ABSTRACT

This article examines political trust in the institution of the presidency. It focuses on the Khama era and aims to find out the underlying motivations to trust the president. Using the Afrobarometer surveys, the paper finds that Batswana are more likely to distrust the president if they perceive high levels of corruption, poor government performance and are dissatisfied with democracy. Partisanship is important in trust for president and the most significant finding is that supporters of the Botswana Democratic Party have lost confidence in the president.

Key words: Botswana, political trust, institutions, presidency, attitudes.

Botswana’s political system is widely regarded as a Westminster parliamentary system but in reality it operates a fusion of parliamentary and presidential systems. The presidential candidate of a party that returns more Members of Parliament (MPs) stands duly elected as President. In applying the strict parlance of the parliamentary system such a candidate would be elected as prime minister. In the independence elections of 1965, Seretse Khama was elected as prime minister; the Constitution was amended later on that the head of government be called president. Although the president is not directly elected by the people, as is the case in presidential systems, the Constitution of Botswana empowers the office of the president with extensive executive powers. The president is not only the head of state and government, he is also Commander–in–Chief of the Armed Forces. The president is also adorned with wide ranging executive powers, as provided in section47 of the Constitution. Whilst recognizing the extensive executive powers the presidency enjoys in Botswana, this article seeks to establish the trust the president and institution are accorded by Batswana.

This article departs from the basic premise that political trust is an important “indicator of political legitimacy” and a functioning representative democracy (Turper and Aarts, 2015: 1) Various studies on political trust (Bratton and Gyimah-Boadi, 2016; Hutchison, 2011; Lavallée et al., 2008; Armah-Attoh et al., 2007) observe that lower levels of political trust lead to low levels of civic engagement and political participation. Studies in industrialized countries (Inglehart, 2007; Hetherington, 2005) and third world countries (Diamond, 2007; Armah-Attoh et al., 2007) observe a general trend in decline in trust in political institutions. An article by Seabo and Molefe (2017) on “The Determinants of Institutional Trust in Botswana’s Liberal Democracy” concludes that citizens’ underlying attitudes on corruption, satisfaction with democracy and the level of education are significant predictors of the likelihood to trust political institutions. This article seeks to contribute to the ongoing scholarly debate on political trust by focusing on Botswana’s executive presidency. A study of Botswana’s executive presidency is an important milestone in African politics because Botswana is considered Africa’s long serving multi-party democracy.

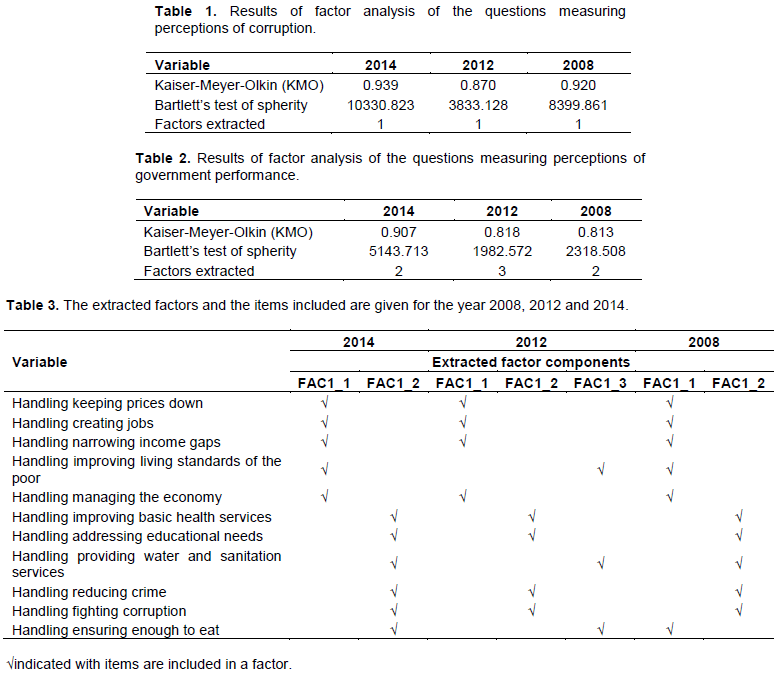

In using regression analysis, this article models trust in public institutions over an interval of three rounds of the Afrobarometer surveys conducted in 2008, 2012 and 2014. The findings of these surveys indicate that political trust has been on a decline in institutions of parliament, presidency and the ruling party. However, for purposes of this article, analysis will focus on declining trends in citizens’ trust in the institution of presidency during the era of President Ian Khama (Figure 2). Measurement of political trust during the presidency of Ian Khama is significant because he is not only the son of the founding president of the republic of Botswana but was also brought into politics as a panacea to revive the ruling party that was plagued by factional fights. Khama, having served an illustrious career in the military, being a paramount chief of the most populous ethnic group, Bangwato, was seen as a figure that would inspire political trust across the political divide, especially within the ruling party. In a more substantive way, this article postulates that declining trust in the presidency is explained by attitudes on democracy, corruption, economic performance and education.

The article is structured as follows; the first section provides the contextual framework of understanding the executive presidency in Botswana. Second, it delves into a theoretical framework that explains the basis for political trust. This article draws heavily from the social capital theory, which explains interpersonal trust and political trust. Third, the methodology explains the dependent and independent variables that are used to measure political trust in the executive presidency. Fourth, it presents the findings and analysis of results, which are followed by conclusions. This article proceeds to address trust in the presidency, first by proving the political and economic context of understanding the executive presidency in Botswana.

Before independence Bechuanaland, as Botswana was called then, together with the other High Commission Territories of Basutholand and Swaziland, were considered “economic hostages of South Africa” (Halpern, 1965) and there was a strong lobby to incorporate them into the Union of South Africa. Such incorporation was highly resisted given that South Africa was a pariah state based on racial discrimination and domination. At independence in 1966, Botswana had to overcome all odds; of not only being one of the poorest countries in the world but also of creating a viable state in a region dominated by white settler colonialism and racial dictatorships. Botswana defied the odds to become the longest serving multi-party democracy in Africa (Holm and ad Molutsi, 1989) and also an economic success story (Samatar, 1999).

At independence, the dominant economic activity in the country was farming, especially livestock farming. Although this sector was destabilized by periodic droughts, it remained the mainstay of the economy and was a means of livelihood for Batswana. The advent of the borehole technology in the 1950s that led to the sinking of boreholes in the hinterland opened more areas for cattle farming (Peters, 1984). The establishment of the Botswana Meat Commission (BMC) in 1954 made cattle farming a lucrative industry and facilitated the emergence of a cattle owning class drawn from the traditional Tswana aristocracy comprising of chiefs, sub-chiefs and headmen (Tsie, 1996).

After independence, the technocratic-bureaucratic approach of a non-partisan civil service guided national development planning and defined the path of capital accumulation (Parson, 1983). The basic thrust of government policy was rural development that cultivated a strong link between the State, the cattle owning class and the rural peasantry. Arising from government programs and subsidies, there was a convergence of interests between the ruling elite (mostly farmers and small businessmen) and the rural peasantry (Parsons, 1981; Peters, 1984; Picard, 1980). They developed programmes that assisted the livestock sector. Besides, President Seretse Khama, Quett Masire and a significant numbers of Cabinet Ministers and Members of Parliament were renowned cattle farmers. Civil servants who were not allowed by their conditions of service to operate businesses could engage in farming, as it was considered a traditional and cultural undertaking. As a result, the interests of the ruling Botswana Democratic Party (BDP) support by a strong bureaucratic arm were congruent with those of the cattle owning elite and the rural peasantry. To use the analogy of Gramsci (1971) and Poulantzas (1968), the cattle owning elite was the hegemonic fraction of the ruling class. One would extrapolate that the synergy between the political and economic elite would generate high levels of political trust. This assertion would be supported by the fact that during those years, the BDP was returned to power every election period by overwhelming majorities.

After the discovery and exploitation of minerals, Botswana experienced an unprecedented growth where in some instances she surpassed the East Asian Tigers. Botswana’s development trajectory changed when cattle receded as the mainstay of the economy, and gave way to minerals, especially diamonds. As a result of the “new wealth” (Parsons, 1983) accrued from diamonds, new power relations emerged in Botswana’s political economy. Unlike cattle farming that was largely based on national capital, even though the BMC sold beef to the European Union, the influence of international capital on the local market was negligible. It was diamond mining through Debswana, which is a partnership between De Beers and Botswana government, that Botswana got immersed into the dictates of international capital. It is in the public domain that De Beers played a significant role in facilitating the smooth retirement of President Masire in 1989.

Diamonds transformed Botswana from being one of the poorest countries in the world at independence like Bangladesh to become an economic success story (Leith, 2000). Today, according to Manatsha and Maharjan (as cited in Sebudubudu and Botlhomilwe, 2012: 116). Botswana is classified as an Upper Middle Income country, with a GDP per capita of US$ 17,779 … It is the largest producer of diamonds by value in the whole world. It is also ranked the top least corrupt countries and investor friendly by the World Bank.

On the political front, the country has been described as a shining example of democracy for consistently conducting regular free and relatively fair elections. This is despite the fact that only a single party, the BDP, has dominated elections and there has yet to be an alternation of power. Albeit with a decreasing popular vote, the BDP’s electoral success has in part been due to a polarized and fragmented opposition.

Although Botswana smart partnership with De Beers was able to get good returns from diamonds and accrue substantial foreign reserves, this did not leverage the economy in international capital markets. Instead, the country depended more on a single export commodity, which made it extremely vulnerable to global financial markets, as was experienced in the 2008 global financial meltdown. Even though the Diamond Trading Company (DTC) has been relocated from London to Gaborone, diamond trade is still dominated by external sight holders. The external linkages of the Botswana economy are further strengthened by the tourism industry, which is largely foreign owned and dominated. The industry is dominated by Wilderness Safari that is largely owned by foreign investors. As a result, the weak linkages between the tourism industry and the domestic market mean that it marginally contributes to sustainable economic development. Even though it is projected as an alternative engine of economic growth, in a situation where about 70% of the proceeds are remitted outside the country, it contributes very little to micro economic stability. Moreover, the low volume high cost nature of the industry makes it an elite enclave that is patronized by a national and foreign elite. Ordinary Batswana have a limited stake in it.

Since Khama ascended to the presidency there has been a significant shift in power relations within the BDP, and the distribution of power between the state and the people. Khama’s presidency has had an impact on the already declining popularity of the BDP and Botswana’s democratic credentials. Co-opted into politics from the military, Ian Khama was tipped as a possible unifying factor in the deeply factionalized BDP that was facing a concerted challenge from the opposition. Perhaps his biggest undoing was the historic split of the party he was roped into politics to safe from self-destruction. Until 2010, the BDP was a stable political outfit that had survived harsh political torrents since its establishment in 1962, outcompeting opposition parties in every election and consolidating uninterrupted state power. Its dominance is well documented and has been attributed to the “First Past the Post Electoral System” (Molomo, 2000a;b), “fragmentation of the party system, and obstacles to strategic voting behavior” (Poteete, 2012: 75); lack of organizational capability and inadequate financial resources (Osei-Hwedie 2001); and opposition’s internal stability (Maundeni and Lotshwao, 2012). Although the BDP’s popularity had been waning even before the advent of Khama, the supposed savior of the party led it to destruction through his sheer disdain for dissent and criticism. For instance, ‘in early 2010, following a bitterly contested BDP congress election in 2009, in which President Khama’s preferred candidates lost, a faction that had stood against his preferred candidates complained of its members being “systematically persecuted and marginalized” (Makgala and Botlhomilwe, 2017: 15).

Moreover, under Khama, democratic gains have been reversed, as instanced by onslaught on media freedoms, judicial independence and extra judicial killings. For instance, as Good (2016: 12) wrote, “Khama is known for his strong aversion for meeting the press in unscripted, open conference.” In 2009, Freedom House downgraded Botswana’s political rights rating as a result of “decreased transparency and accountability in the executive branch under President Seretse Khama Ian Khama’s administration” (Freedom House, 2015a). The extrajudicial killing of John Kalafatis in 2009 by security agencies was a severe blow to Botswana’s democratic credentials. Irrespective of the circumstances that led to his demise, in a democracy the rule of the law should always be the norm.

It is perhaps under the presidency of Ian Khama that it is fitting to describe Botswana according to Good’s (1996) assertion that it is an authoritarian liberal state where there is an erosion of the country’s democratic probity and people experience shrinking political space. A characteristic feature of Khama’s presidency is that he adopted a militaristic approach of rule through decrees and directives, undermining governance through consultation and consensus. Taking over the reign of power from Festus Mogae in 2008, Khama exercised executive power enshrined in the constitution (see section 47 of Botswana Constitution on executive powers) to the fullest extent. ‘General Khama’s more overt autocracy was founded upon established presidential power’ (Good, 2016: 5). For De Jager and Sebudubudu (2016: 9), “Botswana has a towering or domineering executive that dwarfs all the other institutions”. Democratic consolidation in Botswana requires strong institutions and not strongmen. Instead of building institutions, president Khama swallowed institutions. For instance, during the 2011 industrial strike instead of allowing the Bargaining Council to conclude negotiations between government and labour unions respecting salary increases, President Khama unilaterally told a Kgotla meeting that he would not accede to salary increases (Molomo, 2014: 167). The intransigence of the BDP government led to an unprecedented industrial strike lasting eight weeks resulting in collusion between opposition parties and Botswana Federation of Public Sector Unions (BOFEPUSU) calling for regime change.

In his personalized rule, drawing from military discipline and personal authority deriving from traditional authority, he personifies himself as the embodiment of democratic rule. Moreover, Khama embraced populist politics by centralizing political and distributive power around himself and his office. Khama’s leadership style presents an interesting paradox of frugal spending on others but opulence and luxury when it comes to him; his retirement package that entitles him to boats and aircrafts tells the story. In what would characterize him as a “benevolent despot”, he endears himself to the less privileged through various humanitarian gestures, charity work, distributes hampers, blankets and radios. A noble gesture given the needs of the poor but two questions arise from it. First, are these gestures sustainable? Second, do they have the potential to lift people out of poverty? A further comment on these gestures is that they colour the political landscape and lead to political patronage.

In a paternalistic fashion, he prefers to engage with a submissive, uncritical and less inquisitive constituency in rural areas, especially by sitting around the fire with old men - Kenneth Good, (2016) calls it ‘bonfire democracy’. Another notable feature of Khama’s presidency is that instead of interacting with his peers at fora such as the African Union (AU) and United Nations (UN), he would rather attend a conservation meeting in some corner of the globe. The autocracy that characterized the Khama administration has rendered service delivery very weak. Characteristic of Khama’s personalized rule, programmes are not considered government programmes but mananeo a ga rraetsho (the President’s programmes). These are programmes, include among others, backyard gardens, poverty eradication programmes and the presidents housing appeal. So, when these programmes fail, like backyard gardens, the presidency has failed. Political trust is enhanced when institutions function and deliver on their mandate of providing goods and services. Political trust is further eroded when there are intrigues and machinations in the political system.

Unfolding events in Botswana’s political landscape are complex and checkered, they border on intrigue and political manipulation. The most recent autocratic gesture by former president Khama is the bid to have an indirect third term despite having stepped-down as state president. In an unprecedented manner, Khama has been operating behind the scenes by influencing the outcomes of the Botswana Democratic Party primary elections. In his usual intrigues, as a military strategist and political schemer, the former president seeks to have control of BDP candidates for the 2019 elections in order to protect and entrench the political influence of the Khama dynasty. Worst still, Khama is using the tribal card to lure voters in the Central district where he is paramount chief to maintain hegemonic influence in the party and government. More disturbing are allegations in the media of attempts to preempt the judicial process bent on prosecuting people around him on allegations of corruption and money laundering (Sunday Standard, 2018; The Botswana gazette, 2018)

However, the most significant development during the Khama era is the convergence of interests between big business, the military and the ruling elite. Since Khama assumed the presidency in 2008, there has been a significant increase in the number of military personnel in positions normally performed by civilians. When Khama took the presidency as a retired army general, his vice President was a former commander Lt Gen Mompati Merafe, whom Khama deputized when he was in the army. Some retired military generals made it into partisan politics and others into diplomatic postings. However, some few retired brigadiers and Generals have also joined the ranks of the opposition. The high spending in the military as evidenced by the much debated intend to spend 16 billion dollars in buying Grippon Jet fighters shows a strong congruence between the military and the political elite.

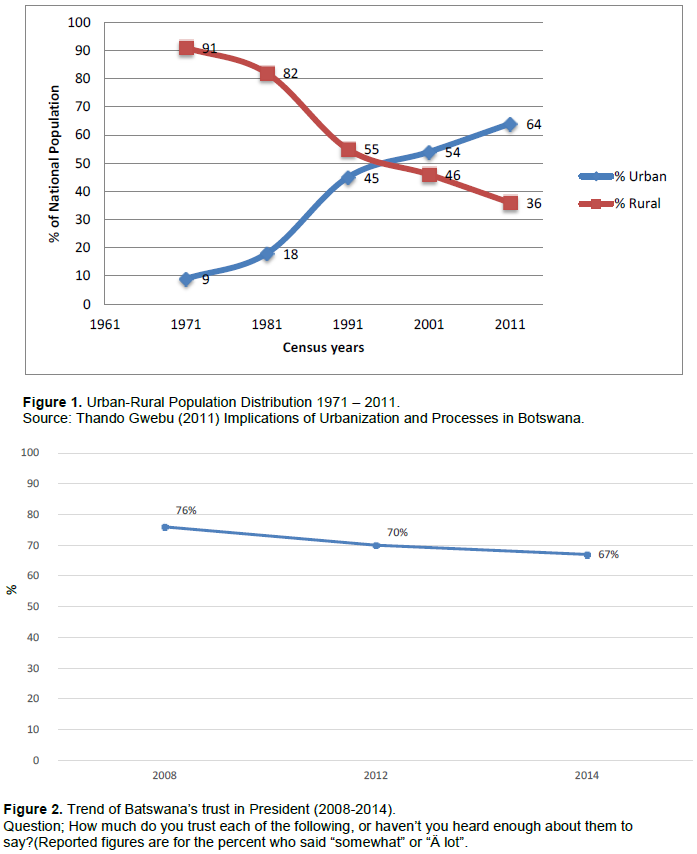

President Khama took over the reigns of power in 2008, when the performance of the economy was at its lowest. However, other factors could explain the waning political trust in Botswana’s political institutions, in particular the presidency. First, there are changing population demographics that do not favour the ruling BDP. It is a known fact that the BDP support base is in the rural areas, and now as a result of urbanization and population movements, 64% of the population lives in urban and peri-urban areas. Figure 1 shows that since the mid-1990s the profile of the Botswana voter has changed dramatically; more and more people resided in urban and per-urban areas thus thinning the BDP’ support base. Urbanization has not only exposed workers to the perils of a wage economy but has also mobilized them into unions that engage in collective bargaining for better wages and working conditions. The collective bargaining process has pitted government against labour unions. The unprecedented civil servants strike of 2011 that lasted for 8 weeks that cost the country millions of pula in terms of lost production is a case in point. Through this tussel, the BDP government alienated professional and workers. All this changed the electoral fortunes of the BDP and the unrelenting posture of President Khama exposed his military style of leadership. Second, Botswana faces a dilemma of a bulging youth population that is disenchanted by high levels of unemployment. Figures from Statistics Botswana indicate that unemployment stands at 17.8%. This disenchantment partly accounts for the reduced poll of the BDP in the 2014 elections. Moreover the media, especially the private media, plays an important watch-dog function in a democracy. With the advent of the private media, which is more critical of government procedures and processes, leaders are scrutinized to be more transparent and accountable. The level of public scrutiny has intensified with the proliferation of social media. All these factors do not favour the BDP as the ruling party, and Khama as party and state president could not escape negative appraisal on the performance of government and the economy.

. Headlines in the Sunday Standard read 26 August 2018 – 01 September 2018 “Kgosi to be Charged in two weeks”; “Khama implicated in Kgosi’s alleged corruption”; “Kgosi employs scorched earth tactics against Magosi”; “ Former president likely to be called in as witness”’ “Kalafatis’ ghost haunts campaign to prosecute Kgosi” ; “DCEC impounded Kebonang and Kadiwa’s vehicles in money laundering case” . And headlines in the The Botswana Gazette 29 August – 04 september 2018 read: “And the winner is…A Khama victory that could split BDP”; “Masisi faces Khama back push”; “Khama invokes tribal loyalty to gain support”; “Khama has the support to sustain Vote of no Confidence in BDP Government”; “ Where to next? BDP at Crossroads”; “ The culmination of Bulela ditswe has widened the rift between Masisi and Khama”.

In the run-up to the October 2014 elections, three opposition political parties, namely the Botswana National Front (BNF), Botswana Peoples Party (BPP) and the Botswana Movement for Democracy (BMD) coalesced into the Umbrella for Democratic Change (UDC). The Botswana Congress Party (BCP) was the only opposition party that did not join the umbrella. Out of the 57 seats that were contested, the UDC won seventeen (17) seats making a combined poll of the opposition 20 seats. Clearly, more than any other election year, the opposition was within striking distance to capturing state power. The 2014 elections were a reflection of the situation in the country and should not be taken as a fluke that could be corrected by introducing cosmetic changes. They were a reflection of deep seated fundamental demographic, social, political and economic changes in Botswana. The BDP government, especially the leadership, is seen by many in the new middle class, the youth and working class as non-responsive to their plight, needs and aspirations.

According to the Independent Electoral Commission (2014) election report, a head count during the 2014 elections shows that the BDP polled a total of 320 647 votes whilst its closest rival the UDC got 207 113 votes. By every account, an overall margin of 113 534 votes is significant and a comfortable win. However, if when disaggregating the data and focusing on specific constituencies, a different picture emerges. Overall, 16 constituencies could be said to be marginally won, that is by a margin of less than 500 votes. 11 of these were won by the BDP and 5 by the combined opposition. The BDP victory in the 2014 elections was based on a margin of only 2 538 votes.

The decline on the levels of trust is not just a random occurrence; it is a result of underlying socio-economic challenges and political realities in the country. More fundamentally, this decline comes at a time when the incumbent government of the long time ruling BDP is grappling with growing citizen disaffection over ‘bread and butter’ issues as well as a dwindling popularity and a resurgent opposition that threatens to dislodge it from power in 2019. Besides, during the period under review, there were notable and unprecedented political dynamics such as the historic split of the BDP, a nationwide industrial strike and deterioration of media freedoms. Also significant is the BDP’s worst showing at the 2014 general elections in which the party emerged as a minority government in the face of a resurgent opposition collective.

The decline in the ability of government to deliver on political goods leads to the erosion of trust between the people and government, especially the presidency. The distributive politics that characterized earlier regimes is no more. In the past, civil servants knew that they benefitted handsomely on salaries review. During the Khama administration, the power of collective bargaining was eroded and civil servants suffered erosion of their earnings from inflation let alone the rising standard of living. Botswana being one of the most unequal economies in the region means that poverty is a factor that influences people’s perception against the presidency. In the past, government could spend itself out of political trouble, now with a reduced national cake every spending is an opportunity cost, and government is often constrained on public spending.

Botswana has failed to broaden the economic base. In the past farmers were sure of their sales to the BMC. Now BMC, which is a cooperative of farmers, does not only face the threat of being privatized by a tiny white cattle owning elite, it is no longer a cash cow it was historically acclaimed to be. It is a big setback that the BMC, which was established in 1954, is still faltering and not diversified to take advantage of the many livestock by-products. Government has not succeeded to broaden the economic base, the economy is essentially government-driven, and governments are well-known for their inefficiency in service delivery. In the past few years, Botswana has suffered severe erosion compounded by power and water shortages. The narrow economic base where the state is the main investor, employer and distributor for economic goods makes contestation for political power a matter of life and death. Political intrigues and posturing have become the order of the day. Political parties, mainly the BDP, as the party in government, appear to be captured by business interests. The award of tenders and procurements need further scrutiny and research in light of allegation of impropriety that damage the good name of the country. The misappropriation of the National Petroleum funds going into millions, which is before the courts and the linkages arising from it is likely to expose acts of corruption, which could make accolades that Botswana is the least corrupt country in Sub-Saharan Africa by the World Bank misplaced. The next section focuses on the theoretical framework that underscores the theoretical foundation of political trust.

.These are Ngami, 48; Francistown East, 245; Bobonong, 120; Selebi Phikwe East, 242; Boteti West241, Gaborone South, 243; Takatokwane, 130; Kanye North, 72; Kgalagadi North, 238; Nata Gweta 470; and Lobatse.

.Mogoditshane, 334; Gabane-Mankgodi, 322; Molepolole South, 387; Kanye South, 361; Ghanzi North and 314.

Often measured in public perception surveys, trust is a fundamental component of mass beliefs on a wide array of issues including performance of public officials, state and political institutions alike. Welzel and Inglehart (2003) argue that mass beliefs are thus the intervening variable between social structure and collective action and ignoring this, democratization processes cannot be adequately understood. Harold Lasswell (as cited in Welzel and Inglehart, 2008) posits that whether democratic regimes emerge and survive largely depends on mass beliefs. Studies in trust have become increasingly important in recent years due to the significance of trust in the development of societies. Simmel (as cited in Delhey and Newton, 2003: 93) states that trust was “one of the most important synthetic forces within society”. This is because trust forms the basis of understanding society in terms of social capital, extent of civic engagement and even more fundamentally the way people perceive their political system and leaders. The origins of trust may be located at two levels, the social level and the institutional level. Trust stems from personal predispositions and concrete experiences of trustworthiness in social interaction as well as experience and evaluation of a situation and performance (Freitag and Traunmüller, 2009). At a social level, for people to cooperate through social groups, societies or clubs, trust is the basis of which such cooperation can be achieved.

On the political sphere, trust emerges from people’s expectations that political representatives as well as institutions would perform insofar as service delivery is concerned. But more importantly this paper deals with political trust on institutions as opposed to social or interpersonal trust which is built on social relations.

Trust is an abstract and broad term that to date no theory best explains why and how people tend to trust others in society. As a result attempts to explain trust have yielded different interpretations and meanings from which to understand why people trust, first other people, leadership and institutions. Generally trust is thought of as faith or confidence that people in a community or society have towards one another or towards leaders and institutions. In this sense, Newton (2001) distinguishes between social trust in society and political trust which relates to the political realm particularly political leaders and institutions. Both early life socialization and contemporary performance evaluations influence levels of trust (Mishler and Rose, 1997). Trust is a form of a relationship that is based on a conviction that a trustee would not fail the client in a transaction. Studies have shown that for societies to achieve their collective goals in the process of development, governments need citizens to have trust in their public institutions (Landmark, 2016). More fundamentally, institutional trust is an essential ingredient of democracy because democracy functions when among other factors citizens have trust in public institutions (Harold Lasswell, 1951, Christensen and Lægreid, 2005; Bratton and Gymah-Boadi, 2016). Newton (2001) writes that political trust is related to political capital just as much as social capital is related to social trust and both are key to the functioning of democracy. A trustworthy government and public institutions are vital for the development and sustenance of a democracy and guarantees an engaged and involved citizenry. The result is increased legitimacy of government and a more obedient populace. Newton (2001) points out that political trust is essential for democratic and stable political life. The net effect of institutional trust is increased legitimacy for a government as citizens feel that their needs are addressed (Jamil and Askvik, 2015).

Cultural and institutional approaches have so far been reliable and used widely in the literature of trust. Cultural theories put emphasis on social norms and societal beliefs that are acquired early in life through socialization. These norms and beliefs are the basis for social trust at the level of a community but they are assumed to later extend to trust in institutions. According to Mishler and Rose (2001), cultural theories hypothesize that trust in political institutions is exogenous, meaning that it starts from outside political institutions and is a result of long standing cultural norms that are learned through the process of socialization and later projected unto political institutions. Social and cultural trust is a more generalized form of trust in the social sphere (Newton, 2001), which implies that it is built among individual peers, neighbors and social groups. Mishler and Rose (2001) aptly posit that cultural theories emphasize the importance and durability of pre-political or early-life socialization reflecting individuals’ experiences with kin, peer group, and community. The classic view is that a society that is well founded upon a large and varied range of voluntary associations and organizations is likely to generate high levels of social trust (Delhey and Newton, 2003:5)

On the other hand, trust in institutions is performance-based, implying that institutions are evaluated on the extent to which they meet expectations and preferences of people. This is in line with Mishler and Rose’s argument that political trust is a consequence of institutional performance which is evaluated on both the economic and political dimensions (2001). People trust institutions based on their assessment or evaluation of how well they deliver on their mandate or promises made. The assumption is that people are rational when they evaluate political institutions and determine whether they trust them or not based on their performance in areas of economic growth, corruption, democracy, civic participation and access to social amenities. As noted before, institutional trust gives legitimacy to political institutions and the absence of trust breeds disaffection with institutions or the political system. Institutional trust is generated when institutions deliver upon promises made. It is the simple campaign promises and ethical expectations of professional conduct upon which a decision to trust institutions of parliament, presidency, courts of law and parties is made. Failure by government to create employment, fight corruption, and deliver services such as health care and education risks withdrawal of support by people. Rational choice thinking suggests that trust is likely to be high for institutions that perform well but when institutions are perceived not to perform in accordance with what is expected of them, trust level is likely to drop.

Hypotheses

Political trust can be directed towards the political system and its organizations as well as the individual political incumbents (Blind, 2006). Political trust happens when citizens appraise the government and its institutions, policy-making in general and/or the individual political leaders as promise-keeping, efficient, fair and honest (ibid). Political trust can be measured by looking at a number of variables including political interest, civic engagement, voter turn-out, tax payment, participation, political tolerance and confidence in the President, Parliament and other public institutions (Newton, 2001).

Trust is related to attitudes on democracy, where low levels of satisfaction with democracy would result in low trust and high contentment with democracy leads to high trust levels. Seligson et al. (2002) observe that studies found that a public’s trust in the actors and institutions of political authority facilitates democratic consolidation in that institutionally-trusting individuals have been found to be more supportive of democratic principles. Accordingly, trust in government generally increases according to the level of satisfaction with democracy, importance of politics in life, interest in politics, membership of political parties and affiliation with the left end of the political spectrum (Christensen and Lægreid, 2005). Norris (1999) is of the view that if people do not trust institutions, they would not trust the way democracy works as a whole and ultimately be disillusioned with democracy as an ideal.

Botswana’s democracy under the leadership of president Khama has come under a spotlight as a result of his authoritarian style of leadership, circumventing established institutions and using directives. Under the Khama regime, private media has had to operate in an environment that is not free and incidents of journalists’ arrests have become commonplace in Botswana’s democracy. In 2015, Freedom House downgraded Botswana’s rating from completely free to partial free while the 2016 Mo Ibrahim Index of Governance listed Botswana as one of the top ten that have deteriorated along with Ghana and South Africa.

H1: We expect low attitudes on satisfaction with democracy to decrease trust in the presidency.

Moreover, perceptions on corruption are related to institutional trust because corruption affects institutional performance. Uslaner (2003) maintains that the most corrupt countries have the least trusting citizens. Citizens of countries with high levels of corruption place less value on political institutions and are less confident in their political system (Anderson and Tverdova, 2003). If individuals perceive corruption in politics, then their trust in institutions gets adversely affected Job (2005). Blind (2006) discusses two essential considerations on the relationship between corruption and trust and political legitimacy. The first consideration is that according to Warren (as cited in Blind, 2006), public officials do not have to just fight corruption but they should also not appear to be involved in it. Secondly, people can still trust government (and leaders) even when there is perceived corruption for so long as bonds of trust established through social capital are strong. Though corruption in Botswana has not been as pervasive as in other African countries, in the recent past there have been allegations of misuse of public funds involving the construction of an airport strip in the president’s private property and construction of retirement home at tax payer’s expense. In recent years, however, the country’s CPI score has declined (Transparency International, 2015) and while these developments may not in the main have tarnished Botswana’s reputation as a least corrupt African country, there are likely effects on the confidence of people towards leaders. Makgala and Botlhomilwe (2017:8) remind us that “while elite corruption persists in Botswana, at a much reduced scale when compared to other African countries, a 2014 Afrobarometer survey demonstrated a sudden upsurge in Batswana’s perception of corruption in government.” The same survey revealed that a majority (81%) of Batswana think that government officials are involved in corruption and 70% of Batswana think the president and officials in his office are involved in corruption (ibid).

H2: We expect negative attitudes on corruption in the presidency to decrease trust in the presidency.

Institutions are trusted or distrusted to the extent that they produce desired economic outcomes. (Mishler and Rose, 2001). Following the performance based theory, people lose confidence on institutions that do not meet their needs and whose performance is evaluated negatively. Geert Bouckaert and Steven Van de Walle (2001:3) state that “performance theory has a number of aspects: what should government do according to citizens, how does the concept of ‘government’ figure in citizen’s minds, and how correct are the perceptions of performance? This applies to both micro-performance (service delivery) and macro-performance (economic situation, unemployment…).” But more fundamentally, how well government delivers basic amenities such as water, health care, infrastructural developments and employment is important in the generation of institutional trust.

Essentially, as asserted by Blind (2006:17) “increasing social and political trust through the implementation of sound economic policies is also crucial for good and effective governance”. Nevertheless, the perception that a government “does not function for [the citizens]” is associated with distrust (Miller, 1974: 951). As noted elsewhere in the article, under Khama the standard of government performance in service delivery in terms of creation of employment opportunities and provision of basic amenities such as portable water has dropped. The downward trend in government effectiveness is attributed to the deterioration of the quality of public services, of the civil service, of government policies and implementation capacity (Deléchat, and Geartner, 2008). The government’s effectiveness is currently below the standards of upper-middle income countries which Botswana is part of. Good (1999:50) argues that Botswana’s political system is characterized by “elitism, centralized political power and weak executive accountability”. In an earlier formulation he had said that the political elite are “accountable to themselves” (Good, 1999: 5-47).

H3: We expect negative attitudes on government performance to decrease the likelihood to trust the president.

Sample surveys are the conventional social-science method for obtaining data about opinions, attitudes and behaviour of objects. Sample surveys can and do ask individuals to report their perceptions of trust in political institutions. In this paper we analyse 4th round (2008), 5th round (2012) and 6th round (2014) of the Afrobarometer surveys conducted in Botswana to test the above hypotheses. In each of these surveys, a cross-sectional nationally representative sample of 1200 Batswana of voting age was interviewed.

The model of what explains trust in the presidency stipulates that the likelihood of a person doing so is a function of their spatial location, their evaluation of government performance, satisfaction with political system, social inclusion or exclusion, and perceived corruption. The level of analysis will be individual Batswana who are of voting age, that is, Batswana who are at least 18 years of age.

Regression analysis

The theoretical hypotheses set out above can be linked in a simple model. The Afrobarometer surveys use the measurement; “How much do you trust each of the following, or haven’t you heard enough about them to say?” The scale for this measurement is the likert scale; “0=Not at all”, “1=Just a little”, “2=somewhat”, “3=A lot”, “9=don’t know/ haven’t heard”.

Regression analysis is a form of predictive modelling technique which investigates the relationship between a dependent (variable of interest) and independent variable(s) or explanatory variable(s). Regression analysis estimates the relationship between two or more variables. The dependent variable trust in political institution was re-coded into a binary one (Appendix Table 1). A binary logistic regression model was therefore fitted to the data. Agresti (2002) defined logistic regression as a method which models the relationship between a set of independent variable Xi (can either be dichotomous, categorical or continuous) and the dichotomous dependent variable Y. This variable Y has a Bernoulli distribution and can be denoted by:

where

is the intercept parameter and

is the vector of slope parameters.

The quantity to the left of the equal sign is called a logit. It is the log of the odds that an event occurs (the odds that an event occurs is the ratio of the number of people who experience the event to the number of people who do not). This is what one gets when they divide the probability that the event occurs by the probability that the event does not occur, since both probabilities have the same denominator and it cancels, leaving the number of events divided by the number of non-events). The coefficients in the logistic regression model tell you how much the logit changes based on the values of the predictor variables.

To fit a binary logistic regression model, you estimate a set of regression coefficients that predict the probability of the outcome of interest. Logistic regression modeling has applications in many areas, including clinical studies, epidemiology, data mining, social sciences, marketing, and engineering. It has proved to be reliable for both prospective analyzes (such as designed experiments or clinical trials) and retrospective analyzes (such as found data or case-control studies). If your response variable can take only two values (the event and the non-event), then the conditions for linear regression are not met; in particular, your errors are binary and not normally distributed. Binary logistic regression was developed to handle this case. Instead of modeling the response itself, you use logistic regression to model the probabilities of events.

To examine the reliability of the questions on corruption and government performance as measuring a latent variable, factor analysis was also conducted, whereas Cronbach’s alpha (αCr > 0.6) was used as a criterion for the reliability of the extracted factors. Cronbach’s alpha is a statistic which is generally used as a measure of internal consistency or reliability of a psychometric instrument. In other words, it measures how well a set of variables or items measures a single, one-dimensional latent aspect of individuals. Factor analysis of the variable measuring perceptions of corruptions (Q53a-j for round 6; Q65a-k for round 5 and Q57a-k for round 4) was used to extract factors. Table 1 shows that only one factor was extracted for perceptions of corruption in the three surveys. A measure of the reliability gave a Cronbach’s alpha greater than 0.6. A measure of the reliability of the items measuring a latent variable ‘corruption’, gave a Cronbach’s alpha close to one which implies reliability. Cronbach's alpha determines the internal consistency or average correlation of items in a survey instrument to gauge its reliability. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was recorded as well as the Bartlett’s test of spherity. The KMO statistic is close to 1 whilst test of spherity is highly significant.

Factor analysis of variable measuring government delivery (Q66a-m for round 6; Q60a-f for round 5 and Q50a-h for round 4) was used on government delivery resulted in a two-dimensional factor solution in 2014 and 2008 whilst in 2012 we obtained 3 factors. A measure of the reliability of gave a Cronbach’s alpha greater than 0.6. The factors extracted from the analysis can be summarised as a factor covering the provision of basic necessities like water, improving basic health services, addressing education needs etc. The other factor can be generalised to cover managing the economy such as creating jobs, keeping prices down etc. A summary of the results of the factor analysis are given in Table 2. The KMO measure of sampling adequacy is close to one whilst the Bartlett’s test of spherity gave a chi-square value which is highly significant suggesting that the R-matrix is not an identity matrix.

In Table 3 the extracted factors and the items included are given for the year 2008, 2012 and 2014. The two extracted factors in 2008 and 2014 could be classified as measuring provision of necessities (bread and butter issues with exception of the last item which is ‘handling ensuring enough to eat) or micro-level issues (FAC1_1). In 2008 however, this item of handling ensuring enough to eat is included in the necessities factor. The second factor could be thought of as a macro-level issue measuring overall management of the economy.

In 2012 however, three factors are extracted. The first and second factors still measures provision of necessities and overall management of economy, respectively. The third factor is made up of handling improving living standard of the poor; providing water and sanitation services and ensuring enough to eat. On the surface of it, these are bread and butter issues and essential human needs that it is not surprising for them to be lumped into a similar category.

Perception of trust in the president

Prior to fitting a logistic model to predict the likelihood to trust the president shows that gender, an evaluation of the significance of the independent variables was carried out. The residual chi-square statistic is highly significant at p=0.000 (labelled Overall Statistics) for the years under consideration. This statistics shows that the coefficients for the variables not in the model are significantly different from zero; in other words, that the addition of one or more of these variables to the model will significantly affect its predictive power. The remainder of the results in this table lists each of the predictors in turn with a value of Roa’s efficient score statistics for each one (column labelled Score). In large samples when the null hypothesis is true, the score statistics is identical to the Wald statistics and the likelihood ratio statistic. It is used at this stage of the analysis because it is computationally less intensive than the Wald statistic. Roa’s score statistic has a specific distribution from which statistical significance can be obtained.

The binary logistic regression model of trust in the president in Table 4 shows that the education variable was a significant factor in explaining the likelihood to trust in the president in 2014. Individuals with higher levels of education are much more likely to trust the president than individuals with no education. However, the odds ratios are much higher for individuals with lower level of education in hence lending support to the hypothesis that more educated are less likely to trust than the less educated.

Perceived corruption in the country is not a significant factor in predicting likelihood to trust the president in 2008 and 2012. However, in 2014 this is a highly significant factor (p-value=0.011). This is not a coincidence because of the increased perceived corruption in the country particularly in state institutions. Similarly, in 2014 majority (51%) of Batswana believed that corruption has increased over the past year (Molomo et al, 2015). Perhaps even more denting on Botswana is the fact that Transparency International’ s Corruption Perception Indices indicate that public sector corruption is on the rise. According to Diepo (2014) in 2012 Botswana scored 65%, dropped to 64% in 2013 and further declined to 63% in 2014.

Social inclusion variables like location, gender, age and civic engagement are not significant factors in the models, indicating that the level of trust is not dependent on these demographic variables. Government’s handling of important matters (two factors) for 2008 and 2014 and three factors in 2012; satisfactions with democracy are highly significant explanatory variables in predicting the likelihood to trust the president. The first factor on government performance; FAC1_2 (provision of basic necessities) is highly significant in predicting likelihood to trust in the president for all the years. The second factor on government performance, FAC2_2 (managing the economy) is highly significant factor in predicting the likelihood to trust the president in 2008 and 2014 only. The third factor on government performance (FAC3_1) in 2012 is highly significant factor (p-value<0.01).

Respondents were asked if they feel close to any particular political party. This variable ‘closeness to a political party’ is a highly significant factor (p<0.01) for all the years under consideration with an odds ratio of 2.921 which is greater than 1 in 2008. This implies that respondents who identify themselves as being close to the ruling party are almost three times more likely to trust the president than respondents who identify with the opposition. In 2012 and 2014 however, the odds ratios are less than 1. This implies that respondents who identify themselves as being close to the ruling party are less likely to trust the president than respondents who identify with the opposition. This is quite a striking finding, which begs the question whether BDP supporters have lost confidence in the president. The BDP under Khama has indeed been rocked by instability to a point where the party experienced an unprecedented split in 2010.

In spite of his seeming unifying attributes for which Khama was roped into politics, the trust in the presidency under his reign is on the wane. This article has found that attitudes on corruption, government performance and democracy underlie political trust in the presidency of Ian Khama. Trust in the president is also a function of one’s party identification and BDP followers have increasingly become distrustful of the president. These results do not come as a surprise, given the events characterizing the presidency of Ian Khama, the highlight of which was the historic split of the BDP.

However these results should be taken with caution in generalizing them beyond Botswana because of contextual differences with other countries. Nonetheless, it can be postulated that elsewhere views on increasing corruption, dissatisfaction with democracy and poor government performance can affect institutional trust. Theoretically, the implication of these results is that mass beliefs have become important considerations even in dominant party systems such as Botswana.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Agresti A (2002). Categorical Data Analysis, Second Edition. Canada: John Wileys and Sons, Inc.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Anderson C, Tverdova Y (2003). Corruption, Political Allegiances, and Attitudes Toward Government In Contemporary Democracies', American Journal of Political Science 47(1):91-109.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Armah–Attoh D, Gyimah-Boadi E, Chikwanha AB (2007). Corruptio and Institutional Trust In Africa: ImplicationsFor Democratic Development', New York, NY: Afrobarometer.

|

|

|

|

|

Blind PK (2006). In Fricker RD, Kulzy W, Combs DJ (2013). 'Modeling Trust in Government: Empirically Assessing the Integrative Model of Organizational Trust'

|

|

|

|

|

Bouckaert G, Van de Walle S (2001). Government performance and trust in government. In Ponencia presentada en la Annual Conference of the European Group on Public Administration, Vaasa (Finlandia).

|

|

|

|

|

Bratton M, Gymah-Boadi E (2016). 'Do Trustworthy Institutions Matter For Development? Corruption, Trust, and Government Performance in Africa.

|

|

|

|

|

Christensen T, Lægreid P (2005). Trust in government: The relative importance of service satisfaction, political factors, and demography. Public Performance & Management Review 28(4):487-511.

|

|

|

|

|

De Jager N, Du Toit P (2012). Friend or Foe? Dominant party systems in southern Africa. Cape Town: UCT Press.

|

|

|

|

|

Deléchat C, Gaertner M (2008). Exchange rate assessment in a resource-dependent economy: the case of Botswana (No. 2008-2083). International Monetary Fund.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Delhey J, Newton K 2003). Who trusts?: The origins of social trust in seven societies. European Societies 5(2):93-137.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Diamond L (2007). Building trust in government by improving governance. In 7th Global Forum on Reinventing Government: "Building Trust in Government" Sponsored by the United Nations Session V: Elections, Parliament, and Citizen Trust Vienna.

|

|

|

|

|

Diepo T (2014). Transparency International: Botswana least corrupt …But public sector corruption on the rise.

View

|

|

|

|

|

Freedom House. (2015a). Botswana. Available at:

View.

|

|

|

|

|

Freitag M, Traunmüller R (2009). Spheres of trust: An empirical analysis of the foundations of particularised and generalised trust. European Journal of Political Research 48(6):782-803.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Good K (1996). Authoritarian Liberalism: A defining Characteristic of Botswana. Journal of Contemporary African Studies 14(1):29-51.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Good K (1999). Enduring elite democracy in Botswana. Democratization 6(1):50-66.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Good K (2016). Democracy and development in Botswana. Journal of Contemporary African Studies 35(1):113-128.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gramsci A (1971). Selections from the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci: Ed. and Transl. by Quintin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell Smith. International Publishers.

|

|

|

|

|

Gwebu T (2011). Implications of Urbanization and Processes in Botswana", (ed) Rolang Majelantle.

|

|

|

|

|

Halpern J (1965). South Africa's Hostages: Basutoland, Bechuanaland and Swaziland (Vol. 8). Penguin Books.

|

|

|

|

|

Hetherington MJ (2005). Why trust matters: Declining political trust and the demise of American liberalism. Princeton University Press.

|

|

|

|

|

Holm J, ad Molutsi P (1989). Democracy in Botswana. Gaborone. Macmillian Press.

|

|

|

|

|

Hutchison ML (2011). Territorial threat, mobilization, and political participation in Africa. Conflict Management Peace Science 28(3):183-208.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Independent Electoral Commission (2014) Report to the Minister for Presidential Affairs and Public Administration on the 2014 General Elections. Gaborone: Government Printer.

|

|

|

|

|

Inglehart R, Welzel C (2003). Political culture and democracy: Analyzing crosslevel linkages.

|

|

|

|

|

Jamil I, Askvik S (2015). Citizens' Trust in Public and Political Institutions in Bangladesh and Nepal. In: Governance in South, Southeast, and East Asia pp. 157-173). Springer International Publishing.

|

|

|

|

|

Job J (2005). 'How is Trust in Government Created? It Begins At Home, But Ends in The Parliament', Australian Review of Public Affairs 6(1):1-23.

|

|

|

|

|

Landmark M (2016). Trust in public institutions, a comparative study of Botswana and Tanzania (Master's thesis, The University of Bergen).

|

|

|

|

|

Lavallée E, Razafindrakoto M, Roubaud F (2008). Corruption and trust in political institutions in sub-Saharan Africa. Afrobarometer.

|

|

|

|

|

Leftwich A (1996). Democracy and Development: Theory and Practice. Oxford: Polity Press.

|

|

|

|

|

Leith C (2005). Why Botswana Prospered? Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press.

|

|

|

|

|

Makgala CJ, Botlhomilwe MZ (2017). Elite interests and political participation in Botswana, 1966–2014. Journal of Contemporary African Studies 35(1):54-72.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Maundeni Z, Lotshwao K (2012). Internal organisation of political parties in Botswana. Global Journal of Human-Social Science Research 12(9).

|

|

|

|

|

Miller AH (1974). Political Issues and Trust in Government: 1964–1970', American Political Science Review 68(03):951-972.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mishler W, Rose R (1997). Trust, distrust and skepticism: Popular evaluations of civil and political institutions in post-communist societies. The Journal of Politics 59(2):418-451.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mo Ibrahim (2015). The 2015 Ibrahim Index of Governance.

View

|

|

|

|

|

Molomo MG (2000a). Democracy Under Seige: The Presidency and Executive Powers in Botswana," Pula: Botswana Journal of African Studies 14(1) pp 95-108. Molomo MG (2000b). In Search of an Alternative Electoral System for Botswana," Pula: Botswana Journal of African Studies 14(1):109-121.

|

|

|

|

|

Molomo MG (2001). Civil-Military relations in Botswana's Developmental State," Africa Studies Quarterly (the online Journal of African studies) http:/www.africa.ufl.edu/asq/.

|

|

|

|

|

Newton K (2001). Trust, Social Capital, Civil Society, and Democracy', International Political Science Review 22(2):201-214.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Norris P (1999). Critical Citizens: Global Support For Democratic Government', Oxford University.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Osei-Hwedie BZ (2001). The political opposition in Botswana: The politics of factionalism and fragmentation. Transformation P.45.

|

|

|

|

|

Parsons J (1983). The trajectory of class and state in dependent development: the Consequences of new wealth for Botswana. Journal of Commonwealth Comparative Politics 21(3):39-60.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Parsons J (1981). Cattle, Class and state in Rural Botswana," Journal of Southern African Studies 7(2):236-255. Peters P (1984). Struggle over Water, Struggle Over Meaning: Cattle, Water and the State in Botswana" Africa: Journal of international African Institute 54(3):29-49.

|

|

|

|

|

Picard LA (1980). Bureaucrats, cattle, and public policy: Land tenure changes in Botswana. Comparative Political Studies 13(3):313-356.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Poteete AR (2012). Electoral competition, factionalism, and persistent party dominance in Botswana. The Journal of Modern African Studies 50(1):75-102.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Poulantzas N (1968). Political power and Social Classes. London: NLB and Shhed and Ward.

|

|

|

|

|

Samatar AI (1999). An African miracle: State and class leadership and colonial legacy in Botswana development. Heinemann Educational Books.

|

|

|

|

|

Seabo B, Molefe W (2017). The determinants of institutional trust in Botswana's liberal democracy. African Journal of Political Science and International Relations 11(3):36-49.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sebudubudu D, Botlhomilwe MZ (2013). Interrogating the Dominant Party System in Botswana. Friend or Foe pp. 115-131.

|

|

|

|

|

Seligson M, Mitchell A, Julio A, Carrión F (2002). Political support, political skepticism, and political stability in new democracies: An empirical examination of mass support for coups d'etat in Peru. Comparative Political Studies 35(1):58-82.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Transparency International (2015). Corruption Perceptions Index.

|

|

|

|

|

Tsie B (1996). The political context of Botswana's development performance." Journal of Southern African Studies 22(4):599-616.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Turper S, Aarts K (2015). Political Trust and Sophistication: Taking

|

|

|

|

|

Uslaner EM (2003). Trust, democracy and governance: Can government policies influence generalized trust?." Generating social capital. Palgrave Macmillan, New York pp. 171-190.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Welzel C, Inglehart R (2009). Political culture, mass beliefs, and value change. Democratization pp.126-144.

|

|