The objective of this article is to analyze the restructuring of the craftwork in Brazil from the political and economic conditions in the globalization of capital. As methodology, the analysis of vertical and horizontal integration of artisanal work into the economic and political structure of the country is used in the period of institutionalization and restructuring, as a reference of the transformations from Fordism to post-Fordism mode of development. The main findings include the importance of the analysis of vertical integration in the transformation of occupations and techniques, leading to a major rupture in an economy in the process of industrialization in the last century in relation to cultural characteristics and local folk traditions. The participation of women in the micro-entrepreneurial economy is significant for the strengthening of the artisanal sector today. Due to the differences in the promotion of microenterprises and the patrimonial protection of the culture, the policy on the artisan is strongly fragmented by local or regional proposals.

On April 22, 2015, several civil and governmental agents met to discuss the state of public policies of the artisanal sector in Brazil at the public hearing of the Senate Federal Commission on Education, Culture and Sport (CECE-SF, 2015).

Cultural, labor, business and alternative economic proposals presented a conflictual relationship that sought to regulate the activity in the country, following as a basis the debate on the bill 7755 of 2010 on the professionalization of the artisan (Cavalcanti, 2010).

The bill was approved by the Chamber on September 9, 2015 and institutionalized with Law 13,180 of October 22, 2015, which "provides for the profession of craftsman and other measures" (Brasil, 2015). It can be seen from this that the consolidation of the Law occurred under the diversity of proposals, interests and subjects, as a result of a complex historical process; where the socioeconomic and political transformations requires a structural analysis.

So, why are there different ways of conceiving craftwork in relation to its economic, political and cultural determination? How can this kind of work be understood in the globalization of capital? What structural changes have the artisanal activity in the economic and political situation in Brazil?

Conceptualization of craftwork

Contrary to theories with a cultural focus (Malo, 2002) and pragmatism focus (Senett, 2008) on the artisan, the Marxist theory on craftwork can be developed in order to understand the dynamic movement of this particular work in relation to the whole social work, understanding its transformations and contradictions in a historical period specific.

In this study, craftwork is understood as a form of social work, that is, an activity of the public sphere, socially remunerated and determined by its utility in a specific social context (Gorz, 1991). It can be analyzed from the type of political and economic relation. The categorization of a "craft sector" is designer to each country's economic policies, defining and limiting specific trades and occupations.

Thus, the international conceptualization of craftwork by occupations cannot be confused with the political construction of the artisanal sector by each state or nation. As part of the working class, it can be categorized into three forms or moments in its social relation of exchange of products and services (Marx, 1980): As self-employed activity (by income) in two moments; and as employees (by salary) and employers in a fourth moment.

First: As a form of production of goods with social utility -symbolic or material- within the simple circulation, of direct purchase and sale in a local market place, where the means of production are owned by the producer. It has specific skills (know-how) for the manual use, with simple tools or machinery, and a production planning and management process transforms the material into a product for the consumption of others (whether for subsistence or luxury).

Second: As a form of transition to capitalist production, where the product enters the market, independent of the relation of the producer and the consumer, circulating as a commodity and its relation with capitalist production can present itself as an autonomous work with surplus labor, allowing the valorization and appropriation by the same producer or artisan.

Third: A capitalist form, where wage labor and capital is present within a historical process of production. In this sense, the capacity of work (skills or know-how) is sold to the employer who owns the means of production (fixed capital), the employee subordinates working time to the employer in a contractual way, which allows a valorization of capital and the profit generation.

The significance of craftwork in each country is part of the struggle to define objective conditions such as quantity and quality of crafts, productivity, number of producers, qualities of products and services, production territory, position in the social division of work, and the subjective conditions -identity and identification- of artisans, their recognition as crafts, and the real-imaginary value that has the object and that are concretized as a form of governmental power in the institutionalization. In this way, there can be structural transformation insofar as it is not only part of the local or group identity, but it is also part of a social relation in a system of communication, signification and production.

In order to understand the form of institutionalization of craftwork in the Marxist theory, it is necessary to recognize two forms of integration and formalization of artisanal occupations in the social division of labor (taking into account the concepts of direct and indirect subordination): vertical and horizontal integration (Marx, 2013; Mandel, 1982).

Vertical integration is related to manual production and service capacities within systems of higher population concentration that present demand for skilled workers in trades of transformation and repair, with dependence on the industrial and technological sector; presents an academic structure, which offers its homologation as technical knowledge. Thus, it is craftwork taking into account that one acquires dominance over tools and simple machinery, and where the individual's work is relatively autonomous, either in his or her position as an employee or self-employment. This form of integration is more vulnerable to technological changes and the needs of the population, the mismatches between supply and demand in the labor market, the wage fall, and the creation and destruction cycles of jobs in the market economy.

On the other hand, horizontal integration is related to manual production capacities and services within systems of lower population concentration that seek the symbolic and cultural recognition of occupations in function of their territorial dependence. It is a craft work because it promotes formal and informal learning techniques, where the producer's abilities are evaluated in relation to values, traditions and narratives that do not compete directly in quality with other occupations of industrial and technological sectors.

In this way, the construction of a national discourse and the regional narratives allows the production of the identities of "artisan" (artesão) and "handicraft" (artesanato). Thus, unlike vertical integration, there is a concern here for the conservation of cultural expressions and techniques that seek to define diverse forms of life that refers to nation (or ethnic tradition).

This separation of two forms of relation, antagonistic and complementary, is part of the dynamics of recognition of craftwork and its difficult conceptualization, because it attempts to place at the beginning of the analysis contradictory social phenomena, with activities that fluctuate between formality and informality, between vulnerability and the labor market in capital, between the objectives of cultural preservation and technological transformation. The separation of forms of integration from the artisanal to the hierarchical division of labor builds the basis of the economic and symbolic distinction of the craft occupations in the institutionalization of activity in the last century.

Craftwork and globalization

The conditions of artisanal labor are part of the dynamics of the capitalist mode of production and their limits and contradictions. Although their relationship is more complex depend on the degree of autonomy and their position in relation to the circulation and reproduction of capital. The globalization of capital presents itself in different economic and political changes.

Organizational change of industrial capitalist corporations; which allows a great flow of goods and services in a common financial pattern, driven by international institutions in interaction with States (Alves, 1999). Spatial changes, with the geographical displacement of capital that produces a flexible accumulation and mobilizes the contradiction of capital in time-space, generating new processes of access-exclusion of the population.

Work changes with new forms of control of the relations of production (post-Fordist) thanks to technological changes that subordinate the time and subjectivity of the worker, with precariousness of the labor activity, and that allow to maintain the structural unemployment, and to say a new hierarchical division of work (Antunes, 2005). Changes within sectors or economic activities, producing the transformation of products and services in the competence between the same sectors or, in search of increased profit, move to new sectors or production lines with less competition in the market.

The process of globalization of capital constitutes a part of the economic and political transition from a society based on the Fordism to a post-Fordism (Toyotism) mode of development (Silver, 2005), which does not mean that it is only a step from an industrial society to a Postindustrial; In addition, there are changes in the subordination of non-capitalist production, changes in the centralization of power, in the accumulation of capital and in the exploitation of labor (Antunes, 2002; Sotelo, 2003; Alves, 2008). For this reason, craftwork in the globalization can be understood from this transformation as a transition from a first process of institutionalization in a Fordism mode of development to a restructuring carried out in the post-Fordism mode of development (Martins, 2009).

Changes of work in the globalization of capital have an impact on the organization of production and development (Castells, 2004), generating spaces of vulnerability and inequality of the population, their capacities and ways of life (Castel, 1998), encouraging and strengthening occupations with greater volatility, flexibility and labor dispersion (Standing, 2011), which stimulates the growth of public policies on the population that moves through jobs such as craftwork in recent years. The law on the artisan profession in Brazil is part of the worldwide dynamics of regulation of this form of work in the change of capital. The purpose of this article is to analyze the restructuring of craftwork in Brazil from its political and economic conditions in the globalization of capital; the study is done from historical and structural understanding.

Institutionalization of craftwork in industrial society

Vertical integration

Artisan work in the twentieth century derives from the historical understanding of two forms of production in the previous century. The first, with the trades and productive activities in the great metropolis, with guilds and other corporations until the principles of the Empire when they were extinguished by the interruption of economic liberalism, these being the most recognized forms of sociability in the West with the formation of labor in the colony, who had relevance status and social power (Martins, 2007). The second, in the subsistence economy, or domestic work, with production within large farms and other rural populations, where crafts reproduce daily life forms, the relation between labor and subsistence materializes the reproduction of labor techniques, but has a different status to the city workers (Furtado, 1963).

By the end of the nineteenth century the submission of the enslaved and free laborer changed to the contractual relationship after the abolition of slavery, which meant another form of exploitation in the liberal market (Hunold, 1998). With the consolidation of wage labor on the farms in the nineteenth century, the rural labor force was the main sector of the emerging Republic; regional markets were formed with the inclusion of European immigrant labor and the exclusion of labor from the Afro-descendant population.

The lack of integration between freedmen and immigrants and the absence of capital for investment in the internal market, has strengthened social inequality and the growth of a subsistence economy, outside modernization processes (Costa, 2005). With the emergence of labor instability and the lack of recognition of the free populations, their opportunities and their interests, a new panorama of work appears in the past century. Thus, conceptions of work were more focused on the segmentation of regions and the weak development of the State in national regulation. It is up to the Getúlio Vargas government where political intervention transcends regional interests, promoting a strong process of industrialization by import substitution, especially in the southeast and south from the country. The corporatist labor formation allowed the programming of urban social policies that curbed the problems and inequalities in labor recruitment after the thirties, as well as the recognition of labor rights (Lessa, 2012).

In the middle of the twentieth century, the main problems were the growth of labor informality and unplanned urban growth. The changes of the G. Vargas government were significant for the strengthening of the country's industrialization, which allowed the formation of skilled labor with labor apprenticeship programs in the so-called "S" system (Pochmann, 2006).

Blue-collar workers, technical and service workers inside and outside factories were recognized as opposed to white-collar workers, or non-manual workers in administration, in the division of industrial labor. Thus, the problem of industrialization was the formalization of the social and technical distinction, which defines not only the exclusion of rights, but the distinction of non-industrial forms of production, which is not part of modernization. The importance of the technical integration of craftwork can be understood in a macrostructural aspect as a response to the decline of the rural population and its corresponding decrease in agricultural activity, and the increase of the industrial sector and services (IBGE, 1976).

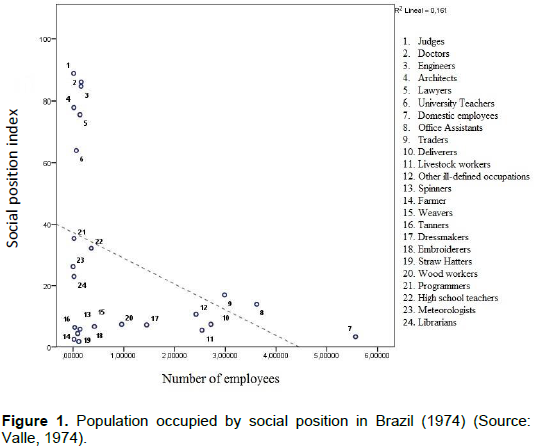

In this way, inequalities in the occupational structure appear, taking into account the indicator of social position by the characteristics of schooling, income and productivity (Valle, 1974), there is a pyramidal form of a smaller number of occupations with a high social position, an greater quantity of workers in occupations with low social status, and that the occupations of craftwork have low social status and low numbers of workers in these activities (Figure 1).

Thus, the probability of reproduction in the industrial society of craftwork tends to occupy low social positions and low numbers of workers, being activities that are easily replaced by the mode of industrial development, their promotion and protection appear limited to the needs of the market and fluctuations in the country's internal economy.

Horizontal integration

On the other hand, the organization of work required to the State to build ideologically an only nation to define a process of integration and control of the subjectivity of individuals in the most excluded regions. Thus, the intervention of the State is promoted by the "invention of tradition" and the expansion of the idea of a Brazilian nation (Chauí, 2000).

The actions of recognition and integration of local practices and customs make daily life particularly a national content; such is the case of folklore studies as the academic construction of the daily dynamics of the population. The attempt to define folklore and folk art as a national expression appears in the thirties, especially with the new representation of culture in Brazil (Cavalcanti, 1999).

From the studies of folklore and folk art, as opposed to "high" urban culture, the representation of craftsmanship and craftsman in the rural, peripheral and "occult" context of everyday life is constructed academically (Christensen, 1965; Meireles, 1968).

The studies on handicraft, such as symbolic construction and the politics of the product of craftwork, soon emerge from a new configuration of the labor market, enabling to define and know the situation of the workers outside the industrial urban regulation. From the regions, mainly from the northeast, it is tried to recognize the importance of the inclusion of the labor force to eliminate the subsistence economy.

In 1956, Carlos Pereira proposed a program for the development of handicrafts in Bahia (Pereira, 1956), together with the SUDENE (Superintendência de Desenvolvimento do Nordeste), created by Law 3692 of 1959 under the presidency of Juscelino Kubitscrek, encouraging recognition of the labor and craft situation in the region. In 1975, in São Paulo, the Superintendence of Artisan Work in the Communities-SUTACO- (SDECTI, 1975) was created, an autarchy (public administration) that sought to generate employment and income of craftsmen and the rescue of traditional expressions of the state of São Paulo, promoting mechanisms of delegation for social and economic monitoring.

The ethnographic literature grew in the academies in the sixties and seventies, in the context of “Cultural Revolution” in Europe and America, which consolidates the formation and classification of studies of non-industrial work (Mendonça, 1967). In other words, a definition of the social expression of daily life, of the regional economic inequality of the market and of its political exclusion by the citizens' rights, becomes in these years cultural practices of artisanal production; In addition, it becomes the field of struggle for the recognition of craftwork for regional development. Thus, recognizing the lack of integration and population control, taking into account the economic, technical and organizational limitations of most of the territory, the national government policy of handicrafts was defined, establishing the National Handicraft Development Program (PNDA) under the Ministry of Labor, with to Decree-Law 80098 of 1977, which had as its object the "promotion of the craftsman and the production and commercialization of Brazilian handicrafts" (Brazil, 1977: Art. 1). It is important to recognize here that the basis of the definition was on the object, not on the producer as the axis of politics.

The political consolidation of craftwork

Taking into account the characteristics of Brazil within the international division of labor, Ernesto Geisel's government proposes a definition of artisan and craftsmanship to delimit the area of political action, considering that the classification is part of a governmental strategy to adjust the work to the capitalist economic structure in the national territory.

Decree 83290 of 1979 regulates the artisan activity in relation to the codification of handicraft products within the PNDA, and the registration of artisans as a process of production of identity before legal identification of agents and their activities (Brazil, 1979).In this case there is the production of subjectivities of craftwork as a construction in the twentieth century for integration into the labor market, through the homologation of the cultural value of the regions, taking into account the historical social inequality of Brazil and its geographical extension.

The guidelines presented by the PNDA sought to formulate the artisan within the labor rights reached by industrial workers years ago, materializing this in the Labor Card and Social Security (CTPS), an effort of corporate integration of the informal labor force. The artisans had to be recognized by the PNDA to receive government support, as proposed only those identified with a labor card, reproducing the problems of the State for the universalization of social rights of the population in general.

This takes into account the difficulty of defining and identifying the artisan in a context of cultural diversity and regional exclusion in a country of continental proportions. Thus, identification was the requisite for the fulfillment of social and labor rights, creating a new exclusion within the workers, since only urban informal workers had a greater opportunity to participate in the rights.

Restructuring of craftsmanship, entrepreneurship and heritage

By the end of the last century, the development of vertical and horizontal integration of craftwork is different. The first form has the pressure of the development of means of production with greater technology which produces changes in the needs of the population, urban population growth, technological changes that render obsolete the manual labor skill of manufacturing and repair, changes in the growth of professionalization in the structure of labor.

This can be explained by the dynamics of capital in the specialization of production of machinery and technological means that allow the reduction of the necessary workers in inverse relation to the growth of the population qualified for work, generating misalignments of the needs of the capital against the possibilities of occupancy of workers (Marx, 2011).

The contradiction of labor and capital generates greater displacements after the 1980s, turning obsolete skills and means (tools and machinery) into the productive sectors of each country facing the new technologies of production, organization and communication.

On the other hand, the horizontal integration in the conditions of production in regions peripheral to the industrial capital could maintain forms of production with cultural recognition (artisan and handicraft), in this way the handicraft is consolidated as cultural work.

At the end of the last century, craftwork appears to be a growing activity, because informality and structural unemployment grow (Martins, 2009). With the changes in working conditions since the 1980s, the economic downturn in Brazil and the political reforms of that period, the social and economic context forces a growth in the population's participation in activities vulnerable to low unionization and high dispersion.

The growth of individualization, the multiplication of forms of social identification, the flexibility of working times, the rapid displacement of populations inside and outside the country, the growth of communication and information technologies, the labor market movement in globalization, the growth of outsourcing, among other phenomena (Antunes, 2002) constitute a new panorama of recognition and integration of craftwork.

Work structure and craftwork

With the restructuring of the work after the 1990s (Sotelo, 2003), the growth of the services sector and the decline of industry and commerce, the country's economic situation changes due to new productivity standards that allow the specialization of knowledge and skills required for integration into the labor market.

The new configuration of the work breeds a greater concern for the integration of vulnerable population, which produces the intervention of public cultural policies especially in the artisanal activity. There is a problem in measuring activity from its significance to labor organizations and cultural organizations. For the classifications of the labor organizations the craftwork can be measured in terms of vertical integration. On the other hand, since the heritage conceptualization, the classification seeks activities of cultural significance that identify the knowledge of the artisan and its heritage cultural production in the craft. The contradiction resorts to academic production and the possibilities of its measurement.

To understand the contradiction, we can understand the limits of each measurement and contextualize its relevance in a longitudinal and cross-sectional study. From a longitudinal study, to analyze the conditions and changes that this has in the craftwork, the relations of the position or situation of the workers in the structure of occupation of the population can be studied. For Brazil, based on data from CEPAL (CEPALSTAT), during the last fifteen years there is little variation between occupational categories, so between 1990 and 2014 there is a larger number of employees with an average of 57 and 26% for independents or self-employed, 4% for employers, a decrease of unpaid family members with an average of 5 and 7% for domestic services.

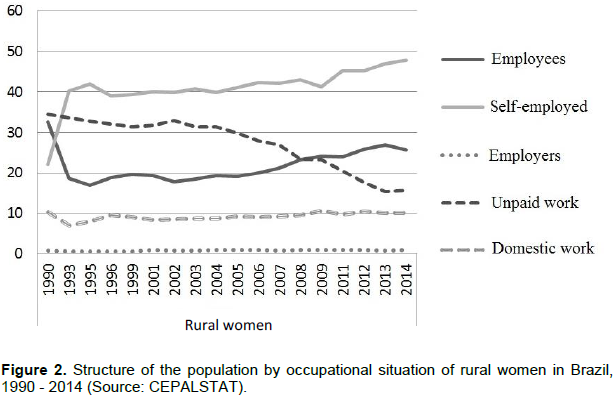

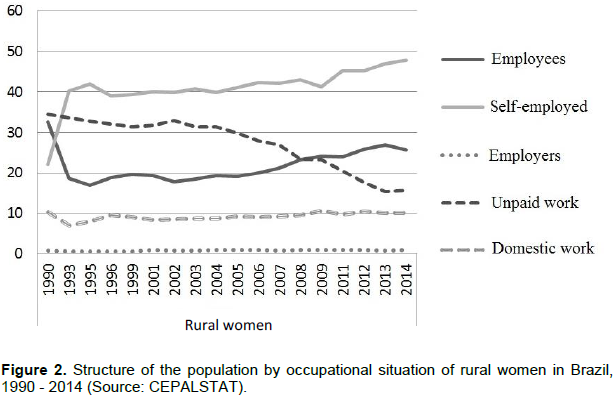

Taking into account the characteristics of the geographical and sexual division of labor, it is difficult to maintain homogeneous data in the labor situation. Thus, total data require a particular assessment by region and gender for analysis. The main variation with self-employed growth can be observed in rural regions, which represents a smaller population, 16.3% of the total for 2010, where there are 48.7% for the year 2014, with a difference of over 10 percentage points for employees (35.7%) and 21.7% for self-employed in the urban area. The main reason is that the variation and greater number of self-employed in the rural region is a result of the market integration by the women, since there is a decrease in the unpaid family occupation to the activities of labor enterprise (Figure 2).

There is a growth in the country of the self-employed or own account due to the condition of the labor market after the 1970s (Pochmann, 2012), which requires a change in the alternatives of integration to the market through the non-collective way. In this sense, self-employment still does not surpass the salaried work situation in the country, but allows us to identify that the movements of the population structure in the work of self-employment based on entrepreneurship acquire greater representativeness in the rural versus urban sectors, allowing to identify as cause the political changes since the nineties, mainly in the strong intervention of job creation relatively easy to integrate into the market as is the craft work the difference of specialized professions.

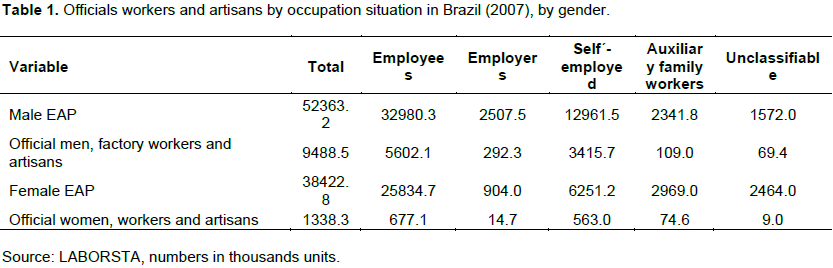

As a cross-sectional study, the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ILO, 1968) is used, which defines groupings of trades that allow a panorama of the division of labor in societies. In this case, the main group that welcomes the craft occupations is "Officials, workers and artisans of mechanical arts and other crafts," although the defining characteristics are social and cultural product of each country (Table 1).

For the year 2007 the population of workers and artisans represents a total of men and women approximately 12% in front of the total of the Economically Active Population (EAP). In relation to the total number of men, they present 18.2%, compared to 3.48% of women, which can be explained by the greater participation of women in services and trade activities in the labor market.

It is important to recognize that the self-employed have a larger share of the total for women, approximately six million, compared to female wage earners. More in the group of officers, workers and artisans is a much smaller number than men, in total number and by condition of salary, employer and self-employed.

It is difficult to recognize the particular participation of artisans in ILO data since occupational totals, considering that they are not all part of the cultural concept, in relation to craftsmen and handicrafts, but a very important fact is presented at the macro-structural level taking into account that the classification of occupations show a particularity in relation to self-employed on the basis of entrepreneurship, since the majority of men are salaried in a greater proportion to the ones of own account, unlike the women who have a relatively similar weight like salaried and as self-employed, the which explains the difference in the labor relation of gender and the type of occupation (Table 1).

National policy and fragmentation of craftwork

In this section it is exposed the diversity of the political relationship in the construction of national and regional

government programs that focus on the contradiction of the definitions of the craft. In the government of Fernando Collor, the Brazilian Handicraft Program (PAB) was established under the Ministry of Social Action, under the decree of March 21, 1991, passing from the conception of crafts and craftsmen with labor training at a level of industrial organization, to a policy of support and promotion to the entrepreneurship and the individualization of employment.

The program aims to "coordinate and develop activities aimed at valorizing the Brazilian artisan, raising his cultural, professional, social and economic level; as well as developing and promoting handicrafts and artisanal enterprises" (Brazil, 1991, Art. 1).

In the neoliberal economic context in the 1990s, the PAB changed its subordination in Cardoso's government, under decree 1058 of 1995 and became part of the Ministry of Industry, Commerce and Tourism (Brazil, 1995), although it did not change its objective, but the budget is defined in the policies of business development or entrepreneurship.

In this way, the entrepreneurship of craftwork by the condition of articulation of the system of production and consumption in globalization, acquires subordination to the mechanisms of accumulation and expansion of capital, which ends up in a control of identification before classification or registration in a national labor system.

Thus, the continuity of the PAB allowed, at the beginning of the 21st century, to strengthen two activities of formalization of handicrafts, support to the commercialization and training of craftsmen in front of the Brazilian Cadastral Information System (SICAB) with coordination’s in all states of the country and contains two instruments: the first is the Conceptual Basis of Brazilian Craftsmanship (2012), which is an effort to organize the craft discourse, where a consensus is reached on aspects such as delimitation of crafts, forms of organization, typologies of craftsmanship, classification, functionality, among others.

A second instrument is in charge of the registration of craftsmen in order to achieve unified information data (Brazil, 2012). The identification of artisans with the National Craftsman's Card and the National Manual Worker's Card was established in 2012, the idea of the registration of artisans was recurrent in previous programs since the 1970s, although the identification process only continues after 2012.

The scope is still few, with numbers for 2014 of 103,823 artisans and registered manual workers, considering that the quantity of artisans can exceed 8 million (Loureiro, 2015). In the Government of Dilma Rousseff under Law No. 12,792, of March 28, 2013, is created the Secretariat for Micro and Small Enterprises of the Presidency of the Republic (SMPE / PR), and transferred from the Ministry of Development, Industry and Foreign Trade to SMPE / PR the coordination of craft policies. Thus, the PAB continues with the Decree No. 8,001 of May 10, 2013, focusing on the artisan's work as an entrepreneur.

Although the PAB is the most comprehensive government program, other programs of direct or indirect political action are part of the intervention and promotion of craftwork, although they have different purposes depending on the cultural, heritage or economic definition. The ArteSol Program appeared as a project to combat poverty in 1998 and 1999. In this context is created the Program of Support of Artisan Communities (PACA), articulated to the government of Fernando Cardoso. This was a program that sought "the valorization of the artisanal activity of Brazilian cultural reference, for the safeguarding of intangible cultural heritage and the citizen's and productive inclusion of artisans" (ARTESOL, 2007).

The experience of working on three main axes of culture, education and economy, allowed that after the implementation of the PACA at the end of the nineties it would continue as a more autonomous proposal in the present century. There is a transit of regional governmental program until the year 2000, for autonomous organization before the figure of Civil Society Organization of Public Interest (OSCIP), which constitutes it as a civil agent with contract of activities in partnership with the State under Law 9,790, Of March 23, 1999.

The objectives are the rescue, promotion and development of the traditional craftsman and handicraft as a material and immaterial cultural through of fair trade and sustainability, which allowed organizing more than 98 projects and actions in 17 states by 2007. For the year 2013 the ArteSol Network Project was created, "the Network operates through a virtual platform that has a mapping of masters, artisans, associations and cooperatives, classified by artisan typologies and localities" (ARTESOL, 2014). In this network, there are more than 60 groups and serving more than 300 people in the production chain in several states.

Another program that aims to promote and support traditional handicrafts is the Cultural Tradition Craft Promotion Program (PROMOART), derived from the activities of the National Center for Folklore and Popular Culture (CNFCP), an administrative organism dependent on the Institute of Historical Heritage and National Artistic, Ministry of Culture. As a national policy projection for handicrafts, PROMOART seeks to immerse traditional handicrafts in the market as a series of products differentiated from other forms of handicraft. It seeks to adjust the conditions of cultural communities, proposing "the establishment of partnerships with different institutions at community, local, regional and national levels; seeking to consolidate co-participation and co-responsibility networks that enable sustainability of the initiatives undertaken "(Gomes, 2011).

On the other hand, there are programs of organization in search of resistance to the capitalization of the activity, with emphasis on the collectivization of income, in this context arise alternative forms of work and associated and collective income, what is known as solidarity economy. These programs were established in the 1990s in entities such as the Development Solidarity Agency (ADS) and the National Association of Workers in Self-Management and Shareholding Companies (ANTEAG).

For 2003, the National Secretariat of Solidarity Economy (SENAES) was formed through Law n. 10,683 and of Decree n. 4,764. In figures of this activity, handicrafts comprise about 9% of the enterprises, is an activity transversal to projects of regional development, micro and small companies and programs of work, employment and income (CENS, 2012). Its quantity prevents that it is still a proposal of magnitude representative of the sector, and carries the problematic of the channels of commercialization and consumption in front of the magnitude of the national markets.

The consolidation of craftwork in Brazil took place in the horizontal form of ethnic and cultural integration as a requirement for the identification of the artisan as a producer of handicrafts, thought of as "indigenous", "traditional", and so on.

The promotion of craftsmanship focused on the mapping of cultural activities in the rural population, allowing reproducing the narrative of cultural identities (Anastassakis, 2007). But the problems of the economic crisis of the 1980s made, the proposal unfeasible for the lack of a public employment system, enabling the articulation and integration of both the formal and the informal population in the labor market (Pochmann, 2006). Particular incentive and promotion initiatives in craftwork would diminish in the eighties by the restructuring of work, technological changes and new forms of labor organization.

On the other hand, in both vertical and horizontal integration the changes are significant, since the labor activity appears as a form of production with greater participation of women in the rural scope in the organization of work on their own, in the activities of artisan production in the technique of embroidery, with wood and typical cuisine, which allows us to define a phenomenon of economic restructuring of craftwork in the face of the industrial economic structure of the last century.

Although there may be manual labor activities in cities, with simple and specialized technical capacities that can be objectively recognized as handcrafted, they are manufacturers and restorers of objects, construction auxiliaries, etc. The definition of craftwork is now identified, promoted and protected from political actions in the sense of integration to the labor market in a horizontal way; that is, by the cultural political construction of the activity that requires constantly redefining the identification of craftsmen and craftsmanship between government and workers (Madeira, 2016).

In relation to the PAB, actually the principal government program of artisans, this is part of two important phenomena for the direction of artisanal labor in the accumulation and expansion of capital, the first in direct relation to the artisanal, where the logic of the pattern of accumulation of capital in dependent or peripheral countries can reinforce old labor relations derived from traditional systems, integrating them into the urban informal sectors (Sotelo, 2003), a product of the recessive cycles of capital and the growth of "available labor", resulting in greater vulnerability of job.

The second aspect has to do with a change in the logic of capital expansion, of the form of labor exploitation of the Fordism system to the Toyotism (post Fordism) system, because there is a "virtual capture" of social life by capital, the person presents himself as if he were a company. "It is the social life that intervenes in a virtual sphere of production of value. Life is business. Life becomes 'the most precious capital'. The society of toyotism is a society of producers, that is, a society of universal productivism, which is expressed, for example, through the lexicon of 'human capital' "(Alves, 2008).

The complexities of political fragmentation in the interests and objectives for the institutionalization of craftwork have produced a problematic image of the situation in search of legal regulation of the activity. Thus, the recognition of activity as a profession in Law 13,180 of 2015 cannot be considered as a process of consolidation of contradictions; on the contrary, it is a new legal and power plan of the dispute for the production of public policies. Understanding that the difficulty also includes the regional diversity of the country and not only its national magnitude, it is pertinent to recognize the local and state political conditions that integrate the forms of organization of craftwork.

In this way, an analysis of the craftwork in its restructuring after the eighties implies thinking about its form of relation with the fragmentation of the division of labor (Mészáros, 2002) and its characteristics in the political organization as seen in its promotion in the last years. Thus, to the difference of institutionalization in industrial society, the craftwork has the following characteristics in its restructuring in the globalization of capital:

1. A division within the craft occupations, that is to say, a specialization of the activities and objectives, integrating the cultural value in relation to the entrepreneurial formation and the identification of the craftsmen. It can be understood thus the formation of a field on a logic of cultural and economic capitals on the competence of groups and individuals by the best positions in the social space (Sapiezinskas, 2012).

2. In addition to the differentiation with industrial products, which constitutes their institutionalization, there is a fragmentation of luxury and artistic objects in the national market, which allows us to understand the intervention of designers in the production of handicrafts for competence with objects of cultural distinction.

3. As part of an international market, there is a fragmentation of work in the specialization of products for international marketing, increasing the competence of manufacturing products, resulting in an aspect of competence of luxury products, which ends up generating a greater probability of exploitation of the work of traders to producers.

4. A fragmentation of labor as part of the dynamics of capital that allows mobility of resources for expansion in micro-enterprises, of which represents productive work as part of the valorization of capital, not only manual labor but incorporating "cultural value". In this sense, integration presents itself as a response to the changes of the labor class to the classes-that-live-of-work (classe-que-vive-do-trabalho) (Antunes, 2005), which includes the population expelled from work or formal stability as a social precarization of labor.