Full Length Research Paper

ABSTRACT

This paper aims to expand and investigate the existing intersection parameters of daily life rituals in seven Muslim women’s academician public and private spheres by including alternative theoretical perspectives of COVID-19 social isolation phenomena that have not been socially explored before. Autoethnography is the methodology applied to answer how and to what extent these intersections have affected living space, time, and tools. The study has revealed a significant intersection of women-related obligations in the public sphere with private sphere responsibilities affected by COVID-19. Moreover, the study re-evaluated the existing literature on the public and private sphere, female gender, especially related to the concepts of discipline, surveillance, and self-censorship. Finally, it has revealed possible intersectionality relations to the metaphors of post-traumatic experiences of these seven Muslim academicians.

Key words: COVID-19, Muslim female academician, public/private sphere, Foucault, autoethnography.

INTRODUCTION

Undoubtedly unexpected, COVID-19 hit the political, economic, social and health life of the world in 2020 with its life-threatening consequences. COVID-19 showed its impact on countries like Bosnia and Herzegovina and Turkey almost simultaneously in March (Euronews, 2020). In view of the current situation surrounding the global outbreak of the coronavirus, most educational institutions have decided to gradually switch to online teaching while complying with the official curfews. In order to create this quick unplanned order, scholars began to work on all of these academic requirements, but gender inequality became an important yardstick for academic requirements. Recent publications on the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic by gender underscore that COVID-19 has led to unprecedented closures of daycare centers, schools and workplaces, reflecting the challenges in the areas of disclosure, teaching and tightened administrative requirements. The data in the article shows that women are spending more time on childcare and homeschooling than men during the pandemic (Gabster et al., 2020). This study was therefore designed at the earliest stage of the pandemic to provide scholarly insights from a group of Muslim women who suspected some exclusion and unconscious possibilities of prejudice and who had already experienced diverse challenges in the male-dominated institutional culture. Women in their meetings, inquire into the question of this invisible wall 'where the public sphere begins and ends, where private sphere begins and ends” (Costa, 1995:7-16). The main research question of the article seeks an answer to what extend these seven Muslim women academicians experience significant overlap in their public/private spheres.

Although as academics, have seen the indisputable fact that the COVID-19 process has burdened women with more responsibilities in the private sphere, and although their production responsibilities have peaked, according to a Washington Post blog report, a parallel to the Institute's report of the Fiscal policy reveals a dramatic gap in the division of domestic responsibilities between the sexes: childcare and housework responsibilities are mainly assumed by mothers, who spend 10.3 h a day (2.3 h more than fathers) and 1.7 h more housework than fathers spend (Andrew et al., 2020). Although this quarantine brought no immediate change in our lives, we were able to talk and question the issues encountered on the platform to censor and shape some facts and views from the perspective of intersections in the private/public sphere in terms of time, space and tools. In modern postmodern societies, Nowotny et al. (2003:179-194) argue that the boundaries between private and public spheres of science have merged and the two strands are now co-produced as a slogan that women are oppressed not only because of the capitalist, modern order, but also because of the patriarchal structure enforcing private sphere.

When all these consequences of the pandemic were analyzed from the perspective of women's studies, the first finding was that our traditional husbands, mostly religious husbands, under pressure from society, have not contributed to many private duties. Most of the intersectionality is primarily experienced between her two accomplished roles: being mother and academic and wife and academic. As Doucet (1996) points out, women do most of the housework in the private sphere, although they are socially active and productive in the public sphere. Researchers in this study emphasized that they either hated or were fed up with asking for task-sharing, and our expectations of our husbands began to change during this lockdown. The idea of this research structured, in particular, an examination of Habermas' analysis of public research along with Foucault's discipline might contribute partly to understanding how the mechanisms of surveillance and self-censorship impact the daily life of women academicians with these types of life requirements (Habermas, 1974; Foucault, 1979).

Most of the intersectionality is primarily experienced between her two accomplished roles: being a mother and academic and a wife and academic. Unexpected results were shared and reflected during their online lectures, disturbed by their children or husbands. This made them appear unprofessional in public. On the other hand, the working time as an academic in the public sphere was indirectly lengthened by the expectations of members of private life and their responsibilities as a wife and mother. Additionally, our own experiences and research during COVID-19 as research co-authors will add to the richness of autoethnographic stories and literature about the dramatic global pandemic of the 21st century.

METHODOLOGY: AUTOETHNOGRAPHY OF SEVEN MUSLIM ACADEMICIANS

An autoethnographic methodology, which newly and extensively begins to apply in scientific publication. It is a research method that helps researchers to self-observe, reflect, think about, understand, and interpret our experiences for ourselves (Wall, 2006: 146-160). The analysis methodology of autoethnography is based on reliability and usability as essential conditions for the collection of empirical material. These seven female academics as researchers from the discipline of management, and natural science found autoethnography as the unrelenting impetus of the world of traditional science with a wonderful, symbolic, and emancipatory promise for the implementation of the empirical materials of the research. Their autoethnographic diary in the online encounter in the private/public sphere reflected the daily observation of their everyday life, and the demand. As these seven Muslim academics are personally experiencing the limitations of the pandemic, they have recognized the importance of using introspection of autoethnography as a source of empirical material on COVID-19 (Bochner and Ellis, 2016; Ellis, 2016).

As a member and leader of the group, Prof. Topcu recognized early on the lack of research studies on the pandemic in all areas of life. At that moment, she decided to specifically select seven female academics from different places to start a project called Korona Akademisyenleri and bring them all together in a Whatsapp group on March 30 at 21:17.

This selection was based on gender, occupation, religion, language and experience of exclusion (unconsciously or consciously biased) from the public sphere.

All participants speak Turkish and come from Gaziantep, Sanlurfa, Mardin, Elazig (Turkey), and Sarajevo (Bosnia and Herzegovina). All have international experience from India, Germany, Austria, the USA, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and other parts of the world. Six of them have children, four of them are married and their spouses work, one of them is single and lives with her sister, and two continue their lives as single managers. After explaining the purpose of the project and reasons for joining the group, all members decided to hold the first meeting on April 1st, Wednesday, at 17.00h. for Turkey and at 16.00h. for Bosnia and Herzegovina. These seven academics met twice a week, Mondays and Wednesdays, via a visual online meeting platform and began the process of collecting empirical material with long, unstructured discussions about how and in what ways the COVID-19 process affected their lives influenced. An autoethnography relates to both the process and what emerges from the process because in the process these women not only produced a scientific product but also formed friendships: these quarantine days meetings became activities and encounters with each other (Bochner and Ellis, 2016; Ellis, 2004:32). All of the scientific bodies of autoethnographic methodology mentioned in this part of the research contributed their unique, profound criteria for the significant and correct application of the method in such social factors.

The research becomes a transformative perspective with its unique method of autoethnography (Creswell and Creswell 2017:64). The hermeneutic circle model (Bochner and Ellis, 2016) applied to the analysis of the empirical material expresses the concern of experimental writings by confronting the conditions of representation and subjectivity.

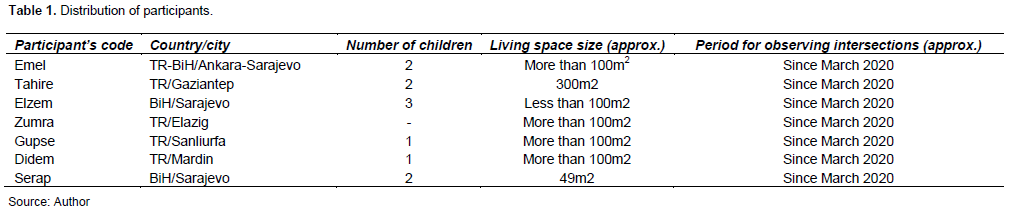

Because it allows for the interpretation of textual data transcribed based on the experience of research participants and comprehensively provides space to underpin the meaning of daily life, human practice and cultures with philosophical possibilities. The participants, with the exception of the authors of the article, are coded with a pseudonym. Table 1 shows the distribution of participants.

FINDINGS

The auto-ethnographic findings revealed the experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic in terms of time, space and tools of seven female Muslim academics and confirmed significant intersectionality in their private/public spheres.

Intersection in space in the private and public sphere

This part of the study discussed the intersections in the private sphere such as housing and answered the following questions: How did the size of a house affect the process? What was the actual effect of marriage and having children on women in this social quarantine process in the private sphere? What has put women under the most pressure in the private sphere as modern women who belong to the public sphere? Where should we have moved our office and which spatial elements strengthened our sense of belonging to the public space? Although participants experienced participation in online sessions of conferences worldwide as an inevitable fact that their productivity peaked in this process of social isolation, they also experienced reduced functionality as a representative of women in the public space after being brought into the private space . In this part, the intersection process in relation to the living space is presented using the precise thoughts of the participants. Those of us who lived in smaller neighborhoods and had children were more affected by this intersection process. On the other hand, the bachelorette continued to maintain her privacy by creating the public in the home and enjoyed the functionality of the public and continued to produce in her public.

Metaphoric reflection of private sphere: Is it a home or a graveyard or the belly of a great fish?

In this part, the focus is on analyzing both the emotional and metaphorical implications of the stay-at-home aspect from the perspective of the research participants. Participants affirmed that we as females were afraid of staying at home or privacy in this modern age, but ‘this unexpectedly became a revision process in our lives’ (Gupte, April 1st, 2020 - 1:05:35 min.). ‘We were happy to be in privacy until this process stopped being temporary and our worries, even our fears and nightmares of being locked at home started resonating in our heads. Because of the social quarantine, we began metaphorically comparing our homes to some well-known religious concepts, such as a tomb and the belly of a big fish; ‘this process reminded me of life in a grave, which has no temporal and spatial coordinates’ (Elzem, April 8th, 2020). Alternatively, we have revised our relationship to the Qoran (the holy book of Islam) and our religion by finding a connection to the Prophet Jonah: ‘Our impatient state of being at home reminds me of Jonah's impatient state in the belly of a big fish and his prayer to Allah’ (Didem, May 10th, 2020 - 2:09:16 min.). Other important independent variables in this process are the size of our homes and marital status. The small apartments and houses caused the participants some concerns about an organization with other household members: ‘In Bosnia, our houses and our living quarters are not suitable for a full-day stay at home with two or three children due to their small size. I had to bring my things home from my office. Now I don't have enough space to store them’ (Elzem, April 6th, 2020 - 22:26 min.). However, participants living in larger houses did not experience as much intersectionality in terms of house size and chores. ‘Aside from setting up my workplace in the house, we set up a room with a desk for my sister to give her a sense of belonging’ (Zumra, April 6th, 2020 - 75:35 min.). Some of the participants considered spending their time with their loved ones, regardless of the size and conditions of the available space: ‘even if the size of the house in Bosnia and Koycegiz is more appropriate for this process, the house in Ankara is where I prefer with my son than alone in other houses’ (Emel, April 6th, 2020 - 8:00 min.).

Lecturer in the classroom in public sphere and mother in private sphere

Taking into account the demands of public and private sphere, spatial overlaps reach our limits in special situations like preparing our classes when our children and husbands are at home. When our kids needed space to draw with crayons, we looked for a convenient place, like the ironing board or the kitchen counter, to put our laptop down and prepare for a lecture. In addition, children, being part of the house rhythm, became one of the most dynamic rhythmic elements of the routines that intersect the public space with the quarantine process: ‘children are best suited to transform the space because children spontaneously use their physicality to everyday life by teasing the other members who are at their home, and this creates an opportunity to observe the transformative power of the children on site’ (Gupse, April 6th, 2020, 65:00 min.). One participant mentioned that not only academics in modern times are behaving as if they have unlimited time and space, or not only adults but also children are inexorably behaving as if they are being held by a büvelek (warble-fly): ‘In the modern In life we ??rush everywhere like a horse that is held by a buvelek while we play our roles... we got locked up, we stopped, got rid of bvelek and started to make sense of many things’ (Elzem, April 22nd, 2020).

At the beginning of the epidemic, the situation looked like this. We have tried to engage as much as possible with all the activities around us.

The participants with children admitted that their children and husbands turned out to be their observation variables in order to understand this process. The life of these mothers looks like the life of a horse that is caught by a warble-fly and constantly produces activities for their children.

‘Because children are used to spending time with their parents playing rather than learning through play, there has been a large overlap between their parents' work hours and their habits as their parents struggle to meet the needs of public space. Most of us have similar experiences with our children growing up: my daughter always wants to do something, for example she wants to play games without a break. She has no tolerance for adult fatigue. She also doesn't stop when I tell her I'm tired. She offers an alternative, like painting while we can both sit’ (Didem, May10th, 2020 - 2:07:36 min.).

Some of us took advantage of technology to stay in control of the kids during our online classes: ‘We live in a two room apartment (originally it was 1.5 rooms), my concern is how I want privacy and can protect my duty as a mother and technology ? Especially in class, when children appear in front of the camera, I feel unprofessional’ (Serap, April 6th, 2020 - 37:07 min.).

Although one of the hottest topics, especially in times of the pandemic, is the question of the compatibility of work and child-rearing mothers, the discussion was included the study.

Views the public sphere over the balconies and windows of the private sphere

In the process of social isolation in our lives, balconies and windows have acquired a different meaning than spaces that give us access to the public: ‘we need to be aware that it is a time when we need to think about our space practices’ (Gupse, April 19th, 2020 - 10:00 min.).

For most of us, balconies became places for our sociology students to do their homework and, above all, areas of research for us: from my window and balcony I watch the people of the city at the traditional Sunday barbecue. In the second week (after the social quarantine), the neighbors decided to move their barbecue party from the picnic area to the balcony. I understood the situation: ‘the way we use space is changing now; this is a serious transformation of our spatial practice’ (Gupse, April 19th, 2020 - 10:00 min.). In public we had a producer feeling, but privately we live in a part of the world where we watched a party from the window and balcony.

From time to time, balconies turned into places where we applauded healthcare providers or turned to a place where we picked up a token of our freedom. Our balconies and windows allow for images outside of where we live: sometimes it was the view of the setting sun, sometimes it was the blossoming trees with the joy of spring that our frames could have captured. Balconies transformed into playgrounds for children to communicate with their friends or an area not considered to be cleaned until the social quarantine:

…the windows on this balcony had not been washed for at least six months; I realized that there are too many windows on the balcony… Meanwhile, the next-door neighbor turned her chair towards us and sat down on the balcony. My sister and I tried to guess what she might have thought, and as a typical cleaning-loving woman who would be happy to see us could have thought - Wow, they finally got on cleaning those windows (Zumra, April 19th, 2020 - 30:00 min.).

No matter what we observed, no matter what we felt, we were once again grateful to our Creator for having homes with balconies that allow us gradual emotional transitions. A member of our group who was caught by COVID-19 underscored the importance of a balcony: ‘Yesterday my students came with their parents. We greeted each other from the balcony. We waved. It was very emotional’ (Zumra, November 24th, 2020 - 42:00 min.). Balconies and our window views became important tools that allowed us to move from the private to the public sphere.

The time intersections in the private and public spheres

During this process, we became aware of another critical intersection, which was the technicality of our everyday routines. Thinking was not part of our everyday life, going to work at a certain time, dressing according to a certain dress code, having breakfast, getting the kids to school on time, attending school at a certain time, leaving school, picking up the kids from school, preparing and eating dinner, washing the dishes... all these rankings, which are part of our everyday life, were carried out in a purely technical way:

…people thought, for example, we are at home, we are ready to do many things. We lost our ability to divide the whole day according to such a modern understanding again when we started staying at home. The house has its rhythm, and we broke our ties with the house. Maybe now we will start catching the rhythm of the house by being a family in a modern context (Emel, April 15th, 2020 - 10:00 min.).

The feeling of pleasure was completely alien to these life routines. With the shifting of the responsibilities of the public into our private sphere, all of our well-organized routines have been turned upside down. Although living without a schedule was a problem at first, it turned into a process that later brought joy. Having a no-schedule, no-time pressure life following the monotonous modern model has brought together many feelings and a sense of joy, crossing our path with the facts we had long planned. Also, we were amazed at first that getting out of the routine made us panic and at the same time the problem-solving minds started working harder to adapt to this new situation. So we started to think more critically about our old life routine and our new life routines that we should develop.

Time to awaken the white feminists in us

In doing so, we found that we were not able to meet many new requirements, such as sewing a mask, cooking every day, cleaning every day, cutting our hair. Some of us were giving lectures on our field and then suddenly we got into a process of online teaching mode. We enjoyed directing the lives of our students, but then everything turned upside down. As academics, we started developing fun activities for our students who had to stay home due to the quarantine, so they could have a more joyful and meaningful time with their siblings:

‘students who were not allowed to study out of town, returned home , and their only escape was the university campus, the only place where they could breathe and be free. Now they probably cook, do housework instead of homework and take care of their siblings all day’ (Gupse, April 6th, 2020 - 75:00 min.).

Although most of us wanted to be in the classroom teaching our students, we were trying to figure out what knowledge would be most appropriate at the time. Oddly enough, preparing a pancake recipe turned out to be the most valuable productive knowledge at the moment. Lectures on Foucault, Goffman, Hobbes, Habermas, C++, Management, Cognitive Psychology were of importance during studies. In this new situation, the knowledge we were imparting at the university was insufficient and we felt that we should also provide our students with other information. All of these intersections between our public and our private spheres have awakened the white feminist in us. It was obvious that we were incompetent for these new tasks because we didn't know many things like traditional cooking, sewing and even housework because we didn't want to be like our mothers. In the name of feminism, we have long resisted being traditional women; we were ready to be heterodox. However, the most needed things during this social quarantine were sewing masks, baking pancakes and baking cakes with our kids. Indeed, in this process we have found that the information about what is required at the moment has become more important; Unfortunately, other information wasn't that important:

‘the little things we tried in this process, this chaotic situation reminded us of before, for example collecting the leftovers after our grandmothers finished sewing’ (Zumra April 6th, 2020 - 95: 00 min.).

Due to lack of time and fast life of classroom teaching mode and online teaching mode, especially in academy, we were unaware of the importance of these traditional products made by our mothers and grandmothers. The main reason for these memories of the past was that the brain, free from the constraints of time, got out of the routine. In order not to neglect this production, which always existed in the private sphere, especially for women, it could not be evaluated by the standards of the capitalist order. Women who cook with children and engage in distance learning had to direct the lives of their students and show their productivity by showing up again and again in the groups, student platforms, educational and informational platforms they formed.

Fitting the all requirements of public and private sphere in the Holy Month of Ramadan

Ramadan 2020 began on the evening of Thursday April 23rd. The meeting right before Ramadan was on April 22nd and we started to reschedule the time of our meetings according to Iftar and Salah time: ‘There is one more thing, the month of Ramadan is coming, when do we meet [laughs]? I think it will be a little less productive. I have even moved my classes to night, but if this is a situation that will affect you too much, I will follow you; I will do as you say, but I prefer the night because we do not sleep until dawn and go to bed after morning prayers. So [laughs]’ (Didem, April 26th, 2020).

The question was fully related to all aspects of the coronavirus incident. What was our new routine? We have tried to understand this change. How long can our old life go on now? Was the old normal or was the new normal? Was our new normal our real normal?

Ramadan experience, especially after moving to Elazig, is different for me. I wanted to have an iftar outside, but booking for a single person is not possible where I live; restaurants did not want to give me a table [laughed]. After this painful experience, this Ramadan, I can eat regularly, both at sahoor and in the evening with my sister. Here in this situation, we are experiencing the beauty of Ramadan. It is a very positive effect for me to

experience peace and happiness (Zumra, April 26th, 2020).

While some of us found joy in meeting at a restaurant for iftar time, others enjoyed being alone and socializing less. The notion of sociability in this context encompasses rich traditions, norms and rituals in eastern Turkey: ‘My children and I are together and the three of us have different ways of spending time together, when my son went to sleep we woke up. We could not meet at the table for dinner before this Ramadan. Now, thanks to Iftar, we can sit at the same table. That was the beauty of Ramadan. You do not get tired in terms of socializing because you do not have to go out to prepare your home for a crowded iftar table; it is easier’ (Tahire, April 26th, 2020). During Ramadan, we became online guests in each other's homes and kitchens to help prepare for iftar time: ‘I'm making a pie with minced meat because I have an hour left until iftar. Having Ramadan at home is better because my daily routine in the previous Ramadan was difficult to organize with tasks in university, cooking, childcare, housework. All of these were my duties. Normally I couldn't catch up on time in Ramadan, but now everything can be arranged without any problems’ (Didem, April 26th, 2020). It was symbolic to meet at this time to keep alive one religious ritual and old tradition. We met online in private space to practice public events.

The tools intersection of the roles in the private sphere and public sphere

The intersections we experienced in the instrumental context emerged in concepts that we did not have to use in the private field. The headscarves we used in the public sphere, the intense use of our computers exposed us to the world during the pandemic. The same attention that was in the public sphere was used in the private sphere. Our computers kept us connected to the life in the outside world and brought us together with our loved ones. However, one of the questions we all asked during this process was how to reach the graves of our loved ones because no matter where they may be, we were unable to visit the graves due to spatial constraints, and we thought of our dead ones more than usual. Obviously, it seemed that we have now managed to adapt our functionality, which we achieved by using many tools in the public sphere of the classrooms, in front of the cameras on our computers during this pandemic. Suddenly, our computers became our world; yes, they allowed us to contact the world, but something was missing. It could not help us reach those who migrated to the hereafter.

The headscarf dilemma in privacy in front of the camera or not to wear

In our ninth meeting on April 29, 2020, the leader of the meeting listed the following questions:

So what role does the headscarf play in our daily life? What do we do at home? What do we do when we enter a meeting? Because the thing is, we usually wear the headscarf in the public sphere, we do not wear it in the private sphere, and how did our relationship with the headscarf changed in the private sphere? I normally wear my hijab in a more formal way when going out. But now, I do not pay much attention to my headscarf, especially on online platforms where I participate with people from my close circle. Actually, the headscarf is a tool we use when we go out in the public sphere. But now that we are entering the public sphere through online platforms, the headscarf has changed its meaning in the old public sphere (Emel, April 29th, 2020).

Women do not necessarily cover their heads or have to wear their headscarves at home, but in this new standard era, wearing a headscarf has become a necessity for most of us as we spend most of a day in front of the home computer in online meetings with our students or on educational platforms. Not just us, all family members had online meetings or classes, and in order not to appear in front of someone else's camera, most of us started wearing headscarves in private:

In fact, the headscarf is a tool that is not used in the private area, I am having an awful lot of trouble, and I am afraid of being caught by my children’s or husband's camera in my private sphere. When I look at our current life, even a simple act of serving tea to my husband became a torture because of the fear of being caught by his camera. I started admiring today what I was criticizing yesterday: a guest room in the Turkish cultural context because it is a necessity in these pandemic conditions, in our Big Brother concept (Ezel, April 29th, 2020).

Although only women held these meetings, we always went to the meetings with a headscarf because we were aware that others might see us in front of the camera: ‘We mostly wore our headscarves comfortably (Didem, April 29th, 2020).

‘But during the lecture, of course, I had to pay attention to my clothes and what they should look like. The university has already sent us an instruction to describe how to conduct our online meetings or courses’ (Tahire, April 29th, 2020). Finally, we tried to understand the reason for discussing this particular topic:

Headscarf is neither sacred nor symbolic; it is a rationality tool to communicate with the Creator. I love wearing headscarf because it provides me with a strong relationship with Allah; however, after I started wearing headscarf, the society began to see me as a Muslim, and they explicitly made me a representative of all women wearing headscarf. My mistakes were not anymore considered belonging to an individual or Emel. They started being the fault of all women with a headscarf (Emel, April 29th, 2020).

Computers: Device for survival and surveillance

During this process, our computers or cell phones continued to be devices that begin to feel expelled out of the public space when taken from our hands. The most important devices that give us the feeling of being in the public sphere were the most essential devices that enabled us to complete our online lessons by placing them on the kitchen counter in our small houses where we do not even have a work desk: “I brought my electronic devices from school to be able to hold online lessons; it is in a corner of the bedroom, close to the closet because there is not enough space to place it somewhere else” (Elzem, April 4th, 2020 –22:32 min.).

No matter how many of them a family have, it is never enough because they enable all family members to fulfill their public sphere responsibilities simultaneously on multiple computers: “I have a duty as a teacher to keep my children calm during this time; a mobile phone is the only tool to keep them away from another tool, my computer camera” (Serap, April 06th, 2020 – 37:07 min.). These devices did not just replace our class devices, “the camera functions as a surveillance mechanism as well” (Gupse, April 29th, 2020 - 26:27 min.). However, the computer in our house became the most important tool to connect to the outside world with our family members and organize activities, such as concerts, surprise birthday parties, etc.

DISCUSSION

The participants' auto-ethnographic self-reflection gains in importance when analyzed as a whole in the study. They were affected by various aspects of private and public interactions in their daily lives. This study aims to reflect all of their worries, fears and expectations of themselves. For this reason, the data collection is completed with the unique method of autoethnography. Overall, these transformation processes of COVID-19 are simultaneously becoming a new social phenomenon of the postmodern research agenda. It created a very traumatic juggling effect on the women in this study, particularly due to their traumatic past challenges of being part of the public eye through discipline, surveillance, and self-censorship. Publishing, teaching, and administrative duties intersected heavily with serving tea for their husbands, assisting with their children's activities, cleaning, cooking, and washing. In this context, by illuminating the perspectives on space, time, tools, and other outcomes of these breakdowns, intersectionality's analyzes and insights contribute to the literature on COVID-19 and feminism and to further research on renormalization solutions. The most striking feature of the study is that most of the participants wore headscarves, had previously been excluded from the public because of their religious beliefs and had a traumatic past in this regard. The fact that the epidemic pulled them out of the public sphere and forced them to exist in the private sphere not only resurrected their past traumas, but also caused them to reluctantly begin to share their experiences with what was left of the reflections evaluate the past. The importance of the autoethnographic method was seen here in closing the healing gap between public and private areas with the reflections of the participants. During the pandemic, their memories of past exclusion from the public sphere were awakened by combining the autobiographical impulse described by looking inward gaze with the ethnographic impulse of looking outward gaze. Every shared experience took on a special and valuable meaning for these women who were struggling to be in the public eye.

These results were chosen for this reason, to reflect their unique experience.

The COVID-19 crisis has evidently disrupted normal forms of outreach and participation in public life. In this sense, the old traditional public became inaccessible due to health risk factors. The lockdown of public space has gradually changed everyday life, lifestyle and culture by shifting all responsibilities of public space to the private sphere. Social distancing restrictions, along with their public lifestyle, initially pushed individuals into their privacy, where they were forced to attend to both public duties and household chores. Then the mask-wearing requirements forced people to use their computers or mobile phones to access online meeting platforms at local, national and transnational levels to catch up with their loved ones, students, friends and colleagues.

These insights and evaluations reintroduce our group analysis, which must cover the intersectionality of both spheres, because these seven Muslim women have made a conscious choice to be part of the public since childhood. Everyone became aware that public entry was only possible through studies and a job. Because of this, most of them refused to learn the traditional female chores, and most of us were incompetent in those roles. As part of our lives, intersectionality has been blurred with happiness in being in the public eye; However, the heavy intersection of privacy and publicity left us feeling incompetent with constant self-censorship. In this vein, women have also signaled that self-censorship falls short of their responsibilities in the competitive academic environment when it comes to publishing material that measures productivity in the public space. Public pressure, countable productivity, was an issue that made us, as representatives of the female gender, feel that we were not meeting the requirements because productivity in the private sphere was not supported to challenge countable production in capitalism's labor discipline Publicity. However, COVID-19 has opened the door for masses to inquire about this real burden on women's shoulders, as forthcoming studies like this one will reflect science from our homes as our fields of study to uncover reality.

CONCLUSION

COVID 19 and the quarantine have made us understand that we have all consciously internalized being part of the public eye as headscarf wearers and realize that we do not approve of the traditional female lifestyle. It was only in 2013 that six of the seven participants in the study in Turkey were given the right to work in public spaces with their headscarves on. COVID-19 has pushed many people out of the public eye and into the private sphere, and social quarantine has unleashed their deeply traumatized consciousness. There is panicked with the already experienced feeling of being alienated and isolated from the public again. While all do not accept feminism in the fullest sense, it was during this time that we discovered that there was a secret white feminist within us. We began to strengthen our relationships with public sector responsibilities. When we were locked in houses, participants from the east region thought that their students, especially their female students, were greatly affected by this situation. They tried to develop something suitable to keep them active in the private sphere.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Andrew A, Cattan S, Dias MC, Farquharson C, Kraftman L, Krutikova S, Phimister A, Sevilla A (2020). Parents, especially mothers, paying heavy price for lockdown. The IFS. (Accessed: 21 January 2021). Available at: |

|

|

Bochner A, Ellis C (2016). Evocative Autoethnography: Writing Lives and Telling Stories. Routledge. |

|

|

Creswell JW, Creswell JD (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage publications. |

|

|

Costa DM (1995). 'Capitalism and reproduction', Open marxism 3:7-16. |

|

|

Doucet A (1996). 'Encouraging voices: Towards more creative methods for collecting data on gender and household labour', in Gender relations in public and private. Springer, pp. 156-175. |

|

|

Ellis C (2004). The Ethnographic I: A Methodological Novel about Autoethnography. Rowman Altamira. |

|

|

Ellis C (2016). Revision: Autoethnographic Reflections on Life and Work. Routledge. |

|

|

Euronews (2020). 'Sa?l?k Bakan? Koca: Türkiye'de ilk koronavirüs (Covid-19) vakas? tespit edildi', |

|

|

Foucault M (1979). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. (Trans A. Sheridan). Oxford, England: Vintage (Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. (Trans A. Sheridan), pp. ix, 333. |

|

|

Gabster BP, van Daalen K, Dhatt R, Barry M (2020). Challenges for the female academic during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet 395(10242):1968-1970. |

|

|

Habermas J, Lennox S, Lennox F (1974). 'The Public Sphere: An Encyclopedia Article (1964)', New German Critique, 3:49-55. |

|

|

Nowotny H, Scott P, Gibbons M (2003). 'Introduction: 'Mode 2'revisited: The new production of knowledge', Minerva, 41(3):179-194. |

|

|

Wall S (2006). 'An Autoethnography on Learning About Autoethnography', International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(2):146-160. |

|

Copyright © 2024 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article.

This article is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0