Full Length Research Paper

ABSTRACT

This paper outlines the origin, meaning and benefits of Transitional Justice (TJ). It looks at the various mechanisms or processes used to implement transitional justice. The paper also re-assessed transitional justice in Southern African states with focus on South Africa, Mozambique, and Angola. The historical background to transitional justice in these countries is given then their various TJ mechanisms examined. These portray the strengths and shortcomings of TJ in these Southern African states. The paper is based on a literature review and secondary sources on TJ in South Africa, Mozambique, and Angola. It shows written academic works of the transitional justice mechanisms in these Southern African states. Basically, the paper is descriptive in nature and historical method or Ex-post facto is employed. The paper shows that TJ processes do not necessarily have to be Western oriented or liberalist in approach. They can be locally driven or traditionally crafted depending on the context of the country. The article argues that in South Africa, Mozambique and Angola, different approaches were employed and all had some level of success. Therefore, Africa can always use African post-conflict mechanisms, not Western, to promote peace and reconciliation on the continent.

Key word: Transition justice, human rights, post-conflicts, Southern African States.

INTRODUCTION

For so many years, African countries have been faced with the challenge of how to address their ugly past. Since the 1990s, a good number of countries on the continent have made attempts to address past human rights abuses. In Africa, more than half of the 55 countries have established Truth Commissions in one form or another to help shape a better future. Arguably, the most significant of these commissions was the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (Fombad, 2022). But states such as Burundi, Central African Republic, Chad, Democratic Republic of Congo, The Gambia, Rwanda, Ethiopia and Ghana amongst others also had some form of transitional justice (especially truth commissions). These abuses emanated from conflicts or repressive regimes. The continent relies on a varied transitional justice mechanism: truth-seeking, prosecutions, institutional reforms, reparations, and reconciliation to deter further conflicts and recurrences of human rights abuse. However, Africa always lacks the political will and a weakness of state institutions to address a part of her regrettable past. Many Africans continue to yearn for accountability, reconciliation, and peace on the continent. To many commentators, transitional justice is the remedy to a peaceful, prosperous, and stable Africa.

However, some African nations always lack the political will and a weakness of state institutions to address a part of her regrettable past. To restore peace and enhance stability on the continent, the international community does promote power sharing arrangements in post conflict ridden states in Africa (International Center for Transitional Justice, 2009).

These solutions, however, frequently fail to address the core causes of conflicts and do not bring justice to victims of human rights violations. Truth commissions have been the characteristics of these TJ processes, despite the fact that other transitional justice programmes have been adopted in various African states. The mechanisms are made more complex due to the conflicts in states where negotiations and power-sharing are required for an effective transition to take place. Power-sharing employed as a conflict resolution tool does lead to impunity and undermines the delivery of justice in post-conflict countries on the continent (Koko, 2019). For example, The Gambia’s TJ process was mainly centered on the Truth Reconciliation and Reparations Commission (TRRC). The other mechanisms did not produce the desired results. The TJ mechanisms are not very holistic because most of the efforts are concentrated on Truth Commissions while other parts such as institutional reforms are neglected. As a result, the African Union Transitional Justice Policy (AUTJP) aspires to offer policy parameters for holistic and transformative TJ in Africa, based on, among other things, the AU Constitutive Act, Agenda 2063, the ACHPR, and the AU shared-values instruments (African Union, 2019).

If we believe that one of the main goals of Truth Commissions is to give a people or society the platform to learn from its past in order to prevent a repetition of violence in the future, it is quite clear that more needs to be done to make truth commissions in Africa effective and purposeful (Fombad, 2022). It appears that Africans do not fully learn past lessons from hearings conducted at truth commissions. Basically, transitional justice initiatives are not properly implemented in the countries cases and Africa as a whole. Despite the fact that African states coming out of conflict or authoritarian rule always use transitional justice, the mechanisms are either poorly implemented or not implemented at all (Dersso, 2017).

Otherwise, the cycle of repeated violence and gross human rights violations will not occur on the conflict. This article provides an overview of the TJ processes in South Africa, Mozambique and Angola. It examines their successes and failures and looks into the lessons learnt. It concludes by proffering some practical solutions for effective implementation of transitional justice in Africa.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

Transitional Justice (TJ) has now become a key mechanism used by post-conflict or countries emerging from gross human rights violations. This mechanism comes in diverse forms and is applied differently by different states depending on the magnitude of the crimes committed and the context (culture and religion) of a given country. Transitional justice is a response to systematic or significant violations of human rights that both compensates victims and improves prospects for the transformation of political systems, conflicts, and other situations that may have contributed to abuses (United Nations, 2008:1). It is critical to emphasis that the primary goal of transitional justice is to prevent the recurrence of human rights violations in a post-conflict society. In some circumstances, a conflict may not occur, but serious human rights violations can justify the adoption of transitional justice in a country. The term "transitional justice," sometimes known as "justice of transition" or "justice in transition," was coined in 1992 by New York judge Ruti Teitel (JUSTICEINFO.NET, 2016). The UN Human Rights Commission is also active in the implementation of transitional justice in a number of nations. As a result, transitional justice is multifaceted and varies among societies. The complete spectrum of processes and methods connected with a society's endeavor to come to terms with a legacy of large-scale past atrocities in order to ensure accountability, serve justice, and achieve reconciliation is referred to as transitional justice (UNITED NATIONS, 2014:10). Most of the world's TJ processes have occurred in Africa. This is due to the continents various conflicts and harsh regimes. As a result, the AU developed a transitional justice policy tailored to the continent in 2019. TJ is defined in that document as "the various (formal and traditional or non-formal) policy measures and institutional mechanisms that societies adopt through an inclusive consultative process to overcome past violations, divisions, and inequalities and to create conditions for both security and democratic and socioeconomic transformation" (African Union, 2019:4). Transitional justice is not a novel concept in today's world. It can be traced back to truth-seeking procedures established in Latin America or even the Nuremburg Trials held in Germany after WWII. According to Bosire (2006:4), writing for the International Centre for Transitional Justice:

Truth-seeking techniques can work alongside trials by allowing society to get a better understanding of past injustices. Truth commissions, which have a long history in Latin America and were popularized in Africa by the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), can allow victims to talk about their experiences and criminals to accept responsibility.

"Transitional justice refers to the ways countries emerging from periods of conflict and repression address large-scale or systematic human rights breaches so that numerous and serious conventional legal system will not be able to provide an acceptable response," according to the (ICTJ, nd). According to this reputable international organization, "in the 1990s, numerous American academics coined the term to characterize the many ways that countries tackled the problems of new regimes coming to power confronted with huge transgressions by their predecessors."

Many scholars have also linked the rise of transitional justice to the Tokyo and Nuremburg trials. They are regarded to be the first post-conflict procedures designed to avoid the repetition of atrocities and egregious human rights crimes.

According to (JUSTICEINFO.NET, 2016), "today's notion of transitional justice is linked to the evolution of war laws and international criminal justice, particularly the Tokyo and Nuremburg trials of crimes committed during the Second World War in 1945." Former Yugoslavia (1993, ICTY), Rwanda (1994, ICTR), South Africa (1994, TRC), Tunisia (2010, Ben Ali), The Gambia (2018), TRRC, and other jurisdictions afterwards implemented transitional justice structures. The fundamental goals of transitional justice are to remedy previous human rights violations and prevent them from happening again. However, transitional justice can also be used to prosecute perpetrators of horrible crimes and bring a divided state back together. This can only be accomplished via honesty and accountability. "Criminal prosecutions, truth commissions, reparations, institutional reforms, and memorialization are the key transitional justice instruments for dealing with past human rights violations" (2019, Political Youth Network).

Transitional justice has various advantages when it comes to reconstructing and reconciling a country. It also aids in the investigation of crimes and the shaping of a better future. According to Zyl (2005), transitional justice can provide the following benefits:

Examine the root causes of conflict and make recommendations to avoid recurrences; Prosecute and punish perpetrators of crimes, hence minimising victims' thirst for vengeance; By removing former abusers from government and enhancing institutional effectiveness and human rights standards, it can contribute to state development and institutional reforms; Truth commissions and reparations initiatives can raise awareness about the vulnerability of marginalized communities and help to address inequities; and By exposing wrongdoing and fostering accountability, it can advance the rule of law, restore trust in state institutions, and solidify democracy.

SOUTH AFRICAN TRANSITIONAL JUSTICE

When transitional justice in Africa, or even globally is discussed, South Africa always comes into mind. This is due to her supposedly successful and highly acclaimed transitional justice process. Historically, South Africa was a highly divided country-with an 80% Black population and the rest Brown and White of Indian and Dutch origin. This Black majority suffered a long and terrible White dominated rule-Apartheid. It was a discriminatory and oppressive regime which witnessed grotesque and heinous human rights violations. In 1992, when apartheid came to an end and democracy emerged, South Africa under Nelson Mandela, instituted a transitional justice system. Writing about transitional justice in South Africa, (Van der Merwe and Lamb, 2009:1) relates that:

South Africa's transition from apartheid to democracy involved a number of national procedures aimed to confront the country's violent and tragic past and transforming it into a stable and peaceful state. Among these projects was a process to disarm, demobilize, and reintegrate ex-combatants in order to form a new defense force by combining rival parties' armed forces into a unified military force. Figure 1 show the picture of Nelson Mandela being released from prison on February 11, 1990 | South African History Online.

South Africa's transitional justice comprises of the demobilisation and reintegration of ex-combatants into the South African National Defense Forces due to the country's history of militarised armed conflict between state forces and their opponents such as the African National Congress (ANC) (SANDF). Aside from this, the South African transitional justice system includes other processes like as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), prosecutions, reparations, institutional reforms (referred to locally as "transformation"), and other local transitional initiatives. Throughout South Africa, a diverse range of local justice and reconciliation projects have been formed independently. Restorative justice dialogues, local community healing meetings, victim counseling programmes, disappearance support and inquiry programmes, survivor advocacy initiatives, ex-combatant reintegration programmes, and memorialization projects are just a few examples. Van der Merwe and Lamb (2009:23) states local efforts aided in reaching out to and allowing many victims and perpetrators of crimes to reconcile. South Africa has made institutional transformation a core component of its transitional justice programme since the end of apartheid. It was intended to treat the underlying issues that had led to their heinous past. This was particularly noteworthy since apartheid was a legally, socially, economically, and culturally established system that discriminated and persecuted South Africa's majority blacks. Institutional reforms penetrated deeply into social, cultural, and land issues. Most of the measures described, such as land restitution, began before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was established in December 1995 and operated in tandem with it (United Nations, 2014:50). According to the UN, the TRC received 76,696 claims, the vast majority of which were settled. Nonetheless, it is somewhat ironic because the TRC employed accountability rhetoric while also granting multiple amnesties to perpetrators of human rights breaches (Emmanuel, 2007).

Though criminal prosecutions were part of the transitional justice processes in South Africa, they were not a foundational element of the system. Prosecutions were only used against perpetrators who fail to seek amnesty. “In South Africa, criminal prosecution was not the main mechanism of TJ. It was envisaged only as a conditional measure to be used for those who did not apply to receive amnesty or to whom the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) refused to grant amnesty (African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights, 2019:24). Essentially, prosecutions were few and far between since most offenders of human rights breaches were granted amnesty. Human rights abuses were prosecuted selectively and most offences went unpunished since they were legal under apartheid. As a result, "serious questions about the cost of impunity have also been raised." "Most human rights violators are perceived to have gotten a slap on the wrist, while most apartheid perpetrators, notably political leaders, are perceived to have escaped punishment and consequences for their past deeds." Van der Merwe and Lamb (2009:24) states that unless the offences committed were beyond the amnesty criteria, the country's TRC avoided prosecuting offenders or perpetrators of crimes (Emmanuel, 2007). In terms of disarmament, demobilisation, and reintegration of ex-combatants into the SANDF and civil life, (Van der Merwe and Lamb, 2009) demonstrated the following failures:

- Civil society and proponents of human rights did not play an effective part in the negotiations.

- TRC does not have an adequate policy in place to engage the new integrated military structure.

- The amnesty process of the TRC was hampered by a lack of clarity on the status of different applicants who claimed to be fighters.

- The TRC's amnesty procedure excluded civil society.

Other authors, on the other hand, lavish respect on South Africa's TJ process, particularly its TRC. Many believe that the TRC inspired people of all races to seek truth and reconciliation. Both the victims' and amnesty hearings received wide media attention, including live radio and television broadcasts, daily newspaper summaries, and the release of verbatim transcripts on the TRC website (Backer, 2005). The public hearings TRC resulted in national reconciliation and healing.

However, many victims were dissatisfied with the amnesty measures and contested them in court. Even though the TRC was faulty in various ways, it served as a model for subsequent truth and reconciliation commissions (Emmanuel, 2007). Most experts now think that the TJ processes in South Africa contributed to the country's unity and healing.

Nonetheless, there are mounting concerns that the TJ mechanisms did not go far enough in pursuing serious human rights violations. Some South Africans argue that the TRC was unbalanced and did not advance the country's much-needed reconciliation. The commission is frequently accused of not treating violations and crimes committed by liberation movements with the same seriousness as those committed by security forces (Emmanuel, 2007).

Furthermore, land reforms, a critical component of the TJ, failed to return lands to their rightful owners. As a result, South Africa remains a very unequal country with high levels of crime and unemployment. Unfortunately, the very blacks who bore the brunt of apartheid oppression are now bearing the unpleasant side of democracy.

TRANSITIONAL JUSTICE IN MOZAMBIQUE

Mozambique was another Southern African country with TJ. This country saw one of the bloodiest civil wars on the African continent." Between 1977 and 1992, the Mozambican government party FRELIMO (Front for Mozambican Liberation) was at odds with the rebel group RENAMO (Mozambican National Resistance) (Denecke, 2019). According to reports, approximately one million people were killed, thousands were injured, and thousands of children were enlisted as child soldiers. After years of conflict, a peace deal was established, and a transitional justice procedure was initiated (Thompson, 2016:2).

On October 4, 1992, the Mozambican government (Frelimo) and the former rebel group Renamo signed a General Peace Agreement. The peace treaty resulted in massive sociopolitical changes. However, in terms of transitional justice, the Mozambican government never devised any policy or programme aimed to compensate victims while prosecuting perpetrators of war crimes.

Mozambican society was highly split as a result of a long civil conflict, and trust between communities was damaged and needed to be rebuilt. People were skeptical of one another, necessitating discussion and reconciliation.

Disarmament of the RENAMO rebels was part of the amnesty deal but they did not disarm completely. This led to heightened tension and continued mistrust in the country. Some victims were not pleased with the general amnesty accorded to perpetrators by the government. They saw the blanket amnesty as a miscarriage of justice. Again, (Denecke, 2019) argues that:

In general, the government's declaration of national amnesty made formal proceedings impracticable, and, unlike in many other cases, the amnesty laws in Mozambique were not accompanied by a truth commission. As a result, the government decided to focus solely on reconciliation, dismissing all requests for justice. The decision suited both FRELIMO and RENAMO and was based on practical concerns for sustaining peace in a highly divided country.

Mozambique, unlike other post-conflict countries, did not adopt a policy for victim restitution. The victims were merely told to forgive and forget in order to foster healing and peace. The Mozambican General Assembly passed Law 15/95 two weeks after the peace deal was signed. All persons who committed crimes during the civil war were granted amnesty under this law (Thompson, 2016:2). As a result, victims and perpetrators had to coexist in the same communities, which bred a sense of vengeance in the victims.Furthermore, Mozambicans have strong superstitious beliefs and socio-cultural traditions that aid in their healing. Despite the absence of a legal transitional justice structure, traditional beliefs facilitated the reconciliation process. "They used socio-cultural methods (magamba spirits by magamba healers) to resolve these abuses and injustices without instilling feelings of vengeance and physical violence" (Thompson 2016). The spirits, according to them, are those of fallen troops. Their non-judicial TJ method prevented further hatred and divisiveness in the country. They made sure that war-related wounds were healed and restorative justice was attained.

The TJ in Mozambique was anchored on the principles of silent and denial. The case of Mozambique has clearly shown African traditional non-judicial transitional justice mechanisms can be sometimes more effective in reconciling a divided post-conflict nations than the judicial and institutionalized ones. Thus, indigenous mechanisms might be the viable alternatives for reparation, reconciliation restorative justice and peace building in post-conflict states (Thompson, 2016:3). Indigenous TJ processes could help in re-activating the spirit of truth-telling and reconciliation amongst citizens in a nation-state. It could also reintegrate perpetrators of crimes into the society.

Transitional justice mechanisms are also expensive to implement, especially truth commissions. Contrarily, the Mozambican indigenous model was more affordable, accessible, and responsive to the needs of the ordinary people.

This is because it was built on informality and proximity in contrast to conventional justice mechanisms. The rural communities of Mozambique were able to deal with the abuses while without interfering with the nationwide amnesty by using customary processes. Rituals were used to reintegrate victims and perpetrators into the community, as well as to renew cordial relationships between the living and the spirits (Denecke, 2019). Specifically, the criminals admitted their misdeeds and begged forgiveness from their victims, even if they were deceased. Offenders also take an oath never to commit a crime again and, in some situations, pay minor fines to the victims. Authors, on the other hand, have argued against indigenous TJ mechanisms. Some argue that they downplay past human rights breaches by failing to prosecute criminal perpetrators. Others claim that elite groups, politicians, and the government frequently exploit them. There are also claims that they are patriarchal in character, so excluding women from decision-making. Mozambique's case highlights the significance of grassroots participation in the transitional justice process. The top officials of FRELIMO and RENAMO advocated amnesty, but the public chose traditional processes based on their culture (Denecke, 2019).

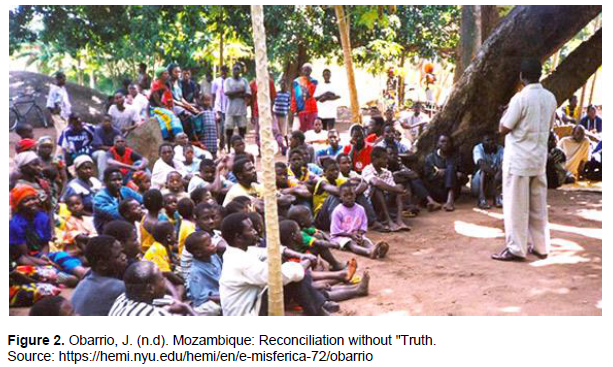

However, the peace agreement in the country failed to cater for transitional justice mechanism. It gave the government of Mozambique sole authority to give amnesty to all combatants prior the peace talks (Koko, 2019). The country basically ignored all forms of retributive and restorative justice. Figure 2 show the picture of juan Obarrio.

TRANSITIONAL JUSTICE IN ANGOLA

Just like South Africa and Mozambique, Angola is another Southern African country which had a transitional justice process. Like Mozambique, Angola is a former Portuguese colony and it gains her independence in 1975. This country suffered a brutal civil war (1975-2002). "Immediately following its fight of independence against the Portuguese colonizers, Angola experienced a brutal civil war between 1975 and 2002." In the 1970s and 1980s, there was a "proxy Cold Struggle," which evolved into a "greed-based war over natural resource domination" in the 1990s. ANGOLA: THE PANDORA BOX OF "EMBRACING AND FORGIVING," van Munster and van Wijk, 2020. Many legal academics believe that war crimes and crimes against humanity occurred throughout this protracted struggle, which resulted in the deaths of an estimated one million people. van Munster and van Wijk proposed (Angola: THE PANDORA BOX OF "EMBRACING AND FORGIVING," 2020):

Since the end of the civil war, the government's approach to the past has been to "forgive and forget" and to look forward. This strategy was already established in the 2002 general blanket amnesty, which was agreed upon by the warring groups shortly after the assassination of the primary opposition faction leader, Jonas Savimbi, which marked the end of the civil war.

The civil war began on May 27, 1977, when the MPLA government violently suppressed an alleged coup attempt. Thousands of people were massacred or mistreated during this incident, known as a limpeza (clean-up) (van Munster and van Wijk, ANGOLA: THE PANDORA BOX OF "EMBRACING AND FORGIVING," 2020). It is largely believed that every family in the country was affected by the conflict. These crimes committed during the war were neither investigated nor prosecuted while president Dos Santos of the MPLA was in power (1979-2017). Angola was embroiled in one of the world's worst wars from 1975 and 2002. Around 500,000 people were killed in the battle, which pitted two erstwhile liberation forces against one other with Cold War superpower support. Faced with a battle that appeared to have no end in sight, the United Nations labeled it the world's worst war in 1993 (Taylor, 2015).

Meanwhile, ethnicity and tribalism were among the core reasons of Angola's strife. The liberation movements were associated with the country's major ethnic groupings. Each ethnic group was vying for control of state resources and the formation of a government.

Unfortunately, other external forces fuelled the conflict by supporting various movements. They provided arms and funding to different factions during the civil war. The struggle was prolonged by external influence, training, backing, and finance from many sources. For Kasrils (2015) noted:

The Ambundu people, other African countries, Cuba, and the Soviet Union all supported the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), which was founded in December 1956. The National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA), created in 1962, was rooted among the Bakongo people and passionately supported the restoration and defense of the Kongo kingdom, which was supported by the governments of Zaire and (at first) China. The Ovimbundu people served as the foundation for the National Union for Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), which was founded in 1996 by a notable former FNLA commander, Jonas Savimbi.

The civil war erupted primarily as a result of rivalry between two groups: the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) and the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (NUTA) (UNITA). UNITA revolted against the MPLA after it created a government in 1975. The unwillingness of the prominent liberation movements to share power within a multi-ethnic country was a major reason for the prolongation of civil conflict after independence (Kasrils, 2015). Figure 3 show the picture of Jonas Malheiro Savimbi, the UNITA leader and Angolan despoiler, who died on February 22nd, at the age of 67.

However, when Joao Lourenco succeeded Dos Santos in 2017, the situation was altered. By presidential decree, he formed a panel to address the complaints of all victims of political disputes that happened between 1975 and 2002. The panel is made up of representatives from many ministries, including the Defense and Internal Affairs Ministries, Former Combatants and Veterans of the Homeland, Mass Media, and Security Services (Angola: THE PANDORA BOX OF EMBRACING AND FORGIVING, van Munster and van Wijk, 2020). No one who committed crimes or violated the law was prosecuted or held accountable. Only those who were not eligible for refugee protection faced prosecution (van Wijk, 2019).

The panel was given two years to address all victims' issues — to heal the psychological scars of families and to rebuild the spirit of brotherhood among Angolans via forgiveness and reconciliation (van Munster and van Wijk, PUBLIC APOLOGIES IN ANGOLA, BUT FOR WHOM?, 2021). The commission's makeup of only MPLA ministers prompted concerns about its ability to reconcile the country. Some pundits chastised the panel for failing to include a huge number of victims who the government did not identify as victims of political strife. As a result, thousands of victims of wartime rape, looting, and child military recruiting were not covered by the commission's mandate. As the commission's work continues, it remains to be seen as what the ramifications of its final deliverables will be. Both the Angolan people and the international world backed the amnesty granted to offenders of human rights atrocities. The Angolan administration stated that amnesty is a step toward reconciliation in and of itself (van Wijk, 2019).

CONCLUSION

Transitional justice is an approach to systematic or massive violations of human rights that provides solace to victims and creates opportunities for the transformation of the political systems, conflicts, and other conditions that may have been at the root of the abuses. Transitional Justice is a multi-dimensional approach which entails various forms such as: truth commissions, institutional reforms, reparations, memorialization, and criminal prosecutions. The application of any of these mechanisms depends on the context of the country undergoing transitional justice. Basically, transitional justice is aimed to address gross human rights abuses and avoiding their recurrences. South Africa, Angola, and Mozambique are countries in Southern Africa that underwent transitional justice or are undergoing it. All the three countries experienced civil wars and had to address their ugly past. Their transitional justice mechanisms were largely for reconciliation with little criminal prosecutions. Amnesties from prosecutions were mainly accorded to most of the perpetrators of human rights abuses. Consequently, these countries continue to face inequality, injustice, and human rights violations. Despite its hailed success, South Africa’s transitional justice process, especially its much celebrated TRC, has left many questions unanswered. There still exist accusations and continued denials of responsibility by perpetrators of heinous crimes. Furtherance to this, the country still finds it difficult to bury the legacy of apartheid and a good number of the structural inequalities are in existence. Though there are barely any open hostility and gross human rights violations, South Africa does not have social cohesion or even a shared form of national identity. The TRC also did not succeed in unearthing the evil nature of the apartheid system.

The Angolan transitional justice approach did not follow the liberal method. It used a traditional method which is peculiar to the country and put reconciliation, not criminal prosecution, at the center. It was all about forgive, forget, and healing. Fundamentally, the approach was able to bring some semblance of peace and stability in the country. Due to her abundant natural resources, the country was not dictated by international donors or NGOs as to which post-conflict approach to employ. Contrarily, it used reconciliation because it believed it was the best to avoid destabilizing the fragile state. Just like Angola, Mozambique utilized a similar TJ approach. Unlike other post-conflict countries, Mozambique did not implement any program for the reparation of victims. The victims were just told to forgive and forget as a way of enhancing reconciliation and promoting peace in the country. Therefore, the various horrific crimes committed in that country were not thoroughly investigated and perpetrators were not prosecuted. Unsurprisingly, real peace and stability did not happen in Mozambique because perpetrators were emboldened and people were made to believe that acts of criminality bear no consequences. Notwithstanding, there was some form of reconciliation of the people of the country.

In order to have better transitional justice mechanisms or processes in Africa, the following recommendations are proffered:

- Avoid blanket amnesty as it can lead to recurrence of crimes and can embolden perpetrators. The most heinous crimes must be prosecuted to serve as deterrence.

- Relevant violations of economic, social, religious, and cultural rights should always be considered.

- A comprehensive approach to transitional justice should be used all the time.

- Traditional justice mechanisms should be implemented to better conduct TJ in Africa.

- Reparations of victims should be a primary goal of every TJ process.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights. (2019). Study on Transitional Justice and Human and Peoples' Rights. Bijilo: ACHPR. |

|

|

African Union (2019). African Union Transitional Justice Policy. Policy. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: African Union. |

|

|

Backer D (2005). Evaluating Transitional Justice in South Africa From a Victim's Perspective. The Journal of the International Institute 12(2):3 |

|

|

Bosire LK (2006). Overpromised, Underdelivered: Transitional Justice in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sur. Revista Internacional de Direitos Humanos. 3:70-109. |

|

|

Denecke H (2019). Peace vs. Justice in Mozambique. UK: University of Kent. |

|

|

Dersso SA (2017). Lecture: The State of Transitional Justice in Africa - Between wide application and deep contestation. Lecture. Johannesburg, South Africa: Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation. |

|

|

Emmanuel K (2007). Between principle and pragmatism in transitional justice South Africa's TRC and peace building. Institute for Security Studies Papers (156):1. |

|

|

Fombad CM (2022). Transitional Justice in Africa: The Experience with Truth Commissions. Global Law and Justice. |

|

|

ICTJ (n.d.). What is Transitional Justice? Retrieved October 9, 2021, from International Centre for Transitional Justice: |

|

|

International Center for Transitional Justice. (2009). Conflict and Transitional Justice in Africa. International Center for Transitional Justice. |

|

|

JUSTICEINFO.NET (2016). Transitional Justice Explained (INFOGRAPHIC). |

|

|

Kasrils R (2015). The Angolan Civil War (1975-2002): A Brief History. SAHO. |

|

|

Koko S (2019). The challenges of power-sharing and transitional justice in post-civil war African countries. African Journal on Conflict 19(1):81-108. |

|

|

Kristin, R. (2009). Crude Existence: Environment and the Politics of Oil in Northern Angola. University of California Press, Berkeley Los Angeles London. |

|

|

Thompson KG (2016). Indigenous Transitional Justice in Perspective: The case of Mozambique. Small Wars Foundation 4(11):41. |

|

|

Van der Merwe H, Lamb G (2009). Transitional Justice and DDR: The Case of South Africa. Research Unit International Center for Transitional Justice. |

|

|

van Munster M, van Wijk J (2021). Public apologies in Angola, but for whom?. |

|

|

van Munster M, van Wijk J (2020). Angola: the pandora box of" Embracing and Forgiving". 2020(January 14). |

|

|

Political Youth Network (2019). Why is transitional justice important? |

|

|

Taylor A (2015). A 27-Year Civil War, For No Reason at All. Retrieved September 11:2020 |

|

|

United Nations (2008). What Is Transitional Justice? A Backgrounder. UN 1-4. |

|

|

United Nations (2014). Transitional justice and economic, social and cultural rights. United nations human rights 1-66. |

|

|

van Wijk J (2019). Angola, war crimes and transitional justice. In: B. Hola, H. N. Brehm, & M. Weedesteijn, Oxford Handbook of Atrocity Crimes (pp. 1-23). Amsterdam: Oxford University Press. |

|

|

Zyl PV (2005). Promoting Transitional Justice in Post-Conflict Societies. Institute of Development Studies. |

|

Copyright © 2024 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article.

This article is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0