This study originates from ongoing action research that aims to develop institutional opportunities to reflect on and take decisions about inclusion in the School of Accounts and Administration of Rio de Janeiro’s State Accounts Office. The research was organized in three phases. The first phase was an in-service course to sensitize professionals about inclusion. The second stage comprised the reformulation of the curriculum of the courses delivered by those professionals to other public servants; the third phase involved the creation and supervision of a discussion group that sought to develop cultures, policies and practices of inclusion. This study presents and analyses the first phase of the research from an omnilectical perspective. The question that guided this first phase was: what meanings of inclusion can be collectively derived from a course that aimed to sensitize a group to inclusion? The data was organized using Bardin content analysis technique, and discussed on the basis of the omnilectical perspective, developed by Santos. The results show the ways in which the participants “built” the concept of inclusion and their need to set up institutional practices based on participative citizenship, and to implement continuous evaluation of the teaching-learning processes.

This study originates from the first phase of an ongoing action research study initiated in 2013, entitled Inclusion in the Public Administration, which aims at helping the School of Accounts and Administration of the State’s Accounts Office to revisit its cultures, policies, and practices (Booth and Ainscow, 2011) of inclusion in order to become more inclusion-oriented. The concept of inclusion here adopted is based upon the omnilectical perspective, developed by Santos (2013). In her conception of inclusion, the author embodies the three dimensions developed by Booth and Ainscow and other aspects of their work and the work of others, as presented later.

This first phase of the research was carried out during an in-service 16 h course offered by the researchers to the school’s staff/teachers about inclusion in public administration at the request of the school director. These teachers are experienced civil servants who belong to the school staff. The course focussed on creating opportunities to reflect on the role of the school of accounts and administration, and of its teachers as inclusionary agents with a view to broadening the understanding of the principles of inclusion and, in so doing, bring the citizen to the centre of the teachers’ concerns, so that they would see the citizens as the main target of all courses offered.

The main idea was to add inclusion principles to the existing values of the school, in an assumption that this would help them to review their educational practices on a continuous basis. The underlying intention was to influence the teachers so that they would influence the planning and practicing of more inclusive social policy at the several municipal public administration offices that the school assists all over the state of Rio de Janeiro.

We consider this research as a relevant initiative given that the main mission of the school is to educate (train) civil servants of the 92 municipalities to abide by the rules of the Accounts Office of the State of Rio de Janeiro, and to monitor their compliance. To do so, the school provides training courses to the civil servants of those municipalities to help the municipal public sectors to deal with public accounts. These courses are taught by the School’s staff, who have two main functions: teaching the civil servants of the municipalities and supervising their work when visiting such municipalities over the year. The school offers, on average, more than one hundred courses during a year on various subjects, ranging from internal and external budget control to retirement concessions for the elderly, environmental education, etc.

Thus, this study presents the course given by the researchers to two groups of professional teachers of the earlier mentioned school, focussing on how those who are responsible for teaching the municipalities’ civil servants about public accounts and governance can develop the concept of inclusion after the course is completed. The underlying assumption was that the course could, in a chain reaction, reach the educators of public servants and, indirectly, the municipal servants under their jurisdiction.

Cultures, policies, and practices in dialectical and complex relationships: The omnilectical perspective of inclusion-exclusion

Society’s interest in thinking about living conditions in the world – shared by billions of people living in diverse social conditions, most of all poverty – has given rise to studies on inclusion. Conceptually, inclusion tends to be a very polysemic term, sometimes associated with underprivileged groups or sometimes focussing only on disability groups. In this study, the concept of inclusion is understood in a broader way, within a perspective known as omnilectics (Santos, 2013). This perspective acknowledges individual, social, group, and institutional life manifestations as pertaining to the dimensions of cultures, policies, and practices (Booth and Ainscow, 2011), which are dialectically (Lukács, 2010) and complexly related (Morin, 2008).

Inspired by Booth and Ainscow (2002, 2011), we believe that the dimension of cultures represents the personal level in which discursive practices are built, as well as all aspects and beliefs that will serve as justifications for the formulation and implementation of policies. Cultures of inclusion presuppose the participation of the citizens (practices) in the definition of priorities (policies) and on the processes of decision-making (policies), such as referendums, ballots, participative budgeting, local councils, etc.

Based on the work of the same authors (Booth and Ainscow, 2002, 2011) we state that the dimension of policies are related to the norms, laws, rules and regulations such as conventions, deliberations, or any other official statement that reflects cultures and points to practices. Policies can be more or less open to participation, according to how strongly linked they are to cultures. Slightly different to Booth and Ainscow, we point out that policies reveal the intentional actions of the state regarding society, but also reveal personal decisions towards oneself. The closer policies are to the wishes and aspirations of the citizens, the better the chances of them being effective.

Booth and Ainscow (2002, 2011) affirm that the dimension of practices represents the concretization of cultures and policies. This is the arena where decisions are taken into effect. As an example, we can say that the demands pointed to by the technical staff of an institution or the people of a city are expressed in its master plan. It is worth mentioning that the role of schools of accountancy will be defined, in the context of the managerial reforms of the political sector, by their contribution to the education of new professionals who engage in the widening of the social participation processes in order to develop ever-growing inclusive policies.

This was not the case until the year 1936; then the Brazilian public administration had inherited a patrimonial system from the Empire era which was then substituted by public bureaucracy. Currently, the public administration is on the way to becoming a managerial system. In this perspective, public developmental policies based on active citizens and on socio-political and economic inclusion are important. While being a fundamental governmental instrument for exercising – and maintaining – political power, public policies exist in a tense and politically dense arena, with conflicting relationships between the state and society, between the state’s powers, and among administrators and politicians.

In the transition from a patrimonial to a managerial perspective of public administration, there seems to be a qualitative leap when it comes to understanding the roles of civil servants, as they feel compelled to understand the concepts of inclusion and their applicability in formative processes. Thus, it seems now imperative to view corporative education as a means of avoiding punishment; hence the slogan adopted by the School of Accounts and Administration which is object of this research: “To educate in order not to punish”. It is along these lines that the omnilectical perspective was chosen as the means through which to analyse the data.

The word omnilectic is a neologism created by Santos (2013) to conceive a kind of analysis that intends to understand multiple factors simultaneously. It assumes that every human and social phenomenon is pervaded by the dimensions of cultures, policies, and practices, which in turn, are intimately and constantly interrelated in dialectical and complex ways.

Dialectic is adopted here based on Konder (1981) and Lukács (2010). The first author sees it as “the way in which we think of reality as essentially contradictory and in permanent transformation”. In this sense, the dimensions of cultures, policies and practices are always interrelated in contradictory and/or tense ways, and determine a constant state of change and transformation. As Lukács (2010) puts it: The essence of the dialectical method, in fact, is that in it, the absolute and the relative compose an indestructible unity: the absolute truth has its own relative elements related to time, place and circumstances. And, on the other hand, the relative truth, as real truth, as an approximately loyal reflection of reality, is embodied by an absolute validity (p. 12).

In other words, reality is multiple and has many cultural, political, and practical ‘layers’, so to speak, that represent both the essence of the phenomena and the phenomena themselves.

Such dialectic pervades all the reality, so that, in a relation of this kind, appearance and essence are made relative: what used to be the essence that contradicted the phenomenon emerges when we take a thorough (analytical) standpoint and overcome the surface of the immediate experience (and see it) as a phenomenon related to another, diverse, essence, which in turn will only be reached by means of even more thorough investigations. And so it goes on, indefinitely (Lukács, 2010).As for the complexity, we understand it as Morin (1995) puts it: representative of the self-organizational abilities of systems, as something that recognizes the uncertainty principle, which in turn leads us to recognize how exponentially changeable and temporary each reality is culturally, politically, and practically speaking. (...) any complex knowledge bears a part of uncertainty that needs to be acknowledged and recognized. Complex thinking comprises becoming aware of the lack of knowledge completion and, fundamentally, of a limitation of the human spirit’s possibilities. To search for absolute and undoubted fundamentals will [always] be in vain.

The difference between the omnilectical perspective and the known categories it embodies is not that it proposes a new concept of dialectics or complexity, but that it brings them together in the same perspective, as well as taking into account the three dimensions.

The Brazilian scenery of schools of government

Political and economic decentralization has been one of the strategies adopted by the public administration after the military regime ended in Brazil (1964 to 1985), in an attempt to remediate the negative legacy left by the regime such as:

[...] the lack of economic control, accountability of governors and bureaucrats before society, the undue politicization of bureaucracy in the states and municipalities, besides the overwhelming fragmentation of public enterprises due to the loss of focus on the governmental performance (Abrucio, 2007).

Despite the recurring criticisms about the way in which such decentralization has occurred in Brazil, it seems to be generally agreed that this process has brought more autonomy to the local governments as well as a possible improvement in social participation opportunities.

This improvement raised the number of functions of Schools of Accounts and Administrations, which are institutions created by the Federal Constitution of 1988 (Brasil, 1988) with the duty to educate public servants in the context of the administrative and managerial reforms of the state. They needed to become more educational than being purely fiscal.

They realized that educational initiatives could be more efficient than remedial actions when it came to results in public administration. Such a perspective was corroborated by Chaise (2007), when she stated that:

Within a scenery of great changes we can identify that public administration is no longer an administrative practice solely circumscribed by bureaucracy, but by citizens or aims strategically determined by its institutions. Here we call attention to the importance of Schools of Accounts as a means of putting this new focus into practice.

We believe that the broadening of participation also implies a practical broadening of the idea of inclusion, and this idea gained relevance in public policy texts throughout the 1980s, and especially in the 1990s. According to Santos (2013):

Inclusion is a process that reiterates democratic principles of full social participation. In this sense, inclusion cannot be resumed to one or some areas of human life, such as health, leisure or education (...) Inclusion, thus, refers to all efforts in the sense of guaranteeing maximum participation of any citizen, in any social arena.

Schools of accounts have as a basis for their pedagogical actions the principles of public administration such as, among others: legality, transparency, efficiency, efficacy, and technical competence. Added to these, the principles of inclusion may bring benefits to the government–citizens relationship. On the basis of these principles, the role of schools of accounts becomes crucial to the development of cultures, policies, and practices of inclusion in the public administration.

In this respect, it is no coincidence that the Strategic Plan of the State Accounts Office 2012 to 2015 shows, among its guiding principles, several ones that are directly linked with inclusion as an ideal and a principle to be pursued, such as independence, professionalism, ethics, and transparency. One responsibility of these schools is to improve public servants’ education on the basis of the idea of continued education, of learning organizations, and of the democratization of knowledge.

All these principles are somewhat linked to inclusion in the way we conceive it. Continued education is linked to inclusion in the sense that it provides opportunities for further reflection upon the day-to-day life of the institution and its role. Learning organizations relates to inclusion in that it means keeping an open mind for change. And the democratization of knowledge links to inclusion in the sense that knowledge represents a powerful tool for social change, and the more it is shared, the greater the possibility an institution has to adopt educationally oriented (as opposed to punitive) and emancipatory practices.

Thus, one can see that Brazilian Schools of Accounts have tried to better correspond to society’s expectations by increasingly valuing structural, physical, and cultural adjustments to the principles of inclusion. The underlying hypothesis is that by improving itself and its services, the school is also improving the qualification of the public servants. This inclusive, educational, and social qualification favours the implementation of new public policies, as well as the enhancement of society’s participation, which brings about a stronger exercise of citizenship.

The School of Accounts and Administration of the State Accounts Office of Rio de Janeiro has been working in this direction since 2010, performing the first steps to create inclusive institutional practices, cultures, and policies and promoting initiatives that strive for the improvement of pedagogical practices. This is done by incorporating inclusive principles into the principles already present in the school culture: commitment, ecological awareness, effectiveness, ethics, quality, independence, and entrepreneurship.

This project was initiated after an investigation carried out by the earlier-mentioned school in 2010, which aimed to map out the number of public servants with disabilities working at the State Accounts Office, in order to comply with the constitutional law. This legislation gives people with disabilities the right to compete for vacancies in public contests and aims to ensure that a quota of 5 to 20% is filled by employees with disabilities, depending on the number of employees the work place has. If there are more than a hundred positions, for instance, they must offer between two to 5% of the vacancies to disabled people.

Employers with more than 500 employees must offer 20% of positions to people with disabilities. The mapping showed that out of the 1500 public servants in the Rio de Janeiro State Accounts Office in 2011, 19 were people with disabilities, out of which four were visually impaired, 13 physically impaired, and two were hearing impaired. According to the constitution, at this total number of employees, there should be around 300 workers with disabilities; not just 19. These results led the school to make an extra effort to compensate for this imbalance.

Thus, after this investigation, other initiatives occurred, such as architectural accessibility refurbishment and a change in the identification form of servers allowing the identification of current and potential students via the internet webpage by means of two questions:

1. Do you have any disability and of what type? and

2. Do you need any adapted materials in order to facilitate your learning in the in-service education programmes? What are these materials?

In 2012, the school began a process of consulting special educational institutions in order to learn how to be pedagogically competent to develop actions for all civil servants, with or without any special needs, as well as to offer in-service education for its teachers and technicians to, in turn, educate people in the municipalities.

In 2013, the Laboratory of Studies, Research and Support to Participation and Diversity in Education of the Faculty of Education of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro was invited by the school to contribute to this project, which was named Incluir (meaning “to include”). The proposal was formatted within a covenant between the University and the School. The project, named Inclusion in the public administration: a study on the role of a School os Accounts and Administration in the development of cultures, policies and practices of inclusion, coordinated by one of the authors, began in 2013.

It is worth mentioning that we used Booth and Ainscow (2011) Index for inclusion: developing learning and participation in schools as the source of inspiration to conceive the research and its action developments. The Index is a set of materials originally designed to be developed with basic education schools. However, we have expanded the use of the Index to other types of educational institutions on the basis of our long term experience with such material, such as the case of the School of Government mentioned in this study.

Also worthy of mention are Booth and Ainscow (2011) definitions of the three dimensions of the Index – cultures, policies, and practices – which are the bases of the omnilectical perspective, explained earlier. Cultures are defined as everything related to values that are built and learned throughout life: precepts, principles, standpoints, perspectives of life; values we take for granted and defend without even noticing. According to the authors, policies refer to the organizational support institutions provided for the development of inclusion. Practices are what one is, what one does, what one performs, and how one lives.

Another important point to make is that, within the Index, cultures are seen as the pillar on which policies and practices can be built and reviewed. The authors point out that any change towards inclusion can only be possible when cultures are revisited and changed in democratic and participative directions. However, from the omnilectical perspective – because it sees these three dimensions as equally weighed in importance and because they are intertwined dialectically and complexly (as will be seen later) – any of these can be a pillar at any time, and this will always be so on a temporary basis, such is the dynamical movement between them.

In order to develop the research, as discussed previously, a covenant was signed between the university and the school. Once that was completed, we introduced the project to the school staff in order to identify those who would want to participate in it.

The first step of the project was to attend to a sensitization course on inclusion and public administration, and so the staff was invited to participate. For ethical purposes, those who agreed to participate signed an agreement of participation in the research in which it was clear that their identities would not be revealed and that they could stop participating in the research at any time, without any condition or charge. They also signed an agreement to the use of their images, allowing us to film and audio-record the meetings. Those who decided not to participate did so on the basis of lack of time, as they were not full time staff.

The idea of making room for reflection on the principles of inclusion in (their) education, together with their in-service training activities, was well received by the participants because they saw it as an opportunity for their own development regarding inclusion, both personally and professionally. As discussed previously, the idea was to contribute in the sense of adding inclusion to the values the school already had so that they would, if they so wished, be able to review their culture, policies, and practices and the curricula of the courses they offer to citizens and civil servants of the municipalities.

The course was delivered by the coordinators of the research (the authors of this article) – all of them researchers within the Educational field – and based on the assumption that a practice that is distant from the students makes the appropriation of knowledge and development of reflective skills – both very important in developing critical thinking – unlikely. In order to follow this assumption, the principles of inclusion as proposed by Booth and Ainscow (2011), mentioned earlier, were dialogically and participatively worked on, in an attempt to broaden the understanding of the concept of inclusion which is usually associated with disability.

Participants

We offered the course Inclusion in the Public Administration to staff who acted as teachers and course coordinators. The course was offered to two groups of participants. The first was composed of 27 people, out of which 19 were part of the school’s administrative technical staff (who, as said, are also teachers) and eight were just teachers, hired for these courses. The other group comprised 16 hired teachers. In total numbers, there were some 150 staff and hired teachers altogether, out of which the 43 mentioned above chose to take part in the workshops. The average participation rate over the course was 90%. All participants work in the School of Accounts and Administration which is focus of the research, and as such, live in the city of Rio de Janeiro and are responsible for teaching public servants of other municipalities to deal with public accounts and for monitoring the municipalities’ accounts.

The implementation of the course

The course ran from September to December 2013. Its main objective was to sensitize the participants to the principles of inclusion, based on the supposition that such principles offer the fundamentals of a learning that can be transformative because it promotes knowledge that is pertinent to the students. According to Morin (2008):

One needs to be able to view things within a context. It is not the quantity of information, nor the sophistication in Maths that can bring, on their own, a pertinent knowledge, but the capacity to put knowledge in context.

Thus, the course curriculum approached the theme of disability, but went beyond that by bringing in the participative aspects of inclusion, which centred the citizen as the reason for public policies’ formulation, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation. We had a total of four meetings on alternate weeks, lasting around four months, with the following subjects:

1. First meeting: theoretical approach to inclusion; inclusion as a principle (Booth & Ainscow, 2002).

2. Second meeting: the omnilectical perspective of inclusion and how it helps to develop inclusive didactics (Santos, 2013).

3. Third meeting: the citizen at the centre of the debate.

4. Fourth meeting: to educate in order not to punish.

During the meetings, the researchers played the roles of lecturer, participant observers, and debate leaders (the same researchers always attended each meeting). Because this phase was the first part of the action research that would follow, over the course of the meetings it was possible – even desirable – to review and change, if necessary, the contents in order to facilitate a self-revision process regarding the institution’s culture, policies, and practices by means of the participation of the people attending the meetings.

Data collection instruments

The meetings were filmed and audio-recorded and both were transcribed. For the purposes of this study, we used parts of the transcriptions of the audio material to illustrate the meanings attributed to the categories that emerged.

Analysis procedures

The data analysis focussed on identifying and valuing inclusive meanings the participants would develop regarding the public administration. Based on the omnilectical perspective, we considered their words during the discussions as potential institutional elements of cultural, political, and practical order which, because interrelated dialectically and complexly, could initiate revision and redefinition (if found necessary by the participants) of the institution based on the staff and institutional contexts.

To analyse the data, we also used Bardin (2006) content analysis, as we adopted an interpretative approach to the data. According to the author, content analysis is a set of techniques used to analyse communications with the aim of getting an indicator (quantitative or otherwise) that allows one to infer the knowledge related to the conditions of production; it also involves reception of the communications, via systematic and objective ways of describing the message contents.

The type of content analysis adopted in this part of the research was the categorical one. According to Bardin (2006), this is the oldest technique, and the most used. It is done by means of division of the material into unities and categories in a process of grouping and regrouping the contents under analysis.

This organization allowed for the gathering of a large amount of information, and then the correlation and transformation of this information from raw data into finished data. The categories were classified by one of the researchers/authors of this paper and further reviewed and agreed upon by the others. We remained only with the categories agreed upon by the four of us. The ones that showed any degree of disagreement were not considered. In this way, it was possible to reorganize discourses into categories. After doing this, we analysed them omnilectically. In so doing, we attempted to build, together with the group, their pertinent knowledge about inclusion.

Building the concept of inclusion

Group 1

This first exercise brought the participants together in pairs in order to exchange experiences, information, and understandings with a view to having them introduce words that provide the basis of their understanding of inclusion in the public administration, in a free association exercise. The words evoked by this group were the following: Efficacy, master plan, effectiveness, power, infrastructure, communication, education, participative budget, republic, social control, social debate, agility, circularity, concretization, rhetoric, diversity, freedom of expression, proactivity, ethics, credibility, motivation, plurality, transparency, knowledge, justice, citizenship, equity, democracy, decision, intentionality, collaboration, participation, integration, simplicity, access, reflection, dialogue, solidarity, isonomy, exhibition, culture, transformation, opportunity, perspective, functionality, respect, consciousness, altruism, legislation, common good, overcoming, process, social responsibility, policies, municipal councils, public audiences, academic discussion, health, leisure (notes from the daily diary).

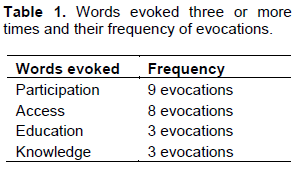

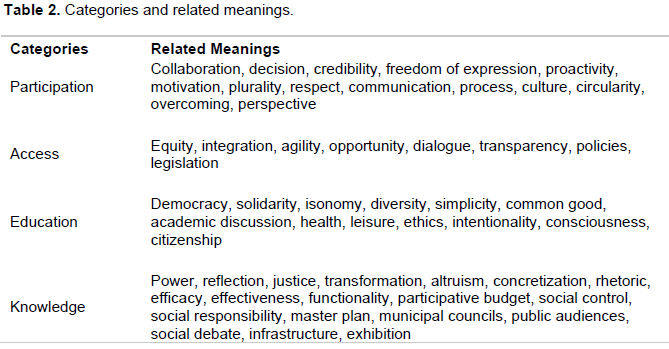

The words selected were annotated, and analysed on the basis of their frequency of evocation. After this, we chose to select for final analysis those that were evoked three times or more, and these were considered the main categories that gave meaning to inclusion. In this way, we were left with the following categories and respective number of evocations (Table 1). The group then was asked to reorganize the less evoked words within the four most evoked ones, used as main categories; the words within them composed their relative meanings (Table 2).

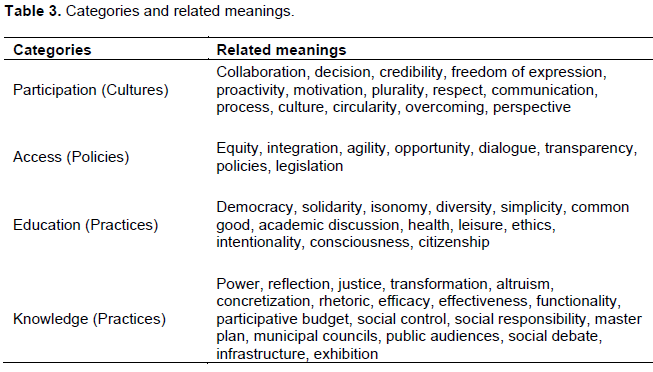

In this way, it became possible to see that for this group inclusion has to do with participation, access, education, and knowledge, and that each of these aspects are filled with several meanings. In the process of analysis, the participants should try to relate these categories to those of the Index and on which we based most of the course and its activities; that is, cultures, policies, and practices. In order to do so, another demonstrative board was organized by them, which attempted to guide their efforts as a team towards inclusive ideals (Table 3).

Thus, the category participation was understood to be inherent to the dimension of values (cultures) that need to be developed when searching for inclusive ideals. In this way, a great deal of the staff at the School of Accountability and Management understood the need to create cultures of inclusion via promoting collaboration among its technical staff, both in teaching and learning, by means of supporting and stimulating freedom of expression, proactivity, mutual respect, frank communication, and the circulation of information.

The category access was understood to be inherent to the dimension of policies which need to be produced in the search for inclusive ideals. According to the school staff, it will be vital to develop policies of access that ensure the equity and integration of all public servants and their jurisdictions; policies that provide dialogue and ensure transparency, both regarding information that circulates and decision-making processes; and policies that offer opportunities for public servants to professionally, cognitively, and personally develop themselves as well as favour speeding up internal bureaucracy.

The category education was understood to be inherent in the dimension of practices that need to be developed for inclusion to happen. In order to do so, education should mean transforming authoritative and hierarchical practices into ever-growing democratic and participative actions in order to ensure isonomy for people. Education should lead to the following: good citizenship, solidarity, diversity, common good, and awareness creation in public servants and their jurisdictions. It should broaden the academic discussions on the institutional role in promoting health, ethics, and leisure in a simple and intentional way.

The last main category, knowledge, was considered important to the dimension of practices and seen as in need to be developed in order to generate knowledge that empowers people and leads to autonomy, reflection, and transformation. It should be a knowledge that is guided by justice and that makes cultures and concrete policies that are functional, effective, and efficient for public administration and facilitates citizens’ exercise of social control, social responsibility, altruism, and public speaking. Knowledge should ensure adequate functioning of infrastructure and human life and it should favour the practice of social debate, represented in the actions of the municipal councils, participative budgeting, and public audiences.

Group 2

Slightly different from the previous group, this group listed the following words: Participation, transparency, knowledge, courage, responsibility, power, freedom, access, understanding, transformation, experience, exchange, will, democracy, rights, public sphere, consciousness, unveiling, referendum, reciprocity, attention, communication, evolution, interest, humility, tension, circularity (notes from the daily diary).

As shown below, there was some congruency between the two groups regarding the words and unit senses evoked by them. Again, we chose to select for final analysis those that were evoked three times or more (Table 4).

Of the evoked words, participation, transparency, knowledge, courage, responsibility, power, freedom, access, understanding, and transformation were considered to be categories of analysis, within which the remaining words should be organized. In the same way dine by the previous group, the participants of this group, all together and collaboratively reorganized the words, with the understanding that the less evoked words comprised the extensive meaning (sense units) of each category.

It is worth calling the reader’s attention to the word courage, which appears five times and is linked to the words attention, humility, and tension (Table 5). These words do not bear exactly the same semantic dimensions; on the contrary, they are quite different, semantically speaking, implying an underlying contradiction, as will be seen further on.

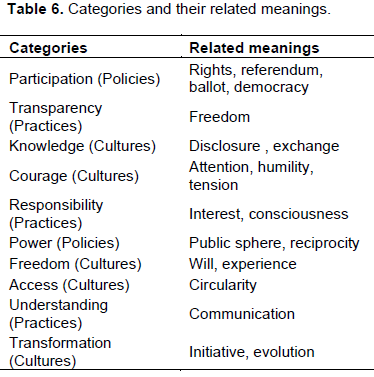

Thus, it is possible to observe that, for this group, inclusion seems to have to do with participation, transparency, knowledge, courage, responsibility, power, freedom, access, understanding and transformation, and each of these has a handful of meanings. In the analytical process carried out by the group, they related the categories to those predefined groups (cultures, policies and practices) and eventually built the board below, to demonstrate how they, as an institutional team, could guide their efforts towards inclusion (Table 6).

For this group, the categories participation and power were seen as inherent in the dimension of policies that need to be proposed so that the School of Governance and the Revenue Income Tax office can develop processes of inclusion. They were also seen as participation policies that guarantee the right to access the institutional level as well as broaden the access mechanisms to all persons, both civil servants and citizens. Finally, they were understood as social empowerment policies that reaffirm democratic processes, including referendums and consultations. The categories transparency, responsibility, and understanding were associated with practical dimensions that need be developed in order to accomplish inclusive ideals. In this way, making the inner and outer institutional communication processes more transparent and free, including the public sphere by means of civil participation, becomes a crucial means to promote inclusion. The ability to persuade each person to commit his/her individual and collective responsibilities to an interest in the institutional actions (School of Accounts Office) is also crucial in an attempt to continuously develop public awareness.

The categories of knowledge, courage, freedom, access, and transformation were understood to be inherent in the cultural dimension, showing the interest of the institution in developing inclusive values in their members so as to provide opportunities for the circulation of ideas, information, and people. For this group, it seems that the creation of a culture of knowledge implies bringing out what is unseen and to transform the public administration by means of bringing up new ideas and empowering participants.

Besides the development of a culture of knowledge, the development of values such as courage is related to the incentive of personal initiatives and the consideration of the wishes and motivations of each individual and the group. It seems that for this group, it is highly important to encourage an attentive, understanding, and humble spirit, especially when it comes to institutions of control, so that people can perform more inclusive public practices.

On the other hand, as mentioned earlier, courage can also contradictorily imply that behind the day-to-day life of the institution lies a strong hierarchical relationship in which, as the Brazilian idiom says: “Those who can, command. Those who are sensible, obey”. The comment below, made by Participant 4 while discussing how they, as teachers, could promote inclusion in that institution, is very representative of this point: “There is no ‘could’. Here we must follow what the House [referring to the school] thinks needs to be done.” Moreover, the list of words above shows an apparently broad understanding of the concept of inclusion by the public administration staff involved. These are words that, in a way, show the wish to change current practices and to improve autonomy and emancipation in the social actors involved. Although the words autonomy and emancipation were not explicitly mentioned by the groups, it is possible to infer that they are a desirable product of the process of inclusion, as reported by one of the participants: When we engage in a more participative lesson, we change our structures…. We destabilize certain practices (Participant 12).

Analysis: The coincident meanings of inclusion for both groups

In order to analyse the data presented in this study, we decided to use the categories that coincided in both groups: participation, knowledge, and access. These categories, in accordance with the participants, should be the basis of the development of processes of cultures, policies, and practices of inclusion in their professional context. These aspects are consistently discussed and proposed to be worked with because they are constitutive of the “movement” of inclusion in the Index.

Participation is, perhaps, the central concept. As Booth and Ainscow (2011) put it, it is by means of interactions, exchanges of experiences, and participation that people become able to share inclusive values, to review conceptions and postures, and to build other ways of being an educator.

The idea of participation is structured in a complex and dialectical way, as proposed by the omnilectical perspective as it relates to togetherness, to ethically challenging visions and beliefs (cultures), restructuring policies and practices, and collaborating with others. It also has to do with engaging in the institution’s activities and routines, and linking every act to ideas of democracy and freedom.

Moreover, as Booth and Ainscow (2011) point out, it has to do with the right to not participate. It involves dialogue with others on the basis of respect and equality and, as such, it demands that we consciously leave aside differences of status and power. Participation improves when the engagement reinforces one’s sense of identity; when one is accepted and valued for being what one is.

The meanings attributed to participation by the groups are all related to the above view, but they also bring out, for some, barriers in the school regarding participation. We say this because during some occasions we observed participants of the groups attributing words that they wished were implied in participation, rather than what they experienced on a daily basis. For example, one of the participants wrote, when asked about what a participative teaching methodology would be for her:

A participative methodology should take into account the 21st century student: a person connected to all forms of communication, always in a hurry to acquire knowledge, and who sees the teacher-student relationship in a very different way from my times and with very little respect for the teacher. The facilitating teacher is not yet well regarded by the students. In my opinion, in Brazil the students have a tendency to think that the teacher must teach everything that is necessary and needs to be taught, leaving very little room for the students to participate (Participant 23).

In this sense, in our interpretation, the meaning of participation is here linked to autonomous practices, power distribution and emancipation – or the lack of them. To whom the responsibility of considering the aspects pointed out by Participant 23 belong? Whose responsibility it is to change it? Kaczan et al. (2013), in a study investigating the formation of identity and social participation in schools of basic education, points that:

(…) school type seems to be a significant factor determining both the manner of defining life objectives by young people and the type of social participation, that is, commitment to roles and activities that help the fulfillment of the current and future tasks. If this is so, it is possible to infer that the School of Accounts has not yet become aware that the findings by Kaczan et al. (2013) could also apply to its context.

In an omnilectical analysis, both views of participation (what exists and what does not exists) are legitimate. They point to the dialectical (because somehow contradictory) and complex (because there is never a single factor to be considered) relationship among cultural (what the participants think, in the view of the cited teacher, for instance), political (when participants see the need for concrete engagement in activities and decision making of the institution), and practical (when they plan, when they relate to each other, etc.) dimensions, and the possibilities for coming to different (but complementary) conclusions whenever a new consideration of these relationships is taken.

With regard to access, on the basis of the analytical perspective adopted here – the omnilectics – we understood that the meanings highlighted by the groups go beyond those usually related to accessibility in Brazil. They go beyond the physical dimension and contemplate the cultural, political, and practical aspects which are dialectically and complexly related. Thus, access has to do with planning, group participation, maintenance of dignity of public servants and users of public services, identifying barriers that prevent people from accessing and sharing public spaces which, by their nature, should be available and accessible to all.

On the other hand, in order to provide this kind of access in their activities (including the courses they offer), time is a crucial element that is considered a barrier in many cases. In this regard, technical content is overvalued at the expense of content that could lead to a better understanding of the importance of the access in all the senses highlighted by the groups. As an example, one of the participants, when considering the importance of inserting content related to citizenship in the course he is responsible for (financial execution and budgeting), said that: I think that we can adopt more participative practices when it comes to relating the course contents with news of the media brought up by the students or the teacher. This is important to develop citizenship when it comes to participating in the control of public expenditures. However, in order not to compromise the relevant technical contents of the course, I suggest that another discipline be created just for that (Participant 15).

That is, this teacher seems to think of curriculum as needing to be separately organized into more typical educational contents and civic contents, as if their coexistence were not possible. In fact, according to Matos and Paiva (2009), the organization of the curriculum and of knowledge is pervaded by power relations which are different in the scientific, academic and school contexts.

To think of curriculum planning implies to think of the power relations that are constituted during the formative process in the educational institution and to consider the real possibilities for disciplines and integrated curriculum proposals to account for educational and wider social issues. In as much as we tend to agree with the author, it is wise not to forget that such consideration of possibilities does not need to mean that such aspects should be seen separately when conceiving the curriculum or an educational plan.

Omnilectically speaking, once more, the coexistence of different, even contradictory, and complex views on the matter of access is legitimate, as would be any other view depicted after another glance at the theme and the data. Their coexistence infers culture that values both the citizenship aspect of access and the technical aspect. It also infers policies that may contemplate such aspects together or separately (the curriculum of the course, for example, inserting citizenship contents in the same module or creating a separate module just for that). Moreover, it implies teaching styles (practices) that will range from more explanatory to more practical ones.

What we see in all these aspects, when looking at them from an omnilectical perspective, is that they are intertwined dialectically (because they do not always coexist without tensions) and complexly (because at any time we see them, we may perceive another form of understanding, neither better nor worse than the previous ones).

With regards to knowledge, its meaning goes beyond its polysemic aspects to be understood on the basis of the omnilectical perception of cultures, policies, and practices. In this sense, knowledge was implies acknowledging the institutional barriers that result in the possibility of assuming the limitations of cultures, policies, and practices at play. In so doing, one may embody new values that may transform the public administration, especially during the courses offered by the public servants. The main examples presented by the participants associate knowledge with participation, access, and emancipatory actions. When considering the objective of the course administered within an emancipatory perspective, one teacher says: The course aims to open up the possibility of making mistakes. When one makes a mistake, the inconsistency perceived in it generates elucidative critiques that make it possible for the student to identify his/her mistake, to consult the legislation, and to make it right; that is, it is self-educating (Participant 14).

The concept of knowledge for this teacher seems to be associated with overcoming mistakes and shortening the timeframe, and these, in turn, are related to the use of instruments and or applications that make it possible for students to simulate situations of fairer practices which ensure civil rights (as is the case in Brazil, with retirement). In this participant’s view, an emancipatory course seems to be one that can be translated into technical knowledge and be legally based.

This is consistent with the view of a critical evaluation in Nogaro and Granella (2012), for whom a critical model of evaluation is part of an integrated teaching, in which the teacher follows the learning process of the student being able to help him in his schooling process, on a dialogical basis, continuously reviewing and adjusting the teaching process, through which all students successfully reach the planned aims, revealing their potentials.

Omnilectically, we can question if it really is emancipatory to do ‘the right’ things and in a short time period. We see cultures (the need for speed, the perception of mistake as a means of making it right), policies (the curriculum organization of her course being planned in this way, trying to save time and yet opening room for simulations) and practices (the actual activities of the course, the use of simulation tools) that are both in accordance with each other and not, pointing to relationships that are complex and dialectical at the same time.

This study aims to present the first phase of a research study about inclusion within a School of Accounts of the Rio de Janeiro public administration. The phase consisted of the offering of a course, which held four meetings and attempted to promote knowledge about – and sensitize the participants to – the process of institutional inclusion and its formative practices.

In order to do so, we proposed activities that aimed to reflect and identify existing institutional and attitudinal barriers to try to minimize them (in the future, if theparticipants so wished). Our analysis pointed to a desire for change on the part of the participants: Group 1 listed the categories of participation, access, education, and knowledge as essential to build cultures, policies, and practices of inclusion; Group 2 identified 10 main categories: participation, transparency, knowledge, courage, responsibility, power, freedom, access, understanding, and transformation.

In both groups, we were able to point out both the consensual and contradictory aspects of the categories when interrelated with the subjects who elected them. Such coexistence of consensus and contradictions are typically found when we analyse data from an omnilectical perspective. This is so because such a perspective opens the possibility to see the immediately visible, but also the (so far, only) potentially imaginable; that is, what is said and what is silenced, or silent.

In addition, this perspective allows us to go further and observe that the same categories might have different meanings, depending on whether they are associated with the dimension of cultures (always harder – but not impossible – to change), policies, or practices, and that this should not be understood in a polarized, linear, causal view, because among the three dimensions, there is no higher importance for any of them, although one or another might appear as temporarily prevalent in a certain situation. But this is only temporary, because when the dialectical view is considered in the analysis of the dimensions, as well as the exponential possibility of rearrangements that the complexity allows, the omnilectical totality is perceived, and it is always changing, always moving, always varying and shifting directions.

Thus, we also observed coexisting contradictory and complex views in terms of what participants value and believe (cultures), in terms of how they plan and organize their routines (policies), and in terms of how they do whatever they do (practices). In this sense, while they express their wishes to be democratic, participative and inclusive, while at the same time they show an understanding of what such terms might mean in order to build a fairer society, they are also subjected to the inherent pitfalls of institutional life (with competitive cultures, for instance) and the structural contexts of exclusion in which the country, the city, their institution, and they themselves are immersed. A recurrent example in their discussions was to do with the openness of the School for people to express their impressions and feelings. Many would say the “openness” was not something instituted in their routine. The excerpt below is an example of these impressions:

I think this institution is still too tied to bureaucratic formalities, to accomplishing the daily tasks and to the lack of ability to hear and respect the individualities and the subjects. I must confess that it took me a while to feel that I could speak out what I feel and I imagine that this fear is also felt by my colleagues. (...) Definitely, inclusion is a complex action that goes well beyond disability issues. In many occasions we feel like a stranger.

Overall, we believe that the study presented contributes to research field by bringing about a discussion that is still seldom written about: Schools of Accounts and Administration as a potentially formative institution. For the same reason, we believe it is a relevant research. Moreover, it also presents some insight into the field of inclusion, given that it proposes a different way of looking at the inclusion/exclusion dialectic, that is, via the omnilectical perspective. In so doing, we were able to discuss how inclusion relates to broader phenomena than those linked only to disability issues.

Having said that, there were some limitations to the research as well. One is related to the little time allocated for the meetings, which sometimes made the data collection hard to be done, as most of the tasks through which we collected the data needed to be synthetized in a written form, and this would happen at the very end of the meeting, leaving the subjects somehow lacking in attention or wish to further do anything, so some would write too quickly or make a hurried comment, which might indicate answers little thought of.

On this basis, we recommend that more studies be carried out on settings like the one here described. Another recommendation is to do with the perspective here presented: the omnilectics. Such perspective could be further explored as a means of analysis and as a framework for understanding educational research data.

After all, the omnilectical view leads us to see that it is culturally, politically and practically possible for contrary perceptions and viewpoints to coexist, either pacifically or in tension. It also points that realities will keep endlessly changing and in this movement lies the possibility to enhance the potentials of social practices such as education. The direction of these changes remain to be seen (and always will).