Full Length Research Paper

ABSTRACT

The bounds testing (augmented autoregressive distributed lag, ARDL) technique to cointegration was used in this study to investigate the effect of household income and expenditure on tertiary school enrolment in Nigeria from 1970 to 2020. The model was employed to estimate the relationship between these three variables while also accounting for interactions with total education expenditure. When the dependent variable is tertiary school enrollment, the bounds tests show that the variables of interest are bound together in the long run. Tertiary education is widely regarded in Nigeria as a path to higher-paying jobs and a better quality of life, so some interesting observations were made. It was discovered that there is a significant negative relationship between GDP per capita, which is a proxy for household income. The findings also show that a household's consumption expenditure provides tertiary education enrollment power; an increase in a household's consumption expenditure increases the tertiary education enrollment ratio. When the variables deviate from their equilibrium values, the speed of adjustment to equilibrium is 128% within a year. The study suggests that the government establish more tertiary institutions and improve the reputation of existing ones by adequately funding them.

Key words: Household, income, expenditure, augmented autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL).

INTRODUCTION

Getting access to tertiary education is the most effective way for students from low-income or rural families to progress from the lower to upper class in society (Zhou, 2001; Xu and Yi, 2014). Tertiary education encompasses all post-secondary formal education, including public and private universities, colleges, technical training institutes, and vocational schools. Tertiary education is widely regarded as a path to higher-paying jobs and a better quality of life. Indeed, there is a direct relationship between higher education and development (Luhanga et al., 2003). The rate of development, on the other hand, varies from country to country. Universities, according to Altbach and Knight (2007), are the engines of the postindustrial age and the knowledge economy. The primary role of the university is multifaceted. While the ultimate goal is to develop a skilled workforce, the end result is economic growth. Alternatively, higher education and economic development are inextricably linked (Makulilo, 2012). Even when students attend public tertiary institutions where tuition is waived, tertiary education is not a free activity for families. Aside from the opportunity cost of tertiary education, households supplement government efforts in funding and preparing students for tertiary education. The cost of tertiary schooling to households includes monetary costs associated with schooling, non-monetary contributions such as time spent in tertiary school and travel to and from tertiary school, time and labor contributed by other household members in support of tertiary schooling (Yu, 2017). These monetary and non-monetary costs of tertiary education may be difficult for some households to bear and, in some cases, may be so burdensome that members do not attend tertiary school or leave tertiary education. Only 26% of the 10 million applicants who sought admission into Nigerian tertiary institutions between 2010 and 2015 were admitted, according to data from Nigeria's National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) and the Joint Admissions and Matriculation Board (JAMB) (Kazeem, 2017).

For the 1.9 million students who registered for the JAMB exam in 2019, there were only 1.1 million slots available across the country's tertiary institutions. In other words, 40.4% of students enrolled that year are automatically expelled. Some courses, such as medicine and law, are extremely popular. This is one of the reasons students were denied admission, according to JAMB. Individual tertiary education options are now limited not only by personal abilities, but also by the ability of families to finance education. As a result, families' financial ability to pay for tertiary education weakens the minimum ability requirements. For both state-subsidized and full-tuition students, the educational process and final certificates of degrees obtained are the same. As a result, under the current educational system, Nigerian youth have two options: they can be smart enough to enter universities, or their parents can "buy" them admission. A country's consumption expenditure patterns reveal the level of welfare and poverty that it is experiencing. An analysis of household consumption expenditure over time is very important in every country because it provides a clear picture of the various components of household consumption expenditure and consumption trends. It provides information about people's living standards and the degree of inequality. As a result, assessing the effects of household spending on student achievement is an important issue for both researchers and stakeholders in educational systems. Although public expenditure has been extensively researched in the context of debates on enrolment, school effectiveness, and government accountability (Baldacci et al., 2004; Tsang and Ding 2005; Ihugba et al., 2019), very little or no research has been conducted on the relationship between household expenditure and enrolment. The primary goal of the current study is to examine families' tertiary education choices in relation to their income, the impact of family expenditure, and existing tuition policies on these choices.

Brief description of Nigeria’s tertiary education

Tertiary education includes all forms of postsecondary formal education, including public and private universities, colleges, technical training institutions, and vocational schools. Tertiary education is critical for promoting growth, alleviating poverty, and increasing shared prosperity. Innovation and growth require a highly skilled workforce that has access to a good postsecondary education for life. People with more education are more likely to get jobs, are more productive, earn more money, and can handle economic changes better. Tertiary education benefits society as a whole, not just the individual. Graduates of tertiary education are more environmentally conscious, have healthier habits, and participate in civic activities at a higher level. Increased tax revenue from higher earnings, healthier children, and smaller family sizes all contribute to stronger nations. In short, tertiary education institutions prepare individuals not only for adequate and relevant job skills but also for active participation in their communities and societies. The economic returns for tertiary education graduates are the highest in the educational system, with an estimated 17% increase in earnings compared to 10% for primary and 7% for secondary education. In Sub-Saharan Africa, where graduates earn an estimated 21% more (World Bank, 2022) than those who did not go to college, these high returns are even bigger. Nigeria's tertiary education is now made up of public and private universities, polytechnics, monotechnics, and education colleges. As of August 2017, the country had 153 universities registered by the NUC (Nigeria University Commission), of which the federal and state governments owned 40 and 45 respectively, 68 were privately owned. According to the Federal Ministry of Education, Nigeria has 43 federal universities, 47 state universities, 75 private universities, 28 federal polytechnics, 43 state polytechnics, 51 private polytechnics, and 152 colleges of education (27 federal, 82 private, and 54 state colleges of education) (Wikipedia, 2022). For example, in Nigeria, the number of students enrolled in tertiary education programs has more than doubled in the last decade. This is critical because, according to a World Bank Group (WBG) report, a student with a tertiary education degree will earn more than twice as much as a student with only a secondary school diploma over their lifetime. As the youth population grows and graduation rates in primary and secondary schools rise dramatically, there is an increasing demand for expanded access to high-quality tertiary education. Tertiary technical and vocational education and training can be an effective and efficient way to give students skills and knowledge that are useful in the job market in addition to traditional university studies.

State and federal governments are increasingly realizing that the entire educational system—from pre-kindergarten to tertiary education—must reflect the new social and economic needs of the global knowledge economy, which increasingly requires a better-trained, more skilled, and adaptable workforce. But there are still problems. Even among the larger group of college graduates, many don't have the locally relevant skills needed for successful integration into the workforce. At the same time, increased enrollment puts a strain on publicly funded institutions of higher learning, and many countries with limited resources are struggling to meet the growing needs of a larger student body without sacrificing the quality of their educational offerings. Tertiary education is also out of reach for many of the world's poorest and marginalized people. In Sub-Saharan Africa, only 9% of people in the traditional age group for tertiary education go from secondary to tertiary education. This is the lowest enrollment rate of any region in the world. The Nigerian government has restructured its tertiary education systems in order to expand their reach and effectiveness. Progress, however, has been uneven. Participating in strategic reforms of the country's tertiary sectors benefits from ensuring that their national strategies and policies prioritize equitable access, improved learning and skill development, efficient retention, and consideration of the employment and education outcomes sought by graduates and the labor market. Policy and academic degrees must both be strategically tailored to meet the needs of the local society and economy. Only then will the government be able to turn gains in primary and secondary education into long-term economic and social growth through access to and progression in tertiary education.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The importance of education in a country's social, political, and economic development is well documented in the literature. Human resources, according to Aliu (2001), determine a country's growth and development. And it has been stated that the primary goal of education in Nigeria is to provide much-needed manpower to accelerate economic growth and development (Schultz, 2002). This belief in the efficacy of education as a powerful development tool has led many nations to commit vast sums of money to the establishment of educational institutions at all levels—primary, secondary, and tertiary. According to Ajayi and Ekundayo (2006), education funding should not be viewed as an expense but as a long-term investment that will benefit society as a whole. Cameron and Heckman (2001) looked at the research on why people go to school and found that a strong link exists between family income and finishing school. The most prevalent explanation of this data is that while choosing a school, teenagers encounter educational funding limitations. Another reason for the favorable association between parental income and educational attainment is that family income has long-term effects. Several studies have revealed a link between family income and other variables of family background and accomplishment in elementary and secondary school test results. This result suggests that parental income, like parental education, influences children's cognitive abilities and educational preferences. The impact of family income and other family characteristics has been demonstrated in many different situations, including those with free tuition and no admission limitations, according to Carneiro and Heckman (2002). Several studies, however, have found family income to be the most influential of all household factors (Behrman and Knowles, 1999; Glick and Sahn, 2000; Orazen and King, 2008). There is controversy concerning the constraints of family income estimates, which include measurement errors associated with utilizing current yearly income. In the literature, it has also been highlighted that household income is disclosed less accurately in surveys than spending. To compensate for this error, some research (Tansel, 1997) has utilized expenditure as a substitute for income. Tansel (2002) revealed, using an ordered probit model and a well-designed dataset encompassing 26256 households in Turkey, that family education spending had a positive connection with school attendance at the elementary, middle, and high school levels. However, this was not a causal conclusion, because test scores were not used as a measure of educational performance in the research. Aside from that, it is often considered that the association between family income and education is favorable (Glick and Sahn, 2000; Lincove, 2009). This is because impoverished families may be unable to pay the direct and indirect expenses of education as well as borrow to meet the expenditures. In general, if a household becomes destitute, its children will not attend school. Indeed, it has been said that one of the key reasons why so many youngsters drop out of school and begin working is because their parents' income is poor (Ray, 2000). While some studies contend that child labor prevents children from fully benefiting from school by increasing opportunity costs, resulting in a decrease in child schooling (Ray, 2000; Lincove, 2009), Patrinos and Psacharopulos (1997) find that in Peru, working allows children to attend school, particularly when parents do not have enough funds to keep their children enrolled. The level of price elasticity in private schools is higher than in public schools. Price sensitivity is higher in poorer families than in affluent ones (Alderman et al., 2001).

In Nigeria, several efforts have been made to scientifically verify the impact of educational expenditure on growth. Akangbou (1983), Mbanefoh (1980), and Anyanwu (1996) are three of these initiatives (1996). Using 1974 to 1975 data from the former Midwestern Nigeria, Akangbou (1983) estimated the crude private average rates of return on education for secondary and postsecondary levels. The expected crude private rate of return for lower secondary schools was 13.4%. The percentages were 11.9, 11.2 and 17.2% for secondary technical schools, upper secondary schools, and universities, respectively. He also computed crude societal average returns for lower secondary, secondary technical, upper secondary, and university levels to be 12.3, 11.0, 10.4 and 12.7%, respectively. His results imply that, regardless of how much money is spent on education, the private and societal returns are always lucrative and reasonable. Investing in education also helps the economy.

Okedara (1985) used the three-year experimental adult literacy program at the University of Ibadan to create the private and societal advantages connected with formal and informal (adult literacy program) elementary education. He calculated the private rate of return on formal elementary education. These values were derived after accounting for economic growth. As a result, both formal and informal elementary education boost productivity not just via wages but also through greater capacity for future earning possibilities, which in turn leads to growth. Mbanefoh (1980) also did a cost-benefit study of university education in Nigeria. His conclusion was that investing in university education at any discount rate between one and ten is always profitable. Because of this, more people in many developing countries want to go to school now that they know how helpful it can be.

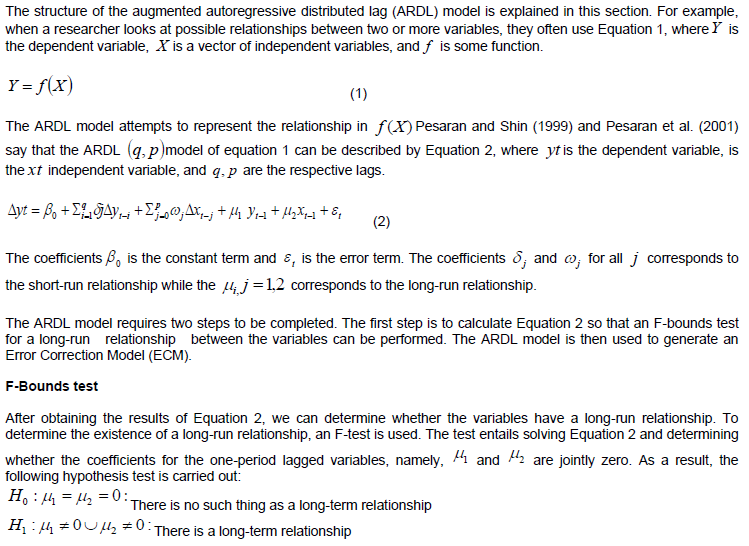

METHODOLOGY

The F-test in the ARDL framework has a non-standard distribution that depends on:

2. The number of independent variables

3. If the model includes an intercept and/or trend term.

The hypothesis test has upper and lower critical value bounds, as well as three different cases. The F-test results are compared to the critical values tabulated by Pesaran et al (2001). If the computed F-statistic is greater than the upper bound, the null hypothesis is rejected, and the existence of a long-run relationship between the variables is evident regardless of the order of integration. The null hypothesis cannot be rejected if the F-statistic falls below the lower bound, and the presence of cointegration is not significant. Finally, the test is inconclusive if the F-statistic falls between the upper and lower bounds (Pesaran et al. 2001):

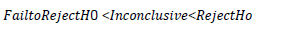

Error correction model

In the case of inconclusive F-bounds test results, Banerjee et al. (1998) and Kremers et al. (1992) proposed testing the error correction term. There are a few assumptions that must be made in order to define an ECM-term. Since the F-bound test gives good results, the long-run equilibrium relationship can be found without using spurious regression. This is because the linear combination of the non-stationary variables is stationary in a simple OLS framework (Haq and Larsson, 2016):

Lag selection

The lag selection, like the unit root tests, is critical because it determines the model's results. There are several methods for determining the best lag for each variable. In the ARDL framework, however, the Schwarz Information Criteria (SIC) provides slightly better estimates than the Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) in small samples (Pesaran and Shin 1999). The AIC criteria also have a tendency to overestimate the number of lags to be included, which is undesirable in small samples because increasing the lag reduces the number of observations. As a result, in order to create a coherent model, the SIC criteria will be used to determine the optimal lag length for both the ADF test and the ARDL model.

Diagnostic tests and stability test

Because the ARDL model seeks the best linear unbiased estimator (BLUE), diagnostic tests are required. Finally, we will use the Breusch-Godfrey serial correlation LM test for residual non- autocorrelation, normality (Jarque-Bera), and stability to see if the model is strong enough (cumulative sum of squares, CUSUM-SQ).

Data source

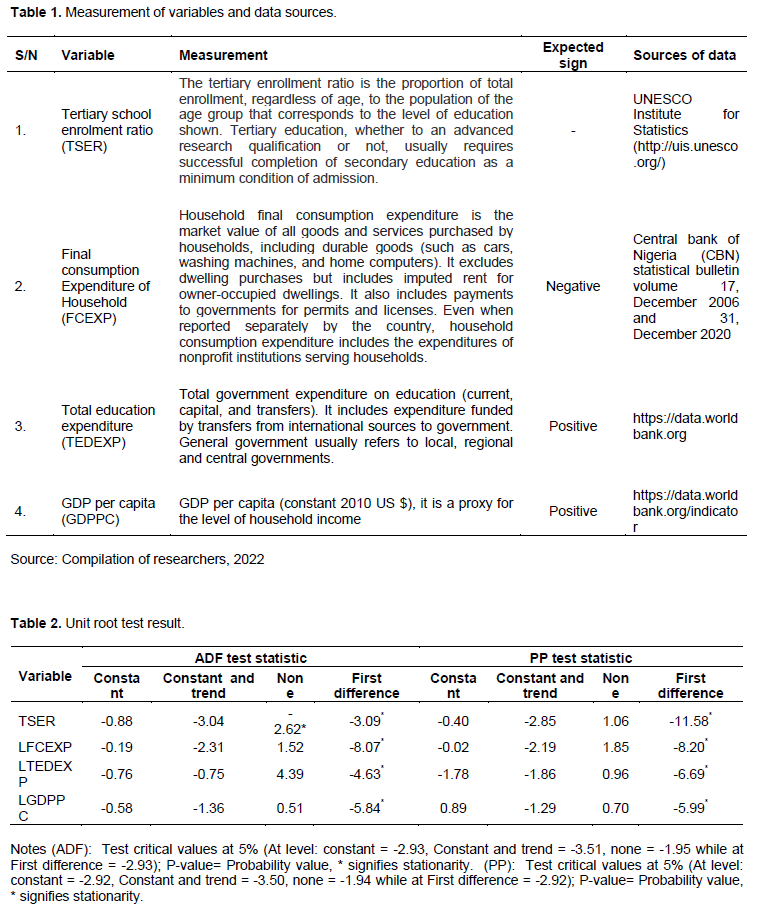

Secondary data from the Nigerian Central Bank and the World Bank were used in the analysis. The study spans the years 1970 to 2020. All-time series data will be converted to a log-log equation. As a result, the coefficient may be considered elastic. Table 1 lists the variables and their sources.

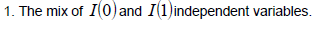

Econometric modeling

It is assumed that parents derive utility from their own consumption of goods (C) as well as from sending their children to tertiary institutions (TR). U = U(C, TR [EXP]), where tertiary institution enrollment is assumed to be determined by household expenditure (EXP). Sending children to tertiary institutions necessitates a sacrifice of current consumption in order to invest in fees and school supplies. Following secondary school graduation, households have three options: learn a skill/trade, look for work, or pursue the first level of tertiary education. At this point, the decisions of households are influenced by their income, household expenditure, and expected future earnings, as well as the expected probabilities of finding a job that corresponds to the tertiary education obtained by the household member. The data are subjected to the ARDL model, and the general equation is presented and explained. The lag selection required for good results is described, as is the specific F-bound test. Following the above description and Equation 2, the applied ARDL model is given in Equation 6, where the tertiary education enrollment ratio is denoted as TSER in the Equations. Except for the tertiary education enrollment ratio, all data is expressed as natural logarithms. The logarithm is used to make it easier to figure out what the results mean and to lower the chance of heteroscedasticity.

The following hypotheses are used to investigate the causation and co-integration of TSER and LFCEXP, LTEDEXP, and LGDPPC: Is there a short-run relationship in Nigeria between TSER and the independent variables? (ii) In Nigeria, is there a long-run relationship between TSER and the independent variables?

Lag determination

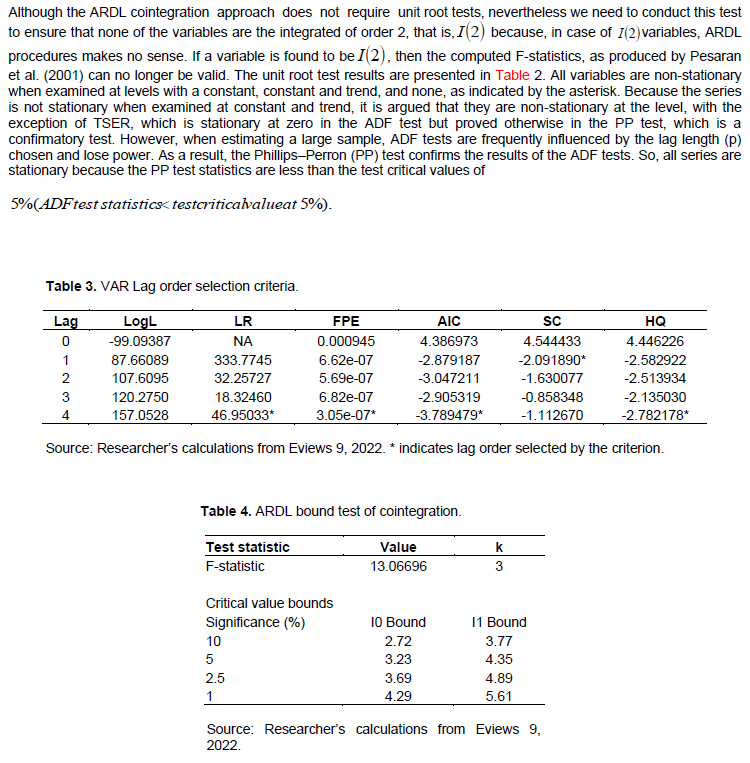

The results of lag-order selection are shown in Table 3. The lag order for the SC, HQ, and FPE selection criteria is one, while the lag order for the AIC selection criteria is four. Because AIC has the lowest value, the investigation will move on to other tests using lags (4).

.png)

Estimation of long-run relationships

To determine whether the variables are cointegrated in the long run, the applicable hypothesis is that there is no long-run relationship, such as:

H0: λ1 = λ2 = λ3 = λ4 = 0 (there is no long-run relationship)

H1: λ1 ≠ λ2 ≠ λ3 ≠ λ4 ≠ 0 (there is a long-run relationship)

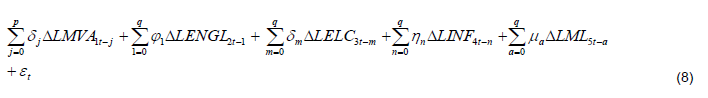

The long-run results are presented in Table 5. The coefficient of final consumption expenditure of a household isFTCEXP in its first and second lags is 2.40 and 2.51, which are both statistically significant, which implies that a 1% increase in the first lag of final consumption expenditure of a household will lead to a 2.40% increase in tertiary education enrollment ratio in the long run. It will increase by 2.51% in the second lag. The coefficient of GDP per capita in its fourth lag is -16.64 and it is statistically significant, which implies that a 1% increase in GDP per capita (proxy for income) will reduce tertiary education enrollment ratio by 16.64% in the long run. The coefficient of total education expenditure in its third lag is 0.54 and it is statistically significant, which implies the effect of government policy on education on tertiary education enrollment in its third lag is a 54% increase in the long run.

.png)

Short-run relationship

The model is specified as follows:

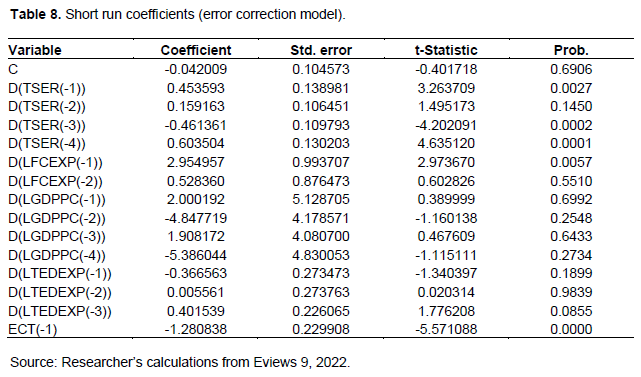

Table 6 displays the short-run results. All of the determinants are clearly statistically significant. Furthermore, the ????−1 coefficient is negative, as expected, and statistically significant. The significance of the lagged error correction term implies that all variables in the tertiary education enrollment model have long-term causality towards consumption and expenditure. The error correction term has an error correction coefficient of around -1.28, indicating that 128 % of the disequilibrium in tertiary education enrollment is corrected annually. To be more specific, it takes a year to correct short-term disequilibrium and restore Nigeria's previous year's shock to return to long-term equilibrium of income and consumption. The error correction model results show that there is a short-term relationship between tertiary education enrollment and household income, household consumption, and the government education policy model. The final consumption spending of households with a lag of one is significant at the 1% confidence level. This shows that there is a short-term cause-and effect link between a household's final consumption spending and the number of people in the household who go to tertiary school.

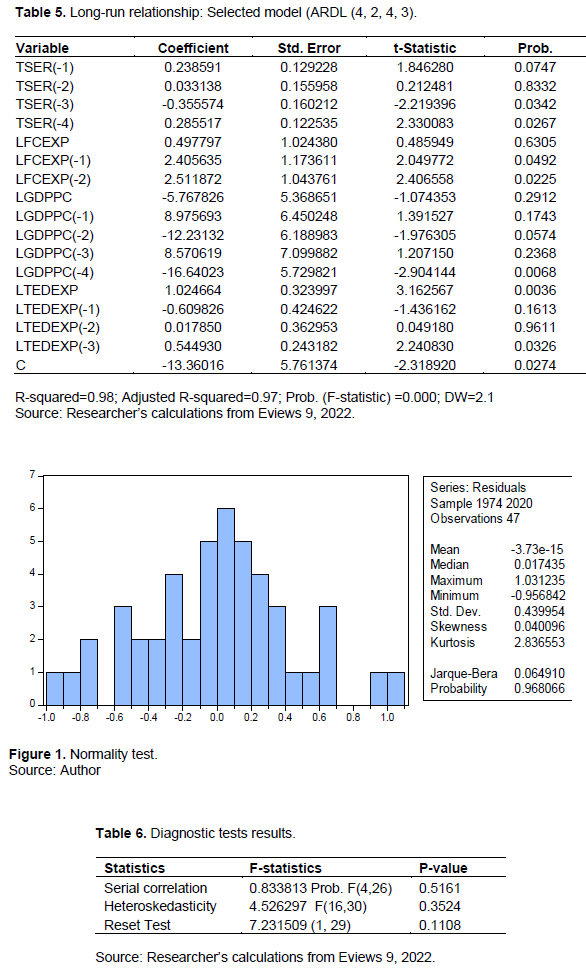

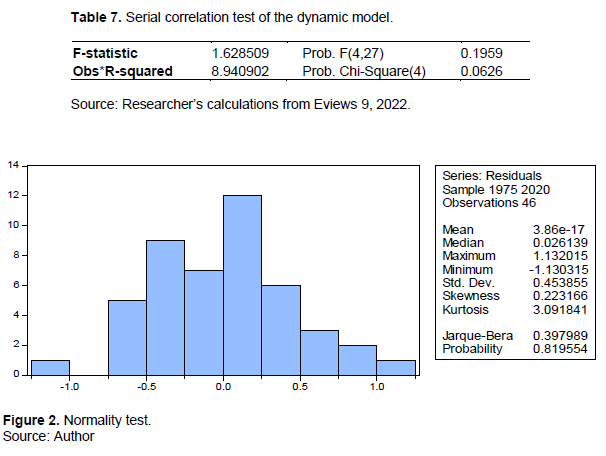

Model checking

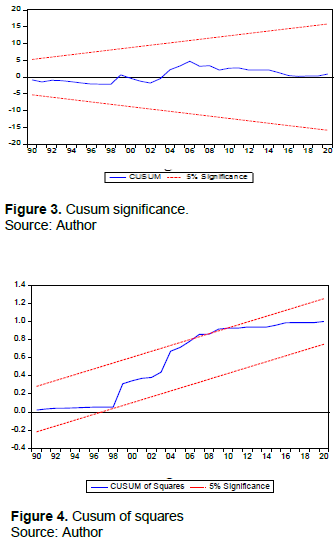

Table 7 demonstrates that there is no serial correlation. Similarly, the normalcy test is carried out. The skewness is 0.22 and the kurtosis is 3.09, as shown in Figure 2. The JB is represented by 0.40 and has a probability value of 0.82, which is significant at a 5% critical value. Figure 3 shows the stability test result, which shows that the Cusum plot test statistic did not cross the 5% critical lines, indicating that the model is stable. Finally, Brown, Durbin, and Evans (1975) propose the cumulative sum of recursive residuals (CUSUM) and CUSUM square (CUSUMSQ) tests to investigate the model's stability. Figures 3 and 4 show that the plot of the CUSUM or CUSUMSQ line do not break the limits. This means that the coefficients are stable.

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

The ARDL test results suggest a positive, significant relationship between final consumption expenditure of a household and tertiary education enrollment in the first and second lags. The significant relationship indicates that final consumption expenditure of households and tertiary education enrollment are related in the short and long run. Changes in Nigerian households' final consumption expenditure explain changes in tertiary education enrollment. It also shows that consumption expenditure of a household gives tertiary education enrollment power; an increase in consumption expenditure of a household increases tertiary education enrollment ratio. The findings also show that the high cost of living reduces the ability of households to train their children and wards in tertiary institutions. The findings back up prior studies by Behrman and Knowles (1999), Glick and Sahn (2000) and Orazen and King (2008) that household income is revealed less accurately in surveys than expenditure when it comes to school enrolment.

Other results are equally interesting. For example, total education expenditure (LTEDEXP) is insignificant and negatively related to tertiary school enrolment in Nigeria, which is not in line with the findings of Baldacci et al. (2004) and Ihugba et.al. (2019). However, the coefficient of household income (proxied by GDP per capita) in its second and fourth lags is significant and negatively related to tertiary school enrollment in Nigeria, which contradicts the findings of Glick and Sahn (2000) and Lincove (2009).The findings support the report of Nigeria's National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) and the Joint Admissions and Matriculation Board (JAMB) as reported by Kazeem (2017) about the disparity between the applicants who sought admission into Nigerian tertiary institutions and the number of tertiary institutions. The large percentage of candidates who don’t get admission into tertiary institutions in Nigeria is not as a result of the income of those that will sponsor them. It is also confirmed by the negative relationship that if the income of households increases, the demand for public tertiary institutions will reduce. Parents choose public institutions because of the cost of schooling. The result of the estimates of the error correction model presented in Equation 2 is reported in Table 8. The estimated error correction model provides information on the short-run relationship among TSER, LFCEXP, LTEDEXP, and LGDPPC. Except for TSER, all of these variables are reported in their (lagged) difference.The one-lagged error-correction term ECTt-1, which measures the disequilibrium between the actual and equilibrium TSER is statistically significant at one per cent level of significance and has the correct sign. According to the estimated coefficient for ECTt-1, ΔTSER takes about 1.28 years (that is, one divided by the estimated coefficient of ECTt-1) to converge to a long-run steady state. Moreover, the estimated results suggest that the model has a reasonable good fit with robust diagnostic tests for error processes such as the absence of serial correlation, stability, and normality. The result presented in Table 7 also shows that the coefficient of the first lag of household expenditure is positively related to tertiary school enrolment and statistically significant. This implies that, holding other variables constant, a percentage change in the lag of household expenditure in the first year will result in a 295% change in tertiary school enrolment. This is consistent with our a priori expectation that increased household expenditure will lead to an increase in tertiary school enrolment.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The study concluded that household expenditure, which measures the standard of living, has a relationship with tertiary school enrolment and is a key determinant of students’ participation in tertiary schools in Nigeria. An increase in household income affects the number of candidates who get admitted into tertiary institutions negatively. The study recommends that the government should establish more tertiary institutions and improve the reputation of the existing ones by funding them adequately.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Ajayi IA, Ekundayo HT (2006). Funding initiatives in university education in Nigeria. In Being a paper presented at the national conference of Nigerian Association for Educational administration and Planning [NAEAP]. Enugu State University of Science and Technology, Enugu State. |

|

|

Akangbou SD (1983). Cost benefit analysis of education investment in Nigeria. Journal of Nigeria Education Research Association 3(2):29-38. |

|

|

Alderman H, Orazem PF, Paterno EM (2001). School quality, school cost and the public/private school choices of low-income households in Pakistan. Journal of Human Resources 36:304-326. |

|

|

Aliu S (2001). The competitive drive, new technologies and employment: the human capital link. A Paper Presented at the Second Tripartite Conference of Manpower Planners. Chelsea Hotel, Abuja. |

|

|

Altbach PG, Knight J (2007). The internationalization of higher education: Motivations and realities. Journal of Studies in International Education 11:290. |

|

|

Anyanwu JC (1996). Empirical evidence on the relationship between human capital and the income of Nigerian women. Journal of Economic Management 3(1). |

|

|

Baldacci E, Maria TG, Luiz de Mello (2004). Social spending, human capital, and growth in developing countries: Implications for achieving the MDGs, IMF Working Paper, no. wp/04/217, Washington DC. |

|

|

Banerjee A, Dolado J, Mestre R (1998). Error-correction mechanism tests for cointegration in a single-equation framework. Journal of Time Series Analysis 19(3):267-283. |

|

|

Behrman JR, Knowles JC (1999). Household income and child schooling in Vietnam. The World Bank Economic Review 13(2): 211-256. |

|

|

Cameron SV, Heckman JJ (2001). The Dynamics of educational attainment for black, Hispanic, and white males. Journal of Political Economy 109:455-499. |

|

|

Carneiro P, Heckman J (2002). The Evidence on Credit Constraints in Post-secondary Schooling, Economic Journal 112(482):705-734. |

|

|

Glick P, Sahn DE (2000). Schooling of girls and boys in a West African Country: The Effects of parental Education. Income and Household Structure. Economics of Education Review 19:63-87. |

|

|

Haq S, Larsson R (2016).The dynamics of stock market returns and macroeconomic indicators: An ARDL approach with cointegration. KTH Industrial Engineering and Management, IndustrialManagement, Stockholm, Sweden. Obtidoem 15 de Março de 2020, de |

|

|

Ihugba OA, Ukwunna JC, Obiukwu S (2019). Government education expenditure and primary school enrolment in Nigeria: An impact analysis. Journal of Economics and International Finance 11(3):24-37. |

|

|

Kazeem Y (2017). Only one in four Nigerians applying to university will get a spot. Accessed from View |

|

|

Kremers JJ, Ericsson NR, Dolado JJ (1992). The power of cointegration tests. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 54(3):325-348. |

|

|

Lincove JA (2009). Determinants of schooling for boys and girls in Nigeria under a policy of free primary education. Economics of Education Review 28:474-484. |

|

|

Luhanga ML, Mkude DJ, Chijoriga MM, Ngirwa CA (2003). Higher education reforms in Africa: The university of Dar es Salaam experience. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: Dar es Salaam University Press. |

|

|

Makulilo V (2012) Disconcerted success of students' loans in financing higher education in Tanzania, African Review 41(2):108-135. |

|

|

Mbanefoh GF (1980): Sharing the costs and benefits of university education in Nigeria. A suggested approach. The Nigerian Journal of Economics and Social Studies 22(1):67-84. |

|

|

Okedara JT (1985). Cost-benefits analysis of education investment in Nigeria. The Nigerian Journal of Economics and Social Studies 38(3):219-234. |

|

|

Orazen PF KingEM (2008). Schooling in developing countries: the roles of supply, demand and government policy. Handbook of Development Economics 4:3476-3559. |

|

|

Patrinos HA, Psacharopoulos G (1997). Educational performance and child labour in Paraguay.International Journal of Educational Development 15(1):47-60. |

|

|

Pesaran MH, Shin Y (1999). An autoregressive distributed lag modelling approach to cointegration analysis. In: Strom, S. (Ed.), Econometrics and Economic Theory in 20th Century: The Ragnar Frisch Centennial Symposium. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge Chapter P 11. |

|

|

Pesaran MH, ShinY, Smith RJ (2001). Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of Level relationships. Journal of Applied Econometrics 16:289-326. |

|

|

Phillips PC, Perron P (1990). Testing for a unit root in time series regression, Biometrika 75:335-346. |

|

|

Ray R (2000). Child labour, child schooling and their interaction with adult labour: Empirical evidence for Peru and Pakistan The World Bank Economic Review14(2):347-67. |

|

|

Schultz TP (2002). Why governments should invest more to educate girls. World Development 30(2):207-255. |

|

|

Tansel A (1997). School attainment, parental education and gender in Cote D'Ivoire and Ghana. Economic Development and Cultural Change 45(4):825-56. |

|

|

Tansel A (2002). Determinants of school attainment of boys and girls in Turkey: Individuals, Households and Community Factors. Economics of Education Review, 2 and Ding, Y. (2005). Resource utilization and disparities in compulsory education in China. China Review 1-31. |

|

|

Tsang MC, Y. Ding (2005) "Resource Utilization and Disparities in Compulsory Education in China", China Review 5(1):1-31 |

|

|

Xu JW, YXR (2014). Can the increase in public expenditure on education alleviate the second-generation phenomenon? An analysis of intergenerational income mobility based on CHNS. Journal of Finance and Economics 40(11):17-28. |

|

|

Wikipedia (2022). Education in Nigeria. Accessed from |

|

|

World Bank (2002). Higher education. Accessed from |

|

|

Yu Z (2017). Can Higher Household Education Expenditure Improve the National College Entrance Exam Performance? Empirical Evidence from Jinan, China. Current Issues in Comparative Education 19(2):8-32. |

|

|

Zhou ZY (2001). Education, social stratification and social mobility. Journal of Beijing Normal University Social Sciences 1(5):85-91. |

|

Copyright © 2024 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article.

This article is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0