ABSTRACT

Acquiring cultural competence is an ongoing process in which healthcare professionals strive continuously to achieve the ability to work effectively within the context of their client’s culture. This study investigated clinical cultural competence of Saudi student nurses’ behaviors at the University of Hail, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The Cultural Competence Clinical Evaluation Tool- Teacher Version was used to measure the different dimensions of Saudi student nurses’ clinical cultural competence behaviors as rated by their clinical instructors. The student nurses level of clinical cultural competence behavior was rated as “average”. The score of the Affective domain scored the highest mean, followed by the practical domain, with the cognitive domain being the lowest. There were significant differences in the clinical cultural competence behavior levels of the student nurses. These student nurses’ average cultural competency, reflected their own cultural competence, because they viewed their instructors as role models, enabling the acquisition of learning via knowledge transfer; Clinical Instructors teach the student nurses in circumstances as similar as possible to those in which nursing laboratory simulation to actual hospital setting will be employed.

Key words: Cultural competence, clinical instructors, student nurses, cultural assessment.

The process of acquiring cultural competence is imperative for nurses, faculty and student nurses learning their profession (Montenery et al., 2013). Nurses spend more time in caring for their patients than any other healthcare professional. They have a unique opportunity to influence access to care, quality of care and patient outcomes, and their knowledge on the patients’ culture, belief, and healthcare practices greatly influence their practice (Vicencio et al., 2015).Faculty and student nurse scare for their patients in the same way. As the faculty members mentor the students in their quest for knowledge, they spend most of their time at the bedside. This process requires cultural competence. According to Campinha-Bacote (2002), this is an ongoing process in which healthcare professionals continuously strive to achieve the ability to work effectively within the context of the client’s culture. Culture is a factor that can make a difference in promoting wellness, preventing illness, restoring health, facilitating coping and enhancing the quality of life for all individuals, families and communities (Jeffreys, 2015). Cultural competence, when applied to educators, is the ability to successfully teach students who from cultures other than their own successfully, to develop certain personal and interpersonal awareness and sensitivities along with certain bodies of cultural knowledge, and involves mastering a set of skills. Taken together, these skills generate effective cross-cultural teaching. In addition, Jeffreys (2015) stated that nursing educators are empowered to make an immense difference by introducing, nurturing and modeling optimal cultural competence. On the other hand, Montenery et al. (2013) emphasized that nursing educators should work with the intention of empowering students to provide holistic and comprehensive care, with the concept that cultural competence is essential in the delivery of comprehensive patient-centered care. Cultural competence as earlier defined by Jeffreys (2015) is an ongoing, multidimensional learning process that integrates transcultural nursing skills in all three learning domains- cognitive, practical, and affective- involving transcultural self-efficacy (confidence) as a major influencing factor, and that aims to achieve culturally congruent care.

Both nursing educators and their students must demonstrate an understanding that people of diverse cultures and belief systems perceive health and illness according to their own view and respond differently to various symptoms, diseases and treatments. In addition, Douglas et al. (2014) elucidated that an individual’s knowledge of the impact of culture on attitudes, values, traditions, and behaviors affects their health-seeking behaviors.

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), one of the Muslim countries in the Middle East, has its own unique culture, beliefs and health practices. For the Saudi family, considerable cultural clashes can arise when patients are hospitalized and receive care from health-care professionals who do not understand Saudi cultural beliefs and values. In addition, the Arab News network (www.arabnews.com; February 4, 2016) reported data from the Saudi Department of Statistics and Information that the population of the KSA comprises 21.1 million native Saudis and 10.4 million expatriates: nearly 33% of the total population. Of these, 75% are Indian, Pakistani, Egyptian, Bangladeshi and Filipino while the remaining 25% are Sri Lankan, Yemini, Jordanian/Palestinian, Indonesian, Sudanese, Syrian, Turkish, and Westerners. These data clearly show that the country has a very diverse population, which means that professional nurses, as well as clinical instructors and nursing students, are challenged with a wide variety of cultural, linguistic and health literacy barriers (Singleton and Krause 2009). Hence, cultural beliefs and practices concerning the health and illness in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia can only be addressed by healthcare providers through advanced knowledge of the Saudi population culture (Johnson et al., 2017). According to Campinha-Bacote (2002), cultural awareness is the self-examination and in-depth exploration of one’s own cultural and professional background. In this context, nursing educators and clinical instructors must be aware of their own biases, prejudices, and assumptions about individuals who are different from them culturally, so that they will not enforce their own cultural beliefs and patterns of behavior on the nursing students whom they supervise and teach. Bednarz et al. (2010) stressed that nursing educators serve as role models for their students through their own efforts to expand the scope and depth of cultural competence, and in demonstrating the ongoing quest for excellence that needs to be a part of professional nursing practice.

The Saudi nursing curriculum covers a five-year period (10 semesters) for a bachelor’s degree, which is allocated to classes, laboratory work and clinical practice. Clinical practice is conducted on two to three days per week throughout the semester, wherein students are rotated to the different specialties of clinical practice (Mutair, 2015). Nursing students’ clinical practice is supervised by an officially designated clinical instructor, who has a dual role in the accomplishment of their role, which includes patient safety in the hands of the student learner, and facilitating students’ learning. Nursing students practice their skills directly on the patient, and that is why clinical instructors must be equipped with the knowledge and clinical competence required of a professional nurse along with their postgraduate degree and work experience to enrich knowledge and expertise. They are clinical teachers who are skilled, experienced nurses dedicated to maintaining and improving standards of patient care, and are concerned to help learners develop their potential as nurses. This is achieved through building good relationships, counseling, supporting, and advising, aside from demonstrating expertise in caring for patients because the patient’s life - or certainly his/her well-being - could be at risk (Mutair, 2015). This process does not consist merely of passing on information or knowledge, but is also mainly an expression of values and attitudes. What teachers usually get back from their students is what they themselves have brought to the teaching-learning process (Thanasoulas, 2002). Therefore, the quality of student learning is dependent not only on the type of clinical experience but also on the characteristics and skills of the teacher who facilitates learning (Mutair, 2015). University-based clinical instructors must be able to demonstrate cultural competency while teaching the students directly and giving indirect care to patients from different cultures. Cultural competence, according to Loftin et al. (2013), involves having the necessary attitudes, knowledge, and skills for the delivery of culturally appropriate care to a diverse patient population. According to Riyadh Arab News (www.alriyadh.com, dated June 13, 2014), there are 18,000 expatriate teachers in KSA universities, serving in various positions including professors, associate professors, assistant professors, lecturers and assistant lecturers. The University of Hail College of Nursing, located at Hail City, KSA, is one of those universities employing expatriate teachers. There are forty-five Filipino clinical instructors serving the college, both in the clinical and classroom settings. They were hired based on their relevant expertise.

The aim of this study was to determine the cultural competency of Saudi nursing students as rated by their clinical educators, who mentor and train them to become globally competitive, culturally aware professional nurses.

This is a descriptive/evaluative study aimed at determining differences between the levels of cultural competency of Saudi student nurses from the perceptions of their clinical instructors. The study was conducted at the College of Nursing, Hail University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Thirty full-time clinical instructors participated in this study out of the total population of thirty-six (83%). A purposive sampling technique was used, and the respondents were chosen because of their specific culture, skills and experience. The clinical instructor genders were equally distributed (50% female and 50% male), with the most common age range being 40 to 44 years (30%). Of these, 23 (76%) mostly worked at the medical surgical department, 28 (93%) were lecturer/nurse specialists, 27 (90%) with a Master’s degree. Eleven (37%) of them had 16 to 20 years of work experience in the academic field but most of them (27; 90%) had less than 1 to 5 years of experience in this healthcare institution. Nineteen (63%) of them had undertaken no formal education in transcultural nursing, and 22 (73%) of the respondents were not studying relevant education units. The research questionnaire was prepared based on the Cultural Competence Education Resource (CCER) toolkit authored by Jeffreys and Dogan (2012). The following research instruments were used based on the CCER:

1. A Demographic Profile Questionnaire was designed based on the Demographic Data Sheet for Nurses (DDSN), but with some adjustment for the University’s work position category, existing unit or department, and educational and work-experience requirement for employment.

2. The Cultural Competence Clinical Evaluation Tool-Teacher Version (CCCET-TV) comprised of 83-item questionnaire adapted from the Transcultural Self-Efficacy Tool (TSET), an instrument consisting of 83 items subdivided into three sections of cognitive, practical, and affective domains. This contained three subscales measuring different dimensions of students’ clinical cultural competence behaviors as rated by the teacher or their preceptor: extent of culturally specific care (Subscale 1, Cognitive Scale); cultural assessment (Subscale 2, Practical Scale); culturally sensitive and professionally appropriate attitudes, values, or beliefs including awareness, acceptance, recognition, appreciation and advocacy necessary for providing culturally sensitive professional nursing care (Subscale 3, Affective Scale). These were evaluated utilizing a Likert-type scale, rating answers from 1 (low competence level) to 10 (high competence level). A low rating was assigned to scores of 1 or 2 on the Likert scale, an average level to scores of 3 to 8, and a high level of competence to responses with scores of 9 or 10. Specific answers to the following questions were drawn from the questionnaire:

1. How can the profiles of the Filipino Clinical Instructors be described in terms of the following factors? Age; gender; work setting; current work position, highest educational attainment, work experience in academic or health-care institutions; previous college courses in transcultural nursing; and continuing education units in transcultural nursing.

2. What is the level of Saudi student nurses’ clinical cultural competence behavior in providing nursing care to patients from varied cultures? This evaluation included the extent of culturally specific care (cognitive scale), cultural assessment (practical scale), culturally sensitive and professionally appropriate attitudes, values, or beliefs in providing sensitive professional nursing care (affective scale) as rated by the clinical instructors.

3. Is there a significant difference among the level of Saudi student nurses’ clinical cultural competence behavior in providing nursing care to patients from varied cultures? This was evaluated in terms of the extent of culturally specific care (cognitive scale); cultural assessment (practical scale), and culturally sensitive and professionally appropriate attitude, values, or beliefs in providing sensitive professional nursing care (affective scale) as rated by the clinical instructors when grouped by their own demographic profiles.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Hail. Thereafter, consent for participation was obtained from respondents after they were notified of the aims, methods, anticipated benefits and potential hazards of the research. They were informed that they had the right to terminate their participation at any time and that confidentiality would always be maintained in terms of their responses.

Statistical analysis

The obtained data were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) for comparisons between the various groups in terms of specific questionnaire factors. This was used to determine any significant differences among the levels of Saudi student nurses’ clinical cultural competence, behavior in performing nursing care to the patients from varied cultures in terms of: the extent of culturally specific care, cultural assessment, culturally sensitive and professionally appropriate attitudes, values, or beliefs in providing sensitive professional nursing care, as rated by the clinical instructors and when grouped by their own demographic profiles. Differences between means were considered as significant at P ≤ 0.05.

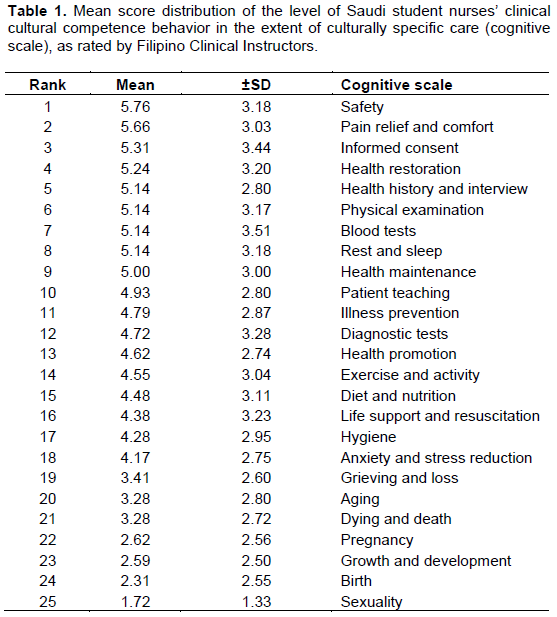

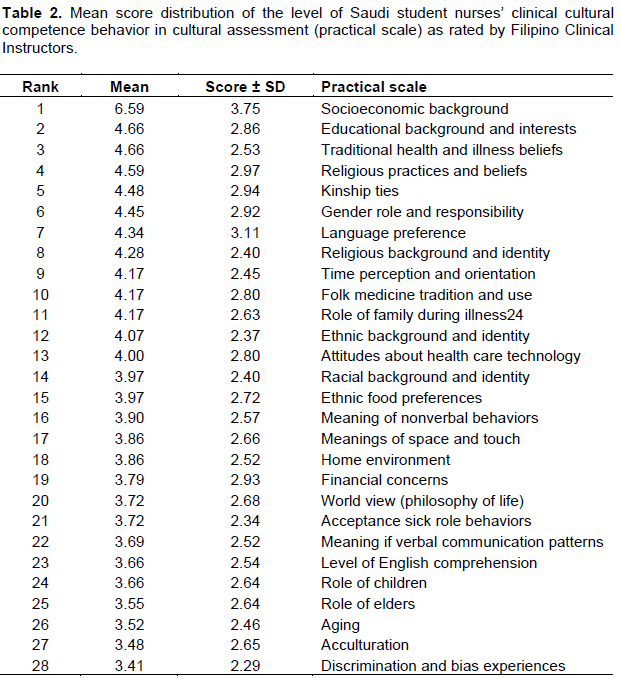

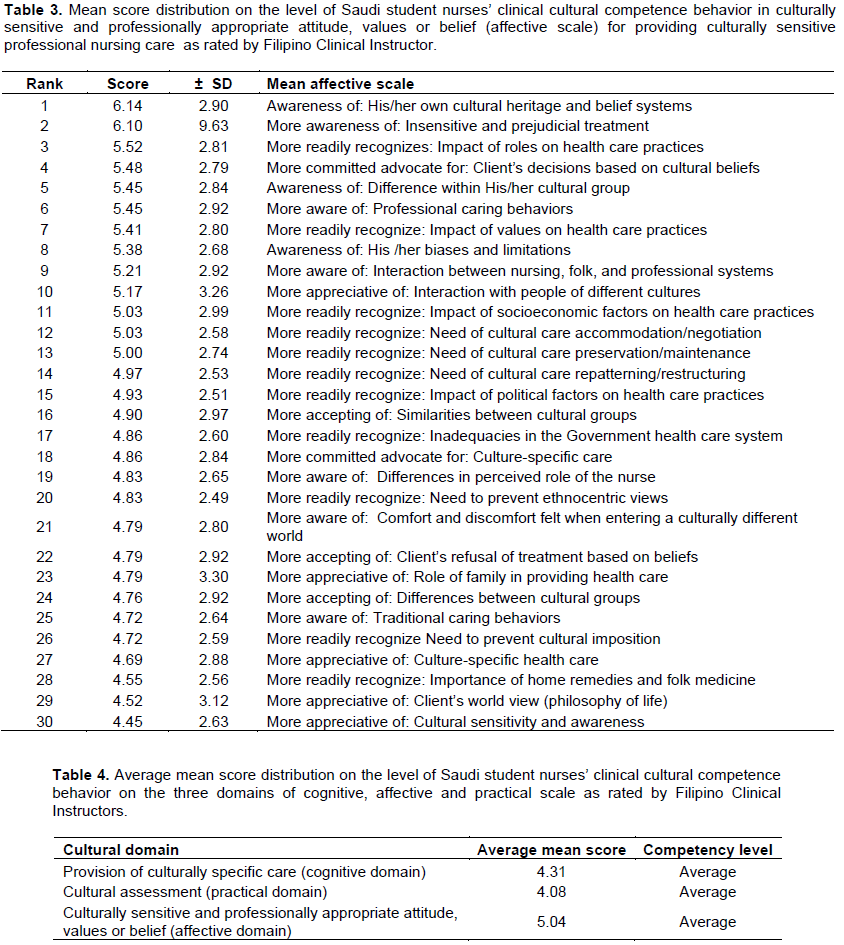

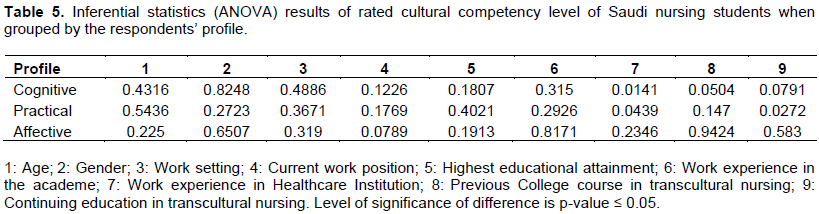

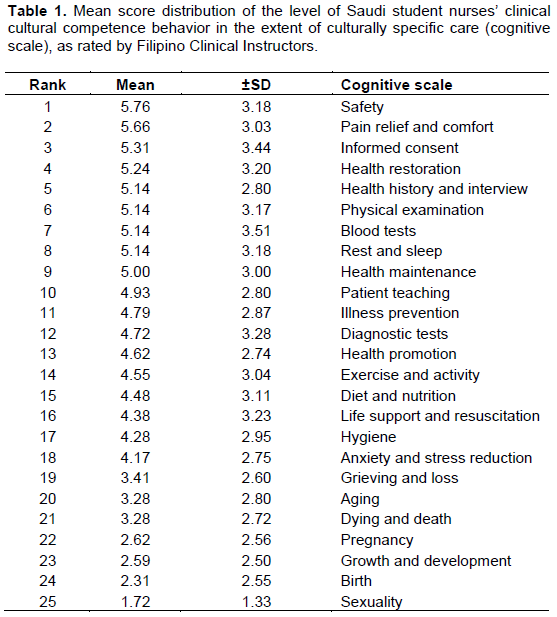

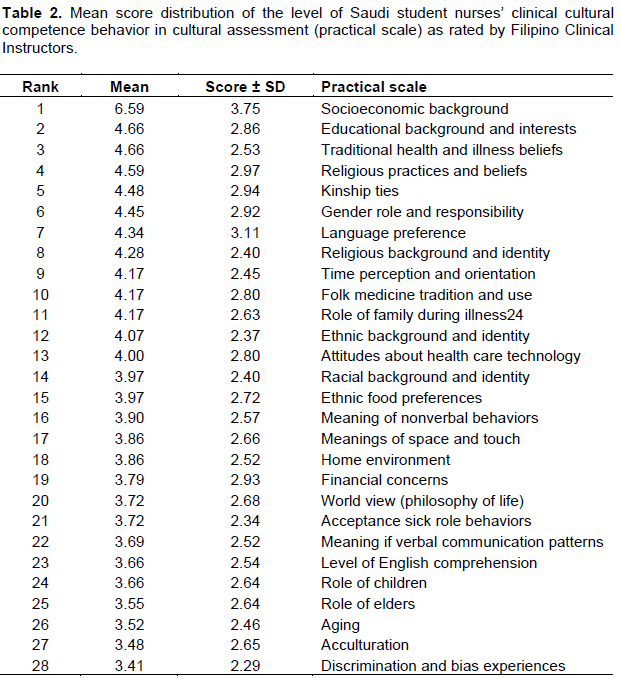

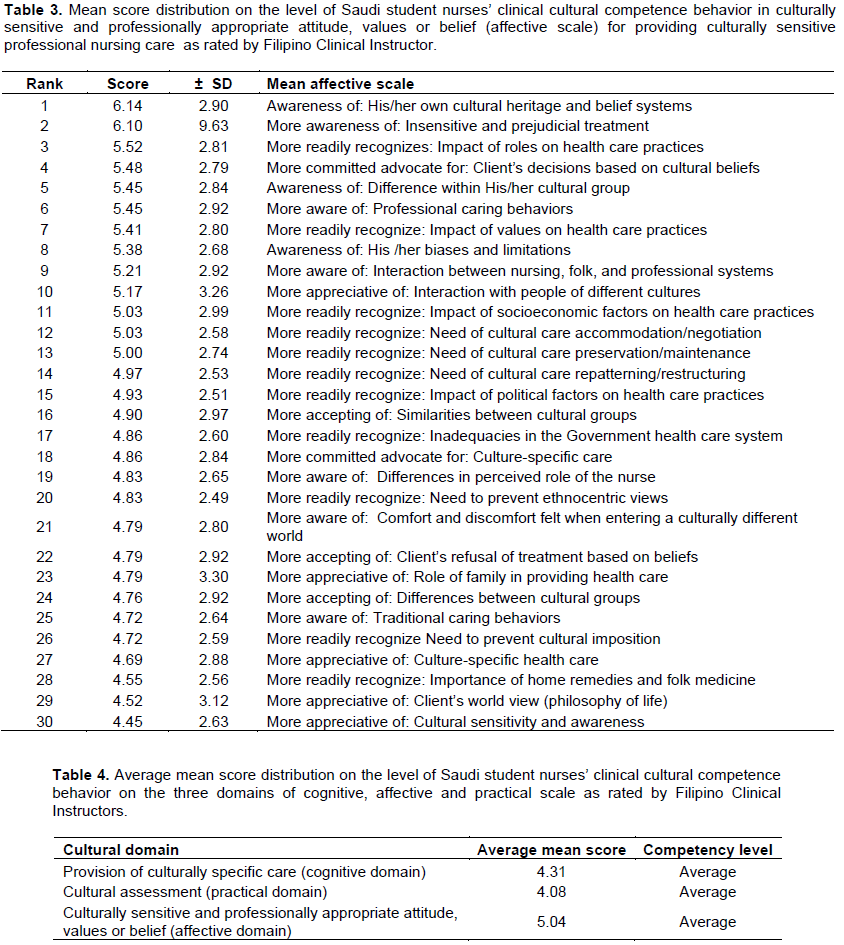

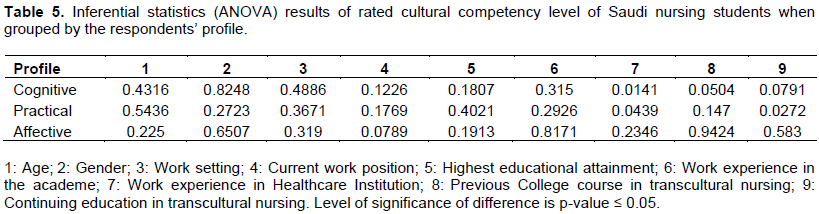

The mean score distributions for the level of Saudi student nurses’ clinical cultural competence behavior in the extent of culturally specific care (Cognitive Scale), as rated by the Clinical Instructors are shown in Table 1. Among the 25 studied variables, safety had the highest mean score of 5.76, followed by relief of pain and discomfort with a total mean score of 5.66 and informed consent with a mean score of 5.31, while dealing with sexuality had the lowest score of 1.72 along with birth at 2.35. On the other hand, the mean score distribution on the level of Saudi student nurses’ clinical cultural competence behavior in the cultural assessment (Practical scale) as rated by Filipino Clinical Instructors is presented in Table 2. Socioeconomic background had the highest mean score of 6.59 followed by educational background and interest with a mean score of 4.66, and the third in rank is traditional health and illness beliefs with 4.66 mean score, while discrimination and bias experience had the lowest mean score of 3.41, acculturation with 3.48 and 3.52 for aging. While in Table 3, the mean score distribution on the level of Saudi student nurses’ clinical cultural competence behavior in culturally sensitive and professionally appropriate attitude, values or belief (Affective scale) for providing culturally sensitive professional nursing care as rated by Filipino Clinical Instructor was shown. The results revealed that student nurses’ clinical cultural competence behaviour in culturally sensitive and professionally appropriate attitude, values or belief (affective scale) falls on average level in all items mentioned at affective scale and were rated average on the level of competency scale by their clinical instructors. They are aware, they accept, appreciate, and recognize the importance of one's cultural values, and beliefs in the provision of nursing care. Moreover, awareness of his/her own cultural heritage and belief systems top the rank with a mean score of 6.14, followed by more aware of insensitive and prejudicial treatment with 6.10 mean score and the third one is: more readily recognizes the impact of roles on health care practices with a mean score of 5.52, while the “more appreciative of: Cultural sensitivity and awareness” obtained the lowest mean of 4.45, “More appreciative of: Client’s world view” (philosophy of life) has a mean score of 4.52, and the “more readily recognize: Importance of home remedies and folk medicine” is 4.55 mean score presents the average mean score of the three scales of cognitive, practical and affective competency levels. It shows that affective scales got the highest average score of 5.04, followed by the cognitive scale with 4.31 average score and the practical scale got the lowest average of 4.08, which falls on the average level of cultural competency (Table 4). Table 5 presents the inferential statistics (ANOVA) results on the level of Saudi student nurses’ clinical cultural competence behavior rating when grouped by Filipino Clinical Instructor‘s demographic profile. The results show that there are significant differences on the rated level of Saudi student nurses’ clinical cultural competence behavior when grouped by Filipino Clinical instructor demographic profile (p ≤ 0.05), this only shows that Filipino Clinical Instructors’ method of rating the student nurses varies and affects student nurses’ competency level.

The Saudi nursing students in the eyes of their clinical instructors had average cultural competency levels in the provision of safety, relief of pain and discomfort, as well as in eliciting informed consent to particular treatments. Informed consent, confidentiality, privacy, autonomy, safety, respect, treatment choice, refusal of treatment, and participating in an agreed treatment plan are specified in most patients’ bills of rights (Habib and Al-Siber 2013), while patient safety is an essential and vital component of quality nursing care (Ballard, 2003). This shows that the Clinical Instructors could inculcate into their students, their knowledge on the patients’ bill of rights and patient safety, which is vital in the provision of nursing care. This is in accord with the study of Alsulaimani et al. (2014) on the cognitive competency of Filipino nurses working at Taif City, wherein the provision of safety to patients was associated with education and training levels. Nurses are for the most part altruistic and strive to do what is morally right in the service of human beings and society (Roy and Jones, 2006). On the other hand, relieving patient from pain and discomfort is fundamental to nursing care. According to Kolcaba’s Comfort Theory (2010), nursing is described as the process of assessing the patient’s comfort needs, developing and implementing appropriate nursing interventions, and evaluating the patient’s comfort needs following nursing interventions. In this study, the Clinical Instructors had clearly instilled basic knowledge in the minds of the Saudi nursing students on addressing the comfort needs of the sick patient upon initial encounter or assessment. Thus, they were aware that a person in pain cannot respond readily to the assessment process, because the tendency of the patient in pain or in discomfort is avoidance (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2001). Informed consent is another tenet of “patient rights” wherein the patient has the right to be fully informed of any nursing or medical procedures to be provided as well as their diagnosis and treatment plan (Almoajel, 2012). However, these students had poor cultural competency levels in terms of dealing with sexuality. This can be attributed to language barriers, because the clinical instructors were not proficient in the Arabic language and found it difficult to ask questions of the patients in terms of sexuality and the birthing process, and vice versa. The patients also had difficulty in understanding the English language, so the nurse educators/clinical instructors could not discuss sexuality or birth processes in detail in front of the patient, while coaching the nursing students. This is consistent with the study by Karout et al. (2013) on Saudi Arabian women’s experience and perception of maternal health services, that the biggest problem discussed by most women was that of linguistic diversity; not only the difference between the English and Arabic languages but extending to the accents of non-English speakers such as Indians, Filipinos and Pakistanis. In addition, the study conducted by Albagawi (2014) on examining barriers and facilitators to effective nurse-patient communication within the Saudi Arabian cultural context found that effective communication was not achieved because of many complex and overlapping personal, professional and organizational factors. Furthermore, according to Schyve (2007), differences in language and cultural differences are barriers to effective communication, resulting in low health literacy. Alsulaimani et al. (2014), in their study of cognitive competency of Filipino nurses working at some hospitals of Taif City, revealed that aside from language barriers, shyness and reluctance of Saudi patients to discuss sexuality and birth are factors to consider, because they are hesitant to disclose detailed information about themselves and their families. Being conservative, they can be embarrassed by questions on their sexual relationships and other personal matters. Karout et al. (2013) found in their study of Saudi Arabian women’s experiences and perception of maternal health services that “the presence of non-Muslim service providers did not satisfy them because they believed that Muslim service providers will not look at their uncovered bodies especially their genitalia unless there is a need for that, and they will be conscious uncovering themselves”. Thus, the Clinical Instructors found it difficult to create scenarios for the students to experience and participate in the learning process because of the patient’s culture. Consequently, this lack of opportunity for the Saudi nursing students to perform the task expected of them decreased their self-efficacy. As Bandura (2006) stressed, “If a person sees someone similar to them succeed, it can increase their self-efficacy, and also, seeing someone fail can lower self-efficacy”. Furthermore, according to Bandura (2006), “positive and negative experiences can influence the ability of an individual to perform a given task”. This is one reason why the clinical instructors perceived Saudi nursing students’ cultural competency level to be low in terms of discussing sexuality and birth as they have little knowledge in these particular concepts because of lack of the opportunity to perform in the practice care setting. This is in agreement with the study conducted by Lofmark and Wikblad (2001) that opportunities to practice different tasks and understanding the total picture facilitate the development of learning, while supervision that lacks continuity and lack of opportunities to practice hinders development of learning. In addition, a supportive clinical environment is one factor for enabling an effective clinical experience, which includes the atmosphere of a clinical placement unit, and the relationships shared with clinical staff supervisors and mentors (Lawal et al., 2016).

This study shows that, these Saudi student nurses had only average cultural competency, according to the ratings by the clinical instructors that reflected their own level of cultural competence. This was because nursing students view their clinical instructors as their role models and their learning acquisition was a result of knowledge transfer. These clinical instructors demonstrated competence in teaching and were able to role model cultural nursing even without previous knowledge or continuing education in transcultural nursing. Their academic preparation and expertise in the clinical area had significant impacts on student learning ability.

The role of clinical instructors in the learning development of nursing students is crucial as they greatly influence students’ learning processes. Interactions with their clinical instructors, peers and patients contribute to the students’ professional value systems. Therefore, provision of environments wherein the nursing students will experience all aspects of nursing roles will increase their self-confidence, professional values and clinical skills. The cultural competency of the nursing students will advance as they continuously provide nursing to culturally diverse patients. Clinical instructors must always emphasize to the students that “knowledge of the role of culture in health and illness” is essential for the development of culturally sensitive communication skills, while awareness of one’s own cultural health beliefs and practices in the performance of nursing care will develop culturally congruent communication skills as well as the development of skills in identifying variations between and within cultures.

The findings suggest that all clinical instructors must be included as respondents in the same study at the same locale to measure the student nurses’ clinical and cultural competence behavior aiming to establish a strong basis for transcultural nursing. This must be included in the curriculum, and self-evaluations of the student nurses and clinical instructors’ cultural competence must also be studied. Continuous updating on transcultural nursing for all clinical instructors is recommended to enrich their knowledge and skills in this field.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Albagawi BS (2014). Examining barriers and facilitators to effective nurse-patient communication within a Saudi Arabic cultural context. Doctoral dissertation, RMIT University, Australia.

View

|

|

|

|

Almoajel AM (2012). Hospitalized patients' awareness of their rights in Saudi governmental hospital. Middle-East J. Sci. Res. 11(3):329-335.

|

|

|

|

American Academy of Pediatrics (2001). The assessment and management of acute pain in infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatrics 108(3):793-797.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Alsulaimani AA, Vicencio DA, Ruiz FB, Elsheikh HA (2014). Cognitive competency of Filipino nurses working in some hospitals of Taif City, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Egypt. J. Hosp. Med. 57:384-394.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Ballard KA (2003). Patient safety: a shared responsibility. Online J. Issues Nurs. 8(3):4.

|

|

|

|

Bandura A (2006). Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents. pp. 307-337.

|

|

|

|

Bednarz H, Schim S, Doorenbos A (2010). Cultural diversity in nursing education: Perils, pitfalls, and pearls. J. Nurs. Educ. 49(5):253-260.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Campinha-Bacote J (2002). The process of cultural competence in the delivery of healthcare services: A model of care. J. Transcult. Nurs. 13(3):181-184.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Douglas MK, Rosenkoetter M, Pacquiao DF, Callister LC, Hattar-Pollara M, Lauderdale J, Milstead J, Nardi D, Purnell L (2014). Guidelines for implementing culturally competent nursing care. J. Transcult. Nurs. 24(2):109-121.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Habib FM, Alâ€Siber HS (2013). Assessment of Awareness and Source of Information of Patients' Rights: a Crossâ€sectional Survey in Riyadh Saudi Arabia. Am. J. Res. Comm. 1(2):1-9.

|

|

|

|

Jeffreys MR, Dogan E (2012). Evaluating the influence of cultural competence education on students' transcultural self-efficacy perceptions. J. Transcult. Nurs. 23(2):188-197.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Jeffreys MR (2015). Teaching cultural competence in nursing and health care: Inquiry, action, and innovation. 3rd Edn, Springer Publishing Company, New York, USA.

|

|

|

|

Johnson JM, MacDonald CD, Oliver L (2017). Recommendations for healthcare providers preparing to work in the Middle East: A Campinha-Bacote cultural competence model approach. J. Nurs. Educ. Pract. 7(2):25-30.

|

|

|

|

Karout N, Abdelaziz SH, Goda M, AlTuwaijri S, Almostafa N, Ashour R, Alradi H (2013). Cultural diversity: A qualitative study on Saudi Arabian women's experience and perception of maternal health services. J. Nurs. Educ. Pract. 3(11):172-182.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Kolcaba K (2010). An introduction to comfort theory. In the comfort line.

View

|

|

|

|

Lawal J, Weaver S, Bryan, V, Lindo JL (2016). Factors that influence the clinical learning experience of nursing students at a Caribbean school of nursing. J. Nurs. Educ. Pract. 6(4):32-39.

|

|

|

|

Lofmark A, Wikblad K (2001). Facilitating and obstructing factors for development of learning in clinical practice: a student perspective. J. Adv. Nurs. 34(1):43-50.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Loftin C, Hartin V, Branson M, Reyes H (2013). Measures of cultural competence in nurses: An integrative review. Sci. World J. 1-10.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Montenery SM, Jones AD, Perry N, Ross D, Zoucha R (2013). Cultural competence in nursing faculty: A journey, not a destination. J. Prof. Nurs. 29(6):e51-e57.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Mutair AAl (2015). Clinical Nursing Teaching in Saudi Arabia Challenges and Suggested Solutions. J. Nurs Care S1:007.

|

|

|

|

Roy SC, Jones DA (2006). Nursing knowledge development and clinical practice: opportunities and directions. Springer Publishing Company, New York, USA.

|

|

|

|

Singleton K, Krause E (2009). Understanding cultural and linguistic barriers to health literacy. Online J. Issues Nurs. 14(3):4.

|

|

|

|

Schyve PM (2007). Language differences as a barrier to quality and safety in health care: The Joint Commission perspective. J. Gen. Int. Med. 22(2):360-361.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Thanasoulas D (2002). What do teachers bring to the teaching-learning process?

View

|

|

|

|

Vicencio DA, Alsulaimani AA, Ruiz FB, Elsheikh HA (2015). Affective competency of Filipino nurses working in the hospitals of Taif City Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Nurs. Midwifery 7(4):46-53.

Crossref

|