ABSTRACT

Over the past two decades, migration in Africa has been rising continuously in all subregions. The range of migration flows include a rise in migrant workers, female migrants, an increase in irregular migration as well as a large number of refugees and internally displaced persons. It is no secret that current scholarship, especially the literature that concerned international organizations have adopted, has been unable to explicate the various dimensions of the phenomenon of migration and displacement in the context of Africa. Effective study of migration in Africa may require the "Africanization" of all related concepts to serve as a tool for analysis in accordance with a cultural pan-African perspective. This study seeks to explore the current transformations to the phenomenon of international migration in Africa, the most important factors driving it, and what policies and future challenges it faces. The paper uses a qualitative research design involving a literature review.

Key words: Migration, refugees, displaced persons, feminization of migration, environmental refugees.

In recent years, debates and public policies on migration and forced displacement have largely focused on the Mediterranean region and Europe (Beauchemin, 2015). Biased paradigms and narratives have resulted in a general disregard for migration and displacement issues in Africa, despite the fact that sub-Saharan Africa hosts the largest number of refugees, about 26% or more of the total refugee population in the world. Moreover, international migration routes in Africa are concentrated within the region, making the phenomenon of migration one of the major challenges facing the African states (United Nations Children’s Fund, 2019). Migration within Africa itself became in the last decade much more prevalent than migration from Africa to Europe or migration in other parts of the world (Whitaker, 2017; Ruyssen and Rayp, 2014; Bayar and Aral, 2019).

Review of the literature on migration and refugees underscores the urgent need to identify and analyze the regional, national, and internal conflicts that drive the forced migration of the continent's citizens, and the impact such events have on the life experiences of those Africans who have had to flee their homes (Ricca, 1990; Agadjanian, 2008). A full understanding requires exploring the effects of these conflicts, their spatial and physical forms, as well as the operations of refugees, internally displaced persons, and persons displaced by environmental factors. Migrants may establish a network of material and economic resources during their escape trips and after resettlement. Such resources are crucial to facilitating survival and sustainability in new refuge areas.

Forced migration requires forging new identities for refugees in urban areas, those residing in refugee camps, internally displaced persons, or refugees who have been resettled abroad. Studying issues of migration and refugees in Africa from an Africanity perspective serves to eliminate stereotypes of Africa as a continent of people living in perpetual tragedy, suffering from the ravages of war and famine, enduring endless refugee streams, and in need of assistance and charity. Forced migration is a global issue, and Africa is no exception (Danzinger, 2019). Africa as a diverse continent has become a showcase for how people, communities, and states deal with the immense human challenges posed by forced migration.

The extant literature, especially that which is adopted by consulted international organizations, is incapable of elucidating the myriad dimensions of migration and displacement in its African context. Indeed, even international law’s way of defining a refugee fails to capture the various dimensions of the phenomenon in its African reality. This may require the "Africanization" of these concepts so as to serve as a tool for analysis in accordance with an inclusive African civilizational perspective. This study seeks to explore the most important transformations witnessed by the phenomenon of international migration in Africa, the most important factors driving it, and what policies and future challenges? This paper considers that the qualitative approach has particular importance for forced migration studies, taking into account its ability to produce a rich and in-depth analysis. It also allows exploration of the complex and multi-faceted dimensions of migration dynamics. The data was collected from documentary materials such as journals, books and Internet sources. And with regard to data analysis, descriptive and analytical techniques were combined. Therefore, the discussion depended on systematic analysis and the use of tables and figures.

The study argues that Africa is a region of diverse circles of migration related to origin, destination, and transit. Migration in Africa is both voluntary and forced within and beyond national borders. Forced migration is fraught with controversial and sometimes contradictory interpretations. Voluntary migration is based on one's free will and initiative. It refers to migrants who leave their homes and reside elsewhere in search of economic opportunities such as employment, trade, and education. However, forced migration refers to people’s movement due to social and political problems such as armed conflict, human rights violations, and environmental disasters. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) has defined forced migration as “A migratory movement in which an element of coercion exists, including threats to life and livelihood, whether arising from natural or man-made causes (e.g., movements of refugees and internally displaced persons as well as people displaced by natural or environmental disasters, chemical or nuclear disasters, famine, or development projects)” (Ionesco, 2017, p. 130).

It is clear that the IOM definition of forced migrant comprises refugee and asylum seeker.In most cases forced migrants, commonly referred to as refugees, flee their places of residence for their physical security and to protect themselves from an imminent threat to their physical well-being. This paper aims to give more attention to African refugees who were forced to flee their homes and go elsewhere.

The paper has four parts. The first reviews the fundamental transformations in the migration phenomenon in Africa. Far from the traditional interpretations of African migration, which is mainly driven by poverty, violence and underdevelopment, the increase in migration rates from and within Africa seems to be driven by accelerated social and economic changes that have increased Africans' capacities and aspirations for migration, which has led to new trends in population mobility. The second part examines the main migration routes in Africa where four routes can be discussed according to the nature of the relationship between countries of origin and refuge. The third part provides an attempt to understand the phenomenon of migration in Africa more deeply. Finally, the fourth part discusses the evolution of African policies in the face of migration challenges and future impacts.

The bulk of international emigrants outside of Africa have gone to Europe (55%) and to Asia (26%), mostly the Arab Gulf States. While this inter-continental emigration is driven mostly by countries in Northern Africa, in both Eastern Africa and Western Africa migration is primarily contained within the region: Around 70% of migrants in each area stayed within the same region (United Nations Children's Fund. UNICEF, 2019).

TRENDS IN THE MAJOR TRANSFORMATIONS OF INTERNATIONAL MIGRATION

International migration in Africa is complex, highly interrelated, and involves many important transformations, the most notable of which is the transition from the concept of a traditional refugee to an environmental refugee and the feminization of migration. Despite the persistence of traditional waves of refugees and their multiple motivations and sources, smuggling and human trafficking complement this sad and complex picture of the international migration map in Africa. Wood (2019, 290-292) sets out a principled framework for interpreting and applying Africa’s expanded refugee definition. The framework goes beyond merely reciting the relevant international principles: it analyses their scope, applicability to Africa’s expanded refugee definition, and implications for the interpretation of the definition’s terms.

From traditional refugees to environmental refugees

When the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) arose in the aftermath of the Second World War, the term "refugee" included anyone who has been forced to flee his or her country because of persecution, war, or violence. A refugee has a well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group. Most likely, they cannot return home or are afraid to do so. War and ethnic, tribal, and religious violence are leading causes of refugees fleeing their countries.

However, this definition was found lacking as it excludes a range of other refugee situations. In response, Essam El-Hinnawi (1985) identified a new category of forced refugees, dubbed environmental refugees, which refers to people who flee from their places of origin for environmental reasons such as drought, earthquakes, or environmental degradation resulting from armed conflict, wars for natural resources, and so on. IOM defined environmental migrants as persons or groups of persons who, predominantly for reasons of sudden or progressive change in the environment that adversely affects their lives or living conditions, are obliged to leave their habitual homes, or choose to do so, either temporarily or permanently, and who move either within their country or abroad. (IOM, 2011, 33)

For environmental reasons, the issue of migration has become extremely important in sub-Saharan Africa. There are still unresolved issues and problems, particularly with regard to statistics and the reasons for such patterns of migration as well as with what policies are needed to address them. The literature on refugees in Africa before the 1980s failed to analyze the dynamics of the interplay among environmental, social, political and economic factors driving the waves of migration. In fact, some of the factors causing the phenomenon of migration cannot be isolated from the general context and the main actors (Epule, 2015).

Interestingly, the vast majority of environmental refugees come from the Sahel and the Sahara Desert region, which comprises some 17 African countries, from Senegal in West Africa to northern Eritrea in East Africa. Most of the population in this region suffers from threats associated with climate change. Political instability caused by civil wars, coups d'état, and lack of respect for human rights have also pushed people in rural and nomadic areas to cross national borders as a way of salvation and emancipation (Zoubir, 2012). In any case, about 70% of African migrants had to leave their homelands because of poverty and unemployment. Because about 64% of Africans and nearly 90% of Ethiopians depend specifically on agriculture for their livelihoods (Davis et al., 2017), the environmental variable becomes critical to knowing the new trends of migration in Africa.

The female face of international migration

General patterns of migration and refugees, both within and outside Africa, have been linked to the movement of men. That is, migrations have been seen as a purely masculine issue. Since the 1960s, gender has not been considered an important factor in understanding the drivers of international migration in Africa. However, recent trends point decisively to an increase in independent migration amongst African women. In Europe, only 39% of the refugee population was female in 2017, compared to 51% in Africa (UNHCR, 2018). African women migrate independently and the remittances that they send are necessary to family survival. While unfavorable economic conditions represent a common motivation for both men and women attempting to exit across national borders, women have other motives, such as searching for a more secure environment in terms of gender equality (Adepoju, 2004). Female migration in countries such as Zimbabwe, Uganda, Nigeria, and Mali show that female migrants are motivated by the desire to secure economic independence through self-employment or wage income (Adepoju, 1995). Furthermore, Gouws (2010) argued that as more women become educated, they migrate independently to support their own economic independence and to follow professional careers such as health care, for example.

There is no doubt that the feminization of the migration phenomenon has led to fundamental shifts in the roles of the African family in terms of the nature of the relationship between the sexes, a shift which has presented major challenges for public policymakers. For example, a large number of Burkinabe women flooded Ivory Coast in the pre-civil war period to work in the informal business sector, which is less affected by economic crises than the wage sector in which most migrant workers usually work. Along these lines, Adepoju (2008) has argued that professional women, both single and married, now engage in international migration. Married women leave their spouses behind with the children, who, in a reversal of responsibilities, are looked after by their fathers, or by other female members of the family. The remittances these women send home are a lifeline for family sustenance. This phenomenon of independent female migration constitutes an important change, and clearly can imply a turn-around in traditional gender roles, again creating new challenges for public policy.

Refugee workers and the phenomenon of xenophobia

The Ubuntu culture in traditional African thought calls for hospitality toward guests and welcoming strangers, which has made countries such as Uganda, Sudan, and Ethiopia the top of the list of countries receiving refugees. However, since the 1990s have demonstrated hostility towards foreigners in some African countries. The hate speech espoused by some politicians and opinion leaders in countries such as Ivory Coast, Libya, and South Africa has served to discriminate between citizens and foreigners. African refugees have been accused of spreading chronic disease or attempting to seize limited resources. There is no doubt that the situation of refugees and migrants is fraught with two-sided risks: persecution in their countries of origin, on one hand, and threats in the countries of refuge, on the other. Consider, for example, the refugee’s journey to South Africa, along which they must cross the Limpopo River in the summer and autumn at the peak of its flood. En route, survivors fall prey to gangsters who rob them of their money and rape their women (Adepoju, 2004).

The word ‘xenophobia’ derives from two Greek words, ‘xénos’, which means a person that looks different, a stranger, or a foreigner and ‘phóbos’ which means literally fear or horror. Thus, xenophobia is defined as perceived fear, hatred, or dislike of a non-native or foreigner in a particular country. In Africa, some of these manifestations date as far back as the 1960s. There have been many displays of xenophobia. For example, waves of terrorist attacks by the Somali al-Shabaab group incited negative reactions to Somali communities in Kenya (Oni and Okunade, 2018).

In South Africa, invectives against refugees revolve around one meaning: ‘Return to Your Country’, ‘South Africa is not yours’, and ‘You steal our works, our homes, our wives’. Refugees there struggle to access services such as banking and work permits, for which they are often required to pay a bribe to obtain or renew. They also suffer from lack access to appropriate accommodations because most owners refuse to accept the permits of refugees and asylum-seekers (Hassim, 2008).

The dialectic of migration and displacement

The major problem facing the international migration phenomenon in Africa resides in the nature of the relationship between migration and displacement, whereby sub-Saharan Africa hosts more displaced people than the number of persons who have migrated abroad. Internally displaced persons are persons or groups of persons who have been forced or obliged to flee or to leave their homes or places of habitual residence, in particular as a result of or in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict, situations of generalized violence, violations of human rights or natural or human-made disasters, and who have not crossed an internationally recognized state border” (Deng, 1999).

The above definition mentions some of the most common causes of involuntary movements, such as armed conflict, violence, human rights violations and disasters. In addition to that, such mobility takes place within national borders. There were about 18.4 million IDPs in sub-Saharan Africa in 2017, up sharply from 14.1 million in 2016, the largest regional increase of forcibly displaced people in the world. The Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly Zaire), Sudan, and Nigeria are among the African countries with the greatest concentrations of displaced persons. It is, indeed, striking that, in spite of an international convention concerning refugees that is more than half a century old and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the legal regime for the internal displacement of populations is much weaker.

The Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement are usually broadly defined as the predominant normative framework for IDPs. While these principles derive from international law, they are not binding in themselves. There is no specialized United Nations agency to address the needs of IDPs (despite progress made in recent years in assigning responsibility for IDP issues to relevant United Nations agencies); as such, it remains the responsibility of national governments to protect and assist IDPs within their own borders. Long-term displacement presents a stumbling block to finding sustainable solutions. For example, individuals often place land seizures on property left behind by the displaced, which makes the issue of land and property restitution complex, especially in cases where most people acquire land through customary law, as is the case in Africa. In Darfur, where nearly 2.4 million displaced persons live largely in camps which constitute difficult living environments, lack of security, education, and health services in indigenous communities complicate efforts to find durable solutions (OCHA, 2019).

Ubuntu philosophy could be interpreted as ‘‘a person is a person through other persons.’’ The actions that produce harmony, reduce discord, and develop community are simultaneously the actions that perfect one’s valuable nature as a social being. Nelson Mandela maintained that Ubuntu asserts that the common ground of our humanity is greater and more enduring than the differences that divide us. It is so, and it must be so, because we share the same fateful human condition. We are creatures of blood and bone, idealism and suffering (Lutz, 2009).

MAP OF MIGRANTS’ ROUTES IN AFRICA

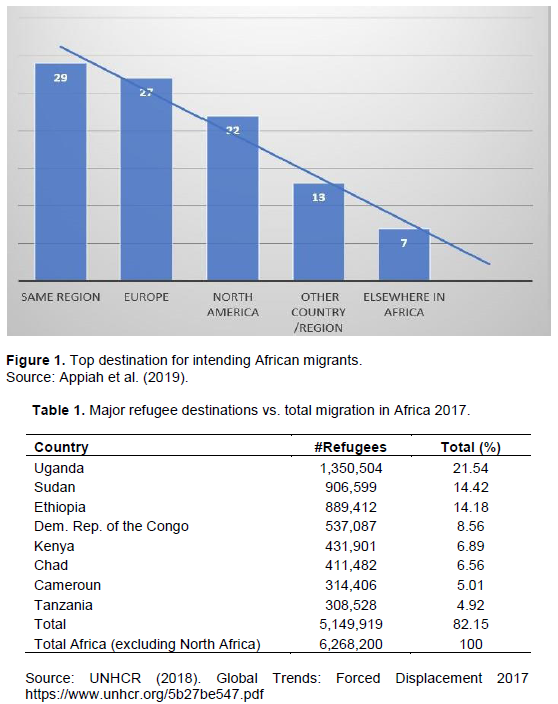

There are many signs that African migrants are more likely to move elsewhere within the continent than outside it. Figure 1 shows that 27% of Africans are more likely to move to another country within the same region in the continent. While migration to Europe via life-threatening journeys across the desert and the Mediterranean as well as to North America through immigration programs and asylum applications has dominated the headlines, Africans are more likely to migrate to another African country. A new Afro barometer survey of respondents in 34 African countries shows that 36% of Africans are more likely to move to another country within the continent.

Only 20% of African migrants who decide to migrate from their own countries are leaving the continent, according to the AU (Appiah, et al., 2019). For example, more people from the Horn of Africa move to Southern Africa than those who cross the North African desert to reach Europe (Figure 1).

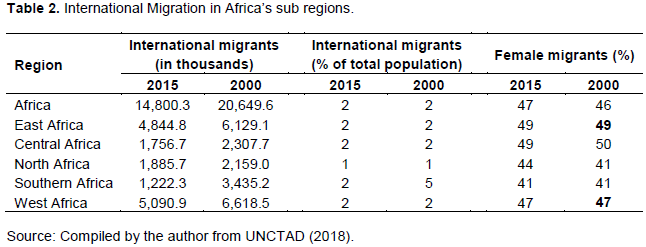

As Table 1 shows, the top eight destinations for refugees in Africa are Uganda (1,350,504), Sudan (906,599), Ethiopia (889,412), Democratic Republic of the Congo (537,087), Kenya (431,901), Chad (411,482), Cameroon (314,406), and Tanzania (308,528) which constitutes a total of 5,149,919 refugees of foreign origin (UNHCR, 2018). These refugees receive support and assistance in camps spread throughout these countries. The impact of the refugee crisis on each country varies according to the proportion of these figures to their total population. For example, Uganda provides support to a number of refugees, constituting a total of about 3.2% of the country's population. These ratios are also high in Chad, which hosts refugees representing about 2.9% of its total population. Sub-Saharan Africa, as the largest refugee region in the world, has 6.2 million refugees, compared to 3.4 million in Asia and the Pacific. The refugee population in East Africa increased dramatically during 2017, mainly due to the crisis in South Sudan, from which more than one million people fled, primarily to Sudan and Uganda.

Four major subregions of the phenomenon of immigration and displacement in Africa can be mapped out in terms of the dialectical relationship between countries of origin and host countries, as follows:

The Sahel-West African region

This region stretches from Mauritania and the Gulf of Guinea West to the shores of Eritrea East and represents the refugee crisis belt in Africa. Table 2 shows the volume of African migrants in absolute terms, and as a proportion of the total population in the region. There, some 20 million people suffer from frequent violent conflicts, volatile weather patterns, epidemics, and other calamities that are perpetuated by food insecurity and malnutrition. At the beginning of 2015, the region saw about 2.8 million IDPs. As the armed conflict in north-eastern Nigeria escalated at the hands of Boko Haram, an estimated one million people were forced to flee internally. Around 150,000 Nigerian refugees have managed to flee to neighboring countries such as Niger, Chad, and Cameroon. Unstable security in Northern Mali continues to be a source of instability for the lives of civilians, hampering the return of refugees (Vigil, 2017). Around 133,000 Malian refugees still live in Mauritania, Niger, and Burkina Faso, and more than 80,000 remain internally displaced. On the other hand, due to the ongoing crisis in the Lake Chad Basin, Chad has become the seventh largest refugee host country in the world, with more than 750,000 displaced persons, mostly refugees, and returnees who have fled from the Central African Republic, Libya, Nigeria, and Sudan.

The Horn of Africa

This region can be seen as a complement to what we might call the arc of crisis, with its extension in the great Sahel region, where armed conflicts have long led to the flight of millions of people for safety. One of the most striking of these wars and conflicts is the war between Ethiopia and Somalia for the control of the Ogaden region (1977-1978), the War of Eritrean Liberation, the civil war in the Sudan, the Eritrean Ethiopian conflict, and the civil war in Southern Sudan. Most of the refugees from these conflicts have been able to obtain shelter within the states of the same country as well as in neighboring countries such as Egypt and Kenya.

The Great Lakes region

Due to tribal factors and political conflicts in states such as Burundi, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Rwanda, the Great Lakes Region has become the epicenter of migration, with millions of refugees arriving over the past decades in the post-independence period. Most countries in the Great Lakes region have hosted these refugees, notably Tanzania, Uganda, and Kenya, as well as countries that are among the most popular country of origin and refuge at the same time such as the DRC.

Southern Africa

The countries of Southern Africa have received and continue to receive thousands of refugees forced to leave their countries due to struggles against colonialism, apartheid, and civil strife. Some countries, such as Mozambique and Angola, face a formidable challenge in dealing with hundreds of thousands of returnees, demobilized soldiers, and internally displaced persons. South Africa's experience points to another type of asylum: the phenomenon of refugees in urban areas.

TOWARDS A DEEPER UNDERSTANDING OF THE PHENOMENON OF MIGRATION IN AFRICA

Most scholars point to the tribal factor as the main cause of the refugee problem in Africa (Atim, 2013; Anthony, 1991). This view is based on the assumption that artificial boundaries inherited from the colonial era do not represent homogeneous regions inhabited by common ethnic or linguistic groups. In short, with decolonization, the different (traditionally conflicting) ethnic groups found themselves constrained by the geographical boundaries of the nation state inherited from the colonial era. The failure of national integration after independence meant there was almost no way for these groups to coexist peacefully. At the same time, some writers argue that ethnic identity is itself one of the main causes of the refugee problem in Africa. Some individuals are victimized and forced to migrate or to seek asylum simply because they have a different ethnic identity than those who exercise power in the state. One prominent example in the Great Lakes region is the bloody Hutu-Tutsi conflict, which has led to massive flows of refugees into neighboring states.

But the tendency of many analysts to posit cultural and racial differences as the leading causes of civil wars, political crises, and conflicts on the continent is flawed and misleading. This explanation casts blame on internal causes, which may themselves be symptoms of critical external roles and factors. Thus, the legacy of colonialism and the failure of post-independence nation states to manage certain aspects of their colonial legacies including the inability to absorb multiple forms of loyalties and affiliations within the state, has in turn, led to political instability, and even put the national state project itself to the test.

Independent African states have agreed to maintain the boundaries inherited from the colonial era by upholding the principle of ‘sanctity of colonial boundaries. As such, it is unacceptable to attempt to modify those limits by force. However, the continent has witnessed numerous separatist attempts in Biafra, Katanga, Eritrea, and the Ogaden, to name a few. There is no doubt that the situation in the Ogaden and South Sudan reflects the failure of both colonial powers and national governments to recognize the importance of demographic and ethnic factors in the delineation of national borders.

For example, Mamdani (2018) believes that the structural crises facing Africa are simply manifestations of the post-colonial crisis. Mamdani (2018) posited that structures of political instability and current conflict reside in the nature of the processes of formation and building of the colonial state, which eventually produced multiple political and ethnic identities.

One salient feature of the colonial system was ‘institutionalized discrimination’, which upheld a duality of laws (masters and slaves) and special legal regimes for different ethnic groups. Understanding this colonial context is undoubtedly necessary to grasping the current political crises in the region; however, it does not explain why most leaders, despite their knowledge of the weak foundation on which their inherited state was based, have tended to maintain systems that exploit resources and protect colonial interests rather than implement reforms which can address situations of inequality and maintain the diversity of ethnicities that shape the mosaic of new nations by recognizing the principle of equal citizenship.

War and civil strife are major causes of the refugee crisis in Africa. The past decade has seen a steady rise in violence across sub-Saharan Africa, such as Mali, South Sudan, Central Africa, and Somalia. Over time, the number of states experiencing armed conflict has doubled to 22. In the 1990s, some of these conflicts grew to be major regional wars, such as those in Liberia, Rwanda, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. The simmering tension between Ethiopia and Eritrea, which ended in a fierce war between the two states, also led to major waves of refugees and displacement. Such phenomena indicate that the post-Cold War era has not led to the realization of the dream of an African renaissance, as more than a quarter of sub-Saharan African countries have been left suffering from armed civil strife or regional tensions.

Many Africans have resorted to exile for environmental reasons, because the land in which they live is unfit for habitation or is no longer viable or arable. Not surprisingly, African countries affected by soil erosion, drought, and other environmental hazards are also in stages of armed conflict, recurrent famine, and refugee movement. The most notable examples are the states in the Sahel, the Sahara, and the Horn of Africa, and Mozambique.

As a whole, many of the causes of conflict and forced displacement in Africa, such as human rights violations, political power struggles, economic wealth, ethnic antagonism, and civil war, are symptomatic of deeper and more interconnected problems. In particular, we note the failure of most post-colonial leaders to reform the colonial state and reorganize power by establishing stable institutions that allow for the peaceful administration of power and the equitable distribution of social and economic opportunities and resources. In short, the ruling elite has failed to deal with the problem of citizenship and social justice.

Based on the foregoing discussion, it can be inferred that the migration of Africans cannot be attributed to a single factor; it is a very complex process in which ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factors interact. Figure 2 summarizes a variety of push and pulls factors. ‘Push’ factors mean that migrants are forced to move out of their homelands due to social, political, economic, environmental, and demographic drivers (Figure 2). In the case of ‘pull’ factors, migrants are attracted by opportunities in new locations. The effect of these factors differs from one individual to another, because the causes differ. People react to threats differently, to the extent that a mere rumor is enough to make some flee their homes.

CHANGES IN AFRICAN POLICY AND REFUGEE CHALLENGES

The emergence of the refugee protection system in Africa dates to the period of decolonization, with its increasing number of refugees and displaced persons. At the time, there was a need to address the inadequacy of the international refugee protection regime. Accordingly, African states established a complementary system for the protection of refugees which, over the years, has contributed to the development of new legal instruments, the analysis of which will respond to the question of whether an innovative African system for the protection of refugees is likely to have an effective impact on the development of sustainable solutions to this crisis (Nicolosi, 2014).

Three main stages of development of African policies and protection systems concerning refugees can be distinguished as follows:

(1) The first phase, stretching from the early 1960s to the end of the 1980s, is usually called the ‘open door policy’ stage. African states, individually and collectively, have adopted welcoming refugee situations within the framework of the 1969 Convention on Refugees adopted by the Organization of African Unity (Nyanduga, 2005; Oyelade, 2008). As Mwalimu Julius Nyerere put it: ‘We saw refugees coming out of colonial countries and our idea was, treat these people well’. African leaders never expected that, after independence, there would still be refugees and internally displaced persons (Okello, 2014). (2) The second phase covers the period from 1990 to 2001, during which the security risks and economic burdens of the asylum phenomenon increased, effectively ending the open-door policy. This shift is perhaps one of the most significant factors contributing to the increasing complexity and interrelatedness of the international asylum phenomenon in Africa. Moreover, the increase in transnational migration resulted in the expansion of relations between states of origin and states of refuge in the African context. The negative effects associated with the presence of refugee camps in host countries, such as the spread of crime, impact on the environment, and the depletion of limited resources, and have led many African States to refuse to accept refugees from other countries.

(3) The third phase comprises the years following the establishment of the African Union. Perhaps the fundamental turning point here was the union's call for member states to consider forced displacement to be a serious violation of human rights in security, peace, and dignity. This new orientation was enshrined in the Kigali Declaration on Human Rights in 2003. If the interest of the Organization of African Unity was primarily focused on the issue of asylum, the African Union addressed the issues of displacement and placed dealing with such issues at the forefront.

Despite a multiplicity of legal texts in the collective of African initiatives for the protection of refugees, there is the pressing issue of effectiveness (AU, 2018). A number of researchers are examining the usefulness of these initiatives and African countries’ ability to cope with these complex and multidimensional crises. For example, Nyanduga (2005) raised the issue of accountability for violations of refugee rights which is largely absent in African practice. Given the increasing numbers of asylum and displacement in many parts of Africa, the African legal system has been unable to provide adequate protection or a better life for refugees. At the international level, the refugee crisis in sub-Saharan Africa is receiving limited attention in international forums and organizations. Many host countries in the region have a weak or non-existent capacity to provide support to refugees. At the same time, international organizations entrusted with the management of humanitarian operations on the continent are experiencing a significant lack of resources.

These concerns have led to further challenges for both the states of origin and the states of asylum in terms of problems of political instability, civil strife, and low rates of economic growth, as in the Great Lakes region. One of the most significant challenges facing refugees in host countries is the lack of a secure environment within their camps and areas of residence; for example, hundreds of Hutu refugees in the DRC were killed by rebel groups. Jacobsen presented (1999) three reasons why refugee camps are more vulnerable to armed attack. First, the camps include some former combatant refugees, which make them a target by hostile forces both in the country of origin and in the country of refuge. Second, the camps can be seen as a repository, or warehouse, for recruiting exploited sexual and economic labor. Third, regional cross-border conflicts target refugee camps as part of the military strategy to weaken opposition morale or to commit ethnic cleansing.

Although the lives of refugees outside refugee camps are not always safe because they are targeted through armed attacks, their safety is also threatened by the residents of the host country. The influx of refugees into a socially and economically fragile environment poses a threat to the scarce resources of the poorer host nation population, and refugees are therefore targeted. As such, refugees become scapegoats for social problems and are relentlessly victimized by xenophobic measures, human rights violations, and negative images propagated by the media and opinion leaders in society (Palmary, 2004). One recent example presented itself in South Africa, where, since 2008, waves of xenophobic attacks have been perpetrated throughout the country, mostly towards

African refugees and asylum-seekers. Local residents often accuse refugees of stealing local jobs and of taking part in criminal acts. Unlike many countries, South Africa is seeing many refugees move into urban areas seeking access to basic services, such as housing, sanitation, and water, on an equal footing with South African citizens. This influx places an additional burden on local government and incites the dissemination of negative images of foreign refugees.

The issue of forced migration and displaced persons in Africa raises many concerns and problems, not only because of its humanitarian importance but also because of its impact on peace, security, and stability within Africa and the international security regime as a whole. Refugees in Africa are usually forced to flee their homes due to violence, armed conflict, and/or massive violations of human rights. The refugee problem, therefore, is essentially a man-made phenomenon. Issues stemming from conflict, displacement, and refugees in Africa are, to a large extent, intertwined with the crisis of citizenship. Extensive study has sought to elucidate the causes of these problems, including, as we have demonstrated, factors of race, colonial inheritance, the failure of the national elite to reform states inherited from the colonial era, human rights violations, and the logic of ‘sovereignty and State’. While these ideas shed some light on the causes of the problem, the substance of the matter includes the logic of ‘containment and exclusion.’ From this perspective, there is a dialectical relationship between civil public space and traditional space, which is based on primary affiliations, in other words a dialectical relationship between civic citizenship and ethnic citizenship, or a logic of sovereignty and the state. It is simply a manifestation of containment or the exclusion of others, a phenomenon that is very clear in the African context. For example, access to limited resources such as land and natural wealth is a motive for competition and exclusion.

It is clear that issues of race and land-related relationships have been used to legitimize particular tribal groups or delegitimize other groups to force them to settle at the margins of existing towns and villages (the most prominent example here is in the Great Lakes region). This struggle for access to and control over these resources has undoubtedly led conflicting ethnic groups to adopt harsh and violent positions. This complex migration crisis therefore cuts across many dimensions and dynamics.

The author has not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Appiah-Nyamekye J, Logan C, Gyimah-Boadi E (2019). 'In Search of opportunity: Young and Educated'. Afrobarometer Dispatch 288:1-32.

|

|

|

|

Adepoju A (1995). Migration in Africa: An Overview'.In: Baker, J. & Aina TA (Eds.), The Migration Experience in Africa, pp. 97-108. Uppsala: Nordiska Afrika institutet.

|

|

|

|

|

Adepoju A (2004). 'Trends in International Migration in and from Africa'. In: Taylor, D. S. (ed.) International Migration Prospects and Policies in a Global Market . London: Oxford University Press, pp. 59-76.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Adepoju A (2008). Introduction: Rethinking the Dynamics of Migration within, from and to Africa. In Adepoju, A. (ed). International Migration Within to and from Africa in a Globalized World. Ghana: Sub-Saharan Publishers.

|

|

|

|

|

Agadjanian V (2008). Research on International Migration within Sub-Saharan Africa: Foci, Approaches, and Challenges'. The Sociological Quarterly 49(3):407-421.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Anthony CG (1991). Africa's Refugee Crisis: State Building in Historical Perspective. The International Migration Review 25(3):574-591.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Atim G (2013). The Impact of Refugees on Conflicts in Africa. IOSR Journal of Humanities And Social Science 14(2):04-09.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

AU (2018). The Revised Migration Policy Framework for Africa and Plan of Action (2018-2027)'. (Addis Ababa: African Union; published online December 07, 2018.) Accessed 8 August 2019.

|

|

|

|

|

Bayar M, Aral MM (2019). An analysis of large-scale forced migration in Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16(21):4210.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Beauchemin C (2015). Migration Between Africa and Europe (MAFE): Looking beyond Immigration to Understand International Migration. Population (English Edition, 2002-) 70(1):7-11.

|

|

|

|

|

Danzinger R (2019).Confronting Migration Challenges in West and Central Africa. (Rwanda: The New Times; published online January 2019) accessed 14 May 2019.

|

|

|

|

|

Davis B. Di Giuseppe S, Zezza A (2017). Are African households (not) leaving agriculture? Patterns of Households Income Sources in Rural Sub-Saharan Africa. Food Policy 67:153-174.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Deng, F. M. (1999). Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement. International Migration Review 33(2):484-493.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

El-Hinnawi E (1985). Environmental Refugees'. Nairobi, Kenya: United Nations Environment Program.

|

|

|

|

|

Epule TE (2015). Environmental Refugees in sub-Saharan Africa: A Review of Perspectives on the trends, Causes, Challenges and Way Forward. Geojournal 80(1):79-92.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gouws A (2010). The feminization of Migration'. Africa Insight 40(1):169-179.

|

|

|

|

|

Hassim ST (2008). Go Home or Die Here: Violence, Xenophobia and the Re-invention of Difference in South Africa'. Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

IOM (2011). 'Glossary on Migration, 2nd Edition'. Geneva: International Organization for Migration (IOM).

|

|

|

|

|

Ionesco D, Mokhnacheva D, Gemenne F (2017). The Atlas of Environmental Migration. Routledge.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Jacobsen K (1999). A "Safety-First" Approach to Physical Protection in Refugee Camps'. Massachusetts: Inter-University Committee on International Migration

|

|

|

|

|

Lutz DW (2009). African Ubuntu Philosophy and Global management. Journal of Business Ethics 84(53):313-328.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mamdani M (2018). Citizen and subject: Contemporary Africa and the legacy of late colonialism' Princeton. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Nicolosi S (2014). The African union system of refugee protection: A champion not a recipient? International Organizations Law Review 11(2):318-344.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Nyanduga BT (2005). Refugee protection under the 1969 OAU Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa'. German Yearbook of International Law 47:85-104.

|

|

|

|

|

OCHA (2019). Sudan: Humanitarian Bulletin | Issue 05 | May- June 2019.

View. Accessed on January 02 ,2020.

|

|

|

|

|

Okello JO (2014). The 1969 OAU Convention and the Continuing Challenge for the African Union. Forced Migration Review 48:pp. 70-73.

|

|

|

|

|

Oni EO, Okunade S (2018). The Context of Xenophobia in Africa: Nigeria and South Africa in Comparison'. In: Akinola, A. O. (Ed.)The Political Economy of Xenophobia in Africa, pp. 37-51. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Oyelade O (2006). A Critique of The Rights Of Refugees Under The OAU Convention Governing The Specific Aspects Of Refugee Problems In Africa'. East African Journal of Peace and Human Rights 12(2):152-182.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Palmary I (2004). Refugees, Safety and Xenophobia in South African Cities: The Role of Local Government. Johannesburg. Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation, pp. 1-24.

|

|

|

|

|

Ricca S (1990). 'International Migration in Africa' Geneva: International Labor Office.

|

|

|

|

|

Ruyssen I, Rayp G (2014). Determinants of Intraregional Migration in sub-Saharan Africa 1980-2000. Journal of Development Studies 50(3):426-443.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

United Nations Commission on Human Rights (UNHCR) (1998). The Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, Addendum to the Report of the Representative of the Secretary General, Mr. Francis M. Deng, UN Doc. E/CN.4/1998/53/Add. 2.

|

|

|

|

|

UN Refuge Fund, UNHCR (2018). UNHCR Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2017. Geneva: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees; published online January 2019. Accessed 12 May 2019.

|

|

|

|

|

United Nations Children's Fund (2019). Data Snapshot of Migrant and Displaced Children in Africa' (New York: UNICEF; published online January 2019.) accessed 12 May 2019.

|

|

|

|

|

Vigil S (2017). Climate Change and Migration: Insights from the Sahel'. In: Carbone, G. (ed.) Out of Africa. Why People Migrate, pp. 53-72. Milano: Ledizioni Ledi Publishing.

|

|

|

|

|

Whitaker BE (2017). Migration within Africa and Beyond'. African Studies Review 60(2):209-220.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Wood T (2019). Who is a refugee in Africa? A Principled Framework for Interpreting and Applying Africa's Expanded Refugee Definition. International Journal of Refugee Law 31(2-3):290-320.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Zoubir YH (2012). The Sahara Sahel Quagmire: Regional and International Ramifications'. Mediterranean Politics 17(3):452-458.

Crossref

|

|