ABSTRACT

Shared governance is an ideal form of Institutional governance providing all stakeholders with opportunity to participate, fostering acceptance of decisions and effectiveness of organization. This paper evaluates the current state of shared governance as the ideal form of Institutional Governance in public Universities, in line with the provisions of the individual University Statutes drawn from the University Act 2012. There have been continued complaints, claims of un-involvement and dissatisfaction evident in many riots and demonstrations that have characterized higher educational institutions, despite the Kenyan Government’s concerted efforts to increase and ensure student participation in the Public Universities Governance. The purpose of the study therefore was to evaluate the state of university governance in public universities in Kenya. The study employed descriptive research design. The study was carried out in seven public universities in Kenya that had university charter by the year 2012. Stratified random sampling technique was used to sample 194 student leaders from 362 based on the offices within the student council. Quantitative data was collected using a survey research tool: questionnaire. The findings of the study on students’ involvement in share governance revealed that universities exercise shared governance within the organizational structure with a mean rating of 2.85, access to information (3.18) and conflict resolution (3.48). However, traditional governance was practiced in influence on resources (2.30) being a subscale of shared governance. I make a case therefore for student involvement in shared governance as envisaged by the legislation. The paper concludes that structures of shared governance provides overall, opportunities for students participation and these exists in the organization to increase shared decision-making across all four subscales of shared governance. However, the University Management need to improve on the students official authority to influence resources specifically in order to realize shared governance as envisaged in The University Act 2012 and their individual University Statutes in order to full promote the benefits of shared governance.

Key words: Student participation, student involvement, institutional governance, shared governance.

The term “shared governance” began to emerge in the literature following the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) pivotal “Statement on Government of Colleges and Universities” adopted in 1966 (AAUP,

1966). The statement rallies internal stakeholders governing boards, administrators, faculty, and students “in the belief that the colleges and universities of the United States have reached a stage calling for appropriately shared responsibility and cooperative action among the components of the academic institution” (AAUP, 1966). By the late 1960s, the stance of the AAUP for increasing consultation and communication between institutional constituencies “had the strength of general tradition” (Duryea, 1973 as cited in Boland 2005). The early 1970s signaled an early turning point in institutional decision making (Riley and Baldridge, 1977 as cited in Boland 2005). Ibijola (2010) noted that the history of students’ participation in management of institutions dated back to the 19th century when Bell introduced the method of drilling older children who later taught the young ones. By so doing, the teachers’ efforts became multiplied. The extent of student involvement in decision making is debatable with often conflicting viewpoints propagated by differing stakeholders depending on their background and world view. Basically, there are three viewpoints that guide the extent of student involvement in decision making.

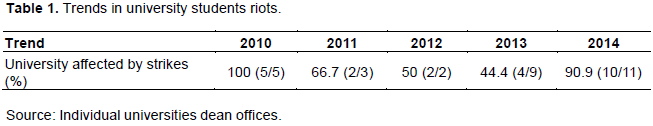

Shared governance means a shared responsibility and joint effort in decision making by all the major groups of stakeholders, including administrators, faculty, staff, and students, according to Cohen et al (1998). Shared governance is to formulate and implement meaningful ways to engage large numbers of people in the sharing process (Mortimer and Sathre, 2007). Other terms equivalent to shared governance seen in the literature include shared leadership, shared decision making, decentralization, decisional involvement, collaborative governance, and professional governance. Boland (2005) opined that, student representation in governance featured only marginally in heated debates in Ireland leading to the passing of the Universities Act (1997). More recently, although, recommending student participation in shared governance, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development report (OECD 2004) offers no rationale for their inclusion, while making a clear case for the inclusion of lay members. Despite being largely uncontested, student participation in shared governance of higher education institutions deserves greater critical attention, both in principle and in practice. While governance within higher education attracts increasing critical attention, participation of students has not featured prominently in these discussions (Salter 2002). In support of this the ministry of Education in Kenya under the leadership of Professor Kaimeyi (2015) recommended that student participation be put to practice as envisaged in the University Act 2012 that provides for student involvement in Institutional governance. These followed a wave of violent demonstrations and protests experienced in public universities as represented in Appendix Table A and Table 1; This table only represented the cases that were reported by the media and confirmed by the individual university dean offices not to mention the demonstrations and picketing witnessed within the schools/Faculty that went unreported. Of the 32 strike cases reported between 2010 to 2014 79.9% were directly involving student affairs as annexed in Appendix A. This then implied that the students were supposed to have participated in arresting these issues one way or the other, and suppose students did, it then implies that they re-engaged on their involvement, thus, the issues go beyond the actual involvement hence, the need to evaluate participation in shared governance. This therefore was the aim of the study, to evaluate institutional governance from student perspective both as stated and practiced. Based on the aforementioned therefore, student involvement cannot be over stated. Coupled with the continued complaints and unrests witnessed in the universities the study sought to evaluate the stated of the institutional governance shared governance being the ideal form of governance.

Purpose of the research

The purpose of the research is to evaluate the state of university governance.

Research objective

The research objective is to evaluate the state of shared governance in Public Universities in Kenya.

Research question

The research question is what is the state of shared governance in Public Universities in Kenya?

Significance of the study

The study is significant as it has shade light on the actual state of institutional governance with a view of providing insight on how institutions of higher education can fully benefit from the shared governance thus, making the Institutions meet their objectives through reduced students unrests and riots.

The concept of institutional governance

The literature describes several terms used interchangeably to describe shared governance such as shared leadership, shared decision making, and collaborative models (Hess, 1995). Tim Porter-O’Grady is well known for his extensive research and foundational groundwork on shared governance models. He describes shared governance as "a structural model through which nurses can express and manage their practice with a higher level of professional autonomy" (Porter-O'Grady, 2003). Porter-O’Grady describes his groundwork in his 1992 landmark book Implementing Shared Governance: Creating a Professional Practice. A review of the literature shows Dr. Tim Porter-O’Grady’s fundamental concepts of shared governance models are still relevant today and have not changed over the years. Many definitions are used to describe shared governance, but in summary, the literature defines it as a structure that promotes a culture of empowerment, autonomy, and decision making that occurs at the front line by the staff that performs the work (Doherty and Hope, 2000; George et al., 2002). Shared governance is the extension of power, control, and authority to the frontline staff and nurses over their clinical practice (Fray, 2011). Shared governance focuses on four main principles that serve as the foundation and the cornerstones of the concept. Collectively, when one incorporates the four principles of shared governance (partnership, accountability, equity, and ownership) into a team’s behavior, one creates a professional work environment of empowerment (Bates, 2004; Porter-O’Grady, 1992; Swihart and Porter-O’Grady,

2006.

“Shared governance is both an ideal and an operational reality that pertains to ways in which policy decisions are made in colleges and universities” (Hines, 2000). Corson (1960) as cited in (Kater et al, 2003) is credited for applying the term “governance” to higher education when dividing decision making between faculty, who had authority over curricula, instruction, research and classroom issues, and administration, who had authority over other institutional operations such as finance, student affairs, physical plant, and public relations (Mortimer and McConnell, 1978; Hines, 2000). Despite differences in spheres of influence in the governance of academic institutions, the role of faculty is both steeped in tradition and assumed as significant by those within the higher education community (Lee, 1980, 1981; Benjamin and Carroll, 1998). However, contemporary conditions such as globalization, academic capitalism, increasing governmental interaction, and turbulence (Kaplin and Lee, 1995; Slaughter and Leslie, 1997; Morphew, 1999; Hines, 2000; Levin, 2001a) affect the balance of power and players in institutional decision-making. The rationale for student participation therefore, was critically examined by Boland (2005) who, argues that if students are to play an effective role in governance, then they need to be positioned, not merely as clients, but as partners in the academic community with a long-term commitment to democratic principles and practice. The responsibility which higher education shares for the democratic socialisation process is raised. Thus, making a case for democratic practice at all levels of decision making, from the boardroom to the classroom, higher education institutions are to effectively prepare students for democratic citizenship. She concludes that shared governance is a necessary but an insufficient condition for the realisation of the democratic ideal within tertiary education and that other strategies should be adopted in tandem with statutory measures if higher education to play a role in cherishing, nurturing and protecting democratic values. Academics have a critical role to play in this endeavour (Boland, 2005).

This was a descriptive study to evaluate the current state of shared governance in public universities in Kenya. Thus, descriptive survey design was used because it helped to gather data at a particular point in time for the purpose of describing the nature of existing conditions, it identifies standards against existing conditions can be compared, and determines the relations that exist between specific events (Cohen and Manion, 1994). The population for this study consisted of 369 students’ leaders and from seven public Universities that had attained university charter by 2013 in Kenya. From the targeted study population, a representative sample was determined using the guidelines by Israel (1992) which was used to calculate a sample size for a given finite population such that the sample will be within +/ -0.05 of the population proportion with a 95% level of confidence. According to Israel (1992), he provides published tables, which provide the sample size for a given set of criteria. Thus, sample for this study was made up of 194 student leaders, stratified random sampling technique was used to select the sample population. The population was divided into stratas based on the offices they hold within the university to enable a fair representation of all offices. The questionnaire titled Students’ leaders Questionnaire (SLQ) was used for data collection. The tool was adopted with modification from the Index of Professional Nursing Governance (IPNG) survey tool to obtain a measurement of shared governance. The face and content validity of the instrument was assessed by two experts in Test and Measurement in the Faculty of Education, Maseno University, in order to ensure that the instrument adequately measured the intended content areas of the study. Their observations were used as a guide in reviewing the instrument before administering it to the subjects. The reliability of the instrument was ascertained using the split-half method, that is, the study utilized the scores from a single test to estimate the consistency of the test items. The split-half method reliability coefficient was corrected to full-length coefficient using the Spearman Brown prophecy formular. The resulting co- efficient was 0.89. Data obtained from the instrument were analyzed using descriptive. SPSS version 20 was used to analyze the data. The return rate of questionnaire was 97% as 190 out of the 194 respondents filled in the questionnaire and returned. The demographic characteristics of the respondents are given as Appendix Table B.

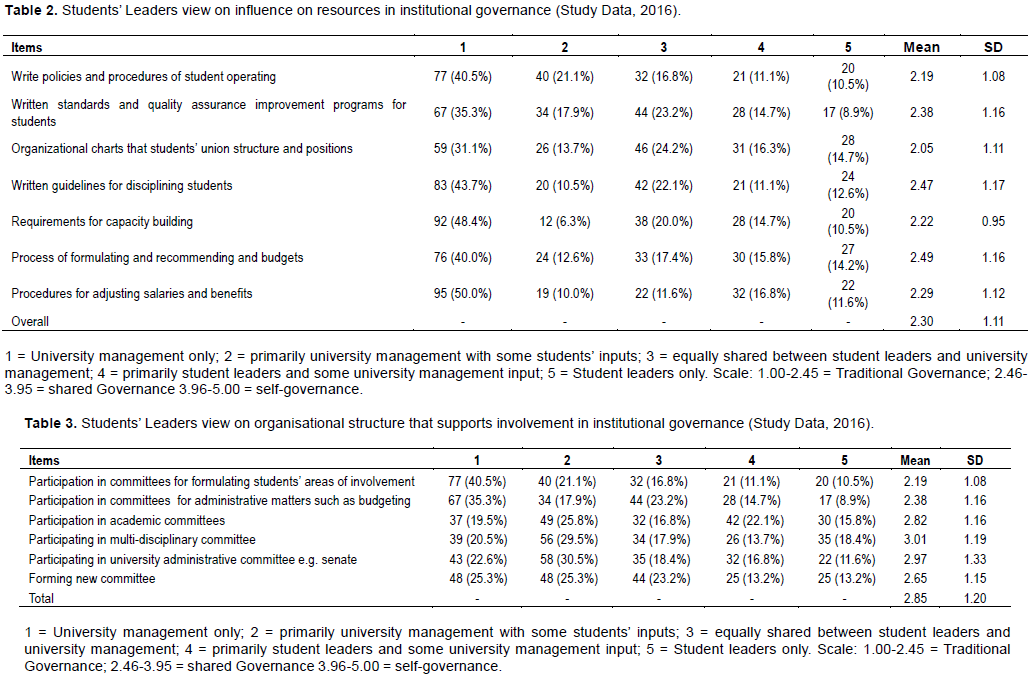

To answer the research question: what is the state of shared governance in public universities in Kenya? The institutional governance was investigated through the use of a questionnaire that measured institutional governance on a continuum ranging from traditional, to shared and to self-governance. Institutional governance is a multidimensional concept that encompasses the structure and process through which stakeholders control their governance practice and influence the organizational context in which it occurs. Higher mean scores indicate that the respondents, as a group, believe that they have more influence over governance practice and governance decisions in their organization. Student leaders’ opinions were sought on their universities state of governance. The respondents were presented with questionnaire whose items were related to areas of decision making linked to institutional governance as manifested by shared responsibilities and joint effort in decision making by major groups of stakeholders including administrators, staff and the students. The respondents were presented with items whose constructs sought which group in their institution had official authority to influence decisions and direct resources that influence decisions. The findings were presented separately in the four sub-scales and later jointly. The students’ leaders views were computed into percentage frequencies as tabulated in Table 2.

The findings of the study show that university management solely command most of the official authority to influence and direct resources that influence decisions in the university; students through their leaders have minimal authority granted and recognized by the institution to influence important issues in the university. This minimal influence by the student leaders was reflected by a low mean of 2.30 with standard deviation of 1.1.

Thus, the universities practiced traditional governance. It was established by the findings of the study that the university management alone preserves most of the authority to write policies and procedures of student operations in the university. This was revealed by many [7(40.5%)] of students leaders who took part in the study who held a general feeling that university management involvement in shared governance was overwhelming in terms of influencing and directing resources in writing policies and procedures of student operations, some 40 (21.1%) of the students also believed that although, students are involved in decision making as regards policies and procedures, university management primarily commands most of the authority in regards to policies and guidelines in the university. Only 32 (16.8%) of the student leaders held a perception that there is equal sharing of decision making between student leaders and university management in regards to policies formulation and general operations. On the contrary, some 21 (11.1%) of student leaders respondents alluded that although university management influence some decisions in the university, it is primarily dominated by student leaders and a further 20 (10.5%) of student leaders were of the general belief that student leaders have authority to significantly influence and direct resources towards policies and procedures in the university (Table 3).

The findings of the study show that more than half of the students who took part in the study generally held the perception that university management enjoy considerably more authority to influence and direct resources towards written standards and quality assurance improvement programs for students. This was revealed by 67 (35.3%) and 34 (17.9%) of students leaders who believed that university management only and primarily university management with some students’ input respectively, influence decisions regarding written standards and quality assurance improvement programs for students. On the flip flop, nearly one out of every four [44 (23.2%)] of the students leaders who took part in the study said their universities fully observe and practice shared governance in regards to standard and quality assurance improvement programs for students. However, 28 (14.7%) of them indicated that although, university management have some inputs on writing of standard and quality assurance programs, student leaders primarily has a bigger influence in this field, but a further 17 (8.9%) of the students leaders believed that the students solely have official authority to influence development of programs on the students standard and quality. It emerged from the findings of the study that many of the universities in Kenya involve student leaders in organizing structure of student unions only to some extent. For example, it was confirmed by 85 (44.8%) of the student leaders respondents that official authority to influence and direct resources on student union structure and positions majorly lies with university management. However, slightly less than a quarter [46 (24.2%)] of the students were satisfied with student involvement in shared governance; they alluded that decision on organizational charts that students’ union structure and positions were influenced by both the university management and student leaders in equal measure. On the other hand, some student leaders who took part in the study alluded that their influence on student leadership organization structure and position was overwhelming; some 59 (31.0%) of them observed that although, university management has influence but the major influence on student leadership is bestowed upon the student leaders themselves. On the contrary, it was established from the findings of the study that guidelines for disciplining students was largely [103 (54.2%)] a preserve for the university management, notwithstanding the fact that (42) 22.1% of the students leaders who were sampled for the study held a belief that there was shared governance in matters related to guidelines for disciplining students.

On matters related to capacity building for the students and staff, it came out from the findings of the study that majority [92 (48.4%)] of the student leaders respondents were in agreement that only university management alone have influence on requirements for capacity building. Only a fifth [38 (20.0%)] of student leaders were of the general feeling that students leaders were adequately involved in university governance in respect to capacity building matters, but some 20 (10.5%) of them alluded that only student leaders had influence on requirements for capacity building. The findings of the study show that although students’ leaders enjoy shared governance with the university management in some facets of decision making in the university, some decisions are left to a greater extent to the management only. For instance, it was established that university management enjoy full authority in influencing the process of formulating and recommending university budgets, as indicated by 100 (52.6%) of student leaders who took part in the study. Similarly, three out of every five [114 (60.0%)] student leaders who were sampled for the study were in agreement that procedures for adjusting salaries and benefits in the university were prerogative of the university management alone and the student leaders have no say over them and cannot influence anything at all. On the contrary, some respondents held a general feeling the student leaders, to some extent, have influence or involved in way or the other in almost all the activities in the university, including process of formulating and recommending budgets [22 (11.6%)] and procedures for adjusting salaries and benefits [33 (17.4%)].

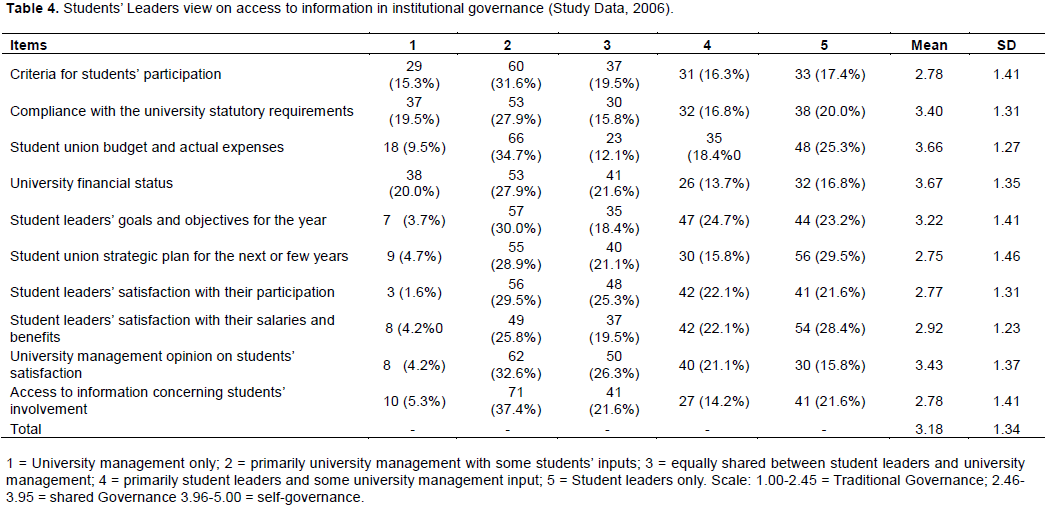

The findings of the study show that many universities have formulated ways of involving students in most of the decision making forums within the university, which have ultimately incorporated student voice into university governance forums. However, despite the formulation of these committees to create forum for students to participate in governance, students’ participation is still very low (mean =2.85 and Standard deviation =1.20). For instance, whereas only 44 (23.2%) of the student leaders accepted that they usually get involved to participate in committees for formulating students’ areas of involvement, more than a half [97 (51.1%)] of them insisted their involvement in such forums do not count much, given the fact that university management enjoy official authority to influence and direct resources where they are required. It emerged that only small proportion, 43 (22.6%), of the student leaders who took part in the study agreed that students leaders participate in committees for administrative matters such as budgeting, a bigger proportion [105 (55.3%)] of them alluded that although student leaders may have representation in committees for administrative matters such as budgeting, the university management have overwhelming influence on administrative matters. Similarly, although student leaders participate in university administrative committee such as senate meetings, their influence was established to be relatively low [35(18.4%)] with university management enjoying most of the official authority to influence both decisions and resources directed by this body. In addition, it emerged that a considerable majority of 101 (53.1%) of student leaders who took part in the study observed that university management alone has official authority to significantly influence decisions reached in committees for administrative matters. This finding implies that although students’ leaders participate in this committee, it is for no good since they cannot influence any decision, defeating the tenacity of shared governance.

It was also established that although students’ leaders are incorporated in academic and multi-disciplinary committees in the universities their influence was established to be non-significant. For example, 86 (45.3%) student leaders who participated in the study asserted that participation of the student leaders in academic committees was quite minimal compared to that of university management; the university management has the greatest influence in decisions made in academic committees. Similarly, 95 (50.0%) of the respondents observed that university management has the biggest influence in multi- disciplinary committee (mean=3.01 and Standard deviation =1.19). On the contrary, 32 (16.8%) and 34 (17.9%) of student leaders who participated in the study held the belief that there is sufficient involvement of student leaders in academic committees and multi-disciplinary committees, respectively. They alluded that the student leaders in these committees have equal opportunity of influencing decision reached in these committees. The study sought to investigate the level of access to information that the student leaders have as an aspect of shared governance. It emerged that the student leaders have fair information to enable them effectively participate and influence decisions in the university. This was revealed by slightly above average mean of 3.18, with a standard deviation of 1.18. For instance, whereas only 33 (17.4%) of student leaders respondents held the perception that student leaders have relevant information on criteria for students’ participation, 89 (46.9%) of the respondents said such knowledge is mainly held by the university management. However, nearly one out of every five [37 (19.5%)] of the student leaders who took part in the study were of the general feeling that information on criteria of student leaders participation in governance process was equally known by both student leaders and university management. On the same note, it was established that both the student leaders and university management have equal access to information on compliance with the university statutory requirements. This was reflected by nearly a fifth [37 (19.5%)] of the respondents who believed that university management have better information on compliance with the university statutory requirements and 38 (20.0%) others who were of the opinion that students leaders were equally informed.

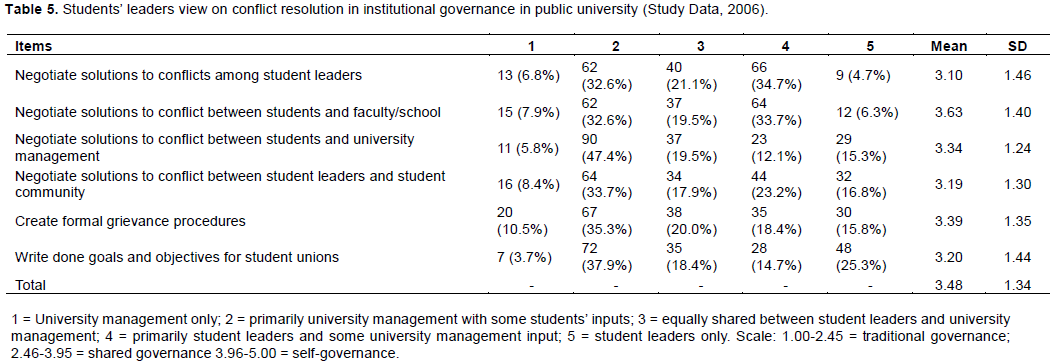

On the other hand, the findings of the study show that student leaders have better access to student union budget and actual expenditure compared to the university management. This was reflected by 48 (25.3%) of the student leaders who were in agreement that student leaders were more accessible to student union budget and actual expenditure compared to only 18 (9.5%), others who claimed that university management were more informed on student union income and expenditure than the student leaders. Similarly, the findings of the study show that the university management has the unequivocal access to information about the university financial status, as was held by a majority of 91 (57.9%) of student leaders. However, slightly more than a fifth [41(21.6%)] of the respondent held a contrary opinion, arguing that access on information on university financial status was equally shared between student leaders and university management. On the flip flop, the findings of the study indicate that although a sizable proportion [57 (30.0%)] of student leaders’ were of the belief that both student leaders and university management have equal access to information on goals and objectives of student leadership for the year, many student leaders have access to this information than the university management as confirmed by 70 (36.8%) of the student leaders who took part in the study. For instance, it was established that whereas nearly one out of every four, 44 (23.2%), of the student leaders who took part in the study observed that student leaders were more privy to information on student leadership goals and objectives, only 7 (3.7%) others who of the belief that university management have more access to this information than the student leaders. In addition, it emerged from the results of the study that a majority of 86 (45.3%) of the student leaders’ respondents held a perception that access to student union strategic plan for the next or few years was either fully or primarily held by student leaders in the universities. However, it was also discovered that some 40 (21.1%) others held a feeling that such information are equally shared between student leaders and university management, but another 55 (28.9%) were of the feelings that although the students have access to this information, university management primarily have the official authority over this information. Similarly, the findings of the study revealed that although more than a fifth, 41 (21.6%), of the students leaders who participated in the study generally believed that there is equal share between student leaders and university management on access to information concerning students’ involvement in university governance, 71 (37.4%) of them insisted that university management enjoy major influence in this field. When the study sought to find out whether student leaders’ were satisfied with their participation in university governance, it emerged that whereas about a quarter [48 (25.3%)] of student leaders indicated that they were happy, alluding that there was equal share in governance between student leaders and university management, a majority of 59 (31.1%) of them revealed that they were not satisfied with their participation in governance. They argued that the official authority to influence or redirect any action within the university is primarily owned by the university management and that student leaders are not given adequate authority to influence anything. On the other hand, it emerged that student leaders are fairly satisfied with the remuneration they receive for being student leaders. While only 57 (30.0%) of the respondents held a contrary opinion, a majority of 96 (50.5%) of them indicated that they were satisfied with their salaries and benefits as student leaders. The findings of study has shown that although university management has greater influence in most of the areas that involve decision making, the student leaders too have ability to shape some decisions in the university, as was reflected by slightly above average mean of 3.48 at a standard deviation of 1.34. For example, the finding of the study reveal that at the level of dispute between the students and the university, students’ leaders are invited to help in resolving conflict, as reflected in Table 4 and 5. It has been shown by the findings of this study that although nearly half, 90 (47.4%), of the student leaders who took part in the study held the perception that university management has major role to negotiate resolutions to conflict between students and university management, a significant proportion [52 (27.4%)] of them held that student leaders have more authority to influence the outcome of the negotiation during conflict resolution between students and university management. On the same note, it was discovered from the results of the study that both student leaders and university management have complementing roles in resolving conflict between students and faculty/school.

This was revealed by sharply divided opinions of the respondents; whereas 77 (40.5%) of the sampled student leaders held that university management has major role in resolving conflict between students and faculty/school, almost a similar proportion [76 (40.0%)] of the student leaders who took part in the study were of the view that student leaders have major role to influence negotiation for resolutions to conflict between students and faculty/school.

On creation of formal grievance procedures, the findings of the study show that university management enjoy a bigger authority to influence it. This was revealed by a majority of 87 (45.8%) of the student leaders’ respondents who held that university management has official authority to make decisions on creation of formal procedures of handling grievances in the university. These findings resonates with generally held opinion that although shared governance is necessary, there are some areas where student leaders make lack relevant experience and knowledge to effectively contribute in decision making. This means that although the students’ leaders get involved in most areas of decision making, however due to their limited exposure, they are not given equal status with their university management members in decision making in areas such as creation of formal procedures of handling grievances in the university. On the contrary, the findings of the study show that the student voices are easily heard in some areas compared to other areas, they get fully involved in matters that directly affect them and the fellow students. The findings of the study show that student leaders have naturally held control over resolving some conflicts. For example, whereas only 16 (8.4%) of the respondents strongly believed that university management has greater influence in the negotiation of conflict between student leaders and student community, twice as much [32 (16.8%)] others held that student leaders have the major influence in the outcome during negotiation of conflict between student leaders and student community. Similarly, during conflict among student leaders almost equal proportions of the respondents were of the opinion both student leaders and university management enjoy authority to negotiate resolutions to conflicts among student leaders. This was reflected by 75 (39.4%) of the students leaders who took part in the study who held that university management primarily influence the nature of resolutions to conflicts among student leaders and another equal proportion [75 (39.4%)] of them who were of the opinion that student leaders primarily influence solutions to conflicts among student leaders. On the contrary, more than one out of every five [40 (21.1%)] of the student leaders who took part in the study insisted that power to influence solution of conflict resolution between the student leaders is equally shared between student leaders and university management. On goals and objectives for students unions, the findings of the study discovered that nearly a fifth [35 (18.4%)] of the student leaders who participated in the study were satisfied that they equally involved in their formulation and setting. Nonetheless, there was a sharp division on opinions on which group wield more influence in this area; whereas 79 (41.6%) of the student leaders held the opinion that university management has official authority to influence decision on goals and objectives for student unions, another 76 (40.0%) of them held a contrary opinion. They were of the view that student leaders held a bigger share of influence on matters of student unions.

The study established that Kenya public Universities practiced shared governance with a mean rating of 2.95. However, there was disparity in the four sub-scales of the shared governance that is, with regard to influence on resources, the institutions had very minimal involvement in mean rating of 2.30 and a standard deviation of 1.11, thus, indicating traditional governance. The other three subscales had adequate student participation that is; organisational structure that support involvement in institutional governance (2.85), with conflict resolution having the highest level of involvement that is, 3.48 and access to information having a mean ration of 3.18. These disparities then imply that shared governance was more practiced in some areas than others. It is worth noting that, students’ views on their participation as regards to influence on resources, received very low mean rating because student participation at this level is by representation and not direct. This subscale was concerned with policies, processes and procedures within the public universities and thus, recorded per low student participation. These findings were in agreement with OECD report (2004) that recommended student participation in shared governance, although, not offering justification for their inclusion, making an apparent case for the addition of lay members. The study also concurs with others who established benefits of student participation in institutional governance; Adesanoye (2000) who, while citing Douglas submitted that, the rationale for students’ participation include among others, the development of ideas of right conduct, self control, co-operative and fairness, provision of training in leadership and development of a sense and appreciation of individual responsibility for the welfare of all group interest. The study also established a significant relationship between organizational effectiveness and the rationale for students’ participation in university governance. These findings point to shared governance as they are associated with benefits of thereby upholding shared governance to an organization. Thus, the rationale for student participation is critically examined and the argument is, if students are to play an effective role in governance, then they need to be positioned, not merely as clients, but as integral part of the governance especially where student affairs are concerned in both principle and practice. Institutional governance- university governance should be shared that is, there should be processes and/or practices that maximize the opportunities for involvement/participation of stakeholders at all levels in discussions, idea sharing and input to the decision-making processes that reduce discontentment and serves to guide strategic decisions by the organization and institution. It should also promote collaboration, thereby achieving optimal outcomes for the university.

The study concludes that Institutional governance is shared in public universities in Kenya evidenced by a mean rating of four sub-scales of 2.95. There is however traditional governance being practised with regards to Official Authority to influence on Resources with a mean rating of 2.30 and standard Deviation of 1.11. Shared governance is indeed evident in the other three sub- categories that is, organisational structures that support participation through the various committees, Access to Information and Ability to influence conflict resolution with mean ratings of 3.01, 3.18, and 3.48, respectively.

In view of the results on Official Authority of influence on Resources, organisational structures that support participation through these various committees, Access to Information and Ability to influence Conflict Resolution that constitute shared governance. The students need to be given orientation in areas where they are supposed to be involved in Institutional Governance. The University Management needs to provide adequate involvement/ participation of students to improve on the students’ official authority to influence resources. This can be done by allowing students to participate directly as they do in other committees. Communication should reach all the students in instances where participation is by representation. University management needs to solicit student views on the process, policies and procedure within the universities in order to facilitate student ownership of decisions thereof. In order to realize shared governance as envisaged in The University Act 2012 and their individual University Statutes in order to promote the benefits of shared governance in full.

The author has not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

AAUP (1966). Collection owned by the University of Mississippi, Archives and Special Collections.

|

|

|

|

Bates V (2004). Association of Perioperative Registered Nurses Journal. Shared governance in an integrative health care network 80(3):494-514.

|

|

|

|

|

Benjamin R, Carroll S (1998). Implications of the changed environment for governance in higher education. In: W. Tierney (Ed.), The responsive university. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press.

|

|

|

|

|

Boland J (2005). Student Participation in Shared Governance: A Means of Advancing Democratic Values. Article in Tertiary Education and Management. January 2005.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Cohen L, Manion L (1994) Research Methods in Education (fourth edition). London: Routledge.

|

|

|

|

|

Cohen LH, Cimbolic K, Armeli SR, Hettler TR (1998). Quantitative Assessment of Thriving. Journal of Social Issues 54(2):323-335.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Corson J (1960). Governance of colleges and universities. New York: McGraw Hill.

|

|

|

|

|

Doherty C, Hope W (2000). Shared governance-nurses making a difference. Journal of Nursing Management 8:77-81.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Duryea E (1973). Evolution of university organization. In M. Peterson, (Ed.). Organization and governance in higher education. Needham Heights: Simon and Schuster pp. 3-16.

|

|

|

|

|

Fray B (2011). Evaluating shared governance: Measuring functionality of unit practice councils at the point of care. Creative Nursing, 17(2):87-95.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

George V, Burke LJ, Rodgers B, Duthie N, Hoffman D, Burke LJ, Gehring LL (2002). Developing staff nurse shared leadership behavior in professional nursing practice. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 26(3):44-59.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hess R (1995). Shared governance: Nursing's 20th century tower of Babel. Journal of Nursing Administration, 25(5):14-17.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hines E (2000). The governance of higher education. In J. C. Smart & G. Tierney (Eds.), Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research, XV, New York: Agathon Press. pp. 105-155.

|

|

|

|

|

Ibijola EY (2010). Students' Participation in University Governance and Organizational Effectiveness in Ekiti and Ondo States Nigeria. M.Ed. Thesis Submitted to the Department of Educational Foundations and Management, Ekiti State University, Ado-Ekiti.

|

|

|

|

|

Israel GD (1992). Determining Sample Size. Agricultural Education and Communication Department, University of Florida, IFAS Extension, PEOD6.

View

|

|

|

|

|

Kaplin W, Lee B (1995). The law of higher education: A comprehensive guide to legal implications of administrative decision-making. 3rd Ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

|

|

|

|

|

Kater S, Levin J, Roe C, Wagoner R (2003). Not professionals?: Community college faculty in the new economy. Symposium for the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Chicago, April.

|

|

|

|

|

Lee B (1980-1981). Faculty role in academic governance and the anagerial exclusion: impact of the Yeshiva University decision. Journal of College and University Law, 7(3-4):222-266.

|

|

|

|

|

Levin J (2001a). Globalizing the community college: Strategies for change in the twenty-first century. New York: PALGRAVE.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Morphew C (1999). Challenges facing shared governance within the college. New directions for higher education 105:71-79.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mortimer KP, McConnell TR (1978). Sharing authority effectively. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

|

|

|

|

|

Mortimer KP, Sathre CO (2007). The Art and Politics of Academic Governance: Relations Among Boards, Presidents, and Faculty 1 Jan 2007 – 143 p.

|

|

|

|

|

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (2004). Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development report. View

|

|

|

|

|

Porter-O'Grady T (1992). Implementing shared governance: Creating a professional organization. St. Louis, MO: Mosby-Yearbook, Inc.

|

|

|

|

|

Porter-O'Grady T (2003). Researching shared governance: A futility of focus. Journal of Nursing Administration 33(4):251-252.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Riley G, Baldridge V (1977). Governing academic organizations: New problems new.

|

|

|

|

|

Salter B (2002). The external Pressures in the Internal Governance of Universities. Higher Education Quarterly 56(3):245-256.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Slaughter S, Leslie L (1997). Academic capitalism: Politics, policies, and the entrepreneurial university. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

|

|

|

|

|

Swihart D, Porter-O'Grady T (2006). Shared governance a practical approach to reshaping professional nursing practice. Marblehead, MA: HCPro, Inc.

|

|