ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study was to identify and critically analyze the oralture products associated with rituals concerning twins among the Jopadhola of Uganda. The study had the following objectives: to establish the successive stages in the life of twins among the Jopadhola and the rituals which accompany them; establish the nature or categories and functions of the oralture produced around these rituals; and establish the content and the literary features of these oralture products. The study used a qualitative approach, involving observation and verbal interviews with twenty seven respondents. The researchers listened to songs in response to the designed interview schedule. The findings reveal that oralture around rituals concerning twins among the Jopadhola are rich in literary features like imagery, kenning, personification, metaphors, symbols, satire, hyperbole, repetition, similes and structure with numerous functions, categories and features that pertain to them. Songs proved to be more utilized than all other literary products and the least used are the sayings and folktales.

Key words: Oral literature, twin rituals, oralture products, literary features, Jopadhola, Uganda.

The Jopadhola are an ethnic group of Uganda who live in Tororo District in Eastern Uganda and comprise about two percent of the country's total population. They speak Dhopadhola (a Luo Language), which belongs to the Western Nilotic branch of the Nilo-Saharan language family (Ogot, 1967; Owor, 2012). The Jopadhola call their land Padhola which, according to historian Bethwell Ogot, is an elliptic form of “Par Adhola” meaning the “place of Adhola. Adhola was the founder father of the Jopadhola (Ogot, 1967; Oboth-Ofumbi, 1959).

The Jopadhola arrived in southeastern Uganda in the 16th century during the Luo migration from southern Sudan. They first settled in central Uganda, but gradually moved southwards and eastwards. Their kin who settled innorthern and central Uganda are Acholi and Alur populations, who speak languages similar to Dhopadhola. They settled in a forested area as a defence against attacks from Bantu neighbours who had already settled there. Unlike some other small Luo tribes, this self-imposed isolation helped them to maintain their language and culture amidst Bantu and Ateker communities (Ogot, 1967; Oboth-Ofumbi, 1959).

Those Luo who proceeded their migration eastwards into present day Kenya and Tanzania are the JoLuo (commonly referred to only as Luo). Legend has it that Owiny, the leader of the Kenyan Luo was the brother of Adhola the leader of the Jopadhola who decided to settle in Tororo instead of going along with his brother towards Kenya and Tanzania (Ogot, 1967; Oboth-Ofumbi, 1959).

Jopadhola speak a language which is related to those of Acholi, Lango, and Alur of Uganda and Dholuo language of Kenya. The Jopadhola call their language Dhopadhola. The prefix dho means "language of" and jo means "people of". The infix pa means possessive 'of' - hence Jopadhola means people of Adhola, and Dhopadhola the language of the Jopadhola (Ogot, 1967; Oboth-Ofumbi, 1959; Owor, 2012).

Among the indigenous Jopadhola, twins are believed to be a blessing to the family if they are properly handled with all the appropriate rituals, but if not, they can turn out to be a curse to the family and the clan as a whole. This is the reason why the rituals around the twins must be taken seriously by both the family and the society. Various rituals are carried out at different stages of development of twins: at birth, naming, puberty, marriage, and death which have rich oral literary features being the subject of this study.

Whereas considerable amounts of work on rituals have been documented among Ugandan Bantu and Luo, especially the Acholi and Lango, there is hardly any substantial study on the oralture and oral products generated around rituals concerning twins among this Jopadhola. This is the scholarly gap that this research seeks to fill.

Statement of problem

Among the indigenous Jopadhola, there are oralture products and rituals concerning twins that are associated with birth, naming, puberty, marriage, death, and planting and harvesting seasons which are hardly documented. The oral component of all these rituals made at different stages in the life of twins are very rich in literary content and expression; but no systematic study had yet been conducted into these oralture products with a view to determining their literary major. This study specifically focused on the utterances and performances generated at birth, naming, marriage and death among the Japadhola of Kisoko and Petta Sub-Counties in Tororo district, Uganda.

The purpose of the study is to identify and critically analyze the oralture products associated with the rituals concerning twins among the Jopadhola, with the specific objectives to:

1. To establish the successive stages in the life of twins among the Jopadhola and the rituals which accompany them.

2. To establish the nature, categories, functions of the oralture produced around these rituals.

3. To establish the content and the literary features of these oralture products.

Definitions and understandings of oral literature

According to the World Oral Literature project, Oral literature is a broad term which may include ritual texts, curative chants, epic poems, musical genres, folk tales, creation tales, songs, myths, spells, legends, proverbs, riddles, tongue-twisters, word games, recitations, life histories or historical narratives. Most simply, oral literature refers to any form of verbal art which is transmitted orally or delivered by word of mouth. Orature is a more recent and less widely used term which emphasises the oral character and nature of literary works (Finnegan, 2012).

In African Oral Literature for Schools, Jane Nandwa and Austin Bukenya (1983) define oral literature as "those utterances, whether spoken, recited or sung, whose composition and performance exhibit to an appreciable degree the artistic character of accurate observation, vivid imagination and ingenious expression" (Nandwa and Bukenya, 1983: 1).

The Canadian Encyclopedia suggests that "the term oral literature is sometimes used interchangeably with folklore, but it usually has a broader focus. The expression is self-contradictory: literature, strictly speaking, is that which is written down; but the term is used here to emphasize the imaginative creativity and conventional structures that mark oral discourse too. Oral literature shares with written literature the use of heightened language in various genres (narrative, lyric, epic, etc), but it is set apart by being actualized only in performance and by the fact that the performer can (and sometimes is obliged to) improvise so that oral text constitutes an event." (http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/literature-in-english/, accessed March 14, 2016).

The definitions earlier mentioned give very important characteristics of ‘oralture’ like spoken or recited utterances, and curative chant, which are very evident in oralture around twins in general and also among the Jopadhola.

Rituals around twin births among the Jopadhola

Birth rituals

When a traditional midwife finds out that a Japadhola pregnant woman is expecting twins, she does not tell her. This is because the revelation would make the expectant mother afraid as the indigenous Jopadhola fear the rituals concerning twins, and yet, if the rituals are not performed, bad luck would befall the family. At birth, the medicine man is given a white hen to sacrifice before cutting the twins' umbilical cords and administering medicine to both the twins and their parents.

After that, he or she bathes the twins in local herbs, which are mixed in water, as a sign of appeasing them. The medicine is administered to cleanse the family from bad omen. The parents of the twins and a nephew are kept in the house, away from the community for three or four days depending on the sex of the twins. The traditional drum, called buli, is sounded and accompanied with cultural songs to alert the community about the birth of twins. Special ululations (Kigalagasa) are also chanted to announce their arrival.

The placentas of the twins are buried at the entrance of the house of the parents and marked with a small stone. This ritual is done in the evening, after sunset. When a twin child dies, he/she is buried next to the spot where the placenta was buried. The father of the twins has to look for a special pot with two openings called Agulu rut. This kind of pot is also one of the artefacts that must be in a home where twins are born. This pot has many functions. If the family is going to plant millet, millet beer is put in this pot, and the twins sprinkle it in the garden before planting. When people want to brew millet beer, they must honour the twins first by performing this ritual of putting beer in this pot. In this way the beer will not get spoilt.

Naming rituals

When it comes to naming the twins, the parents are brought out of the house and made to sit directly at the door, then the medicine-man or woman sucks millet beer from the Agulu rut and spits on them. After, he or she puts a bangle on the hands of the twins while making some chants. The names of the twins are usually pre-determined, depending on the sex and order of birth; for example, if the first child to come out is a male, he is named Opio but if the child is a female, she is named Apio. The name given to the second child also depends on the sex of the child, for instance, Odongo is given to the male child and Adongo is given to the female. The parents also acquire special names. The father of the twins becomes Ba-wengi and the mother becomes Min-wengi. These names set them apart from ordinary parents. There are a lot of songs and oral literature around this ritual because the naming of the twins is supposed to be a happy moment.

At the naming ceremony, the nephew brings some special herb tendrils called Luwombele and ties them around the twins and their parents. He also ties the herbs on the hands of both the twins and the parents while saying, “Wengi me ruki mewini” Meaning; “Twins, we have brought your clothes, receive them with joy.” During this ritual, many people gather around the twins while rejoicing; they sing and dance around the compound, and make ululations (Kigalagasa).

Rituals at puberty

When twins reach puberty, they are allowed to share a small hut with their peers. This hut is called Odi nyir if it is for the girls and Odi chwo if it is for the boys. Normally, at this stage, the peers, particularly the girls, are regularly sent to visit their grandmother who trains them into womanhood. For example, they learn how to cook, talk, behave and dress up. They are also told stories like legends, myths, and folktales, as well as proverbs and sayings. When the girls gather to sleep every night, they discuss what their grandmother told them in turns and retell the stories. The girls are not supposed to receive sex education from their biological parents or guardians; this was taboo for the Jopadhola.

Marriage ritual

Among the indigenous Jopadhola, marriage was arranged and consented to by both parents of the bride and the groom. The intending spouses were not supposed to be clan mates as it was taboo. The twin girl had to be a virgin and should qualify in the entire test given to her. The groom’s parents would send delegations to the bride’s parents with valuable gifts in form of livestock, beads, ear-rings, necklaces, bracelets and bangles.

On the wedding day, the bride is escorted by her sisters, brothers, aunts, grandparents, a band of musicians and security operatives who are then welcomed excitedly, with singing and dancing by the groom’s family. The bride sits on the verandah of her mother-in-law’s house for the rituals of blessing and anointing with cow butter (moo dhiang). This makes her a married and wedded woman of that home and the clan. She is then given a goat before she takes a meal which is served in a wooden tray (wer) and earthen bowl (tawo). This bowl is kept away from her until another girl gets married in that home. The bowl (tawo) became the covenant of her lifetime in that home.

Burial rituals

If twins die, a number of rituals are performed by the medicine man or woman. The twins are not supposed to be mourned because this will invoke the spirits of the dead twins and the ancestral spirits to anger and it might result into the death of another member of the family at any moment. The twins are not buried like local people. Their bodies are, for example, tied with mutton from the lower stomach of sheep. The skin of the sheep is placed on the chest of the dead twin and a piece tied around the hands. The same is done to any of the parents of the twins when they die. Twins are buried late in the evening when the sun has gone down.

The need to develop local oralture around twin rituals among the Jopadhola

Although the study of African oralture has been available for a number of years, the development of oralture around twin rituals among the Jopadhola has not been given audience. However, the procedure made in universal oralture studies offers a broader framework that can be used to handle the topic of oralture around rituals concerning twins among the Jopadhola. Okpewho (1992), in African Oral Literature, emphasizes that:

The job of keeping our traditions alive seems also urgent enough for the subject of oral literature to be given full recognition as a prerequisite to an organization program of collection and documentation (Finnegan, 2012).

It is vital to note that this research is aiming at collection and documentation of the oralture around rituals concerning twins among the Jopadhola so that the generations to come will not lose out on their oralture. Mbiti (2003) recognises that:

Songs for ceremonial occasions have a great cultural significance. They are more of an expression of the deeply felt emotions of the community as a whole and not as individual. These songs are generally sung in groups. They are of great variety and there are different songs for different occasions.

All Africans sing in ceremonies, whether it is death, war, marriage, or other cultural activities. Songs are a very important aspect of the way Africans live. These songs are composed according to occasions and demand. Composing songs is easily done and accompanied by simple instruments. Art, attractiveness and creativity shape part of the African songs. Daeleman (1977) in “An Exploration of Multiple-Birth Naming Traditions in Sub-Saharan Africa” observes as follows:

African twins (or multiple-birth children, in general), according to their ethnic group and gender, are traditionally given specific names. Often, the siblings who proceeded and the ones who followed the twins are also given specific names. Traditional reactions to multiple baby births vary from culture to culture. However, a commonalty is the subjecting of those born in multiples to ritual cleansing. Some of this cleansing can involve wild partying. Generally, such births are regarded either as bad omens, or as mysterious extraordinary happenstances, or as symbols of goodwill from God or ancestors. The births, therefore, require proper ritual cleansing for their benefits to be realized or for their possible negative impacts to be counteracted or nullified. Improper handling of multiple-birth siblings would cause the spirits to vent their anger upon the family or the community. Multiples are indeed treated with extra care, if not suspicion.

Normally, the arrival of twins is greatly celebrated in different African cultures. Twins are treated as special people. The rituals around twins are very important to their lives right from birth till they die. In a way, twins are taken to be gods. The birth of twins is always a cause of joy and anxiety, a great deal of excitement as well as concern, more so if they happen to be identical twins. They are regarded as a special gift from the ancestors.

The rituals around twins give rise to one of the most distinguished oralture products in most parts in Uganda, particularly among the Jopadhola, but hardly any previously written work is available for reference. Furthermore, the birth of twins has a distinct meaning in Ugandan ethnic groups, including Jopadhola, as the twins are considered to bring along a message from the ancestors to their living descendants. Their birth is accompanied by specific rituals and a carefully patterned name-giving to people and cultures of Uganda. When writing about the Jopadhola, Nzita and Mbaga-Niwampa (1993) say the following:

The woman would give birth in her own hut. The traditional midwives or her mother-in-law would attend to the delivery…The woman would remain confined in the house for four days, if the child is female and three days if the child is male.

This is one of the rare documents concerning the rituals among the Jopadhola that have been written down but does not mention the attendant oral utterances on performances. Nzita and Mbaga-Niwampa (1993) further observe the following about marriage:

In marriage, traditionally, the parents of the boy would identify a girl for him and make arrangements for marriage. The formula governing such identification took into account the girl's conduct, that of her parents, the physical strength of the girl, her beauty and the ties of the kinship between the girl’s and the boys’ family.

Concerning death among the Jopadhola, Nzita and Mbaga-Niwampa (1993) emphasize that:

Whenever a person died, the corpse would stay overnight in the house. A long drum would be played at night and the corpse was bathed and wrapped in bark cloth. A cow was normally slaughtered near the grave in order to go with the deceased and feed him with milk in the world of the dead.

Whereas the above gives the rituals of marriage and death among the Jopadhola, they do not tackle the issues of oralture around rituals concerning the marriage and death of twins among the Jopadhola. When writing about the Acholi, Okumu (1994) states the following:

A family that produces twins is closed to the visitors and the husband separates with the wife for some time. The cord of each child was cut as in the case of other children and the placenta carried to some place near the house and buried where the sweepings from the hut might be thrown upon the spot. In the early morning, in the evening, and at intervals during the day, two small drums, one for each child, were beaten.

Okumu (1994) has made a great contribution to the study of Oralture around rituals concerning twins in the Acholi Luo; but he does not go further to discuss the Oralture around rituals concerning twins among the Jopadhola. “After three days,” Okumu (1994) continues to write:

The heads of the twins were shaved and their nails paired, and then for seven months the father collected fowls, goats and promises of food for the ceremony of bringing the twins out for inspection. The members of the two clans gathered and danced in two parties, escorts by songs and sayings, the father leading his relatives and the mother hers. They drank beer and blew it over the members of the other party as they danced, the idea, as in other tribes, being to divert from themselves any evil which might be attached to the twins and cast it on the other clan.

The Luo of Kenya also have special names for twins. The first-born twin is called Opio (meaning fast) if male and Apio (same meaning) if female. If one of the twins died, he or she had to be buried behind the mother's house. There was no mourning for a dead twin. The living twin was referred to as Abanji. A woman who gave birth to twins was forbidden from entering any house at her original (parental) home until her husband had given her parents a heifer and the door opening ceremony had been performed. (Wako, 1985). However, there is no mention of the accompanying literary utterances. When the twins are crawling a ceremony, in essence the same as that for bringing out the parents is performed to bring them out of the house. Copper or iron anklets are put on their feet, on the right foot for the first-born and on the left for the other.

This was a descriptive survey, based on a qualitative approach because of the anthropological nature of the study and the fact that oral literature is performed practically in a specific cultural context. The qualitative approach was used mainly because the overall data was verbal and visual. Data was collected through interviews and observation.

The study was done in Tororo District, about 220 kilometers east of Kampala, toward Kenya boarder. The particular areas of interest are two Sub-Counties of Petta and Kisoko. Kisoko is ten kilometers from Tororo town on Nagongera Road while Petta is almost twenty kilometers from Tororo town off Nagongera Road. These places were chosen because they are conveniently placed, thus, easy to reach. In addition, these people still value their rituals concerning twins.

The sample comprised of thirty respondents of different categories -medicine people, clan leaders, parents of twins and elders (Table 1). Sampling was purposively carried out to get respondents who have practical experience on the issues of literary interest with regard to twin ceremonies. These included twelve elders, two medicine men and two medicine women, ten parents of twins, and four clan leaders from Kisoko and Petta Sub-Counties. These comprised both men and women. These participants also belong to various clans and, therefore, the information obtained was considered to be representative.

The reliability and validity of the research instruments was ensured by use of simple and clear language. The researchers also ensured that the questions were formulated in a way that ensured consistency in responses. In order to ensure validity, the research instruments were validated through a pilot test of five respondents, who were interviewed on each item in the instruments, to ensure that the questions were clear and not ambiguous.

The data obtained in this research was recorded, edited, and refined on a daily basis, while the context of interaction was fresh in the researchers’ minds. The data was grouped according to the research questions. The qualitative approach was employed in the analysis of the data. This included critical analysis of oralture products around rituals concerning twins.

The oralture products associated with twin rituals

Table 2 shows that the actual as opposed to the planned respondents comprised of 18 mother of twins, 2 medicine women and 1 medicine man, 3 male clan leaders and 3 male elders. The categories of responds show some gendered division of labour where clan leaders and elders are a men preserve. The mothers on the other hand are more available, closer to children and have the rituals at their finger-tips.

All the respondents were married, and all of them had adequate knowledge of the oralture products associate with twin rituals. Among the Jopadhola, the lives of twins were not only of special socio-religious significance; they also gave rise to oral products of literary nature. These products include stylized utterances, pithy sayings, riddles, proverbs, songs, chants, and stories which are found at various stages of the life of a twin as presented below.

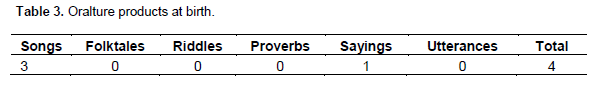

At birth

In connection with birth, out of 27 respondents three songs were gathered and one sayings; there were no forthcoming riddles, proverbs or folktales. The outcome is shown in Table 3. A female respondent, Alowo, said that as soon as the twins are born, a medicine-woman is sent for to sprinkle medicine on the twins and their parents. A nephew to the father of twins is also fetched to perform certain rituals. As the medicine-woman and the nephew arrive, there are ululations and songs such as Eeeh Awuyo, Awuyo pa ji (transl. Awuyo the owner of two) were sung to welcome the twins:

Song 1

Soloist Eeeh Awuyo, Awuyo pa ji aryo,

Awuyo Awuyo, Awuyo the owner of two

Chorus: Eeeh

Eeeh

Soloist: Eeeh Awuyo

Eeeh Awuyo

Chorus: Eeeh Sambara Awuyo

Eeeh Awuyo the owner of the two

Alowo further explained that the relatives of the mother of twins would perform the rituals while singing Eeeh chak chiewo (Eeeh fresh milk) whose function is to stress the importance of having children in a marriage. This song goes:

Song 2

Eeeh chak chiewo

Eeeh fresh milk

Nyoro aweyo thiang sira malo

Yesterday I left the udder heavy with milk

Ongoye ja nyiedho

There is no one to milk

Kononin akelo ri win wendo

Today I have brought for you visitors

The third song is skipped here because of space.

Saying 1

A woman in labour would be told the following saying as an encouragement to push the twins.

Saying: Dhoko nywol ri fwonji

A woman gives birth because of teaching.

Function: It is to encourage the woman to endure the pain of giving birth.

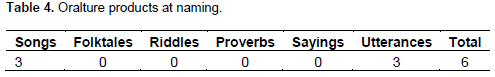

At naming

There were specific utterances and songs for the naming occasion. Table 4 shows the oralture products at naming that were found. Naming of twins and releasing them from house confinement was a big ceremony as it was a way of accepting the children into the clan. There were specific utterances and songs for the occasion. One of such utterance are given below:

Utterance 1

Paka wiyero bino I pecho me, wikiri wikeli teko, kwonyowoki bedi win gi kisagala gi kisi dhano.

Since you have decided to come to our home, be at peace with everybody.

The medicine-woman also sprinkled medicine on the twins saying:

Utterance 2

Wengi, chiemi wini maber.

Twins, eat well.

The above utterance was made to please the twins so that they would suckle well without refusing to do so.

Next, she would sprinkle medicine on the sheep that was going to be slaughtered so that the twins’ ash could be removed. She would say:

Utterance 3

Wengi me gimewin,

This sheep belongs to you.

Wakidho kwanyo woko buru me ka.

We are going to remove this ash from here.

Wikiri witimi wan marach

Let it be well with everyone in this home

Wikiri witimi marach joma kwanyo buru me.

Please do no harm to the people who are going to remove this ash.

In addition to special utterances, there were various songs sang during the naming of twins, but not given here in full because of space. In one of the songs the folks from the woman’s side would sing an obscene song in a jovial mood - Eeeee; Eeeee; Bedi ki nyaran manitye gi ng’onye ma luthi di wi kinwango wengi (If it was not our daughter with deep vagina, you wouldn’t have got twins). This utterance was to show pride in their daughter giving birth to twins. The side of the man would answer with a similar obscene song, accompanied by loud ululations of approval and merriment, which goes as follows: Eeeee; Eeeee; Wiwacho ango; Aka bedi ki wodi wan manigi there ma bori; di nyari win konwango rut; (What are you saying? If it was not for our son who has a long penis your daughter would not have given birth to twins). This song serves as a jocular counter attack by the man’s side against the proposition in the foregoing song by the woman’s party.

Shaving twins’ hair

Twins’ hair and that of their parents was shaved by a nephew with instructions from the medicine-person who would make utterances like: Wengi O’nyo walonyo win. Wikiri widhawi, bedi win gi kisagala (twins we are making you smart. Please do not quarrel, but be at peace with everyone).

Resumption of love-making

The parents of the twins were not supposed to make love before rituals were performed and certain utterances made otherwise the father of twins (Ba Wengi) would become impotent (lur). The father and mother of the twins would enter their bed naked and the medicine-woman would sprinkle medicine on them saying: “Ah, pama nyo ariwo win wibedi idel achiel. Paka wichowo kelo Wengi, keli wi doko man.” (Ah, now I join you to become one body. As you have brought the twins, bring many more).

During puberty

Table 5 shows the oralture products at puberty. The empirical study found eight songs, six riddles, three proverbs, two folktales and no sayings or utterances. The research found this stage to have the highest number of oralture products. One of the respondents, Nyapendi, said that puberty had to be treated with a lot of care using teachings, folktales, riddles, and proverbs among others, to prepare the twins for the life ahead of them. The twins did not sleep in their parents’ house but at their grandmother’s when at puberty. Their grandmother’s house would be called “girls’ nest” (odi nyiri). Here, they would learn a lot of things from their peers and grandmother. The girls in the same “girls’ nest” would do most of the things together like fetching water, collecting firewood, and grinding millet, among others.

Interviews with Nyaketcho (an informant), revealed that the girls at puberty sang many songs as they worked together to sustain concentration. One of the songs that the girls would sing while grinding was Mudole ma wan onyiew kune? (From where was our elephant grass bought?) Mudole onyiew Iganga; (our elephant grass was bought from Iganga). The song goes:

Song 3

Soloist: Mudole ma wan onyiew kune?

From where was our elephant grass bought?

Chorus: Mudole onyiew Iganga.

Our elephant grass was bought in Iganga.

Soloist: Mudole ma wan onyiew kune?

From where was our elephant grass bought?

Chorus: Mudole onyiew Iganga.

Our elephant grass was bought in Iganga.

Soloist: Kiidi pa adhadha rego ango?

What does grandmother’s grinding stone grind?

Chorus: Kiidi rego abwa.

The grinding stone grinds millet.

Soloist: Kiidi pa adhadha rego ango?

What does grandmother’s grinding stone grind?

Chorus: Kiidi rego abwa.

The grinding stone grinds millet.

This song encourages the girls to develop the habit of working hard at their domestic chores. One Nyadoi, who is seventy three years old respondent, revealed that among the Jopadhola, the girls would visit the bush with their grandmothers. Each of the girls would carry a rope for “pulling a goat.” ‘Goat’ would be used for politeness. This rope would help them to pull their labia minora and make it long. The girls’ grandmothers would also teach them a song that was associated with pulling the labia minora, which goes:

Song 4

Soloist: Ngori mit magira

White peas is sweet when the husks are removed

Chorus: Eeeeh nyagori

Eeeh white peas

Soloist: To ki mako oleriwa

And if you get roasted one

Chorus: Eeeh nyagori

Eeeh white peas

Soloist: To kodhi kafuta mere

And if you eat when it is grounded

Chorus: Eeeh nyagori

Eeeh white peas

Soloist: Ojang ojang

Let it to be very long

Chorus: Ojang de kiri piny

Very long up to down

Soloist: Onur onur

Let it to be very soft

Chorus: Onur de kiri pinyi

Very soft up to down

Function: It is encourage young girls to undertake this cultural practice because of its importance in sexual fulfillment.

Another respondent, Awino, revealed that if it happened that a twin getting married had not pulled her labia minora and her husband discovered after he had married her, he would go with his wife plus his brother to his wife’s grandmother to inform her. There was a song used to inform the grandmother that her granddaughter had not pulled her labia minora and the grandmother would teach her. The following song, sung by Nyabwolo to the researchers, would be sung for this purpose:

Song 5

Husband: Awiny odhieran

I’m defeated by this bird Awiny

Grandma: Nitye kune

Where is it

Husband: Nitye ka won

It is here with me

Husband: Awiny kimit furi

Awiny does not want to dig

Chorus: Eeeh nyagor

Eeeh white peas

Husband: Awiny ki chwoyi ng’ori

Awiny does not plant white peas

Chorus: Eeeh nyag’ori

Eeeh white peas

Husband: Awiny ki doyi ngori

Awiny does not weed white peas

Chorus: Eeeh nyagor

Eeeh white peas

Grandma: To ngori mit magira

But white peas is delicious without husks

Chorus: Eeeeh nyagori

Eeeh white peas

Grandma: To ki mako oleriwa

And if you eat the roasted one

Chorus: Eeeh nyagori

Eeeh white peas

Grandma: To kodhi kafuta mere

And if you test the grounded one

Chorus: Eeeh nyagori

Eeeh white peas

Grandma: Ojang ojang

Let it to be very long

Chorus: Ojang de kiri piny

Very long up to down

Grandma: Onur onur

Let it to be very soft

Chorus: Onur de kiri pinyi

Very soft up to down

Function: It is to shame those who feared pulling and to lay blame on the grandmother for ignoring her role.

Courtship

There were various songs sang during courtship. Agola, one of the women interviewed, revealed that it was at this stage that a twin girl was encouraged to befriend another girl from a neighbouring home or village, where her future husband would come from. Various songs, which include the following, were sung during the visits - Agwera jolan, agwera jolan agwera jolan atundi pecho (My friend receive me, my friend receive me at your home). This song stresses the importance of friendship, which dictates that a visiting friend should be received with all the joy. The full song goes as follows:

Song 6

Soloist: Agwera jolan, agwera jolan agwera jolan atundi pecho

My friend receive me, my friend receive me so that I can get home

Chorus: Agwera jolan, agwera jolan agwera jolan atundi pecho

My friend receive me, my friend receive so that I can get home

Soloist: Eeeh jolan, eeeh jolan eeeh jolan atundi pecho

Eeeh my friend welcome me eeeh that I may reach home

Chorus: Eeeh jolan, eeeh jolan eeeh jolan atundi pecho

Eeeh my friend welcome me eeeh that I may reach home

Soloist: Agwera jolan agwera jolan agwera jolan abende anujolin

My friend receive me so that I can do the same next time

Chorus: Agwera jolan agwera jolan agwera jolan abende anujolin

My friend receive me so that I can do the same next time

Agola, (respondent) also revealed that the hostess’s aunt would get a hen and welcome the visitor and her companions to the home with ululations while swinging the hen round the visitor’s head four times.

Riddles are also used when preparing girls and boys for marriage and future life. Examples include - Ango magoyo yokin to ineno? (What beats your mother as you watch?). The answer is: Koyi; (A gourd used for churning milk). This riddle teaches the girls hard work; the energetic churning of ghee out of milk by women being an instance of such hard work. Another riddle is -Muchugwa ochiek mito afwona (An orange is ripe and needs to be harvested). The answer is -Nyako othiki (A girl has attained the age of marriage and should go). This riddle was intended to encourage the girl child to get married. Marriage carried pride and dignity with it. She was more respected in her family and clan when she got married than when she was not.

Obbo and Nyeko also revealed that there are a number of proverbs used in the life of twins, especially during puberty, including - Dhiang m’ odong chien ama fwoyo luth (The cow that has remained behind is the one that gets all the beatings), intended to teach the youth to avoid being lazy at work. Also, Jambaka nyiewo mbiye (He who is stubborn buys raw bananas) is a proverb used to teach the girls to respect their husband’s decisions and not to be stubborn.

Marriage

According to Awor, (respondent) on the marriage day, the bride would be escorted by a band of musicians and security operatives. They would sing various songs, for example, - Mugole goyi ni ka ni ka ni ka (You bride walk with pride) and they would dance vigorously. The song encourages the bride to walk proudly to combat the impending challenges in marriage.

Aketch (respondent) revealed that the people escorting the bride to her new home would take two chickens because she was a twin and local millet brew in agulu rut (a pot with two openings) which would be used to sprinkle on her as a sign of good marriage and blessings. As the bride’s mother was sprinkling medicine on her daughter, she would ululate and say: Abino yiko nyaran’ (I have come to bless my daughter). The relatives of the bride would also sing: Janywoli k’onywolo nyathi ma nyako, wori kinindi, wori ka keko nindo kwano lwete. Chingan me, dhoki abich, Chingan me, diegi abich (Meaning when a parent gives birth to a girl, at night he/she doesn’t sleep. He/she sleeps while counting his/her fingers; this hand of mine is five cows; this other hand of mine five goats).

The song reminds the people of the benefits of producing girl children. The prospect of wealth the girl child portends can render the parents sleepless. At the end the bride’s mother would also say: Nyaran, amiyin silwany. Nyali nywolo nyithidho (My daughter, I am blessing you. May you give birth to many children).

Death

One medicine-woman, Osolo Eseza (respondent), revealed that when a twin dies, no one is supposed to say that the twin has died but that he/she has gone to visit. When the second twin dies, he/she is mourned. Dry banana leaves are cut and used for bedding and tying around the waist during the mourning period. In addition, a long drum is sounded. Mourners dance, sing and cry at the same time. One of the songs the mourners dance to is - Eeeeeeh eeeeeh okonjo iwan’gan lowo (O’ death has poured sand in my eyes). This song tells people how dreadful death is.

According to Nyafwono (respondent), one of the saying used during death is - Kikeli baliwa (Death does not inform us when it is coming). This saying warns people to be ready for death at any time. Also, one of the riddles used upon the death of twins is puzzle: Ongoye dhano jie ma nyalo nenan to aneno kisi dhano jie (I am not seen by anyone but I see everybody). This riddle shows how clever death is. It is always with us but we cannot see it.

Burial

Osolo and Oyuk (respondents) revealed that on the day the mourning period was to officially close, everybody would run to a nearby stream singing: Eeeh Awuyo, Awuyo pa jii ariyo (Awuyo, Awuyo the owner of the two). This emphasizes that saying goodbye to life should be done in the same spirit of celebration as in welcoming it into the world. Amita (respondent) also revealed that as a twin was buried, an utterance such as the following would be made: Paka wi wegi wimito kadho wendo, tundi win maber isiemi gi mar, weyi teko moroje okiri otimere ri nyawotini kodi wan (Since you decided to go away for a visit, please go in peace, love and bring no harm to your friend and us).

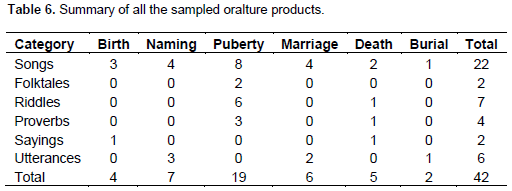

Table 6 summarizes the categories of the oralture products that were collected and analysed but not all have been discussed because of space. The research found many literary features in the oralture products generated around the rituals concerning twins among the Japadhola. In total, there were fourty-two oralture products. From birth to burial of twins, there were twenty-two songs, two folktales, seven riddles, four proverbs, two sayings and six utterances discovered. At birth there were four oralture products found; six at naming; nineteen at puberty; six at marriage; five at death and two oralture products were found in the burial rituals.

Various literary devices were identified in the songs figures of speech, such as, kenning and hyperbole; imagery in the form of metaphors, similes and personi-fication; symbolism; repetition; and poetic structure. Figurative language involves the use of “defamiliarised” words, language that creates interest by going beyond the obvious and plain, and so, in a Wordsworthian phrase, “throwing a strange colouring” over the words. Kenning is a device some authors use to denote something without naming it directly. In the Awuyo song, Awuyo stands for the clan of the mother of the twins; and “the owner of the two” stands for the mother of the twins.

In the song named Mudole, the girl has been named elephant grass, that grows with vigor and that one cannot get from nearby but from a place as far as Iganga. The jocular claims that twins are a result of a deep vagina and a long penis are obvious exaggeration. Exaggeration has been used to express the excitement of producing girl children, who are equated to five cows and five goats. There are many instances of imagery in the songs – which is the expression of one item or attribute in terms of another that is basically dissimilar – that were identified in the sampled songs. These images take the form of metaphors, similes, and personification.

In Song Okonjo iwangan lowo, (death has poured sand in my eyes) there is an image of death. The pain that death causes is expressed in the two visual images of pouring sand into the eyes, and that of taking sleep from the eyes. Empirical research also identified personification in the expression ‘does not write a letter’. Death has been given the attribute of a human character of writing a letter to someone.

It was found that the twins, their names, the ritual knife, and the pot were all symbolic. Twins, in essence, were symbolic. They could be a curse or a blessing. If the necessary rituals were not performed properly, the curse could come; and if the rituals were performed well, the result would be blessings. Also, a special knife that was used for informing the twins’ relatives was symbolic of the birth of twins. The names Opio/Apio and Odongo/Adongo are ancestral names that symbolise the manifestation of the past within the present. Furthermore, the pot with two openings symbolises a womb that carries two children.

Satire, the employment of humour to criticize someone or something by way of ridiculing or belittling them, was also revealed in the research. The research identified satire in song Agwera ka woni ka (my friend this is home) mafwodi ikibedo ilokere woni pecho (before sitting you turn to be the owner of the home). When guests failed to behave in an appropriate manner, the host sung for them this song to wittily ridicule them. They were supposed to behave like visitors and not like owners of the home. Repetition, which is a key feature of the songs, is often employed for emphasis or for rhythmic purposes.

Five images were pointed out in this research. All these images have been got from the songs. They all help to upload the meanings of these songs. They are also used for euphemistic purposes. Without the images, the songs would be embarrassing when sung in the midst of both the old and the young. Therefore songs use common images to reveal hidden meaning for teaching purposes to the growing twins.

The literary features of the oralture products identified and pointed out here are: repetition that has been found in all songs and in the folktales. Indeed the repetition enabled the emphasis to stand out clearly in these songs and in the folktales. Also kenning with a total of seven instances of kenning realised and they are mostly found in the songs. This brings out idea of the musicians being so keen in creating new words combinations when composing the songs. It also shows that these songs used here are not plain but they are all clothed heavily with a lot of meaning. Others include hyperbole, identified twice in the research and used purposely to exaggerate the power of death over life. This also indicates that no man can stop death from taking away a life at any time of day and at whatever age of an individual. Furthermore are similes. Two similes were noted in folktales re-told during puberty; and at no other stages have similes been identified. This indicates that it was only during puberty that almost all the literary devices are used. It is also right to say that puberty is a very fertile stage in the life of twins among the Jopadhola culture.

Other literary features include symbolism where ten symbols were identified, most of them in songs. This reveals that songs are the major devices and so they have the most symbols. In addition are metaphors where a total of four metaphors were identified, specifically in the songs. The purpose is to load the words in the song with a lot of meaning so that the ordinary man or child may not easily use it in a wrong forum.

Since the Jopadholas are mainly peasants, all the literary devices employed are based on things that surround them like certain type of vegetables, grasses, bananas, seeds, flowers, fruits, sand, birds, insects, animals, milk, and granaries.

Various oralture products were identified and these include songs, folktales, riddles, proverbs, sayings and utterances. All the oralture products are made use of objects and other items that the twins are farmiliar with to make them understand better. These were to mainly educate the twins so that they are well prepared for the future life that awaited them.

Various literary features were identified in the oralture products surrounding the twins. These include symbols, imagery, kenning, personification, hyperbole, similes, satire, humour, repetitions, metaphor and idioms. All these literary devices are used to convey messages loaded with a lot of meaning and to make the twins ready to live to the moral code of the community that they have to emulate later on.

The Jopadhola should continue with the practice of rituals concerning the twins because they are rich in oralture and valves which are helpful to both the life of twins, youth and their families at large. The original rituals concerning twins should be electronically recorded in more than one mode: audio, video and films. Through these, the orality and perfor-mance will be preserved. This would save the originality of the musicality, oralture, pitch and the intonation in the original art of the oralture around rituals concerning twins among the Jopadhola. The Jopadhola community should embrace these values as they are rich in information for insight into the way of life in society. The Jopadhola youth should learn and take to heart what is taught in the rituals as they are useful for puberty and maturity as respectable member of the community.

The Jopadhola writers should document how the Jopadhola lived and publish them. Literature concerning different clans among the Jopadhola should be written in form of poems and stories so that it can be accessible and read. This will also help in preserving original rituals and literature.

SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH

Further research should attempt to increase the sample and cover all the seven sub-counties in the district but also compare oral products on rituals associated with simple and multiple births. Attempts should also be made to track the changes that have occurred in the twin rituals among the indigenous and the current Jopadhola but among the urban and the rural Jopadhola.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Finnegan R (2012). Oral literature in Africa. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Mbiti JS (2003). Introduction to African Religions. 2nd ed. Nairobi: East African Educational Publishers.

|

|

|

|

Nandwa J, Bukenya A (1983). .African Oral Literature for Schools: Nairobi Longman.

|

|

|

|

Nzita R, Mbaga-Niwampa (1993). Peoples and Cultures of Uganda: Kampala: Fountain Publishers.

|

|

|

|

Oboth-Ofumbi ACK (1959). Padhola, Nairobi: East African Literature Bureau.

|

|

|

|

Ogot B (1967). History of the Southern Luo: Volume 1: Migration and Settlement 1500–1900. East African Publishing House. P 85.

|

|

|

|

Okpewho I (1992). African Oral Literature: Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

|

|

|

|

Okumba M (2003) Studying Oral literature: Nairobi: Acacia Publisher.

|

|

|

|

Okumu C (1994). "Acholi Orality". Uganda: The Cultural Landscape: Ed. Eckhard Breitinger Kampala: Foundation Publishers.

|

|

|

|

Owor M (2012). "Creating an Independent Traditional Court: A Study of Jopadhola Clan Courts in Uganda" J. Afr. Law. 56(2):215-242.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Wako DM (1985). The Western Abaluyia and Their Proverbs: Nairobi: Kenya Literature Bureau.

|