ABSTRACT

The study explored the reasons of rejection, acceptability and usage of the bond coins by Zimbabweans as well as the challenges they faced in their usage. To achieve the overall aims of the study, an explanatory sequential design (ESD) of mixed-methods was used to explore the people and institutions’ views on the rejection and acceptability of bond coins in Zimbabwe. A sample of 100 vendors, 60 commuter operators, 20 economists, 10 reserve bank of Zimbabwe officials, 10 banks, 100 supermarkets and 100 informal traders were used. Quantitative data was gathered using a questionnaire whilst qualitative data was generated using telephone interviews with public institutions, banks and professionals. Survey data was captured in SPSS and presented in the form of tables and graphs while descriptive statistics were computed and used in the interpretation of the findings. The findings showed that bond coins were initially rejected when they were introduced in December 2014, because people felt that the RBZ was clandestinely introducing the local currency through the back door. With the deterioration of the South African rand (ZAR) against the US Dollar (USD) in 2015, the results showed that the acceptability of the bond coin spiked. Evidence showed that charges levied by banks to the public for transacting in rand coins and the fall of ZAR were the major drivers to the acceptability of the bond coins. Thus, the research indicated that the demonetization of the rand coins in Zimbabwe was a result of public perception on the bond coins. The findings showed that there is a possibility that the public may begin to shun the bond coins once the rand rebounds against the USD. The study recommended an increased awareness campaign by the apex bank to allay fears inherent in Zimbabweans on the use of bond coins and to come up with a raft of measures to protect the ordinary traders and citizens. The research further recommends that the RBZ further play its oversight role to the maximum.

Key words: Bond coin, dollarization, problems, challenges.

In April 2009, Zimbabwe had to abandon its own currency and simultaneously adopted a collection of currencies including the South African rand, Botswana pula and the US dollar. This was after a prolonged period of hyper-

inflation which peaked at an astounding monthly rate of 79.6 billion percent in mid-November 2008.At that point, as was expected, people simply refused to use the Zimbabwe dollar (Hanke, 2008: 9), and the hyperinflation came to an abrupt halt. The Federal Bank notes were then used in large value transactions, while the rand coinage from neighboring South Africa was used for smaller transactions. The transacting Zimbabweans were then faced with the problem of coins in conducting trade (Daily News, 2014). The demand for small change was visible and items like sweets, ball point pens, vouchers and gums were used as coin-substitutes.

In light of the above, due to the fact that importing coins from USA to Zimbabwe was expensive, the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ) began to release Zimbabwean bond coins on December 18, 2014 after realizing the negative implications of 100% dollarization of the economy. The mistake Zimbabwe did was to disown the Zimbabwean dollar and adopting the United States dollar without making provision in terms of change for lowly priced goods and services (Mangudya, 2015). Thus in a way bond coins were introduced as a measure to reinforce the multicurrency system by making change available in United States currency and to facilitate correct pricing of goods and services through the bond coin system (Moyo and Mbira, 2016). These were the first Zimbabwean coins since 2003. The coins were denominated at 1, 5, 10, and 25 cents and were pegged to the corresponding values in United States currency (Moyo and Mbira, 2016). A 50 Cent Bond Coin was finally released in March 2015 (Herald, 2015).

According to the RBZ, coins were being issued to remedy lack of small change resulting from the absence of a solid seignorage contract with the USA and other countries whose currencies were being used in the multi-currency regime that arose in 2009 (RBZ, 2014). Other dollarized nations such as Panama, with the balboa, Ecuador and East Timor with the centavo introduced their own coins which were used alongside the US dollar (Jacome, 2004). The centavos and balboas were equivalent to the US cents. In East Timor, the notes and coins were accepted by the public without full knowledge of whether the currency was genuine or not (BPA, 2010).

The introduction of the Bond coins was widely greeted with skepticism as it was believed to be a gradual introduction of Zimbabwe’s own unreliable currency (Mail and Guardian, 2015,Telescope, 2014). Soon after the release of the coins on the market, street vendors, commuter bus operators (kombis), and fuel service stations rejected the coins, insisting that their customers use US dollars to settle for goods and services. Circulation of the coins seemed to have been confined to major retail shops such as OK Zimbabwe and TM Pick and Pay Supermarkets.

However, John Mangudya, the Governor of the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe denied that the Zimbabwean dollar was being reintroduced, saying such a move would be "economic suicide (Herald, 2015). The governor said it would take about 4 to 5 years for the local currency to be reintroduced. The government went onto launch the coins regardless of some of the concerns that had been raised.

Zimbabweans have been transacting with both ZAR and USD since 2009, but they have been setting prices in the latter. The dollar, not the rand, is the unit of account. This means that any transaction involving rand is inconvenient as it requires a foreign exchange conversion back into dollars prior to consummation. Over the last few years, Zimbabweans have solved this problem by the informal adoption of a "street" rate of ten rand-to-the dollar. They use this rate as a rule of thumb even though the market exchange rate has deviated quite far from it. The advantage of a nice round number is that it reduces the calculation burden of a two currency system.

Of late, there was a sudden change in public perception on bond coins by Zimbabweans who begun to embrace bond coins in earnest. The experience which Zimbabwe have had on the bond notes seems to argument a widely believed economic theory thought that the acceptance of an currency in an country rests with the households’ perceptions (users) than the policy makers. At the same time, no one wants South African currency anymore, with retailers and banks increasingly rejecting rand coins (Sunday Mail, 2015). The bond coin has become the most valuable currency and they made some positive impacts (Newsday, 2015).

The paper seeks to answer the following research questions:a) Did the introduction of bond coins prove helpful to Zimbabweans?

b) What are the reasons behind the rejection and acceptance of the bond coins in Zimbabwe?

Bond coin defined

According to the RBZ’s FAQ on bond coins, the value of the bond coins is guaranteed by a $50million facility with the African Export-Import Bank (Afreximbank), hence the term bond coin (RBZ, 2015). The bond coins are denominated in 1, 5, 10, 25 and 50 cents and they can be converted anywhere in Zimbabwe into United States dollars at the nearest bank, shop or supermarket in Zimbabwe. This convertibility of the bond coins into US dollars and vice-versa on a one-to-one basis guaranteed by RBZ through a bond facility with an international bank has sustained the perpetual value of the coins in United States dollars. This is why banks accept them and issue customers United States dollars for the equivalent value of coins. This has been a comfort zone for the public (Newsday, 2015). The total value of the coins introduced was US $10 million backed by a $50 million dollar denominated bond translated to 2% of the total bank deposits in the country.

Use of bond coins

Alleviate problem of small change

According to Mangudya (2015), the bond coins were introduced to assist in the restoration of proper pricing models, alleviate problems associated with change, issuance of change vouchers and change in the form of unwanted goods. Previously lack of change in the economy contributed to the overpricing of commodities and forced consumers to overspend as a result of the lack of change thereof (Mangudya, 2015).

To aid divisibility of the currency

Moyo and Mbira (2016) went further to suggest that in a low inflation country, it is a requirement that the unit of exchange and unit of account be divisible as much as possible. A good example is in the economy of Japan, which is a very low-inflation economy and the Japanese yen is a very divisible unit of currency. This allows businesses to set optimum prices for goods and services right to the smallest possible margin (Chigome, 2015). This aspect benefits both consumers and business people as customers get exactly what they want and pay exactly what it is worth, rather than a rounded off figure (Chagonda, 2010).

To remove price distortions

The lack of coins in the economy had contributed to the overpricing of goods and services and forced consumers to overspend as a result of the lack of change (Mangundya, 2015). With the advent of the bond coins, both the consumer and the producer were suffering as the manufacturer was not facing the correct demand for the product. Moreover, the consumer was being short-changed by paying more than they should. A more accurate determination of price points to match demand for goods and services was made possible by the availability of small change meaning producers could reduce production to efficient cost levels, matched by true demand in the market.

Public perception on bond coins

The hyperinflation period of 2008 left unhealed wounds in Zimbabweans’ psychology on how they think about money, its value and future (Makoto, 2012). Accordingly, Bonga et al. (2014) were of the firm belief that Zimbabweans simply do not trust their government and the RBZ. According to Nyoni (2015) and Moyo and Mbira (2016), upon introduction of the bonds coins, they were rejected. The reasons for rejection were rooted in the New Classical School of Thought which emphasizes on the role and importance of the Central Bank’s reputation and issues to do with time inconsistency, rational expectations, confidence and credibility. According to Perrier and Amano (2000), credibility is of paramount importance when it comes to public confidence in the Central bank’s determination in meeting its goals. When the bond coins were introduced in December 2104, vendors, filling stations, informal traders and kombi operators rejected the coins because of the credibility of the RBZ’s reputation of macro-economic mismanagement. Nyoni (2015) noted that recovery of the economy without confidence was an uphill task. Due to lack of confidence in the monetary policy, the public perceived the introduction of bond coins as the reintroduction of the Zimbabwe dollar and expected prices to rise due to an increase in liquidity brought about by the introduction of bonds. The introduction of the bond coins was perceived not to be compatible in the short run as the public saw it as a ploy to reintroduce the Zimbabwe Dollar in the long run (Nyoni, 2015). Thus, the bad reputation earned by the RBZ led to the rejection of the bond coins.

However, in April of 2015, the public started to bond with the bond coins (Herald, 2015). This was due to public perception over the value of the bond coin against the USD. The other reason why Zimbabweans embraced the previously unpopular currency could be as a result of the fall of the ZAR against the USD.

In view of the nature of the problem under study, a sequential explanatory mixed method research design was considered the most appropriate to collect and investigate views on acceptability and rejection of bond coins in Zimbabwe. Consistent with the design, data were collected in two phases. First, the researchers collected and analyzed results of quantitative data (Quantitative phase) and then followed-up with a qualitative data collection from key interviews which were carried out with key institutions and policy makers. In the quantitative data collection, the study made use of random sampling in the selection of respondents who participated in this study. The use of random selection was adopted as it allowed that all members of the public were given an equal chance of being selected, thus in a way reducing bias selection of respondents. Self-administered questionnaires were a major tool of data collection. The questionnaire was administered to the informal traders, vendors, commuter bus operators and supermarket managers in Masvingo, Harare, Gweru, Mutare and Bulawayo over a period of one month, that is, in November 2015. Out of the 360 questionnaires administered, 335 were returned representing a response rate of 93%. The high response rate may be attributed to the interest that the research generated and its economic importance upon completion. The questionnaire was divided into two sections. Section A comprised of biographical data such as age, gender and highest qualification of the respondents, while Section B captured information on the rejection, acceptability and use of bond coins on a five point Likert scale where respondents indicated the degree of their agreement on various statements. The Statistical Package for Social Scientists (SPSS) was used in the analysis of the data were computed and employed in the interpretation of results. Data was thus presented in the form of frequency tables and graphs.

The second phase of the data collection process was to collective qualitative data through follow up interviews with economists based in Harare and Bulawayo and banks and RBZ officials based in Harare within the same period. This was necessary to compliment the results of the survey data collected by the use of self-administered questionnaire. The second phase was used as a follow – explanatory approach to offer a better evaluation of the perceptions of individuals on acceptability and rejections of bond coins. Institutions and key people (economists, banks, RBZ and supermarkets) who had better information on the policy framework on bonds coins were interviewed. The population for the study comprised of vendors, commuter bus operators, supermarket managers, Economists, RBZ officials and informal traders. The sample consisted of 100 informal traders, 100 vendors, 60 commuter bus operators, 100 supermarket managers, 20 economists, 10 banks and 10 RBZ officials.

Usefulness of bond coins

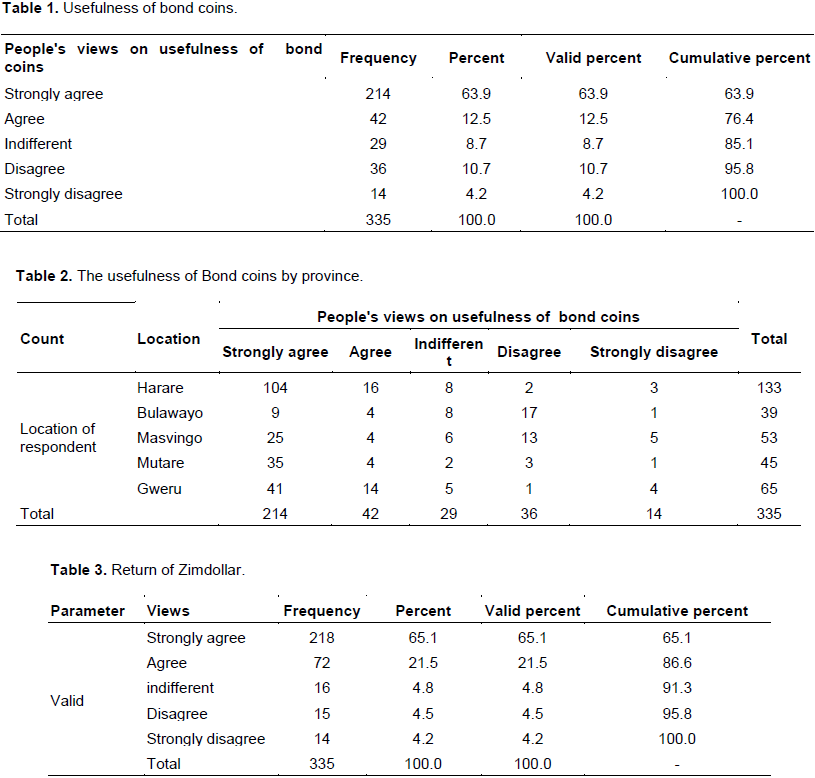

The vendors, commuter bus operators, supermarket managers, economists, RBZ officials and informal traders were asked as to whether they think that the introduction of bond coins proved helpful to the public. Most people believed that the introduction of the bond coins did benefit Zimbabweans and this is represented by approximately 76% of the respondents who either strongly agreed or agreed (Table 1). Reasons given ranged from removal of price distortions and lowering of prices. Most goods were priced at less than a dollar.

Degree of usefulness of bonds coins by province

The results of the survey show that the degree of usefulness of bond coins varied with the province where the respondents were located. Bulawayo and Masvingo (17 and 13, respectively) had more numbers of respondents who disagreed that the bond coins were much useful. The results show that more respondents who strongly agreed that the bonds coins were useful came from Harare (104). This shows that people from Harare benefited more on bond coins than people in other provinces. The results could be explained by the fact that bond coins were much concentrated in Harare when they were introduced. Few bond coins which circulated in other provinces such as Bulawayo were wiped away by speculators who would go in other smaller towns to buy bond coins at a rate of 5ZAR: 50 cents equivalent bond coin to benefit 20 cents from the depreciation of the rand against the USD. Most vendors mostly in rand linked cities such as Bulawayo lost as they accepted the remaining rands in the market at their vending sites but would not get a 5ZAR:50 cents exchange rate in shops when they would reorder their stocks. They were now forking more rands to buy a 1 US$/ bond valued product because of the depreciation of the rand. The lack of more bonds in circulation in these provinces made the disadvantaged poorer.

Reasons for the rejection and acceptability of bond coins

This subsection presents the research findings in form of a table showing frequencies of the extent of rejection and acceptability of bond coins as well as the use of the bond coins.

Reasons for rejecting bond coins

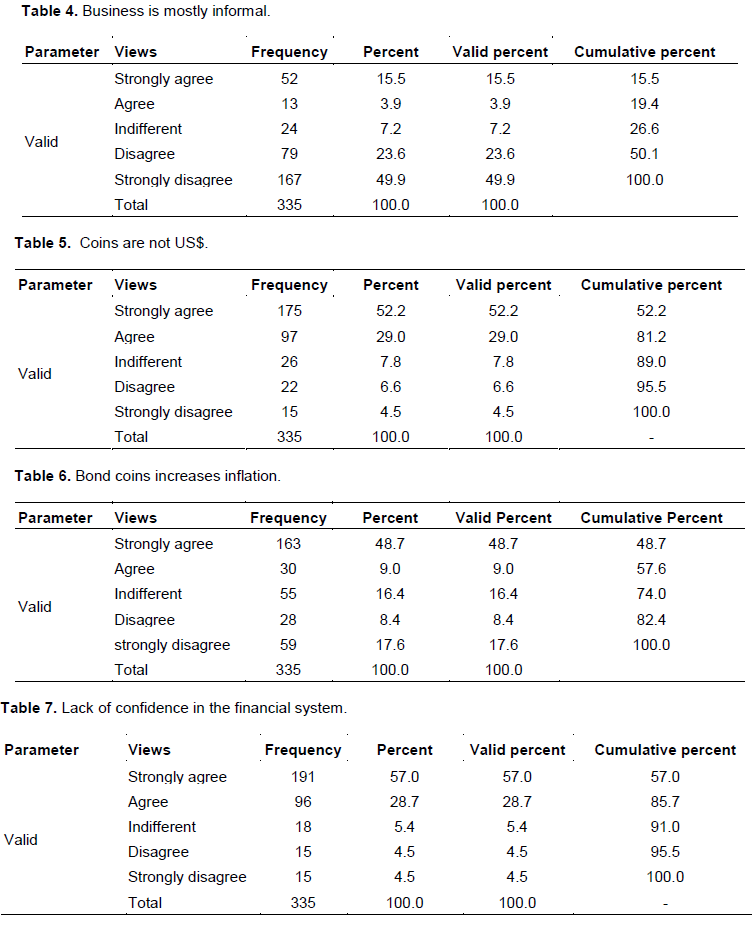

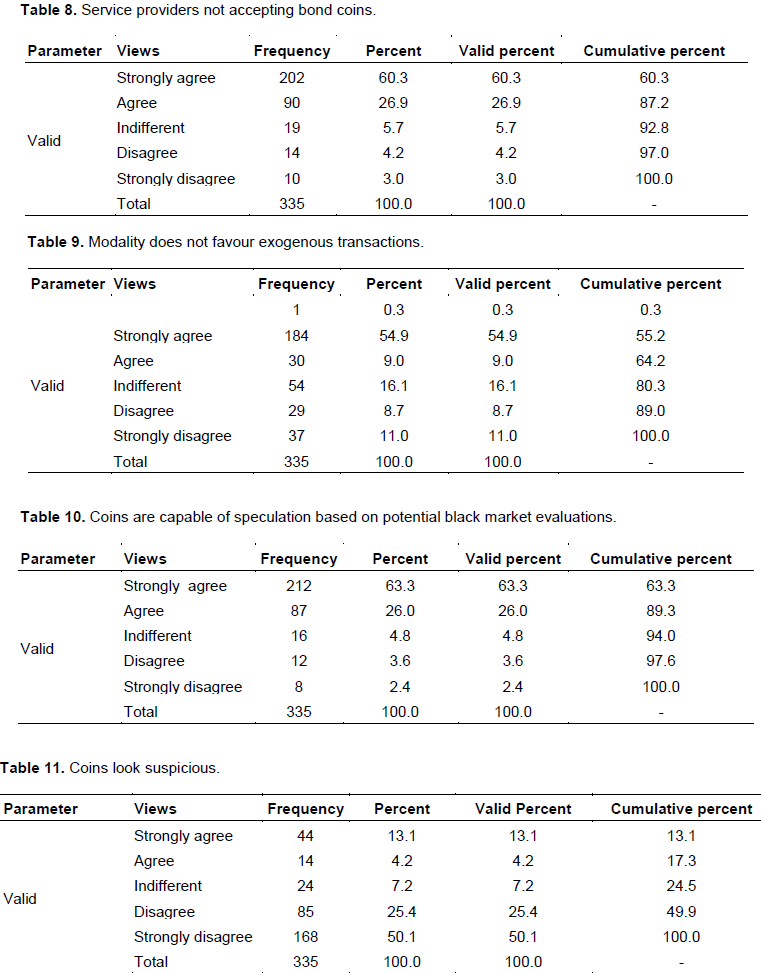

Tables 1 to 11 present responses as to the reasons why the bond coins were rejected when they were first issued.

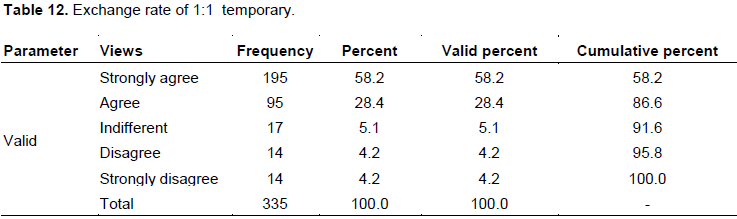

Chief among the reasons why bond coins were rejected was public perception that the coins were linked to the return of the Zimbabwe dollar (Zim dollar) that ravaged Zimbabweans lives previously. This is evidenced by a cumulative frequency of 86% rate of respondents who either strongly agreed or agreed with the above reason. The reason was in sync with Bonga et al. (2014)’s findings that public perception. 87.2% felt (strongly agreed and agreed) that the other major reason for rejection was that service providers like filling stations were rejecting the coins. In addition 89.3% were of the view that coins had unquantifiable store of value which was liable to fluctuations based on potential black market evaluations and thus they were rejected. 82% were of the view that the coins were rejected on the basis of a lack of confidence in the monetary system.

Thus, a lack of trust, according to the New Classical school of thought is a major factor in determining the acceptability of any Central Bank policies. Such lack of trust led to the rejection of the bond coins. Those who thought the exchange rate of 1:1 would not hold for long constituted of 86.6% cumulatively. The results also showed that 81.2% were of the view that since paying the coin bearer US dollars was not constitutionally mandated, the bond coins were rejected.

The results also noted that business being mostly informal, introduction assuming a closed economy, bond coins looking suspicious and bond coins increasing liquidity were weaker reasons for the rejection of the coins. This is evidenced by the 19.4, 55.2, 17.3 and 57.6% disagreeing rates, respectively. Unlike in other economies that dollarized, Zimbabweans had reasons for not accepting the coins while in those nations the populace accepted the centavos and balboas without having the knowledge whether they were legal tender or not.

Reasons for accepting the bond coins

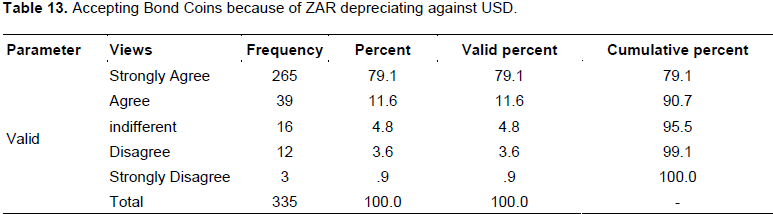

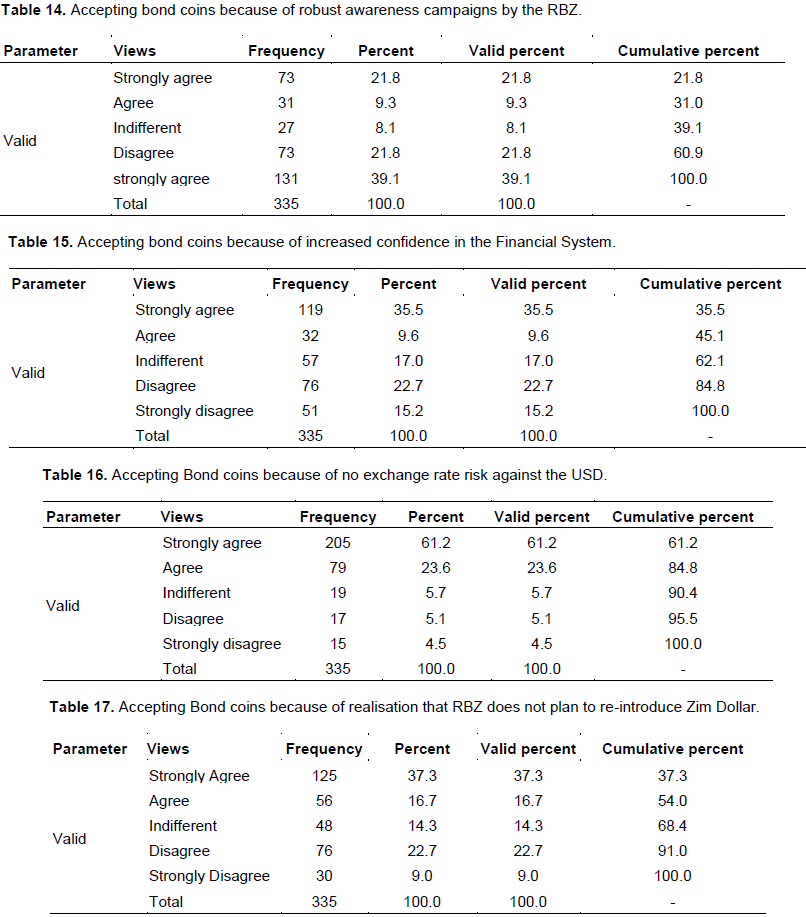

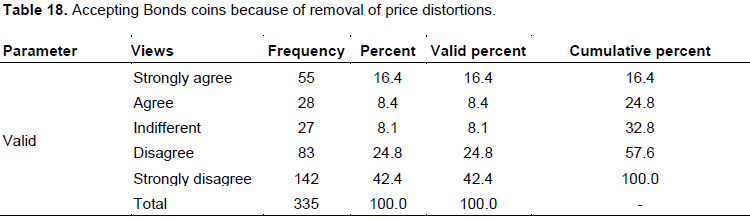

Tables 13 to 18 present the responses in terms of the reasons as to why the bond coin was finally accepted by the transacting Zimbabweans.

The tables revealed that 90.7% of the respondents were in agreement that the acceptability of the bond coins was mainly due to the fall of the South African Rand against the US Dollar. The other major reason why the bonds coins were embraced was the absence of the exchange rate risk of the bond coin against the US Dollar and the existence of the exchange rate risk in using the rand. This is evidenced by the fact that 84.8% of the respondents were in agreement. The bond coins were set at par with the US dollar, hence the nonexistence of exchange rate risk. Thirty one percent agreed that realization by the masses that the use of bond coins was not a ploy by the central bank to reintroduce the now defunct Zimbabwe dollar. Therefore, the three major reasons as to why the bond coins finally bounced back after initial rejection were the fall of the ZAR against the USD, absence of the exchange rate risk between the bond coin and the USD as well as the realization by the masses that the RBZ was not of the idea to reintroduce the Zimbabwe dollar which is represented by the a cumulative agreement percentage of 54.

Only 24.8% of the respondents agreed to the fact that removal of price distortions contributed to the acceptability of the bond coins. The table also revealed that 69% were in disagreement to the idea that robust campaigns by the RBZ led to the acceptability of the coins. Approximately fifty five percent of the respondents also disagreed to the fact that increased confidence in the financial sector contributed much to the bond coin bouncing back. The removal of price distortions, robust campaigns by the apex bank and increased confidence in the financial system were noted as weak reasons for the acceptability of the bond coins. These results were justified and explained by interviews with RBZ officials and economists who revealed that bond coins were accepted mainly because of the depreciation of the Rand against the US$. Individuals, vendors and supermarkets preferred to hold and transact in bond coins which were at par with US$ than in rand terms mainly to curb against loss of value of the rand. Infact, bond coins became “real money” as they could store a value as compared to rands.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

This study examined the extent of the rejection, acceptability and use of bond coins in Zimbabwe in the multi-currency era. The results of the study showed that on the basis of the historical challenges that Zimbabwe has faced regarding its currency, there was very littleprobability that the bond coins where going to get an automatic acceptance. Thus initially the bond coins were rejected. The study revealed that the generality of Zimbabwe developed a wait and see approach to the acceptance of the bond coins, while leading retailers like OK and PnP adjusted their prices in order to correct price anomalies. With the seemingly clear benefits of the removal of price distortions, the public did not accept the use the bond coins.

Thus, it was concluded that the acceptance and rejection of the bond coins solely rests on public perception as well as fluctuating exchange rates.

The researcher therefore came to a conclusion that the rejection of the bond coins were a result of the attitude of the public towards the coins as well as the bad reputation that the RBZ earned and that its acceptance was mainly due to the demise of the South African Rand.

Since the acceptability of the bond coins were a result push factors, that is the depreciating rand and increased bank charges for using rand coins, it is easy for the rand coin to bounce back should the rand appreciates against the green back to a certain extent.

Based on the research findings and conclusions earlier, the following are recommended for the RBZ and other stakeholders involved:

(1) RBZ to carry out education and awareness campaigns on the bond coins and assure stakeholders that it may not be the return of the Zimbabwe Dollar.

(2)The Apex bank to ensure that there is no possibility for counterfeit coins and eradicate challenges regarding change and exchange rates.

(3) RBZ manages the social media well as it has the effects of sabotaging the positive results of the bond coins so far realized

(4) Retailers to seek competitive advantage through lowering prices by a few cents.

(5) Commuter omnibus operators and vendors accept the coins as legal tender.

(6) RBZ maintains bond coins at par with the US$.

(7) The Central Bank takes appropriate actions to prove transparency in which it conducts its business and that the public is satisfied.

(8) RBZ to come up with full deposit insurance system to ensure assets are ring-fenced should the unthinkable

happens

(9) The economy to adopt a Money Flow Index Oscillator

measuring fiscal inflows in and out of the money ecosystem.

The author has not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Behnke A (2008). Ecuador in pictures. 21st Century Books ISBN 08 22585731. P 68Bonga WG, Chira F, Chemina J, Strient MV (2014). World De-Dollarization: Economic Implication of De-Dollarization in Zimbabwe (Introduction of Special Coins). Available at SSRN 2534972.

|

|

|

|

BPA (2010). Know your currency, Banking and Payments Authority of East Timor, East Timor.

|

|

|

|

|

Chagonda T (2010). Dollarization of the Zimbabwean economy: Cure or curse? The case of the teaching and banking sectors. In Coterie Conference on the Renaissance of African Economies. Dar EsSalam,Tanzania. pp. 20-21.

|

|

|

|

|

Chigome J (2015). A Reflection on Sustainability of Dollarisation in Zimbabwe. Int. J. Adv. Res. 3(7):306-318

|

|

|

|

|

Hanke SH (2008). Zimbabwe: Hyperinflationto Growth. Harare Zimbabwe. New Zanj Publishing House.

|

|

|

|

|

Herald The (2015). $9m bond coins now in circulation, Harare.

|

|

|

|

|

Jacome H (2004). The late 1990s Financial Crisis in Ecuador. Institutional Weaknesses, Fiscal Rigidities and Financial Dollarisation at Work, International Monetary Fund Working Paper 04/12

|

|

|

|

|

Mail and Guardian The (2014). Zimbabweans skeptical of new bond coins, Johannesburg , South Africa, Published 22 December 2014 Retrieved 12 December 2015

|

|

|

|

|

Makoto R (2012). Dollarization and the way forward in Zimbabwe. Journal of Strategic tudies: A Journal of the Southern Bureau of Strategic Studies Trust: Joint Research Programme of the Ministry of Finance. The Zimbabwe Economic Policy and Research Unit and the University of Zimbabwe 3(1):51-67.

|

|

|

|

|

Mangudya JP (2015). Zimbabwe Monetary Policy Statement, Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe.

|

|

|

|

|

Moyo S, Mbira L (2016). The Impact of Bond Coins in Business Transactions at Nkayi Growth Point in Zimbabwe. Int. J. Bus. Manage. 4(1).

|

|

|

|

|

Newsday (2015). The Positive Impact of Bond Coins, Harare.

|

|

|

|

|

Nyoni T (2015). Reasons for the rejection of the Zimbabwean Currency, Publications.

|

|

|

|

|

Perrier P, Amano R (2000). Credibility and Monetary policy; Research Department; Bank Of Canada Review; Canada.

|

|

|

|

|

RBZ (2015). Frequently asked questions about Bond Coins, Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, Harare

|

|

|

|

|

Sunday Mail The (2015). Business: Tethering problems for bond coins, Ignorance breeding skepticism.

|

|

|

|

|

The Daily News (2014). RBZ unveils bond coins.

|

|

|

|

|

Telescope The (2014). Zimbabwe launches new coins to solve change shortage. Published24 December 2014, Retrieved 12 December 2015.

|

|