The study investigated police officers’ perceptions about corruption in Zimbabwe. The study was informed by Bourdieu’s theory of habitus. A case study design involving a self-administered questionnaire was used to collect data from sixty-four respondents sampled using a census method of sampling. Data was analysed using descriptive statistics and presented on tables and pie charts. The study revealed that police officers were aware of corruption through training, discussions, presentations by bosses and literature. Police officers do not continue to learn about corruption through formal means like workshops. They perceived that corruption existed in the police force; believed that police corruption was due to low salaries, poor working conditions and greediness. Police officers perceived that the existence of corruption in society was due to low salaries, long time in positions of authority and greediness. They also said that corrupt people were usually the rich, the middle class, company owners, top politicians or top management. The factors contributing to corruption in the police force are not due to lack of awareness but relate to power, conditions of service or selfish behaviour or interests. It is recommended that the government improves conditions of service for police officers to reduce corruption.

The problem of defining corruption has been noted by many authors (Yerevan, 2000). This is because corruption is found in different forms and hence not easy to find one definition that encompasses various types. But many authors (Yerevan, 2000; Myint, 2000; Frisch, 1996) seem to agree on the definition given by Palmier (1983) that corruption is the use of public office for private advantage or private gain or private ends. The key to this definition is the position a person has. This is because for a person to be corrupt, someone there is an element of one having a certain position which give her or him a certain advantage or privilege. This is shown by Oxford Dictionary definition which says corruption is dishonest or illegal behaviour especially of people in authority.

The concept of corruption has been a point of intrigue since ancient times. For example, Plato’s theory of perverted constitutions describes how different types of government are not guided by law but by their own interests. In modern times, ideas on corruption have further been conceptualised by Machiavelli, Montesquieu and Rousseau. For Machiavelli, corruption is a process by which the virtue of the citizen is undermined and eventually destroyed. Montesquieu regarded corruption as the dysfunctional process by which a good political order is perverted into an evil one and a monarchy into despotism. Similarly, Rousseau sees political corruption as a consequence of the struggle for power. This is further supported by the famous words of both Rousseau and Acton who say ‘all powers tend to corrupt and absolute power corrupts completely.’ Fredrich comes in with the idea that corruption is a kind of behaviour which deviates from the norm actually prevalent or behaved to prevail in a given context such as the political. He goes on to say corruption constitutes a break of law or of standards of high moral conduct (Yerevan, 2000). So if police officers are allegedly involved in corruption it means they are deviating from the duties they are supposed to guard against. It is therefore important for police officers to be aware of corruption and hence the need for this study to find out the extent of this awareness.

Theoretical framework

The study is guided by Bourdieu’s theory of habitus with its related concepts of field and capital. Bourdieu (1990:53) defines habitus as “a system of durable, transposable dispositions, structured structures predisposed to function as structuring structures….” Maton (2008:12), taking a cue from Bourdieu’s definition, says habitus is “property of actors that comprises a structured and a structuring structure.” Nicolaescu and Contemire (2010:14) adds in their own definition of habitus, “a system of dispositions that generate practice and perceptions, a normal or typical, state of appearance of the body.” From the three definitions, it can be deduced that habitus is like a person’s character from which he/she draws his/her way of acting or bases practices. Bourdieu used the theory of habitus to explain the action of human beings. He said that human action is strategic and practical to that person without referring to it as being subjective or objective. Thus Lizardo (2012:3) argues that habitus is a way to explain social action. Swartz (2002:655) adds that habitus leads to practices of a particular manner of style. Thus the theory of habitus can be used to explain why police officers are allegedly corrupt. Ngarachu (2014:59) says habitus is based on our experience. Pickel (2005:20) adds that habitus is related to power which is an important factor on the problem of corruption.

Power is related to the amount of capital a person has (Beames and Telford, 2013). Bourdieu identified four capitals namely economic, social, cultural and symbolic which are found in any particular field where individuals interact and are involved in various activities. The fields can be social, economic or political (Gennrich, 2015). For example, education/schools are particular examples of social fields. The government and its agencies like the army and police are examples of political fields. Swartz (2002) says that fields are known for production, exchange of goods and services, competition and struggle for power and resources. When various fields interact with each other they do so in terms of the capital they possess. Those with more capital tend to have more influence (Bearnes and Telford, 2013). When fields interact with each other, they do so on the basis of hierarchy and struggle (Mangez and Hilgers, 2012). A typical example of such interaction is that of the police, with the power derived from being officers of the government, and public transporters with the economic power they have.

Literature

Research studies on corruption have not been easy to get especially ones that are on Zimbabwe. A report by Anti-Corruption Trust of Southern Africa (2010) showed that Zimbabwean traffic police are more corrupt than those in Botswana and Namibia. The report goes on to say drivers prefer paying bribes to avoid prescribed traffic fines which are more than what they pay to police officers. A report by the Anti-Corruption Trust further shows that bus operators were losing a lot of money to police officers through bribes. Owners of bus companies who attribute the bribery problem to poor salaries paid to civil servants. The aim of this study was to find out from the police officers themselves what they have to say about corruption.

The importance of training was noted by a police officer-in charge of the Rwandan National Police who said training helped to raise awareness about corruption in the force, win confidence of population, fight corruption, cleanse the heart of police of any corrupt tendencies and equip them with ways to fight corruption (Allafrica.com). Similarly, Henriot (2007) also suggests that the values and norms of anti-corruption can be taught in educational institutions as a way of fighting corruption in the same way that HIV and AIDS awareness has been promoted in educational institutions. The aim of this study was to find out whether police officers in Zimbabwe are trained about corruption for awareness purposes.

A study by Anti-Corruption Network (2006) in Tajikistan revealed that there was corruption within the police as some were involved in extortion of money or petrol on roads and inspection of business. In Mozambique, a report by USAID (2005) shows that bribes were used to pass roadblocks. This study in Zimbabwe aims to find whether this is also true by asking the police about the existence of corruption.

Ibrahim (2003) points out that corruption is widespread in Nigeria as indicated by the country being ranked in the top two worst corrupt countries in the Transparency International index. This is aggravated by the fact that state agents who were supposed to fight crime, like the police, were also involved in corrupt activities. Sometimes, they even connived with criminal gangs in corrupt activities. This study intends to find the extent of corruption as seen by the police themselves.

Research questions

a) How do police officers learn about corruption?

b) What are the perceptions of the police officers about corruption in the police force?

c) What are the perceptions of police officers about corruption in the Zimbabwean society?

Study site

The study was carried out at a University in Bindura town, the provincial capital of Mashonaland Central. It is to the north-east of Harare and about ninety kilometres from the capital. The original mandate of the university was to train science teachers but it has now diversified to include other disciplines such as commercial, agriculture and social sciences. The department that houses police studies falls under Faculty of Commerce.

Population and sample

The target population were all undergraduate police students in the first, second and third year of training. The students had basic police training for six months who were now enrolled as undergraduate students. After training for Diploma programme, the students worked before enrolling for a degree programme. The total number of the police officers was 75. All were included in the study so the target population became the sample of the study. Of the 75 respondents, five did not want to take part in the study. All the 70 questionnaires distributed were returned. Of the 70 respondents who responded, six were not usable because they did not answer most questions. The actual sample used was 64 which was about 85% of the original targeted population.

Instruments

A questionnaire was used to collect data. The questionnaire was made after reading a number of papers on the topic of corruption. The papers that were of particular importance in designing the questionnaire were research papers by Kerevan and Expert Panel Survey in South Africa. The questionnaire had five sections namely bio data, training, existence of corruption in the police force, existence of corruption in society and police opinions about corruption. Most of the questions were closed type in which respondents were asked to choose from a given choice of answers. The last question asked respondents to give any comment about police corruption in the country. The data was summarised and analysed using descriptive statistics. Data was presented on tables and pie-charts.

Background of respondents

The majority of respondents 56(88%) were males which is an indication that the police force is mainly dominated by males. The views on corruption expressed in this research were mainly from male respondents.

Most of them 42(66%) were in the 26-35 age range which shows that police force is mainly populated by officers in the youth stage.

Twenty-eight (44%) have been in the police force for between 6 to 10 years. Twenty (30%) have been in the police for over 10 years. 14(22%) have been police officers for between 1 to 5 years. These figures indicate that the respondents were made up of officers with varied experiences and hence likely to have necessary experiences about corruption at the workplace.

The majority of police officers (78%) work in urban areas with the least (2%) working in farming areas. This is an indication that respondents were mainly from urban centres where corruption is more likely to take place so will provide valuable data on this.

Respondents originate from different provinces in the country but were mainly from four provinces namely Midlands 15(23%), Masvingo 13(20%), Manicaland 7(11%) and Mashonaland East 8(13%). Respondents were from many provinces in the country so their views about corruption indicate ideas from officers originating from different parts of the country.

The respondents work in various provinces with most of them in Harare 26(41%) followed by those from Midlands 7(11%) and Bulawayo 5(8%). Only 4(6%) of the respondents work in Mashonaland Central, the province where the university is situated. Officers who participated in the research work in different provinces in the country so likely to provide varied experiences about corruption.

Learning about corruption

The fight against corruption includes would-be police officers being trained about the problem of corruption. This was pointed out by Chene (2015) who said that police officers should be equipped with skills to perform their duties with integrity and professionalism. In order to find out if respondents were aware of corruption through learning, they were asked if they learnt about corruption, topics covered and if corruption is also covered at the workplace.

Learning about corruption during training

Respondents were asked whether they had learned about corruption during their police training. Most of the police officers 52(81%) said they had while 9(14%) said they did not (Figure 1).

Coverage of topics

Respondents were given a number of possible topics which may be covered on the topic of corruption and asked whether they covered all or not. On coverage of topics, most 42(66%) said they covered all topics identified, while only 6(9%) said they did not learn any topic on corruption (Figure 2).

Learning about corruption at the workplace

Respondents were asked about learning corruption at the places they worked in terms of workshops, literature, further training, boss talk and discussing with colleagues (Table 1). The results indicate that respondents mainly learn about corruption by discussing with colleagues 49(77%), talking with bosses 48(75%) and literature 43(67%). But there is very little in terms of workshops 21(33%).

The results above revealed that police officers learn about corruption when they are being trained. This is important as corruption is a vice they have to deal with as part of their duties. This is critical as police officers so that understanding of corruption becomes part of their professional socialisation. Even after qualifying, it appears police officers continue to learn about corruption mainly from others and further training but what is disturbing is that there is little learning using workshops for the majority of respondents. Workshops are important as they assist as prevention programmes by involving stakeholders in the fight against corruption (Langseth, 1999). Other studies (Henriot, 2007) have also shown that learning about corruption is necessary for police officers as it assists them to understand the values and norms of fighting corruption. This was also noted by Allafrica.com (2011) who said that the police force in Rwanda are trained about corruption in order to raise awareness and help fight corruption.

Learning about corruption as done by the police officers is in line with the concepts of habitus and field as theorised by Bourdieu. Warwick et al (2017) argues that the interaction between habitus and field is aided by processes of action learning that forms a social friction which assists learning to take place. This means police officers’ secondary socialisation includes learning about corruption which is critical in the government’s fight against corruption.

Existence of corruption in the police force

Chene (2015) says that police corruption exists in various forms such as street-level corruption and bureaucratic corruption. Street-level corruption occurs when police and citizens interact leading to police using their power to get money or sexual favours from the public in exchange for not reporting illegal activities. Bureaucratic corruption refers to the misuse of internal and bureaucratic processes and resources for private gain. In order to find out if police officers were aware of corruption in the police force, respondents were asked if corruption existed in the police force, causes of corruption in the police force, which police officers were more likely to be corrupt, corruption at road blocks and police’s fight against corruption.

Existence of corruption in the police force

Respondents were asked about the existence of corruption in the police force with most of them 49(77%) saying corruption exists in the police force (Figure 3). Only 2% said there was no corruption in the police force. The others said it was difficult to say or gave no answer.

Causes of corruption in the police force

From a given list of possible causes for corruption in the police force, respondents were asked to identify the three they regarded as important. They cited three main reasons for police corruption: low salaries 54(84%), poor working conditions 40(63%) and greed 38(59%) (Table 2).

Corrupt officers

As regards identifying the rank of officers most likely to be corrupt in the police force, respondents said there was no particular rank that can be said to be corrupt 37(58%). Some said it was an individual affair 10(15%) (Figure 4).

Police fight against corruption

On whether the police force is doing enough to fight corruption in the country, 40(63%) said not enough was being done (Figure 5). Only 14% said the police was doing enough to fight corruption.

Corruption at roadblocks

When asked about the existence of corruption at some police roadblocks most respondents 50(78%) agreed that it was practised (Figure 6). Road blocks are common on major roads in Zimbabwe and respondents were asked on reasons for these.

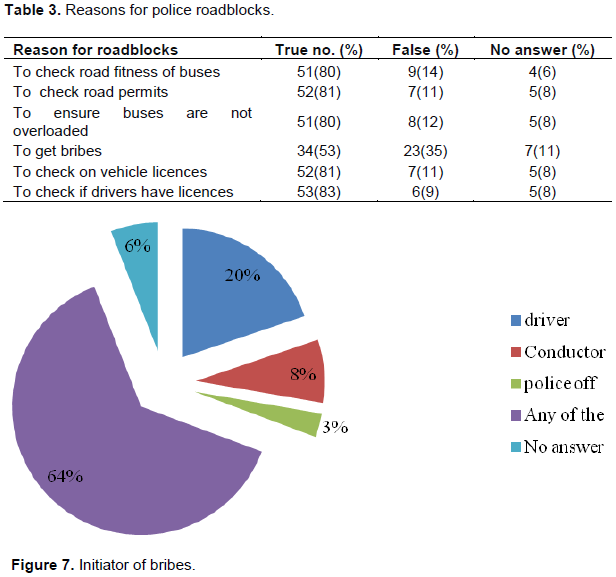

Reasons for police road blocks

When requested to identify any three reasons for police road blocks in the country, respondents identified one that relate to fitness 51(80%), permit 52(81%), passenger capacity 51(80%) and licences 53(83%). Just over half 34(53%) of the respondents believed that police officers hoped to get bribes (Table 3).

Initiator of bribes at roadblocks

On who initiates the idea of bribery at road blocks, most of the respondents 41(64%) said it was any of the three: the driver, conductor or the police officer (Figure 7).

The study has also revealed that they were aware of the existence of corruption in the police force as already noted by the Anti-Corruption Network (2006) who identified the police as one of the sectors prone to corruption in Tajikistan. Similarly, surveys cited by Newham (2002) in South Africa show that police corruption existed. It went on to assert that approaches to corruption have now shifted from finding out whether police corruption existed to finding out about the ‘size, nature and impact of the problem.’ Furthermore, this study has revealed that corruption in police force is a result of low salaries, poor working conditions and greed. A similar observation was made by Spector et al. (2005) about corruption in Mozambique where low pay and poor working conditions make low level officials more likely to participate in corruption. But if these are the main factors for corruption then it would mean the lowly paid officers would dominate in corruption. Yet this study has revealed that police officers believed every rank in the police force is involved in corrupt activities. A study by Porter and Warrender (2009) shows that both low and high ranked officers are involved in corrupt activities, which perhaps explains why studies in most countries show that corruption, is rampant in the police force. For example, Flanary and Watt (1999) show that the police in Uganda is corrupt despite being an institution expected to fight the vice. Similarly, in Ghana (Fijnaut and Huberts (2002), the police is perceived to be one of the most corrupt institution. The difference between this study and the two studies quoted is that police see themselves as being corrupt while in the other studies they are seen by others as corrupt. The evidence therefore corroborates each other. So why do the police continue to be corrupt despite their knowledge about corruption and continued complaints by the public. The answer perhaps lies with what Jain (2001) calls determinants of corruption: “...someone must have discretionary powers... to design regulations as well as to administer them; ... existence of economic rents which can be captured by an identifiable group and a (weak) legal/judicial system which gives low probability for detection for wrong doing.” The importance of power is further supported by Rousseau and Acton (Yerevan, 2000) who say that power has a tendency to make people corrupt.

The existence of corruption in the police force shows the importance of power. The police officers whether rich or poor have political power conferred on them by the duties they do. This scenario is explained by Mangez and Hilgers (2012) who used Bourdieu’s analytical tool of the field when they said other social fields are subordinate to the field of power. When the police who have power based on government positions interact with other people from other fields, they use their power to induce people to be corrupt for their own benefit. In Zimbabwe, this is exacerbated by the fact that police officers earn low salaries so when they interact with other individuals with more capital they are likely to induce them to be corrupt in order to benefit from them. A good example of such corruption occurs at roadblocks as shown below.

Most police officers said there was corruption that occurs at roadblocks where the act was initiated by the driver, conductor or the police officers. The result is similar to what was said by Thabani (2017) that bribes are common in Zimbabwe. This is an example of personal gain corruption (Porter and Warrender, 2009). The police officers want to benefit capital from those involved in the transport sector while drivers want to avoid paying more in fines to government coffers or alternatively being taken to court for violating rules of the road. The police are using the power they have for their own benefit, and is an indication that when two fields (police and transport) interact, struggle occurs as each tries to benefit. In this case although both sides appear to benefit, the police officers benefit more as they lose nothing materially while the drivers or conductors representing bus owners lose money in the process. The gain of the transporter and the workers is being let free and they do not face the justice system at the courts.

Existence of corruption in the Zimbabwean society

Respondents were asked if they were aware of corruption in the Zimbabwean society. The majority of respondents 61(95%) said there was corruption in society (Figure 8).

Level of corruption in society

On how many were corrupt, 47(73%) said many people were corrupt (Figure 9).

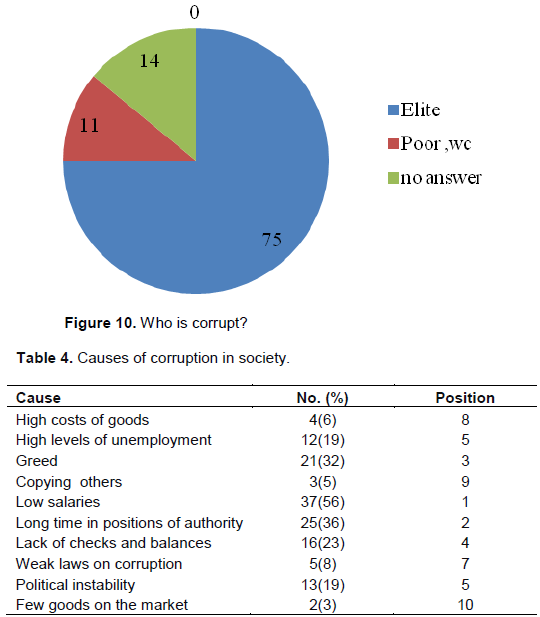

Who is corrupt in society?

Respondents were asked who they thought was most likely to be corrupt in society. On groups or classes of people who are likely to be corrupt, 48(75%) of the respondents identified the rich middle class, company owners, top politicians and top management. Only 7(11%) said poor and working class are also corrupt (Figure 10).

Causes of corruption in society

From a list of given factors for corruption, respondents were asked to identify three which they thought were most important. The three factors mostly identified were: low salaries (56%),

long time in positions of authority 23(36%) and greed 20(32%) (Table 4).

The majority of police officers were aware that corruption existed in the Zimbabwean society. This police perception about corruption in Zimbabwe is confirmed by The International Bank of Reconstruction and Development (2006) which regards Zimbabwe as a country that has gone down on almost every dimension of governance including corruption. The police officers said people most likely to be corrupt were the rich, middle class, company owners and top management.

This finding is corroborated by Gupta et al. (2000) cited by Jain (2001) who say corruption is associated with higher income inequality and by Jain (2001) who asserts that corruption favours the rich. However, Gupta et al. (2000) study also established that there was an association between corruption and poverty. Thus the results suggest that the tendency to be corrupt exist in all classes although it may be more widespread among the privileged classes because of the positions they occupy and the power associated with the positions. This is explained by Bourdieu’s idea of a field which says that “within a field, individuals hold unequal positions and experience unequal trajectories based upon the volume and composition of their portfolio of capital.” (Wacquant, cited in Pather and Chetty, 2015: 59). So when the poor and rich interact, the powerful dominate and take advantage in order to benefit.

The police officers believed that there was corruption in Zimbabwean society because of low salaries, being in positions of authority for long and greediness. These results are similar to results of an Expert Panel Survey (2001) in South Africa which show that some of the main causes of corruption also include greed and desire for self-enrichment and socio-economic conditions. But the main one identified by most respondents was decline in morals and ethics which was not shown by police officers in this study.