ABSTRACT

Hardly any research is available regarding women entrepreneurs in the informal business sector in Eritrea. Results based on a survey of 1,607 women drawn from 12 cities in 6 regions indicate that in setting up an informal business the main sources of initial capital are: the owner’s cash savings; loans from friends and relatives; and interest free credit from suppliers, based on trust. On the positive side, half of the survey respondents indicated that their initial capital had increased since startup, while a significant number stated that it had remained the same, and in a few cases respondents indicated that their initial capital had decreased. Furthermore, it has been noted that Ukub (Rotating Saving and Credit Associations), a form of non-interest bearing savings is a traditional way of network for saving money. Since the majority of the respondents indicated that they purchase their merchandise/raw materials from the formal sector, these informal businesses are assisting formal businesses by serving as important channels of distribution. However, the evidence also reveals that a lack of funds, a lack of demand for products, high cost of materials, and municipal and national laws (and regulations) governing the informal sector represent key problems faced by informal business owners.

Key words: Women, informal sector, financing, networking, economic empowerment, Eritrea.

Women are becoming important players in the informal economy. The informal sector is the primary source of employment (selling directly to consumers), contract labour (producing for another organisation regularly), and casual labour (working on and off for another organisation) (Ramani et al., 2013). The informal economy is very large in developing countries due to the working population. During the past three decades, in most developing countries, growth of employment in the formal sector has stagnated or at best has shown a gradual increase, while the informal economy has increased significantly (Bacchetta, 2009). For instance in, India the informal economy accounts for about 93% of total employment, in Mexico about 62%, inability of the formal economy to absorb the available and in South Africa about 34% (Chen, 2005).

However, the most prevalent forms of work are as street vendors or home-based producers. According to the World Bank, “the informal sector covers a wide range of labour market activities that combine two groups of different nature. On the one hand, the informal sector is formed by the coping behaviour of individuals and families in economic environment where earning opportunities are scarce. On other hand, the informal sector is a product of rational behaviour of entrepreneurs that desire to escape state regulation.”

[1] However, over the past few decades, it has become clear that the informal economy has significant job and income generation potential (Becker, 2004). In particular, women entrepreneurs around the world are major contributors to the economy, as they are making a difference in the socio-economic arena (Iyiola and Azuh, 2014).

Despite an increasing presence in the micro, small, and medium enterprise sectors, women’s lack of access to finance remains one of the key constraints for enterprise growth (Niethammer et al., 2007). Improved access to financial instruments that are appropriate for women, as well as the provision of nonfinancial services, would help women grow and professionalize their businesses into more competitive ventures (Goheer, 2003). Goheer further argues that providing access to finance can be an important tool for the empowerment and development of women, both at the social and political levels. While not a panacea, women’s access to finance is an important tool for poverty reduction (Niethammer et al., 2007). This is particularly important not only for women’s economic empowerment in general but for increasing female employment in the private sector.

Women entrepreneurs often resort to different sources of financing than men. Their businesses tend to be concentrated in the services sector and usually only require a small initial capital outlay and less technical knowledge (UNESCAP, 2005). Carter et al. (2012) indicate that, similar to their developed country counter-parts, in developing countries women’s businesses tend to be younger, smaller and created with fewer resources and, further, they usually operate from home, have low earnings, compete in crowded sectors and production is based on very scarce financial, human and physical resources.

According to Ramani et al. (2013), the traditional role of women as caretakers of children restricts the time they can invest in income generation. Furthermore, societal, religious and other norms also determine the mobility of women and with whom they may interact. This is an impediment to women because interaction within social networks is crucial for the success of business. Social networks enable women to build up their market and open new doors for gaining access to funding. One of the most determinant factors of a successful entrepreneurial venture is the existence of a social network that not only eases credit constraints but can provide access to supply and distribution channels and help in obtaining the necessary licenses to operate (Yueh, 2009).

As in other developing countries, the number of informal businesses in Eritrea, in particular those owned by women entrepreneurs, is increasing. The Government of Eritrea launched its National Macro-Policy in 1994, which advocates for upgrading and improving the human and material capacity of the informal sector to improve efficiency and quality in the production of goods and services. Anecdotal evidence indicates that the Eritrean informal sector attracts many women and contributes a great deal to their income and employment; however, there is lack of relevant data to substantiate this belief. Hence, the main objective of this paper is to investigate the informal business run by women; its size; the number of women engaged in the sector; their income levels, and their economic and social conditions. It was with this intention in mind that this research was launched.

Since this report is the first of its kind for Eritrea, it provides new knowledge regarding the informal business sector in Eritrea in general and the participation of women in this sector in particular. This research highlights the financing, business networking, economic empowerment and constraints of women in the informal business sector. Moreover, it highlights policy interventions needed to empower women and achieve gender equality and equity.

The central theme of this study is to investigate the socio-economic conditions of women in the informal business sector in Eritrea. The approach adopted included a survey and structured interviews targeted at women in the informal business sector in the six administrative regions of Eritrea (Central Region (CR), Western Region (WR), South Region (SR), Anseba Region (AR), Southern Red Sea Region (SRDR), and Northern Red Sea Region (NRDR)). A representative sample of cities from each of the six regional administration areas was selected for the purposes of the survey. Based on expert opinion, employment and logistical reasons, the approach used in selecting the cities for the survey was population size. That is, all large cities with more than 20,000 inhabitants were included in this study.

This study employs mainly quantitative data; however, qualitative data was also used to supplement the quantitative data. Data on women in the informal business sector was collected through a highly structured self-administered questionnaire designed to elicit quantitative data. Primary data was collected in each of the selected cities for all the regional areas of Eritrea. A total of 12 cities were selected for the survey. Care was taken to ensure that a representative sample of women was obtained from each region. Initially it was estimated that a sample of about 1,500 women in the informal business sector would be contacted for the study. We took the percentage distribution of women employed in the six regions working in the following five areas as our sampling base: professional/technical/ managerial; clerical; sales and services; skilled manual; and unskilled manual. However, we excluded agriculture and domestic services because, according to the International Labour Organisation (ILO), informal business is confined to non-agricultural units and non-domestic services. Thus, based on a percentage distribution, the sample desired for this study was 1,504 enterprises. However, to accommodate missing questionnaires, we decided to distribute 1,625 questionnaires. Every single questionnaire was returned and we received 1,607 usable questionnaires, which represents a 98.9 % response rate.

We also collected qualitative data in order to have an in-depth understanding of the working conditions of women operating in the informal economy and to identify the constraints they are encountering in operating their businesses. We interviewed 25 women working in the informal business sector in the Central Region, South Region, and Western Region of Eritrea.

Women and the economy in Eritrea

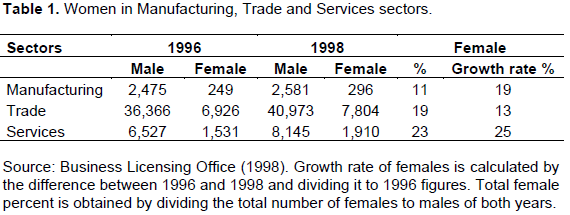

Women play an important role in the Eritrean economy. Many enterprises are owned and run by women, and women make up 30% of the workforce in manufacturing, services, and trade (Hayde, 2001). However, economic and political gender equality is still weak in Eritrea, despite the enactment of mechanisms to empower women and to inform them of their rights. This is primarily due to the women’s limited access to needed resources such as credit and education. The women’s organization, the National Union of Eritrean Women (NUEW) is involved in advocacy and education on key women’s issues; including health, education, micro-finance, and human rights. Table 1 presents a comparative study of the number of women and men involved in the manufacturing, trade and service businesses.

According to the 1996 figures, women own 10-23% (the lowest in manufacturing and the highest in services while the figures for trade remain in the middle) of micro-enterprises in Eritrea. Women-owned enterprises account for almost two-thirds of the enterprises in the production sector (brewing local drinks; basket, broom, mat making; etc.); two-fifths in the trade sector (hotels and guesthouses, petty trade, coffee shops, and retail trade); and one-fourth in the services sector (hair salons and rental services). Female-owned enterprises account for 40% of all employment in micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises. Women-owned enterprises tend to be smaller than those owned by men and employ primarily women workers.

Financing informal businesses

In order to assess the level of capital invested by women in the informal business sector, we asked respondents to indicate the amount of initial capital they spent to start their business. The respondents indicated that, on average, they invested Nakfa 1,454.492 in setting up their informal businesses. Regional analysis (Figure 1) reveals that the mean value of the initial capital investment is highest in the Southern Red Sea Region (Nakfa 3,121.31) and lowest in the South Region (Nakfa 784.17).

In order to ascertain the main sources of initial startup capital in the informal business sector, we also asked respondents to identify the financial source(s) used for establishing their businesses. The information presented in Table 2 reveals that the two major sources of startup financing were the owner’s own cash savings (41%) and loans from friends and relatives (31%). This is not a unique Eritrean phenomenon as empirical studies in the Middle East, Pakistan and North African countries have found that women finance their businesses using personal savings and loans from friends and relatives (IFC; Roomi, 2005). The proceeds from sale of assets, such as gold and jewelry (6%) and loans from suppliers (6%) were also important sources of startup financing.

Loans from suppliers were used not only to start their businesses but also to continue operating their businesses. Many of the respondents acknowledged the ongoing support they received from suppliers of the merchandise that they were selling. Suppliers often extended trade credit to the women engaged in the informal business sector. Based on trust, they allowed the women to buy the goods on credit and gave them about two weeks to sell the goods and repay the money owed. This provides the entrepreneurs with an interest free loan and is the reason why they typically avoid commercial bank loans to finance the purchase of merchandise. The women try to sell the merchandise above cost price and retain the profit in their businesses. The profit they earn helps them to finance their daily bread, their children’s education and clothes. However, the suppliers sometimes dictate the selling price of the goods and this does not allow the women to be flexible in their pricing strategy. Other financial sources used for starting an informal business include support from the Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare, support from Martyrs Trust Fund and divorce settlement proceeds.

The results in Table 2 also indicate a wide variation by region in the sources of capital for financing the startup of an informal business. For example, in the Southern Red Sea region about 81% of the respondents financed their initial capital using their own savings but this only applied to 28% of the respondents from the South region. While the use of micro-financing was quite limited, 4% of respondents in the South Region indicated that they had used micro-financing arrangements from the NUEWs. One interviewee who participated in the NUEWs’ micro finance program shared her experience as follows: “The initial microfinance support that I have received from NUEWs has helped me to establish my business and to operate it profitably. I was successful and repaid my loan and its interest on time. The loan was helpful. However, the loan was a group loan and even though we did not know each other, we were asked to take the responsibility of our group members if they fail to pay. Since my group members were not able to pay, I was neither able to get a new loan nor get my deposits back. In addition, this loan is interest bearing and we resort to trade credit from our suppliers to avoid paying interests. If we had found interest free loans or grants, we would have been flexible in our pricing and we would have profited more.”

Performance of the informal business sector

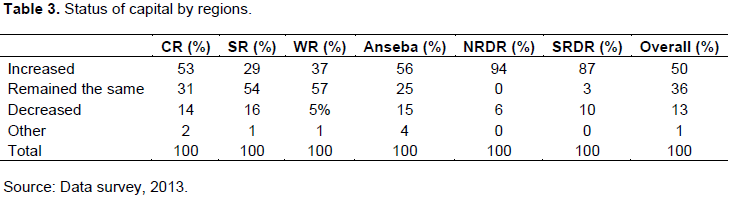

In order to assess the performance of their informal businesses, we asked the women entrepreneurs to indicate whether their initial capital had increased, decreased or remained the same. As shown in Table 3, the majority of respondents (50%) indicated that their initial capital had increased, while 36% of the respondents indicated that it had remained the same and only a few respondents (13%) indicated that their initial capital had decreased.

Again, a regional analysis of the responses revealed considerable variation. For example, 94% of respondents from the Northern Red Sea Region indicated that their capital had increased but this only applied to 29% of respondents from the South Region. Note that the majority of respondents in the Western Region and South Region indicated that their capital had remained the same. In order to provide a more in-depth understanding of the causes for the increase or decrease in the initial capital invested in their informal businesses, we further asked respondents to explain the reason for any increase/decrease in their initial capital investment. The most important reasons provided for the increase in capital include: an increase in the number of customers (55%); an increase in the quantity of merchandise held for sale (20%), and the introduction of new products (variety) in the merchandise holdings (14%). Furthermore, the respondents that reported a decrease in their capital gave the following reasons for the decrease: severe competition in the market (23%); confiscation of merchandise by municipality police (23%); lack of a helper (16%), and various other reasons (23%), such as the theft of money deposited with people.

Banking facilities used by the informal businesses

The information presented in Table 4 shows that the majority of respondents (91%) indicated that they did not hold a bank account in their own name or in the name of their business. A regional analysis of the ownership of a bank account indicated that a higher percentage (26%) of the respondents from SRDR owned a bank account. In CR and SR, only 10 and 9% of the respondents, respectively, indicated that they had a bank account. Over 90% of the respondents from the other regions indicated that they did not own a bank account.

Financing facilities used

In order to assess the financing facilities that women in informal businesses use we asked the respondents to identify the financing sources used for their business. Their responses indicate that 73% did not use any formal financing facility, such as banks or government institutions. Instead, many of the women relied on Ukub; a form of non-interest bearing savings. In Ukub, the members agree to contribute a fixed amount of money each month and at the end of each month one person takes the total contributions collected. This method of financing helps the women working in the informal business sector to save their cash until it is needed. Even though lots are usually drawn to determine who gets the collection each month, at times of need a member can be allowed to take the contributions upon request. About 16% of the respondents indicated that they used Ukub as a form of financing the informal business. About 8.5% of the respondents also indicated that they used bank funding to finance their operations. The responses reveal that the women are typically not using government and development institutional financial support schemes, such as micro-financing programs.

Networking in the informal business sector

Relationships with suppliers

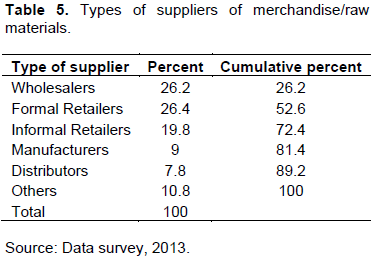

In order to study the vertical and horizontal networking relationships the informal business owners maintain, we asked respondents about their suppliers and customers. The respondents indicated they purchase their merchandise/raw materials from formal retailers (26.4%), wholesalers (26.2%), informal retailers (19.8%), manufacturers (9%), distributors (7.8%), and other different sources (10.8%). It is very interesting to note that more than 52.6% of the respondents indicated that they purchase their merchandise/raw materials from the formal sector of the economy. In other words, the informal businesses are assisting the formal businesses by serving as an important distribution channel. In the open interviews we also learned that people perceive the prices of goods sold on the streets as being cheaper than those sold in the formal shops. Moreover, the suppliers provide credit sales to the informal business owners based on trust. This is helping the owners of the informal businesses to sell more products and to develop good business relationships with their suppliers. Table 5 presents the type of suppliers associated with the informal business sector.

Relationship with customers

It seems that the majority of informal business customers are women. About 41.3 and 40.7% of the respondents stated that their customers are mainly women, or both men and women equally, respectively. Indeed, only 9.7% of the respondents stated that their customers are mainly men, while 3.3% mentioned children as their customers. Private, government, and other institutions only represent about 6.1% of the informal business customer base. Further, the informal business sector customers are mainly passer-bys. Some respondents also stated that, to a limited extent, they sold on credit to acquaintances such as government workers, neighbors and relatives. An interviewee reported the following: “I get the merchandise on credit from suppliers and I also sell on credit to my acquaintances in particular those who are workers. I give them a two or three months credit and they pay when they get their salary.”

Monthly income of informal businesses

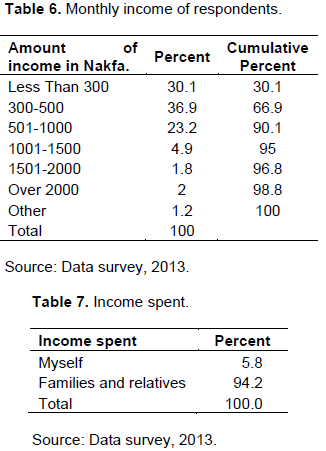

In order to assess the income generated by working in the informal sector, we asked respondents to identify their monthly income level in categories. Their responses are provided in Table 6.

The most notable feature of Table 6 is that a very high proportion of respondents indicated that their monthly income is either less than or equal to Nakfa 500 (66.9%). Moreover, 23.2% of the respondents indicated that their monthly income is between Nakfa 501 and Nakfa 1,000. The remaining 9.9% of respondents indicated that their monthly income is above Nakfa 1,000. In addition, around 2% of the respondents stated that their monthly income exceeds Nakfa 2,000.

These figures clearly illustrate that the monthly income of informal businesses is not enough to cover the daily livelihoods of most women working in the informal business sector and their families. In effect, 75.4% of respondents stated that, their monthly income is not enough for their daily subsistence. Also, people have a general attitude that purchasing from formal businesses provides a better warranty than purchasing from the informal business sector.

Economic empowerment of women through informal business

In order to assess the economic empowerment of women working in the informal business sector, we collected information on how the entrepreneurs spend their income and whether they are generating enough profit for their families. Their responses are presented in Table 7.

As can be seen from Table 7, 94.2% of the respondents stated that their income is spent on financing the needs of their families and relatives, while 6% of the respondents reported that they spend their income on themselves. One interviewee elaborated on the contribution of her informal business income in supporting her family as follows: “To some extent, this business is helping us improve our life. Even though we are not saving, it is helping us get our daily bread. This business has helped us to avoid begging. It is helping us feed our children. Moreover, it is helping us both in raising money for our family and keeping our children with us here. No other job can give us this opportunity.” In addition, three quarters of the respondents indicated that the income they derive from their informal business is not enough for their families, while one quarter of the respondents said yes it is enough.

The survey indicated that on average Nakfa 1,454.49 is invested in setting up an informal business and the main sources of initial capital are the owners’ cash savings and loans from friends and relatives. Half of the survey respondents indicated that their initial capital had increased while a significant number stated that it had remained the same, and in the case of few respondents their initial capital had decreased. Given that a majority of the respondents purchase their merchandise/raw materials from the formal sector of the economy, it seems that informal businesses are assisting formal businesses by serving as an important distribution channel.

Many scholars seem to agree that informal businesses can become effective creators of employment, income and economic growth. However, informal enterprises are (in many cases) unable to realize their full potential because they lack access to: suitable work places and facilities; markets; finance; technology; information; training; and business skills. In addition, excessive government rules and regulations, together with cumbersome and costly procedures, appears to be hindering the growth of many informal businesses.

These obstacles are more or less interlinked and create a vicious cycle of poverty and high risk. For instance, an important reason for the lack of finance and other business skills within the informal business sector is because owners within this sector are typically unable to access: financial institutions, such as banks; training and education institutions; marketing and consultancy firms; etc. Indeed, these obstacles also create barriers to entry within the formal economy.

Accordingly, the current position taken by many stakeholders is that, as the informal economy is going to persist and given its contributions to national economies, governments have a responsibility to: correct policy biases against the informal sector; and develop laws, policies and programs that recognize the importance of this sector. This does not mean that governments should not restrict and regulate the sector when and where necessary. Governments should seek to increase the productivity of the sector and improve working conditions; particularly for women.

The results from this survey provide a glimpse of the socio-economic situation of women engaged in the Eritrean informal business sector. The study also highlights some of the key problems faced by operators within the informal sector in general, and women in particular. Among the major problems faced are: a lack of funds; a lack of demand for products; high cost of materials; and municipal and national laws and regulations governing the informal sector.

Poverty caused by lack of money drove many of the women to engage in informal businesses. However, the women reported that a lack of funding is a major constraint they face in operating their businesses. The women entrepreneurs mainly use trade credit to finance their operations. However, the creditors dictate the selling price in some circumstances and also require quick payment (2-7 days). Many respondents felt that this kind of arrangement did not give them the flexibility they needed when determining their own selling prices.

Mostly the entrepreneurs are selling their products to a passerby. In addition, there is high level of competition in the informal business sector because many are resorting to informal businesses to alleviate poverty and as a means of subsistence. Moreover, during economic downturns people lack purchasing power and, therefore, primarily buy food products. Thus, they have less money to spend on clothes, which is where most of the women engaged in the informal business sector operate. At the same time, the cost of goods/raw materials they are purchasing appears to be rising which, in turn, is eroding their profit margins. Thus, a lack of demand for their products coupled with the increasing cost of raw materials is presenting a significant problem for women operating businesses in the informal sector.

In general, licensing in Eritrea is easy and most enterprises are regulated. However, one requirement for opening a business is space, which is another major constraint many women entrepreneurs also face. Due to a lack of space, many women in the informal sector are unable to get a license to trade and this impedes their operation. In summary, it appears that the most important source of assistance which could positively impact on improving the functioning of businesses within the informal sector is access to credit (finance) and goods/raw materials. Our research findings indicate that financial support in the form of loans and/or grants could help women engaged in the informal sector acquire the goods/raw materials needed for their businesses.

Microfinance appears to be the only successful model for providing non-collateral small-scale credit to operators within the informal economy. It is recom-mended that other sources of funding, besides their own savings, be made available to women starting up informal businesses. Accordingly, access to Eritrean microfinance institutions could help women augment their working capital and expand their businesses.

Moreover, support programs for education, skill building and training should be made readily available to women to help them improve their business, marketing and production skills. Gender-specific and tailor-made training might be a useful strategy to address gender inequalities. Although considerable assistance is provided by the NUEW, and the Government, in the form of finance and other assistance, continuous support for this sector is crucial. The provision of favorable policies and a legal environment that lowers the cost of establishing and operating a business (such as: simplified registration and licensing procedures; appropriate rules and regulations; and reasonable and fair taxation policies) would be beneficial to women operating in the informal economy. In addition, establishing marketing cooperatives at the regional level (under the umbrella of the NUEW) to give voice to the poor women working within the informal economy could help to reduce the constraints their businesses are facing. It could also help the NUEW and the Government to more easily approach these women.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Bacchetta M, Ernst E, Bustamante JP (2009). Globalization and Informal Jobs in Developing Countries, ILO.

|

|

|

|

Becker KF (2004). The Informal Sector, Fact Finding Study, Department for Infrastructure and Economic Cooperation, SIDA.

View

|

|

|

|

|

Carter S, Marlow S, Bennett D (2012). Gender and entrepreneurship. In: Enterprise and small business. Financial Times (3rd). Pearson Education, pp. 218-231.

|

|

|

|

|

Chen MA (2005). Rethinking the Informal Economy: Linkages with the formal economy and formal regulatory environment (No. 2005/10, Research Paper, United Nations University.

|

|

|

|

|

Hayde G (2001). Women's Employment and Micro Enterprise Development in Eritrea, Development Alternatives Inc.

|

|

|

|

|

Iyiola O, Azuh D (2014). Women Entrepreneurs as Small Medium Enterprise Operators and their Roles in Socio-Economic Development in Ota, Nigeria, Int. J. Econ. Bus. Finance 2(1):1-10.

|

|

|

|

|

Niethammer C, Blackden M, Kaltenborn-Stachau VH (2007). Women Entrepreneurs and Access to Finance in Pakistan, Women's Policy J. 4:1-12.

|

|

|

|

|

Ramani S, Thutupalli A, medovarszki T, Chattopadhyay S, Ravichandram V (2013). Women Entrepreneurs in the Informal Economy: Is formalization the only solution for business sustainability, Working Paper, 2013-018, United Nations University.

|

|

|

|

|

Roomi MA (2005). Women Entrepreneurs in Pakistan: Profile, Challenges and Practical Recommendations, University of London, School of Management.

|

|

|

|

|

United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and Pacific (UNESCAP) (2005). Developing Women Entrepreneurs in South Asia: Issues, Initiatives and Experiences, Bangkok: UNESCAP.

|

|

|

|

|

United Nations Industry Development Organization (UNIDO) (1995). Draft Manual on Diagnosis and Restructuring of Industrial Enterprises: with emphasis on agro-industries, Enterprise and Private Sector Development Division, UNIDO.

|

|

|

|

|

World Bank (1998). "Eritrea at a glance", World Bank Tables, Washington D.C.

|

|

|

|

|

Yueh L (2009). China's Entrepreneurs, World Dev. 37(4):778-786.

Crossref

|

|