Full Length Research Paper

ABSTRACT

The objective of this study is to identify the factors that prevent Cameroonian companies from being listed on the Central African Stock Exchange (CASE), despite their difficulties in obtaining funding through bank loans or other external sources of finance. Based on semi-structured interviews conducted with six (6) managers of Cameroonian public companies, several factors blocking the listing of companies on the stock exchange were identified. Some of these factors are inherent to CASE it and others are linked to the companies or public authorities. By identifying these different factors that inhibit the willingness of companies to go public, this study makes a scientific contribution to the debate on corporate finance. It also fills a gap by shedding light on the contrast between the need to finance investments and the lack of interest in the financial market, even though these companies are faced with insufficient financial resources. At the managerial level, the results obtained constitute a challenge for the Cameroonian public authorities, stock exchange authorities and business associations to work on supporting and encouraging companies to go public, but also to adapt the conditions of access to the stock exchange by taking into account local realities.

Key words: Initial public offering (IPO) - Central African Stock Exchange (CASE), barriers, Cameroonian companies, Lack of information.

INTRODUCTION

Funding is a major concern for businesses in general and those in Cameroon in particular. Indeed, throughout their existence, enterprises face two major challenges: the choice of profitable investments and the funding of these investments. If the investment decision is an endogenous factor for the company, access to funding appears not to depend entirely on the company. The latter may well choose the most profitable investments, but if these are not funded, the company will not be able to implement them; hence the need for funding in the life and development of companies.

This need for funding is highly felt in businesses operating in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) in general and in Cameroon in particular. In this regard, Lefilleur (2009) notes that difficulties in accessing funds are the primary obstacle to the development of SMEs in SSA, far ahead of problems of corruption, deficient infrastructure, or abusive taxation. Eniola and Entebang (2015) and Abor and Quartey (2010) indicate that access to finance remains one of the major obstacles faced by SMEs in SSA. BIT (2013) points out that in the CEMAC zone, access to credit is the major obstacle for both cash flow and investment financing.

In the case of Cameroon, Essomba and Omenguele (2013) note that the weakness of SMEs' equity capital is widespread. Also in Cameroon, a survey carried out by the Ministry of Small and Medium Enterprises, Social Economy and Handicrafts (MINPMEESA) in 2009 with funding from the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) reveals that nearly 77.1% of Cameroonian SMEs have difficulties accessing bank financing (Molou et al., 2018). Fouda (2009) and Wanda (2007) point out that despite their excess liquidity and the restructuring of the Cameroonian banking sector initiated in the late 1980s, banks do not always grant the credits requested by businesses. The Central African Banking Commission (COBAC) in its 2018 report confirmed this excess liquidity of banks in Cameroon. In the same vein, The World Bank (2008, 2009), in Doing Business 2009 and 2010, reports that businesses in Cameroon have fallen from the 132nd position in 2009 to 137th in 2010 in terms of obtaining bank loans, indicating a decreased access to funding for enterprises.

In such a context, resort to the financial market becomes unavoidable. "Indeed, the IPO ensures a significant inflow of funds, increases the company's reputation, and negotiating power with its various partners (Levasseur and Quintart, 1998), increases the mobility of capital (Saada, 1996), controls the managers (Daigne and Joly, 1986), and favours external growth strategies (Levasseur and Quintart, 1998; Fadil, 2005). It was precisely with a view to broadening the range of funding for Cameroonian companies that the Douala Stock Exchange (DSX for short) was created in December 2001. Unfortunately, from 2001 to 2019, this stock exchange has only recorded three (03) IPOs in the equity segment:

Société des Eaux Minérales du Cameroun (SEMC) in 2006, Société Africaine Forestière et Agricole du Cameroun (SAFACAM) in 2008, Société Camerounaise des Palmeraies (SOCAPALM) in 2009. Even its merger/absorption with the Bourse des Valeurs Mobilières de l'Afrique Centrale (BVMAC) to create a single financial market for Central Africa did not improve the situation. The new company known as the Central African Stock Exchange (BVMAC) has only five (05) companies listed, namely the three (03) companies from the DSX, the Investment Company for Tropical Agriculture Gabon (SIAT GABON) which has been on the BVMAC since 2013 and the Regional Savings and Credit (LA RÉGIONALE) which entered in 2021. Thus, even the will of the Heads of State and Government of Central Africa to boost this financial market has not produced the expected effect. It is this contrast between the difficulties of access to funding for companies and the low level of listing on the stock exchange that led us to ask the following question: Faced with their funding difficulties, why do Cameroonian companies not take advantage of the alternative offered by the Central African Stock Exchange (BVMAC)? More precisely, what are the obstacles to the listing of Cameroonian companies on the BVMAC? The search for answers to these questions has led us to address the following topic: "Financing by the stock exchange market: On the quest for impediments”.

It should be noted that there is a lot of work on IPOs. Particularly in the African context, the recurrent question is whether the financial market really constitutes a serious alternative to the banking market. In an attempt to answer this question, Jemaa (2008), in his work in Tunisia, concludes that the particularities of the African company (family ownership, culture of concealing financial information, preference for funding by equity or family funds, dominance of SMEs, etc.) influence its financial behavior and are not adapted to funding by the stock exchange market. While it is true that these factors are likely to inhibit the listing of companies on the stock market, it should be noted that these same factors are present in other companies that manage to go public. Indeed, Korichi and Mdaghri (2018) note that in 2016, forty-six family-controlled companies and thus almost 61.33% of the companies listed on the Casablanca Stock Exchange are family-owned. Luo and Liu (2014) report that in 2008, the Chinese stock exchange market had 387 family-owned firms, representing 34.43% of all listed non-financial firms. Sraer and Thesmar (2007) points out that family firms account for almost half of the top forty market capitalizations in France and one third of the five hundred in the United States of America. Moreover, in these countries, where there are many IPOs, there are financial scandals. The cases of Olympus, Toshiba, Fuji-Xerox, Sharp, Crédit Lyonnais, and Enron show that the concealment of financial information is not restricted to certain countries. Moreover, the dominance of SMEs is almost a general phenomenon. In all countries, there is a high proportion of SMEs. In this respect, Molou et al. (2018:131) note that "small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) occupy more than 88.5% of all African enterprises, of which 70% to 80% are micro and very small enterprises that provide nearly 60% of jobs". In 2017, 99% of French companies were SMEs, 94% of which were microenterprises. It is therefore reasonable to think that, apart from the known factors, there are others that need to be identified (Djoumessi et al., 2020).

The objective of this study is to identify the factors that prevent Cameroonian companies from financing themselves through the stock exchange market, despite their difficulties in financing their activities through bank loans or other external sources of financing. The interest of this study is to elucidate the contrast between the need to finance investments and the lack of interest in the financial market, even though these companies have insufficient resources.

To achieve this objective, this work was organized into five parts besides the introduction. The first and second parts are devoted to the literature review covering the presentation of the Central African Stock Exchange and the analysis of the theories underlying the listing of companies on the stock exchange, the third to the methodology used the fourth to the main results and the fifth, to their interpretation.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The stock market is a major role in corporate financing. It has been the subject of numerous studies that have made it possible to identify theories that explain its functioning and the behaviour of economic agents towards it. In this part of our work, we will focus on the Central African Stock Exchange, our study framework, and the theories that can be used for an in-depth study of a stock exchange.

The Central African Stock Exchange (CASE): History, organization, and functioning

The Douala Stock Exchange (DSX) is the first stock exchange in Cameroon. This stock exchange was created by Law No. 99/015 of 22nd December 1999, which also governs its functioning. However, it was set up in December 2001 and officially inaugurated on the 22nd of April 2003. DSX was located at the SOCAR building in Akwa, in the city of Douala.

It was a public limited company with a board of directors and a share capital of 1.8 billion CFAF. 63.7% of this capital was in the hands of ten (10) commercial banks and two (02) financial companies, namely: Banque Atlantique, Afriland First Bank, Banque Internationale pour le Commerce, l'Epargne et le Crédit, Commercial Bank of Cameroon, Société Camerounaise de Banque, Société Générale Cameroun, Standard Chatered Bank Cameroon, Union Bank, as far as banks are concerned, and Crédit Foncier du Cameroun, Netherland Development Finance Company, for financial companies are concerned; 23% by the splitting off of the State (Autonomous Sinking Fund, National Social Insurance Fund, Caisse de Stabilisation du Prix des Hydrocarbures, National Investment Fund); 13.3% by insurance companies, notably: Activa Assurances, Cameroon Insurance, Pro Assur, Compagnie Professionnelle d'Assurance (CPA), Société Africaine d'Assurance et de Réassurances (SAAR), Satellite Insurance.

The DSX had the following missions: to create, organise, and run the stock exchange market; to ensure the regular operation of negotiations on this market; to administer the negotiation of public negotiable instruments; to set the rules governing access to the market, admission to listing, the organisation of transactions and markets. It had three (03) compartments, namely: the equity compartment, the bond compartment, and the over-the-counter compartment reserved for entities whose capital securities (shares) or debt securities (bonds) are not listed on the official list, and negotiable public instruments. The DSX operated on the principle of cash, centralised, and order-driven market. The securities were quoted at the fixing.

DSX was officially absorbed by CASE on the 26th of September 2019. The two entities now form a single stock exchange company called the Central African Stock Exchange (CASE). CASE is a public limited company with a share capital of 6,842,900,000 CFA francs. This capital is distributed as follows: 47.15% for public companies, 34.87% for stock exchange companies, 07.21% for insurance companies, and 10.84% for others.

BVMAC has three (03) compartments: Compartment A for Large Companies, Compartment B for Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) and Small and Medium Industries (SMIs), and Compartment C for the bond market.

To be admitted to Compartment A, one must:

1) Be a joint stock company;

2) Introduce at least 20% of its capital on the stock exchange, with at least 10% of which must be provided to the public, unless an exemption is granted;

3) Have a market capitalisation of more than 10 billion CFA francs;

4) Have a turnover of more than 5 billion CFA francs;

5) Have at least 500 million CFA francs of equity capital;

6) To have recorded lucrative results for two (02) consecutive years, unless an exceptional exemption is granted; and

7) Must have certified the annual accounts of the last two (02) years.

In addition to these main criteria, other so-called ancillary criteria are also taken into account. These include dividend payout, margin rate, and turnover growth, existence of a business plan, sustainable debt, level of trade receivables and payables, profitability, return and solvency, transparency, organization, control and governance, and the liquidity contract. The assessment of these criteria is based on the fundamentals of the issuing company's sector of activity.

As for Compartment B, to be admitted to it, one must:

1) Be a joint stock company;

2) Introduce at least 20% of its capital on the stock exchange, of which at least 10% must be made available to the public unless an exemption is granted;

3) Have a market capitalization of less than or equal to 10 billion CFA francs

4) Have at least 200 million CFA francs of equity capital;

5) Have a turnover of more than 1 billion CFA francs;

6) To have made a profit for two (02) consecutive years, except in exceptional cases; and

7) Must have certified the annual accounts of the last two (02) years.

In addition to these main criteria, the following additional criteria was also found: margin rate, turnover growth, dividend distribution, sector and business prospects (business plan), sustainable debt, trade receivables and payables, profitability, return and solvency, transparency, organization, control and governance, and liquidity contract. As in Segment A, the assessment of these criteria is based on the fundamentals of the issuing company's sector of activity.

As for the compartment C dedicated to bonds, the access conditions are the following:

1) Be a private company, a State or a public body;

2) Solicit a minimum loan of 250 000 000 CFA francs;

3) Distribute at least 25,000 securities;

4) The loan requested must have a minimum duration of 03 years; and

5) Have a guarantee or rating.

In addition to these main criteria, there are also the following subsidiary criteria: margin rate, turnover growth, business prospects (business plan), sustainable debt, profitability, return and solvency, transparency, organization, control and governance, liquidity contract, debt ratio, repayment capacity, financial structure and liquidity.

It is thus understood that on the CASE, companies can use shares or issue bonds. However, taking into account both the main criteria and the secondary criteria, we conclude that the CASE is intended for profitable and solvent companies. It does not offer a place to companies in difficulty. However, this should not lead to the current situation where only five (05) companies are listed. Therefore, the reasons for the very low level of interest of companies in this financial market should be sought elsewhere than in the access conditions alone.

Listing of companies on the stock exchange: Theoretical frameworks and reading of lessons from the realities of listings

According to Giraud (2001) and Priolon (2012), financial markets are markets on which financial instruments are traded. The stock market is the compartment of the financial market that ensures the meeting between the buyers and sellers of financial securities according to various modalities (contracts) and the regular listing of the latter (Goyeau and Tarazi, 2006; Priolon, 2012). Two main types of securities are traded here: shares and bonds. A share is a moveable, dematerialized, and freely tradable property security on the stock exchange. It is a fraction of the company's share capital that gives its holder a right of ownership. A bond, on the other hand, is a negotiable debt security issued by private or public companies, governments, public authorities, or financial institutions. It represents a loan contracted for a specific amount and duration.

Long perceived as a simple stage in the life of a company, the initial public offering (IPO), which began in the late 1980s, has attracted the attention of many researchers. Their work has made it possible to identify several theories to explain why companies resort to financial markets and to highlight several related lessons. This study will in turn analyze the hierarchical financing theory, the agency theory, the signal theory, and the behavioral model of timing and life cycle theories as we feel these can appropriately guide our research work.

The IPO of companies in the light of the theory of hierarchical funding

The theory of hierarchical funding or Pecking Order Theory, developed by Myers and Majluf (1984), is based on the asymmetry of information between the managers of companies and their financial partners. For these authors, the hierarchical order of companies funding should be as follows: Self-financing/debt/issue of new shares. According to this hierarchy in the use of sources of funding, joining the financial markets is the last resort of companies.

This hierarchy in the choice of sources of funding for the company is a result of the constraints associated with it. In this respect, authors who have looked at the constraints that companies face in the context of an IPO focus on the direct and indirect costs associated with the IPO or the stay on the stock exchange. Thus, according to Sassi (2016), direct costs related to the IPO include legal fees, guarantor's fees, and the costs of advertising the transaction. Indirect costs are those related to the loss of control of the company due to capital dilution and to the effort and work of the management team to carry out the operation and launch financial communication. In addition to these explicit indirect costs, there is an implicit cost related to the under-evaluation of the offer price.

The costs of being listed on the stock exchange are linked to the company's obligation to keep the public regularly informed of its financial situation and of any decision that may affect its assets (fees of the auditors who certify the accounts as well as the costs of publication in the official bulletin of the stock exchange), the costs of keeping the shares and brokerage fees, and the costs of setting up and running the department in charge of shareholder relations (Jobard, 1996; Jacquillat, 1994).

Moreover, stock market funding obliges companies to be transparent and to disclose strategic information (Chemmanur et al., 2010; Fadil, 2016). It is also a means of controlling managers and directing their strategic conduct towards maximizing shareholder value (Jensen, 2002; Fadil, 2016).

Fundamentally, an IPO is a demanding means of financing. It is even more so when the company does not have a culture of transparency. It is certainly for this reason that the theory of hierarchical financing recommends resorting to it when other sources of financing are exhausted.

Reading the IPO through the agency theory

The functioning of the company is sometimes marred by opportunistic behaviour that can lead to agency conflicts. Even in family businesses, considered by some authors to be free of agency conflict, it is always present. In this regard, Schulz, Lubatkin, and Dino (2001) quoted by Fadil (2005:131) assert that “owner-managers expose firms to moral hazard, especially when they are freed from the discipline of markets”. It should be noted that an owner-manager can take advantage of his/her position to give him/her undue benefits at the expense of other shareholders. He can also exploit his subordinates. This is what Perrow (1986) calls owner opportunism. He may even act against his own economic interests. This is known as 'agency problems with one self' (Jensen, 1998). In the same vein, Simon (1993) and Eshel, Samuelson, and Shaked (1998), all cited by Fadil (2005:131), report that "altruism encourages parents, who are business owners, to give priority to their children, encourages family members to take others into consideration and makes family relationships so valuable that they promote and support family commitments at the detriment of the firm's interest". The IPO can then help to resolve these agency conflicts. Indeed, "the demands and constraints that the financial market imposes on managers push them to be more cautious in the strategic choices they make, and to put the interests of shareholders at the heart of their management concerns (Djoumessi et al., 2020:106). The IPO would be, so to speak, a means of governance of agency conflicts. A “spontaneous and non-specific mechanism forces managers to make effective strategic decisions”. This is as true for large companies as for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), for family and non-family businesses. This point of view is supported by Bouazza (2016) who indicates that the stock exchange is a means of improving the management of companies because of the possibilities it offers for economic agents with financial resources to take control of them or to index the remuneration of managers to their performance. The IPO also allows companies to reduce monitoring costs and to solve the problem of agency and information asymmetry between shareholders and managers (Jillali and Belkasseh, 2022; Bouazza, 2016; St-Pierre and Beaudoin, 1995).

The IPO allows companies to benefit from a reduction in their cost of capital, which may be attributed to tax effects, a reduction in agency costs, or information asymmetry. This reduction in costs can also be explained by the reduction in short-term debt in the funding of companies that are more expensive by nature (St-Pierre and Beaudoin, 1995). It can also be explained by the fact that the IPO, by diversifying the company's sources of financing, increases its negotiating power vis-à-vis credit organisations, which may enable it to obtain capital at lower costs. Moreover, in bullish periods, the company can use the favorable market climate to obtain capital at advantageous costs (Chaouni, 2009; Jacquillat, 1994).

Furthermore, an IPO company "benefits from continuous valuation and assessment by stock market experts, which limits the possibility of making additional gains and profits in a discreet way in case of a loss in the value of the company" (Jillali and Belkhasse, 2007:5). (Jillali and Belkasseh, 2022:213). The IPO also protects potential financiers from expropriation by entrepreneurs and increases their willingness to give up funds in exchange for shares, and thus broadens the scope of capital markets (Jillali and Belkasseh, 2022).

Thus, in addition to solving the problem of funding and improving the company's reputation or facilitating the sale of shares by their owners, the IPO appears to be a means of improving corporate governance.

Reading the IPO through the signal theory

The signal theory, initiated by Ross (1977), is based on the irregularity of information between the principal and the agent and analyses the operating mechanisms of financial markets. "Since listed companies are generally seen as benchmarks because of the requirements for listing and maintaining a listing, the choice to list and especially the propensity to perform well on the stock exchange market constitutes an important signal for its various partners, especially the financial by Djoumessi et al. (2020:107-108). Some authors have confirmed this good signal sent by the listing in favour of the company. In this regard, Stoughton et al. (2001), quoted by Djoumessi et al. (2020) show that the listing operation could signal the good quality of the company's products, and make it better known (Demers and Lewellen, 2003; Reese, 2003). In this context, product market advertising, IPO marketing, and undervaluation are levers of an overall strategy of disclosing information about product quality and firm value (Chemmanur and Yan, 2004, cited in Djoumessi et al., 2020), As a result of these communications, the listed company will quickly see its image and credibility affirmed with banks and suppliers (Szpiro, 1996). Moreover, as Chaouni (2009) notes, the effect of being listed on the stock exchange is to include the company in a 'Club' to which is attached a label of quality of information which increases the notoriety of the company. For Demers and Lewellen (2003), the listing on the stock exchange increases the visits to its web pages. Reese (2003) emphasizes that the IPO arouses the interest of the press in the company, which improves its knowledge by the public as well as that of its products, and consequently its reputation.

It can therefore be concluded that the IPO, by improving the company's reputation, makes it possible to reduce its financing costs by strengthening its bargaining power vis-à-vis banks and to access certain sources of funding that were inaccessible to it before its IPO (Pagano et al., 1998).

Reading the IPO through the behavioural model of timing and life cycle

According to the precepts of the optimal debt ratio theory, companies should aim toward an optimal financial structure. This optimal structure is the one for which the benefits and costs are equal. The existence of such an optimal financial structure would then allow firms to act in a predictable way in order to obtain such optimality (Modigliani and Miller, 1963; Myers and Majluf, 1984). "It arises from a trade-off between the gains of diversification for the manager, the irreversible cost of losing control through a friendly bid, and the direct costs of going public (Tchapga Djeukui, 2021:84).

In this regard, and with reference to the behavioural model of timing and life cycle, Beau et al. (2006) believe that “managers might consider an IPO when their company has reached a stage in its life cycle in which external equity can help it achieve an optimal financial structure" (Tchapga Djeukui, 2021:83). Thus, there are "periods in the life of a company that are more favorable for an IPO than others. Companies can therefore take advantage of these periods in order to strategically choose the right time to go public" (Djoumessi et al., 2020:108).

Therefore, for proponents of the behavioral model of timing and life cycle, the IPO should only occur when the company has reached a sufficiently advanced stage of maturity (in terms of size and age) and growth and a high level of available information (Berger and Uddell, 1998; Brian et al., 2005; Mac an Bhaird and Lucey, 2011; Fadil, 2016). Indeed, this theory reveals that the order of financing for firms, especially small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), should be as follows: internal financing, business angels, venture capital, short-term bank or commercial debt, long-term debt to financial institutions, and equity financing (Berger and Uddell, 1998; Mac an Bhaird and Lucey, 2011; Fadil, 2016). As in the theory of hierarchical funding, the stock exchange market is presented here as the last resort for companies when all other sources of funding are exhausted.

Generally, like any model, the IPO has its reverse side.

This is certainly what makes some authors (Latham and Braun, 2010; Chang, 2004) say that going public is a risky decision that must be carefully thought out, especially for SMEs (Fadil, 2016).

METHODOLOGY

The main objective of this study is to identify the factors that prevent Cameroonian companies from seeking finances through the stock exchange market, despite their difficulties in funding their activities through bank loans or other external sources of funding. In this exploratory research, the focus was on the Board of Directors, which is the main actor in the decision to list companies on the stock market, and the main managers (general manager, administrative and financial director) of companies who are aware of the concerns of their structures.

To conduct this research, the case study method was chosen, since we are interested in an unusual phenomenon in terms of the contrast created by the lack of interest of companies in the stock market, though facing difficulties in accessing finance. In such a context, only an in-depth study of specific cases can allow us to apprehend and understand the phenomenon (Hlady-Rispal, 2002).

The cases presented in this study are made up of the members of the boards of directors and the main managers (managing director, administrative, and financial director) of the joint stock companies that then represent our unit of analysis. For the selection of cases, the database of the National Institute of Statistics was relied on and more specifically on the Directory and Demography of Modern Enterprises (Institut National de la Statistique, 2018). This database shows a total of 1,032 Public Limited Companies (PLCs). In addition to the legal form of the company, we chose to hear from board members of listed companies and those of unlisted companies, which could nevertheless be listed according to the criteria for a stock market listing. The choice of the case also took into account their availability to participate in the data collection process.

For data collection, semi-structured interviews were conducted using a thematic interview guide. The interview guide included four (04) main points: (1) knowledge of the Central African Stock Exchange; (2) presence or absence of the company on the said Stock Exchange; (3) reasons why the companies do not list on the Central African Stock Exchange; and (4) measures to be taken to promote the listing of companies on the Central African Stock Exchange.

We carried out the data collection. The interviews took place in February and March 2022. These interviews were conducted with eight managers of eight Cameroonian companies. However, some managers did not give reasons for the reluctance of the companies to be listed or the measures to be taken to promote their listing on the stock exchange, which are our main concerns in this study. They were therefore not ultimately considered in the study. Thus, we ended up with six cases corresponding to six companies.

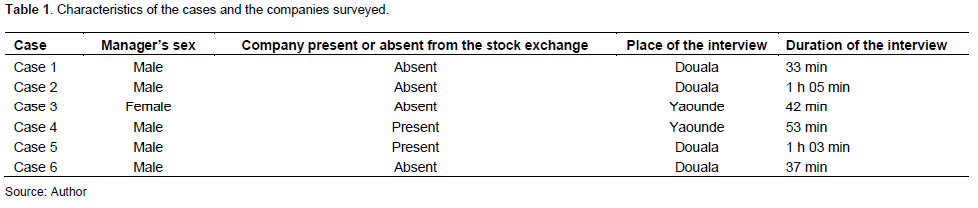

Each interview was recorded entirely using a tape recorder. The individual interviews lasted between 33 min and 1 h and 5 min. Summarily, the cases studied and the duration of the interviews are as shown in Table 1.

It should be noted that the interviews were conducted in Yaounde and Douala. This is justified by the fact that these two cities account for 57.4% of the companies in Cameroon (Institut National de la Statistique, 2018). Moreover, the companies involved in this study fall into several branches of activity. This diversity can be a source of rich information on the reluctance of Cameroonian companies to be listed on the stock market and the measures to encourage their listing.

With regard to the number of cases to be retained, it should be noted that authors seem to be divided on this subject. For Yin (1994), any number of cases lower than four does not prevent the objective of the study from being achieved.

For Eisenhardt (1989), the number of cases should be between four and ten. When it is less than four, it makes it difficult to generate a theory. The number of our cases, which is six, is therefore in line with the recommendations of the authors (Yin, 1994; Eisenhardt, 1989) who have worked on the subject and therefore pose no problem as regards the validity of the results.

As for the processing of the collected data, thematic content analysis was used (Paille and Mucchielli, 2012), as the data is discourse-based. Thus, each interview was fully transcribed in order to work on the original verbatim. We did the transcription of the interviews. After the transcription, the fragments of the texts of the interviews were grouped by sub-themes in a manual way.

THE MAJOR RESULTS AND THEIR INTERPRETATION

All the cases selected for this study are aware of the existence of the Central African Stock Exchange. Among the six cases surveyed, two have companies listed on the Central African Stock Exchange, that is, 33.33% of listed companies.

The results on the factors that block the listing of companies on the stock exchange and the measures to be adopted to stimulate the listing of

Cameroonian companies are presented below.

Highlighting the blocking factors for the listing of Cameroonian companies on the stock market

Several factors limit the listing of Cameroonian companies. Among these we find:

1) The willingness to manipulate financial reports to reduce the tax base;

2) Lack of information and awareness among companies;

3) Unpreparedness for an IPO;

4) The lack of a stock market culture;

5) The conditions of access to the stock exchange;

6) The lack of professionals;

7) The risks inherent in the stock market.

The concerns to reduce the amount of taxes to be paid

One of the reasons why Cameroonian companies

do not enter the stock exchange market is the fear of not being able to manipulate the financial accounts to pay the required amount of tax. Cases 1 and 6 are clear examples in this regard. Indeed, in Case 1:

"Most business managers or most bosses have got into the habit of manipulating the financial statements at the end of the year in order to produce the financial statements that suit them for the tax returns...

For Case 6:

"Many companies escape the state’s control on the payment of taxes at the required level. However, once on the stock exchange, these companies will be subject to the payment of real taxes. With the tax rate being very high, the taxation being very high, it hinders the companies”.

Two cases out of the six retained in our study are of this opinion, which is a rate of 33.33%. Thus, for the managers of these companies, the desire to reduce the amount of tax to be paid by cheating seems to prevail over the possibilities of long-term funding offered by the stock exchange.

The lack of information and awareness among companies, their unpreparedness, and the absence of a stock market culture

The results obtained indicate that Cameroonian companies, or rather their managers, are not sufficiently aware of the Stock Exchange or are not prepared to join it. This is evident from Cases 1, 2, 3, and 4 below. Indeed, according to Case 1:

"At the level of the stock exchange authorities, I think it is important to do some kind of media coverage. ... We are not prepared to go public.

For Case 2:

"Our Company is not listed on the stock exchange because we do not see the importance. It's true they say that the stock market allows you to have capital and all that..."

In Case 3: "We don't have enough information and enough communication".

In Case 4, it specifies that:

"... There is also a problem of education and awareness and publicity of the stock market ... Cameroonians do not yet understand the mechanisms of the financial markets ... SMEs do not yet understand the importance of a stock exchange».

Thus, four cases (66.66 %.) out of six mentioned the lack of information and awareness or unpreparedness as obstacles to the listing of Cameroonian companies on the stock exchange.

This lack of information and awareness or unpreparedness limits the knowledge that companies can have of the stock market and consequently their introduction to the said market. This is evident, as Cameroonian companies do not have a stock market culture, as the following statement by Case 4 attests:

"There is already the question of the stock market culture. Africans, especially in Central Africa, do not have this culture of the stock exchange market”.

This lack of information and awareness among Cameroonian companies, as well as the absence of a stock exchange market culture among these companies, prevent them from perceiving the chances they stand by entering the stock market. This situation therefore appears to be a handicap to the development of the stock market.

The access conditions to the stock exchange and the lack of professionals

According to some officials interviewed, the access conditions to the Central African Stock Exchange and the lack of professionals who can effectively manage the portfolio of companies are also obstacles to the listing of Cameroonian companies on the stock exchange. In this regard, Case 4 notes that:

"... The conditions of access to the stock exchange are also a barrier. They are not easy to comply with by medium-sized companies... We lack stock exchange professionals".

Even if Case 5 does not say so explicitly, indicating that:

"The stock exchange authorities should ... already go through the Higher Training Institutes and insert stock units in these institutions to train professionals", also highlights the lack of stock market professionals serving companies in Cameroon.

Two cases (that is 33.33%) out of six point to the access conditions to the stock exchange and the lack of professionals as limiting factors for Cameroonian companies to be listed on the stock exchange.

Risks inherent in the functioning of the stock exchange

Cameroonian companies are also afraid of the constraints inherent in the functioning of the stock exchange. Some managers think that going public would be a source of constraints for companies and could lead them to lose the management autonomy they have in their company. Thus, Case 2 highlights that:

“Already when you look at the climate in which we evolve, you look at the way things are regulated, the tax ... in fact we are afraid to go to the stock exchange market to eliminate ourselves. We are afraid of the constraints ... Going to the stock market, we risk a lot. Even our own management can be lost, you can completely disappear with the stock market, and you lose your management control and everything that goes with it”.

This fear would thus inhibit the willingness of Cameroonian companies, or rather their managers, to go public. Therefore, it is understood that several factors limit the access of Cameroonian companies to the stock exchange market, despite the funding problem they face, and so, it is important to take measures to encourage the managers of these companies to access the stock exchange.

Incentives for the listing of Cameroonian companies on the stock exchange

The company managers interviewed for the study proposed several measures to promote the access of Cameroonian companies to the stock market. Among these, we note:

1) Raising awareness among businesses;

2) Encouragement, support, and protection of companies by the public authorities;

3) The independence of the stock exchange from the public authorities.

Raising awareness among companies

Sensitisation is the most cited measure by the company managers interviewed for the study. Thus, Case 1 thinks that:

“At the level of the stock exchange authorities, I think it is important to do some kind of media coverage. We need meetings and symposiums to raise awareness among employers about the benefits. This sensitisation will focus on the credibility that the company could have once it is listed on the stock exchange. Its financial statements will be reliable, and sincere, reflecting the reality of the company's activities. Once on the stock exchange, the company will be able to do business easily with banks because it is a guarantee of financial security. The credits granted to it will be significant for a long period of time, which means that in the end all the stakeholders, investors, partners, and employees, will be satisfied and the company will be able to achieve its objectives and beyond the objectives, the results will be satisfactory”. These views are supported by Case 3, which notes that:

“Stock market managers must communicate much more ... If a company is sure that the stock market can solve its funding problems, since funding in Cameroon is a real problem, especially for medium-sized companies. We must go to the companies because we do not have the culture of the stock market. I think that the stock exchange must communicate much more”.

For Case 4:

“... We need to educate people about the financial market”.

Case 5 holds that:

“The stock exchange authorities should work together with companies to create awareness on the development of the financial market sector ... and then take measures to sensitize companies on the importance and missions of a stock exchange”.

Case six believes that the stock exchange:

“Must have a communication plan to raise awareness, to tell the public about the advantages of the stock exchange... Communicate the prices of assets live as it is the case in Wall Street so that it is seen in the world...”.

Five cases (83.33% of the cases) out of six recommend raising awareness among companies as an incentive to go public.

Encouragement, support, and protection of businesses by the public authorities

The results of the interviews conducted with our different cases reveal that the strengthening of the listing of Cameroonian companies on the stock exchange also requires certain measures from the public authorities towards companies. These measures include the encouragement, protection, and support of companies by the State of Cameroon. In this regard, Case 2 points out the following:

“What the state can do is to encourage us and see how it can protect us”.

As for Case 6, he thinks that the state should

“... Provide support to companies for their listing on the stock exchange. Thus, based on a diagnosis, a short list of companies that can be supported for the IPO can be established. Raise the company's awareness, grant facilities to the company”.

The statements of these two cases that constitute 33.33% of the total cases show that the State has an important role to play in improving the listing of Cameroonian companies.

Independence of the stock exchange from the public authorities

The independence of the stock exchange from the state is another factor that can favor the listing of Cameroonian companies on the stock exchange. Thus, for Case 6:

“The stock exchange must be independent. It must not be under the control of the state, although it is the regulator, it will not interfere in the circuit...”. This independence can dispel the fear of company managers toward the stock exchange. One case (16.66%) out of the six is of this opinion.

Interpretations of the main results

The results of the interviews conducted with our different cases have highlighted six groups of factors that limit the access of Cameroonian companies to the stock exchange. These include:

1) The willingness to manipulate financial statements to reduce the tax base;

2) The lack of information, sensitisation, and unpreparedness of companies;

3) The absence of a stock exchange market culture among companies;

4) The conditions of access to the stock exchange;

5) The lack of professionals to manage company portfolios; and

6) The risks inherent in the operation of the stock exchange.

The propensity to manipulate the accounting statements of Cameroonian firms had already been noted by some authors, including Ngantchou and Elle (2018) and Djeudja and Tedomzong (2017). In this regard, Ngantchou and Elle (2018) report that Cameroonian SMEs tend to cover taxable income. For these authors, if African companies manipulate their figures, it is primarily to minimize the tax base (Ngantchou and Elle, 2018). As for Djeudja and Tedomzong (2017), the manipulation of accounting data and tax evasion are circumvention strategies adopted by SMEs. The results also support those obtained by El M'Kaddem and El Bouhadi (2006) in Morocco. Indeed, these authors concluded that "Morocco does not have much experience in terms of transparency and financial disclosure. When new rules on mandatory financial disclosure were introduced as part of the reform of the Casablanca stock exchange, 18 out of 63 companies preferred to be delisted rather than expose themselves. Company accounts are a family secret that is not shared, especially with the tax authorities. Moreover, the opening of the capital is assimilated to the loss of control of the company (El M'Kaddem and El Bouhadi, 2006:20). This practice of reducing the tax base can be explained by the fact that companies do not sufficiently understand the importance of taxes in the functioning and development of a country. It justifies the reluctance to go public because stock market funding forces companies to be transparent and even disclose strategic information (Chemmanur et al., 2010; Fadil, 2016). This situation is a call on the public authorities to further explain the merits of taxation and to encourage companies to go public.

The lack of information and awareness of companies on the stock market identified in our study supports Avoutou’s (2018) conclusions. This situation can be explained by the absence of real information, education, and awareness programme for economic agents on the importance, advantages, and practices of the stock exchange market activity.

Indeed, in a stock market, the information and awareness of companies and investors play a very important role because they encourage the listing of companies on the stock market and make it possible to attract investors to the market, thus making it liquid. As such, the Canadian Securities Administrators (CSA) Investor Awareness Committee (IAC) places particular emphasis on relevant and up-to-date financial education through online campaigns designed to inform Canadians about investment trends, regulatory developments, and investor protection initiatives (Autorités Canadiennes en Valeurs Mobilières, 2021). Companies logically need to understand everything about how the stock exchange works the benefits of going public and the necessary protection, which can then dispel their fears and promote their listing.

For Avoutou (2018), the lack of stock market culture among companies in Africa, in general, is explained by the very young nature of the continent's financial markets, which have not yet been able to foster the development of a stock market culture in their environment. However, the stock exchange has existed in the Cameroonian business environment since 2001 which is 21 years today. This age corresponds to that of maturity. It seems to me that the lack of information and awareness of Cameroonian companies can also explain the weak stock market culture of these companies. This state of affairs should be of concern to the stock exchange authorities, one of whose missions is to inform investors, as well as the public authorities, because the stock exchange is at the heart of economic development.

For some Cameroonian business leaders, the access conditions to the stock exchange are not easy to meet, especially for Small and Medium-size Enterprises (SMEs). Indeed, on observation, it appears that the fundamental difference between Compartment A and Compartment B lies in the amounts of equity capital and minimum turnover. This leads one to believe that there has been no real adaptation of the conditions of access to the stock exchange to the environment.

In addition, the environment does not have a sufficient number of stock exchange professionals for better management of company portfolios. The lack of stock market professionals is not favourable to the listing of Cameroonian companies. This is what led some of the managers in our sample to recommend that training programmes for stock exchange professionals be developed in the higher training institutes. This result also raises the issue of the content of the market finance-teaching units given to management science students in Cameroonian universities. It also supports the view of El Aaroubi (2016:1) who reports that “getting listed on the stock exchange is a complex process that requires meticulous evaluation of alternatives, a lot of preparation by the board of directors and management, and a lot of advice from external specialists”.

Finally, the managers of Cameroonian companies are afraid of losing control of their companies by going public. This result can be explained by the family nature of most of the companies, which seek to preserve their financial autonomy and keep the company in the family fold. This result confirms those obtained by Schmidt (2008) who reports that the development logic of these companies is not compatible with that of the financial markets, which are mainly driven by speculation on mergers or break-ups, which generate rapid gains. It is also in line with that of Binder Hamlin (1994) who notes that joining a stock market is far from being an objective for family businesses, which are reluctant to be listed on the stock market in order to preserve their financial independence and therefore their economic and family assets. This result also reinforces those obtained by El M'Kaddem and El Bouhadi (2006) who reports that the decrease in the number of companies listed on the Casablanca Stock Exchange continued to increase after the second reform of 1997 and the introduction of electronic listing in 1998; the reason for this is the wave of mergers and acquisitions. In this context, and in a bid to promote the listing of companies on the stock exchange, the authorities must take measures to encourage, prepare, support, and protect companies, because going public cannot be improvised. These measures, coupled with a high level of awareness, can reassure companies and improve their listing.

CONCLUSION

The objective of this study is to identify the factors that prevent Cameroonian companies from seeking funding through the stock exchange market, despite their difficulties in financing their activities through bank loans. Thus, based on semi-directive interviews with six managers of public limited companies, several factors were found to limit the listing of Cameroonian companies on the stock market. These include:

1) The willingness to manipulate financial statements to reduce the tax base;

2) The lack of information and awareness or preparation of companies for going public;

3) The lack of a stock market culture among companies;

4) The access conditions to the stock exchange;

5) The lack of professionals to manage company portfolios; and

6) The risks inherent in the operation of the stock exchange.

By identifying these different factors that inhibit the willingness of companies to go public, this study contributes scientifically to the debate on the scope of the alternative offered by the stock market compared to the banking market. It also fills a gap by shedding light on the contrast between the need to finance investments and the lack of interest in the financial market, even though these companies are faced with insufficient financial resources. These results also suggest that the hierarchical funding theory and the behavioral model of timing and life cycle better explain firm funding in the Cameroonian context, since they pose the problem of the IPO from the perspective of the constraint.

At the managerial level, the results obtained constitute a challenge to the Cameroonian public authorities, stock exchange authorities, and business associations to implement vast information, education, and sensitisation programmes for business leaders on the importance, advantages, and practices of stock exchange activity. The adaptation of the conditions of access to the stock market to the reality of companies in the Central African sub-region, and the taking of accompanying and protective measures for companies should also be high on the list of actions to be carried out by public authorities, market authorities, and business associations. It should be remembered that the reproduction of the conditions of motivation and access of companies to the stock exchange imported from other environments very often does not give the expected results. The case of Morocco, which reproduced the European experience in the 2000s (Oudgou and Zeamari, 2018), which resulted in the failure of the third compartment dedicated to SMEs, is revealing in this respect.

However, this research has an inherent limitation due to the small size of the sample, which does not favor the generalization of the results. Despite this limitation, it was believe that this research has largely achieved its objective, as it was exploratory and was not intended to make generalizations. It has all the merit of having tackled a crucial problem for the development of enterprises and the economy, namely access to the financial market. Moreover, the above-mentioned limitation and the results obtained open up avenues for future research. Thus, future work can be carried out on larger samples in order to confirm or refute the conclusions of this study or better to test the impact of the perception that company managers have of the stock exchange on its development.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The author has not declared any conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

|

Abor J, Quartey P (2010). Issues in SME Development in Ghana and South Africa. International Research Journal of Finance and Economics 39:218-228. |

|

|

Autorités Canadiennes en Valeurs Mobilières (2021). La sensibilisation des investisseurs au Canada en 2021. Available at: |

|

|

Avoutou M (2018). Efficience des marches boursiers: qu'est-ce qui marginalise l'Afrique?. Revue Économie, Gestion et Société 18:1-20. |

|

|

Berger AN, Udell GF (1998). The economics of small business finance: the roles of private equity and debt markets in the financial growth cycle. Journal of Banking and Finance 22(6-8):613-673. |

|

|

BIT (2013). Évaluation de l'environnement des affaires au Cameroun, Organisation internationale du Travail, Génève. Available at: |

|

|

Bouazza A (2016). Les bourses des valeurs mobilières dans les économies en développement : Facteurs d'une émergence. Revue Marocaine de Recherche en Management et Marketing 2(14):244-270. |

|

|

Brian TG, Rutherford MW, Sharon O, Gardiner L (2005). An Empirical Investigation of the Growth Cycle Theory of Small Firm Financing. Journal of Small Business Management 43(4):382-392. |

|

|

Chang SJ (2004). Venture capital financing, strategic alliances, and the initial public offerings of Internet startups. Journal of Business Venturing 19(5):721-741. |

|

|

Chaouni S (2009). La performance des introductions en bourse: une étude sur les déterminants et des effets de la cotation sur les places de Paris. Thèse pour obtenir le grade de Docteur de l'Université des sciences et technologies de Lille Sciences Economiques. |

|

|

Chemmanur T, Yan A (2004). Product Market Advertising and Initial Public Offerings: Theory and Empirical Evidence. Working paper, Boston College. |

|

|

Chemmanur TJ, He J, Nandy DK (2010). The Going-Public Decision and the Product Market. The Review of Financial Studies 23(5):1855-1908. |

|

|

Daigne JF, Joly X (1986). Le second marché: un atout pour l'entreprise, Les Éditions d'Organisation, Paris. |

|

|

Demers E, Lewellen K (2003). The Marketing Role of IPOs: Evidence from Internet Stocks. Journal of Financial Economics 68(3):413-437. |

|

|

Djeudja R, Tedomzong AL (2017). L'impact de la pression fiscale sur le comportement financier des dirigeants des PME au Cameroun. Finance and Finance Internationale 6:1-23. |

|

|

Djoumessi F, Gonne J, Djoutsa Wamba L (2020). L'introduction en bourse améliore-t-elle la performance financière de l'entreprise ? Une application au cas des entreprises cotées à la douala stock exchange (DSX). Revue Congolaise de Gestion 1(29):101-133. |

|

|

Eisenhardt K (1989). Building Theories from Case Study Research. Academy of Management Review 14(4):532-550. |

|

|

El Aaroubi S (2016). L'impact de l'introduction en bourse sur la performance économique et financière des entreprises familiales au Maroc. Revue CREMA 4/2016:1-29. |

|

|

El M'Kaddem A, El Bouhadi A (2006). Les introductions à la Bourse de Casablanca : procédures, coût et causes de leur insuffisance. Critique économique 17:3-24. |

|

|

Eniola AA, Entebang H (2015). SME firm performance-financial innovation and challenges. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 195:334-342. |

|

|

Eshel I, Samuelson L, Shaked A (1998). Altruists, egoists and holligans in a local interaction model. American Economic Review 88(1):157-179. |

|

|

Essomba AC, Omengeule RG (2013). Le comportement des PME camerounaises dans une perspective d'émergence: un paradoxe. Revue Camerounaise d'Economie et de Management 2(1):73-91. |

|

|

Fadil N (2005). Introduction en Bourse, conduite stratégique et performance des moyennes entreprises françaises: une étude empirique. Revue Internationale PME 18(3-4):125-148. |

|

|

Fadil N (2016). Contribution de la cotation en Bourse à l'entrepreneuriat international. Revue de l'Entrepreneuriat 15(1):81-97. |

|

|

Fouda O (2009). La surliquidité des banques en zone franc: comment expliquer le paradoxe de la CEMAC?. Revue Africaine de l'Intégration 3(2):43-62. |

|

|

Giraud P (2001). Le commerce des promesses-Petit traité sur la finance moderne, Seuil, Paris. |

|

|

Goyeau D, Tarazi A (2006). La Bourse, La découverte, Paris. |

|

|

Hlady-Rispal M (2002). La méthode des cas - Application à la recherche en gestion, De Boeck Université, Bruxelles. |

|

|

Institut National de la Statistique (2018). Deuxième recensement général des entreprises en 2016 (RGE-2): Rapport principal, Yaoundé, Cameroun. Available at: |

|

|

Jacquillat B (1994). L'introduction en bourse, Deuxième édition, Presses Universitaires de France, Paris. |

|

|

Jemaa SB (2008). L'entreprise familiale tunisienne : structure financière et problèmes de financement. Cahier de recherche ERRCCI IAE Montesquieu - Bordeaux IV 29-2008. Available at: View |

|

|

Jensen MC (1998). Self Interest, Altruism, Incentives, and Agency, Foundations of Organizational Strategy, Mass, Harvard University Press, Cambridge. |

|

|

Jensen MC (2002). Corporate control and the politics of finance. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 4(2):13-34. |

|

|

Jillali SA, Belkasseh M (2022). Financial Performance of Initial Public Offerings: Exploratory study. Archives of Business Research 10(03):171-190. |

|

|

Jobard JP (1996). Gestion financière de l'entreprise, 11ème édition, Sirey, Paris. |

|

|

Korichi S, Mdaghri AA (2018). Entreprises familiales: de l'ombre vers la lumière (Cas des entreprises marocaines cotées). Revue Marocaine de la Prospective en Sciences de Gestion 1:1-24. |

|

|

Latham S, Braun MR (2010). To IPO or Not to IPO: Risks, Uncertainty and the Decision to Go Public. British Journal of Management 21(3):666-683. |

|

|

Lefilleur J (2009). Financer les PME dans un contexte de forte asymétrie d'information. Secteur privé et développement, le financement des PME en Afrique subsaharienne 1:14-16. |

|

|

Levasseur M et Quintart A (1998). L'entreprise et la Bourse, Economica, Paris. |

|

|

Luo JH, Liu H (2014). Family-concentrated ownership in Chinese PLCs: Does ownership concentration always enhance corporate value?. International Journal of Financial Studies 2(1):103-121. |

|

|

Mac an Bhaird C, Lucey B (2011). An empirical investigation of the financial growth lifecycle. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 18(4):715-731. |

|

|

Ministère des Petites et Moyennes Entreprises, de l'Economie Sociale et de l'Artisanat (2009). Étude sur la formulation du plan directeur (M/P) pour le développement des Petites et Moyennes Entreprises en République du Cameroun. Agence Japonaise de Coopération Internationale (JICA), Unico International Corporation. |

|

|

Modigliani F, Miller M (1963). Corporate income tax and the cost of capital: a correction. American Economic Review 53:433-443. |

|

|

Molou L, Ndjambou R, Fotso R (2018). Accès au crédit bancaire par le financement de proximité: Cas des PME Camerounaises. Management and Sciences Sociales 25:130-145. |

|

|

Myers SC, Majluf NS (1984). Corporate financing and investment decisions when firms have information that investors do not have. Journal of Financial Economics 13:187-221. |

|

|

Ngantchou A, Elle N (2018). La manipulation des chiffres comptables en contexte africain: la pertinence de l'hypothèse des «coûts politiques». In Transitions numériques et informations comptables. Available at: |

|

|

Oudgou M, Zeamari M (2018). L'apport Des Marchés De Capitaux Au Financement Des PME Marocaines. European Scientific Journal 14(7):350-372. |

|

|

Pagano M, Panetta F, Zingales L (1998). Why Do Compagnies Go Public? An empirical analysis. The Journal of Finance 53(1):27-64. |

|

|

Paille P, Mucchielli A (2012). L'analyse qualitative en sciences humaines et sociales, Éditions Armand Colin, Paris. |

|

|

Perrow C (1986). Complex Organisations, Random House, New York. |

|

|

Priolon J (2012). Les marchés financiers. Instituts des sciences et industries du vivant et de l'environnement, Agro Paris Tech, Paris. |

|

|

Reese W (2003). IPO Underpricing, Trading Volume, and Investor Interest. Working paper, Tulane University. |

|

|

Ross S (1977). The determination of financial structure: theIncentive Signaling approach. Bell Journal of Economics 8:23-40. |

|

|

Saada C (1996). L'entreprise et la Bourse. Cahiers français 27:73-80. |

|

|

Sassi H (2016). Impact de l'introduction en bourse sur la performance financière de la PME: cas de la société « Afric Indusdries ». Finance and Finance Internationale 5:1-14. |

|

|

Schmidt JB (2008). Bourse et financement des entreprises de croissance : le divorce ?. In: Glachant J, Lorenzi JH, Trainar P (eds.), Private equity et capitalisme français, La Documentation française, Paris. |

|

|

Schulz W, Lubatkin M, Dino R (2001). Agency relationships in family firms: theory and evidence. Organisation Science 12(2):99-116. |

|

|

Simon HA (1993). Altruism and economics. American Economic Review 83(2):156-161. |

|

|

Sraer D, Thesmar D (2007). Performance and behavior of family firms: Evidence from the French stock market. Journal of the European Economic Association 5(4):709-751. |

|

|

Stoughton N, Wong K, Zechner J (2001). IPOs and Product Quality. Journal of Business 74(3):145-176. |

|

|

St-Pierre J, Beaudoin R (1995). L'évolution de la structure de financement après un premier appel public à l'épargne: une étude descriptive. Revue Internationale PME 8(3-4):181-203. |

|

|

Szpiro D (1998). Informations et vitesse de réaction du marché boursier en continu : Une analyse empirique du marché boursier français. Revue Economique 49(2):487-526. |

|

|

Tchapga Djeukui CC (2021). Profil du dirigeant et introduction en Bourse au Cameroun : Lectures théoriques et enjeux pratiques. Journal of Academic Finance 12(1):80-99. |

|

|

The World Bank (2008). Doing Business 2009. Comparaison des règlementations dans 183 pays. |

|

|

The World Bank (2009). Doing business 2010: Reforming through difficult times. |

|

|

Wanda R (2007). Risques, comportements bancaires et déterminants de la surliquidité. Revue des Sciences de Gestion 6(228):93-102. |

|

|

Yin RK (1994). Case study research: Design and methods, 2nd Edition, Michigan: Sage publications. |

|

Copyright © 2024 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article.

This article is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0