The study examines the relationship between the Corporate Citizenship (CC) practices of leading firms in their industries and their level of advancement in CC. The study took a conceptual approach and used two cases not as empirical evidence but for illustration purposes. The main hypothesis was that CC practices of leading firms find expression from the fact that these firms tend to play two significant roles. First, leading firms in CC can set standards (pace-setting) of CC practice in their industry which would become a benchmark for other firms. Second, leading firms take up the challenge to catch up with the standards set by other firms in the industry in other aspects of CC where they are not leaders. The results show that the two cases used by the study have revealed how the CC practices of a leading firm in an industry under institutional isomorphism that manifests through pace setting, and catching-up can improve the general CC practices of an industry. As a practical recommendation, champions of CC like NGOs should target leading firms more as their practices are more likely to be replicated by other firms in the industry since the study has demonstrated that firms in the industry tend to copy leaders (innovators and early adopters) more than laggards.

A newcomer in the field of business and social issues would be bewildered by a number of different terms and definitions that imply similar or identical meaning such as Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), Business Ethics, Corporate Philanthropy, Corporate Citizenship (CC) among other terms (Valor, 2005). In that regard, the current study uses the terms CC which other authors could refer to as CSR.

CC has received increased attention from business, the media, and researchers (Valor, 2005). Yet CC like most of the terms in management is yet to receive a widely acceptable definition (Othman and Othman, 2014). As a result, we do not pretend to define what CC is since there is no generally accepted definition or even the most appropriate one. Nevertheless, the current study takes the definition of policy.

Policy makers define CC as a concept whereby companies integrate social and environmental concerns in their business operations and in their interaction with their stakeholders on a voluntary basis. In this concept, CC is viewed as the contribution that firms make to sustainable development, requiring them to commit to

balancing and improving environmental and social impacts without damaging economic performance (Williamson et al., 2006). In recent years, the concept of corporate social responsibility, which for the sake of this study is referred to as CC, has gained recognition and importance in both business and political settings. Social responsibility in Africa is something that is yet to take root to match what is already happening in Europe, North America and some parts of Asia and is still seen in terms of philanthropy (Ofori and Debrah, 2014).

This raises an important question: ‘what can drive social responsibility practices in Africa? This question is worth exploring since African business environment is so different from that in the western countries. There is not much movement of ethical consumers as seen in Germany which is evident in the shell case of trying to sink the Brent spar into the northern sea (Greyser and Klein, 1996). Consumers are still more driven by affordability (due to low purchasing power) and accessibility (due to poor distribution infrastructure, transportation logistics); and less by acceptability (ethical practice of firms). However, there is emergence of sustainability reporting in Africa, as Ernst and Young report that it has several drivers. These include a move by a range of stakeholders driving organizations to implement a more sustainable strategy; sustainability decision-making is moving to the board, the drivers and benefits of sustainability reporting are increasing in prominence. However, the same reports explicate that the responsibility for preparing sustainability report is not yet completely aligned with the strategic or executive function of corporate Africa. This leads to a basic question that is instrumental to the African context of CC: ‘what is driving CC that has led to its continued growth in importance and significance among academics and corporate Africa?’ This question is critical since the study opines that there are three key broad drivers of CC, that is business case, institutional drivers and managerial values.

This paper extends the institutional theory of CC by positing that one of the forces behind the continued growth in significance of CC among academics and business communities can also be associated with the CC practices of leading firms in their respective industries. This is what this study opines is one of the key drivers of CC in Africa in general and Kenya in particular. CC practices of leading firms CC are particularly appropriate given the fact that both state regulation and industry-self regulation could be necessary but not sufficient. In fact, many researchers have argued that corporations may not only resist the imposition of regulations by the state in the first place but may also seek to control or otherwise capture regulators in ways that bend them toward the will of the corporations they are supposed to oversee (Etzioni, 1989.;Bernstein, 2015;Vogel, 1989;Tolbert and Zucker, 1983). This is probable in Africa where some corporates are almost more powerful than the state as most of them in power have captured the institutions in these countries due to economic power. This means they own the largest corporations in the country where they are the head of state. Moreover, the very corporations can also undermine effective self-regulation. For instance, there are plenty of examples of corporations violating cartel agreements (Fama and Jensen, 1983)or refusing to abide by industrial benchmarks and standards for quality that have been set by industrial associations. A scandal in the U.S. accounting industry-an industry that has long set its own standards of acceptable business practice-is another example of industrial self-regulation gone awry. Moreover, according to Campbell (2007), some instances of industrial self-regulation have been devised not only to evade state regulation and other forms of external control but also to facilitate predatory and opportunistic rather than socially responsible corporate behavior. That is why the social responsibility of the leading firms in an industry could set precedence that would fill the gaps left by business case, state regulation as well as managerial values exuded by self-regulation.

In the extant literature, one of the basic questions about CC is: why does CC continue to grow in importance and significance among academics and business communities? In response to this question, some empirical studies with the aim to make a Business Case (BC) for CC have examined the relation between CC and corporate financial performance (CFP). The BC for CC refers to the rationale for the business community to advance the CC ´cause´. The BC refers to the bottom-line reasons for pursuing CC strategies and policies (Othman and Othman, 2014).

BC has investigated the relation between CC and corporate financial performance (Argenti, 2004; Gray and Balmer, 1998; Lee, 2008; MSteger, 2006; Schwaiger, 2004; Vagadia, 2012; Wagner and Schaltegger, 2004; Margolis and Walsh, 2003; Weber, 2008). BC led to the belief by these management disciplines that CC is fit for their business (Lee, 2008). Business case has not successfully demonstrated itself as a driver of CC. Empirical research aimed at proving that there is a positive relationship between Corporate Social Performance (CSP) and CFP has inconclusive results. These CSP-CFP studies have ended up with inconclusive results (Roman et al., 1999, Baron, 2010). One category shows a positive link between CSP and CFP, the second shows a negative link, and the third shows no link.

With regard to MVs, research has shown that the formal adoption and implementation of CC by corporations can also be associated with socially conscious values of organizational managers (Hemingway and Maclagan, 2004). This stream of research has empirically demonstrated that the cognitive frames, mind-sets, conceptions of control, or worldviews of corporate managers are important determinants of how managers run their firms (Aguilera and Jackson, 2003; Dore, 1983; Hall and Sosckie, 2001; Whitley, 2004). At the institutional level, powerful social and political forces encourage organizations to act more responsibly (Campbell, 2007).

The neglected institutional driver for CC

Apart from the business case for CC, managerial values and institutional drivers for CC already mentioned, previous research has not yet considered the contribution that could be made by CC practices of firms that are leading in CC in their respective industries. Since the business case for CC is still not clear, managerial value for CC in Africa is at the infant stage, while there are weak institutions as found out by Ofori and Debrah (2014). The study explores what could be the drivers of CC in corporate Kenya. It is worth noting that leadership of a firm is referred to as perceived leadership by the firm’s peers in the industry.

The contribution of CC practices of leading firms in an industry is likely to manifest in two ways. This is with regard to pace setting and catching-up. When a firm generally leads in CC, it sets the pace in most of the aspects by setting the industry standards that other firms strive to achieve and in the process the CC practices of the industry advance. On the other hand, since the firms that lead in overall CC performance are very unlikely to lead in all CC aspects, they push for being leaders and they need to keep their leadership position to catch-up with other firms. And in the process the CC practices of the entire industry are likely to advance. Following the same line of thought, Snider et al. (2003) noted that the most effective means of advancing CC is through corporate peer pressure. Industrial associations, whose job, in part, is to ensure that their members act in social responsible ways often undertake this. To better formulate this contribution, we shall borrow a leaf from New Institutional Organizations literature under institutional isomorphism theory proposed byDiMaggio and Powell (1983)and Greenwood and Meyer (2008)which form the core of the theoretical framework of the study.

Here, first the term institution is defined. Next, an institutional isomorphism theory of CC and the insights of CC of a leading firm in an industry as a CC driver are presented. The institutional isomorphism theory describes the conceptual understanding of how CC practices of leading firms in an industry through pace-setting and catching-up could advance CC practices. Institutions, by North's definition, are the basic rules of the road in an economy, including formal systems, such as constitutions, laws, taxation, insurance, and market regulations, as well as informal norms of behavior, such as habits, customs, and ideologies (North, 2004). According to North (2004), institutions are both formal and informal. Formal institutions are rules and regulations that are devised by human beings to achieve a certain goal. Informal institutions are conventions and codes of behavior (North, 2004).

Unfortunately, “We cannot see, feel, touch or even measure institutions; they are constructs of the human mind”. Nevertheless, institutions have power (North, 2004: 107). In fact, institutional forces determine what organizations come into existence, remain in existence and how they evolve (North, 2004).

Institutional isomorphism theory of CC

Institutional isomorphism is “the constraining processes that force one unit in a population to resemble other units that face the same set of environmental conditions” (DiMaggio and Powell, 1983). In their attempt to answer why organizations are very much the same in their effort to change themselves, DiMaggio and Powell (1983)found out that it is due to isomorphism mechanisms that take place through coercive, mimetic and normative processes. The three mechanisms of institutional isomorphism are explained below.

Coercive isomorphism

Coercive isomorphism results from both formal and informal pressures exerted on an organization by other organizations upon which they share the same industry. In fact, one of the foundational tenets of institutional theory is that in order to prosper, organizations must be congruent with their institutional environments (Meyer and Rowan, 1977; Meyer and Scott, 1983), their structures and services must align with the “cultural-cognitive belief systems and regulatory and normative structures that prevail in a given organizational community” (Baum and Rao, 2004). Organizations are forced into such alignment because it promotes their success and survival by increasing the commitment of internal and external constituents of organizations and activities, and allowing them to obtain resources (Meyer and Rowan, 1977; Stinchcombe, 1965).

These formal pressures from regulators and informal pressures from some firms in the industry (mostly the leading firms) enhance the institutionalization of an industry. Institutionalization of an industry refers to the adoption of certain practices by firms in an industry due to the informal and formal institutional pressures they face. Institutional pressures could be felt as a force, persuasion, or as invitation to compliance.

Mimetic isomorphism

Mimetic isomorphism is due to the fact that uncertainty is also a powerful force that determines the behavior of organizations. This is so because when organizational technological environment is uncertain (March and Olsen, 1976)when goals are ambiguous, or when the environment creates symbolic uncertainty, organizations may model themselves on other organizations. This is because these organizations face the challenge of gaining acceptance (Suchman, 1995). This happens when, upon embarking on a new line of activity, particularly one with few precedents elsewhere in the social order, organizations often face the daunting task of winning acceptance either for the propriety of their activity in general or for their own validity as practitioners. This “liability of newness” (Freeman et al., 1983; Stinchcombe, 1965)manifests itself when new operations are technically problematic or poorly institutionalized; early entrants must devote a substantial amount of energy in sector building. For instance, in the Mobile money case, there were some uncertainties with regard to regulation and best practices in the industry. This level of uncertainty pushed other firms in the industry to model themselves on Safaricom, the leading firm by customer base and also subscriber base for mobile money.

Normative isomorphism

Normative isomorphism stems primarily from professionalization. Organizations may hire staff from a particular institution due to the perception that staff trained from the institution has greater chances to perform well. In that regard, “the greater the reliance on academic credentials in choosing managerial and staff personnel, the greater the extent to which an organization will become like other organizations in its field” (DiMaggio and Powell, 1983). Moreover, “the greater the participation of organizational managers in trade and professional associations, the more likely the organization will be, or become like other organizations in its field”(DiMaggio and Powell, 1983). The theoretical background has now set the stage for illustrating the role of leading firms as a CC driver.

The role of leading firms as a CC driver

As stated earlier, a leading firm in an industry plays an important role in the institutionalization of the industry since it sets the norms, standards and codes of conduct. These norms, standards and codes of conduct manifested through coercive isomorphism become informal and formal pressures that face every firm that shares the industry with the leading firm. The pressure is even higher when there is some level of interdependence in the industry. The leading firms also set the socio-cultural expectations in which organizations that it shares the industry with are likely to operate.

Once a leading firm defined the norms and set standards of what is considered CC best practices in an industry, other firms in the industry may replicate the practices of the leading firm in order to survive and gain legitimacy (Suchman, 1995), which, in this study simply means gaining acceptance. There are several strategies for gaining legitimacy: (a) efforts to conform to the dictates of preexisting audiences within the organization’s current environment, (b) efforts to select among multiple environments in pursuit of an audience that will support current practices, and (c) efforts to manipulate environmental structure by creating new audiences and new legitimating beliefs. The firms in the industry being studied seem to pursue their legitimacy, in the context of institutional isomorphism, through strategy (a).

According to the argument of natural selection in population ecology, for an organization to be considered fit, it must have an evolutionary process of adaptation that ensures that only the best-performing organizations survive (Whetten and Aldrich, 1979; Comstock, 1979; Hannan and Freeman, 1977; McKelvey, 1982). The replication of the CC of leading firms in an industry in order for them to survive leads to advancement in CC depending on how socially responsible the leading firm is. Suppose, the leading firm is a social icon, firm with exemplary practices, it becomes a pace-setter, mechanism in CC advancement.

Uncertainty with regard to the management of corporate image or reputation in CC is an interesting phenomenon. It is what fosters mimetic isomorphism in CC strategy. As stated earlier, uncertainty is a powerful force because when the business environment is uncertain, organizations may model themselves on other organizations. Since there is a lot of pressure on organizations to practice CC, for instance, while the BC for CC has not yielded conclusive results on whether there is a positive relationship between CC and CFP, there is uncertainty on the business leaders since they cannot be sure of the benefits they can get from CC. In Africa it is even more difficult to find a relationship between CSP and CFP since there is still no significant number of ethical consumers. However, there is no business that can be perceived as socially irresponsible if what Nike and Shell went through are anything to go by.

In that regard, firms might be forced to adopt CC without being sure of its contribution to the profitability of the firm. This might make them practice what other players in the industry are doing in order not to be perceived as outliers in the industry. Assuming that this case exists in an industry, other firms in the industry are likely to turn to copying the CC practices of leading firms. Consequently, the CC practices of the leading firms in the industry will determine the behavior of other firms hence a driver for CC, at least in that industry.

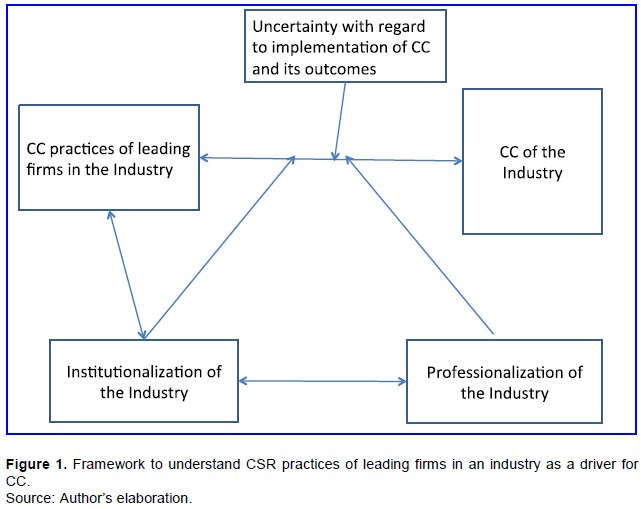

Since normative isomorphism, as stated earlier, stems from professionalization, it can also be a driver for CC by professionalizing it in an industry. This can be the case whereby firms in a given industry tend to hire staff from a particular academic institution. In such industries, the greater the reliance on academic credentials in staff selection, the greater the chances and extent to which an organization becomes like other organizations in this field. Since people are more inclined to replicate best practices, the dominant influence will come from the practices of the leading firms in the industry. In the case of CC, professionals hired in a given firm will tend to copy their colleagues whom they have a similar organizational schemas or cognitive framework by virtue of their academic formation in the same institution on how to make their firms socially responsible in a fashion that makes business sense. This could be due to the assumptions that the managers of the leading firms could be mentors or role models to the managers of other firms in the industry. Moreover, the greater the participation of organizational managers in trade and professional associations such as Business Marketing Associations (BMA) and Association of Finance Professionals (AFP), as stated earlier, the more likely the organizations will be like other organizations in the same industry. This is due to the mentoring roles of managers that head the leading firms in that industry as their counterparts see them as role models and innovators in the industry. The underlying idea is that managers seek to act in ways that are deemed appropriate by other managers and significant actors in their environment (Campbell, 2007). The above discussion leads to a framework that can be used to describe CC practices of leading firms in their respective industries as a driver for CC (Figure 1).

Two cases illustrating how the behavior of leading firms can be a CSR driver

Two cases of firms that lead in CC in their respective industries are presented here. The first case is EABL´s social innovation followed by M-Pesa (Mobile-Money) innovation by Safaricom, a leading Mobile Network Provider (MNP) in Kenya.

Corporate social innovation in East African Breweries Limited

Between 1998 and 1999, about 500 Kenyans died from adverse effects of illicit liquors, according to local media. Additionally, in November 19, 2000, the East African Standard reported that the death toll from the consumption of an illicit brew in the slums of Nairobi hit 132, with fears that the figure could rise as more people were hospitalized. Around the same time, The People Daily reported that at least 20 people had lost their sight, a story that was confirmed by the national referral hospital, Kenyatta National Hospital (KNH). These increasing rates of alcohol mortality and poisoning prompted EABL, the largest player in the beer market, to explore and assess ways of responding to this social predicament.

In December 2003, EABL launched a low-cost beer named Senator targeted at low-income consumers in Kenya. The decision was based on the realization that a significant portion of Kenyan alcohol market was divided between traditional brews and illicit liquors. These brews and liquors were leaving behind a trail of health problems on their consumers. Senator was targeted at the bottom of the pyramid (BOP) consumers. Despite being the market leader with a 95% market share in the branded beer market, EABL only held 44% of Kenya’s overall alcohol consumption. The rest of the market comprised non-branded alcohol products most of which were illegally produced and sold mainly to BOP consumers. But since the competitors (illicit liquor) for this socially responsible product (Senator) were charging very low prices it became very difficult for Senator Project to be economically viable for EABL. In fact in an effort to make it sustainable, EABL exhausted all its possible VAT tax concessions. The only option left for negotiation with the government was a reduction or waiver of excise duty on Senator. This entailed working in collaboration with several government departments and ministries among other players, for instance, the Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA), Ministry of Health, Ministry of Local Government, Kenya Association of Manufacturers (KAM) and Kenya Bureau of Standards (KEBS) among other stakeholders. KAM, in which most of the managers of EABL belong, was able to remind their colleagues of their social responsibility as the leading beer brewer in Eastern Africa.

EABL presented a case to the government for a waiver of excise duty on Senator. The thrust of EABL´s argument was that the government would save on the taxpayers’ money by reducing the resources used in dealing with illnesses and emergencies created by the consumption of illicit brews. Moreover, the government would start collecting some of the tax that was being lost from the sale of illicit brews – this category of drinks comprised 56% of the alcohol market in Kenya. KRA assessed the case and recommended that the request be granted. In late 2004, the government agreed to a 30% concession on excise duty tax on Senator rather than a total exemption. The concession was available to any non-malted beer manufacturer in Kenya. EABL, with regard to manufacturing process, was innovative turning Senator into a non-malt beer (brewed from barley) since malt beer attracts higher taxation from the government compared to non-malt beer. This made senator beer the world´s barley only brewing process. This reward opened the doors for other beer companies that wanted to replicate the production strategy of EABL, this time without having to spend time and resources in negotiating with the government on tax concessions and also experimenting. This incentive acted as a driver for more innovation in this direction hence enhancing the CC of the beer industry in Kenya as the alcohol related problems continued to diminish. Kenya moved from a drinking nation to a working nation.

Upon the lessons the government learnt from the social innovation of EABL, the government sponsored a bill in parliament to allow other alcohol companies to follow what EABL had done and at the same time to have more stringent rules to avert deaths caused by consumption of illicit brews. Among the companies that now follow a similar business model as EABL is Keroche Industries, which is among the fiercest competitor of EABL (See the case: Keroche Industries Take on Market Giant EABL). This is a healthy competition, caused by the behavior of EABL in the industry, and it improved the social responsibility of companies in the beer industry in Kenya as endorsed by the Ministry of Health.

M-PESA-Kenya´s Experiment with Branchless banking

M-PESA is a mobile payment solution provided by Safaricom, Kenya´s leading MNP. M-PESA facilitates a variety of financial transactions, including deposits, withdrawals, money transfers, loan payments, and bill payments through mobile phone and a network of agents that included airtime resellers and retail outlets acting as ‘banking agents’. The M-PESA service does not require users to have bank accounts. M-PESA, thus, served as a branchless banking service for Millions of Kenyans who did not have access to banking services. Since its introduction in March 2007, M-PESA had shown exceptional growth, with six Million customers having registered for the service, which were nearly half the customer base of Safaricom and an average of daily transaction volume of $ 1.96 million.

According to the judges of GSMA Global Awards 2009, M-PESA is:

“An accessible and intuitive solution, reflected by an unprecedented take-up rate for a service of this kind; M-PESA will serve as a blueprint for other operators around the world. Targeting the unbanked, this provides a simple means for people to safely transfer and carry money.”

This service was so innovative that it penetrated beyond microfinance. Microfinance had expanded the reach of financial services to the poor, the unbanked and the people in remote areas. Yet a vast segment of the populations remained outside the net of microfinance, primarily because of the transaction costs involved in serving them. A novel concept, ´branchless banking´ had thus emerged as one of the solutions to address this social problem (Appendix 1).

After close to two years of rapid and sustained growth (Appendix 2), there was the phase whereby lack of appropriate regulatory status-similar to that of a bank- inhibited the growth of M-PESA. Moreover, some experts had questions as to why M-PESA had not fully developed into a savings product since a number of its customers used it as a savings avenue and the fact that it had reduced the percentage of the unbanked in Kenya (Appendix 3). They had pointed out several plus points of M-PESA that render it most suitable for offering savings products. One, the number of M-PESA agents in Kenya was about 11 times more than the number of bank branches. Two, the absence of a monthly or maintenance fee and free deposit transactions made M-PESA more affordable than most other savings products. Three, a number of customers regarded M-PESA as a safe mechanism for storing their savings.

M-PESA was also beginning to face competition with the entry of new players. A major operator Zain, now Airtel, had entered the market in February 2009 with its mobile money product under the brand name ´Zap´, and another mobile operator, Orange, was also planning to come out with its money transfer product. Zap was marketed, more than just a mobile money service- it was promoted as “mobile wallet”, which could enable customers transfer money between their zap wallet and bank account. The pricing of Zap was also competitive vis-à-vis M-PESA. Unlike M-PESA, Zap customers had a recommended fee structure which allowed them negotiate the actual transaction fee with agents. Zap grew as rapidly as M-PESA. Safaricom responded by introducing other innovative products like M-Kesho, a money savings product and M-Shwari, which is just like a bank with an option for customers to access mobile loans and this trend continues. After over two years of rapid growth, M-PESA had some challenges at hand as it faced competition from other MNPs that replicated its strategy in the mobile money business segment.

As Safaricom continued to innovate to respond to the services needs of the Kenyan society, they realized more needs than innovative responses. This necessitated Safaricom, in partnership with Vodafone, to establish a training facility to build technological capacity to meet the needs of the fast-growing telecommunications industry, which lacks specialists with vital applications development skills for the economy.

1.Nike was accused of using child labor in the production of its soccer balls in Pakistan and this led to customer boycotts especially Fifa, one of their main customers which forced to company to undergo through significant turnaround in cleansing its name then being among the leading firms in CSR in the industry through the push from "not Just do it but Do it right." This can be seen further on http://www1.american.edu/ted/nike.htm and http://www.prwatch.org/node/6131 both accessed on 21st January 2011.

2 .Brent Spar, was a North Sea oil storage and tanker loading buoy in the Brent oilfield, operated by Shell UK. With the completion of a pipeline connection to the oil terminal at Sullom Voe in Shetland, the storage facility had continued in use but was considered to be of no further value as of 1991. Greenpeace organized a worldwide, high profile media campaign against this plan. http://www-static.shell.com/static/gbr/downloads/e_and_p/brent_spar_dossier.pdf, accessed on 21 January 2011.

3. http://www.marketing.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=1, January 21, 2011.

4. http://www.afponline.org/- January 21, 2011.

5.Illegally produced alcohol that are presumed dangerous due to the unhygienic production conditions

6.Brews which are mainly used for cultural purposes such as birth, initiation, marriage and funeral ceremonies

7. http://www.ratio-magazine.com/20080813127/News-Analysis/Keroche-Industries-Take-on-Market-Giant-EABL.html

8 . It news, http://www.itnewsafrica.com/2009/02/safaricom%e2%80%99s-m-pesa-service-wins-global-award/

9. Branchless banking did away with the conventional (traditional) system of branches to serve populations in different geographic zones. It used information and communications technologies and network of non-bank retail agents to reach customers instead of the brick and mortar branch model.

10. http://www.consumersinternational.org/media/165195/ourmoneyourrights-theevolutionoffinancialservicesinafrica.pdf (accessed on April 13, 2011)

11 . http://www.consumersinternational.org/media/165195/ourmoneyourrights-theevolutionoffinancialservicesinafrica.pdf

The two confirms our postulation that CC practices of leading firms is a driver for CC due to the fact that these firms tend to play two significant roles. First, EABL and Safaricom’s M-PESA set standards (pace-setting) of CC practices in their industry which would be a benchmark for other firms. Second, the two firms have also taken up the challenge to catch up with the standards set by other firms in the industry in other aspects of CC where they do not command the lead. These two roles make the CC practices of leading firms a driver for CC in their respective industries but, as illustrated in Figure 1, they are contingent on the level of institutionalization of the industry. This leads to coercive isomorphism, the level of uncertainty in the industry that triggers mimetic isomorphism, and the level of professionalization of the industry that ignites normative isomorphism. We now discuss how each of the types of isomorphism is evident in the two cases.

Coercive isomorphism

Coercive isomorphism was observed in both cases. Coercive, as already defined, results from both formal and informal pressures (norms) exerted on an organization by other organizations upon which they share the same industry; hence there is a level of interdependence among firms. With regard to social innovation at EABL, Senator Project can be categorized under 56% of the alcohol market that was unregulated. But after EABL produced the branded beer, Senator, other beer companies replicated EABL´s strategy, which entailed going by the informal norms EABL had created in that market segment. Additionally, learning from the socially responsible behavior of EABL, the government sponsored a bill in parliament to formalize the informal norms already established by EABL pushing other firms to comply.

In the M-PESA case, as stated earlier, Safaricom´s regulator (CCK) did not know how to regulate M-PESA. In fact, CCK, cautious that regulation could kill the innovation, left Safaricom to self-regulate while monitoring its behavior. During this period, the behavior of Safaricom with regard to M-PESA established the informal norms in the industry that were later replicated by new market entrants. The informal norms in the industry continued under the watch of the regulators who started formalizing some of the informal norms in the industry.

The other interesting aspect of coercive isomorphism came to play when Orange was to launch itself as a MNP. The management feared that since both Safaricom and Airtel, apart from being MNP also offer mobile money services, Orange would not be taken seriously should they not follow the norm, which is to include mobile money services in their business model. Yu, another MNP faced the same dilemma. In that regard, it is evident that the leading firms in the context of coercive isomorphism can produce a means through which CC practices can be enhanced. This can be in a semi-voluntary environment since leading firms impose informal norms upon themselves and upon the industry and their regulators can formalize them. Therefore, with regards to coercive isomorphism, the two cases illustrate how the behavior of the leading firm can affect the behavior of other firms in the industry of which if they were socially responsible it can lead to better CC practices of individual firms and consequently the CC of the entire industry. These informal means that later become formal means of institutionalizing socially responsible behavior could be more effective in developing countries than regulatory approach; which are actually being implemented in India with very little impact. In India companies are required to spend around 3% of their pre-tax profit on social responsible activities.

Mimetic isomorphism

Mimetic Isomorphism was clearly observed in the M-PESA case. As stated above, mimetic isomorphism takes place when there is high level of uncertainty in an industry with regard to either technological or regulatory environment. In the case of mobile money, the regulators (CCK and CBK) did not know exactly how to regulate the business; therefore, the innovator firm, Safaricom was allowed to self-regulate. There had been no such an innovation in developed countries where Kenyan regulators could learn from, as is always the norm of developing countries learning from how developed countries dealt with the regulation of their innovations. There was increase in the level of uncertainty in the industry to the extent that other MNPs that decided to launch mobile money services had to follow the informal norms established by Safaricom. This means that to the extent that Safaricom was socially responsible, its behavior as the leading firm determined the CC practices of the industry, hence a driver for CC.

Normative isomorphism

Normative isomorphism takes place due to the professionalization of an industry especially when firms hire their employees from certain academic institutions, attaching importance to academic credential, and also when the managers of a firm belong to professional associations. These were observable in the two cases. In the EABL case, we observed that most managers of EABL belong to Kenya Association of Manufacturers (KAM) since EABL is a manufacturing firm. We also observed that KAM had a position on the social responsibility of EABL as a leading firm in the beer industry, which was to provide the BOP market with safe affordable alcohol that would solve the social problem of death due to consumption of cheap dangerous alcohol. Kenya Association of Marketers gave them some insights and also gave their social responsibility position with regard to the role of the beer industry.

With regard to reliance on academic credentials and hiring firms from the same academic institution, the Safaricom case that was highlighted became clearer. Safaricom train graduates on software development that would enable the telecommunications industry respond to the needs of the industry. This training is done in one particular university; arguably the leading university in Kenya, which has a tradition of social responsibility built on religious values since it is a religious university run by Opus dei. It is unlikely that these graduates will all work only for Safaricom after completing their Msc. TID. They will probably work for other MNPs like Airtel, Orange, Yu where they will carry their socially conscious mindsets they acquired in Safaricom academy. Some of them may also join the same professional association from which they will continue to share insights. In the end, the telecommunications industry will be more professionalized, hence normative isomorphism with regard to CC practices of the leading firms, Safaricom and EABL.

Pace setting and catching up

There are two significant roles that leading firms play that lead to the advancement in CC of an industry (pace-setting and catching up). These roles are also observable in the two cases. Pace-setting role is seen in establishing the informal norms through coercive isomorphism as already discussed. Catching up behavior is observable more clearly in the M-PESA case. This was apparent in how Safaricom’s competitor, Zain, now Airtel, had entered the market with the mobile money product that added more value beyond what M-PESA offered. This is evident when Zap was marketed, more than just a mobile money service- it was promoted as “mobile wallet”. The pricing of Zap was also competitive vis-à-vis M-PESA.

By Zap being packaged as mobile wallet, Safaricom was challenged and had to catch-up with the progress made by its competitor Airtel. This challenge brought to Safaricom´s attention the question that had been raised by some experts as to why M-PESA had not fully developed into a savings product. Safaricom responded to the challenge of having to catch-up by launching M-KESHO and later M-shwari. M-KESHO is a package of financial product issued by Equity Bank that runs on the M-PESA transactional rails. The core product is a savings account, but account holders can also tap into loan and insurance facilities.

http://financialaccess.org/node/2968