ABSTRACT

Africa embarked on an ambitious and promising free trade area agreement. If applied fully, it can inject a magical potion into the lives of the African economies which currently seem doomed to economic ICU. The agreement is expected to induce intra-continental trade, industrialization, integration all mainly because of free movement of people and goods. Meaning, lowering border controls and checkpoints, but, here the free movement of people and goods can be problematic for the continent. As we all know, the availability of porous borders in the continent is one of the main causes of peace and security challenges of the continent. The article show the dilemma the continent will face to choose between security and economic advancement.

Key words: African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), free movement, porous borders, dilemma.

Regional integrations and regional trade areas are one of the main instruments for fighting poverty and promoting economic development. According to the handbook of the World Bank on Preferential Trade Agreement (PTA) Policies for Development (2011), no low-income country has managed to grow and sustainably reduce poverty without global or regional trade integration. According to the handbook, in the short time, the regional trade will allow countries to expand their market for goods and services contributing to growth then, in the long term, the trade will result in integration contributing to furthered growth through experience, increased productivity and competition.

According to CFI (2021), there are different kinds of regional trade agreements. They range from Preferential Trade Areas which involves reducing trade barriers to full economic integration which is the final level of trading agreements. According to the institute, the free trade area is one type of regional trade agreements which involves the removal of all forms of trade barriers so that goods and services can move freely among themselves, i.e. relaxing border controls.

Borders in Africa are alien in the continent. According to Asiwaju (2015), much of the borders encompassed similar ethnic groups into two or more contrived citizenships, inflicting a huge blow to the social and economic endeavors of these very people. The words of Lord Salisbury describe the situation clearer:

“We have been engaged in drawing lines upon maps where no white man’s foot ever trod; we have been giving away mountains and rivers and lakes to each other, only hindered by the small impediment that we never knew exactly where the mountains and rivers were”(Ibid).

After independence, the continent was divided into two camps regarding the artificially created borders; Revisionists and Anti-revisionists, based on the idea of revising or keeping the borders inherited from colonialists respectively. Only four states rejected the idea of Anti-revisionists. Somalia, Togo and Ghana refused to inherit the alien boundary and forwarded their interests to unify their divided ethnic groups under one political rule. The rest was Morocco; it demanded boundary revision (Ibid).

Nonetheless, the OAU decided to keep the statusquo and continue using the already demarcated boundaries, avoiding conflicts and contestations as the main reasons. But, the results show in contrary; the continent had several border conflicts in almost every region. These conflicts range from the war between Ethiopia and Eritrea on the contested area of Badme in the east, the territorial disputes on the Island of Mbanié between Gabon and Equatorial Guinea in the west, the dispute between Algeria and Morocco (the Sand War) in the north to the tension between Swaziland and South Africa in the southern part.

In addition to the above conflicts, borders in the continent are causes of insecurity because of their porosity. A lot of researches indicate that the borders of Africa are porous; they are ill-controlled. As a result, it is very easy for people to cross into the territory of neighboring state/country and cross back out. The various political and administrative institutions in particular and the states, in general, are weak in a way that their penetration power diminishes as one goes from the center to the periphery (Wairagu, 2004). The borders are so leaky that they are causes of different peace and security challenges; small arms and light weapons circulate highly, human and drug traffickers thrive upon them and various clandestine violent criminal groups find them safe haven. Therefore, it is believed that tightening border controls among other things will be a remedy to curb these social evils.

On the contrary, most of the AU member states are planning to lower border control in the name of trade and free movement of people and trade. In 2018, forty-four African heads of states and governments signed a treaty which establishes the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). It is the biggest free trade agreement since after the establishment of the World Trade Organization and is likely to host 1.2 Billion people and a total of GDP worth more than 2 Trillion Dollars a year. According to Apeh (2018), It has four main objectives:-

1. To create a single market; this will help facilitate the free movement of persons, goods and services, and investments which will help fast-track the creation of African customs union,

2. To reinforce intra-African trade. This will better harmonize the coordination of trade liberalization and facilitation regimes and instruments across the Regional Economic Communities (RECs) and Africa in general,

3. To accelerate regional and continental integration procedures, and resolve multiple and overlapping memberships challenges,

4. To augment industrial competitiveness through production, market access and resource relocation.

As indicated in the first objective of the agreement, it is likely for increased free movement of people and goods across borders to happen. This major phenomenon is clearly a driver of increased trade and economic advancement, but as discussed in the first section of the paper, free movement of people and goods across borders is also problematic. Thus, this article will try to show how the continent is faced with the dilemma of whether to put a stronger border and checkpoints control in place to curb the spread of illicit activities; this will have an adverse effect on the AfCFTA as it puts tough restrictions on the free movement of peoples and goods, or to lower their (states) guards in the name of free movement of people and goods which might compromise their national security.

TRADE (INTRA-CONTINENTAL) IN AFRICA

Schmieg (2016) says Africa has an insignificant share of world trade. It has only 2.4% of the share of the global export, with Sub-Saharan Africa only accounting for just 1.7 %. But, world trade has huge importance for the continent in terms of import as their economy is heavily reliant on it.

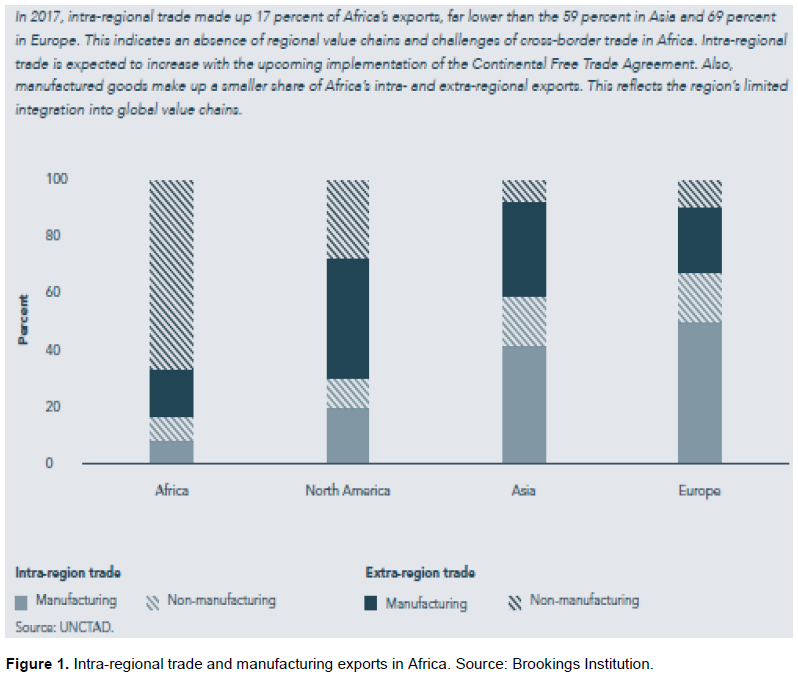

When we look into intra-continental export only in 2017 UNCTAD (ND), the number plummets to 16.6% compared to the 68.1, 59.4, and 55% in Europe, Asia and America, respectively. This is reiterated by Songwe (2019): intra-African exports have increased from about 10% in 1995 to around 17 % in 2017, but it remains low compared to levels in Europe, 69% and Asia, 59%. According to UNCTAD (2019)’s report, the total amount of trade from Africa to the rest of the world averaged US$760 billion from 2015-2017. This is higher compared to Oceania’s $481 billion, Europe’s $4,109 billion and America’s $5,140 billion. This shows how the continent is export-dependent on the rest of the world, not on other African countries.

In terms of intra-continental trade (both import and export among domestically), the numbers are far more unimpressive compared to other continents. Africa had a total of 2% of intra-continental trade between the years 2015-2017 (UNCTAD, 2019). According to the African Development Bank (2017), even though there is a sign of increase, trade within the continent is low. The bank strengthens its argument by indicating the amount of petroleum export and import in the continent. From 2010 up to 2015, Africa exported around US $85 billion worth petroleum to the world, yet the continent imported petroleum worth between US $63 billion to US $84 billion from the rest of the world.

One can observe in Figure 1 by Songwe (2019), how intra-regional trade is low compared to other regions of the world. The figure also shows that the continent is not only lagging behind the rest of the other regions in terms of trade within itself, but also regarding extra-regional trade.

Much of the trade existing in the continent is in the form of informal cross border trade (ICBT). For instance, in the Southern African Development Community (SADC) region ICBT constitutes about 30-40% of trade within the region and 40% in the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) region (Sommer and Nshimbi, 2018). If we take Uganda specifically, more than 86% of its exports are in the form of ICBT in 2006; the same is true for Rwanda as its ICBT was more than 50% higher than formal exports in 2011. Not only is the amount of trade significant, also a large number of vulnerable people are employed in it. In the lack of formal economic prospects (like employment opportunities) and in fragile and conflict-affected states, ICBT comes in and fills the gap by giving desperate people jobs and incomes, especially women and youths (Stuart, 2020). For example, in the West and Central Africa women comprise 60% of the informal traders and in the Southern part of the continent women have a higher share of the ICBT trade; compared to the above regions, they comprise 70% of the informal traders. The UNCTAD (ND) even refers to ICBT as ‘female-intensive sector’ because of the high involvement of women.

AFCFTA AND PROSPECTIVE BENEFITS

AfCFTA is expected to benefit member states by lowering costs for both producers and consumers as it lowers and reduce tariffs and non-tariff barriers. The agreement is also expected to propel the volume of intra-African trade by 81% in 2035, and the amount of total African exports by 29 % (World Bank, 2020).

Other studies and reports also indicate different yet very close figures regarding the intra-trade of the continent as a result of the free trade area. One another advantage of the agreement, according to Songwe (2019), is that when African countries trade with themselves, they exchange more manufactured and processed goods, have more knowledge transfer, and create more value.

As we all know, Africa mainly exports raw materials and agricultural produces. Between the time 1990 and 2014, Africa heavily relied on the income generated from the extractive industry except for Rwanda, Senegal, and Sudan. But, by the successful implementation of the agreement, it is possible for the economies of the continent to diversify their production and export which will enhance productivity and it will also incorporate small and medium-sized enterprises (Ibid).

Another main area where the continental free trade area comes in handy is regarding employment. The continent has a large percentage of unemployed people. For instance, if we look at Eswatini, Botswana, Namibia and South Africa, they have 56, 36, 46 and 54 % rate of unemployment respectively at the national level (Lungu, 2019).

Most of the economies of African countries are dependent on extractive industries producing primary products. These industries, according to Lungu (2019), are capital intensive yet they generate few jobs for the youthful continent in general. But, as discussed earlier, with the coming of the CFTA, production diversification is expected; countries will be able to shift from producing primary products to trade in manufactured products ultimately leading to industrialization. Lungu refers to this shift as a “structural change” that will bring economic growth and better employment opportunities.

According to the World Bank report (2020), agriculture will provide one-quarter of the employment opportunities in the continent by 2035. The figures vary across regions; it is projected that in North Africa it will employ 10.7%, in East Africa 47.8%, in southern Africa 29.8% and West Africa 26.7%.

According to the bank, the second significant employer in the continent by the year 2035 is the wholesale and retail trade sector. The sector is projected to have 21.1% employment across the continent with different figures among countries. The next big employer is the public service sector. The sector includes education, health, electricity, water, and public administration. It is expected to have an employment share of 15.2%. Subsequently, other sectors like recreation and communication take 2.5 and 2.2% of employment respectively.

415 million people live in extreme poverty in 2018; meaning the continent comprises 57 % of the total figure; the situation is severe in Sub-Saharan Africa. The bank also estimated that the rate of poverty is going to decline by 10.9% in 2035 as a result of the distributional effect of the agreement and also the full implementation of the CFTA will allow the continent to lift 30 million people or 1.5 % of the continent’s population out of poverty by the above time. Additionally, the bank also predicted that the free trade area, if applied fully will allow the continent to lift another 67.9 million people out from moderate poverty (the state in which one can survive by meeting the basic need for the minimum standard of well-being but cannot meet the other aspects of life adequately).

There is also going to be an increase in the amount of wage that the average African will receive after the full implementation of the agreement. According to Madden (2020), AfCFTA will boost regional income by $450 billion. There are going to be numerical disparities across regions and individual countries, that is countries and regions with few barriers to trade will tend to benefit more from improved market access. According to the World Bank report (2020), in general, there will be a positive wage change in the continent. If we look at the numbers deeply, for instance, the wage for skilled labor will be higher than that of the unskilled one. If we also look at the figures in terms of sex, female wages would grow faster than that of their male counterparts.

SECURITY AND BORDERS IN AFRICA

As discussed earlier in the introductory section, borders are not homegrown phenomena for Africa, rather they are imposed by colonial masters irrespective of the social, political and economic realities of peoples and societies of the continent. Borders, according to Thomson (2016), are arbitrary in their nature and are the inheritances of colonialism in Africa. To make matters worse, they are not monitored effectively. This idea is supported by Adetiba (2019); Adetiba argues, “Stumpy border control, in addition to corruption and the weak governments' structure, provides a conducive environment for transnational crime syndicates to emerge”.

Borders in the continent are hubs for violent and extreme groups. Islamic State in the Greater Sahel can be taken as an example here. According to Le Roux (2019), in 2018 the group was linked to 26% of all events and 42% of all fatalities and in 2019 more than 570 fatalities, more than any group in the region. The group is operating along the border areas of Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger.

One can also take Boko Haram as an additional example for the above cause. According to Salifu (2020), the group which is based in Nigeria is carrying out attacks in the neighboring countries such as Benin, Cameroon, Chad and Niger, because of the presence of porous borders along with the listed countries.

If we look at the porosity of borders from the lens of illicit Small Arms and Light Weapons (SALW) movement, we can also observe how the borders are posing a real danger to the peace and security of states of the continent. SALW is circulating the continent in huge number. Arms proliferation on the African continent poses a threat to the security of lives and properties. It is estimated that there are 100 million small arms in Africa, especially around the horn of Africa in countries like Somalia, Ethiopia, Southern Sudan the violent belt of Central Africa and many areas of West Africa (McCullum, 2016). But, according to Gramizzi (2014), the number of SALW in the continent is further increased to 150 million and most of them are in the hands of civilians.

We can also take the following figures from Metemaworeda of the Amhara Regional State in north-west Ethiopia, which is a bordering region with the neighboring Sudan. According to the Ethiopian Herald (2016), along with other major areas, the Sudan-Metema-Humera is the major entry point of illicit SALW in Ethiopia (Table 1).

The above figures are fairly large, but according to the woreda Federal Police division, the number is still low compared to the severity of the illicit flow of small arms in the area. the Federal Police division on the area estimates that tens of thousands of firearms and their ammunition make their way into the country through this point,but they are only tracing out a quarter of them.

To make matters worse, these large numbers of SALW are weapons of choice to galvanize existing conflicts across the continent; one can take the conflicts in DRC, Libya and the pastoralist conflicts in the eastern part of the continent as an example.

Additionally, these leaky borders between states of the continent are thriving grounds for organized trans-boundary criminal groups. Especially, the eastern part of Africa is actively used by these groups to smuggle weapons in large number, conduct trafficking in persons, drugs and natural resources. They are carrying out their operations using modern and advanced technologies and are committing organized crimes (UNODOC, 2021). Accordingly, it is evident that the continent’s borders are putting the security of nations and their citizens at stake.

AFCFTA AND SECURITY: DILEMMA

As discussed in the earlier sections of this paper, the continental free trade area will bring an unprecedented economic boost in the continent as a result of increased trade and movement of people. On the other hand, the continent is paying a huge price in different forms because the easiness of borders and checkpoints for people and groups with hidden intentions (ranging from informal traders to organized crime syndicates) to cross-in to other country and cross-out again.

AfCFTA is a double-edged sword which is very capable of striking both ways. As thoroughly discussed, it brings positive economic impact for the continent in a range of ways; starting from employment to industrialization. On the contrary, it can be an issue to reckon with, if states put their guard down and allow them to be engulfed with a scourge of people and goods.

It is almost impossible for any regional economic integration to thrive if people are not entitled to freely move. According to the IOM (n.d.), in West and Central Africa, intra-regional movement of people represents a large part of cross-border movements and has been widely recognized as a driver to the region’s economic growth and stability.However, according to the socio-political realities of the continent, the free movement of people can be a distressing phenomenon. In the same report, IOM indicated that because of the recent regional security challenges, countries in the region are reconsidering their approach regarding migration which can be taken as a movement of people.

The presence of similar ethnic groups in different sovereign administrations and irredentist claims is also another point of dilemma. African borders are arbitrary and after independence Africa’s borders continued to be feeble. Moreover, they became causes of social insecurity and irredentism. It has been almost impossible to have viable stability and long-term peace and security within and between many African states and the porous African borders have resulted in the regionalisation of conflicts, resulting in chaos in areas such as the Mano River in West Africa, the Great Lakes region and the Horn of Africa (Nguendi, 2012). One can take the Ogaden war between Ethiopia and Somalia and the Western Sahara conflict as examples. This major phenomenon will have a decisive effect in the success of the agreement

On the contrary, this situation can be an advantage in facilitating trade. As people speak and understand the language and traditions of people living at the other side, it will allow them to interact easily and be engaged in trade and other economic activities, which ultimately will result in increased personal, national and continental economic gains and benefits. Moreover, it can be the much needed crucial cornerstone to a politically integrated Africa.

The continent came up with the long-awaited agreement to establish one of the biggest free-trade regions in the world. The agreement is going to thrust the continents’ economy into a more integrated and sophisticated one as it increases employment opportunities, lowers trade and commodity costs and advances industrialization or specialization and mainly the free movement of people and goods will be the main character of the agreement.

Against this backdrop, the continent is infamous for the prevalence of different types of conflicts and problems; among the many, the presence of porous borders is responsible for being fertile ground for the mushrooming of various organized crime syndicates and extreme groups. Besides, borders in Africa are mainly used for illegal cross border trading activities, illicit smuggling of weapons and human trafficking activities. Thus, AfCFTA might be used by these groups for their own advantages compromising the already weak and fragile peace and security of the continent.

Hence, the continent is faced with a situation that can have a detrimental effect on its development aspirations on one hand and on its peace and security, on the other hand.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Adetiba T (2019). Transnational Syndicates and Cross-border Transfer of Small Arms and Light Weapons in West Africa: A Threat to Regional Security. Journal of African Union Studies 8(1):93-113.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

African Development Bank (2017). Intra-African trade is key to sustainable development - African Economic Outlook.

View

|

|

|

|

|

Apeh C (2018). The AfCFTA Objectives, Concerns and Opportunities. Africa Center for International Trade and Development (ACINTAD).

View

|

|

|

|

|

Asiwaju A (2015). Borders in Africa; an Anthology of the Policy History. Institute for Peace and Security Studies, pp. 255-261.

|

|

|

|

|

CFI (2021). Regional Trading Agreements.

View

|

|

|

|

|

Gramizzi C (2014). Tackling Illicit Small Arms and Light Weapons (SALW) and Ammunition in the Great Lakes and Horn of Africa. Africa Peace Forum, China Arms Control and Disarmament Association and Safer World, pp. 6-7.

|

|

|

|

|

IOM (n.d.). Immigration and Border Management.

View

|

|

|

|

|

Le Roux P (2019). Exploiting Borders in the Sahel: The Islamic State in the Greater Sahara, Africa Center for Strategic Studies.

View

|

|

|

|

|

Lungu I (2019). A Fresh Chance for Africa's Youth, Labour Market Effects of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). GIZ-AU Briefing Paper. Econstore pp. 1-3.

|

|

|

|

|

Madden P (2020). AFRICA IN FOCUS Figure of the week: The AfCFTA's effects on trade and wages in Africa. Brookings institution.

View

|

|

|

|

|

McCullum H (2016). Small arms: the world's favourite weapons of mass destruction, Africa Files 5:2-5.

|

|

|

|

|

Nguendi F (2012). Africa's international borders as potential sources of conflict and future threats to peace and security. Institute for Security Studies (ISS) 233:1-11.

|

|

|

|

|

Salifu U (2020). Border porosity and Boko Haram as a regional threat. Institute for Security Studies (ISS).

View

|

|

|

|

|

Schmieg E (2016). Global Trade and African Countries Free Trade Agreements, WTO and Regional Integration. German Institute for International and Security Affairs.

View

|

|

|

|

|

Sommer L, Nshimbi C (2018). The African Continental Free Trade Area: An Opportunity for Informal Cross-Border Trade, (Crosby A, ED.). Bridges Africa 7(4):7-10.

|

|

|

|

|

Songwe V (2019). Intra-African trade: A path to economic diversification and inclusion. Brookings Institution.

View

|

|

|

|

|

Stuart J (2020). Informal Cross Border Trade in Africa in a Time of Pandemic. Trade Law Centre (TRALAC).

View

|

|

|

|

|

The Ethiopian Herald (2016). Ethiopia: Government Set to Control Illicit Arms Possession. All Africa.

View

|

|

|

|

|

UNCTAD (2019). Economic Development in Africa Report 2019: Made in Africa: Rules of origin for enhanced intra-African trade. UNCTAD. UNCTAD/ALDC/AFRICA/2019/Corr 1:13-48.

|

|

|

|

|

UNCTAD (ND). Informal cross-border trade for empowerment of women, economic development and regional integration in Eastern and Southern Africa. UNCTAD.

View

|

|

|

|

|

UNODOC (2021). Transnational Organized Crime in Eastern Africa. UNODOC.

View

|

|

|

|

|

Wairagu F (2004), The Proliferation of Small Arms and Their Role in the Escalating Conflicts in East Africa, In Nhema A. (Ed), The Quest for Peace in Africa; Transformations, Democracy and Public Policy, OSSREA, Addis Ababa.

|

|

|

|

|

World Bank (2020). THE AFRICAN CONTINENTAL FREE TRADE AREA: Economic and Distributional Effects. The World Bank Group. DOI: 10.1596/978-1-4648-1559-1

Crossref

|

|