ABSTRACT

This paper investigates the implications of smallholder farming, that is, characteristic of a community based water management system in Oman known as a falaj (pl aflaj). The aflaj are naturally sustainable, and for centuries have provided water in an arid region, supporting agriculture and livelihoods. With over three thousand active aflaj in Oman, the typical falaj is small; conveying enough water to irrigate a relatively small amount of land, and this water and land is further subdivided among many farmers. The implications of these smallholdings on the economic viability of the falaj were investigated by studying one falaj system. It is found the small holdings of water and land imply a typical farmer cannot realize economies of scale in farming, implying average costs are high and farm profits are low. As the aflaj are community managed, the low economic value of the falaj implies there may be insufficient funds for maintenance of the falaj, thus threatening their sustainability.

Key words: Traditional agriculture, water management, community based natural resource management system, smallholdings.

The implications of small land holdings in an indigenous community based water management system in Oman known as a falaj (pl. aflaj) was studied. The aflaj are small scale irrigation systems that have provided water for both domestic and agricultural use to small communities in Oman for over a millennium, thereby allowing for human settlement in a harsh, arid environment. The long history of the aflaj speaks to its success in sustainable water management, as well as to the importance and the aflaj to Oman’s heritage and cultural identity (Wilkinson, 1977; Sutton, 1984; Orchard and Gordon, 1994; Limbert, 2001; Nash and Agius, 2011). Their continued existence is important both because of the fact that they are a naturally sustainable source of water, and because of their importance to Oman’s heritage. There are over three thousand active aflaj accounting for approximately thirty percent of all groundwater used in Oman (Zekri et al., 2006). However in the post 1970 oil economy of Oman, the number of aflaj in operation has fallen by approximately twenty five percent (Aflaj Inventory Project, 2001). There are thought to be two reasons for this decline in the aflaj. The first is over-aggressive groundwater pumping has reduced the water table, reducing the flow rate of some aflaj to unsustainable levels (Norman et al., 1998; Dutton, 1995). The second reason for the decline in the aflaj is that the oil economy has led to a rapid increase in household income in Oman since 1970. This increase in income implies the economic significance of the aflaj has diminished, and thus interest in falaj farming has decreased, especially among the young (McCann et al., 2002; Bosi, 2009). Hence, increasing the profitability of falaj farming is important to the continued economic viability of falaj farms. Moreover, the decline in income from farming creates a threat to the maintenance of the falaj itself. Since the falaj is a community based water management system, the falaj community members are responsible for its maintenance (Wilkinson, 1977).

Typically, a falaj is managed by a committee which has been endowed with water to fund its maintenance. The water can generate funds in two ways. First, some of the water may be rented to community members using auctions. Second, some of the water may also be applied to falaj lands on which the falaj owns date palms. These falaj owned palms may either produce a crop that is sold, or the date palms themselves may be rented to community members (Al Marshudi, 2007). In all cases, the revenue from falaj owned water and falaj owned date palms provide the funds for maintenance of the system. Thus the amount of revenue for maintenance is derived from the economic value of the water and land of the falaj. If that value is low, the funds available for maintenance will also be low, thereby presenting a threat to its sustainability. As a result many aflaj suffer from sub-standard maintenance (Al Ghafri, 2004). Indeed, part of the maintenance in many aflaj is now carried out by the Ministry of Regional Municipalities and Water Resources (MRMWR), whereas for centuries it was supported solely by the wealth generated by the falaj (Al Hatmi and Al Amri, 2000). While there may be multiple reasons for the declining profitability of falaj farms, one potential reason is small land holdings. Through inheritance laws, the falaj land holdings have been subdivided many times over the centuries leading to small land holdings observed today. If economies of scale are present, small land holdings imply farmers will be unable to realize the economies of scale, and will thus have higher average costs, implying lower income generated from farming.

The purpose of this paper is to examine the economic implications of these small holdings on the productivity and sustainability of these aflaj.

This paper argues average costs tend to decline as falaj farm size increases. Such a relationship implies larger falaj farms are more productive. While economies of scale are present in many industries it is not necessarily present in agriculture. The relationship between farm size and productivity has been studied extensively in the literature. Early studies found an inverse relationship between farm size and productivity; that is, smaller farms tend to be more productive (Sen, 1962). Recently, Kagin et al. (2016) found not only do smaller farms have higher productivity, but they are also more technically efficient. However, Savastano and Scandizzo (2017) have found the relationship between farm size and productivity to be non-monotonic, with the relationship between farm size and productivity switching between direct and inverse. In particular, they found a direct relationship for very small farms, but an inverse relationship for moderate size farms, and again a direct relationship for large farms.Three broadly defined explanations have been offered for this inverse relationship. The first is market imperfections; particularly, imperfections in the labor market (Eswaran and Kotwal, 1986; Heltberg, 1998; Toufique, 2005; Henderson, 2015; Ali and Deininger, 2015). Hired labor has a tendency to shirk, making monitoring necessary, as well as reducing productivity. However, home labor does not have such a tendency, making costly monitoring unnecessary. Thus home labor is more productive. It was suggested that small farms tend to make more extensive use of home labor, and thus small farms are more productive.

A second explanation focuses on omitted variable bias. In particular, land quality may differ between small and large farms, and thus drive the difference in productivity. There is mixed evidence for this effect. Bhalla and Roy (1988) find evidence for such an effect, whereas Barrett et al. (2010) do not. Finally, a third explanation is the possibility of measurement error. Farm size is usually self-reported, and it has been suggested that small farmer misstate the size of the farm, introducing an error that artificially overstates the productivity. Again the evidence is mixed. Lamb (2003) finds evidence suggesting all of the inverse relationship between farm size and productivity can be explained by measurement error. However, others have found a more accurate measurement of farm size strengthens the inverse relationship between farm size and productivity (Carletto et al., 2013; Holden and Fisher, 2013; Gourlay et al., 2017; Desiere and Jolliffe, 2018). Recently, Nkonde et al. (2015) argued that since previous studies have focused on farm sizes limited to 1 to 10 ha, and the measurement of productivity is limited to a single measure, the findings in these studies provide an incomplete understanding of the relationship between farm size and productivity. When these limitations are relaxed they find that the relationship between farm size and productivity is less clear and depends on the productivity measure used. In this paper, while we focus on the relationship between falaj farm size and average costs, the link between productivity and average costs are clear. All else constant, higher productivity will yield lower average costs. And while much of the literature has found some evidence that smaller farms are associated with high productivity (and thus lower average costs), the opposite was found. That is, smaller falaj farms face higher average costs when compared with larger falaj farms from the same falaj.

To understand this result, it is important to note that the explanations focused on in the literature are not applicable for farms from the same falaj. The reason is that falaj is a community and the farms that comprise it are similar with respect to the variables that have been identified in the literature. For example, while labor market imperfections may exist, it was found out in this study that home labor was not used by falaj farmers. Hence, all faced the same labor market imperfections, and thus this cannot drive any cost differences between small and large farms in the falaj. Similarly, the omitted variables focused on in the literature are unlikely to be relevant for falaj farms. Regarding land quality, the falaj in its total size is small and thus all farms belong to the same relatively small amount of land, and thus the land is likely to be of similar quality. Lastly, one may consider measurement errors of small farms. It is important to realize that all farms in a falaj are small by comparison to those in the literature. Hence, even if there were a bias of small farmers to misstate the size of their farms, given all are small farms, that bias would be similar for all, and thus could not explain differences in costs between small and large farms. In fact, given the tendency toward measurement error in farm size we use a proxy for farm size; the number of date palms. Date palms are the primary crop on falaj farms and given there is an optimal spacing of date palms, the number of trees should be proportional to farm size. This use of a proxy removes the possibility of bias in stating farm size.

A MODEL OF ECONOMIES OF SCALE FOR FALAJ FARMS

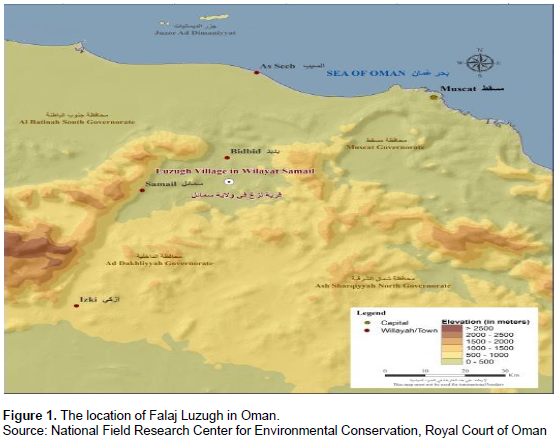

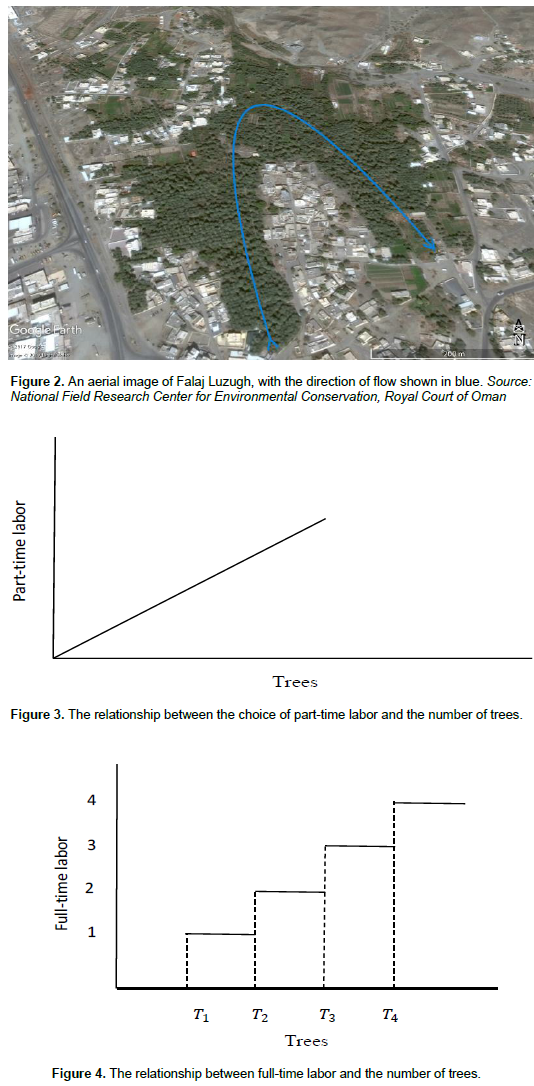

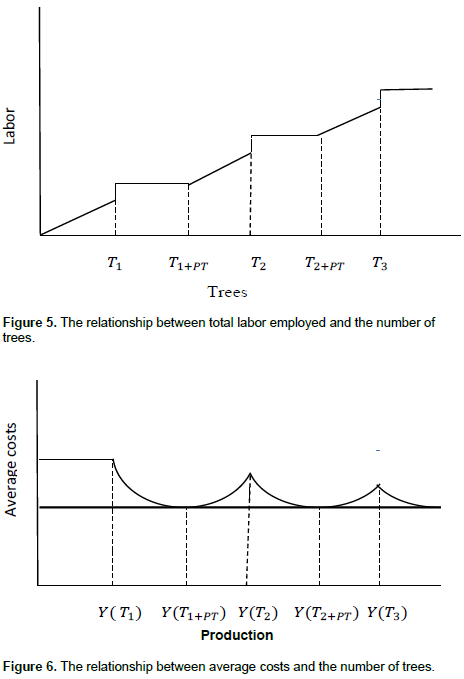

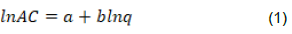

Given the aforementioned explanations driving the relationship between farm size and productivity are not relevant for a falaj, this begs the question as what might explain the differences in average costs between small and large falaj farms. It was argued that differences in average costs between farms of different sizes are owing to their use of part-time and full-time labor. It will be shown that the larger is the falaj farm, the greater the opportunity to avail of the less expensive full-time labor, and hence the lower average cost tends to be. A simplified version of a model that explains the relationship between part-time and full-time labor and average costs for different farm sizes was presented.

This pattern of U-shaped average cost curves repeats itself as the number of trees continues to increase. However, there are two characteristics of the average cost curve and it is important to note them. First, the local minima of the average cost are constant and thus represent the global minimum. This occurs at a level of trees such that full-time workers are used most efficiently. Second, the local maxima are falling. These local maxima occur where part-time labor is used to the greatest extent with full-time labor. As the number of trees increases, at these local maxima, the part-time labor represents a smaller portion of total labor, and thus the increase in average cost created by that part-time labor is less as compared to average cost at the previous local maxima. Both observations imply that though average costs are non-monotonic, there is a general tendency for average costs to decline as scale increases; the sense that the local maxima continually get smaller, and in the limit, approaches the global minimum.

Methods

One

falaj was studied to determine the extent to which small landholdings lead to an inability to realize economies of scale, thereby raising average costs and reducing profitability. This study was done as part of the Oman Earthwatch Programme (OEP) under the supervision of the National Field Research Center for Environmental Conservation. The OEP project, entitled “A study on the socio-economic and environmental sustainability of the Aflaj of Oman”, has as its stated primary objective to improve the socio-economic viability of the falaj by identifying alternative income sources or cost-reduction methods, which will increase falaj income. The present study reported in this paper is one aspect of this project that is concerned with understanding the costs faced by falaj farmers. For two reasons, the OEP project focused on only one falaj. First, field research on the aflaj is labor intensive, and thus expensive. Second, since the intention is to use the research to develop pilot projects, an intensive study of one falaj was necessary to more clearly identify the challenges faced by the falaj so as to design pilot projects that will have the highest chance of meaningfully impacting the falaj. The rest of this aspect of the study describes the site location, the survey used to collect the data, the measurement of the variables, and the specification of the regression model to be estimated.

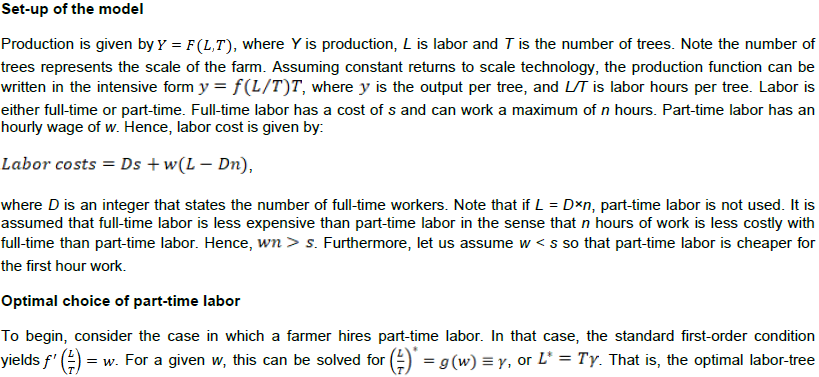

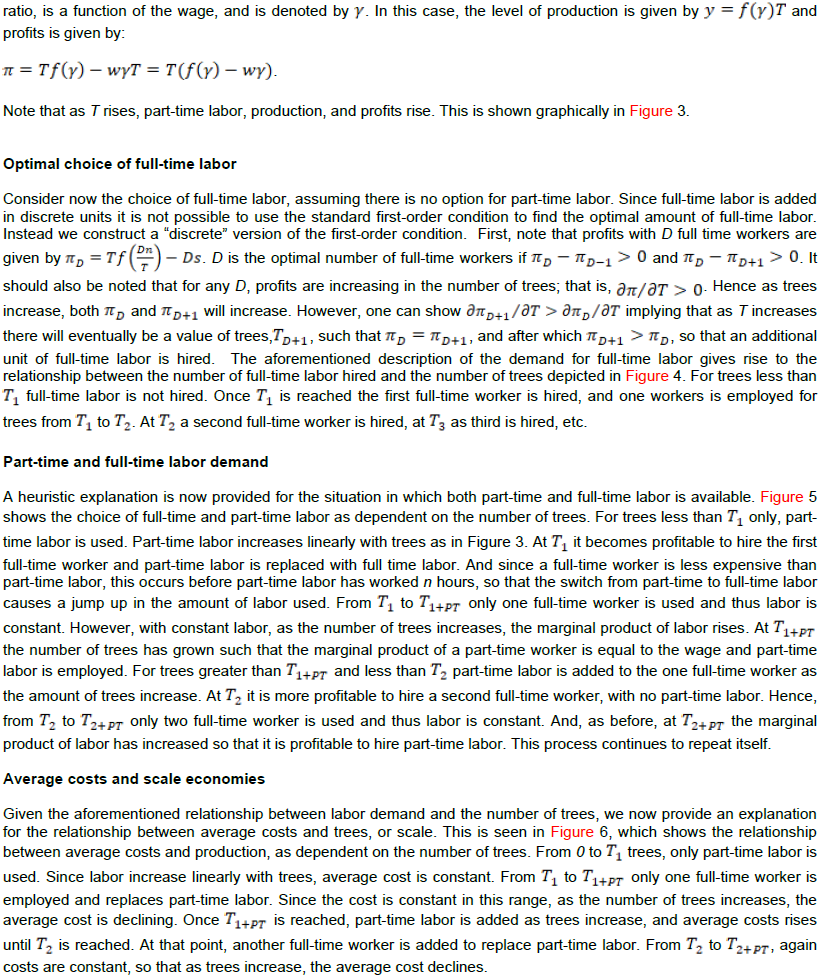

Site location

The falaj chosen for this study was Falaj Luzugh, in the Wilayat of Samail, Oman. Figure 1 shows the location of Luzugh in Oman, while Figure 2 shows an aerial image of the falaj with the direction of flow superimposed in blue. This falaj was chosen because it has exhibited a stable flow rate and thus any challenges faced are not caused by a reduction in the flow rate, but are likely due to the socio-economic problems discussed earlier, making it a good choice to better understand these challenges and develop appropriate pilot projects. Using survey results, economies of scale was examined in Falaj Luzugh. Given the argument that small farms result in higher costs, and thus, lower profits, since economies of scale cannot be realized, descriptive statistics are presented for both farm size in Falaj Luzugh and the profitability of those farms. Then economies of scale were test explicitly by estimating an average cost function for falaj farms.

The survey

The data in this report was collected from a survey of Falaj Luzugh completed in the summer of 2014 as part of the OEP project. Participants in the survey were identified as falaj water owners by manager of the falaj (called the wakil), who arranged for research assistants to visit the water owners in their homes to conduct the survey. As this was an extensive survey, the questions were asked verbally and the responses were recorded by the research assistants. Participation rate in the survey was high as forty six of the fifty identified water owners agreed to complete the survey.The survey contains two types of data. First, the survey asksquantitative questions regarding household size, cropping, sources of water, uses of water, size of harvests, prices received for their crops, the amount of the crop sold, the amount of the crop consumed at home, the inputs used in farm production, and the cost of those inputs. From this data, farm size, the size of the harvest, average costs, and farm profits were calculated. The second type of data is a qualitative data. The survey included a questionnaire that asked the farmers a range of question to elicit their perceptions regarding the economic relevance of the falaj profits and their willingness to adopt pilot projects to improve the economic performance of the falaj.

Measurement of variables

The measurement of the variables farm size, farm profits, costs, and production was described here.

Farm size

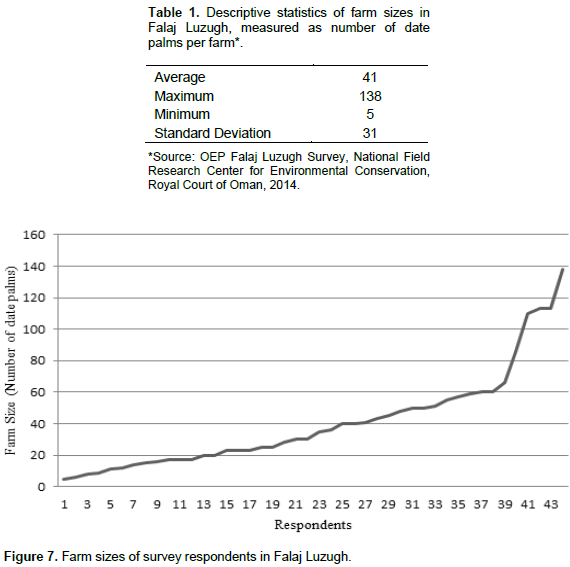

Average farm size in Falaj Luzugh is small. There are fifty identified shareholders of water but the land irrigated by the entire community is only 27.11 ha, implying the average land holding is 5,666 km2. While this indicates the land holdings are small, for the rest of this paper the measure of farm size used is the number of date palms. This is for three reasons. First, date palms are the primary crop. From an agronomic efficiency perspective, there is an optimal distance with which to space the date palms. Hence the number of date palms should be proportional to the size of the farm. Second, from a practical perspective, individual land holdings are irregularly shaped. The individual farmers would not be familiar with the number of square meters of land owned, and the field research needed to measure each farm would be excessively costly. Finally, as explained earlier, using date palms as a measure of size avoids the bias common in self-reported farm size.

Farm profits

Given it has been conjectured that farm profits are economically insignificant, we report on the magnitude of profits and their relative significance to household income. To determine the significance of farm level profits to the household, we use both qualitative and quantitative data. The qualitative portion of the survey asked two survey questions that elicit the participants’ perceptions regarding the significance of the income generated by their falaj farms. These questions, and a summary of the responses, will be discussed subsequently. The quantitative portion of the survey collected data on crops grown, the harvest of each crop, and the selling price of the crop, with which we were able to measure the total revenue for each farm, and thus profits after subtracting costs (subsequently described). However, in many cases, some crops were not sold, but rather consumed at home. In this case, average prices others sold the crop at were used to estimate the value of the crop. To determine the significance of farm level income it should be compared to household income. However, since we do not have data on household income, to determine their significance to households we express profits relative to average family income in Oman to estimate their significance. It should be noted that using the wholesale price to measure the value of home consumed crops underestimates their value. The fact that these were consumed at home implies the marginal value in consumption of the crop exceeded this wholesale price at which they could have been sold. While one may think to estimate the value of home consumption at the retail price, this would overestimate their value. The reason is a household may consume a crop at home even when its marginal value in consumption is below the retail price, as long as it exceeds the wholesale price. In fact, the only way to accurately measure the value of home consumed crops would be to have an estimate of the marginal value in consumption of the crop, which is to say an estimate of household demand for the crop, which is not available. And since this paper is concerned with the possible income generation of the falaj, we chose to estimate the value of the crops at their selling price, that is, the wholesale price.

Costs

Costs are measured both to compute profits, as well as to measure average costs to determine if economies of scale are present. Estimates of costs are taken from the estimates provided by individuals on the survey related to labor, fertilizer, seeds, water rented, and pollination of date palms. The primary cost identified is labor. The survey asked the number of part-time and full-time workers employed and, since the farmer may have the employee do other work not associated with the falaj, the farmer was asked to approximate the proportion of their time allocated to the falaj farm to determine the labor costs associated with falaj farms.

Production

The estimate of production is taken from the estimate of the harvest per tree, and for each variety of date palm. The market value of the harvest was then calculated using prices at which farmers could sell their dates. To convert the monetary amount of the harvest into kilograms of dates, the market value of the harvest was divided by the price of a particular variety; the Khalas dates. Hence, the number reported for the harvest is the “Khalas equivalent” kilograms of dates.

To test for economies of scale, an average cost function is estimated. Given the non-linear nature implied by economies of scale, a log-linear model is used. Specifically, the following equation is estimated:

where AC is average cost, q is the quantity produced, and a and b are parameters to be estimated, with the hypothesis that the constant a is positive and b is negative. The extent to which b is negative and statistically significant will indicate if economies of scale are present. However, as explained earlier, average costs are declining non-monotonically as average costs tend to rise when part-time labor is used. In particular, the higher is the proportion of part-time labor to total labor, the higher is average costs. We capture this with an interactive term in the slope parameter b. Specifically,

Here, the data on both farm size and profits are analyzed, and then proceeds by testing for the presence of economies of scale by estimating an average cost equation. It then considers the impact of economies of scale, and attitudes of farmers toward pilot projects to improve profitability of falaj farms.

Farm size in Falaj Luzugh

Economies of scale are less likely to be realized when farms are relatively small. This sub-section presents data on farm size in Falaj Luzugh. Using the number of date palms as a proxy for farm size as explained earlier, Figure 7 shows the size of farms of the survey respondents, while Table 1 reports the maximum, minimum, average, and standard deviation of farm size. The question of whether the sizes are too small to realize economies of scale must be determined from average cost data, however, the numbers do indicate significant dispersion in sizes of farms, implying it could be that while some farms are too small to experience economies of scale, others may be sufficiently large to realize economies of scale.

Profitability of farming in Falaj Luzugh

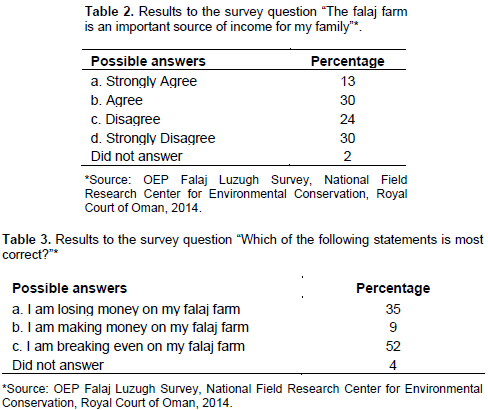

There exists significant dispersion in the size of farms. We first consider qualitative responses to questions asking about the significance of farming income. It should be noted that farming, for most, provides secondary income. Of the 46 respondents, only 4 did not report income from another source. Moreover, due to sensitivities in asking about individual income, a comparison of farming related income to other income could not be made. Instead the survey asked individuals two questions about the relative importance of farming income. The questions, with responses, are shown in Tables 2 and 3. Table 2 presents a summary of the responses to the statement “The falaj farm is an important source of income for my family”. While the question of whether the falaj farm is an important source of income is subjective, it does provide one with an understanding of the perception of the economic significance of the falaj to community members. While 54% either strongly disagreed or disagreed that the falaj farm provides a significant amount of income, it is clear that for a significant minority, 43%, the falaj still has economic significance. A similar conclusion can be reached by examining Table 3, which summarizes the responses to the question of whether the respondent viewed themselves as “making money, losing money, or breaking even” on their farm. Note that 35% report they are losing money on their falaj farm, similar to the 30% in Table 2 strongly disagreeing that the falaj farm provides significant income. In contrast, 9% report they are making money on their falaj farm, which is similar to the 13% strongly agreeing that the falaj provides significant income.

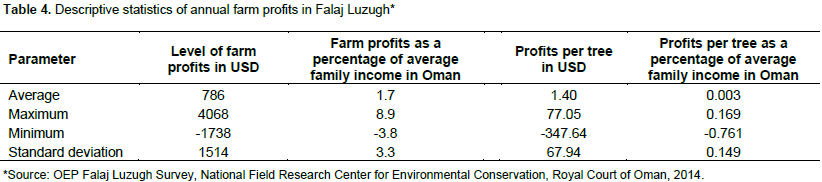

However, 52% report they are breaking even on their falaj farm. As this could include those who perceive themselves as making or losing an insignificant amount of money on the farm, this would appear to correspond to the combined 54% in Table 2 that either agreed or disagreed that their falaj farm provided significant income. In other words, an individual that felt they were approximately breaking even on their falaj farm may have agreed or disagreed with the statement that their farm provided significant income. In any case, it is clear that while few view themselves as making money on their farm, more than half of the respondents were not losing money. This suggests that while the falaj farms are not of great economic significance, there is still a possibility for the falaj to be economically relevant. Nevertheless, as indicated by Table 2, 54% disagreed with the statement that the falaj provided an importance source of income. Similarly, in Table 3, 35% said they were losing money on the falaj farm, and 52% said they were breaking even. Hence, most perceive the falaj farms as providing an insignificant level of income, with some reporting losses. Apart from the perceptions regarding income from farming, quantitative data on profits was collected, as explained later. The results of the survey are consistent with the perceptions of the farmers. The descriptive statistics regarding profits are reported in Table 4. Column two shows the absolute level of farm profits, while column three expresses this in percentage of average family income in Oman in 2013, which is $45,708. To express profits in per unit terms, column four reports profits per tree, while column five expresses profits per tree as a percentage of average family income.

The average profit per year is $786, corresponding to 1.7% of average family income. Though positive, it is low relative to average family income, consistent with the farmers’ perceptions that most are breaking even. There is also significant dispersion. The maximum profit recorded is 8.9% of average family income, consistent with some suggesting falaj farming is an important source of income. The minimum profit (maximum loss) is equivalent to 3.8% of average family income. Moreover, the standard deviation is $1,514, equivalent to 3.3%, of average family income, indicating that there are substantial differences in farmers’ profits from farming. Hence, as with farmer perceptions, the profits calculated suggests that while some are making significant income from farming, and some are losing money, the average person is making an insignificant amount of income from farming. While the absolute measure of profits can be used to illustrate the magnitude and dispersion in profits throughout the falaj, such dispersion could only be due to differences in farm size, or number of trees. Hence, columns four and five measure profits per tree. As with the absolute measure, there is dispersion in profits per tree, indicating that the variation in profits in the falaj is due to more than just variation in the number of trees owned.

Evidence of economies of scale in Falaj Luzugh

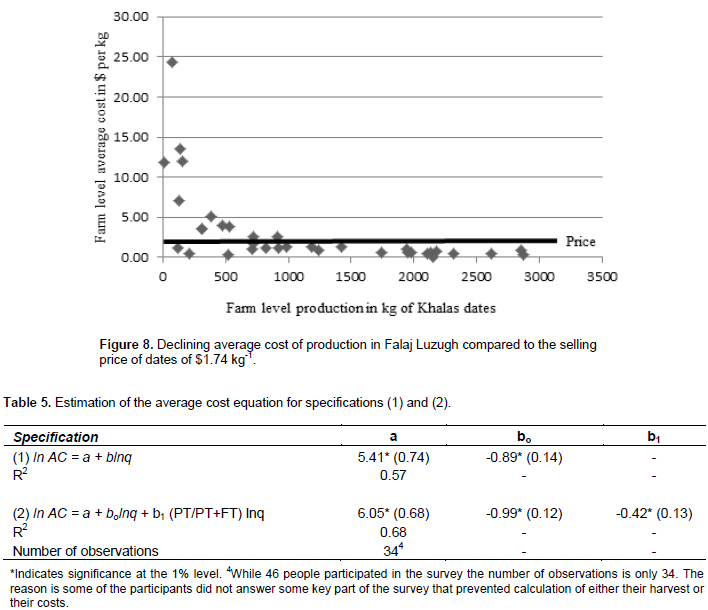

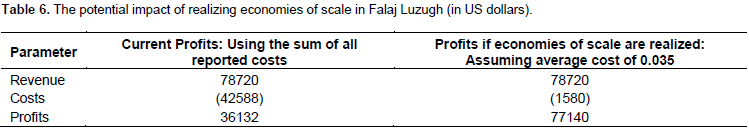

It was established that the average farm in Falaj Luzugh generates an insignificant level of income. Here, presents evidence that the explanation for the low income generation is due, at least in part, to high average costs associated with the inability to realize economies of scale. This is accomplished by testing for the relationship between average cost and production. Using the data collected from the survey on labor employed and its cost, it was calculated the number of full time workers employed on falaj farms is 21.15, with the average farmer employing 0.48 full time workers. While other costs are identified, the labor costs comprise 93% of costs, demonstrating that labor costs are a substantial portion of total costs. Average cost is calculated as total cost divided by production. Using farm level data on average cost and production described subsequently, Figure 8 graphs the production of each farm against each farm’s average cost. It is clear that the larger production, and thus larger farms, is associated with lower average costs. To provide context on the magnitude of average costs, Figure 8 also shows the selling price of Khalas dates ($1.74 kg-1). As one can see, lower amounts of production are associated with average costs that are higher than the price; implying profits per unit are negative for small farms. To further test for economies of scale, an average cost function is estimated using Equations 1 and 2. The estimation results of both specifications are presented in Table 5. In both specifications, the sign of the production coefficient is negative and significant at 1% level, indicating evidence of economies of scale. In specification 2, the sign of is also negative, and statistically significant, and is thus inconsistent with the theory presented. However, only four farmers reported the use of part-time labor, which may not be a sufficient number to test this aspect of the theory. In either case, the results indicate evidence of economies of scale, and given production is directly related to the size of farms this implies small farmers will face higher average costs, and thus lower profits per unit produced.

Impact of economies of scale on the economic viability of the Falaj

The small holdings that characterize the falaj imply economies of scale are not being realized by many farmers, and thus profits are lower than otherwise. To better understand the extent to which the small holding reduce profits in the falaj, we compare the current average costs and profits of all falaj farms to the average costs and profits if the falaj is operated as a single farm. If the falaj is operated as a single farm then economies of scale would be realized and average costs would be reduced. The reduced average cost can be approximated using the estimated average cost equation. Using the sum of all farm’s production as the falaj production, the falaj level production would be 45156 kg. Substituting this number into the estimated average cost equation from specification 1, the average cost would be $0.035kg-1.To put this into perspective, the minimum average cost reported is $0.263 kg-1. One can then extrapolate to total costs. Summing all reported costs of all farms, the total cost of all falaj production was $42588. However, if the average cost of $0.035 kg-1 is used, the total cost of all falaj production would be $1580.46. And while there is no guarantee that the equation holds outside the estimated range of data, there would clearly be a substantial reduction in cost. Indeed, even if one uses the minimum average cost reported of $0.263 kg-1 as the estimate of average cost for the entire falaj, the total cost of all production would be $11876.03, still far below the actual cost reported. Table 6 shows the revenue, costs, and profits of the falaj reported on the survey, and under the assumption that economies of scale are realized by having the falaj operate as a single farm. The data indicates there would be a substantial reduction in average costs, and a corresponding increase in profits, were the falaj to function as a single farm. This illustrates the impact that the small holdings, and the implied inability to realize economies of scale, have on the economic performance of falaj farms, and the economic viability and sustainability of the falaj community.

As the study was conducted to determine potential pilot projects to improve the economic sustainability of the falaj, the survey asked farmers a series of questions about their willingness to participate in pilot projects and the heritage value of the falaj. This is particularly relevant when one considers the significance of the aflaj to Oman’s culture and heritage. If a pilot project is viewed as undermining the heritage value of the falaj, then that project is unlikely to have community support. Regarding the existence of heritage value, the farmers were asked to respond to the statement “The falaj is an important source of my heritage”, 96% strongly agreed, indicating there is heritage value to falaj farmers. Given some potential pilot projects may involve changes in the falaj, the survey asked about their willingness to adopt such changes. To measure the extent to which one values this heritage the participants were asked to respond to the following two statements: “For a high enough price I would consider selling my falaj water”, and “For a high enough price I would consider selling my falaj land”. In both cases, 74% strongly disagreed with the statements, and 13% disagreed. This suggests that since farmers value the heritage represented by falaj farms they are unwilling to divest in their land and water.

This study have shown that the small land holdings characterizing the falaj communities in Oman prevent economies of scale from being realized, thereby threatening the economic viability and sustainability of these indigenous community based water management systems. Apart from the economic viability of the falaj as an income generating activity, the small holdings and the poor economic performance created also may impact the ability of the falaj to maintain the existing physical structure of the falaj. As described in earlier, the falaj raises revenue by auctioning of water. Given the low profits generated by the small farms in the falaj, the value of water to farmers will be relatively small, and thus the willingness to pay for auctioned water will be low. Hence, the revenue raised by the falaj may be insufficient to fund maintenance. The finding of the presence of economies of scale is in contrast to much of the literature, which has found an inverse relationship between farm size and productivity, and thus no evidence for economies of scale. The reason for this difference in findings is the characteristics driving the aforementioned inverse relationship, such as labor market imperfections, measurement error, and land quality differences, are unlikely to be present for falaj farms, for reasons explained earlier. Rather the finding of the presence of economies of scale rests on an effect that has not been studied in the literature; namely, that the small farms that characterize the falaj have higher labor costs, as they must rely on the more expensive part-time labor, than full time labor. While our finding is in contrast to much of the literature, it is consistent with the finding of Savastano and Scandizzo (2017) that for very small farms, such as those that would characterize the falaj, there is a direct relationship between farm size and productivity.

To highlight the significance of the estimated economies of scale, it was demonstrated that in the falaj under study, if the falaj operated as a single farm, the profits derived from farming would be approximately twice as much. While the purpose of this calculation was only to illustrate the extra cost being created by small holdings, it is also suggestive of a potential means to realize economies of scale; namely, to operate the falaj as a single farm. Indeed, given the low profits of falaj farms and the existence of economies of scale, there are incentives for large farms to buy small farms, as the land is more valuable when consolidated. If this occurred, then over time farms would grow in size, as would farm profits. Hence, the presence of economies of scale begs the question as to why small farms persist in the falaj. One explanation is that farmers value their falaj farm not only for its income generating potential, but also for its “heritage” value. As explained earier, 96% of the farmers strongly agreed that the falaj is an importance source of heritage, and 87% they would not consider selling their land or water. This suggests they are unwilling to divest in their land and water due to its heritage value. Another mechanism to realize economics of scale would be to operate the falaj land as a cooperative farm. However, whether or not a cooperative would be supported is not clear. Since the falaj is itself a cooperative method of managing water, the social institutions for cooperation are already in place.

Nevertheless, the private property of rights of the water and land are part of those social institutions, and thus it is not clear whether individuals would interpret a cooperative as divesting in land or water. If it is viewed as divestment, there may be a lack of support for the cooperative. While this paper has concentrated on economies of scale in production, it is not clear whether the improvement in falaj farm profits owing to the cost reduction that comes from realizing such economies of scale would be sufficient to provide for falaj maintenance, attract the young to the falaj, and ensure the economic sustainability of the aflaj. It may also be necessary to increase falaj farm related revenue, such as by changing to higher value crops. However, the small farms that characterize the aflaj tend to face significant economies of scale in other respects, such as marketing and distribution of crops (Poulton et al., 2010). For this reason, collective action, such as cooperatives, may have a role to play in improving the profitability of small farms (Verhofstadt and Maertens, 2014;

Tolno et al., 2015; Orsi et al., 2017; Corsi et al., 2017).

This paper has demonstrated that for the small farms characterizing Oman’s aflaj economies of scale are present in production, which results in lower profitability. Thus realizing scale economies would increase profitability. Moreover, as discussed, other means to increase profits (such as marketing of higher value crops) may also exhibit economies of scale. Hence, collective action to realize economies of scale is important to the economic sustainability of the aflaj. However, give the reluctance of the local population to divest in land or water due to the heritage value of the falaj, and given that collective action could be interpreted as divestment, it is not clear that such collective action would be supported. Therefore, future research should focus on identification of other means to increase the profitability of falaj farms and the extent to which the small falaj farms face economies of scale in adopting these other means. Moreover, given the presence of economies of scale, future research should determine whether collective action is required to realize scale economies and increase the profitability of the falaj farms, and whether such collective action would be supported by the community.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

This work was supported by the National Field Research Centre for Environmental Conservation and Earthwatch Institute teams working in the Sultanate of Oman for the Diwan of Royal Court as part of the Oman Earthwatch Program 2009 to 2015. The authors would like to thank Mr. Ishaq Al Shabibi for his able research assistance.

REFERENCES

|

Aflaj Inventory Project Summary Report (2001). Ministry of Regional Municipalities and Water Resources, Oman.

|

|

|

|

Al Ghafri AS (2004). Study on Water Distribution Management of Aflaj Irrigation Systems of Oman. Ph.D. Thesis, Hokkaido University, Japan.

|

|

|

|

|

Al Hatmi H, Al Amri S (2001). Aflaj maintenance in the Sultanate of Oman. Proceedings of the First International Conference on Qanats, Ministry of Energy 4:154-161.

|

|

|

|

|

Al Marshudi AS (2007). The falaj irrigation system and water allocation in Northern Oman. Agric. Water Manage. 91:71-77.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ali DA, Deininger K (2015). Is There a Farm Size–Productivity Relationship in African Agriculture? Evidence from Rwanda? Land Econ. 91(2):317-343.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Barrett CB, Bellemare MF, Hou JY (2010). Reconsidering conventional explanations of the inverse productivity–size relationship. World Dev. 38(1):88-97.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bhalla SS, Roy P (1988). Misspecification in farm productivity analysis: The role of land quality. Oxford Econ. Pap. 40:55-73.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bosi L (2009). Social-ecological change and adaptation in a traditional irrigation system: The case of Falaj Hassas (Oman). M.S. Thesis No. 531008. University of Oxford.

|

|

|

|

|

Carletto C, Savastano S, Zezza A (2013). Fact or artifact: The impact of measurement errors on the farm size-productivity relationship. J. Dev. Econ. 103:254-261.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Corsi S, Marchisio LV, Orsi L (2017). Connecting smallholder farmers to local markets: Drivers of collective action, land tenure and food security in east Chad. Land Use Policy 68:39-47.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Desiere S, Jolliffe D (2018). Land productivity and plot size: Is measurement error driving the inverse relationship? J. Dev. Econ. 130:84-98.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Dutton R (1995).Towards a secure future for the aflaj in Oman. Proceedings of the International Conference on Water Resources Management in Arid Countries, 12-16 March, Muscat, Oman.

|

|

|

|

|

Eswaran M, Kotwal A (1986). Access to capital and agrarian production organization. Econ. J. 96:482-98.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gourlay S, Kilic T, Lobell D (2017). Could the Debate Be Over? Errors in Farmer-Reported Production and Their Implications for the Inverse Scale-Productivity Relationship in Uganda. World Bank. WPS8192.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Heltberg R (1998). Rural market imperfections and the farm size-productivity relationship: Evidence from Pakistan. World Dev. 26:1807-1826.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Henderson H (2015). Considering technical and allocative efficiency in the inverse farm size-productivity relationship. J. Agric. Econ. 66:442-469.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Holden S, Fisher M (2013). Can area measurement error explain the inverse farm size productivity relationship. Center for Land Tenure Studies, Norwegian University of Life Sciences. Available at https://ideas.repec.org/p/hhs/nlsclt/2013_012.html.

|

|

|

|

|

Kagin J, Taylor JE, Yunez-Naude A (2016). Inverse Productivity or Inverse Efficiency? Evidence from Mexico. J. Dev. Stud. 52(3):396-411.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lamb RL (2003). Inverse productivity: land quality, labor markets, and measurement errors. J. Dev. Econ. 71:71-95.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Limbert M (2001). The senses of water in an Omani Town. Soc. Text 19:35-55.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

McCann I, Al Ghafri A, Al Lawati I, Shayya W (2002). Aflaj: The challenge of preserving the past and adapting to the future. Proceedings of Oman International Conference on the Development and Management of Water Conveyance Systems, May 18-20. Muscat, Oman.

|

|

|

|

|

Nash H, Agius DA (2011). The use of stars in agriculture in Oman. J. Semitic Stud. 56:167-182.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Nkonde C, Jayne TS, Place F, Richardson R (2015). Testing the farm size-productivity relationship over a wide range of farm sizes; Should the relationship be a decisive factor in guiding agricultural and development and land policies in Zambia. World Bank Conference on Land Poverty. March 23-27, Washington, D.C.

|

|

|

|

|

Orchard J, Gordon S (1994). Third millennium oasis towns and environmental constraints on settlement in the Al Hajar region. Iraq 56:63-100. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/iraq

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Orsi L, De Noni I, Corsi S, Marchisio LV (2017). The role of collective action in leveraging farmers' performances: Lessons from sesame seed farmers' collaboration in eastern Chad. J. Rural Stud. 51:93-104.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Poulton C, Dorward A, Kydd J (2010). The future of small farms: New directions for services, institutions, and intermediation. World Dev. 38(10):1413-1428.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Savastano S, Scandizzo P (2017). Farm size and productivity: A direct-inverse-direct relationship. World Bank. WPS8127.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sen AK (1962). An Aspect of Indian Agriculture. The Economic Weekly. 14:243-246.

|

|

|

|

|

Sutton S (1984). The falaj – a traditional cooperative system of water management. Waterlines 2:8-12.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Tolno E, Kobayashi H, Ichizen M, Esham M, Balde BS (2015). Economic analysis of the role of farmer organizations in enhancing smallholder potato farmers' income in middle Guinea. J. Agric. Sci. 7 (3):123-137.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Toufique KA (2005). Farm Size and Productivity in Bangladesh Agriculture: Role of Transaction Costs in Rural Labour Markets. Econ. Political Weekly. 5:988-992.

|

|

|

|

|

Verhofstadt E, Maertens M (2014). Smallholder cooperatives and agricultural performance in Rwanda: Do organizational differences matter? Agric. Econ. 45(51):39-52.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Wilkinson J (1977). Water and Tribal Settlement in South-East Arabia: A Study of the Aflaj of Oman. Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK.

|

|

|

|

|

Zekri S, Kotagama H, Boughanmi H (2006). Temporary water markets in Oman. Agric. Marine Sci. 11:77-84.

Crossref

|

|