ABSTRACT

Adolescence is a critical stage in human life. Adolescents’ perception of the impact of condom use on sexual behaviour has been studied in developed countries. However, not much is known about this phenomenon in Ghana. The study investigates the perception of adolescents regarding the impact of condom use on sexual behaviours. Simple random and stratified sampling techniques were employed to select the study respondents. The data were analysed using descriptive and inferential statistics. The study revealed that adolescents’ knowledge level about condom use was above average (>2.50). Again, the adolescents’ knowledge level about condom use predicted their sexual behaviours (β = 0.159, p=0.000). It is concluded that adolescents possess adequate knowledge about condom use. It is recommended that more stakeholders should be involved in the provision of knowledge on condom use among adolescents in Ghana.

Key words: Adolescents, adolescence, perception, knowledge level, condom use, sexual behaviours, Ghana.

Adolescence is an inevitable stage in human development as it serves as a turning point in the growth and development cycle of every human. It is one of the major stages since it presents many physical and emotional changes (Maqbool et al., 2019). The World Health Organisation (WHO) sees adolescence as the second decade in a person’s life, which is characterised by physical and psychological changes coupled with tremendous changes in how a person interacts socially as well as the relationships that are cultivated (WHO, 2009). Lewin (1939) defines adolescence as the transition from childhood to adulthood.

Over the past years research focus has been on sexual behaviour, social media usage by adolescents for sexual and reproductive health (SRH) and sexually transmitted infections (S.T.I) prevention (Adzovie and Adzovie, 2020:Rob et al., 2006;Sieving et al., 2002), and there is extant literature on adolescent sexual behaviour especially in developed countries. For instance the impact of family structure, parent-adolescent relations as well as parental

monitoring on adolescent sexual behaviour in European countries (Lenciauskiene and Zaborskis, 2008). Pedersen and Samuelsen (2003)conclude that since more adolescents have become sexually active, the resultant effect will be risky sexual behaviour (Slap et al., 2003). In sub-Saharan Africa, even though urban youth and adolescents with higher educational background use condoms, more adolescents are at risk of contracting HIV/STI due to insufficient or unavailability of condoms (Doyle et al., 2012).

Globally, the relevance of the discourse on the impact of condom use among adolescents regarding sexual behaviour cannot be overemphasised. Kalichman et al. (1998)stated that females from low-income communities mostly, do not ask their male partners to use condoms due to the perception that doing so may erupt some violent reactions from their male partners (Jemmott and Hacker, 1994: Thato et al., 2003). Support from parents, personal risk perception as well as self-efficacy contribute to the decision by adolescents in Cameroon to use condoms (Meekers and Klein, 2002).

Issues regarding adolescent sexual behaviour vis-a-vis adolescence are known to be age-long yet many people are believed not to be equipped with the challenges that hover around this period of human development. WHO (as cited in Boamah, 2012) indicates that, adolescence can be a challenging phase in life. People growing up at this stage have the responsibility of identifying themselves in the society they are found. Their youthful vigour predisposes them to a lot of exploration and risk-taking behaviours (Tarrant et al., 2001). These developmental changes compel adolescents to try new things including their sexual urges which eventually lead some adolescents to unavoidable problems. Bingenheimer et al. (2015) indicate that reproductive and sexual health problems attributable to sexual behaviours among adolescents such as early initiation of sex, lack of condom or other contraceptive use, multiple partners, and high risk partners are widespread among adolescents and young adults in sub-Saharan Africa because adolescents within this part of the world are believed to be less knowledgeable about contraceptives. Globally, the lack of useful adolescent sexual health education has brought about the high rates of adolescent-related problems such as unplanned pregnancies and sexually transmitted diseases (United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), 2007).

According to Bernhardt et al. (2005), the medical and social consequences of adolescent sexual activity are a national health concern for many countries. Kirby and Brown as cited in Kirby (2002) report that the menace of AIDS as well as the threat of other Sexually Transmitted Diseases (S.T.Ds) and pregnancy calls for grave concern. The situation appears to be different in Ghana because culturally, it is almost impracticable for students to be given condoms through school counsellors to prevent sexual-related problems. The Ghanaian culture frowns upon this act. Although it is unclear whether condoms are given to adolescents in schools, it is possible adolescents may be using condoms due to the inadequacy of sex education in this domain in Ghana. Sexual health promotion including Human Immunodeficiency Virus / Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS) prevention is most emphasised in Ghana because of religious and cultural values (Takyi, 2011). Adolescents are said to have raging hormones that drive their sexual desires (Doku, 2012). These sexual desires are then dramatized regarding teen sex and seen as a site of danger and risk (Arnett, 2007).

A report by Awusabo-Asare et al. (2017) indicated that SRH education topics are integrated into two core and two elective subjects; but those in the core subjects are limited in scope, and the overall approach emphasizes abstinence. However, teachers who are tasked to teach SRH reported challenges to teaching SRH topics effectively, including lack of time, lack of appropriate skills and inadequate teaching materials. This makes the quest for information on sexuality for adolescents through the school system inadequate (Awusabo-Asare et al., 2017).

Also, in Ghana, it has been documented that about 5000 adolescent girls became pregnant in the Central Region in 2017 (Nabary, 2017). The report corroborates a news report which captures a survey conducted by the National Service Personnel Association (Asiedu-Addo, 2017). The high rate of STDs and unplanned adolescent pregnancies in the Cape Coast Metropolis calls for an investigation into adolescents’ perception about contraceptives especially condom use as well as the impact this perception(s) has on adolescent sexual behaviour in the Cape Coast Metropolis.

Generally, the study is aimed at investigating the perceptions of adolescents regarding condom use and its impact on their sexual behaviours. Specifically, the study sought to: find out the knowledge level about condom usage among adolescent students in the Cape Coast Metropolis; assess the impact of condom-use on sexual behaviours of adolescent students; find out how condom use can improve the sexual behaviour of adolescent students; and examine the gender differences in condom use and sexual behaviours of adolescent students. In order to achieve these objectives, the following research questions (RQs) and hypotheses were formulated.

RQ 1. What is the knowledge level of adolescent students in Cape Coast Metropolis about condom use?

RQ 2. What is the impact of the knowledge of condom use on adolescents in the Cape Coast Metropolis’ sexual behaviours?

RQ3.How can condom use improve the sexual behaviour of adolescent students in the Cape Coast Metropolis?

H1: Male and female students will differ in their knowledge level on condom use.

Adolescence, adolescents and sexual behaviour discourse is an unending one. Literature relevant to the study has been reviewed under the following headings: adolescents’ knowledge level about condom use; condom use and sexual behaviours of adolescents; gender difference in adolescents’ knowledge level about condom use; and ways of improving/enhancing sexual behaviours of adolescent students.

The National Association of Social Workers in the United States, according to Gilbert (2001), opined that adolescence denotes the inception of bodily/erotic development and procreative ability in people. It is a stage that is characterized by many developmental changes. According to Larson and Wilson (2004), a thorough understanding of adolescence as a period in human development in society depends on information from various perspectives, including psychology, biology, history, sociology, education, and anthropology. From the above perspectives it is clear that adolescence is viewed as a transitional period between childhood and adulthood. To extend the discussion of transition, Coleman and Roker (1998) are of the view that adolescence is a period of multiple transitions involving education, training, employment and unemployment, as well as transitions from one living circumstance to another. Adolescence is believed to be marked by increased rights and privileges for individuals as a result of developmental changes (Van Den Bos et al., 2015). While cultural variations exist for legal rights and their corresponding ages, considerable consistency is found across cultures. According to Casamassimo et al. (2012), many cultures define the transition into adult-like sexuality by specific biological or social milestones in an adolescent’s life. Fields further indicates that, adolescents’ sexual socialization is highly dependent on whether their culture takes a restrictive or permissive attitude toward teen or premarital sexual activity.

Adolescents’ knowledge level about condom use

Generally, knowledge level influences perceptions. Speroff and Fritz (as cited in Akpan et al., 2014) report that since 1900, knowledge and application of contraception have been encouraged and promoted and in 1960s, contraception teaching and practice became part of the programme in academic medicine. According to Tarkang and Bain (2015), Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) remains the region hardest hit by the HIV/AIDS pandemic than any other in the world, largely due to high-risk behaviour and neglect of potential preventive measures. This has led to most adolescents resorting to the use of condoms to prevent the HIV/AIDS canker. Unwanted pregnancy, sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and their adverse health consequences among adolescents are widespread public health problems worldwide that calls for the knowledge of condoms (Yazdkhasti et al., 2015). An estimated 19 million new STDs occur each year in the United States of America of which 50% are among persons between the ages of 15 and 24 (CDC, 2008). Hearst and Chen (as cited in Tarkang and Bain, 2015) indicate that the correct or right knowledge and consistent condom use whether male or female, has been acknowledged to be effective towards successful prevention of sexually transmissible infections (S.T.Is), including HIV/AIDS that come as a result of sexual behaviours. Tarkang and Bain (2015), in Cameroon among adolescents, reveal that majority of the adolescents in Cameroon have appreciable knowledge about condoms and their usage. However, in practice, these adolescents do not use condoms. This may be dangerous because their attitudes may expose them to HIV/AIDS.

Also, Akpan et al. (2014) reveal that currently, the level of awareness and knowledge about condoms as a means of contraception and preventive measure against contracting STDs/HIV has increased among adolescent students in Nigeria. They attest that evidently, 100% of the respondents reported having knowledge about condom and how it is used. However, their findings were attributed to the peculiarity of the demography of respondents (adolescents sampled were from one of the most educated communities in Nigerian). Migosi et al. (2013) reveal that majority of adolescents in secondary schools in Kenya are sexually active and they actively use condoms, hence their knowledge level is above average as the study reveals that adolescents especially, males use condom in order to reduce risks of sexually transmitted infections and unwanted pregnancies. In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Masoda and Govender (2013) report that 137 (99.0%) of respondents studied knew what condoms were. However, they were of the view that this high knowledge level about condom usage among adolescents sampled could be due to governments and non-governmental organisations’ (NGOs) intensive efforts at educating adolescents about condoms, H.I.V and S.T.Is. Furthermore, most participants (76.0%) knew that condoms prevented HIV/STIs and unwanted pregnancies, and that it was important to use a condom every time that they had sexual intercourse.

Condom use and sexual behaviours of adolescents

Cates and Stone (as cited in Gilbert, 2001) report that condom use decreases the rate of acquisition of HIV. To corroborate this, Celentano et al. (1998)conclude that incidences of HIV AIDS infection declined among young military men in Thailand as a result of the implementation of ‘100% condom program’. Also, according to Shafii et al. (2004), condom use is known to decrease sexually transmitted infections. In furtherance to this, Blake et al. (2003) report that making condoms available and allowing their use in high schools protects sexually active adolescents from contracting STDs. However, Parsons et al. (2000)report that perceived benefits of sex without condom (unprotected sex) better determines the sexual behaviour of late adolescents. From the foregoing, it is evident that the merits of condom use among adolescents far outweigh that of non-usage because it can help adolescents maintain their healthy lifestyles as they continue to grow.

Gender differences in adolescents’ knowledge level about condom use

The issue of gender differences in condom use and sexual behaviour seem inconsistent. According to Closson et al. (2018), girls have higher sexual refusal self-efficacy, while boys have higher condom use self-efficacy. In studies measuring Condom Use Self-Efficacy that compared gender differences in South Africa, had higher Condom Use Self-Efficacy compared to boys (Awotidebe et al., 2014; Boafo et al., 2014). However, among 19 analyses measuring CUSE, nine found that boys had higher CUSE than girls (Slonim-Nevo and Mukuka, 2005; Tenkorang and Maticka-Tyndale, 2014), three reported that girls had higher Condom Use Self-Efficacy compared to boys (Louw et al., 2012; Sayles et al., 2006), three found no gender differences in Condom Use Self-Efficacy (Puffer et al., 2012), and four did not report descriptive differences in Condom Use Self-Efficacy by gender (Louw et al., 2012; Njau et al., 2007; Taylor et al., 2007).

Leland and Barth (1992) assert that females are more likely than males to discuss sexuality topics with parents, and they equally engage in sexual intercourse more frequently. In that same study, it was reported that adolescent males are more likely to use birth control during their first sexual encounter, and to use a condom during their last sexual encounter. Furthermore, males knew more about using condoms correctly and their role in preventing sexually transmitted diseases (Leland and Barth, 1992). A study by Prata et al. (2005) in Angola reveals that a larger proportion of males than of females indicated that they had always used condoms with all of their partners in the three months preceding the survey. This synopsis above puts the male adolescents in pole position against female adolescents when it comes to condom usage in sexual behaviours.

Ways of improving/enhancing sexual behaviours of adolescent students

To avoid doubt and the quest not to compound issues with adolescent development, there is the need for well-thought strategies, well-informed modalities to be put in place to improve and enhance adolescent students’ sexual behaviours. Programmes and activities that serve as motivations for adolescents are of great importance to nurturing them against risk-taking sexual behaviours as well as enhancing the way adolescents handle themselves against sexual pressures. According to Kirby (2002), social scientists and educators have proffered a wide variety of explanations for how schools can reduce sexual risk-taking behaviours. To Kirby, educators concerned with adolescent sexual behaviour have suggested that schools should structure adolescent students’ time and limit the amount of time that students can be alone and engage in sex. According to Bennell et al. (2002), school-based sex education is an encouraging platform for introducing many adolescents to vital health information and life skills that can avert accidental conditions and sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Shrestha et al. (2013) indicate that although sex education looks important to improving adolescents’ sexual behaviours, it is challenged in many jurisdictions, particularly in developing countries like as it is severely controlled by social and cultural taboos on discussing issues related to sex whether in school or home. In a related study, Amponsah et al. (2018) found that school-based sex education is important because majority of adolescent students in the Wa Municipality in Ghana agree that sex education would have a positive effect on their social lives. There is an urgent need for effective strategies to reduce the number of problems adolescents encounter (Ahern and Bramlett, 2016).

Manlove et al. (2015) in their study among American high school students reveal that parent-youth relationship programmes are particularly effective at influencing the sexual behaviours and reproductive health outcomes among adolescents. According to Miller et al. (2001), the important role that parent-adolescent relationships provide includes parental monitoring and parent-adolescent communication as they help influence adolescents’ sexual and reproductive health behaviours. According to Ajidahun (2013), parental monitoring during pre-adolescence affects the age at which adolescents start and begin sexual activity. He further states that adolescents who are knowledgeable about sex are more likely to use contraceptives consistently, and are more likely to postpone sexual intimacy. According to Ventura et al. (as cited in Ajidahun, 2013), adolescents who receive counselling regarding sexual behaviour from school or community programmes have a better chance of avoiding pregnancy and other risks connected with sexual behaviours or activity. To Ajidahun, sexual behaviour counselling needs to be a shared responsibility and should not be left in the hands of parents alone. Teachers, professional counsellors and more importantly the society should be involved. According to Germain et al. (2015), young people have a fundamental human right to participate in matters that affect their lives. Meaningful participation is defined as seeking information, expressing ideas, taking an active role in different steps of a process, being informed or consulted on decisions concerning public interest, analysing situations, and making personal choices. Several factors, including age, gender, social and economic class, ethnicity, race, sexual orientation, and HIV status, are key determinants of what role young people see for themselves in society and the ways in which they participate in programs and policies. Arop et al. (2019) opine that care given to adolescents by health professionals in a variety of settings, including communities, schools, and public health and acute care clinics affords them many opportunities to improve adolescents’ sexual behaviours.

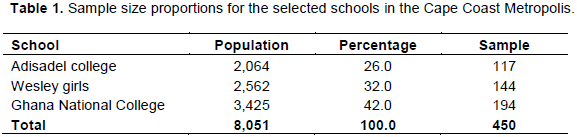

This study employed the descriptive survey design. The target population was 20,063 and comprised all Senior High School adolescent students in the Cape Coast Metropolis. The accessible population was 8,051 and comprised three (3) randomly selected schools. A sample of 450 adolescent students (aged between 14-19 years) was used for the study. The sample size was based on a five percent of the accessible population suggested by Ary et al. (2009). In their view, 5 to 20% of a population can serve as an adequate sample for quantitative studies. Two single sex schools (male school and female school) and one mixed school (boys and girls) were randomly sampled for the study. Stratified sampling technique was used to cater for the population differences in as much as comparison between male and female respondents was considered. Finally, respondents were selected to participate in the study using the systematic sampling technique with the help of the students’ register. Table 1 presents the various schools and their sample proportions: The instrument used in collecting the data for the study was the ‘Sexual Behaviour Inventory’ a close-ended type paper-based questionnaire developed by the researchers and scored based on 4-point Likert-type scale. The scale was measured in agreement and disagreement dimensions, where 1=Strongly Disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Agree and 4=Strongly Agree. The questionnaire had some negative statements, which were reversely scored as 4=Strongly Disagree, 3=Disagree, 2=Agree and 1=Strongly Agree. Out of this, a cut-off point was established following the formula [1+2+3+4=20/4=2.50]. The questionnaire comprised four sections with 31-items. Section A of the questionnaire had only 1-item measuring gender as a socioeconomic background. Section B of the questionnaire contained 12-items measuring knowledge level on condom use. Section C of the questionnaire contained 11-items measuring effect of condom use on sexual behaviour and section D with 7-items of the questionnaire measured ways in improving sexual behaviours. Pre-testing of the questionnaire was conducted at two senior high schools (St Augustine’s College and Holy Child Senior High School) on 60 students who did not make up the final sample to establish the consistency and reliability of the instrument. In establishing reliability of the questionnaire, Cronbach Alpha was used, where pre-testing and final administration generated reliability coefficients of .75 and 0.71 respectively. The researchers administered the questionnaire themselves and the respondents were informed of the study purpose (oral informed consent), privacy of data collected (with exception of results), assured of their confidentiality in providing information, anonymity of personalities and free will to withdraw from the study for personal reasons. The data gathered in the study were analysed using descriptive (means and standard deviations) and inferential statistics (linear regression, and independent samples t-test) with the aid of Statistical Package for Service Solution (SPSS) version 23. Before this, the data were screened and missing values were not realised. The analysis done was based on a 100% return rate.

The purpose of the study is to find out the perceptions of adolescents in the Cape Coast Metropolis about the impact of condom use on their sexual behaviours. The results are presented descriptively (means and standard deviations) and inferentially (linear regression and independent samples t-test) after satisfying the assumptions of the analytical tools. The presentation was done based on the researcher’s questions and the hypothesis that guided the study.

Research Question One: What is the knowledge level of adolescent students in Cape Coast Metropolis about condom use?

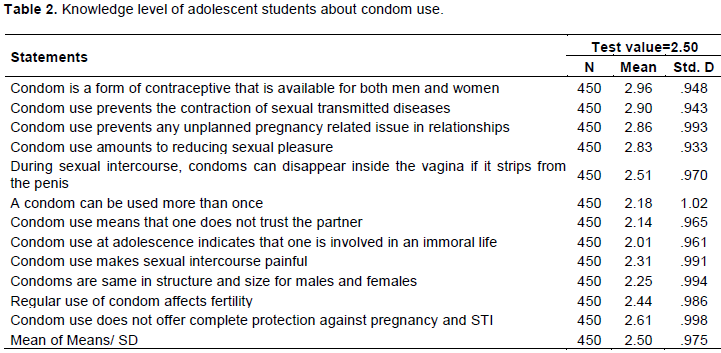

The purpose of this research question was to assess the knowledge level of adolescent students about condom use. To achieve this, means and standard deviations were used to assess the adolescents’ knowledge level. The results are presented in Table 2.

As represented in Table 2, the results show that generally, adolescents in the Cape Coast Metropolis have some knowledge about condom use. This can be seen from a mean score which was greater than the test value (2.50). For instance, it was evident that most of the adolescents in the Cape Coast Metropolis are aware that condom is a form of contraceptive that is available for both males and females (M=2.96, SD=0.948, n=450). Also, it was revealed that adolescents in the Cape Coast Metropolis are aware that condom use prevents the contraction of sexually transmitted diseases (M=2.90, SD=0.943, n=450).These findings confirm that of Akpan et al. (2014) in Nigeria, which revealed that adolescents attested that they knew about condom and how it is used. Conversely, the current study defied the general assertion made by Tarkang and Bain (2015) that Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) remains the region hardest hit by the HIV/AIDS pandemic due to high-risk behaviour and neglect of potential preventive measures. There may be exceptions to the problem in some countries within the sub-region of SSA because knowledge of condoms may vary geographically.

The results also indicated that most of the adolescents in the Cape Coast Metropolis know that condom use prevents any unplanned pregnancy related issue in relationships (M=2.86, SD=.993, n=450). In another related result, the adolescents specified that condom use reduces sexual pleasure during sexual intercourse (M=2.83, SD0.933, n=450). The adolescents in the Cape Coast Metropolis further demonstrated their knowledge level that condoms can disappear inside a female’s vagina when it strips from the male’s penis (M=2.51, SD=0.970, n=450). The revelation of the current study seems not different in other studies such as Mucugu et al. (2013) and Masoda and Govender (2013), which revealed adolescents in Kenyan secondary schools were sexually active; hence they use condoms so that they could protect themselves from sexual-related problems. Few of the items scored a mean less than the test value of 2.50, indicating that adolescents in Cape Coast Metropolis disagreed with some statements in the aspect of condom use. For example, they disagreed that one condom can be used more than once (M=2.18, SD=1.02, n=450). In addition, they disagreed that condom use means that one does not trust one’s partner (M=2.14, SD= 0.965 n=450) and condom use indicates that one is spoilt or immoral (M=2.01, SD=0.961, n=450). Again, the respondents disagreed that condoms are very painful when used (M=2.31, SD=.991); it was also disagreed that condoms are same in structure and size for male and females (M=2.25, SD=0.994). Finally, the respondents disagreed that regular use of condom affects fertility (M=2.44, SD=0.987); they agreed that condom use does not offer complete protection against pregnancy and S.T.I (M=2.61, SD=0.998). From the foregoing, it can be concluded that adolescent senior high school students in Cape Coast Metropolis knowledge level about condom use was average as their observed grand mean of 2.50 was similar to the criterion mean of 2.50. Not surprising anyway, indeed, condoms are not reusable; they protect rather than expose people to consequences of promiscuous sexual activities. The current study findings corroborate with Tarkang and Bain (2015) who revealed that majority of Cameroonian adolescents were having appreciable knowledge about condoms and their usage. Similarly, the findings confirm Mucugu et al. (2013)’s study among adolescents, which revealed that majority of the students were sexually active and they actively used condoms, so their knowledge was above average. The respondents’ view re-echoed what is known about condoms and their usage.

Research Question Two: What is the impact of the knowledge of condom use on adolescents’ sexual behaviours in Cape Coast Metropolis?

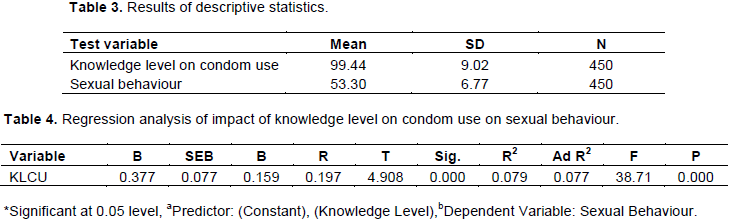

The study sought to determine the impact of adolescents’ knowledge level of condom use on their sexual behaviours. To make this possible, standard multiple regression was used for the analysis. Table 3 presents the results. Table 3 shows the descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) of the test variables. The results indicated that adolescents’ knowledge level on condom use produced the highest mean and standard deviation (M=99.44, SD= 9.02) while sexual behaviour produced the lowest mean (M=53.30, SD=6.77). Deducing from the findings, it is clear that adolescents’ knowledge level about condoms and their usage was higher than exhibiting sexual behaviours. However, this has less to offer as whether the knowledge level could predict sexual behaviour, hence further regression observation. Table 4 presents regression results.

Table 4 indicates the result of regression analysis of knowledge level on condom use against sexual behaviour. Symbols interpretations are the unstandardized beta (B), the standard error for the unstandardized beta (SE B), the standardized beta (β), the t-test statistic (t), the significant value (sig), the ANOVA value (F), the ANOVA p-value (p), the correlation (r), the R square value (R2), and the Adjusted R Square value (Ad R2).The result shows that knowledge level on condom use (r=.197) has significant positive relationship with adolescents’ sexual behaviour. The results of the regression indicated the predictor (knowledge level in condom use) explained 7.9% of the variance (R2=0.079, F (2.908) =38.71, p=0.000). It was found that knowledge level in condom use significantly predicted adolescents’ sexual behaviour (β = 0.159, p=0.000). The findings presupposed that as one becomes knowledgeable in condoms and their usage, it is likely one might engage in sexual activities. Conversely, this revelation defeats the idea that the availability and use of condoms among adolescents does not increase adolescent sexual activity, rather, condoms protect adolescents from contracting sexually transmitted diseases (Blake et al., 2003).

Research Question 3: How can condom use improve the sexual behaviours of adolescent students in Cape Coast Metropolis?

To enumerate results for this research question, means and standard deviations were deemed appropriate for the analysis. Table 5 presents the accumulated results. As illustrated in Table 5, the results give indication that some measures can be used to improve the use of condom on sexual behaviour of adolescent students in the Cape Coast Metropolis. The results, however, showed that some of the measures could be more effective and more conducive to the adolescent students than others. For instance, the adolescent students agreed that adolescents’ sexual behaviours can be improved through the use of clinical-based programs that are championed by nurses and other health professionals (M=2.60, SD= 1.06, n=450). The revelation buttressed the fact that health facilities does not only offer services regarding sickness but could go a long to educate adolescents on sexual lives and reproductive health. Therefore, it is not surprising that clinical-based programs provided in a variety of settings could offer opportunities for adolescents to improve their sexual behaviours as suggested by Maria et al. (2017).

They further suggested that adolescents’ sexual behaviours can be improved by taking them through sex education (M=2.90, SD= 1.01, n=450). To get more evidence, the adolescent students established that adolescents’ sexual behaviours can be improved by encouraging and motivating them to avoid amoral sexual activities and think of school and academics (M=2.85, SD= 1.00, n=450). The adolescent students were also of the view that adolescents’ sexual behaviours can be improved by adopting health-based programmes to educate them on the best practices (M=2.71, SD= 0.989, n=450). In fact, sex education can be offered in many ways by many institutions including educational psychologists and counsellors. These professional groups’ contribution to adolescent development is unabated because they possess appreciable knowledge about adolescent development and its related stage problems. It is therefore, not surprising that Ventura et al. (as cited in Ajidahun, 2013) assert that adolescents who receive counselling regarding sexual behaviour stood a chance of avoiding sexual-related problems.

In furtherance to the above measures, the adolescent students pointed out that adolescents’ sexual behaviours can be improved by counselling them on the values of remaining pious and abstaining from sexual intercourse at their age (M=2.71, SD= 0.989, n=450). Measures like adolescents’ sexual behaviours can be improved by using adolescent role models in championing their course so that they can learn from such role models (M=2.63, SD= 1.02, n=450). Lastly, the measure that adolescents’ sexual behaviours can be improved through programmes that are parent-oriented where parents can educate their adolescents on the consequences of teenage amoral sexual relationships was least approved by the adolescents (M=2.78, SD= 1.00, n=450). The findings can be concluded that in general, adolescent students’ knowledge about condoms and their usage can go a long way to improve their sexual behaviours as they continue to grow in societies that allow inter-sexual interaction among people. As revealed by the current study above, the issues are not quite different from what was found in Amponsah et al. (2018)’s study. The study revealed that adolescents agreed when sex education is provided to them, it would have a positive effect on their social lives because they could be trained to manage their sexual desires. Furthermore, the study findings support Manlove et al. (2015) that among American high school students, parent-youth relationship programmes are particularly effective at influencing the sexual behaviours and reproductive health outcomes among adolescents.

Research hypothesis

H1: There are significant differences between male and female students with regard to their knowledge level on condom use.

One of the objectives of the study was to determine the differences between male and female students with regard to knowledge level on the use of condoms. Table 6 presents the results. As depicted, the means and standard deviation give slight indication that male students (Mean= 19.39, SD=3.38, n=239) have more knowledge on the use of condom than female students (Mean=19.31, SD=3.50, n=211. However, a critical look at the t and p-value showed that no significant difference existed between male and female students [t (448) =0.236, p = .814, p>0.05, n=450, 2-tailed).The findings refute that of Prata et al. (2005) in Angola, that male students were knowledgeable in condom use than female students. More so, the findings debunked a study finding by Leland and Barth (1992) which states that female students were more knowledgeable in condom use than male students because they have discussed sexuality topics with parents and engaged in sexual intercourse more frequently.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

From the foregoing findings, it can be concluded that the knowledge level of adolescent students in Cape Coast Metropolis on condom use is adequate. The revelation calls for a worry, looking at the volatile and boisterous nature of today’s adolescents. In part, the revelation is appreciable but it is likely to propel adolescents to try out sexual activities if care is not taken and proper sex education is not provided for them. These adolescents may mistakenly presume that the use of condoms is 100% for sexual protection; hence, the possibility of adolescent students engaging in unprotected pre-marital sexual relationships cannot guarantee complete prevention of sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Based on this, it can be said that adolescent students’ knowledge level in the use of condoms will predict their sexual behaviours. Therefore, it is recommended that stakeholder institutions such as Planned Parenthood Association of Ghana (PPAG), School Counsellors and Education Psychologists guide adolescent students on condom usage as their knowledge level may lead them to practice sexual activities without recourse to potential consequences like sexual infections. The stakeholders’ role could be done by educating adolescents on sexuality issues. As adolescents, they keep growing and would need sex education in order to guard against any unplanned pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections/diseases, which may hamper their progress socially and academically regarding sexual relationships. Forging ahead, it is recommended that research works should also focus on curiosity and sexual behaviour among in-school adolescents.

Implications for counselling

Based on the findings, it is important that school guidance and counselling programmes are encouraged as these adolescents may be vulnerable to social pressures towards sexual activities. Having a functioning guidance and counselling programme in schools will help curtail the dangers of adolescents’ sexual exploration. With this, every school needs to be equipped with the right human capital that can offer guidance services to students so that they can be guided as they progress on the growth ladder.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Adzovie DE, Adzovie HR (2020). Impact of Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Education. In D. C. Karpasitis (Ed.), 7th European Conference on Social Media (pp. 10-18).

|

|

|

|

Ahern NR, Bramlett T (2016). An update on teen pregnancy. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services 54(2):25-28.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ajidahun BO (2013). Sex counselling and its impacts on adolescents' moral behaviour. American International Journal of Social Science 2(4):34-39.

|

|

|

|

|

Akpan UB, Ekott MI, Udo AE (2014). Male condom: Knowledge and practice among undergraduates of a tertiary institution in Nigeria. International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 2(1):032-039.

|

|

|

|

|

Amponsah OM, Mahama I, Kwaw R, Amponsah AM (2018). Perceived effects of sex education on adolescents' social lives in the Wa Municipality. Journal of Innovation in Education of Africa (JIEA) 2(2):82-102.

|

|

|

|

|

Arnett JJ (2007). Emerging adulthood: What is it, and what is it good for? Child Development Perspectives 1(2):68-73.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Arop FO, Chijioke ME, Owan VJ (2019). Adolescents' Perception Management and Attitudes Towards Sex Education in Secondary Schools of Cross River State, Nigeria. International Journal of Management Sciences and Business Research 8(3):32-38.

|

|

|

|

|

Ary D, Jacobs LC, Razavieh A, Sorensen C (2009). Introduction to research in education. Wadsworth: Engaged Publishing.

|

|

|

|

|

Asiedu-Addo S (2017). GHANA: Unbelievable- Central region teenage pregnancy remains high as girls now exchange sex for fish.

|

|

|

|

|

Awotidebe A, Phillips J, Lens W (2014). Factors contributing to the risk of HIV infection in rural school-going adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 11:11805-11821.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Awusabo-Asare K, Stillman M, Keogh S, Doku DT, Kumi-Kyereme A, Esia-Donkoh K, Bankole A (2017). From paper to practice: Sexuality education policies and their implementation in Ghana. New York: Guttmacher Institute.

|

|

|

|

|

Bennell P, Hyde K, Swainson N (2002). The impact of the HIV/AIDS epidemic on the education sector in sub-Saharan Africa. Brighton: Centre for International Education, University of Sussex.

|

|

|

|

|

Bernhardt B, Gick B, Bacsfalvi P, Adlerâ€Bock M (2005). Ultrasound in speech therapy with adolescents and adults. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics 19(6-7):605-617.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bingenheimer JB, Asante E, Ahiadeke C (2015). Peer influences on sexual activity among adolescents in Ghana. Studies in Family Planning 46(1):1-19.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Blake SM, Ledsky R, Goodenow C, Sawyer R, Lohrmann D, Windsor R (2003). Condom availability programs in Massachusetts high schools: relationships with condom use and sexual behavior. American Journal of Public Health 93(6):955-962.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Boafo IM, Dagbanu EA, Asante KO (2014). Dating violence and self-efficacy for delayed sex among adolescents in Cape Town, South Africa. African Journal of Reproductive Health 18(2):46-57.

|

|

|

|

|

Boamah EA (2012). Sexual behaviours and contraceptive use among adolescents in Kintampo, Ghana. African Journal of Reproductive Health 11(2):1-73.

|

|

|

|

|

Casamassimo PS, Fields Jr. HW, McTigue DJ, Nowak A (2012). Pediatric dentistry: Infancy through adolescence, 5/e. Elsevier India.

|

|

|

|

|

Celentano DD, Nelson KE, Lyles CM, Beyrer C, Eiumtrakul S, Go VF, Khamboonruang C (1998). Decreasing incidence of HIV and sexually transmitted diseases in young Thai men: Evidence for success of the HIV/AIDS control and prevention program. Aids 12(5):F29-F36.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Closson K, Dietrich JJ, Lachowsky NJ, Nkala B, Palmer A, Cui Z, Miller, CL (2018). Sexual self-efficacy and gender: A review of condom use and sexual negotiation among young men and women in Sub-Saharan Africa. The Journal of Sex Research 55(4-5):522-539.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Coleman JC, Roker D (Eds.). (1998). Teenage sexuality: Health, risk and education. Psychology Press.

|

|

|

|

|

Doku D (2012). Substance use and risky sexual behaviours among sexually experienced Ghanaian youth. BMC Public Health 12(1):571.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Doyle AM, Mavedzenge SN, Plummer ML, Ross DA (2012). The sexual behaviour of adolescents in subâ€Saharan Africa: Patterns and trends from national surveys. Tropical Medicine and International Health 17(7):796-807.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Germain A, Sen G, Garcia-Moreno C, Shankar M (2015). Advancing sexual and reproductive health and rights in low-and middle-income countries: Implications for the post-2015 global development agenda. Global Public Health 10(2):137-148.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gilbert DJ (2001). HIV-affected children and adolescents: What school social workers should know. Children and Schools 23(3):135-142.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Jemmott LS, Hacker CI (1994). Predicting intentions to use condoms among African-American adolescents: The theory of planned behavior as a model of HIV risk-associated behavior. Ethnicity and Disease 2(4):371-380.

|

|

|

|

|

Kalichman SC, Williams EA, Cherry C, Belcher L, Nachimson D (1998). Sexual coercion, domestic violence, and negotiating condom use among low-income African American women. Journal of Women's Health 7(3):371-378.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kirby D (2002). The impact of schools and school programs upon adolescent sexual behaviour. Journal of Sex Research 39(1):27-33.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Larson R, Wilson S (2004). Adolescence across place and time: Globalization and the changing pathways to adulthood.

|

|

|

|

|

Leland NL, Barth RP (1992). Gender differences in knowledge, intentions, and behaviours concerning pregnancy and sexually transmitted disease prevention among adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health 13(7):589-599.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lenciauskiene I, Zaborskis A (2008). The effects of family structure, parent-child relationship and parental monitoring on early sexual behaviour among adolescents in nine European countries. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 36(6):607-618.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lewin K (1939). The field theory approach to adolescence. American Journal of Sociology 44:868-897.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Louw J, Peltzer K, Chirinda W (2012). Correlates of HIV risk reduction self-efficacy among youth in South Africa. The Scientific World Journal 2012.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Manlove J, Fish H, Moore KA (2015). Programs to improve adolescent sexual and reproductive health in the US: A review of the evidence. Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics 6:47.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Maqbool M, Khan M, Mohammad M, Adesina MA, Fekadu G (2019). Awareness about Reproductive Health in Adolescents and Youth: A Review. Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research 1-5.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Masoda M, Govender I (2013). Knowledge and attitudes about and practices of condom use for reducing HIV infection among Goma University students in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Southern African Journal of Epidemiology and Infection 28(1):61-68.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Meekers D, Klein M (2002). Determinants of condom use among young people in urban Cameroon. Studies in Family Planning 33(4):335-346.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Migosi J, Mucugu P, Mwania J (2013). Condom use, awareness and perceptions among Secondary School students in Kenya. International Journal of Asian Social Science 3(8):1658-1677.

|

|

|

|

|

Miller BC, Benson B, Galbraith KA (2001). Family relationships and adolescent pregnancy risk: A research synthesis. Developmental Review 21(1):1-38.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Nabary JK (2017). Central region is second in teenage pregnancies and child marriage. Report in Ghana News Agency portal. Retrieved from

View

|

|

|

|

|

Njau B, Mtweve S, Barongo L, Manongi R, Chugulu J, Msuya M, Jalipa H (2007). The influence of peers and other significant persons on sexuality and condom-use among young adults in northern Tanzania. African Journal of AIDS Research 6(1):33-40.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Parsons JT, Halkitis PN, Bimbi D, Borkowski T (2000). Perceptions of the benefits and costs associated with condom use and unprotected sex among late adolescent college students. Journal of Adolescence 23(4):377-391.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Pedersen W, Samuelsen SO (2003). New patterns of sexual behaviour among adolescents. Tidsskrift for den Norske Laegeforening: Tidsskrift for Praktisk Medicin, ny Raekke 123(21):3006-3009..

|

|

|

|

|

Prata N, Vahidnia F, Fraser A (2005). Gender and relationship differences in condom use among 15-24-year-olds in Angola. International Family Planning Perspectives 31(4):192-199.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Puffer ES, Drabkin AS, Stashko AL, Broverman SA, Ogwang-Odhiambo RA, Sikkema KJ (2012). Orphan status, HIV risk behavior, and mental health among adolescents in rural Kenya. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 37(8):868-878.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Rob U, Ghafur T, Bhuiya I, Talukder MN (2006). Reproductive and sexual health education for adolescents in Bangladesh: Parents' view and opinion. International Quarterly of Community Health Education 25(4):351-365.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sayles JN, Pettifor A, Wong MD, MacPhail C, Lee SJ, Hendriksen E, Coates T (2006). Factors associated with self-efficacy for condom use and sexual negotiation among South African youth. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 43(2):226.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Shafii T, Stovel K, Davis R, Holmes K (2004). Is condom use habit forming? Condom use at sexual debut and subsequent condom use. Sexually Transmitted Diseases 31(6):366-372.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Shrestha RM, Otsuka K, Poudel KC, Yasuoka J, Lamichhane M, Jimba M (2013). Better learning in schools to improve attitudes toward abstinence and intentions for safer sex among adolescents in urban Nepal. BMC Public Health 13(1):244.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sieving RE, Oliphant JA, Blum RW (2002). Adolescent sexual behavior and sexual health. Pediatrics in Review 23(12):407-416.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Slap GB, Lot L, Huang B, Daniyam CA, Zink TM, Succop PA (2003). Sexual behaviour of adolescents in Nigeria: Cross sectional survey of secondary school students. British Medical Journal 326(7379):15-18.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Slonim-Nevo V, Mukuka L (2005). Child abuse and AIDS-related knowledge, attitudes and behavior among adolescents in Zambia. Child Abuse and Neglect 31(2):143-159.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Takyi M (2011). Nurture experiences and career aspirations of junior high school students in Berekum Municipality. Doctoral dissertation, University of Cape Coast.

|

|

|

|

|

Tarkang EE, Bain LE (2015). Factors that influence utilization of the female condom among senior secondary school female students in urban Cameroon. American Journal of Health Research 2(4):125-133.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Tarrant M, North AC, Edridge MD, Kirk LE, Smith EA, Turner RE (2001). Social identity in adolescence. Journal of Adolescence 24(5):597-609.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Taylor M, Dlamini SB, Nyawo N, Huver R, Jinabhai CC, De Vries H (2007). Reasons for inconsistent condom use by rural South African high school students. Acta Paediatrica 96:287-291.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Tenkorang EY, Maticka-Tyndale E (2014). Assessing young people's perceptions of HIV risks in Nyanza, Kenya: Are school and community level factors relevant? Social Science and Medicine 116:93-101.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Thato S, Charronâ€Prochownik D, Dorn LD, Albrecht SA, Stone CA (2003). Predictors of condom use among adolescent Thai vocational students. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 35(2):157-163.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

United Nations Population Fund (2007). State of World Population: United Nations Population Fund. Retrieved from

View

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Van Den Bos W, Rodriguez CA, Schweitzer JB, McClure SM (2015). Adolescent impatience decreases with increased frontostriatal connectivity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(29), E3765-E3774.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

WHO (2009). Strengthening the health sector response to adolescent health and development. In Springer Reference.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Yazdkhasti M, Pourreza A, Pirak A, Abdi F (2015). Unintended pregnancy and its adverse social and economic consequences on health system: A narrative review article. Iranian Journal of Public Health 44(1):12.

|

|