ABSTRACT

By definition, disasters are natural phenomena that occur unexpectedly. Moreover, throughout the ages, human communities have experienced numerous disasters and the expectation is that there will be as many more in the coming years. On a daily basis, there are reports of earthquakes, hurricanes, and flood disaster news on TVs, radios, and other news media. Therefore, it is important to understand the effects of natural disasters on individuals as well as on community-based institutions. For these reasons, in particular, the purpose of this study is to explore, understand and analyze the notorious 1999 Marmara Earthquake on people’s daily lives and social institutions. It is expected that peoples and countries within the earthquake zone can learn lessons from this Turkish Earthquake and draw some conclusions for the sake of their people’s mental health as well as help protect their social institutions in the event of such hard times.

Key words: Human dimensions of Earthquakes, Marmara earthquakes, social institutions after earthquakes, search and rescue efforts after earthquakes, natural disasters.

In recent times, especially among residents of areas prone to earthquakes, there has been a growing fear of the psychosocial aspects of disasters. Cataclysmic events, and earthquakes, in particular, have a wide range of consequences, ranging from physical injuries to the loss of social relationships, fear-arousal, and other unpredictable and highly psychological destruction. For this reason, environmental and clinical psychologists, psychiatrists, and epidemiologists over the years have conducted studies to outline various dimensional impacts of earthquakes (Galea et al., 2005; Bonanno et al., 2006; Bulut, 2018). In all those studies, earthquakes are said to pose one of the most dangerous types of natural disasters due to their life-threatening, unpredictabilities, and uncontrollable nature (Ba?o?lu and Mineka, 1992). For when they occur, they cause widespread devastation that leaves survivors at risk with injuries, loss of properties, homelessness, and dislocation (Liu et al., 2011; McCaughey et al., 1994). Furtheremore, traumatic events cause considerable fear and anxiety that the same disaster may happen again or the effect of the incident is always very real and available. There is also a phenomenan called “post traumatic growth”, after the disaster people get better and start to heal and after that they can feel some positive changes in themselves that internal feeling is also called “post traumatic growth” (Bulut, 2021).

Undoubtedly, the unfortunate eventualities of this phenomenon are the lack of advanced warning systems which creates confusion and shock, as people find themselves completely unprepared for earthquakes physically and psychologically. As previously stated, this study aimed to give a compendious picture, and analyze the notorious 1999 Marmara Earthquake on the lives of people and social institutions. Relevant studies and literature on the topic were identified, examined, and sorted out across numerous dimensions of earthquakes with the help of an electronic database. Terms used to identify relevant studies included but were not limited only to post-earthquake struggles, anxiety during earthquakes, loss of lives, love ones, business, and social institutions during earthquakes, and rebuilding after earthquakes. More importance was however given to studies with social and psychological impacts of earthquakes. At first, such works of literature were identified, followed by a detailed examination of their findings to determine their relevance to the study.

THE 1999 MARMARA EARTHQUAKES

Turkey is ranked eighth among top ten countries mostly affected by natural disasters (Guha-Sapir et al., 2012). In the recent past, most notably on the 17th of August 1999, a major earthquake of 7.4 on the Richter scale hit the northwestern part of Turkey. The tremor lasted approximately 45 s and was followed by several aftershocks and earthquakes over the next few months. The epicenter then was the portal town of Gölcük in ?zmit. Whereas the most severely affected area covered a diameter of 100 km from the epicenter. The disaster particularly hit the most heavily populated and industrialized cities in the area and affected a huge metropolitan, which covered approximately a distance of 500 km. This led to the death of 20,000 peoples and left half a million homeless. Many citizens living close to the epicenter were also subjected to severe traumatic experiences (Bulut, 2006).

Notwithstanding the above fore-mentioned casualties, the most widely broadcasted and stunning damage to any industrial facility occurred at a large petroleum refinery located in the town of Körfez, an industrial town very close to ?zmit. The refinery received international media attention because it burnt uncontrollably for several days. While the fire was burning out of control, people were evacuated from areas and collapsed buildings that were within 2 to 3 miles of the refinery where search and rescue efforts were ongoing. Train services being the main form of transportation in the area was interrupted due to the fire. Ironically, as the fire was burning and was expected to explode all tanks and the whole refinery plant, residents within the surrounding areas were not allowed to leave their homes and neighborhoods. Moreover, the fire burnt and kept spreading which eventually broke water pipelines, making it difficult for firefighters to quench the fire. However, the fire was eventually quenched and controlled 5 days after the earthquake by the drops of forms with the aid of an aircraft.

The above forewords of the never to be forgotten August 17th earthquake give a brief introduction of the notorious 1999 Marmara earthquake. In a general post-earthquake context, community anxiety is heightened by severing vital “lifelines” such as phone systems, thus making it difficult to locate loved ones. In most situations and during hard times such as earthquakes, localized lifeline damage can deprive communities of water, sewage, electricity, and gas (Durkin and Thiel, 1993). The interruption of such vital services during and after earthquakes does not only affect victims but also rescue teams and efforts. In a vivid examination of communication systems in the first few days after the Great Earth Japan Earthquake of 2011, Yamamura et al. (2014) attested to the fact that due to the damage and severely disabled communication infrastructure, the use of mobile phones, laptop computers, and landline phones to communicate were largely difficult. These difficulties were not only experienced by victims but also medical teams and rescue operators trying to communicate and pass vital information. Similar situations were observed in Turkey. This caused extra trauma and confusion for residents as phone lines and cell phones were disconnected for more than 10 days and shut down respectively. This induced a feeling of being trapped as residents felt they had nowhere to go.

Besides, with electricity reliability a problem in the region due to the earthquake, decreased bodies were both stored in makeshift morgues and the ?zmit Ice Rink. Victims who were not immediately identifiable were photographed for later identification. By the second and third day corpses started to smell very bad, leaving survivors and rescue teams with no option than to wear masks to avoid contagious diseases. Mass burials were later conducted after the 3rd day and continued until the 5th day. People under the debris were loaded onto trucks with bulldozers and carried outside of the town or dropped in seas in Yalova. Hence, many people did not see their dead relatives’ bodies. This created false hope, denial, and postponement of their grieving processes.

It was so tragic that all Turkish TV stations and many foreign media covered the news for almost two weeks In the U.S., CNN, NBS, and ABC headlined their first daily news with the Turkish earthquake and used the same topic in their special edition news/magazine programs mostly in prime time. The news showed people under the rubble, some screaming, asking for help, some missing part of their body, legs, or arms. Children were also seen crying as they watched the rescue efforts. Exposure to such disasters and painful experiences suddenly are highly likely predictors of psychological struggles. Past shreds of evidence on life after earthquakes show that posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among other psychological struggles affects close to 85% of survivors and victims' exposure to injuries and loss of body parts (Zhang and Ho, 2011). Most severely among the aged, children, and women.

People in the Marmara region have been multiply traumatized. The first trauma was the earthquake itself that they had to go through the second time. Followed by the uncensored widespread media coverage that continued for more than one month in Turkey on more than 15 TV stations. Children and adults had to watch rescue and recovery events in the immediate location; others saw them on TV and continuously heard other reports of the earthquake via other news channels. All mass burials and many funeral services were conducted under extensive television, newspaper, and radio coverage. The traumatizing scenes were extensively shown on TV, especially every evening on prime-time shows. The live broadcasts included: Victims frantically trying to lift heavy debris with their bare hands, human bodies partly protruding from rubbles, blood, hysterically crying mothers and children, survivors pleading for help, and chaos in general. All Turkish newspapers devoted most of their coverage to the earthquake, rescue efforts, and aid. This caused more sorrow, helplessness, and trauma for those who lost family members, friends, and acquaintances.

In their Earthquake Mental Health Analysis paper, Durkin and Thiel (1993) reported that following an earthquake, there is uncertainty among survivors to the extent that people are reluctant to reoccupy homes due to safety concerns. In substance, there is always a major concern on the part of homeowners coupled with tenants demanding reassurance from individuals and organizations with recognizable expertise that their homes are safe. Because such reassurance was lacking, many residents opted to evacuate their dwellings and relocate (Durkin and Thiel, 1993). This exact need was observed in the Turkish earthquake due to extreme fear and the fact that ground motion and lateral displacement due to earthquakes may cause deformation to buildings (Roghaei and Zabihollah, 2014). Thus, residents' concerns of reassurance and expert examinations of the usability of their homes were genuine. This uncertainty around the safety of buildings further delays recoveries and exacerbates the societal and economic effects of earthquakes as people continue to abandon homes and businesses (Goulet et al., 2015).

Unfortunately and to make matters worse, as rescue and search activities continued, scientists started speculating and making predictions of a possible aftershock earthquake in Istanbul (as it was described in the North Anatolian Fault Zone (NAFZ) earthquakes, where the aftershock moved gradually through the west). They even provided enough empirical data to show that the next biggest earthquake was going to hit Istanbul, the largest and most populous metropolitan city with a population of 15 million covering a metropolitan area of 200 miles. Therefore, there was (and still there is) constant panic and confusion among the residents of Istanbul and its surrounding areas. This panic was also escalated by the fact that government officials and private institutions gave drastically inconsistent briefings about the upcoming earthquake. Private television stations and media platforms used these as topics of arguments on daily basis for the sake of ratings.

This obviously was causing more confusion and distrust among the citizens of Istanbul and the Marmara Region. Finally, the director of one of the biggest Observatory Center, Kandilli, situated in Istanbul simply admitted to the fact that citizens living in an earthquake-prone zone must learn to be prepared and be alert at all times. This confession brought about more uncertainty, defenselessness, and confusion as well as distrust against government officials. After the 17 August earthquake, there were numerous aftershocks in the region. There were many rumors with regards to another expected big earthquake. Finally, the second earthquake on November 12 occurred which further escalated the fear and confusion.

After the initial experience, most of the 15 million people in the vast earthquake area remained outdoors, even if their houses had no damage. Many of them continued living in parks, gardens, and even street sidewalks, because of aftershock fear. This continued until November 12 when the second earthquake increased their fears. It was reported that almost the entire resident population stayed outside in tents during that winter. Mitchell and Holzer (2000) reported that injuries from the earthquake were mostly orthopedic, neurological, cuts, scratches, and bruising. Apparently, emotional trauma and shock did not come to anybody’s mind in the initial stages. Many of the injuries were in Istanbul. Frequent aftershocks also continued after the second earthquake. Therefore, many residents jumped out of their windows, which resulted in more leg and arm fractures.

Beyond the potential for physical destruction, one of the defining characteristics of a disaster is its potential for disrupting the social functioning of individuals and social institutions. For earthquakes, it does not only impact productions and business capital, and human casualties but adversely affects the dimensions of human and societal institutions (Belloc et al., 2016). From the University of Delaware, Disaster Research Center, Webb (2000) reported social damage in institutions, such as education, health care, transportation, economic production, distribution, and consumption that were heavily interrupted because of the damage to their physical buildings and of relocation problems. Similarly, earthquakes inflict damages to roads, telecommunication infrastructural, hospitals, and schools (Baytiyeh, 2014). Such occurrences have other negative financial impacts, making it especially more likely for poorer individuals and nations to remain in poverty (Hallegatte et al., 2017).

All the above-mentioned casualties were witnessed in the 1999 Marmara earthquake, as many schools, hospitals, governmental buildings, religious buildings, and community centers were wiped out. Many people had to be relocated and separated from their neighbors, relatives, and even immediate family members. The Turkish Social Security Administration (Sosyal Sigortalar Kurumu, SSK) reported that 150,000 workers lost their jobs, and this number did not include those in the trade and professional professions. The stress and worries coupled with injuries, loss, and damage to properties as a result of an earthquake can induce emotional distress. Even the non-injured can experience increased stress, anxiety, and depression as a direct or indirect consequence of the substantial damage that earthquakes cause (Durkin and Thiel, (1993). In an attempt to evaluate the relationship between social capital and mental health outcomes in post-disaster settings precisely earthquake, Tsuchiya et al. (2017) opined that individuals with low social capital, large scale losses, and those displaced were at greater risk of experiencing psychological distress.

As such, once search and rescue are dealt with, restorations of life and society after earthquakes prove that post-earthquake relocation is a complex process. Sometimes it involves staying in several different places until a permanent home is found again. The rebuilding process can take several years. In a special report posted on Global Press Journal, it is reported that 10 months after the 2015 earthquake in Nepal that destroyed over half a million houses, thousands of people still lived in tents and temporary shelters (Manandhar, 2016). Recent interviews with Turkish survivors revealed that it was very harsh for them to live in very small tents or prefabricated houses. Most of which is largely due to the kind of attachment they had developed with their belongings, home, neighborhood, and the fact that separation from them creates extreme stress and discomfort. This concept was described by Webb (2000) as “attachment to social place.” For this reason, place attachment or deep emotional connection with places are important experiences that create a sense of meaning. Across several works of literature, attachment to social place has proven to be relevant in whether an individual relocates (Gustafson, 2014), perceived resident quality, and safety (Bonaiuto and Alves, 2012).

Furthermore, homelessness and relocation are often described with the term, “relocation trauma.” Some psychologists are of the view that “relocation trauma” which everybody experiences even under normal conditions when moving to another home, or a new neighborhood causes very unfamiliar and uncomfortable feelings. Relocations and frequent change of place cause insecurity because of separation from home and belongings, the stress of living in settings with inadequate space, and the social stress of not living with relatives. Dislocated survivors in the region reported similar phenomena, just as what was explored in a study by Salcioglu et al. (2018). In that study, survivors of the 2011 Van earthquake in Turkey who had to relocate displayed several forms of relocation traumas. Those who had to relocate within the disaster region mostly had to deal with PTSD and depression symptoms but depression symptoms were only significant when dissatisfied with the emotional support received. To reduce such feelings of relocation traumas and other stress after the 1999 Marmara earthquake, efforts were made by Municipal officials to provide local transportation from tent cities to different points in the city, but these services could not cover all parts of the cities and were not also very convenient for most of the residents of the tent or prefabricated neighborhoods.

Therefore, they complained about the lack of social ties as they missed their friends and social routines. This brought about feelings of powerlessness and helplessness. The feeling of prolonged helplessness, losing control over one’s life, having very little to do, and loss of meaning in life to some extent kept escalating their lack of direction in life and depression levels. It is also important to note that the initial August 17, 1999 earthquakes in Turkey was followed by many aftershocks and finally with another earthquake on November 12, 1999. The 7.4 magnitude earthquake destroyed infrastructure of the Marmara region, resulting in unemployment, the exodus of a large proportion of the population, and shortage of electrical power, telephones, and social support over an extended period. These “secondary stressors” created substantial stress for the whole community. The survivors also experienced a “loss of community” and thus a degree of social support that can act as a buffer for the debilitating effects of the disaster. This prolonged chronic type of traumatic period is what is mostly referred to as “process trauma” (Terr, 1981).

In addition, many inhabitants left the area, especially those who had migrated from the east and the Black Sea areas. At least 30,000 gave official notice of their moves, but many more moved without formal notice to the administrative authorities. Many of the displaced persons who moved back to the East were largely migrant laborers who had moved to these highly industrialized places due to the employment opportunities on offer. Other victims who relocated from the area were the upper class who could afford a temporary vacation home along the Aegean region or in other large cities. It was widely reported that many people attempted leaving the disaster site, at least for a while. On the part of government officials, shortly after the disaster, the migration patterns were clearly understood but very little is known as to the exact numbers. Five weeks after the earthquake, it was reported that Adapazari, which previously had 200,000 residents before the earthquake, now had 50,000 to 70,000. For the second biggest earthquake on 12 November which was severely felt in the city of Bolu, after the earthquake, reports suggested that 25,000 people moved out of the city. The adverse effects of these earthquakes led to the layoff of 30,000 out of 51,000 workers according to the Social Security Administration reported.

All these sudden changes to population dimensions of places close to the earthquakes affected areas led to governmental concerns. Thus, a ‘general population count’ (census) was conducted by the Turkish Statistical Institute (DEI) on October 22, 2000, which also showed a pattern of population decrease in the earthquake-affected areas. According to the census data, although big cities in the affected area experienced a drastic population decrease, the surrounding villages and rural areas did not experience any decrease compared to the 1997 census. However, municipal official findings in the cities and small towns suggested that population decrease in the area ranged between 10 and 20 percent. As far as the total number of people that left the earthquake area is concerned, the 2000 census data indicated that 50,000 people had left the earthquake-hit areas (Table 1). However, the cities’ records revealed a migration of at least 150,000-200,000 people (DIE, 2000).

Reports on the adverse effect of the earthquakes also indicated that it affected organizations and their members (Durkin and Thiel, 1993) similar to earthquakes in other countries. In most cases, the impact of earthquakes on organizations includes direct physical damage to properties, loss or damage of stocks, interruptions of productions, and staff attrition (Mehregan et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2010). This earthquake in question significantly affected institutions as well as organizations. All education, health care systems, rescue and emergency organizations, and the Red Crescent were deeply paralyzed by the magnitude and suddenness of the disaster because some staff in these organizations simply left their current duty locations. Durkin and Thiel (1993) explained these events with the term “organizational bereavement.”

THE EFFECTS ON THE EDUCATION

Another social institution that is often disrupted in a disaster and that must be restored is education. The Marmara earthquake deeply affected the region’s educational activities. Experts reported that when the school schedule is interrupted, a certain amount of ambiguity and confusion is created; therefore, administrators always want to restart school as soon as possible. Doing so does not only puts students in school for regular hours, but also gives structure direction, and meaning as well as offers a return to their daily routines.

Originally, based on the Turkish national curricula that see to it that all schools start and close at the same time, schools were scheduled to resume on September 15, 1999. The earthquake struck almost one month before schools were scheduled to begin. Schools in many slightly affected areas began as they were scheduled. However, when the major aftershock occurred on that same day, all school openings were indefinitely postponed. In some areas, schools that were not heavily damaged began operations on October 4, 1999. With two big earthquakes occurring within some interval and another expected, parents and teachers were very anxious about school starting again.

In Istanbul, the National Director Center and Board of Education and the Istanbul Technical University faculty members checked every single school and made sure that it was safe to begin education. In heavily damaged areas, such as Gölcük and Adapazar?, schools were expected to begin in early November. The reasons why reopening of schools in Gölcük was delayed for such a lengthy period were (1) some of the schools were heavily damaged, thus prefabricated buildings and tent schools were needed to accommodate students; (2) many teachers and parents were scared of entering school buildings, even those school buildings that had not been badly damaged by the earthquake; and (3) it was unknown, as how many students were expected to return to school, as some of the parents had migrated to other parts of the country. Many students were also believed to have returned with their families to villages in the surrounding mountains from where they had come from.

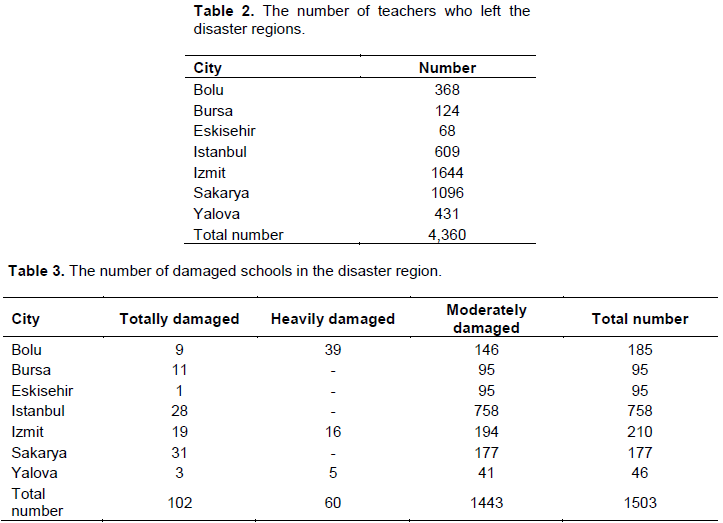

On the first anniversary, newspapers reported that the affected schools had not yet recovered from the earthquake’s devastating effects. As the earthquake led to the retirement of 36 teachers as well as the death of 1,387 working teachers. In addition, a total of 30,360 teachers also left the devastated regions (DIE, 2000). (Table 2).

The earthquake destroyed 102 schools including 31 in Sakarya, 28 in Istanbul, 19 in Kocaeli, 11 in Bursa, 3 in Yalova, and 1 in Eskisehir. Besides, 503 schools were moderately damaged and closed (Table 3). As opposed to a large number of ruined school buildings, in the first year, only 609 classrooms in 56 prefabricated school buildings were rebuilt. Even though right after the earthquake, restoration of buildings started and tent schools were abandoned; however, not all the restoration efforts were enough to recover and start the post-disaster school routine. All the above impacts of the 1999 Marmara on education were also felt in almost every country that had experienced earthquakes in the past years regardless of the size of the disaster. In Nepal, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Myanmar for instance, many children have lost months of education due to earthquakes (Ireland, 2016).

Another greater area of concern after an earthquake is its negative psychological effects. Being so, in the post-earthquake restoration exercise, the Turkish Psychological Association (TPA, 1999) began one of the most comprehensive disaster relief mental health services for survivors. They delivered their services from the very beginning and continued for 3 months during the recovery process. They were on constant duty with 500 volunteer counselors and psychologists. According to the TPA (1999) study, 60% of adult survivors developed posttraumatic stress reactions. Their study buttress on recent findings that found a link between earthquake experience and posttraumatic stress reaction. For example, in an investigation of the prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder and the use of coping strategies among adult earthquake survivors in Nepal, findings revealed that earthquake poses significant distress on adult survivors' mental health (Baral and Bhagawati, 2019). However, the study conducted at that time by the Turkish Psychological Association was one of the earliest PTSD studies in Turkey dealing specifically with earthquakes, and generally with stress reactions.

From that study also, officials recorded 505 people being disabled due to physical injuries they experienced in the earthquake. This was however contradictory to civil disability organizations' reports as more than 1,000 people were reported disabled. To them, the number is inconsistent because the disabled survivors were ashamed to appear in public and seek help even though civil organizations and charity foundations were willing to cover the cost of prosthetic arms and legs. But not even a single individual disabled survivor applied or was even willing to receive such cost-free services. In this regard, Durkin and Thiel (1993) opined that a long-term physical rehabilitation process would seem to benefit victims if integrated, and specially designed with mental health programs because of the combination of different emotions as well as physical trauma. Meaning disasters affect attitudes, belief systems, faith, and emotions going forward. Such beliefs, attitudes, and emotions in most instances pertain to faith in public institutions, and social change organizations (Sibley and Bulbulia, 2012).

For children, efforts were also made by an Istanbul-based non-profit organization, the Children Foundation (1999) to extensively study the disaster area in order to suggest a trauma center for children. There were also other studies conducted after the earthquake for the purpose of screening, epidemiology or evaluation, and identification of emotional distress students (Bulut, 2010; Bulut, 2018).

Earthquakes are real and they constitute one of the most dangerous types of natural disasters due to lack of advance warnings and post-disaster difficulties. Therefore, in recent years, some universities and institutions have begun to study earthquake disasters. For example, the University of Delaware Disaster Research Center and the University of New York have a Multidisciplinary Center for Earthquake Engineering Research. Similarly, the University of North Dakota has set up new counseling programs geared toward disaster counseling. The American Red Cross offers disaster training programs for mental health experts and damage assessment and mitigation training programs for citizens. All of these programs indicate a growing interest in studying earthquakes in academic and civic institutions.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Baral IA, Bhagawati KC (2019). Post traumatic stress disorder and coping strategies among adult survivors of earthquake, Nepal. BMC Psychiatry 19(1):1-8.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Ba?o?lu M, Mineka S (1992). The role of uncontrollable and unpredictable stress in posttraumatic stress responses in torture survivors. In Ba?o?lu, M., Editors, Torture and its consequences: current treatment approaches. UK: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

|

|

|

|

|

Baytiyeh H (2014). How can school education impact earthquake risk reduction in Lebanon?. Education, Business and Society: Contemporary Middle Eastern Issues.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Belloc M, Drago F, Galbiati R (2016). Earthquakes, religion, and transition to self-government in Italian cities. Quarterly Journal of Economics 131(4):1875-1926.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bonaiuto M, Alves S (2012). Residential places and neighbourhoods: Toward healthy life, social integration, and reputable residence. In S. Clayton (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Environmental and Conservation Psychology (pp. 221- 247). New York: Oxford University Press.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bonanno GA, Galea S, Bucciarelli A, Vlahov D (2006). Psychological resilience after disaster: New York City in the aftermath of the September 11th terrorist attack. Psychological Science 17(3):181-186.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bulut S (2006). Comparing the earthquake exposed and non-exposed Turkish Children's Posttraumatic stress reactions. Anales de Psicologia 22(1):29-36.

|

|

|

|

|

Bulut S (2010). Children's posttraumatic stress reactions and sub-symptoms: Three years of longitudinal investigation study after a direct exposure to an earthquake and school's collapse. [Depremi direk olarak ya?ayan ve okullar? y?k?lan çocuklarda görülen travma sonras? stres tepkilerinin ve alt boyutlar?n?n üç y?ll?k boylamsal incelenemsi.] Turkish Journal of Psychology 25(66):87-100.

|

|

|

|

|

Bulut S (2018). The role of objective and subjective experiences, direct and media exposure, social and organizational support, and educational and gender effects in the prediction of children posttraumatic stress reaction one year after calamity. Anales de Psicología 34(3):421-429.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bulut S (2021). Üniversite ö?rencilerinin covid 19 pandemisinin do?ru yönetimi konusunda e?itilmesi ve normalle?me sürecine katk?s?n?n sa?lanmas?. Infecious Travma and Post Traumatic Growth in The Time of Covid-19 Pandemics. Pages 67-79. Ibn Haldun University Press.

|

|

|

|

|

Children Foundation (1999). Children Foundation Report. Çocuk Vakf?, Deprem çocuk raporu. ?i?li, Istanbul: Karada?, A.

|

|

|

|

|

Devlet ?statistik Ensitütüsü (DIE) (2001). Turkey's 2000 census data. Turkey, Ankara, Devlet Istatistic Enstitusu. Retrieved March 5, 2001, from:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Durkin ME, Thiel CC Jr. (1993). Earthquakes: A primer for the mental health professions. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality 8(5):379.

|

|

|

|

|

Galea S, Nandi A, Vlahov D (2005). The epidemiology of post-traumatic stress disorder after disasters. Epidemiologic Reviews 27(1):78-91.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Goulet JA, Michel C, Kiureghian AD (2015). Data?driven post?earthquake rapid structural safety assessment. Earthquake Engineering and Structural Dynamics 44(4):549-562.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Guha-Sapir D, Vos F, Below R, Ponserre S (2012). Annual Disaster Statistical Review 2011: The Numbers and Trends. Brussels: CRED.

|

|

|

|

|

Gustafson P (2014). Place attachment in an age of mobility. Place attachment: Advances in Theory, Methods and Applications, pp. 37-48.

|

|

|

|

|

Hallegatte S, Vogt-Schilb A, Bangalore M, Rozenberg J (2017). Climate Change and Development Series: Unbreakable; Building the resilience of the poor in the face of natural disasters. Washington, DC: World Bank. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ireland S (2016). Education disrupted: Disaster impacts on education in the Asia Pacific region in 2015. Tanglin International Centre.

View

|

|

|

|

|

Liu M, Wang L, Shi Z, Zhang Z, Zhang K, Shen J (2011). Mental health problems among children one year after Sichuan earthquake in China: a follow-up study. PloS One 6(2):e14706.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Manandhar S (2016). Living in tents nearly a year after quake: Nepalese Struggle to Endure Winter. Global Press Journal.

View

|

|

|

|

|

McCaughey BG, Hoffman KJ, Llewellyn CH (1994). The human experience of earthquakes: In: R. J. Ursano and McCaughey, B. G., Editors, Individual and community responses to trauma and disaster: the structure of human chaos, Cambridge University Press, New York.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mehregan N, Asgary A, Rezaei R (2012). Effects of the Bam earthquake on employment: a shift?share analysis. Disasters 36(3):420-438.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mitchell J, Holzer T (2000). Geotechnical effects. In C. Scawthorn, (Eds.), Marmara, Turkey earthquake of August 17, 1999: Reconnaissance report (pp. 19-35). New York: The Multidisciplinary Center for Earthquake Engineering Research.

|

|

|

|

|

Roghaei M, Zabihollah A (2014). An efficient and reliable structural health monitoring system for buildings after earthquake. APCBEE Procedia 9:309-316.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Salcioglu E, Ozden S, Ari F (2018). The role of relocation patterns and psychosocial stressors in posttraumatic stress disorder and depression among earthquake survivors. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 206(1):19-26.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sibley CG, Bulbulia J (2012). Faith after an earthquake: A longitudinal study of religion and perceived health before and after the 2011 Christchurch New Zealand earthquake. PloS One 7(12):e49648.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sun M, Chen B, Ren J, Chang T (2010). Natural disaster's impact evaluation of rural households' vulnerability: The case of Wenchuan earthquake. Agriculture and Agricultural Science Procedia 1:52-61.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Tsuchiya N, Nakaya N, Nakamura T, Narita A, Kogure M, Aida J, Tsuji I, Hozawa A, Tomita H (2017). Impact of social capital on psychological distress and interaction with house destruction and displacement after the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 71(1):52-60.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Turkish Psychology Association (TPA) (1999). Turk psikologlar derne?i deprem özel raporu. Retrieved October 30, 2000, from

View

|

|

|

|

|

Webb G (2000). Restoration Activities. In C. Scawthorn, (Eds.), Marmara, Turkey earthquake of August 17, 1999: Reconnaissance report (pp. 109-117). New York: The Multidisciplinary Center for Earthquake Engineering Research.

|

|

|

|

|

Yamamura H, Kaneda K, Mizobata Y (2014). Communication problems after the great East Japan earthquake of 2011. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 8(4):293-296.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Zhang Y, Ho SM (2011). Risk factors of posttraumatic stress disorder among survivors after the Wenchuan earthquake in China. PLoS One 6(7):e22371.

Crossref

|

|