2002). Sustainability within the urban context has been widely debated, however, there is still a general lack of integrated solutions and coordinated actions, which are required for addressing such a complex issue (Muserra, 2020; Buhr et al., 2014; Farneti and Siboni, 2011; Mazzara et al., 2010).

Within the sustainability framework, much of the current literature on ER (Greiling et al., 2015; Buhr et al., 2014; Lodhia et al., 2012) focuses on the adoption of the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI).

The GRI has been a widely adopted framework for ER to disclose economic, environmental and social performance in a comparable way and creating a transparent and reliable network of sustainability information (GRI, 2002).

However, GRI’s guidelines, that are widely used by companies, have failed to grasp public sector sustainability approach, being too managerial. Indeed, they are based on the assumption that there are no oppositions between the traditional economic criteria and those related to social and environmental aspects.

Therefore, they seem unaware of the notions of ecology and eco-justice - focusing on establishing whether or not organizations act as sustainable members of society (Dumay et al., 2010).

In this context, there is a lack of environmental sustainability in the public sector (Goswami and Lodhia, 2014) and often reports show considerable diversity not recurring to any guidelines (Williams et al., 2011).

In the last decades, despite the voluntary nature and the lack of effective official guidelines, a growing number of LGs has experimented the ER (Williams et al., 2011; Marcuccio and Steccolini, 2005). This situation may lead to unconsistency and uncomparability, which would be avoided in case of a known standard (Lodhia et al., 2012). Moreover, it may raise some concerns about the effectiveness of ER as a tool able to enhance transparency and accountability. For LGs social and environmental responsibility cannot be a mere ethical option. It should also be taken into account that the relationships with stakeholders are here very complex and layered, namely the relationship with citizens/voters/taxpayers who are often also customers (Ricci, 2016). Generally, it seems that ER refers to citizens; however, some authors argued that the favoured audience is often that of internal stakeholders (Farneti and Guthrie, 2009).

In light of what has been described so far, the ER takes shape as a useful tool for reporting and publicizing the accountability of LGs (Cormier and Magnan, 2003): through the use of this instrument, the institution becomes socially responsible for the protection of the environment, due to the policies adopted and the choices made in implementing the commitments and objectives previously set.

The choice of LGs to draw up an ER comes from the increasingly pressing request for transparency on policies and strategies oriented towards sustainability (Debnath, 2019). Within the concept of sustainability in its triple meaning, the conflation with the environmental aspect plays a fundamental role (Bennett and James, 2017). Indeed, it stimulates the administration towards a community approach. Compared to other documents referable to the sustainability reporting framework, an adequate ER drafting and publication process is able to increase the transparency of LG's action. Thus, it would provide a representation of environmental policies. Namely, it allows policy makers to monitor the results obtained following the integration of targeted environmental policies, redirecting the decision-making process of the LG towards greater transparency, stimulating a more considerable stakeholder involvement, and facilitating the implementation of environmental management systems (Gray et al., 2014). The growing attention that public opinion, LGs and, more generally, all stakeholders pay to environmental issues is prompting administrations to tune the communication tools of sustainability (Delreux and Happaerts, 2016). By examining the various threads that make up ER, it is possible to contribute to the advent of sustainability as a meaningful concept (Buhr et al., 2014). Through the publication of the ER, environmental sustainability is assessed in terms of both efficiency and effectiveness, with regard, for example, to monitoring the energy consumption, verifying the waste management, and controlling the water use and purification. Therefore, the ER satisfies a fundamental need for the sustainable management of LGs: the complete, exhaustive, correct and transparent representation of the administration-environment relationship (Margerison et al., 2019). For LGs the ER represents not only a mere reporting document but also a political-institutional tool (Garcia-Torea et al., 2019). It can benefit from the construction of a base of indicators concerning the environment to identify problems (Wheeler and Elkington, 2001) and define corrective interventions (Marcuccio and Steccolini, 2005). Moreover, it can bring the environment to the center of the political debate (Lodhia et al., 2012) and, consequently, guide future development trajectories to build a path of development devoted to sustainability in its triple form: economic, social and environmental.

In order to reach the research aims (Woodside and Wilson, 2003), seeking to probe theory description directly applicable to practical problems, reaching both an academic and professional audience, a case study research (Eisenhardt, 1989; Starkey and Maden, 2001; Visconti, 2010) was implemented. The main benefit coming from its use is not to generalize findings to a population (Yin, 1994), but the opportunity to deepen the knowledge (Skinner, 1963), adopt a system thinking (Gummesson, 2003) and provide a phenomenological approach that focuses on the lived experience of individuals as the main empirical evidence (Thompson et al., 1994).

For this work, rather than a Single Case Study, it was decided to adopt a Multiple Case Study (MCS) approach since the latter allows for the analysis of complex phenomena and situations (Lamboglia et al., 2018), like the link between ER, accountability and governance of municipalities.

Furthermore, MCS offered the opportunity to determine possible differences and similarities among the several cases under analysis (Lambert and Sponem, 2012). Therefore, the risk of making considerations based on results affected by uncontrollable factors (e.g. casualty, coincidences, etc.) is reduced, and scientific rigor by ensuring higher reliability to the discussion (Corcoran et al., 2004) is guaranteed. In the accounting literature, many other authors employed that research method, and it is possible to trace several scientific contributions that recommend its use (Becker, 2014; Del Bene and Ceccarelli, 2016).

Although each author sticks up for her/his own idea about how MCS should be defined, such as the research objectives, analysis context, historical period, etc., for this work the application of MCS implied the need to treat separately each case taken into account, that is, as an individual case, in order to ensure the reliability of research, the replication of analysis and the comparability of findings (Del Baldo and Aureli, 2017). Theories, ideas, hypotheses, assumptions, statements, propositions, principles and postulates deriving from the study of other cases represented the reference framework for this research as a whole: the MCS allowed authors to investigate more deeply the factors inducing the LG to introduce the ER (RQ1) and to understand the ER impact on the accountability of the municipalities’ governance (RQ2).

Finally, investigating the link between ER, accountability and governance by means of the separate analysis of all individual sub-units, the municipalities, was necessary to maintain for each of them the same set of basic assumptions, although the progress of the analysis could lead to further considerations, enriching the theoretical and experiential baggage.

Data preprocessing

The first activity carried out to choose the actors of analysis was aimed at selecting a method used by more than one municipality to draft their ER. In this regard, the attention was paid to CLEAR-Life - Acronym of "City and Local Environmental Accounting and Reporting"- since it was a case-relevant opportunity financed by the EU and led by LGs network participation (CLEAR, 2003).

Indeed, the absence of technical information prompted the European Commission to boost, in 2001, this new method to elaborate ER, which copes with transparency, citizens’ awareness and LGs commitment with respect to the policies adopted (Borriello, 2013).

This was set within an inter-institutional working group assisted by public and private key stakeholders to deliver guidelines in ER (collected into a proper manual). It was used for about 16 years (Di Palma et al., 2005) and it appears to be a predominant method for frequency of application in Italy which has introduced a complete and structured methodology (Bartocci and Picciaia, 2013) that involves both technical and political actors, such as the Executive Committee, the Council and even the Mayor.

Most of the CLEAR-Life partners mainly belong to the Emilia-Romagna Region. This accuracy allowed to reach a homogeneity, not only in terms of time perimeter (according to its financial incentives, 2001-2003, and its period of adoption by 2004), but also confining the sample according to space perimeter. In particular, it was introduced thanks to the commitment of a working group made by 18 Partners (municipal and provincial administrations), coordinated by the joint action of the Emilia-Romagna region and the international association Les Eco Maires - which includes about 600 municipalities adopting sustainable policies, as part of a European project co-funded by Life Environment (Dalmazzone and La Notte, 2009).

Information was gathered about the publication of ER by CLEAR-Life municipality partners (12 out of 18), without including provinces. All the twelve LGs CLEAR-Life partners were contacted to ascertain whether they had adopted ER and, if so, to analyze their ER practices by means of interviews with the people involved in the report preparation process and documentary analysis.

Data collection and analysis

In order to achieve the predetermined research objective and, therefore, to provide empirical evidence of the accountability and governance role within the elaboration of ER in a LG context, it was decided to take care of both fulfilling and defaulting LGs.

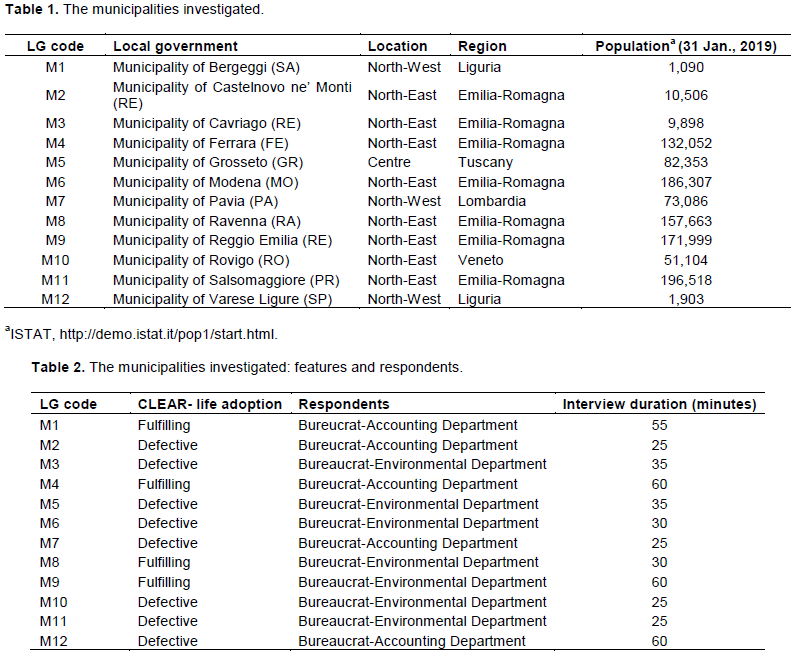

Table 1 shows some significant data relating to the LGs - reported in alphabetical order - belonging to the sample under investigation.

As shown in Table 2, the aforementioned procedure returned 4 LGs, out of the 12 partners, that today continue to elaborate ER. In order to achieve the predetermined research objective and, therefore, to provide empirical evidence of the reasons that lead to elaborate the ER, it was decided to contact the whole sample of LGs to achieve a multifaceted vision of the phenomena. Each interview varies according to the availability and the actual feasibility of the analysis. For this reason, the interviews administered to the bureaucrat of the accounting or environmental offices of municipalities indicated earlier lasted differently from a minimum of 25 min to a maximum of about 60 min.

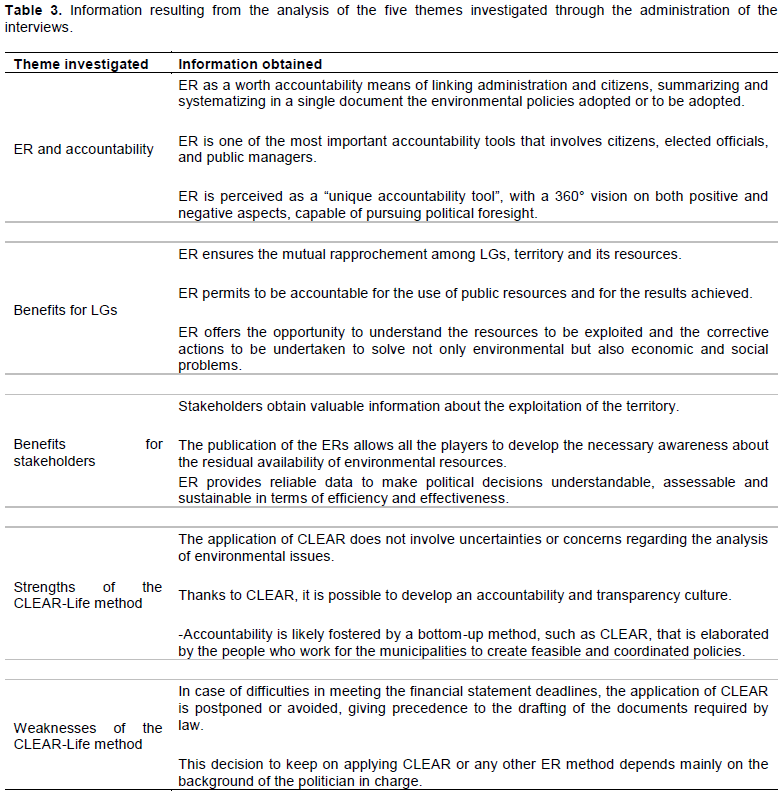

The interviews were designed by following the four-step interactive guide of designing and conducting interviews, proposed by Arsel (2017). In particular, the analysis was performed by administering semi-structured interviews, designed by taking into account the motives characterizing the choice of continuity made by the four municipalities which, after a long time, are continuing (M1, M4, M8, M9) or have stopped (M2, M3, M5, M6, M7, M10, M11, M12) drawing up the ER. The use of semi-structured interviews, rather than open, is justified by the consideration that, although there is a fixed trace, the development of the interview may vary according to the interviewees’ answers (Horton et al., 2004). In fact, administering semi-structured interviews, the interviewer cannot address off-track issues. Moreover, unlike structured interviews, he/she can develop some sub-topics that spontaneously arise and that could be useful for understanding the investigated phenomenon. The interviews were designed by identifying five themes: (a) ER and accountability; (b) benefits for the LG; (c) benefits for stakeholders; (d) strengths of the CLEAR-Life method; and (e) weaknesses of the CLEAR-Life method.

The results that emerged from the survey show that all the respondents have identified the importance of the LGs’ accountability and its link with ER, corroborating the Ntim et al.’s study (2017), according to which the local institutions cannot ignore the need to trace sustainable trajectories in the adoption and implementation of their policies:

“ER emerges as a worth accountability means of linking administration and citizens, ... capable of favoring their mutual rapprochement ... as well as the enhancement of territory ... and its resources, not only under an environmental profile" [Quoted from M9];

“the ER, while not guaranteeing the identification of consistently feasible solutions, implies the need to constructively discuss environmental issues, preventing the less positive aspects from being covered up" [Quoted from M6].

In compliance with Hyndman and McKillop’s point of view (2018), LGs play a leading role in promoting the sustainable development of society and in stimulating the spread of accountability:

The stakeholders with which LGs come into contact can benefit from obtaining valuable information about the exploitation of the territory. In fact, the publication of the ERs allows all the players belonging to the social context in which LG takes part to develop the necessary awareness about the residual availability of environmental resources [M6 and M9].

However, the decision to or not to elaborate the ER depends on different governance settings defined by conditions that are not always controllable:

“while acknowledging the ER as the main tool for disseminating the culture of accountability and the transparency of environmental policies adopted by LGs, it is neither obvious nor easy to provide for its drafting" [Quoted from M5].

Despite the consciousness about the role of the ER in accountability, some of them claimed that without an economic support and the scarcity of human resources, it is difficult to elaborate the ER:

“ER is one of the most important accountability tools that involves citizens and elected officials on one side, elected officials and public managers on the other… it permits to be accountable for the use of public resources and for the results achieved… however the staff is scarce… we have many emergencies and few economic resources…

allocating a person specifically to work on the elaboration of ER is not always sustainable” [Quoted from M2];

“…all these fulfilling LGs have the possibility to rely on rooted personnel that convey the same spirit of the initial phases” [Quoted from M8].

This was confirmed by the interviews carried out to defective municipalities:

“when the project was activated I was not here and I have not been informed about ER…” [Quoted from M11].

“The person in charge when the project was activated is now retired” [Quoted from M7]. “Even if I were there, I have never managed ER” [Quoted from M12].

Coherently, just less than the two million euros, which covered 50% of the start-up and development costs through funds allocated to implement the Life-Environment program:

"To initiate the ER elaboration, the co-financing received from the European Commission was the most concrete driver" [Quoted from M9].

Besides the interruption of the financial incentives and problems connected to human resources, the absence of a binding regulation regarding ER for municipalities also emerged as a motive of defection. In fact, as Lehman and Kuruppu (2017) point out, although in the last decade a growing number of LGs is experimenting the ER, it keeps on being a voluntary disclosure document, often ignored while being recommended and shared internationally.

Even if “CLEAR-ER application does not involve uncertainties or concerns regarding the analysis of environmental issues” [Quoted from M8],

“its application was not compulsory…if you could not meet the financial statement deadlines you had to focus attention on that… so the decision was made to remove non-regulatory instruments including ER. Furthermore, in case of difficulties in meeting the financial statement deadlines, the application of CLEAR is postponed or avoided, giving precedence to the drafting of the documents required by law” [Quoted from M10];

“Nowadays municipalities cope with mandatory budget instruments… the guideline on the ER was just recommendation even if significant, we preferred to engage on what is required to avoid any problems” [Quoted from M3].

This decision to keep on applying CLEAR or any other ER method depends mainly on the background of the politician in charge:

“Not everyone is capable of managing sustainability issued. Thanks to CLEAR, it is possible to develop an accountability and transparency culture” [Quoted from M1].

However, the ER can be seen as the viaticum for the continuity of the administrative action:

"year after year, through final report and preventive programmatic lines, the governance process is enriched with elements compatible with the ultimate aim of catalyzing the policies, strategies and actions of the LG towards a concept of wide-ranging and three-dimensional sustainability, … including aspects related to environment, economy and society. The drafting of the ER, in the sense of satellite report of the financial statements, pursues the political foresight of LGs” [Quoted from M9].

Although over the years the guiding principles of ER have been characterized by a growing level of effectiveness and efficiency, according to M5:

"... the drafting of the ER requires, in any case, a long time span - for reporting, identification of problems, the proposal of solutions in the preventive report for the following year, the adoption of improvements or corrective actions, the evaluation of the results generated by the actions carried out, and so forth - which are all incompatible with the 5-year term of legislature".

Besides the incompatibility with the legislature time-span, another decisive deterrent to the adoption of the ER seems to be, as M5 adds:

"... the lack of a direct connection with the civil budget, ... which prevents the creation of a useful connection with the final data and with the future planning of the local authority, ... inhibiting the thematic coverage of all the skills and areas of activity" [Quoted from M5].

The report-oriented culture was pursued by four LGs (M1, M4, M8, M9), where ER is perceived as a “unique accountability tool”, with a 360° vision on both positive and negative aspects, capable of pursuing political foresight. In this perspective:

“..ER provides a historical series of data with the objective to investigate environmental issues related to positive aspects and negative circumstances… This document provides significant information to council members by offering the opportunity to understand the resources to be exploited and the corrective actions to be undertaken to solve not only environmental but also economic and social problems” [Quoted from M1].

“...ER summarizes and systematizes the environmental policies adopted or to be adopted in a single document... CLEAR methodology has developed accounting and reporting standards that support environmental, societal and economic policies to increase the citizens’ satisfaction” [Quoted from M4].

“ER information significantly affect technical and political job actions by providing reliable data to make political decisions understandable, assessable and sustainable in terms of efficiency and effectiveness” [Quoted from M8].

In this sense, ER constitutes a document for LGs, which are required to adapt to the continuous change of society (Ball, 2005) to address sustainability (Gray et al., 2014). Likewise, several authors (Margerison et al., 2019; Bennett and James, 2017; Baker and Schaltegger, 2015) underline the importance of the work performed by the ER in enabling the identification, organization, management and communication of information on the environment through specific physical and monetary indices.

“The ER offers a 360° vision, … allowing to overcome the limits of other very common reporting tools, such as, for example, the social balance sheet, drawn up occasionally, without a uniform approach and, above all, traditionally characterized by the attempt to emphasize only the positive aspects, leaving shortages and problems of various kinds” [Quoted from M9].

In this regard, ER takes shape as a solution (Menicucci and Paolucci, 2018) capable of promoting sustainability (Evangelinos et al., 2015) and promoting the well-being of the local community (Sendroiu and Roman, 2007).

Moreover, the M8 experience explains that the ER has contributed also indirectly by increasing the municipal engagement in the environment:

“the information elaborated through ER was useful to exploit other European Project opportunities... it was decided to participate in EMAS which allows a codified external evaluation tool... even if it does not refer to the entire process of sustainability as the ER does”.

Indeed, EMAS is an environmental management system based on the “Plan-Do-Check-Act” process (Giovanelli et al., 2005) and, as stated by M8:

“it does not provide the analytical information required to obtain a full internal and external accountability situation... so EMAS is not an integrated tool and it cannot replace the ER... however, the EMAS verification and registration processes have highlighted the need to modify and integrate the ER structure that was initially adopted with the CLEAR-Life project”.

Thus, this statement also highlights the importance of possible external network connections, confirmed by M9:

“Once the ER process was supported by topic related meetings developed by the LA21 that are not held anymore…which also entailed a strategic plan for sustainable development in the XXI century through participation discussing all the environmental issues...”.

Moreover, this case study was the only one to achieve a benefit in terms of European projects, indeed:

“with the new European projects there is a lack of practicality…the last trend is to structure projects like toolkits which is an ineffective method for municipalities” [Quoted M9].

Therefore, while adopting and implementing sustainability policies, accountability is likely fostered by a bottom-up method, such as CLEAR, that is elaborated by the people who work for the municipalities to create feasible and coordinated policies in favor of citizens. Consistently, Li and Song (2018) and Chapple et al. (2018) argue that environmental policies are progressively evolving towards governance models increasingly oriented towards the promotion of initiatives based on the principle of widespread accountability, promoting the co-creation of value between LGs and citizens.

For an easier understanding of the results, Table 3 summarizes the information resulting from the analysis of the five themes investigated through the administration of the interviews:

Work implications

In the attempt to investigate the conditions stimulating LGs to keep - or not to keep - ER and its impact on the accountability of the municipalities’ governance, the article offers its contribution under a twofold profile, theoretical and practical, providing potentially interesting and useful insights for both scholars and practitioners.

From the point of view of the theoretical implications, the work builds on existing areas of research into accounting for sustainability and suggests some broad avanues for sustainability-related accounting research. Specifically, it contributes to the literature enrichment about the connections to be created between governance, ER and accountability. Through an analysis of the possible drivers of governance settings, it stimulates a more mature awareness about the relevance of adopting sustainable practices for the implementation of budgetary policies (Niemann and Hoppe, 2018; Marcuccio and Steccolini 2005). In line with the most recent contributions on ER (Margerison et al., 2019; Vassillo et al., 2019), LGs need to pay attention to the concept of sustainability (Lehman and Kuruppu, 2017). The study explores the main governance factors pointing out that elected officials and public managers are responsible for the use of public resources and for the results achieved. Drawing up the ER is configured as a very useful tool (Muserra et al., 2020): it defines to whom the department is accountable and what for, providing valuable information. ER structure is not limited to the gathering of merely numerical data (physical and/or monetary), but it also provides findings produced by environmental policies implemented (final data) or to be implemented (prospective data) by LGs. For example, they are linked to the amount of waste produced, water consumed, green spaces preserved, pollution caused, and energy generated.

The information derived from the analysis show some important factors that stimulate LGs to introduce ER (RQ1) and define how ER impacts on the accountability of the municipalities’ governance (RQ2).

Addressing the RQ1, pivotal factors are represented by practical reporting process; bottom-up approach, need for a regulatory policy, and the background of the politician in charge.

In this scenario, the work offers the relationship between ER, governance and accountability, identifying some of the most relevant factors, which may represent the conditions that induce municipalities to elaborate ER, the impact of which should be to improve different types of accountability (e.g. political, legal and moral).

Indeed, turning the attention to RQ2, this analysis suggests that the adoption of ER can be seen as a tool for making claims, demanding a response and sanctioning non-responsiveness. Then, accountability can be seen as a means of the governance to achieve a wider set of political actions including aspects related to environment, economy and society, but also appropriateness of policy-making processes. Traditionally, exercising accountability involves elements of monitoring and oversight, whereas this paper also highlights the necessity to include the rule of reason, as well as the rule of law. Inter-institutional collaboration is meant to raise the logic of public reasoning, including not only legal, but also moral accountability.

Potential sites for theoretical innovation deal also with challenging definitions of entity boundaries, indeed, this paper discusses the drivers and intervention between municipalities and other entities. Therefore, albeit not always explicitly, it creates the space within which we might understand what entities, but also what inter-institutional relationships, are relevant for accounting on sustainable development scholarship. This paper refers to the role of LG to enhance an ER and, more broadly, non-financial disclosure-oriented culture, highlighting the necessity to act homogeneously. Indeed, the LG engagement towards sustainability practices should be the result of a concerted action. Moreover, it identifies how the accountability depends on some of the most important governance factors inducing municipalities to draw up ER. Thus, it analyzes a new conceptual framework (Unerman and Chapman, 2014) re-examining the conceptual basis of ER. With a view of accountability, these governance factors are identified as drivers of a reporting-oriented culture on the environment, which incorporates environmental issues into policy-making processes and provides accountability incentives. This is considered of high importance for researchers as well as for practitioners, considering that these latters have been quick to deeply comprehend the potential of sustainable development (Bebbington and Unerman, 2018). In this context, both bureaucrats and politicians can develop an important role for themselves as part of the intervening process. They can help translate and adapt the government-level commitments within sustainability, into organizational-level actions and achievements.

Based on the results arising from the analysis of the responses to the interviews administered, it is possible to summarize the enabling conditions to leverage governance mechanisms, which may lead political representatives to pursue an ER-oriented culture and, therefore, environmental awareness and responsibility.

As highlighted by previous researches (Farneti and Siboni, 2011; Mazzara et al., 2010), the presence of binding regulations could be an effective instrument to improve urban environmental sustainability. However, until now, it has been argued that the lack of specific content, a definitive method of reporting, and a valid enforcement system have marginally influenced the provision of non-financial information (Williams et al., 2011; Buhr et al., 2014). As already suggested by social and environmental accounting scholars (Dumay et al., 2010), this paper claims the necessity of a regulation capable to foster a more extensive and better-quality reporting in the interest of the wider society. To this end, a strong impetus could derive from the introduction of regulatory policies that oblige LGs to draw up ER, possibly creating links with financial statements. In this regard, it may be useful to have the municipal administrations draw up ER in compliance with time constraints and the process for the statutory financial statements.

In this way, it would emerge a legal accountability, monitoring the observance of legal rules and prompting all the LGs adopting sustainability-related reporting.

Moreover, other factors that could positively influence the adoption of ER are, for example, practical reporting processes, continuity of administrative actions and bureaucratic stability. On the other hand, the management of fewer and fewer economic resources represents an important deterrent in ER preparation. In fact, as an information tool, prepared on a voluntary basis, the possibility of allocating a part of the economic resources available is an essential prerequisite to carry out activities such as identification, accounting and reporting. This consideration is corroborated by the results of the analyses, which show that the co-financing received from the European Commission was crucial for the launching of the initiative. In order to take care of environmental accounting and draw up the related ER, environmental-oriented governance is an indispensable prerequisite (Taliento et al., 2019).

In fact, even where economic resources have been allocated, without the right awareness of the considerable advantages deriving from the adoption of sustainability-oriented policies, LGs could hardly be encouraged to invest in the ER process. It has been highlighted the pivotal role of ER-related governance mechanisms in assessing the appropriateness of both substantive and policy-making processes, and in making judgements on the personal qualities of political actors. Political acts may be evaluated on the basis of prevailing normative standards, independent from formal rules and regulations (Schedler, 1999).

In the attempt to stimulate scholars and practitioners towards the acquisition of a complete awareness of the benefits deriving from the implementation of policies oriented to sustainability in its triple form, the interaction between governance factors should be further analyzed. Moreover, it would be interesting to investigate the relationship between ER and accountability in the context of ‘metagovernance’ (Meuleman and Niestroy, 2015). An area that explores how to combine different governance styles, established on different scales (global, national and local, for example), into successful governance frameworks. This could imply also a comparison between different countries, since governance settings are continuosly faced with challenges (e.g. unstable economic conditions and cultural diversity) that LGs and organizations in general, need to tackle. This further analysis could also require to understand how to institute the appropriate leadership, organizational structure and processes. For example, it might critically examine Information and Communication Technology (Hejase et al., 2016a) and emerging technologies (Agostino and Sidorova, 2017; Bellucci and Manetti, 2017) considering sustainable development issues. Thus, it would imply board members encouraging companies to point towards the potential of human capabilities approach also in terms of ethical education (Hejase and Tabch, 2012; Hejase et al., 2016b). These human-nature relationships issues would provide a site from which a route to raise counsciousness would be initiated also in the recent trend of accounting for sustainable development (Bebbington and Larrinaga, 2014).

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Agostino D, Sidorova Y (2017). How social media reshapes action on distant customers: Some empirical evidence. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 30(4):777-794.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Aiqin YLWST (2006). Corporate Governance, Accounting Environment and International Convergence of Accounting Standards. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Armstrong E (2005). Integrity, transparency and accountability in public administration: Recent trends, regional and international developments and emerging issues. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs pp. 1-10.

|

|

|

|

|

Armstrong CS, Balakrishnan K, Cohen D (2012). Corporate governance and the information environment: Evidence from state antitakeover laws. Journal of Accounting and Economics 53(1-2):185-204.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Arsel Z (2017). Asking questions with reflexive focus: A tutorial on designing and conducting interviews. Journal of Consumer Research 44(4):939-948.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bakre OM (2011). Corporate governance practices as a reflection of the socio-political environment in Nigeria. International Journal of Critical Accounting 3(2-3):133-170.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Baker M, Schaltegger S (2015). Pragmatism and new directions in social and environmental accountability research. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 28(2):263-294.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ball A, Grubnic S, Birchall J (2014). Sustainability accounting and accountability in the public sector. In Bebbington J, Unerman J, O'Dwyer B (Eds), Sustainability accounting and accountability, Routledge, New York pp. 176-196.

|

|

|

|

|

Ball A, Grubnic S (2007). Sustainability accounting and accountability in the public sector. In: Unerman J, Bebbington J, O'Dwyer B (eds.), Sustainability Accounting and Accountability, Routledge, London, UK. pp. 243-265.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ball A (2005). Environmental accounting and change in UK local government. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 18(3):346-373.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bartelmus P, Seifert EK (2018). Environment Statistics: Draft guildelines for statistics on materials/energy reports Report of the Secretary-General in Green Accounting, Routledge, London, UK, pp. 111-147.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bartocci L, Picciaia F (2013). Towards integrated reporting in the public sector. Busco C, in Frigo LM, Riccaboni A, Quattrone P (Eds), Integrated Reporting, Springer, Cham, U.K. pp. 191-204.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bebbington J, Unerman J (2018). Achieving the United Nations sustainable development goals. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 2018:1-25.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bebbington J, Larrinaga C (2014). Accounting and sustainable development: An exploration. Accounting, Organizations and Society 39(6):395-413.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bebbington J, Unerman J, O'Dwyer B (2014). Sustainability accounting and accountability, Routledge, New York, USA, pp. 176-196.

|

|

|

|

|

Becker SD (2014). When organisations deinstitutionalise control practices: A multiple-case study of budget abandonment. European Accounting Review 23(4):593-623.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bellucci M, Manetti G (2017). Facebook as a tool for supporting dialogic accounting? Evidence from large philanthropic foundations in the United States. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 30(4):874-905.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bennett M, James P (2017). The Green bottom line: environmental accounting for management: current practice and future trends. Routledge, London.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Borriello F (2013). The sustainability of Mediterranean Port areas: environmental management for local regeneration in Valencia. Sustainability 5(10):4288-4311.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Braam GJM, de Weerd LU, Hauck M, Huijbregts MA (2016). Determinants of corporate environmental reporting: The importance of environmental performance and assurance. Journal of Cleaner Production 100(129):724-734.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Brown LD, Moore MH (2001). Accountability, strategy and international nongovernmental organizations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 30(3):569-587.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Buhr N (2002). A structuration view on the initiation of environmental reports. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 13(1):17-38.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Buhr N, Gray R, Milne MJ (2014). Histories, rationales, voluntary standards and future prospects for sustainability reporting. Sustainability accounting and accountability, 51. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Chapple L, Dunstan K, Truong TP (2018). Corporate governance and management earnings forecast behaviour: Evidence from a low private litigation environment. Pacific Accounting Review 30(2):222-242.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

CLEAR (2003). Dalla contabilità alla politica ambientale: VV., Metodo CLEAR, Edizioni Ambiente, Milano.

|

|

|

|

|

Corcoran PB, Walker KE, Wals AE (2004). Case studies, makeâ€yourâ€case studies, and case stories: a critique of caseâ€study methodology in sustainability in higher education. Environmental Education Research 10(1):7-21.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Cormier D, Magnan M (2003). Environmental reporting management: A continental European perspective. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 22(1):43-62.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Crosby A, Robbins D (2013). Mission impossible: Monitoring municipal fiscal sustainability and stress in Michigan. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting and Financial Management 25(3):522-555.

|

|

|

|

|

Dalmazzone S, La Notte A (2009). L'applicazione dell'approccio NAMEA per emissioni in atmosfera e rifiuti speciali a livello regionale, provinciale e comunale. Economia Delle Fonti Di Energia E Dell'ambiente 3(1):61-86.

|

|

|

|

|

Debnath S (2019). Environmental Accounting, Sustainability and Accountability. SAGE Publications India, New Delhi.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Deegan C (2017). Twenty five years of social and environmental accounting research within Critical Perspectives of Accounting: Hits, misses and ways forward. Critical Perspectives on Accounting 43(3):65-87.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Dumay J, Guthrie J, Farneti F (2010). GRI Sustainability Reporting Guidelines for Public and Third Sector Organizations. Public Management Review 12(4):531-548.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Del Baldo M, Aureli S (2017). Sistemi di misurazione delle performance nelle reti pubblico-private del settore dei servizi turistici. Azienda Pubblica 30(2):119.

|

|

|

|

|

Del Bene L, Ceccarelli R (2016). Il contributo del Sistema Informativo alla gestione logistica dei materiali. Un caso di studio nel settore sanitario. Management Control 1:149-172.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Delreux T, Happaerts S (2016). Environmental policy and politics in the European Union. Macmillan International Higher Education, London.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Di Palma M, Falcitelli F, Femia A (2005). Environmental Accounting as a Tool for Defining and Assessing Public Policies. Società Italiana di Statistica-SIS (2005) Statistics and Environment-Invited Papers, Atti del Convegno intermedio "Statistics and Environment", Università di Messina, 21-23.

|

|

|

|

|

Dragomir VD, Anghel-Ilcu ER (2011). Comparative perspectives on environmental accounting elements in France and the United Kingdom. African Journal of Business Management 5(28):11265-11282.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Edwards T (2007). Ethical fitness for accountable public officials: An imperative for good governance. Journal of Public Administration 42(5):28-34.

|

|

|

|

|

Eisenhardt KM (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review 14(4):532-550.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Evangelinos K, Nikolaou I, Leal Filho W (2015). The effects of climate change policy on the business community: A corporate environmental accounting perspective. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 22(5):257-270.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Farneti F, Guthrie J (2009). Sustainability reporting by Australian public sector organisations: why they report? Accounting Forum 33(2):89-98.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Farneti F (2011). La rendicontazione di sostenibilità negli enti locali. Roma: Rirea.

|

|

|

|

|

Farneti F, Siboni B (2011). An analysis of the Italian governmental guidelines and of the local governments' practices for social reports. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 2(1):101-125.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Foucault M (1991). The Foucault effect: Studies in governmentality. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

|

|

|

|

|

Garcia-Torea N, Larrinaga C, Luque-Vílchez M (2019). Academic engagement in policy-making and social and environmental reporting. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal 11(2):281-290.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Georgakopoulos G (2018). Risk, risk conflicts, sub-politics and social and environmental accounting and accountability in scottish salmon farming. Journal of Economics and Business 68(2-3):3-38.

|

|

|

|

|

Giovanelli F, Coizet R, Di Bella I, a cura di (2005). Ambiente condiviso: politiche territoriali e bilanci ambientali. Edizioni Ambiente.

|

|

|

|

|

Goswami K, Lodhia S (2014). Sustainability disclosure patterns of South Australian local councils: A case study. Public Money and Management 34(4):273-280.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Greiling D, Traxler AA, Stötzer S (2015). Sustainability reporting in the Austrian, German and Swiss public sector. International Journal of Public Sector Management 28(4/5):404-428.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gray R, Owen D, Maunders K (1987). Corporate social reporting: Accounting and accountability. Prentice-Hall International. Not cited.

|

|

|

|

|

Gray R, Bebbington J (2000). Environmental accounting, managerialism and sustainability: Is the planet safe in the hands of business and accounting? Advances in Environmental Accounting and Management 1(1):1-44.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gray R, Adams CA, Owen D (2014). Accountability, social responsibility and sustainability: Accounting for society and the environment. Pearson Higher Education, New York.

|

|

|

|

|

Grubnic S, Thomson I, Georgakopoulos G (2015). New development: Managing and accounting for sustainable development across generations in public services and call for papers. Public Money and Management 35(3):245-250.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gummesson E (2003). All research is interpretive. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing 18(6/7):482-492.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

GRI (2002) Global Reporting Initiative: Guidelines. Available at

View

|

|

|

|

|

He B, Shao Y, Wang S, Gu Z, Bai K (2019). Product environmental footprints assessment for product life cycle. Journal of Cleaner Production 233:446-460.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hejase HJ, Hejase AJ, Mikdashi G, Al-Halabi A, Alloud K, Aridi R (2016a). Information technology governance in Lebanese organizations. African Journal of Business Management 10(21):529.

|

|

|

|

|

Hejase HJ, Hejase AJ, Mikdashi G, Bazeih ZF (2016b). Talent Management Challenges: An Exploratory Assessment from Lebanon. International Journal of Business Management and Economic Research 7(1):504-520.

|

|

|

|

|

Hejase HJ, Tabch H (2012). Ethics education. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Horton J, Macve R, Struyven G (2004). Qualitative research: experiences in using semi-structured interviews. In Humphrey C, Lee B (eds). The real life guide to accounting research: a behind-the-scenes view of using qualitative research methods. Elsevier, Oxford, UK. pp. 339-357.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hyndman N, McKillop D (2018). Public services and charities: Accounting, accountability and governance at a time of change. The British Accounting Review 50(2):143-148.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Jan van Helden G, Johnsen Å, Vakkuri J (2008). Distinctive research patterns on public sector performance measurement of public administration and accounting disciplines. Public Management Review 5:641-651.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Jepson P (2005). Governance and accountability of environmental NGOs. Environmental Science and Policy 8(5):515-524.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Johanson JE (2014). Strategic Governance in Public Agencies. In: Joyce P, Bryson JM, Holzer M (eds.), Developments in Strategic and Public Management IIAS Series: Governance and Public Management (International Institute of Administrative Sciences (IIAS) - Improving Administrative Sciences Worldwide). Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lambert C, Sponem S (2012). Roles, authority and involvement of the management accounting function: A multiple case-study perspective. European Accounting Review 21(3):565-589.

|

|

|

|

|

Lamboglia R, Fiorentino R, Mancini D, Garzella S (2018). From a garbage crisis to sustainability strategies: The case study of Naples' waste collection firm. Journal of Cleaner Production 186:726-735.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Laratta R (2011). Ethical climate and accountability in nonprofit organizations: A comparative study between Japan and the UK. Public Management Review 13(1):43-63.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Larcker DF, Richardson SA, Tuna I (2007). Corporate Governance, Accounting Outcomes and Organizational Performance. The Accounting Review 82(4):963-1008.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lehman G, Kuruppu SC (2017). A framework for social and environmental accounting research in Accounting Forum, Taylor and Francis, London, UK pp. 139-146.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lehman G, Morton E (2017). Accountability, corruption and social and environment accounting: Micro-political processes of change in Accounting Forum, Taylor and Francis pp. 281-288.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Li M, Song L (2018). Corporate governance, accounting information environment and investment-cash flow sensitivity. International Journal of Accounting and Information Management 26(4):492-507.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lodhia S, Stone G (2017). Integrated reporting in an internet and social media communication environment: conceptual insights. Australian Accounting Review 27(1):17-33.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lodhia S, Jacobs K, Park YJ (2012). Driving public sector environmental reporting: the disclosure practices of Australian commonwealth departments. Public Management Review 14(5):631-647.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Marcuccio M, Steccolini I (2005). Social and environmental reporting in local authorities: A new Italian fashion? Public Management Review 7(2):155-176.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Margerison J, Fan M, Birkin F (2019). The prospects for environmental accounting and accountability. China in Accounting Forum. Routledge. London. pp. 1-21.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mazzara L, Sangiorgi D, Siboni B. (2010). Public strategic plans in Italian local governments: A sustainability development focus? Public Management Review 12(4):493-509.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Meakin S (1992). The Rio Earth summit: summary of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development. Library of Parliament, Research Branch.

|

|

|

|

|

Menicucci E, Paolucci G (2018). Forward-looking information in integrated reporting: A theoretical framework. African Journal of Business Management 12(18):555-567.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Meuleman L, Niestroy I (2015). Common But Differentiated Governance: A Metagovernace Approach to Make the SDGs Work. Sustainability, Vol. 7.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Muserra AL, Papa M, Grimaldi F (2020). Sustainable development and the European Union Policy on nonâ€financial information: An Italian empirical analysis. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 27(1):22-31.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Niemann L, Hoppe T (2018). Sustainability reporting by local governments: A magic tool? Lessons on use and usefulness from European pioneers. Public Management Review 20(1):201-223.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ntim CG, Soobaroyen T, Broad MJ (2017). Governance structures, voluntary disclosures and public accountability: The case of UK higher education institutions. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 30(1):65-118.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Papaspyropoulos KG, Blioumis V, Christodoulou AS (2010). Environmental reporting in Greece: The Athens stock exchange. African Journal of Business Management 4(13):2693.

|

|

|

|

|

Ricci P (2016). "Accountability", in Farazmand, A. (Ed.), Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance, Springer, Cham.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Richards C, Reynolds MA, Dillard J (2016). Governance and reporting in a complex global environment. Universal Journal of Accounting and Finance 4(1):1-8.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Schaltegger S, Burritt R (2017). Contemporary environmental accounting: issues, concepts and practice. Routledge, London.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Schedler A (1999). The self-restraining state: Power and accountability in new democracies, Lynne Rienner Publishers, Colorado, U.S.

|

|

|

|

|

Sendroiu C, Roman AG (2007). The Environmental Accounting: An Instrument for Promoting the Environmental Management Theoretical and Applied Economics 8(513):45-48.

|

|

|

|

|

Skinner BF (1963). Operant behavior. American Psychologist 18(8):503-515.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Stanciu CI, Joldos A, Stanciu GF (2011). Environmental accounting, an environmental protection instrument used by entities. Economics 11(2):256-280.

|

|

|

|

|

Starkey K, Maden P (2001). Bridging the relevance gap: Aligning stakeholders in the future of management research British Journal of Management 12(1):3-26.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Steele AP, Powell JR (2002). Environmental Accounting: Applications for local authorities to quantify internal and external costs of alternative waste management strategies in Environmental Management Accounting Network Europe, Fifth Annual Conference, Gloucestershire:1-10.

|

|

|

|

|

Taliento M, Favino C, Netti A (2019). Impact of Environmental, Social, and Governance Information on Economic Performance: Evidence of a Corporate Sustainability Advantage from Europe Sustainability 11(6):1-26.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Thompson CJ, Howard R, Pollio HR, Locander WB (1994). The Spoken and the Unspoken: A Hermeneutic Approach to Understanding the Cultural Viewpoints That Underlie Consumers' Expressed Meanings Journal of Consumer Research 21(3):432-452.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Unerman J, Chapman C (2014). Academic contributions to enhancing accounting for sustainable development. Accounting, Organizations and Society 39(6):385-394.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Vassillo C, Restaino D, Santagata R, Viglia S, Vehmas J, Ulgiati S (2019). Barriers and Solutions to the Implementation of Energy Efficiency. A Survey about Stakeholders' Diversity, Motivations and Engagement in Naples (Italy). Journal of Environmental Accounting and Management 7(2):229-251.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Visconti LM (2010). Ethnographic Case Study (ECS): Abductive modeling of ethnography and improving the relevance in business marketing research. Industrial Marketing Management 39(1):25-39.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

WCED SWS (1987). World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future 17(1):1-91.

|

|

|

|

|

Wheeler D, Elkington J (2001). The end of the corporate environmental report? Or the advent of cybernetic sustainability reporting and communication Business Strategy and the Environment 10(1):1-14.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Williams B, Wilmshurst T, Clift R (2011). Sustainability Reporting by Local Government in Australia: Current and Future Prospects. Accounting Forum 35:176-186.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Woodside AG, Wilson EJ (2003). Case study research methods for theory building. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing 18(6/7):493-508.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Yin RK (1994). Case study research: Design and methods Third Edition (Applied Social Research Method Series 5). Sage publications.

|

|