ABSTRACT

This study assessed the benefits derived by fish farmers from Fadama II project in Lagos State by interviewing 185 fish farmers who participated in Fadama II project from 9 Fadama Community Associations (FCAs) through a multistage sampling technique. Data collected with the aid of structured interview guide were analyzed with descriptive statistics and Chi-square. Majority of the fish farmers were male (71.89%), Christians (53.51%), married (41.62%) and educated (89.19%). The mean level of participation indicated that fish farmers participated mostly in decision making (2.97), election of group/association executives (2.95) and attendance at group meetings (2.86). The fish farmers benefited mainly from technical support through training, technological and material supports via the project. The fish farmers greatly benefited from the provision of fingerlings (96.77%), provision of drag net (96.77%), provision of generator (94.05%), purchase of weighing machine (92.97%) and provision of pelleting machine (92.43%). Acceptance of production system for use was high for concrete tanks (69.73%), earthen pond (58.92%) and wooden tank system (50.27%). The result of Chi-square deduced that there were significant associations between the fish farmers’ level of benefit derived from Fadama II project and their level of participation in decision making (χ2=7.153, p<0.05), financial contribution (χ2=6.122, p<0.05), advisory services to other group members (χ2=10.903, p<0.01), maintenance of association equipments (χ2=10.121, p<0.01), rehabilitation or construction of local fish markets (χ2=0.003, p<0.01) and election of association executives (χ2=11.415, p<0.01). The study therefore concluded that NFDP II has not only economic benefits but also social, technological, technical and material supports on fish farming in Lagos State and recommended that development projects should employ the demand-driven, bottom-top, informal and community-driven approaches in addressing the need of the poor in rural areas.

Key words: Training, social benefits, group participation, fisheries, National Fadama Development Project (NFDP II).

Agriculture remains the most important sector of the Nigeria’s economy despite the nation’s reliance on crude oil and its products since the commercial exploration of oil in the early 1970s and the consequent neglect of the

agricultural sector. The continued importance of the sector is because, it accounts for about 42% of the nation’s total Gross Domestic Product-GDP (Olomola, 2013) and employing 65 to 70% of the nation’s working population (Olomola, 2013; Emeka, 2007 cited by Olajide et al., n.d.; Sekumade, 2009 cited in PRESHSTORE, 2013).

The neglect of the agricultural sector by the government coupled with the teeming population of Nigeria led to decrease in the exportation of important cash crops like cocoa, palm-oil, groundnut, etc and even decreased production of staple food. This made the country to expend billions of Naira on importation of food crops like rice, wheat, sugar and even fish (Nwajiuba, 2013). Fisheries are one of the four important subsectors of Nigeria’s agriculture. Fisheries contribute about 4% agriculture’s share of the GDP (National Technical Working Group- NTWG, 2009). While the crop and livestock production subsectors had been stable over the years in terms of their contributions to the nation’s GDP, the contribution of fisheries has been on the increase with forestry’s share declining. According to Adekoya and Miller (2004) cited by Kudi et al. (2008), fish and its products contribute more than 60% of the total protein intake of adults, especially in rural areas.

Despite the favourable natural endowments that the country has been blessed with in terms of the coastal shelf area and the vast networks of inland waters like rivers, flood plains, lakes and reservoirs, local fish production has failed to meet the nation’s domestic demand (FAO, 1995 in Kudi et al., 2008; Federal Department of Fisheries- FDF, 2007 cited in NTWG, 2009). This led to the importation of about 700,000 tonnes of fish per year (FDF, 2007). No wonder, Nigeria has been regarded as the biggest importer of fish in Africa when the present per capita fish consumption level in the country is considered (Olaoye et al., 2014).

To arrest this ugly situation, successive Nigerian governments initiated and implemented series of agricultural development policies, strategies and programmes with very few making significant impact while most had little or no effect in the lives of the people. Such programmes were aimed at increasing local food production, increasing income of farmers, improving the living condition of the poor, women and other vulnerable groups among other good intentions of the government in order to ultimately reduce poverty which is one of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). One of the poverty reduction programme of the Nigerian government is the National Fadama Development Programme (NFDP). The programme is being implemented in phases known as projects.

The first phase of the National Fadama Development Programme, known as Fadama I was implemented between 1993 and 1999 through the top-down and supply-driven approach. It focused on crop production leaving out other subsectors of agriculture by providing crop farmers with boreholes and pumps through simple credit arrangements. Following the shortcomings of Fadama I, the second phase, branded as Fadama II was Fadama I, the second phase, branded as Fadama II was launched in 2004 and first implemented in 2005. Fadama II employed the bottom-top approach, community-driven and participatory development approaches and included other Fadama resource users like fisher-folks, hunters, vegetable farmers, etc with the primary aim of empowering the local communities in order to improve governments’ capacity to reach out to poor people in Fadama areas (FDF, 2008). This was achieved by designing and implementing production plans through the respective Fadama User Groups (FUGs) in the different Fadama Community Associations (FCAs).

Benefits derivable from any empowerment projects, especially those that incorporated the essential components of community-driven development (like Fadama II) could be financial (increased income or decreased production cost), social (human relations within groups), technological (use of improved technologies) and technical (acquisition of technical skills through training). It has been noticed that most researches that assessed Fadama II project had concentrated on the economic benefits through increased production output, increased income and decreased production cost while neglecting other categories of benefits. It is against this background that this study assessed these other benefits (technological, technical and social benefits) that the participants (fish farmers) derived from the implementation of the project in Lagos State, Nigeria. These benefits are expected to sustain the interest of fish farmers in fish farming even at the expiration of the project.

Fishing is the most important occupation of the rural population along the coastline and river courses, ranking next to crop farming in terms of occupation of all rural households in the state. Artisanal fishing is prominent along the coastal areas of the State covering Ibeju-Lekki, Lagos Island, Epe, Ikorodu and Badagry. The state has an extensive network of Lagoon Rivers, creeks, swamps and estuaries which makes up 22% of its total land mass and this gives the state a comparative advantage over other states of the Federation in fishing and related activities (Olaoye, 2010; National Bureau of Statistics- NBS, 2007).

This study was carried out in Lagos State. Lagos State is the second most populated country in Nigeria (National Population Commission- NPC, 2006). It is a state located in the southwestern part of the country with 20 local government areas (LGAs). ). Lagos is a marine state in the Federal Republic of Nigeria and has a land area of 3,577 km2 representing 0.4% of the total land mass of Nigeria, making it the smallest state in Nigeria in terms of its land mass (but it is arguably the most economically important state in Nigeria). It is bordered in the South by the Atlantic Ocean, in the West by the Republic of Benin, in the East and North by Ogun State and stretches over 180 km along the coast of the Atlantic Ocean (Lagos State Agricultural Development Agency- LASADA, 2002). Fishing is the most important occupation of the rural population along the coastline and river courses, ranking next to crop farming in terms of occupation of all rural households in the state. Artisanal fishing is prominent along the coastal areas of the State covering Ibeju-Lekki, Lagos Island, Epe, Ikorodu and Badagry. The state has an extensive network of Lagoon Rivers, creeks, swamps and estuaries which makes up 22% of its total land mass and this gives the state a comparative advantage over other states of the Federation in fishing and related activities (Olaoye, 2010; National Bureau of Statistics- NBS, 2007).

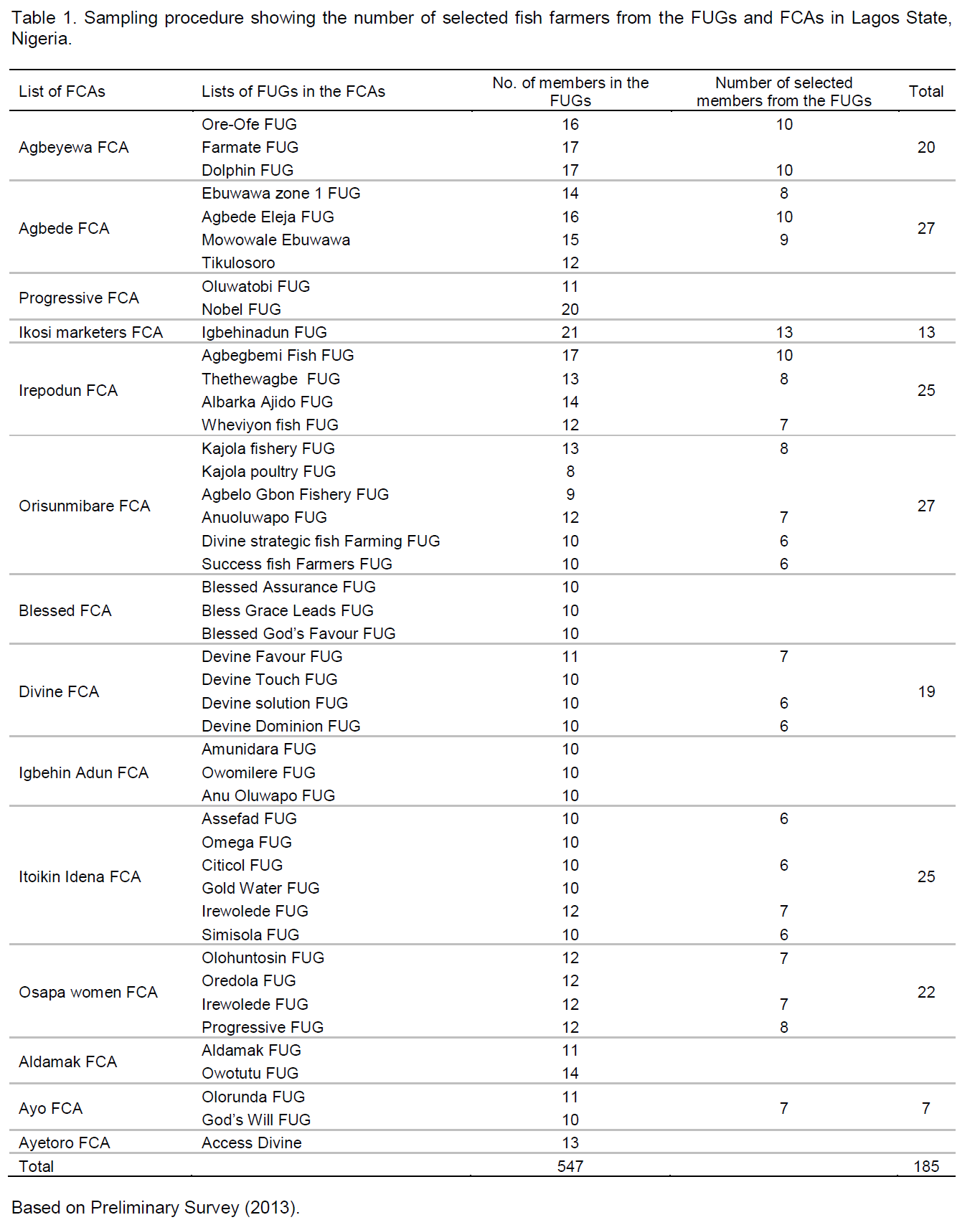

Out of the 10 local government areas (LGAs) of Lagos State that participated in Fadama II project, 7 had fish farmers in their Fadama Community Associations. One hundred and eighty-five fish farmers were sampled through the multistage sampling technique as described below and presented in Table 1.

Stage 1 involves the random selection of 9 out of 14 Fadama Community Associations of fish farmers from the 7 LGAs. This constitutes two-thirds of the FCAs. This was followed by the random selection of two-thirds of the Fadama Users groups (FUGs) which resulted in the selection of 24 out of the 34 FUGs in the 9 FCAs. The final stage involves the random sampling of 60% of the members in each of the selected FUGs and this resulted in 185 fish farmers.

Information was elicited on the socioeconomic characteristics, level of participation in Fadama groups’ activities, kinds of benefits derived from Fadama II project and the level of benefit derived from the project from the 185 sampled participants of Fadama II projects who were fish farmers. Collected data were analyzed with both descriptive (frequency, percentage and mean) and inferential (Chi-square) statistics. Results were presented in distribution tables.

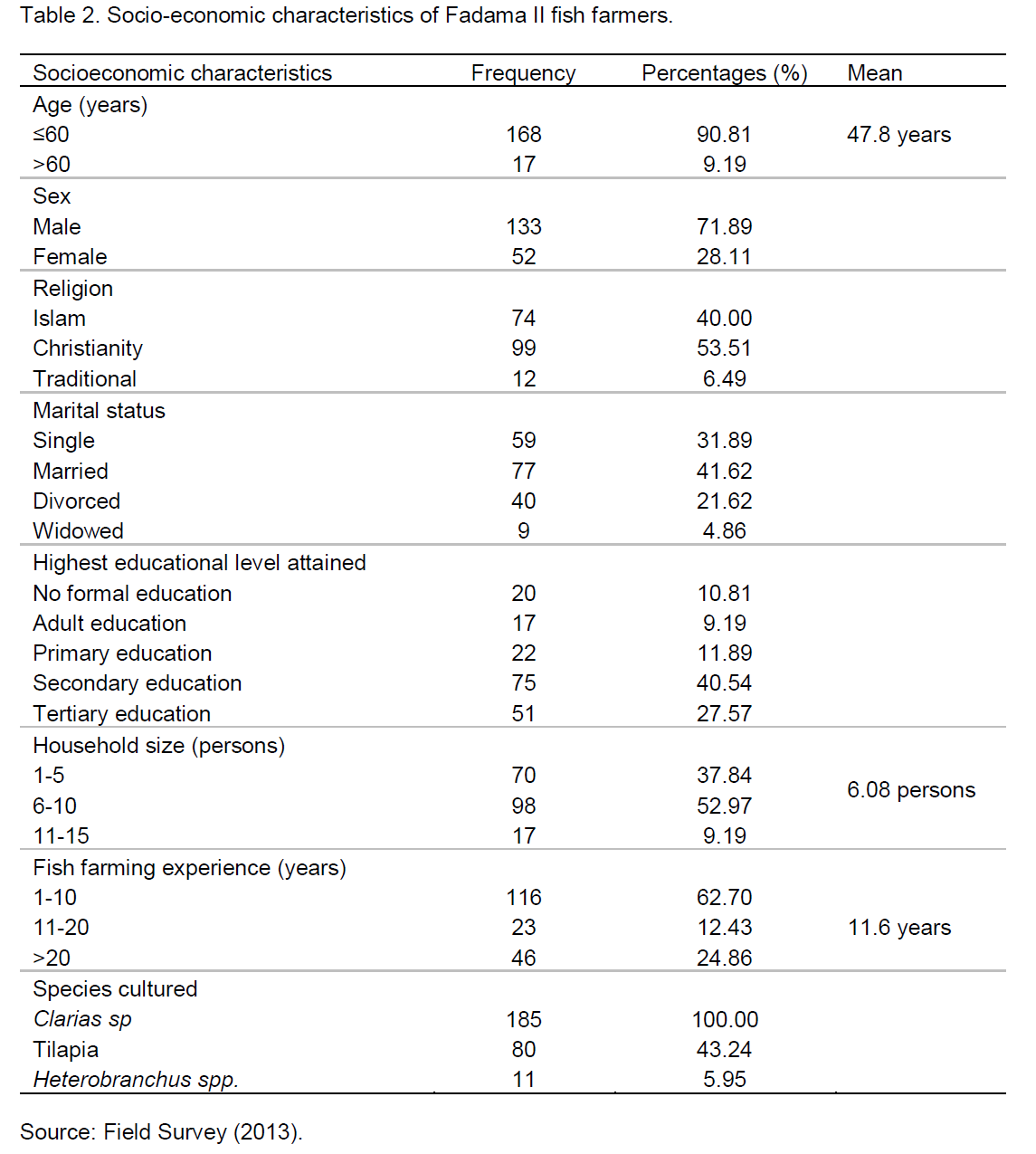

Socioeconomic characteristics of Fadama II fish farmers

In Table 2, about 90.81% of the Fadama II fish farmers were 60 years or less. This implies that higher proportion of the fish farmers who participated in the Fadama II project were in the working population. Majority of the fish farmers were male (71.89%), Christians (53.51%), married (41.62%) and educated (89.19%). Table 2 further reveals that the highest proportion (40.54%) of the fish farmers had at least secondary education while about 27.57% of them had at least tertiary education. This shows that the fish farmers who participated in Fadama II project in Lagos State were not illiterates. These findings were in line with the reports of Oladoja and Adeokun (2009) and Henri-Ukoha et al. (2011) which found that most Fadama fish farmers were still active, vibrant and dynamic; married and practiced Christianity, male-dominated and moderately educated. Similar findings about the socio-economic characteristics were observed among the Fadama II fish farmers in Ogun State (Olaoye et al., 2011).

Result from Table 2 further reveals that majority (52.97%) of the fish farmers had household sizes of 6 to 10 persons with a mean household size of approximately 6 persons. A mean fish farming experience of 11.6 years was found among the Fadama II fish farmers with the majority (62.70%) of the fish farmers having between 1 and 10 years of fish farming experience. The participants were culturing Clarias sp; tilapia and Heterobranchus sp. Table 2 shows that all (100%) of the fish farmers cultured Clarias sp in combination with either tilapia or Heterobranchus sp. with only 5.95% combining the three species. This agrees with the findings of Olaoye et al. (2011) that many of the fish farmers cultured Clarias sp. more than any other fish species. The reasons attributed to this are that Clarias sp. have higher market value, is more tolerant, hardy and attain market size in a shorter time (Olaoye et al., 2007).

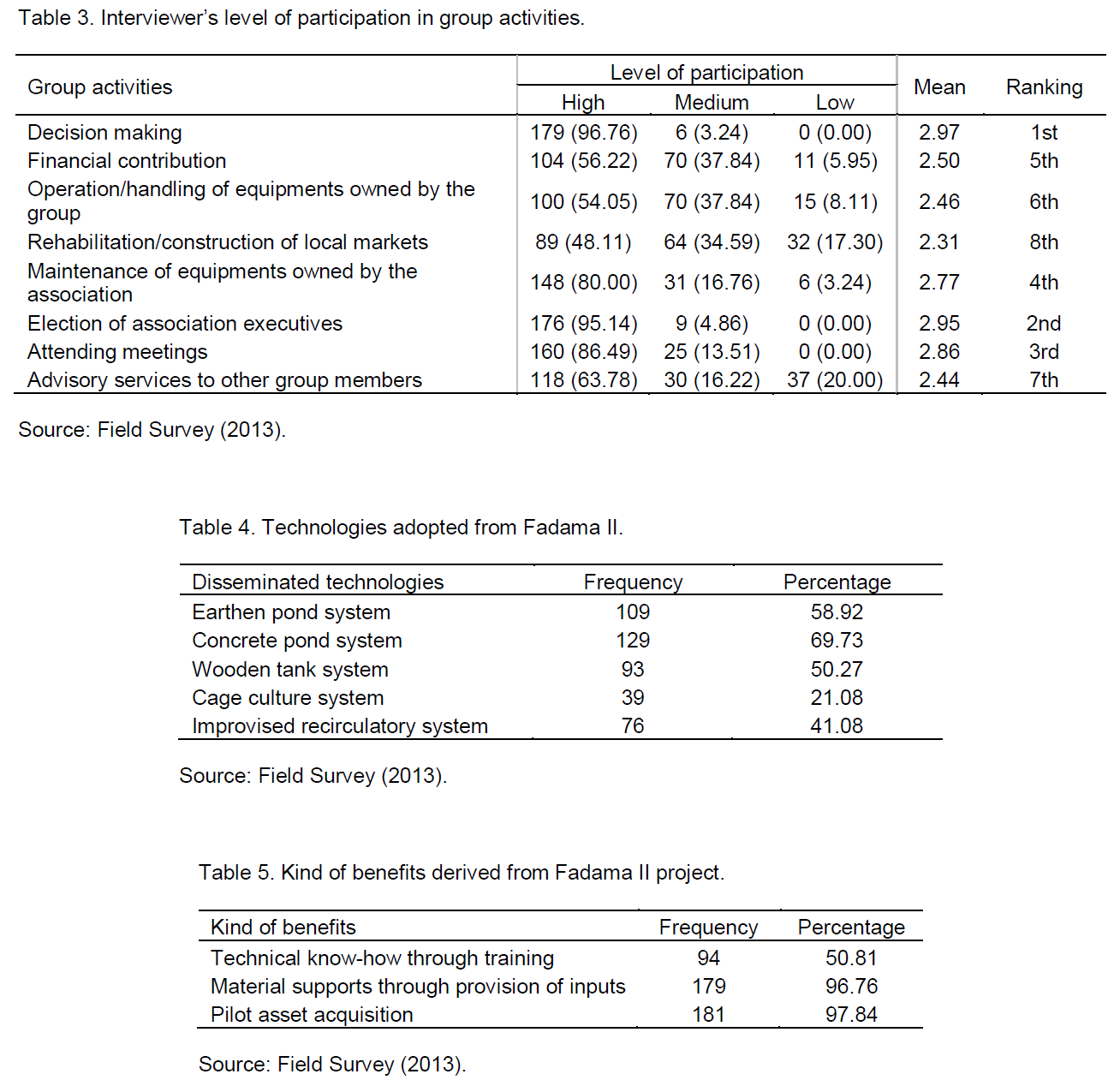

Level of participation in group activities

Table 3 reveals that all the group activities identified in this study received high level of participation from fish farmers. However, their degree of participation varied. The mean level of participation in Table 3 further ranked fish farmers’ participation in decision making (2.97) first, followed by their participation in election of group/association executives (2.95), attendance in group meetings (2.86), maintenance of association materials and equipments (2.77), financial contribution to the growth and development of Fadama User Groups (2.50), handling of association equipments (2.46), advisory services to other group members (2.44) and rehabilitation/construction of local markets (2.31). The high level of participation of the fish farmers in their respective FUGs and FCAs is expected to strengthen both the associations and group members socially, economically and financially. This is in consonance with the views of Ladele (1995) cited by Oladele and Afolayan (2005) that included self improvement due to skill acquisition and provision of supportive services to compliment education function of extension as some of the advantages of using farmers’ associations.

Technologies adopted by fish farmers from the Fadama II project

Improved technologies like earthen pond, concrete pond, wooden tank, cage culture and improvised recirculatory systems were introduced and disseminated to the fish farmers within the six years of implementing the Fadama II project. Table 4 shows the varied degree of acceptability the different technologies received by the fish farmers. While earthen pond and concrete pond production systems were accepted for use by 58.92% and 69.73% of the fish farmers respectively, just about half (50.27%) accepted the use of wooden tank system. Also, the cage culture and improvised recirculatory systems were only accepted by 21.08 and 41.08% respectively. The variation observed in the adoption of the different technologies by the fish farmers proves the fact that innovations are not usually adopted by all farmers at the same rate.

This made Adekoya and Tologbonse (2005) to categorize adopters into the innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority and the laggards/late adopters. The variation in the rate at which the fish farmers adopted the different technologies is also attributed to the compatibility, relative advantage and complexity of the different technologies to their existing production systems.

Kind of benefits derived from Fadama II project

The fish farmers’ benefits were categorized as technical, material supports and pilot asset acquisition in this study. Table 5 reveals that almost all the fish farmers benefited from material supports through the provision of inputs (96.76%) and pilot asset acquisition (97.84%) while just about half of the fish farmers benefited from technical know-how through trainings received on fish preservation and hatching of fingerlings. This supports the findings of Olaoye et al. (2011) which reported that majority of the fish farmers had one form of training or the other on fish production. Olaoye et al. (2011) also reported that Fadama II project supported fish farmers with inputs while also providing them with pilot asset acquisition support. All the broad categories will ultimately contribute to the social and economic benefits of the farmers.

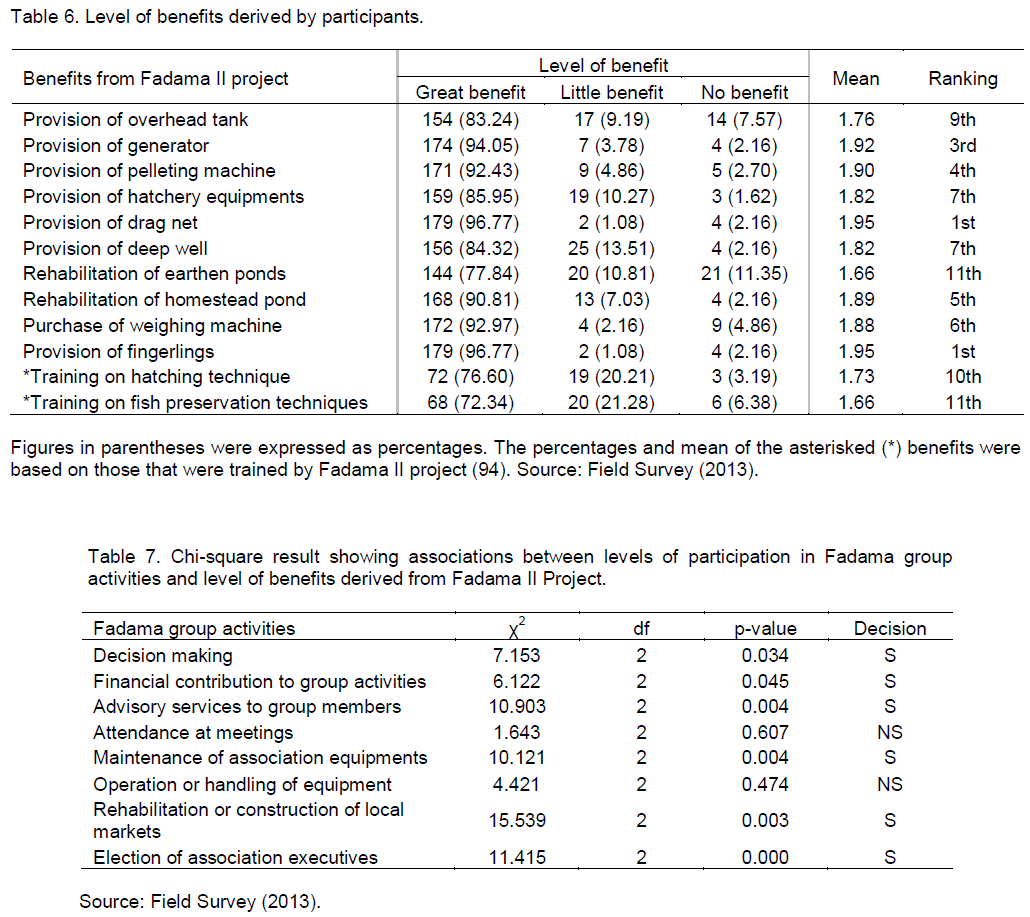

Level of benefits derived by fish farmers

Table 6 reveals that majority of the fish farmers greatly benefited from the provision of overhead tank (83.24%), provision of generator (94.05%), provision of pelleting machine (92.43%), provision of hatchery equipments (85.95%), provision of drag net (96.77%), provision of deep well (84.32%), rehabilitation of earthen ponds (77.84%), rehabilitation of homestead pond (90.81%), purchase of weighing machine (92.97%), provision of fingerlings (96.77%), training on hatching technique (76.60%) and training on fish preservation techniques (72.34%). The mean level of benefit derived from Fadama II indicated that the fish farmers benefited most from provision of drag net and provision of fingerlings while the least benefits were derived from rehabilitation of earthen pond and training on fish preservation techniques. With the great benefits derived by the fish farmers from Fadama II project, there is an assurance that fish farming in Lagos State could be sustained and hence, there is high potential that local fish production in Lagos State can be increased in the shortest period of time.

Association between fish farmers’ level of participation in Fadama group activities and the level of benefits derived from the project

Table 7 shows that there were significant associations between the fish farmers’ level of benefit derived from Fadama II project and their level of participation in decision making (χ2=7.153, p<0.05), financial contribution (χ2=6.122, p<0.05), advisory services to group members (χ2=10.903, p<0.01), maintenance of association equipments (χ2=10.121, p<0.01), rehabilitation or construction of local fish markets (χ2=0.003, p<0.01) and election of association executives (χ2=11.415, p<0.01). This implies that fish farmers who highly participated in these group activities benefited more greatly from the Fadama II project than those who participated at a lower level. This is because those who participated highly in these group activities are more recognized by group representatives; and hence may be better informed about the project than members who participated at lower level. Also, level of participation in terms of meeting attendance and handling of equipments do not affect farmers’ benefit level.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Increased income and other economic benefits may not be separated from projects that focused on poverty reduction. This study revealed that social benefits are also possible in most projects like Fadama II. It concludes that a fish farmer benefited from the Fadama II project according to his/her extent of participation in Fadama group activities. Benefits derived from Fadama II project, according to the result of this study were technical, technological and material supports. Great benefits were derived from all material and technical supports. It is therefore concluded that social benefits are essential in ensuring the sustainability of a project directed at the poor, rural dwellers with the aim of reducing poverty. This study recommends that the organizers, coordinators as well as planners of poverty reduction and rural development projects should adopt the use of community-driven development, bottom-top and demand-driven approaches that centered on the beneficiaries in the implementation of such important projects. Also, project assessment agents or organizations should not leave out social benefits from the indicators of success of a project.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Adekoya AE, Tologbonse EB (2005). Adoption and Diffusion of Innovations. In: S. F. Adedoyin (Ed.). Agricultural Extension in Nigeria, pp. 28-37. |

|

|

|

Adekoya BB, Miller JW (2004). Fish cage culture potential in Nigeria-An overview. National Cultures. Agric. Focus 1(5):10. |

|

|

|

Federal Department of Fisheries- FDF. (2008). Fisheries Statistics of Nigeria, Fourth Edition, 1995-2007, Nigeria. p 48. |

|

|

|

Henri-Ukoha A, Ohajianya DO, Nwosu F O, Onyeagocha SUO, Nwankwo UE (2011). Effect of World Bank Assisted Fadama II Project on the Performance of Fish Farming in IMO State, South East Nigeria: A Comparative Evaluation. Am. J. Exp. Agric. 1(4):450-457. |

|

|

|

Kudi TM, Bako FP, Atala TK (2008). Economics of fish production in Kaduna state, Nigeria. ARPN J. Agric. Biol. Sci. 3 (5&6):17-21. |

|

|

|

Lagos State Agricultural Development Agency- LASADA. (2002). Mid-Year Review of Agricultural Activities in Lagos State, ADP. P. 80. |

|

|

|

National Bureau of Statistics- NBS. (2007). Nigeria Poverty Assessment (harmonized). National Bureau of Statistics, Abuja. |

|

|

|

National Population Commission- NPC (2006). Human Population Figures of Census in Nigeria. |

|

|

|

National Technical Working Group- NTWG. (2009). A 2009 report of the Vision 2020 of the National Technical Working Group on Agriculture and Food Security. |

|

|

|

Nwajiuba, C (2012). Nigeria's agriculture and food security challenges.Available on www. boell. org/downloads/4_Green_Deal_Nigeria_AGRICULTURE. pdf. |

|

|

|

Oladele W, Afolayan SO (2005). Group dynamics and leadership in Agricultural Extension. In: S. F. Adedoyin (Ed.). Agricultural Extension in Nigeria, pp. 134-138. |

|

|

|

Oladoja MA, Adeokun OA (2009). An appraisal of National Fadama Development Project (NFDP) in Ogun State, Nigeria. |

|

|

|

Olajide OT, Akinlabi BH, Tijani AA (n.d.). Agriculture resource and economic growth in Nigeria. Eur. Sci. J. 8(22):103-115. |

|

|

|

Olaoye OJ (2010). Dynamics of the adoption Process of Improved Fisheries Technologies in Lagos and Ogun State. An unpublished Ph.D thesis, Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta, Ogun State. p. 2. |

|

|

|

Olaoye OJ, Adekoye BB, Ezeri GNO, Omoyinmi GAK, Ayansanwo TO (2007). Fish hatchery production trends in Ogun State: 2001-2006. J. Field Aquat. Stud.-Aquafield 3:29-40 |

|

|

|

Olaoye OJ, Oyekunle O, Omoyinmi GA K, Akintayo IA, Arogundade BF (2011). Contributions of the Fadama II project to aquaculture development in Ogun State, Nigeria. J. Humanit. Social Sci. Creative Arts 6(1):11-24. |

|

|

|

Olaoye OJ, Oyekunle O, Akintayo IA, Ahhibi G, Abdulraheem I (2014). Farmers' use of improved acquaculture management practices in Western zone of Lagos State Agricultural Development Programme (ADP), Nigeria. Nig. J. Anim. Prod. 41(1): 244-257. |

|

|

|

Olomola AS (2013). The political economy of food price policy in Nigeria. World Institute for Development Economics Research, WIDER Working Paper No. 2013/016. |

|

|

|

PRESHSTORE (2013). The impact of agricultural development on Nigerian economic growth. Powered by Preshnet. |