Full Length Research Paper

ABSTRACT

The study seeks to assess the effect of privatisation on political and managerial accountability, considering the cases of Intercity State Transport Company and GAFCO. A sample data were collected from both managerial staff and some junior employees through interviews and questionnaire. Paired sample test was used to analyse the data of the questionnaire and content analysis for the interviews. The results indicated that privatisation decreases political accountability and increases managerial accountability. It was recommended that privatisation transaction should encourage a wide share ownership; widely disposed ownership makes the companies less vulnerable to cash traps. Also shareholders should invest in companies introducing training programmes for staff to improve their skills. The shareholders should be interested in the efficiency, effectiveness and maximum performance of the companies.

Key words: Accountability, privatization, effects.

INTRODUCTION

Privatization accelerated in the 1990s. In Europe, this was sparked by the liberalisation of markets at the European Union level and budgetary constraints faced by governments (Parker, 1999). Privatisation particularly gained momentum in the late 1980s and spread to a wide range of developing economies. The success stories of privatisation in Europe and other parts of the world made countries in Africa, particularly Ghana, to have a second look at its state- owned enterprises. Ghana’s State Owned Enterprises (SOEs) came to prominence shortly after independence in 1957. This was because they were viewed as crucial and necessary instruments in the drive towards industrialization. By the mid-eighties, the Government of Ghana was thus engaged in all sectors of the economy (Kubi, 2001).

Contrary to expectations, however, most SOEs were not able to accomplish the purpose for which they were established. They were characterized by poor management and low performance, over stretched bureaucracies, conflicting and poorly defined social and commercial objectives, poor incentives, abuse of monopoly power, corruption and political interference, and indebtedness (Sakyi, 2009). To arrest the situation, government after government set up probes or commissions and committees of inquiry to investigate the causes for the poor performance of these enterprises and to recommend remedial measures for their improvement. One of the prescriptions for the Economic Recovery Programme was that, the state had no business in doing business and should therefore reduce the size of its activities by privatizing some of the SOEs as to avoid the waste of resources and to channel resources to more fruitful and productive ventures (Boachie-Danquah, 1990). This presupposes that completely privatised enterprises have no business with the government. Thus their accountability should be towards management instead of government. This is the case with privatised enterprises.

Privatising public enterprises will lead to improved accountability and performance (Sakyi, 2009). Some privatized enterprises in Ghana have or are at the verge of folding up as a result of poor financial and managerial controls. What accounts for this? It is in this direction that the study seeks to assess the accountability processes before and after privatisation in both Intercity STC Coaches Limited and Ghana Agro Food Company Limited (GAFCO).

The objective of the study is to: Identify the structures of accountability before and after privatisation in GAFCO and Intercity STC and to assess the effects of privatisation on political and managerial accountability in privatised enterprises. The research questions are; what structures of accountability existed in these companies before privatization? Has there been a change in these structures after privatization? What are the effects of privatisation on political and managerial accountability?

The study therefore hypothesizes that:

HI: Privatisation increases managerial accountability.

H2: Privatisation decreases political accountability.

RELATED LITERATURE

Accountability will be defined as ‘setting goals, providing and reporting on results that are the visible consequences for getting things right or wrong, including rewards or sanctions as appropriate” (Funnell and Cooper, 1998). Central to the discussion on accountability has been a distinction between ‘managerial’ and political/public forms of accountability. The latter is assumed to apply particularly to governments who are accountable to their electors for the authority granted to them whereas the former applies to managers being made accountable for the responsibilities delegated to them by their owners. In the case of government it is assumed that the direct control of the electorate is limited on the other hand in the context of managerial form of accountability, it is assumed that the person who delegates responsibility can and have power to exert pressure over the performance of the later (Ahrens, 1996).

Political accountability is implied to be more open-ended and less detailed whilst managerial accountability is more closed and defined. This distinction is important since it, in effect, recognises that there are limitations on the controlling power of the principal’. Adopting and accepting political forms of accountability is an acknowledgment of limited power over the ‘agents’: political forms of accountability are relevant in the management of public enterprises. This is because governments will formally be called to account to the electorate for their activities and allow them to decide, through the ballot box, on continuation or cessation of office. On the other hand, managerial accountability is intentionally more proactive with an underlying desire to ensure ‘agent’ behaviour is in compliant both in the long and short term. This is recognised not to be possible with governments but to the private sector (Broadbent and Laughlin, 2001).

There can be different levels of both political and managerial forms of accountability. Stewart’s ladder of accountability provides a useful illustration of these different levels. The rungs of his ladder start with accounting for probity and legality which reports that funds have been used in an appropriate manner. ‘Appropriate’, in this sense, is related to legally acceptable pursuits defined by the principal. The next level is process accountability which accounts for details of the actions processes followed by the agent. The next two levels are performance accountability and programme accountability which together is intended to provide an account of the total work performance of the agent in terms of specific goals set by the principal. These three rungs are normally associated with Broadbent and Laughlin (2001) control and legitimating in government accountability process: the private initiative in the U.K managerial form of accountability (Stewart 1984 as cited in Broadbent and Laughlin, 2001).

According to Coleman (1990), the different level of accountability in Stewart’s ladder is not needed since there is a high level of trust that the agent will comply with what the principal requires.

Similarly, Wouters et al. (2010) stated that managerial accountability increases in privatised enterprises as compared to the public. They added that managerial accountability may be put in practice in a variety of ways and through a variety of channels and through a variety of means (mechanism). One of such channel is legal accountability; the implementation of this channel of accountability is that, the actions of the agent being called to account fall within the scope of an applicable law, and that the said agent may face consequences as a result of the application of such law. Disciplinary accountability is the second channel of managerial accountability and it consists of the internal administrative procedures of the organization through which the actions of employee can be judged and sanctioned. Furthermore, the staff regulations define disciplinary proceedings and penalties. The third on the list is mediatory accountability which constitutes an alternative accountability channel which is not characterised by a judgement scheme, but rather by a dialogue between the organization and the public. This channel aims at analysing the reasons of a possible dysfunction and to reach an agreeable and constructive solution for each party involved. Mediatory accountability processes are typically embodied by an ad hoc person/ institution called an ombudsman.

Stewarts (1984) and Wouter et al. (2010) all talked about mechanisms of accountability. They gave legal, performance, process and structure of an organization whistle blowing etc as mechanisms for ensuring accountability.

Romzek and Dubnick (1997) also propose four perspective mechanism of public accountability; legal, political, hierarchical and professional. They explained legal accountability as on obligatory relationship with the individual or group that imposes legal sanctions or contractual responsibility. Legal requirements produce this accountability relationship, and it is driven by external organizations, mainly from the legislatives and the courts. They also explained hierarchical accountability as holding public servants accountable to hierarchical supervisors, directives, organizational standard operating procedures and rules. These relationships are restricted within an organization and the degree of control is high. Professional accountability relationships emphasize “the exercise of discretion on the part of the employee in a manner that is consistent with internalized standards of performance, typically those of one’s profession or peer work group. In this accountability relationship, public administrators are held accountable to peer professional culture and norms. Political accountability mechanism refers to political responsiveness. A public agency has to be accountable to external groups’ expectations. In particular, the citizenry is the basis of legitimacy and they delegate their power to public officials to design and implement public policies according to citizens’ preferences and expectations. Steffek and Kristina (2008) seem to agree on legal, hierarchical, professional public electoral as mechanisms of ensuring political accountability.

The distinction of political and managerial accountability discussed above are essential to the study in that it will be to use as indicators to test the hypotheses stated earlier.

Theoretical position of the study

Babbie (2004) defined theory as a set of interrelated statements intended to explain some aspect of social life. So in examining the concept of privatisation and accountability the property rights theory and the agency theory are reviewed here as forming the theoretical foundations of privatization and accountability. The Property rights theories, articulated by Alchian (1977) and Demsetz et al. (1988) suggest an explanation for privatization. In their view, the shareholder is the residual claimant to profits in publicly traded firms, whereas under state ownership, property rights are ill defined. Although the state is the residual claimant to any profits in a state-owned firm, the minister (as the state's representative) has no financial interest in the returns stemming from his actions (or inaction). Moreover, there is unlikely to be a personal gain to the minister. Among the activities in the minister's portfolio of responsibilities, monitoring State-Owned Enterprises is likely to be relatively invisible to the electorate. So long as there is no personal gain and some personal cost in designing or managing an effective governance system, state representatives will neither work hard at monitoring managers nor design governance systems to enhance efficiency. To exacerbate this problem, managers of State-Owned Enterprises are insulated from the threat of takeover and bankruptcy common to privately owned firms.

Property rights theories predict that privatization will enhance incentives tied to firm financial performance by replacing disinterested ministers with shareholders who will design an effective governance system out of self-interest. To the degree that privatization limits effective corporate governance; such theories predict fewer incentives in privatized firms relative to established publicly traded firms not subject to these constraints. In particular, the corporate governance literature suggests that the strength of incentives will depend on how privatization affects ownership concentration, the ease of transfer of ownership, and the level of financial freedom granted to management.

The property right theory asserts that managers strive towards cost minimization if their rewards are directly linked to economic performance. In other words, if workers and managers expect big bonuses when their company posts impressive profits, then they would strive to minimize costs in order to get hold of the fat bonuses. This profit maximization drive results in maximization also of the value of property rights. They argue that private ownership is more likely to achieve this since there is a direct link between ownership and management control, and thus there is someone in charge, unlike the situation with public enterprises where the incentive to do this is not very much.

The agency theory on the other hand can be viewed from the point of principal agent theory. In the principal agent model, the principal is the owners of the capital assets over which the agent has day-to-day control and manages normally on behalf of the principal. However, the agent typically has different interest to that of the principal and may, for example want an easier life and a higher salary than is consistent with maximizing the welfare of the principal via the return which the principal receives from his (or her) investment in the capital assets that the agent is managing nominally on the principal’s behalf. In order to control the agent, it is in the interests of the principal to incur monitoring cost of obtaining and processing information about the performance of the agent and the extent of his (or her) conformity with the principal’s own objectives. In addition, it may also be in the interests of the agent to incur bonding cost to convince the principal that the agent is worthy of his or her hire. The outcome of the principal agent relationship will not, however, be the maximization of the principal’s welfare since not only the cost of monitoring and bonding be significantly positive, but also, particularly in the presence of a strong divergence of interest between the agent and the principal, the monitoring and bonding processes may themselves prove to be imperfect forms of controlling the actions of the agent. The result of the principal-agent relationship will then be not the positive monitoring and bonding costs but also a remaining residual loss, resulting from a “divergence between the agent’s decisions and those which would maximize the welfare of the principal (Jensen and Meckling 1976).

Increased accountability means that the principal should incur additional expenditure on monitoring and bonding cost in order to obtain and process more information about the activities of the agent in managing the asset of the principal. In the public enterprise because the state (principal) has no direct interest in the enterprise, this monitoring and bonding cost is normally not taken seriously. But in the private sector because the principal are the stakeholders (owners of the enterprise) they have direct interest in the business and are prepared to pay monitoring and bonding cost to ensure that the agent is held accountable. So accountability according to the principal-agent model is increased in the private sector than the public sector.

These theories are useful to these studies because the Property Right Theories gives an explanation and justification for privatising State Own Enterprises, whereas the Agency Theory also explains why account-tability is effective in the private enterprises. With private enterprise, shareholders are prepared to pay bonding and monitoring cost to ensure that managers are accountable for their actions. But in the State Own Enterprise there is not such commitment. These theories will be useful for my study because it will be used as a yardstick to measure whether the government was right in privatising these companies and if they have achieved their aim in privatising them. The Agency Theory will also be used to compare accountability mechanisms before and after privatisation. If really accountability is improved when enterprises are privatised.

METHOD

The study uses two firms (Intercity State Transport Coaches Limited (STC) and Ghana Agro Food Company) as the case study to explore whether privatization has, indeed, improved or worsened these companies. In this study the population consisted of members of managerial ranks and staff ranks of Intercity STC and GAFCO in Accra and Tema respectively. In all, 200 management and non-management employees were targeted for the study. According to Sekaran (2000), the ideal sample size for this population size should consist of approximately 108 respondents. Of the 200 employees targeted in both enterprises, only 77 filled and returned their questionnaires, 48 from Intercity STC and 29 from GAFCO. The response rate for the study was a little over seventy-one per cent (71.29%).

Questionnaires were used for the survey while interviewer guides were used for the key informant interviews. A tape recorder was also used in recording the interviews.

The study uses both qualitative and quantitative analyses. The quantitative analysis is useful in determining to what extent privatisation affects public accountability. This study collected data through a survey. The target samples covered were staff of both Intercity STC and GAFCO, questionnaires were sent to these organizations.

According to Babbie (2004) sampling is to select a set of elements from a population in such a way that descriptions of those elements accurately portray the total population from which the elements are selected. Those who constituted the sample population of this study were management and non-management ranks from Intercity STC in Accra and Ghana Agro Food Company in Tema.

A stratified sampling method was adopted for questionnaire administration. This means management and non-management employee of different ages and performing different professional roles within the enterprises were targeted. The list of employees in the two organizations was requested for this method. Intercity STC had 550 employees and that of GAFCO was also 450 making 1000 employees in all. The 1000 employees with their names which constitute the population of the study were divided into 100 sub population (strata). After dividing the population into strata, the researcher drew a random sample from each sub population (strata). The researcher began with a random start of 2 (two) and every tenth person thereafter was selected. Ten employees were selected from each stratum until the sample size of 200.

A stratified sampling was considered useful for this study because accountability is an issue for all members in the organisation. Since individual members of the organisation interact at cross level of the organisation and are made up of different professional groups, age groups and gender groups, it was important to reach out to all of them.

In addition to the above, the purposive technique was used for the selection of the officers for interview. This is because the questions asked were technical and needed people with in depth knowledge on accountability in their organization.

Eight interviews were conducted with top management from the two enterprises. The questionnaire contained questions on accountability before and after privatisation. The questions were meant to be answered by both management and non-management of the two case studies. Section A asked questions on the structure and levels of accountability before and after privatisation, section B also enlisted from respondents the mechanisms of privatisation before and after privatisation. Section C also posed questions on institutions that the enterprises are accountable to.

The Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS) was used for all statistical calculation. This assisted in describing the data more succinctly and to make inferences about the characteristics of population on the basis of data from sample.

The Paired sample t-test is a statistical technique that is used to compare two population means in the case of two samples that are correlated. Paired sample t-test is used in ‘before-after’ studies, or when the samples are matched pairs, or the case is a control study (Aspelmeier and Pierce, 2009). In this study, the researcher was interested in assessing accountability mechanisms and structures before and after privatisation. Paired sample t- test was selected to know the effect of privatisation on political and managerial accountability. The following steps were followed in conducting the test:

1. Set up hypothesis: We set up two hypotheses. The first is null hypothesis, which assumes that the mean of two paired samples are equal. The second hypothesis will be an alternative hypothesis, which assumes that the means of two paired samples are not equal.

2. Select the level of significance: After making the hypothesis, we choose the level of significance. In most of the cases, significance level is 5%, used by most social science researchers.

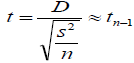

3. Test statistics is given as calculated parameter: To calculate the parameter, the following formula was used:

Degree of freedom under the null hypothesis

Degree of freedom under the null hypothesis

Where D bar is the mean difference between two samples, s² is the sample variance, n is the sample size and t is a paired sample t-test with n-1 degrees of freedom.

By using t-distribution table to compare, the value for t, to the tn−1 distribution, will give the p-value for the paired t-test.

4. Testing of hypothesis or decision making: After calculating the parameter, the researcher compared the calculated value with the table value. If the calculated value is greater than the table value, then we will reject the null hypothesis for the paired sample t-test. If the calculated value is less than the table value, then the null hypothesis is accepted and concludes there is no significant mean difference between the two paired samples. A convenient way of comparing is the use of p-value. In this regard, if the p-value is less than the alpha level in this case 0.05 is used, we reject the null hypothesis otherwise accept the null hypothesis. Having taken decision in the above, it is concluded in non-statistical term.

RESULTS

Interviews

Eight managers, four each from GAFCO and Intercity STC were interviewed. At intercity STC the government went into a public private partnership (PPP) with Social Security and National Insurance Trust (SSNIT). According to all four of the respondents (100%) the structure of accountability before the involvement of the private partners was direct from bottom to top of the organizational structure. All four respondents (100%) also asserted that the accountability mechanism before privatization was weak. According to the director of finance and administration, because the employees had worked together for at least ten years or more, accountability in the company suffered through personal trust and friendship neglecting documented proofs. This situation therefore made the accountability structure less effective and almost non-functional. Also, the director of operations was firm that there was no proper supervision of work, ruining the accountability mechanisms in the organization. This was affirmed by the Head of engineering, who showed much concern on the procurement procedures in the organization. Although the company’s policy was to adhere to the Ghana Public Procurement Act, 2003 (ACT 663), he believed there was less compliance, which was a breach to the company’s accountability mechanisms. All respondents (100%) admitted there had been drastic changes to the structure and accountability mechanisms after privatization. The re-structuring had made the process more complex but effective.

Likewise in GAFCO, the government went into a Public Private Partnership with Industrie Bau Nord (I.B.N) and SNNIT. All (100%) respondents were clear in their assertion that there had been a complete overhaul of the accountability structures and mechanisms in the company. A majority of the respondents (100%) expressed complete satisfaction of the new accountability mechanisms and absolute dissatisfaction in the old structure and its mechanisms.

Hypotheses testing

The purpose of this section is to evaluate the hypotheses stated earlier in chapter one and, four. The hypotheses are:

Ho1: Privatisation does not increase managerial accountability.

H1: Privatisation increases managerial accountability.

Table 1 shows a Paired Samples Statistics between managerial Accountability before Privatization (mean = 9.06, N = 77, SD = 3.16) and managerial Accountability after Privatization (mean = 12.3, N = 77, STD = 4.703)

The result is significant (77) = -7.53, p = 0.000. We reject the null hypotheses in favour of the alternative; therefore the result is statically significant. That is managerial accountability before and after privatization are not the same. Using the mean score of accountability before privatization (mean = 9.06) and mean score of accountability after privatization (mean=12.34) we have found strong evidence that privatisation increases managerial accountability since the average score after accountability is greater than average before (Table 2).

Ho2: Privatisation does not decrease political accountability.

H2: Privatisation decreases political accountability.

Table 3 shows a Paired Samples Statistics between Political Accountability before Privatization (mean = 12.84, N = 77, SD = 4.92) and Political Accountability after Privatization (mean = 8.53, N = 77, STD = 3.13).

A paired samples t-test was again carried out between score on political accountability before and after privatization and political accountability before and after privatization (Table 4). The test reveals that there was a highly statistical difference between score political accountability before and after privatization t (77)) = 8.99, p < 0.05. The mean score on Political Accountability before Privatization (mean = 12.84, N = 77, SD = 5.01) was higher than the mean scores on Political Accountability after Privatization (mean = 8.53 N = 77, STD = 3.13). Hence, we can conclude with a high level of confidence that privatization policy has a significant effect on political accountability, and that Privatization decreases political accountability.

The result of the hypothesis is consistent with (Mo (2000) and Hodge and Coghil 2007) in their study where they all concluded that privatisation decreases political accountability and increases managerial accountability.

DISCUSSION

The results from the key informant interviews from the two cases studied revealed that the mechanism for accountability before privatisation was consistent with simple/ministerial traditional form of accountability. According to Hughes (1994) in public enterprise, the public servants ensured that ministerial policies are carried out in an effective and efficient manner when using public resources. In other words, in the ministerial model, it relies on the availability and application of the necessary resources for the exercise of power. This is seen in all the accountability mechanisms in both enter-prises before privatisation. The aim of these mechanisms was not to lead to high productivity but to satisfy the public and keep government and its officials in power.

On the other hand, accountability mechanism after privatisation is broadly consistent with the complex model of accountability found in the United Kingdom by Scott (2000). According to Scott, with the complex account-ability model the privatised state is accountable to a number of actors and power is dispersed. The result from the key informant interviews is therefore consistent with the findings of Scott (2000).

The interviews also revealed that, the poor account-ability mechanisms and ineffective compliance affected customer care. After privatization however, interviewees at intercity STC revealed that frontline employees have been trained to relate well with customers. This supports Hood (1995)’s argument that consumer sovereignty is better served under privatised enterprises.

Furthermore, publishing financial statement was not a priority of both companies since none of the interviewees mentioned it. However at GAFCO, observation showed that it had once been published in their newsletter. This situation also supported Habermas (1996), who stated that the publishing of financial statement and auditing may be done on the request of stakeholders.

Another observation that was made was the consistent mentioning of regulatory institutions as a mechanism of ensuring accountability in both case studies. In both case studies, we saw licence revocation, licence suspension, warning letters and persuasions, and closure of factories by regulatory institutions to ensure compliance. These are consistent with Ayres and Braithwaite (1992)’s studies on regulatory enforcement.

Survey

Again the findings from the research survey are not substantially different from the literature. Despite some few differences, most of the issues raised are very much similar to those found in the literature.

According to Luke (2010), Wouters (2010) and Hodge and Coghil (2007) privatisation brings about clearly defined reporting lines and improved supervision. The responses from the respondents on the question on reporting systems showed that when organizations are privatised, there are clearly defined lines of authority and reporting systems as well as improved supervision as indicated in the literature.

On the issue of consultation with shareholders in decision making, the study showed that consultation with shareholders is better achieved when organisations are privatised. This makes the shareholders monitor and control both management and non- management ranks (agent) as stated in the Agency Theory. The response also confirms Borren (1995)’s accountability model which states that when enterprises are privatised, stake holders are able to monitor and supervise management to ensure that their interests are protected.

Lastly, under the structure of accountability, the respondents revealed that consumers are able to seek redress to their problems in privatised enterprises through the use of Complaint Unit as compared to the public. This is similar to Cook and Kirkpatrick (1995)’s studies. They also argued that privatised enterprises have Complaint Unit where employees and customers can report wrong doings or problems. However in Mo (2000) he revealed that the complaint unit and suggestions box used by the public to address their problems are not adhered to in the private enterprise as compared to the public.

Also, all the mechanisms of accountability identified by respondents during the research process had been noted in other literature on the issue of privatised enterprises operating within the laws of the state. The study showed that whilst before privatisation the enterprises operated according to the laws of the land, after privatisation the enterprises operated according to the rules and regulations of the enterprise instead of the laws of the state. This confirms Habermas (1996) claims that privatised enterprises are normally bound by organizational rules and regulations rather than the state laws. He argued that the state laws cannot obligate private enterprises to publish their financial statements. He reiterated that it can only be done on the request of shareholders. He said that the state (government) can only enforce compliance to state laws only if it is the majority shareholder in the privatised enterprises.

Again, in responding to the issue on transparency, the study revealed that when it comes to access to information and auditing it is better served under the public enterprises than the private. This is similar to Kettle (1993)’s studies on privatisation and accountability. He argued that privatisation has impacted negatively on accountability in terms of transparency and public criticisms. However, Bishop Kay and Mayer (1994) had a different view. They think privatisation increases transparency. Even though the findings are similar to kettle, it is different from Bishop Kay and Mayer’s view.

Furthermore, Therkildsen (2001) argued that performance targets can be used as a mechanism for accountability. He stated that performance targets are used as measuring scale to judge if accountability exists in an organization, since when management set targets there is a need to communicate it to non- management rank so they can work together as a team. This makes them accountable to each other. According to Therkildsen setting performance targets are practiced by private enterprises rather than the public. The response from the respondents confirms this.

Also, respondents agreed that regulatory institutions are mechanisms for ensuring accountability in privatised enterprise. This confirms the study of Hodge and Coghil (2007) and Ayres and Braithwaite (1992). In their discussions they stated that if all mechanisms fail to hold privatised enterprises accountable, the only mechanism that can be use is regulatory enforcement by regulatory bodies.

Additionally, whistle blowing schemes were also identified as a mechanism for ensuring accountability. The study revealed that the private sector has procedures through which employees can report wrong doings without being victimised as compared to the public.

This is consistent with Wouters et al. (2010)’s arguments which stated that for accountability to be sustained there must be whistle blowing schemes in which employees have the right and sometimes the obligation, to report cases of misconduct of which they may become aware of.

Lastly, findings from the survey also revealed that privatised enterprises are accountable to a number of stake holders that is owners, suppliers, customers, the public, etc.

From the findings of the interviews and questionnaires, it can be established that the theories chosen for the study are very much in line with the study; The Property Right Theory by Alchian (1977), Demsetz (1988) and Agency Theory by Meckling (1976). As stated earlier, according to the Property Rights Theory, shareholders are residual claimant to profit in public traded firms, whereas under state ownership, Property Rights are ill defined. Although the state is the residual claimant to any profits in a state-owned firm, the minister (as the state representative) has no financial interest in the returns stemming from his actions (or in actions). The theory also predicts that privatisation will enhance incentives tied to the firms, financial performance by replacing disinterested ministers with shareholders who will design an effective governance system out of self-interest. The findings show that because shareholders know they have an interest in the company, the number of mechanisms has been increased to ensure accountability which will be translated into high production and increase the profit of shareholders. Again, after privatisation the disinterested ministers heading the various State-Owned Enterprises were replaced with the shareholders.

The Agency Theory by Meckling (1976) was reviewed from the point of the Principal and Agent Theory, where the principal is the owner and the agent is the one who manages the day-to-day control of the enterprise on behalf of the principal. The principal also incurs monitoring and bonding cost so as to ensure they are accountable. From the study, it can be seen that owners of the company have put in place measures and mechanisms to ensure that managers operate according to laid down procedures. All the mechanisms have been put in place to control management and non-management ranks (agents). The theories are therefore consistent with study.

CONCLUSION

This chapter discussed the findings of the individual interviews, the survey and also tested the hypotheses. From the individual interviews, it was realized that accountability mechanism before privatisation was narrow and directed towards government and its institutions. But after privatisation the mechanisms were widened and the enterprise became accountable to a number of people or actors. The hypotheses also confirmed the literature that political accountability decreases as state owned enterprises are privatised and managerial accountability increases.

The study focused on two privatised enterprises in the Accra and Tema Metropolis both in the Greater Accra Region of Ghana. The researcher sought to find answers to the following questions on the structure and levels of accountability before and after privatisation; mechanisms of accountability dimensions and the effect of private-sation on political and managerial accountability. Results from the study indicate that; privatisation has reduced government’s direct control over privatised enterprises.

The study also revealed that privatised enterprises are accountable to a larger number of stake holders i.e. shareholders, supplier, customers and the public. The hypothesis tested also revealed that privatisation has an impact on both political and managerial accountability. Privatisation reduces political accountability and increases managerial accountability. The Agency Theory and Property Right Theory were used as the basis of the analysis. And the findings were seen to be consistent with the theories selected for the study that is the Property Right Theory and the Agency Theory.

It has extensively been acknowledged in the literature that privatisation brings about improved accountability and performance (Hodge and Coghil 2007; Luke 2010, Wouters et al 2010). As a result of this, most ailing State Own Enterprises were privatised to improve on their accountability leading to improved performance. The study of these two privatised enterprises, that is Intercity STC and GAFCO have revealed privatisation indeed leads to improved accountability but not performance.

Findings from the study also showed a reduction in the role of government in privatised enterprise. The hypotheses tested showed a decrease in political accountability after privatisation and an increase in managerial accountability. There is a need for further research on challenges of privatised enterprises. These studies should also come up with reasons why privatised enterprises are collapsing despite improved accountability mechanisms. Also, there is a need for further research on GAFCO and Intercity STC to find out why they are not performing even after privatisation.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The author has not declared any conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

|

Ahrens J (1996). 'Style of Accountability' Accounting, Organization and Society, J. Account. Auditing Accountability, 21:139-173. |

|

|

|

|

|

Alchian A (1977). "Some Economics of Property Rights", London: George Yarrow. |

|

|

|

|

|

Appiah-Kubi K (2001). "State-owned enterprises and privatisation in Ghana" J. Modern Afri. Stud. 39 (2):197-229. |

|

|

|

|

|

Aspelmeier JE, Pierce T (2009). SPSS a user- Friendly Approach, New York: Catherine Wood. |

|

|

|

|

|

Ayee RA (1991). "Civil Service Reforms under the Provisional National Defence Council (P.N.D.C) of Ghana",J. Manage. Stud. 7:1-12. |

|

|

|

|

|

Ayres I, Braithwaite J (1992). Responsive Regulation, New York; Oxford University Press. |

|

|

|

|

|

Babbie E (2004). The Practice of social research, Texas: Wadsworth Publishing Company Pp. 101. |

|

|

|

|

|

Baffoe W (2010). Personal Interview, 18th November 2010, State Enterprises Commission, Chief of administration |

|

|

|

|

|

Bishop KMJ, Mayer C (1994). Privatisation and Economic Performance, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. |

|

|

|

|

|

Boachie-Danquah, N (1990). "Structural Adjustment, Divestiture and the Future of State –Owned Enterprises in Ghana", J. Manage. Stud. 6:83-91. |

|

|

|

|

|

Boachie-Danquah N (2000). "Privatization, Globalization and Exports: Some Experiences from Ghana", J. Managt. Stud. 15(1):82. |

|

|

|

|

|

Borren AJ (1995). The Intangibles of Managing, Palmorston North: Dunmore Press. |

|

|

|

|

|

Broadbent J, Laughlin R (2000). 'The Private Finance Initiatives in the U.K: Contracting in the Concept of Infrastructure Invest Control, Accounting, Auditing and management. 7(4): 259-284. |

|

|

|

|

|

Broadbent J, Laughlin R (2001). Control and Legitimation in Government Accountability Processes: The Private Finance Initiative in the U.K. Critical Perspective on Accounting, 7(4):1-30. |

|

|

|

|

|

Coghill FS (2000). 'Complex Governance: Ministers, Responsibility and Accountability", Paper Presentation at the Privatisation and Good Governance Conference, Melbourne, September 8, Coleman J (1990). Foundation of Social Theory, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Collective Agreement: Ghana Agro Food Company limited and the industrial and commercial workers union (ICU) Ghana. 20: 22. |

|

|

|

|

|

Cook P, Kirkpatrick C (Eds) (1995). Privatisation policy and performance: International perspective, Prentice-Hall: Engle wood cliffs, NJ. |

|

|

|

|

|

Demsetz H (1988). "The theory of the Firm Revisited", J. law Eco. Organization. 4(1):141-161 |

|

|

|

|

|

Funnel W, Cooper K (1998). Public Sector Accounting and Accountability in Australia, Sydney: UNSW Press. |

|

|

|

|

|

Habermas J (1996). Judiciary and Legislative: on the role and legitimacy of constitutional Adjudication, Cambridge: MIT Press. |

|

|

|

|

|

Hansen JJ (2003). Limits of competition: Accountability in government contracting, J. the Yale Law, 112: 8. |

|

|

|

|

|

Hodge GA, Coghill K (2007). Accountability in Privatized State, An international J. Policy, Administration, and institutions, Pp.20, Hood C (1995). Contemporary Public Management: A New Global Paradigm?, Public Policy and Administration 10(2):104-117. |

|

|

|

|

|

Hughes O (1994). Public Management and Administration: An Introduction, New York: St Martins Press. |

|

|

|

|

|

Jensen M, Meckling W (1976). "Theory of the Firm: Management Behaviour, Agency. Cost and Ownership Structures", J. Financial Eco. 3:77. |

|

|

|

|

|

Kettle DF (1993). "Sharing Power: Public Governance and Private Markets," Washington DC: The Brookings Institutions, www.allacademic.com Access on 20th January, 2011. |

|

|

|

|

|

Kettle DF (1993). The Myths, Realities and challenges of Privatization, California: (www.allacademic.com), access on 20th January, 2011. Pp.246-275. |

|

|

|

|

|

Luke B (2010). Examining Accountability Dimension in State-owned Enterprises, Finan. Account. Manage. 26(2): 134-162. |

|

|

|

|

|

Mo C (2000). Civil servants perception of citizens and its impacts on citizen Participation "a paper preserved at the ASPA conference," San Diego, CA. pp. 1-5. |

|

|

|

|

|

Mo C (2000). Privatisation and Public Accountability Comparison between Private and Public Bus Operation (PHD Dissertation), Jacksons State: Jacksons State University, http://www.jsum.edu/jsublme. Access 14th December, 2010 |

|

|

|

|

|

Nesslein TS (2008). Enterprise Public vrs Private in Evan M. B, (Ed), Encyclopaedia of Public Administration and Public Policy-2nd ed. –New York, Taylor and Francis Pp. 661-663. |

|

|

|

|

|

Nkrumah KK, Powel Y (2008). Resource Allocation Models and Accountability: A Jamaican case study. J. Higher Education Policy and Management. 30(3): 245-258. |

|

|

|

|

|

Ott SJ, Russell EW (2001). "Leadership and Accountability" In Introduction to Public Administration: A Book of Reading, Parker L, Gould G (1999). Changing Public Sector Accountability: Critiquing new Directions, Accounting Forum, 23 (2):109-135. Pp. 20 |

|

|

|

|

|

Romzek BS, Dubnick MJ (1997). "Accountability in the Public Sector; Lessons from the Challenge Tragedy", Public Administration http://www.emerald.com access 4th January 2011 Rev.Pp. 227-382 |

|

|

|

|

|

Sakyi EK (2009). "Privatization in Five Commonwealth countries –A Review of Implementation and policy achievements", Afr. J. Public Administration Management, 20(2):75. |

|

|

|

|

|

Sekaran U (2000). Research Methods for Business: a Skills Building Approach (3rd ed). New York: John Wiley & Sons. |

|

|

|

|

|

Steffek J. Kristina H (2008). "Emergent Patterns of Civil Society Participation in European and Global Governance" in Jens Steffek, Claudia Kissing and Patricia Nanz (eds.) Civil Society Participation in European and Global Governance: A Cure for Democratic Deficit? Palgrave MacMillan. |

|

|

|

|

|

Stewart J (1984). "The role of information in Public accountability" in Hopwood A. and Tomkins C. (Eds), issues in Public Sector Accounting, Philip Allen, Oxford. |

|

|

|

|

|

Therkildsen O (2000). "Contextual Issues in Decentralization of Primary Education Development", Int. J. Educ. Dev. 20:407-421. |

|

|

|

|

|

Therkildsen O (2001). Efficiency, Accountability and Implementation Public Sector Reform in East Africa and Southern Africa, United Nations Research Institute for Social Development, Programme Paper. |

|

|

|

|

|

World Bank (1995). Bureaucrats in Business: The Economics and Politics of Reform, World Bank, Oxford University Press. |

|

|

|

|

|

Wouter J, Hachez N, Schmitt P (2010). Managerial Accountability: What Impact on International Organizations, Autonomy, 25, Levven/Belgium: Levven Centre for Global Governance Studies. |

|

Copyright © 2024 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article.

This article is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0