ABSTRACT

The aims of the study were to isolate and identify the Candida species from clinical cases of candidiasis and to determine their anti-fungal susceptibily. Clinical samples such as vaginal swab, nails scrapings and squama were submitted to the Mycology Unit of Institut Pasteur of Côte d’Ivoire, from 2011 to September, 2015. Samples were screened for the growth of Candida species, which were then identified by chromogenic medium CandiSelect®4 and Auxacolor 2® (Biorad). Antifungal susceptibility was performed by ATB Fungus 3® of Biomérieux with the drugs Amphotericin-B, Flucytosine, Fluconazole, Itraconazole and Voriconazole. A total of 924 yeasts were isolated and Candida albicans was the common species isolated (40.3%), followed by Candida glabrata (29.2%) and Candida tropicalis (17.2%). Most of the isolates were collected from vaginal swabs 781 (84.5%) followed by squama 49 (5.67%). The results of the antifungal susceptibility test against vaginal Candida species indicated that 96.8 and 96.3% of the vaginal yeast isolated were susceptible to amphotericin B and voriconazole, respectively. The susceptibility rate of the yeasts was 67.7% to flucytosine, 91.8% to fluconazole, and 86.6% to itraconazole. A high proportion of resistance to Itarconazole was observed with all of the isolates tested. The study indicated that the vaginal Candida species were less susceptible to the flucytosine than to any azole drugs. In contrast, the susceptibility to flucytosine against Candida species isolated from other clinical samples was relatively good. The present study revealed that C. albicans was the most commonly found yeast from various clinical specimens; and reported that the fives antifungal drugs tested are still active against the Candida species.

Key words: Candida species, fluconazole, amphotericin B, itraconazole, flucytosine, voriconazole.

The Candida species could infect a wide spectrum of human hosts, ranging from benign colonization of the skin and mucosal surfaces to invasion of the bloodstream with dissemination into the internal organs. Candida spp. infections are recognized as a major challenge in public health, commonly associated with high morbidity and mortality since its diagnosis and treatment present difficulties and high healthcare costs (Arnold et al., 2010).

The genus Candida includes several species involved in human pathology. Candida albicans is by far the most common species causing infections in humans. Increase in the prevalence of yeast infections caused by non-albican Candida such as Candida glabrata, Candida krusei, Candida tropicalis and Candida parapsilosis was reported in many parts of the world (Enwuru et al., 2008). The emergence of drug resistant yeasts, both genic and plasmid borne, reinforces the need to study further these pathogens and survey the susceptibility to drugs commonly used for therapy (Malar et al., 2012).

The azole drugs has been commonly used to treat many forms of candidal infections for a long time. However, their prolonged use selected drug resistance among C. albicans and other species. But resistance to the azole is more seen in non C. albicans spp. compared to C. albicans (Deorukhkar and Saini, 2013). Although several new antifungal drugs were licensed in recent years, antifungal drug resistance is becoming a major concern during treatment of such patients. The clinical consequences of the anti-fungal resistance can be seen either as treatment failure inpatients or as change in the prevalence of the Candida species causing infection. Antifungal resistance is particularly problematic since initial diagnosis of systemic fungal infection can be delayed and few antifungal drugs are available.

The treatments used against Candida infections vary substantially and are based on the anatomic location of the infection, the patients' underlying disease and immune status, the patients' risk factors for infection, the specific species of Candida responsible for infection, and, the susceptibility of the Candida species to specific antifungal drugs (Khan et al., 2015). So, it is of great importance to know the species of Candida responsible for the infection as well as its susceptibility patterns. In Cote d’Ivoire, few studies reported varying prevalence of vulvovaginal candidiasis (Konate et al., 2014; Djohan et al., 2012).

C. albicans is by far the most common species causing infections in humans (Djohan et al., 2012; Konate et al., 2014). Meanwhile, non-albicans Candida spp. were found to be emergent (Bonouman-Ira et al., 2011). There are few studies reporting yeast types identification and antifungal susceptibility using Fungus 3® with the drugs Amphotericin-B, Flucytosine, Fluconazole, Itraconazole and Voriconazole in Côte d’Ivoire. In addition, there is no National Surveillance Programme to monitor antifungal resistance among yeasts and other pathogenic fungi in Côte d’Ivoire.

The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of yeasts types and their antifungal susceptibility patterns of yeast isolates obtained from patients attending the Mycology Laboratory of Institut Pasteur of Côte d’Ivoire.

Study design

This study was a descriptive cross-sectional study conducted from January, 2011 to September, 2015 at the Mycology Laboratory of Institut Pasteur of Côte d’Ivoire. Patients from various hospitals of Abidjan were referred to the Mycology laboratory of Institut Pasteur of Côte d’Ivoire as a reference laboratory for mycological examination of various clinical samples. The informed consent was obtained from the patients. Samples of those who objected were not included in the study. Age, sex and clinical indication of mycology examination were noticed on the medical examination form delivered by the physician.

Samples such as nail scrapings, squama (from feet, back of hands, abdomen, legs, neck, arms), pus of ear and vaginal swab were collected under aseptic conditions in a sterile container and transported immediately to laboratory. Various clinical specimens were collected and processed as per the standard microbiological procedures. Vaginal swab samples were collected from female patients who complained about gynaecological problems such as vaginal discharge or vulvovaginitis and were referred to the laboratory for diagnostic purposes. Two vaginal swabs were taken by medical assistants one after the other by inserting a sterile vaginal speculum into the vagina, and then a sterile cotton wool swab was inserted into the posterior vaginal fornix and rotated gently before withdrawing. The swab was inserted back into the tube from which it was taken. The tube containing the swab was labelled with the patients study number, initials and date and then transported into the Stuart transport medium, to the laboratory.

Cultures of samples

The samples underwent a direct examination by wet mount preparation and Gram stain, inoculated on Sabouraud-Chloramphénicol (SC) and Sabouraud-Actidione-Chloramphénicol (SAC) media. The inoculated media were incubated at 37°C for 24 to 48 h; if no growth was observed, the incubation was extended up to 72 h. The isolates were considered significant if correlated with Gram staining, growth of two consecutive cultures, and the clinical presentation. The suspected Candida colonies were processed further for species identification.

Yeast identification

The reference procedures for identifying yeast species comprised germ tube production, micro-fermentation, microscopic morphology, chromogenic medium CandiSelect 4® (CS4; Bio-Rad) and Auxacolor 2® (Biorad) Tests.

Susceptibility testing

Anti-fungal susceptibility testing (Zhang et al., 2014) was done for 490 isolates of Candida by using ATB Fungus 3® of Biomérieux. This method enables to determine the susceptibility of the Candida isolates to the antifungal agents in a semi-solid medium following the conditions recommended by the European Committee on Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) and the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) (National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, 1997).

ATB Fungus 3® was performed following manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, ATB Fungus 3®of Biomérieux strip consists of 16 pairs of cupules including two growth control wells and five antifungal drugs at different concentrations: 5-Flucytosine (4, 16 µg/ml), Amphotericin B (0.5 to 16 µg/ml), Fluconazole (1 to 128 µg/ml), Itraconazole(0.125 to 4 µg/ml) and Voriconazole (0.06 to 8 µg/ml). The inoculated strips were used in duplicate (c and C) and were read visually after incubation at 37°C for 24 h. For each antifungal agent, the reading of the strips was started with the lowest concentration. The growth score was recorded for each of the wells and compared with the control wells as follows: No reduction in growth (4), slight reduction in growth (3), distinct reduction in growth (2), very weak growth (1) and no growth (0).

For Amphotericin B, the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the Candida species corresponded to its lowest concentration, thus enabling complete growth inhibition. For Fluconazole, Itraconazole and Voriconazole, as the possibility of a trailing growth existed, the MIC corresponded to the lowest concentration of the anti-fungal agent, with which a score of 2, 1 or 0 was obtained. For Flucytosine, a growth was looked for and was quantified in both the wells and tested for two concentrations. The results obtained gave an MIC that helps to classify the strain insensitive, intermediate or resistant. The anti-fungal breakpoints used followed the CLSI guidelines (National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, 1997).

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted within the ethical standards and approved by the Comite National d’Ethique de la Recherche of Côte d’Ivoire. Informed consent was obtained by participant prior their inclusion in the study.

Statistical analysis

Drug susceptibility testing was analyzed using WHONET 5.6. Data were analyzed with SPSS 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The prevalence of Candida species was reported in proportions. The relative frequencies of Candida susceptibility, determined by serology, were explored to look for differences between drugs (Chiâ€square test (χ2)). Fisher's exact test (at risk 5%) was used for comparison of proportions. Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 11.5 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois).

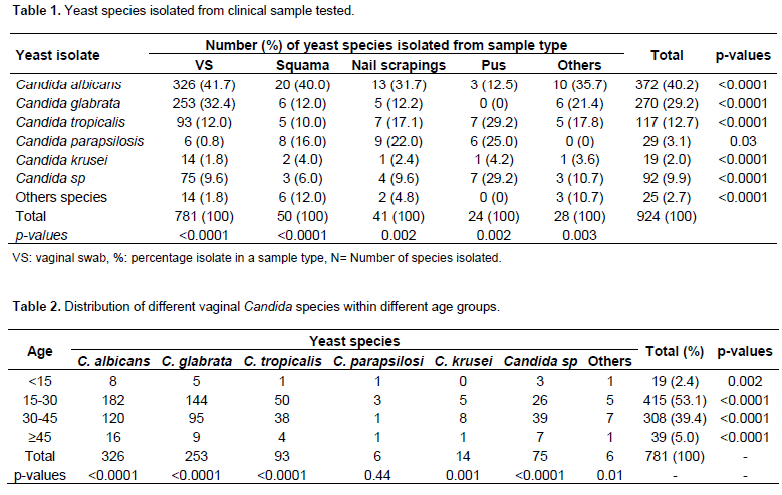

Table 1 show the clinical specimen wise distribution of Candida species. Most of the isolates were obtained from vaginal swabs 781 (84.5%), followed by squama 49 (5.67%). Overall C. albicans counting was 40.3% (372/924) of the infections, followed by C. glabrata (29.2%) and C. tropicalis (12.7%). Among the 781 vaginal yeast isolates, C. albicans was the most common species and identiï¬ed in 326 (41.7%) isolates, followed by C. glabrata in 253 (32.4%), Candida tropicalis in 96 (12.3%), and in 106 (13.6%), representing several species of Candida. The distribution of different species of vaginal Candida among the different age groups is shown in Table 2. The results obtained also showed that the 15 to 30 years group had the highest frequency of Candida species isolated (53.1%) followed by the 30 to 45 years group (39.4%). The age groups above 45 years (5%) and below 15 years (2.4%) had the lowest frequency of Candida. Statistical analysis of the data using one sample t- test indicates that there was significant difference in the prevalence among age groups (p-value = < 0.0001). The clinical patterns of vulvovaginitis Candida were dominated by leucorrhoea (35.7%) and pruritus (24.3%). The other functional signs were dyspareunia (17.3%), pelvic pain (12.9%) and dysuria (9.3%).

In the present study, antifungal susceptibility testing was performed for 490 Candida isolates. The results for the antifungal susceptibility test indicated that 96.8 and 96.3% of the vaginal yeast isolates were susceptible to amphotericin B and voriconazole with 3.2 and 2.9 resistant strains detected, respectively. Various resistant levels were detected against other antifungal drugs. Susceptibility levels to other drugs indicated that 67.7% of the yeasts were susceptible to flucytosine, 91.8% to fluconazole, and 86.6% to itraconazole. High proportion of resistance to Itarconazole were found with all of the Candida isolates tested. Intermediate category to flucytosine was shown by 58.8 and 30% of C. glabrata and tropicalis isolates, respectively. The details of the antifungal susceptibility test results are as shown in Table 3. The results of the antifungal susceptibility of the Candida yeast isolates from pus, squama and nails scraping against flucytosine, amphotericin B, fluconazole, itraconazole and voriconazole as determined by the ATB FUNGUS 3 test method are shown in Table 4.

In our study, itraconazole resistance was noted in 13 (11.8%) isolates and fluconazole resistance in 12 (10.9%) of them. Antifungal resistance was more common in C. albicans and C. tropicalis isolates.

Candidiasis is defined as infections caused by Candida species. It is considered as commensals in healthy individual and its capacity to produce superficial or systemic infections depends on the host immune system and various risk factors (Kauffman et al., 2011). In the present study, most of the yeast isolates were obtained from vaginal swabs. Clinical manifestations of vulvovaginitis are mainly featured by vaginal discharge and pruritus (Benchellal et al., 2011). Yeast infections of the vagina are common problems that cause significant morbidity and affect the well-being of women. Vaginal yeast prevalence among the patients is common as the organism easily colonizes mucous membranes (Moyes and Naglik, 2011) such as the vagina. In this current study, initial microscopy with wet film was used to assess whether there were just a few yeast cells, which may be considered a mere colonization. Also when large numbers of yeasts (more than 5 yeast cells per film) were seen with pseudohyphae then the diagnosis of yeast infection is established. The wet film ruled out Trichomonas vaginalis and Gram stain ruled out Neisseria gonorhoeae and Gardnerella vaginalis infections. In this work, C. albicans was the most frequently isolated species from vaginal swab followed by C. glabrata. However, it seems that non albicans species (C. glabrata and C. tropicalis) of Candida appear to be increasing (Salehei et al., 2012; Deorukhkar and Saini, 2013) as potential causes of vulvovaginal candidiasis . This increasing detection of non albicans species is probably related to the widespread and inappropriate use of antimycotic drugs used in the country.

In a study conducted by Konate et al. (2014), in 172 patients who suffered from vulvovaginal candidiasis, C. albicans was most frequently isolated (82.5%). It is worth noting that C. albicans is the most prevalent compared with other species, the reason probably being that it is a normal flora that takes advantage of risk factors such as pregnancy, antibiotic therapy, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, immunosupression due to HIV and others (Kiguli

et al., 2015 ; Gandhi et al., 2015).

C. albicans has a high pathogenic potential due to its high capacity to adhere to the vaginal mucosa as a result of the presence of Candida ligand vaginal cell inhibitors, thus allowing the manifestation of its virulence factors, germination and transformation from a saprophyte condition as blastospores, into a disease condition in a filamentous form (Anane et al., 2010). Highest frequency of Candida species isolated in 15 to 30 years age group could be a vulnerable group of candidal vulvovaginitis probably due to use of contraceptives and increased sexual activity. This results are supported by Abruquah (2012).

The in vitro susceptibility testing of antifungal agents is becoming increasingly important because of the introduction of new antifungal agents and the recovery of clinical isolates that exhibit inherent or developed resistance to Amphotericin B, Fluocytosine, and the azole group of drugs or Nystatin during chemotherapy. The sensitivity patterns of Candida isolates vary according to studies implemented in different countries (Adjapong et al., 2014; Feglo and Narkwa, 2012).

In this work, in vitro susceptibility of vaginal Candida species showed that the incidence of Fluconazole and Itraconazole resistance were higher than that of Flucytosine, Amphotericin B and Voriconazole. In addition, the decreased susceptibility to Fluconazole was most pronounced in C. albicans and C. glabrata, which was consistent with other studies (Diekema et al., 2012; Feglo and Narkwa, 2012). Fluconazole is one of the first-line antifungal drugs that are used in the treatment of infections due to Candida species other than Candidakrusei and some Candida glabrata isolates in Côte d’Ivoire.

In the country, Djohan et al. (2012) reported a C.albicans susceptibility of 100% to Amphotericin B; 98% to 5-Fluorocytosine; 86.7% to Voriconazole and 80% to fluconazole. Only 46.7% of C. albicans strains were sensitive to Itraconazole. Bonouman-Ira et al. (2011) found 65.6% of C. glabrata and 68.4% of C. tropicalis strains susceptible to Fluconazole. These differences in the country could be explained by antifungal susceptibility test, immunity of participants and different levels of exposure to antifungal drugs. Likewise, the Fluconazole susceptibility rate reported in the present study is high compared to those reported by Mondal et al. (2013) and Khan et al. (2015) who indicated 82 and 87.5% of respective susceptibility rate for Fluconazole.

Fluconazole (FCZ) is the first option for prophylaxis and treatment, due to its good tolerance, few side effects and low costs (Li et al., 2014). However, the widespread and prolonged use of antifungal agents induces tolerance development as well as collateral resistance to other drugs (Prasad and Rawal, 2014). Continuous exposure to azoles appears to have a major impact in selecting fluconazole-resistant Candida species. The finding of high proportion of C. glabrata and C. tropicalis isolates in the intermediate category of the sensitivity testing could be considered alarming: it is an indication for a potential selection for flucytosine resistant strains. In Côte d’Ivoire, antifungal drugs are sold over the counter, a practice which encourages self-medication and therefore may contribute to the development and spread of antifungal resistance. Also, the absence of rapid, simple, and inexpensive diagnostic tests continues to result in over diagnosis of vulvovaginal candidiasis with the consequence to extensive and inappropriate use of the drug. Physicians usually give empirical therapy and vaginal cultures are not routinely obtained, and susceptibility testing is rarely performed. Unfortunately, we did not assess usage of antifungal therapy in our patients.

Study showed that the Candida species from vaginal were less susceptible to the flucytosine than the azole drugs, likely because of the difference of mechanism between the azole and flucytosine drugs. The mode of action of azoles is less altered by Candida species compared to the polyenes drugs. Meanwhile flucytosine was found to be more susceptible to Candida species isolated from pus, squama and Nails scraping. The antifungal susceptibility levels reported are low in many countries (Pfaller et al., 2011), but the differences in susceptibility levels in these countries support the idea that the susceptibility of yeasts to antifungal drugs needs to be monitored.

Our study has limitations. First, risk factors for vulvovaginitis such as pregnancy, antibiotic therapy, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, immunosupression due to HIV and others were not assessed. Another limitation includes patients being restricted to those referred at the Mycology Unit of Institut Pasteur of Côte d’Ivoire. Therefore we cannot infer our data to the general population. Despite the limitations, the study provided baseline information on the identification of Candida species and their antifungal susceptibility in a reference laboratory in Côte d’Ivoire. The study buttresses the fact that most antifungals continue to be active against Candida strains from Côte d’Ivoire.

The present study showed that C. albicans was the most commonly isolated yeast from various clinical specimens. The results of antifungal susceptibility of drugs tested in this study support the use of these drugs when treating vulvovaginal candidiasis and others candida infections in Côte d’Ivoire. Meanwhile, a continuous monitoring is needed.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

We are grateful to all patients who participated in this study and the Department of Parasitology-Mycology for its support for conducting this work.

REFERENCES

|

Abruquah HH (2012). Prevalence and antifungal susceptibility of Candida species isolated from women attending a gynaecological clinic in Kumasi, Ghana. J. Sci. Technol. 32(2):39-45.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Adjapong G, Hale Mand, Garrill A (2014). An investigation of the distribution of Candida species in genitourinary candidiasis and pelvic inflammatory disease from three locations in Ghana. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 8(6):470-475.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Anane S, Kaouech E, Zouari B, Belhadj S, Kallel K, Chaker E 2010. Les candidoses vulvovaginales: facteurs de risque et particularitéscliniques et mycologiques. J. Mycol. Med. 20:36-41.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Arnold HM, MicekST, ShorrAF, Zilberberg MD, Labelle AJ, Kothari S, Kollef MH (2010). Hospital resource utilization and costs of inappropriate treatment of candidemia. Pharmacotherapy 30:361-368.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Benchellal M, Guelzim K, Lemkhente Z, Jamili H, Dehainy M, RahaliMoussaoui D, El Mellouki W, Sbai Idrissi K, Lmimouni B (2011). La candidose vulvovaginale à l'hôpital militaire d'instruction Mohammed V (Maroc). J. Mycol. Med. 21:106-112.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bonouman-Ira V, Angora E, Djohan V, Vanga-BossonH, Sylla-Thanon K, Beourou S, Toure AO, Faye-Ketté H, Dosso M, Koné M (2011). Profil de résistance des Candida non albicans à Abidjan en 2011. Rev. Bio-Afr. 9:27-31.

|

|

|

|

|

Deorukhkar SC, Saini S (2013). Vulvovaginal Candidiasis due to non albicans Candida: its species distribution and antifungal susceptibility profile. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2(12):323-328.

|

|

|

|

|

Diekema D, Arbefeville S, Boyken L, Kroeger J, Pfaller M (2012). The changing epidemiology of healthcare-associated candidemia over three decades. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 73:45-48.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Djohan V, Angora KE, Vanga-Bosson AH, Konaté A, Kassi FK, Yavo W, Kiki-Barro PC, Menan H, Koné M (2011).Sensibilité in vitro des souches de Candida albicans d'origine vaginale aux antifongiques à Abidjan (Côte d'Ivoire). J. Mycol. Med. 22:129-133.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Enwuru CA, Ogunledun A, Idika N, Enwuru NV, Ogbonna E, Aniedobe A, Adiega A (2008). Fluconazole resistant opportunistic oropharyngeal Candida and non-Candida yeast-like isolates from HIV infected patients attending ARV clinics in Lagos, Nigeria. Afr. Health Sci. 8:142-148.

|

|

|

|

|

Feglo PK, Narkwa P (2012). Prevalence and antifungal susceptibility patterns of yeast isolates at the Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital (KATH), Kumasi, Ghana. Br. J. Microbiol. Res. 2:10-22.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gandhi TN, Patel MG, Jain MR (2015). Antifungal susceptibility of candida against six antifungal drugs by disk diffusion method isolated from vulvovaginal candidiasis. Int. J. Cur. Res. Rev. 7(11):20-25.

|

|

|

|

|

Kauffman CA, Fisher JF, Sobel JD, Newman CA (2011). Candida Urinary Tract Infections-Diagnosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 52 (Suppl 6):S452-S456.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Khan PA, Fatima N, SarvarJahan N, Khan HM, Malik A (2015). Antifungal susceptibility pattern of candida Isolates from a tertiary care Hospital of North India: A Five Year Study. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 1:177-181.

|

|

|

|

|

Kiguli JM, Itabangi H, Atwine D, Kibuka LS, Bazira J, Byarugaba F (2015). Antifungal Susceptibility Patterns of Vulvovaginal Candida species among Women Attending Antenatal Clinic at Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital, South Western Uganda. Br. J. Microbiol. Res. 5(4):322-331.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Konate A, Yavo W, Kassi FK, Djohan V, Angora EK, Barro-Kiki PC, Bosson-Vanga H, Soro F, Menan EIH (2014). Aetiologies and contributing factors of vulvovaginal candidiasis in Abidjan (Cote d'Ivoire). J. Mycol. Med. 24:93-99.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Li H, Zhang C, Chen Z, Shi W, Sun S (2014). A promising approach of overcoming the intrinsic resistance of Candida krusei to fluconazole (FLC)-combining tacrolimus with FLC. FEMS Yeast Res. 14:808-811.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Malar ASS, Viswanathan T, Malarvizhi A, Lavanya V, Moorthy K (2012). Isolation, characterisation and antifungal susceptibility Pattern of Candida albicans and non albicans Candida from Integrated counseling and testing centre (ICTC) patients. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 6(31):6039-6048.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mondal S, Mondal A, Pal N, Banerjee P, Kumar S, Bhargava D (2013). Species distribution and in vitro antifungal susceptibilitypatterns of Candida. J. Inst. Med. 35(1):45-49.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Moyes DL, Naglik JR (2011). Mucosal immunity and Candida albicans infection. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2011:346307.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (1997).Reference Method for Broth dilution. Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts; Approved Standard. Document M27-A 17, 1/29

|

|

|

|

|

Pfaller MA, Andes D, Arendrup MC, Diekema DJ, Espinel-Ingroff A, Alexander BD, Brown SD, Chaturvedi V, Fowler CL, Ghannoum MA, Johnson EM, Knapp CC, Motyl MR, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Walsh TJ (2011). Clinical breakpoints for voriconazole and Candida spp. revisited: review of microbiologic, molecular, pharmacodynamic, and clinical data as they pertain to the development of speciesspecific interpretive criteria. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 3:330-343.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Prasad R, Rawal MK (2014). Efflux pump proteins in antifungal resistance. Front Pharmacol. 5:202.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Salehei Z, Seifi Z, Zarei A, Mahmoudabadi A (2012). Sensitivity of Vaginal Isolates of Candida to Eight Antifungal Drugs Isolated From Ahvaz, Iran. Jundishapur J. Microbiol. 5(4):574-577.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Zhang L, Wang H, Xiao M, Kudinha T, Mao L, Zhao HR, Kong F, Xu YC (2014). The Widely Used ATB FUNGUS 3 Automated Readings in China and Its Misleading High MICs of Candida spp. To Azoles: Challenges for Developing Countries' Clinical Microbiology Labs. PLoS ONE 9(12):e114004.

Crossref

|

|