ABSTRACT

Work-life balance has always been concerned with those interested in the quality of working life and its relation to broader quality of life. This study sought to establish the influence of characteristics of work-life balance on teachers’ levels of job satisfaction in public secondary schools in Nairobi County, Kenya. The purpose of this study was to determine the influence of supervisor support and gender on the teachers’ levels of job satisfaction. The study used Stacy Adams’ equity theory of which holds that individuals compare their ratio of inputs and outcomes to the input-outcomes of other individuals. This study was a descriptive survey design. The target population was 83 public secondary schools and 1759 public secondary school teachers’ with 67 principals and 670 teachers sampled. Data were collected using an interview schedule and questionnaires. Descriptive statistics was performed to analyze quantitative data. Pearson Product Moment Correlation Coefficient was used to determine the linear correlation between the independent variables and the dependent variable. Using null hypotheses, multiple regression analysis was done. The key findings were that the principals were supportive to their teachers especially in terms of readily giving them permission to attend to their personal needs and training opportunities. There was no statistically significant difference in teachers’ levels of job satisfaction between male and female teachers. The study recommends that the Teachers Service Commission should formulate policies that are specifically geared towards enhancing teachers’ work-life balance. Comparative studies should be carried out in the rural areas.

Key words: Gender, influence, job satisfaction, supervisor support and work-life balance.

In this world, for one to have an enjoyable and stress-free life, balance is essential (Marmol, 2019). The term work-life balance gained importance in the late 1960s, due to concerns about the effects of work on the general employees’ wellbeing (Leovaridis and Vatamanescu, 2015). According to Tanvi and Fatima (2012), work-life balance is the perception that human beings attach equal importance to their employment life as well as their private life. Subha (2013) defines work-life balance as the reconciliation between workers’ professional work and their personal life. Muhtar (2012) noted that globally, work-life balance is considered; as the second most essential workplace aspect. Bloom et al. (2002) assert that whereas initially work was a matter of survival and necessity, today work is not only still considered as a necessity but a source of satisfaction as well.

Fisher and Layte (2003), consider three distinct sets of measures of work-life balance proportion of free time, the overlap of work and other dimensions of life and the time spent with other people. Singh (2013) posits that work-life has grown in popularity since it stands for a crucial drive for societal prosperity and fulfillment and growth of every worker and every company. However, Murphy and Doherty (2011) reckon that it is not possible to measure work-life balance in an absolute manner. This is because work-life balance is influence by numerous personal circumstances and therefore the perception of balance or imbalance is a reflection of an individual’s priorities. They argue that what matters most is for the employees to draw a distinction between their work and personal life and ensure that the line is in the right place.

Job satisfaction can be defined as how content an individual is with their job (Bloom et al., 2002). It is regarded, as the state of being emotionally positive in reaction and attitude towards one’s own work. Job satisfaction is a general expression of workers’ positive attitudes built up towards their jobs (Celik, 2011). According to Bradey (2001), job satisfaction is an emotional effective response derived from one’s job. These feelings are not limited to salaries but include factors like the way the employees are treated and how the management regards their input. When a balance is struck between work and life, workers become more effective and enjoy doing their jobs, (Akbar and Hafeez, 2015). Many teachers are dissatisfied with poor relations with colleagues, time allocated for planning and teaching, working conditions and the general school environment (Meyer and Turner, 2007). Unfortunately, in many third world countries, teachers’ job satisfaction has not been given the attention it deserves. This has seen many teachers leave the profession, increased teacher absenteeism, rise in student indiscipline and general teacher underperformance (Khan, 2004). In Malawi, for instance, teachers were found to be highly dissatisfied with remuneration and poor working conditions (Kadzamira, 2000). Similarly, in Nigeria, teachers were found to be agitating for better salaries but the Ministry of Education could not meet this because of inadequate resources (Nwachukwu, 2016). The recent past has witnessed the government of Kenya pass a policy that requires a teacher to stay in the same station for at least five years before they can apply for a transfer. This has resulted into opposition by teachers unions, specifically the Kenya National Union of Teachers (KNUT) and the Kenya Union of Post Primary Education Teachers (KUPPET).According to these unions, this policy infringes on the teachers’ professional freedom and the right of choice (Sirima and Poipoi, 2010).

Work-life balance depends on supervisory support that employees receive. This is the deliberate support offered by the supervisor to employees to enable them perform their duties well and attend to personal or family needs effectively as well (Straub and Hagiwara, 2011). It entails the understanding and concerns that the supervisors have over employee’s wellbeing both at work and at home (Ryan and Kossek, 2008). Supervisors are agents of the organization and their feedback to employees is often considered as the organization’s orientation towards them (Eisenberger and Stinglhamber, 2011).A supportive supervisor is understanding, provides valuable resources, is flexible and increases employees’ confidence (Thornhill and Saunders, 2008). Okoth (2008) also found that there was a positive correlation between instructional supervision and curriculum implementation and when such implementation is performed well, teachers are motivated to implement the curriculum in an appropriate manner. According to Wachira et al. (2016), majority of teachers derive job satisfaction from the support they get from their supervisors as they perform their tasks. This support included involvement in decision-making and incentives from the supervisor.

Female professionals have different sets of demands and when such role demands overlap, many problems arise. Times have changed. It is no longer the husband earning and the wife staying at home. Today the husband earns and the wife earns too. However, the wife still takes primary responsibility to run the house (Aeran and Kumar, 2015; Muasya, 2016). Lakshmi and Kumar (2011) posit that female teachers especially in private teaching institutions face numerous challenges. Often, as full time workers, they have to carry some work home. Women who hold positions of responsibility tend to experience more work-family conflicts (Parasuraman et al., 2001).

Good work-life balance is important for a teacher’s effectiveness and job satisfaction and leads to better student learning. It also improves the wellness of the institution and student behaviour. Moreover, other than giving a feel of job satisfaction it also helps to achieve higher retention rates in learning institutions (Laksmi and Kumar, 2011). Perry et al. (1997) argue that during one’s teaching career, a teacher encounters challenges in trying to achieve a balance between personal and professional life due to lack of clear boundary between work and personal life. In fact, the past decades have witnessed an increase in the levels of stressors in academia. In a tight labour market with a shortage of needed skills, employers are force to develop policies, which can attract and retain groups of workers who might have previously left the organization (Mukururi and Ngari, 2014). According to study done by Strathmore Business School in 2012, many organizations in Kenya lack policies that support the well-being of their employees beyond their work place.

In Kenya, the subject of work-life balance and its family-friendly policies are still at the nascent stage (Muasya, 2014). Existing studies on work-life balance in Kenya (Sang, 2011; Strathmore Research and Consultancy Centre, 2012; Kangure, 2014) have concentrated on industrial and not educational organizations. These findings are not generalized to educational institutions because corporations operate in different set ups compared to educational institutions. For instance, they run 24 h a day and an employee may easily derive job satisfaction from their remuneration. On the other hand, schools usually operate in the day and a teacher may get job satisfaction when the learners pass exams.

Most studies have always dwelt on what can be done to improve the teacher’s professional life and not their personal life. The Kenyan government froze employment of teachers in 1998. It then introduced Free Primary Education (FPE) in 2003 and later, subsidized secondary education in 2008. The latter saw an upsurge of the number of learners in both primary and secondary schools. Since then, teachers have more workload and less time for their personal lives. Leshao (2008) asserted that teachers felt that the introduction of FPE was without sufficient preparation. To redress this, the government has been employing teachers to replace those who have left the service (Sirima and Poipoi, 2010). The Kenya Secondary Schools Heads Association (KESHA) and the Kenya National Union of Teachers (KNUT) in 2011 estimated teachers’ shortage to have been at 79,295 with a high pupil- teacher ratio (55:1) in public secondary schools (Daily nation, 25th January 2011). Moreover, the Teachers Service Commission, besides providing teachers with statutory leaves, does not have any other formal family-friendly policies (Muasya, 2016). Nairobi being the capital city of Kenya attracts public secondary school teachers in big numbers because it has many social amenities and career advancement opportunities. In fact, the TSC seldom advertises teaching vacancies in Nairobi. It was imperative against this background to carry out a study on the influence that work-life balance practices have on public secondary school teachers in Nairobi.

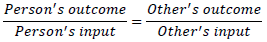

This study adopted the equity theory of motivation propounded by Stacy Adams in 1963. According to this theory, individuals compare the ratio of their inputs and outcomes to the input-outcomes of other individuals. Inputs include age, educational qualifications, working experience, effort expended in the work among others. Outcome variables include pay, promotion, leave time and interest in the job. The individuals also compare what they offer as service and what they get in return as remuneration. This ratio is represented as follows.

In the educational setting, teachers in Kenya compare the supervisory support and duties assigned to male and female counter parts with those in the civil service with similar qualifications. If from the comparison, the teachers think that they are disadvantaged they feel dissatisfied. Teachers in day schools go home as early as four in the evening and report to work around seven in the morning. In this regard, teachers in boarding schools and especially those with evening and early morning duties have very long working hours. They often feel disadvantaged over their colleagues in day schools or even in the public service.

Proposed research hypotheses

H01: There is no significant influence of supervisor support on levels of job satisfaction among public secondary school teachers in Nairobi County.

H02: There is no significant difference in the performance of teaching responsibilities between male and female teachers and their levels of job satisfaction among public secondary school teachers in Nairobi County.

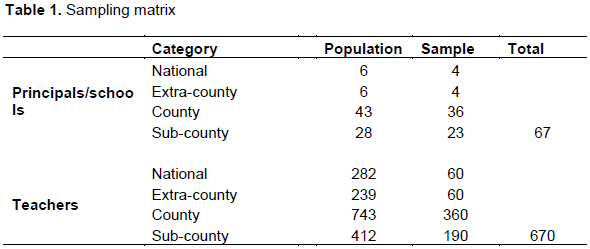

This research used descriptive survey design that is concerned with describing the characteristics of a particular individual or of a group (Kothari, 2019). This study targeted 83 public secondary schools and 1759 public secondary school teachers in Nairobi County (County Director of Education Office, 2019). The study used a response ratio of 80.7% achieved with simple random sampling. The sampling matrix is as shown in Table 1.

This study used questionnaires to collect primary data from the teachers and an interview schedule for the principals. To achieve face validity, the study adapted variables used in similar studies (Kangure, 2014; Subha, 2013).To determine content validity, the researcher ensured that the questions were clear and not ambiguous and in line with the study objectives. The questionnaires and the interview schedule were subjected to expert and professional judgment of the supervisors as recommended by Best and Kahn (2006). A pilot study with 12 teachers was carried out as recommended by Julious (2005). To ensure reliability, the test-retest method was used and the alpha value was at 0.715. The data were analyzed using quantitative as well as qualitative methods. In fact, Hejase et al. (2012) contend that informed objective decisions are based on facts and numbers, real, realistic and timely information. Furthermore according to Hejase and Hejase (2013), “descriptive statistics deals with describing a collection of data by condensing the amounts of data into simple representative numerical quantities or plots that can provide a better understanding of the collected data”(272). Therefore, descriptive statistics-using Microsoft Excel was done. Data were reported using frequencies, percentages, means, standard deviation and variance. Pearson’s Product Moment Correlation Coefficient was use to determine the linear correlation between the independent variables and the dependent variable. Furthermore, regression analysis was used to test proposed null hypotheses.

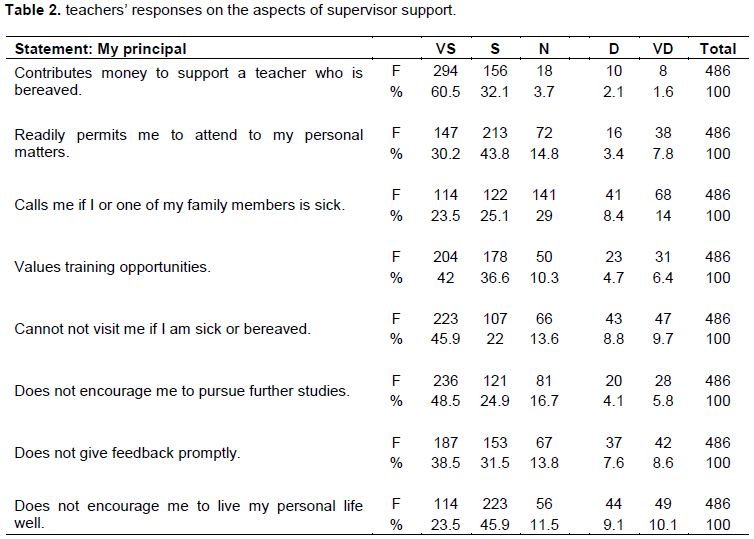

This study sought to establish the influence of characteristics of work-life balance on teachers’ levels of job satisfaction in public secondary schools. Descriptive statistics of Likert scale questions ar reported in Table 2.

Descriptive statistics

Teachers’ attitude towards supervisors’ support

Majority of teachers (92.6%), very satisfied and satisfied agreed that their principal contributed money to help a bereaved teacher. Such feelings from teachers help to show their satisfaction with the supervisor’s support. This resonates well with Mohamed and Ali (2016) who asserted that employees with good support from their supervisors view their employers as generally caring about their well-being and this leads to affective commitment to the organization. On the second aspect, 74% of the teachers were satisfied that their principals readily permitted them to attend to their personal matters. These findings concur with those of Muasya (2016) who found that permission to attend to personal matters was the greatest form of instrumental support teachers received from the supervisor. Furthermore, 33.3% (14 out of 42) of the interviewee principals that were interviewed said that every teacher had one free afternoon to attend to their personal matters.

In spite of many responsibilities the principal has, as confirmed by Afolabi and Loto (2008) and Kieleko et al. (2017), the principal had time to call and even visit teachers in times of sickness or bereavement. However, only 48.6% of the participants agreed to the afore-mentioned. Nevertheless such low percentage may affect their job satisfaction positively as established by Sirima and Popoi (2010) and Anderson et al. (2002) who concluded that a supervisor who is more understanding during family crisis helps to alleviate work-family conflicts. In addition, 78.6% of the principals valued training opportunities, a fact that helps increase the teachers’ engagement in their schools and jobs. In addition, 67.9%agreed that the principal did not give feedback promptly. This is similar to what Kodavatinganti and Reddy (2019) in their study found out, that most teachers were yearning for personal and confidential feedback from their supervisors. This was necessary to maintain the teachers’ dignity among their colleagues as well as students. Such feedback also motivates the teachers, boosts their morale as well as improving their relationship with their supervisors (Anseel and Lievens, 2007).

69.4% of the teachers (23.5% were very satisfied and 45.9% were satisfied with the statement) said that the principal did not encourage them to live their personal lives well. This resonates well with the responses that the principals gave. Only four out of forty two indicated that they talked to the teachers who had challenges balancing between work and personal life.

Principal number 19 said, “Personal lives should not interfere with the school work. However, where one is not able to balance the teacher is talked to.” “Life is a personal choice. Teachers who choose to live their personal lives well do so. Those who don’t, is up to them,” remarked principal number 26.

These findings concur with those Muasya (2015) who established that some supervisors, according to some teachers, were not even aware of the work-life balance challenges that their teachers were undergoing. This ignorance could be a result of lack of sensitivity training on the part of the supervisor. However, some teachers also feel that managing work-life balance is their personal responsibility and therefore the supervisor should not be involved in it.

Performance of teaching responsibilities by gender and job satisfaction

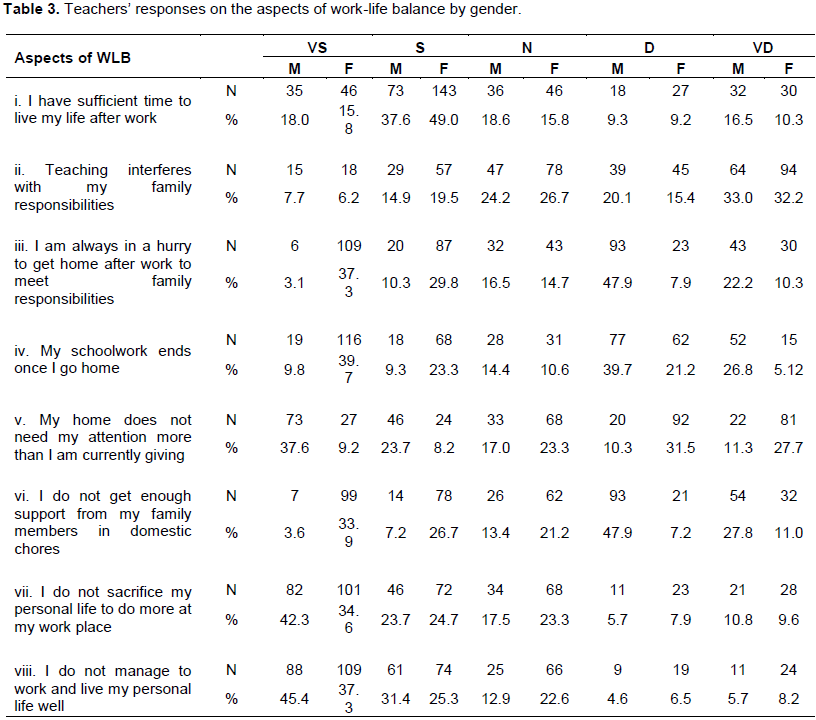

In the past teaching was primarily a domain for women. Not anymore today as both male and female cherish the profession (Punia and Kamboj, 2013). Table 3 shows the findings of teachers’ levels of job satisfaction given their responsibilities by gender.

From Table 3, most teachers, both male (55.6%) and female (64.8%) agreed that they had enough time to live their life after work. This shows that majority of the teachers had sufficient time after work to live their life. Given that there were more female (292) than male (194) teachers in the study, the difference in gender did not significantly matter on how much time the teachers had to live their life after work. These findings are similar with previous studies that established that female and male teachers almost enjoyed equal amount of work-life balance (Bennell and Akyeampong, 2007; Punia and Kamboj, 2013; Aliakbari and Kafshgar, 2013). Furthermore, 56% (24 out of 42) of the interviewee principals said that they assigned duties to teachers equally, irrespective of their gender. However, many more quickly added that they also considered one’s ability and willingness to work. There were more male teachers (53.1%)) than female teachers (47.6%) who said that teaching did not interfere with their family responsibilities. On the other hand, there were more female teachers (25.7%) than male teachers (22.6%), who said that teaching interfered with their family responsibilities. These findings agree with those of Uddin et al. (2013) who researching on female teachers of private schools in Bangladesh found out that teaching interfered with 59%of the female teachers’ family responsibilities. The findings also agree with those of Walker, Wang and Redmond (2008) and those of Maeran et al. (2013) who asserted that women teachers more often had difficulties in balancing their work and home roles. This result is more for of the teachers working in private schools. Some private schools demand a lot more of their teachers’ input even to the detriment of their personal lives.

67.1% of the female teachers versus 13.6% of the male teachers agreed that they were always in a hurry to get home after work to meet family responsibilities. However, 70.1% of the male teachers versus 18.2% of the female teachers disagreed that they were always in a hurry to get home after work to meet family responsibilities. This is because female teachers do most of the household chores. These findings concur with Anuradha (2015) who concluded that in Coimbatore, India, female teachers were more needed at home as compared to male teachers were. Muasya (2015) found out that many female teachers in Kenyan urban schools did not even get enough sleep as they had to do a lot of preparations in the morning and in the evening as well. The aforementioned fact obliges female teachers to be more in a hurry than male teachers to get home after work. Also 36% (15 out of 42) of the principals indicated that female teachers required more time to be with their families. Principal number 3 said, “Ladies with young ones need to go home early for obvious chores.” “Female teachers need more time to attend to their families,” said principal number 12.

Principal number 41 shared similar sentiments by saying, “Female teachers sometimes may require more personal time if they have young babies.”

63.0% of the female teachers said that their schoolwork ended once they got home as compared to 19.1% of the male teachers. On the other hand, 66.5% of the male teachers versus 26.3% of the female teachers said that their schoolwork did not end once they got home. This is an indication that more male than female teachers can do schoolwork in the house like marking or making schemes of work. Shernoff et al. (2011) found out that many teachers, both male and female, often carried their duties like marking and grading home to continue even over the weekend. Meanwhile, less female teachers do schoolwork at home since they have more domestic chores at home than male teachers. Women are primary caretakers of the family.

Moreover, 63.1% of the male teachers versus 17.4% of the female teachers said that their homes did not require more attention than they were currently giving. On the other hand, 59.2% of the female teachers versus 21.6% of the male teachers said that their homes required more attention than they were currently giving. This shows that the female teachers are already giving a lot of attention such that their homes should not be expecting more. These results support Asher (2011) who found out that across all nations, irrespective of the number of hours women spent in paid employment, they still had a “second shift” at home in giving childcare, doing domestic chores and attending to other family related issues. Daly and Lewis (2000) also had similar findings that women work part-time sparing time for family responsibilities. Meanwhile majority of men are not ready to help in accomplishing domestic chores because of cultural norms (Coltrane, 2000). Andrews and Wilding (2014) also found out that quite often-female teachers were overburdened with school workload, personal obligations and daily family responsibilities. Muasya (2015) had similar findings that Kenyan women continue to bear disproportionate share of childcare and domestic chores.

Furthermore, 60.6% of the female teachers (33.9% were very satisfied and 26.7% were satisfied) versus 10.8% of the male teachers (3.6% were very satisfied and 7.2% were satisfied) said that they were not getting enough support from their family members in the performance of domestic chores. On the other hand, 75.7% of the male teachers (47.9% dissatisfied and 27.8% very dissatisfied) versus 18.2% of the female teachers (7.2% dissatisfied and 11.0% very dissatisfied) were getting enough support from their family members. These findings agree with those of Barik (2017) who found that female teachers worked more at home than male teachers did. They tried to alleviate their situation by getting house support from children, parents, in-laws, servants and even their husbands. They also chose to teach in nearby schools in order to save on travelling time. On the other hand, 66% of the male teachers versus 59.3% of the female teachers said that they did not sacrifice their personal life to do more at the work place. These findings concur with those of Uddin et al. (2013) who found out that 68% of the teachers, both males and females, in Bangladesh managed the demands of work and life. These findings are an indication that despite the many responsibilities teachers have, many of them still valued their personal life. From these results, there was no significant difference between male and female teachers’ responses on the statement “I don’t sacrifice my personal life to do more at my work place”.

Cross-tabulation

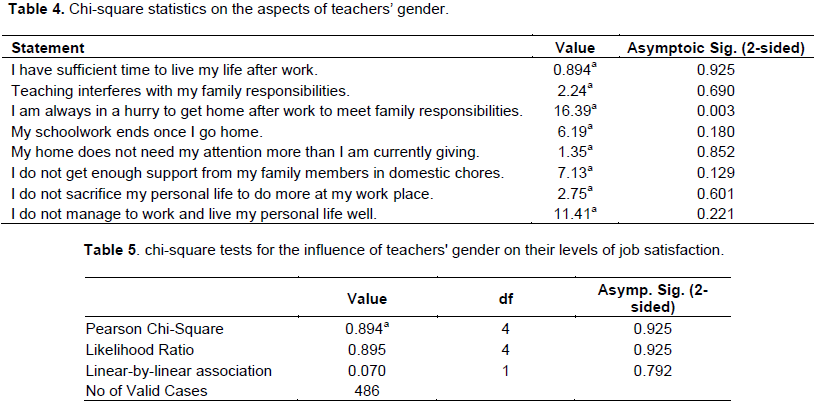

Cross tabulation was performed on various aspects on teachers’ gender to determine whether there was any significant difference between male and female teachers’ levels of job satisfaction. Table 5 shows the Chi-square statistics.

From Table 4, out of the eight aspects on teachers’ gender, four of them showed that there was no significant difference between male and female teachers’ levels of job satisfaction. The statement “I have sufficient time to live my life after work” was highly significant at 0.925. This means that both male and female teachers were satisfied that they had time to live their life after work. Similarly, there was no significant difference between the two genders on the statement “My home does not need my attention more than I am currently giving”. This statement was also highly significant at 0.852. The statement “Teaching interferes with my family responsibilities” at significant level of 0.691 also showed that there was no significant difference between male and female teachers’ level of job satisfaction on this aspect. The results also showed that there was no significant difference between male and female teachers’ levels of job satisfaction on the statement “I do not sacrifice my personal life to do more at my work place”. This statement was significant at 0.601.

However, there was significant difference between male and female teachers’ levels of job satisfaction on the following statements: “I am always in a hurry to get home after work to meet family responsibilities” at p-value of 0.003. As earlier mentioned, majority of female teachers (40.4%) agreed with this statement compared with only 5.4% of male teachers.

Similarly, at p-value of 0.129, there was a significant difference between male and female teachers’ levels of job satisfaction on the statement “I do not get enough support from family members in domestic chores”. Majority of female teachers supported this statement. Another aspect that showed significant difference between male and female teachers’ levels of job satisfaction was on the statement, “My schoolwork ends once I go home”. At p-value of 0.180, more female teachers agreed with this statement than male teachers. Finally, the statement “I do not manage to work and live my personal life well” also showed that there was significant difference between male and female teachers’ levels of job satisfaction at p-value of 0.221. Table 5 shows the Chi-Square test.

From Table 5, the p-value .925 is greater than the standard alpha value (.05) and so the null hypothesis was not rejected. Thus, H02: There is no statistically significant difference in the performance of teaching responsibilities between male and female teachers and their levels of job satisfaction among public secondary school teachers in Nairobi County.

Regression analysis

Linear regression was carried out to evaluate both null hypotheses. The first hypothesis was tested to determine if there was any significant influence of supervisor support on the levels of teachers’ job satisfaction (α = 0.05 level of significance). Table 6 shows a summary of the linear regression analysis.

H01: There is no significant influence of supervisor support on levels of job satisfaction among public secondary school teachers in Nairobi County. The second hypothesis was tested using linear regression. The hypothesis was:

H02: There is no significant difference in the performance of teaching responsibilities between male and female teachers and their levels of job satisfaction among public secondary school teachers in Nairobi County. The results are as shown in Table 7.

H02: There is no significant difference in the performance of teaching responsibilities between male and female teachers and their levels of job satisfaction among public secondary school teachers in Nairobi County.

According to Table 7, the significance level was at 0.155 (p > 0.05). Hence, the null hypothesis that there was no significant difference in the teachers’ performance of duties according to their gender and their levels of job satisfaction was not rejected.

Regression analysis for combined independent and dependent variables

This study wanted to establish a possible regression model to predict the relationship between the combined independent variables and the dependent variable. The results are depicted in Table 8. The relationship between supervisor support and teacher’s gender with the levels of teachers’ job satisfaction was tested through multiple regression analysis. The results from Table 8 show that the F value (15.950) was significant at 0.000 (p<0.05). Therefore, the regression model is a good fit to the given data. In addition, the multiple regression analysis results were further used to determine the influence of each of the two independent variables (supervisor support and teacher’s gender) on the teachers’ levels of job satisfaction. The results are shown in Table 9. Table 9 shows the overall model indicating that supervisor support was highly significant at p=0.000 (1% significance). However, teachers’ gender was significant at p=0.093 (10% significance).

The findings show that the principal’s support to teachers, especially financial support during bereavement, readily granting permission to teachers to attend to their personal needs and supporting teachers to benefit from training opportunities were most appreciated by the teachers. However, the teachers expect the principals to give feedback promptly and to encourage them more to live their personal life well. In terms of gender, both male and female teachers manage to cope with their responsibilities. Assigning teachers duties especially co-curricular ones should be done based on interests and abilities but not necessarily gender. Most teachers finish schoolwork at school and go home to live their personal life.

The Teachers Service Commission should formulate statutory policies that promote teachers’ work life balance. Besides the various types of leave that teachers are entitled to, the TSC should consider providing guidelines on how the already overworked teacher can find time to live his or her personal life better.

Principals need to make deliberate effort to sensitize teachers to live their personal life well. They should abandon the attitude that teachers are free to choose how to live their personal life. This could involve, occasionally, having sessions where professionals in matters work life balance talk to teachers.

The authors have not declared any conflicts of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Aeran A, Kumar R (2015). Impact on Life of Women Employees in Education Sector. Indian Journal of Scientific Research 6(1):57-62.

|

|

|

|

Afolabi FO, Loto AB (2008). The Headmaster and Quality Control in Primary Education Through Effective Intra-School Supervision in Niogeria. Lagos: Krep Publishers.

|

|

|

|

|

Akbar W, Hafeez U (2015). Impact of Work-life balance on Job Satisfaction Among School Teachers of 21st Century. Australian Journal of Business and Management Research New South Wales Research Centre Australia 4(11):27-32.

|

|

|

|

|

Aliakbari M, Kafshgar NB (2013). On the Relationship between Teachers' Sense of Responsibility and their Job Satisfaction: The Case of Iranian High School Teachers. European Online Journal of Natural and Social Sciences 2(5):34-45.

|

|

|

|

|

Anderson SE, Coffey BS, Byerly RT (2002). Formal Organizational Initiatives and Informal Workplace Practices: Links to Work-Family Conflict and Job-Related Outcomes. Journal of Management 8(12):787-810.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Anseel F, Lievens F (2007). The Long-Term Impact of the Feedback Environment on Job Satisfaction: A Field Study in a Belgian Context. Applied Psychology: An International Review 56(2):254-266.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Asher R (2011). Shattered: Modern Motherhood and the Illusion of Equality. London: Random House.

|

|

|

|

|

Bennell P, Akyepong K (2007). Teacher Motivation in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. Lagos: DFID Department of International Development.

|

|

|

|

|

Best JW, Kahn JV (2006). Research in Education. (10th Ed.). New Jersey: Pearson Education.

|

|

|

|

|

Bloom N, Kertschmer T, Reene JV (2002). Georgia Institute of Technology Human Resource Department.

|

|

|

|

|

Bradey DB (2001). Correlates of Job Satisfaction among California School Principals. LA, California USA.

|

|

|

|

|

Celik M (2011). A Theoretical Approach to the Job Satisfaction. Polish Journal of Management 4(1):7-14.

|

|

|

|

|

Eisenberger R, Stinglhamber R (2011). Perceived Organizational Support: Fostering Enthusiastic and Productive Employees. Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Fisher K, Layte M (2003). Measuring Work-Life Balance and Degrees of Sociability. Dublin, Ireland.

|

|

|

|

|

Julious SA (2005). Sample size of 12 per Group Rule of Thumb for a Pilot Study. Pharmaceutical Statistics 4(4):287-291.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kadzamira E (2000). Teacher Motivation and Icentives in Malawi. International Journal of Educational Development 29(3):501-516.

|

|

|

|

|

Kangure FM (2014). Relationship Between Work-Life Balance and Employee Engagement in State Corporations in Kenya. Nairobi, Kenya: Unpublished PhD Thesis, Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology.

|

|

|

|

|

Khan T (2004). Teacher Job Satisfaction and Incentive: A Case Study of Pakistan. Journal of International Academic Research 2:45-56.

|

|

|

|

|

Kodavatiganti K, Reddy P (2019). Impact of Feedback Environment on Teachers' Job Satisfaction. International Journal of Research in Economics and Social Sciences 9(1):49-62.

|

|

|

|

|

Kothari CR (2019). Methods and Techniques: Research Methodology 4th Edition. New Delhi: New Age International Publishers Ltd.

|

|

|

|

|

Lakshmi SK, Kumar SN (2011). Work-life balance of Women Employee-with Reference to Teaching Faculty. E-Proceedings for 2011 International Research Conference and Colloquium (pp. 22-58). Razak: University of Tun Abdul Razak, Malasyia.

|

|

|

|

|

Leovaridis C, Vatamanescu E (2015). Aspects Regarding Work-Life Balance of High-Skilled Employees in Some Romanian Services Sectors. Journal of Eastern Europe Research in Business and Economics pp. 36-51.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Maeran R, Pitareli F, Cangiano F (2013). Work-Life Balance and Job Satisfaction among Teachers. Interdisciplinary Journal of Family Studies 18(1):51-72.

|

|

|

|

|

Marmol AD (2019). Dimensions of Teachers' Work-life balance and School Commitment: Basis for Policy Review. IOER International Multidisciplinary Research Journal 1(1):110-120.

|

|

|

|

|

Meyer DJ, Turner J (2007). Scaffolding Emotions in Classrooms. International Journal of Social Sciences 19(12):243-258.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mohamed SA, Ali M (2016). The importance of Supervisor Support for Employees' Affective Commitment: An analysis of Job Satisfaction. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications 6(2):435-439.

|

|

|

|

|

Muasya G (2014). Is Work-Family Balance a Possibility? The case of Kenyan Female Teachers in Urban Public Schools. International Journal of Educational Administration and Policy Studies 31(8):37-47.

|

|

|

|

|

Muasya G (2016). Work-family Choices of Women Working in Kenyan Universities. SAGE 6(1):1-12.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Muhtar F (2012). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. Retrieved from Iowa State University:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Mukururi JN, Ngari JM (2014). Influence of Work-life balance Policies on Job Satisfaction in Kenya's Banking Sector; A Case Study of Commercial Banks in Nairobi Central Bussiness District. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (IOSR-JHSS) 14(7):102-112.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Murphy F, Doherty L (2011). The Experience of Work-life balance for Irish Senior Managers: Equality, Diversity and Inclusion. An International Journal 3(4):252-277.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Nwachukwu OP (2016). Teacher Education, School Effectiveness and Improvement : A Study of Academic and Professional Qualification on Teachers' Job Effectiveness in Nigerian Secondary Schools. Faculty of Behavioural Sciences at the University of Helsinki (pp. 1-259). Siltavuorenpenger: University of Helsinki.

|

|

|

|

|

OKoth UA (2008). Instructional Leadershipo Role of Head Teachers in the Implementation ofn Secondary School Environmental Education in Siaya District, Kenya. Nairobi, Kenya: Unpublished PhD Thesis, Catholic University of Eastern Africa.

|

|

|

|

|

Parasuraman S, Simmers C (2001). Type of Employment, Work-Family Conflict and Well-Being: A Comparative Study. Journal of Organizational Behaviour 22(25):551-558.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Perry RP, Menec VH, Struthers VW, Schonweter DJ (1997). Faculty In Transition: A Longitudinal Analysis of the Role of Perceived Control and Type of Institution in Adjustment to Postsecondary Institutions. Research in Higher Education 38(5):519-556.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Punia BK, Kholsa M (2009). Relational Analysis of Organisational Role Stress and Conflict Management Strategies in Indian Service Sector. IMS Manthan: The Journal of Innovations 4(3):37-50.

|

|

|

|

|

Ryan AM, Kossek EE (2008). Work-life policy implementatio: Braking down or creating barriers to inclusiveness. Human Resource Management Journal 47(2):295-310.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sang WH (2011). Factors Affecting Work-Life Balance Programs in State Corporations based in the Nairobi Region. Nairobi, Kenya: Unpublished PhD Thesis, Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology.

|

|

|

|

|

Shernoff E, Mehta T Atkins M, Torf R, Spencer J (2011). A Qualitative Study of the Sources and Impact of Stress among Urban Teachers. Journal of School Mental 3(2):59-69.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Singh S (2013). Work-Life Balance: A Literature Review. Global Journal of Commerce and Management Perspective 2(3):84-91.

View

|

|

|

|

|

Sirima NL, Poipoi MW (2010). Perceived Factors Influencing Public Secondary School Teachers' Job Satisfaction in Busia District, Kenya. International Research Journals 1(11):659-665.

|

|

|

|

|

Strathmore Research and Consultancy Centre. (2012). The Kenya Power Work-life balance: Results from the baseline survey. Canada: Work and Family Foundation.

|

|

|

|

|

Straub S, Hagiwara T (2011). Toulouse School of Economics. Retrieved from Asian Development Bank:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Subha T (2013). A Study on Work-life balance Among Women Faculties Working in Arts and Science Colleges with Special Reference to Coimbatore City. Parpex- Indian Journal of Research 2(12):160-163.

|

|

|

|

|

Tanvi MN, Fatima KZ (2012). Work-life balance: Is it a new Concept in Commercial BAnking Sector of Bangladesh. International Journal of Research Studies in Management 1(2):57-66.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Thornhill A, Saunders M (2008). What if Line Managers don"t Realize they're Responsible for HR? Personnel Review 27(6):460-476.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Uddin MR, Hoque N, Mamun AM, Uddin S (2013). Work-life balance: A Study on Female Teachers of Private Educational Institutions of Bangladesh. International Journal of African and Asian Studies 5(13):10-17.

|

|

|

|

|

Wachira E, Kalai JM, Tanui EK (2016). Relationship between Achievement-Oriented Leadrership Style and Teachers' Job Satisfaction in Nakuru County, Kenya. International Journal of Science and Research 5(2):1653-1657.

|

|